T. D. Alexander

In most English Bibles, the books of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs come between the historical and prophetic books. These five books differ noticeably in content and style from all the other books of the OT as well as from one another. They are the principal representatives in the OT of what is now known as wisdom and lyrical literature. “Wisdom” applies to Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes, and “lyrical” relates to Psalms and Song of Songs. Since the two classifications are distinctive, we will consider them separately; however, it is important to note that a few psalms are sometimes associated with wisdom literature (e.g., Ps 49).

Wisdom Books

The books of Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes are often grouped together under the heading of wisdom literature. The book of Job is mostly a dialogue that centers on a righteous man, Job, who experiences a series of personal disasters, including the death of his children. Although Job protests his innocence, his friends encourage him to repent, convinced that he must have sinned greatly in order to suffer so much. Proverbs, as its name suggests, is largely an anthology, or collection, of short proverbial sayings that often contrast two actions, one good and one bad. Ecclesiastes is a monologue addressing the absurdity or meaninglessness of life. The author, who presents himself as a king of Jerusalem, explores various avenues to discover what gives purpose to living.

While the books of Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes differ enormously in form and content (see Introductions to each book), they also have much in common, and there is considerable value in looking at them together. They complement each other by providing a more rounded perspective on some of life’s big issues. Whereas the book of Proverbs commends righteous living in order to enjoy God’s favor, the book of Job explores the case of someone who is exceptionally righteous but suffers greatly. Whereas Proverbs conveys the idea that God blesses those whose lives are marked by integrity rather than by falsehood, Ecclesiastes highlights the disillusionment we feel when we observe the lack of moral order in the world; since the wicked appear to prosper and the righteous seem to suffer, what advantage does a righteous person have over the wicked? Whereas the book of Proverbs seeks to inculcate consistent, righteous behavior, the books of Job and Ecclesiastes look to avoid a simplistic interpretation of recurrent patterns of life.

The Distinctive Nature of Wisdom Literature

Wisdom literature is generally considered a distinctive category within the literature of the OT. Although the precise characteristics of wisdom literature are subject to debate, five features are usually present.

1. Wisdom literature uniquely emphasizes the importance of human reason and understanding. Wisdom literature contrasts with the historical books and the prophetic books. On the one hand, the historical books recount a unique story of God’s dealings with the people of Israel. This grand narrative defines who the people are and enables them to understand their place in the world. On the other hand, the prophetic books record divine messages containing both threats and warnings that challenge the people to obey God. The wisdom books are neither a grand story nor divine messages. They are quite different in that they call on people to think hard about life and how they should live.

While the wisdom books do not claim to originate directly from God, unlike OT laws (such as those God gave through Moses on Mount Sinai) and divine messages of encouragement or rebuke (such as those God gave through visions to prophets), they nevertheless claim authority for what they have to say. Their advice comes in part from observing the behavior of people and thinking about creation. For example:

I went past the field of a sluggard,

past the vineyard of someone who has no sense;

thorns had come up everywhere,

the ground was covered with weeds,

and the stone wall was in ruins.

I applied my heart to what I observed

and learned a lesson from what I saw:

A little sleep, a little slumber,

a little folding of the hands to rest—

and poverty will come on you like a thief

and scarcity like an armed man. (Prov 24:30–34)

Here knowledge comes through observation and reflection. This kind of understanding does not depend upon divinely given laws or prophetic visions.

2. Wisdom originates with God. The wisdom books view creation and life through the lens of belief in the God of Israel. We cannot find wisdom apart from him because “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov 9:10; cf. Job 28:28; Prov 1:7; 16:6; 31:30; Eccl 5:7; 12:13). The books encourage us to use our minds and think independently within the context of trusting God:

Trust in the LORD with all your heart

and lean not on your own understanding;

in all your ways submit to him,

and he will make your paths straight.

Do not be wise in your own eyes;

fear the LORD and shun evil. (Prov 3:5–7)

Wisdom literature encourages us to think diligently but humbly.

Basic to wisdom literature is the belief that God has created a coherent and meaningful universe:

By wisdom the LORD laid the earth’s foundations,

by understanding he set the heavens in place. (Prov 3:19)

How many are your works, LORD!

In wisdom you made them all;

the earth is full of your creatures. (Ps 104:24)

Based on the assumption that God designed everything in the universe, the ancient Israelites believed that “truth,” in all its aspects, began and ended with God. For this reason the pursuit of “truth” brought one closer to God.

Such reasoning, however, is at odds with the beliefs of many twenty-first-century postmodern ideas. For many postmodern thinkers, it is folly to seek a rational explanation to life. There is no such thing as absolute truth, for everything is relative. Reason cannot bring us to “truth,” for “truth” does not exist. From this postmodern perspective, life is meaningless not because we have yet to discover the meaning but because there is no meaning to discover. For many postmodern people, the idea that God created a meaningful universe is folly. There can be no ultimate meaning to life, for there is no God.

The wisdom writings of the OT, however, start from a very different premise, one that is alien to many people today. The authors of these books believed that God created a meaningful universe. This does not imply that they did not struggle to make sense of life in the world. On the contrary, they struggled a great deal. But through their struggle they realized that they could discover meaningful existence only by taking God into account. Wisdom itself comes through revelation. For this reason, the authors of Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes unanimously affirm that “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov 9:10; cf. Job 28:28; Eccl 12:13).

3. Wisdom embraces all areas of life. Since all knowledge comes from God, there was in ancient Israel no distinction between religious and secular truth. This was so because the Israelites viewed God as creator and sustainer of all life. Furthermore, they linked wisdom with creation itself. To underline this connection, Prov 8 personifies wisdom: wisdom speaks. Wisdom was the first of God’s creations (Prov 8:22–31), and she describes how she was with God and assisted him in creating the world. This has important ramifications, because it gives wisdom a unique status. By implication, if creation depends upon wisdom, then to live wisely is to live in harmony with creation. To do otherwise is to oppose God’s purpose for the world.

This link between wisdom and creation undergirds the whole book of Proverbs. To live wisely is about participating positively in God’s creation-purposes. It is about building a society that is in harmony with God’s purposes. Aptly, the words “wisdom,” “knowledge,” and “understanding” together describe the creation of the cosmos, the construction of the tabernacle and temple, and the building of the family home:

By wisdom the LORD laid the earth’s foundations,

by understanding he set the heavens in place;

by his knowledge the watery depths were divided,

and the clouds let drop the dew. (Prov 3:19–20, emphasis added)

The same three terms describe Bezalel and Huram, who had special responsibilities for overseeing the construction of the tabernacle and Jerusalem temple, respectively (Exod 31:3; 35:30–31; 1 Kgs 7:13–14). They construct God’s earthly dwelling place with the same qualities that God used to construct the world. This parallel is all the more interesting because ancient Israelites viewed the tabernacle and temple as models of the cosmos. Extending this idea one stage further:

By wisdom a house is built,

and through understanding it is established;

through knowledge its rooms are filled

with rare and beautiful treasures. (Prov 24:3–4, emphasis added)

By emphasizing the role of wisdom, understanding, and knowledge in creating a family home, a significant link is made with the construction of God’s dwelling place. These parallels between the cosmos, the tabernacle/temple, and the ordinary home are no coincidence, for they reflect the overall purpose of God that he should dwell on the earth, cohabiting it with humans (see “Temple”). For people to participate in God’s creation-purpose, it is essential for them to have wisdom, knowledge, and understanding. These attributes, however, are not innate. They come from God:

For the LORD gives wisdom;

from his mouth come knowledge and understanding. (Prov 2:6, emphasis added)

4. Wisdom and ethics. Wisdom is about much more than acquiring factual knowledge and understanding. Wisdom is not equated simply with intellectual ability. Rather, it is about “doing what is right and just and fair” (Prov 1:3).

5. Wisdom and creation. Unfortunately, all on earth is not as it should be, for people are drawn to folly rather than wisdom. With good reason, the father in Prov 1–9 appeals to his son to choose wisdom rather than folly. Whereas wisdom offers life, folly brings death. To highlight these contrasting ways of living, the father personifies wisdom and folly as two women. Folly is cast as a seductive adulteress who lures unsuspecting young men into her house with the promise of sexual gratification. But as the father points out, the punishment for adultery is death (Prov 7:21–27; 9:18). Wisdom also invites young men into her house, but here there is no threat of death, only life (Prov 8:35; 9:11).

Lyrical Books

The two main books of lyrical literature are Psalms and the Song of Songs. Although both books are poetry, they are very different. While the Psalter (i.e., the book of Psalms) is a collection of 150 songs devoted to the worship of God, the Song of Songs comprises a series of interconnected stanzas that express the passionate feelings of two lovers for one another. Whereas the songs within the Psalter address a wide variety of human situations, the Song of Songs narrowly focuses on one important theme. Whereas the Psalter abounds in references to God, constantly putting him at the very center, the lovers in the Song of Songs have eyes only for each other; in fact, throughout the whole book God’s name never appears (or appears once in 8:6, if we include the NIV text note). While the Psalter is an obvious candidate for inclusion within the canon of the OT, the Song of Songs initially appears somewhat out of place. Nevertheless, both books contribute in different ways to a deeper theological reading of the OT (see Introductions to both books).

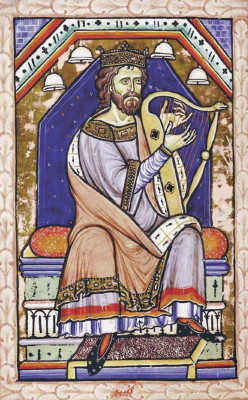

The Psalter comprises material that ancient Israel widely used in public worship over a long period of time. The psalms, however, come from different periods of time. Some of the psalms are much older than others, with many going back to the time of King David. The present collection of 150 psalms has been created by combining shorter collections of psalms that already existed. Some of these collections probably circulated for centuries before being combined to produce the Psalter as we now know it. The final collection undoubtedly came into existence in the postexilic period, suggesting that the Psalter may well have been produced to be the hymnbook of the Jews who returned from exile to rebuild the city of Jerusalem.

As might be expected, the 150 songs within the Psalter cover a wide range of themes. In doing so, the psalms articulate a host of human emotions, from exalted praise and adoration of God to utter despondency in the face of extreme difficulties. The psalms move from distraught pleas for help to exuberant words of gratitude for God’s compassion and help. The psalms acknowledge that life can be harsh and uncompromising. Nevertheless, in spite of everything negative that an individual or community may experience, there is a sovereign God who is compassionate and merciful. While the Psalter does not neglect the darker side of life, there is within it an overall movement from lament to praise.

In marked contrast to the book of Psalms, the Song of Songs centers on one theme: romantic love. From beginning to end, the entire book explores, often in vivid detail, the mutual delight that a man and woman may share. The language frequently overflows with graphic imagery as the lovers express their yearning for one another. She ardently says,

Like an apple tree among the trees of the forest

is my beloved among the young men.

I delight to sit in his shade,

and his fruit is sweet to my taste.

Let him lead me to the banquet hall,

and let his banner over me be love.

Strengthen me with raisins,

refresh me with apples,

for I am faint with love.

His left arm is under my head,

and his right arm embraces me. (Song 2:3–6)

His response is equally evocative:

Your teeth are like a flock of sheep just shorn,

coming up from the washing.

Each has its twin;

not one of them is alone.

Your lips are like a scarlet ribbon;

your mouth is lovely.

Your temples behind your veil

are like the halves of a pomegranate.

Your neck is like the tower of David,

built with courses of stone;

on it hang a thousand shields,

all of them shields of warriors. (Song 4:2–4)

Through nature-rich metaphors the couple share their ardent passion for each other.

Set side by side, the Psalter and the Song of Songs are vivid reminders of the significance of relationships for human existence. The Psalter emphasizes at length the importance of the divine-human relationship, recognizing that this is frequently a relationship that is, from a human perspective, difficult to sustain. By way of encouragement, the intimacy of human love illustrates indirectly something of the passion of God’s love for people. The one who designed male and female for intimate union, intending that they should become one flesh, is the very one who desires to live in close and harmonious relationship with them. Human love is to be an illustration of divine love. For this reason, the apostle Paul instructs husbands to love their wives, “just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Eph 5:25). In the same vein, the book of Revelation describes “the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, . . . as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband” (Rev 21:2). While the Song of Songs may not address explicitly the divine-human relationship, it uniquely contributes to the canon of Scripture.

Unity and Diversity

In unexpected ways the lyrical and wisdom books add to the theological richness of the OT canon by complementing the historical and prophetic books that surround them. Whereas the historical books describe selected actions of God at particular times and places, the wisdom books highlight the difficulty of comprehending God’s role in everyday occurrences. Whereas the prophetic books communicate messages of warning and hope to people from God, the book of Psalms consists of messages that people prayed in private or sung in public to God. By reflecting on the complementary nature of these books, we may appreciate something of the rich diversity that exists within the Bible.

Unfortunately, some scholars exploit this instructive diversity by arguing that it arises out of differing and sometimes contradictory views of God. Diversity, however, is not incompatible with unity. As the human body ably illustrates, eyes and ears have little in common, yet both are vital components within a single entity. In the same way, the wisdom and lyrical books expand the variety of literary forms that comprise the Bible and significantly contribute to its theology.

While the wisdom and lyrical books are very different from one another as works of literature, they are all linked, apart from the book of Job, in some way to the Davidic monarchy: Many of the psalms are attributed to David. The book of Proverbs consists largely of collections of proverbial sayings associated with David’s son Solomon. The author of Ecclesiastes introduces himself as a “son of David, king in Jerusalem” (Eccl 1:1), and the Song of Songs begins with a reference to Solomon (Song 1:1). (For the implications of these observations for authorship, see Introductions to each book.) These links to the Davidic dynasty add substantial weight to the OT expectation that the royal line of David will play a special role in the fulfillment of God’s redemptive purposes. Eventually these expectations come to fulfillment in Jesus Christ, the “son of David” (Matt 1:1) and the one “greater than Solomon” (Luke 11:31). In him we see a life that reflects all that the wisdom and lyrical books have to teach.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()