Annotations for Job

1:1—2:13 The Prologue. This prose account of Job’s tragic life is composed of seven scenes: (1) Job’s devotion to God (1:1–3); (2) Job’s devotion to his family (1:4–5); (3) the first test of Job proposed (1:6–12); (4) the first test executed, and Job’s response (1:13–22); (5) the second test of Job proposed (2:1–6); (6) the second test executed and Job’s response (2:7–10); (7) introduction of Job’s friends (2:11–13).

1:1–5 The Main Character Introduced. This brief introduction describes Job in terms of his geographic location, his devotion to God and family, and his wealth.

1:1 land of Uz. Perhaps two locations are possible: (1) Edom (Jer 25:20–21; Lam 4:21) seems preferable, or (2) in the north in Hauran (see Gen 10:23). Job. Cognates of the name Job appear in literature of the patriarchal period, which suggests we may believe Job was a real person, not merely a literary invention. Job, Noah, and Daniel are said to constitute the three most righteous men of all time (Ezek 14:14, 20). Two pairs of virtues describe Job’s religious devotion: (1) blameless and upright. Having personal integrity and acting justly; this does not means Job was sinless, for he admits he has sinned (7:21). (2) feared God and shunned evil. Having a genuine devotion toward God and avoiding evil deeds (28:28), virtues that characterize the wise individual in wisdom literature (Prov 1:7; 9:10).

![]()

![]()

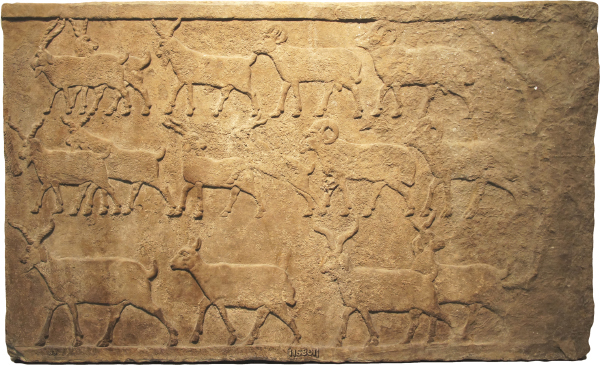

1:2–3 Describes Job’s family, livestock, and servants for two reasons: (1) to enhance the portrait of Job’s greatness and (2) to prepare the reader for the upcoming tragedy that will destroy both Job’s family and cattle. In patriarchal times people measured wealth in terms of livestock (Gen 30:43).

1:2 seven sons and three daughters. The numbers seven and three indicate the completeness of Job’s blessing of children.

1:3 five hundred yoke of oxen. Equals 1,000 oxen since a “yoke” of oxen is two oxen, suggesting Job was involved in agriculture. people of the East. People east of the Jordan.

![]()

![]()

1:5 he would sacrifice. As spiritual leader of his family, Job acted in a priestly role (also a patriarchal practice, Gen 15:9–10) by offering “a burnt offering for each of them” after their festive occasions. These were “whole burnt offerings” (Deut 33:10), which were totally consumed by fire (see Lev 1 and note on Lev 1:9) and atoned for sin in general (see note on Lev 1:3–17), whereas sin offerings (see Lev 4 and note on Lev 4:1—5:13) atoned for individual sins. cursed God. Lit. “blessed God,” a euphemism, since to have the words “cursed” and “God” in the same sentence seemed inappropriate (cf. v. 11; 2:5, 9; 1 Kgs 21:10, 13).

1:6–22 Job’s First Test Executed and Job’s Response. The Lord himself initiates the first test to show that Job serves God with no ulterior motive (v. 9). After Job loses everything of value in four successive tragedies on a single day, he blesses God for his sovereign care, not even mentioning his own losses (v. 21).

1:6 angels. See NIV text note. They came before the Lord to give an account of their activities. the LORD. The covenant name for God (Yahweh = LORD); occurs in the prologue and epilogue but not in the dialogue. Satan also came with them. Sets “Satan” (meaning “the adversary” or “the accuser”) off from the others. In Hebrew the definite article is used (“the satan”), suggesting that it is a title rather than a personal name (see Zech 3:1 and note). In 1 Chr 21:1 the article is not used since “Satan” had become a proper name for the adversary by that time. going back and forth on it. After the Lord initiates the conversation, Satan reports that he has been searching the earth to see if there is anyone who fears God “for nothing” (v. 9), i.e., with no ulterior motive.

1:8 There is no one on earth like him. The Lord presents Job as the exemplar of righteousness. This corroborates the portrait of Job in vv. 1–3, this time in the Lord’s own words, using the same two pairs of virtues (see v. 1 and note). See also 28:28.

1:9 Satan’s thorough search has not missed Job, the one challenge to Satan’s assumption that no one serves God without selfish motives.

1:10 hedge. Implies a hedge of thorns to keep marauders away; Satan has observed God’s protection of Job and his household.

1:11 Satan (v. 6) assumes that if God takes away Job’s family and property, Job will “curse” (lit. “bless”; see note on v. 5) God. That Satan had to request permission to harm Job is testimony to God’s sovereign rule of the world—here Job’s personal world, elsewhere in Scripture the universe God created (Ps 2; Phil 2:9–11; Heb 1:3–4).

1:12 on the man himself. The protective “hedge” (see v. 10 and note) is removed except for Job’s person.

1:13–22 Each disaster is reported by a “messenger” (v. 14), who is the only one to escape. The overlapping literary effect of the messages intensifies the emotional effect: “While he was still speaking, [yet] another messenger came” (vv. 16, 17, 18). Job himself receives the messenger. In keeping with the divine directive of v. 12, in this first test Job loses his livestock and servants (vv. 13–15), sheep and servants (v. 16), camels and servants (v. 17), and children (v. 18–19).

1:13 Probably a birthday celebration (see v. 4), interrupted by the bad news, making it all the more painful.

1:15 Sabeans. A distant tribe (Jer 6:20) from Sheba, probably located in present-day Yemen (see note on 1 Kgs 10:1). In the patriarchal era (the story’s time frame), they might still have been a roaming tribe.

1:16 fire of God. Lightning.

1:17 Chaldeans. Early tribal marauders (like the Sabeans; v. 15). Later they took control of Babylon and built a powerful empire that eventually destroyed Judah in 586 BC.

1:19 mighty wind. More than the east wind from the desert; a violent storm.

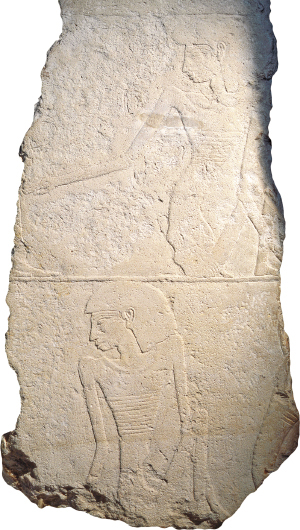

1:20 tore his robe and shaved his head. Signs of mourning (Isa 22:12; Jer 7:29). fell to the ground in worship. Prostrated himself, signifying humility in God’s presence.

1:21 Job’s two aphorisms acknowledge that (1) Job had nothing when he came into the world and will take nothing out of it, and (2) God is the source of all his possessions. Job acknowledges God’s sovereign hand even in times of calamity.

1:22 Confirms the Lord’s assessment of Job’s religious devotion (v. 8) but also distinguishes this portrait of Job from the one we see of him in the coming dialogue.

2:1–10 Job’s Second Test Executed and Job’s Response. The text does not explicitly state that Satan expedites the tragedies in the first test (though we must assume it), but it does explicitly state that Satan afflicts Job with painful sores in this second test, which also includes the taunting by his wife (vv. 9–10a). Again Job passes the test. At the end of the first test, Job did not charge God with “wrongdoing” (1:22), and at the end of the second test, Job “did not sin in what he said” (v. 10b)—these are essentially two ways of saying the same thing. This is a supreme affirmation of Job’s trust in God; in the dialogue Job reaffirms this faith (13:15; 16:19; 23:10). Cf. Rom 8:18.

2:1–6 The second heavenly scene is almost a duplicate of the first, with the Lord’s significant commendation in v. 3b and Satan’s challenge in v. 4. Now that Job has passed the first test and proven Satan wrong, the follow-up is the claim that Job will give anything to save his own life (v. 4). In each test the Lord has a reservation: In the first test Satan must not harm Job’s person; in the second test Satan must spare Job’s life, though Job’s person is now vulnerable.

2:1 Like 1:6 but adds that Satan comes “to present himself before [the LORD].”

2:3 he still maintains his integrity. God recognizes the result of the first test. you incited me against him. God impugns Satan’s motives. While God cannot be incited to do things against his will, the fact that God asked Satan if he had considered his servant Job implies that the testing was part of the divine plan.

2:4 Skin for skin! A cryptic proverb perhaps equivalent to our expression “quid pro quo.” A man will give all he has for his own life. A second proverb that probably illuminates the meaning of the first proverb. Satan may be alleging that Job would give another person’s skin to save his own.

2:6 God prohibits Satan from taking Job’s life; i.e., God has not fully removed the hedge he built around Job (see 1:10 and note).

2:7 painful sores. Possibilities include leprosy and boils. The term is used of skin diseases in general in Deut 28:27.

2:8 scraped himself. Either to provide some relief from the malady or to lacerate his body as a sign of grief.

2:9–10 Job’s wife assumes the role of temptress and delivers to Job Satan’s threat that Job would curse God (v. 5b), but Job proves himself worthy of God’s faith in him.

2:11–13 Job’s Three Friends. Upon hearing of Job’s plight, his three friends plan to rendezvous and travel together to comfort him. The first two friends have connections, at least in name, to patriarchal figures.

2:11 Eliphaz. Means “my God is fine gold” or “my God is strength.” In the patriarchal period, Esau’s firstborn son is named Eliphaz (Gen 36:15) and comes from Teman, a region of Edom (Jer 49:7), which correlates with Job’s own Edomite origin. Bildad. Meaning uncertain. He is a “Shuhite,” which connects him by name to Shuah, the son of Abraham and Keturah (Gen 25:2). Zophar. Means “young bird.” The name occurs only in Job. He is a “Naamathite,” which indirectly connects him to the sister of Tubal-Cain (Gen 4:22). Since Job’s reputation was known throughout the East (1:3), it would not be surprising for his friends to be distantly located. met together by agreement. May imply that the three friends came from different regions. Their purpose, however, was the same: to “comfort” Job.

2:12 could hardly recognize him. Most likely because his suffering took a heavy toll on his physical appearance (cf. Isa 52:14; 53:3). weep aloud . . . tore their robes and sprinkled dust on their heads. Rites of mourning (Josh 7:6). Their apparent affection for their friend forms a baseline of friendship that the reader must take into account as the dialogue unfolds.

2:13 seven days. Customary period of mourning for a dead person (Gen 50:10). No one said a word to him. Mourners customarily did not speak until the sufferer spoke.

3:1–26 Job’s Lament. Satan’s challenge is that if God took away Job’s property and health, Job would curse God to his face (1:11; 2:5). Yet when Job speaks, his lament contains (1) a curse of his birth (vv. 3a, 4, 5, 11–19), (2) a curse of the night of his conception (vv. 3b, 6, 10), and (3) expressions of mourning about life in general (vv. 20–26). This sets the tone for the dialogue. Job is disoriented due to his indescribable emotional and physical suffering.

3:1 After this. After the seven days of silence. day of his birth. See 1:4.

3:2 He said. A shortened form of the Hebrew formulaic introduction to all of Job’s speeches: “And Job answered and said” (NIV “Job replied”; see 6:1; 9:1; 12:1; 16:1; 19:1; 21:1; 23:1; 26:1). The exceptions are 27:1 and 29:1, which read “Job continued his discourse.”

3:3 night. Perhaps evokes the negative imagery of Gen 1; its variants intensify the negative implications of Job’s birth (vv. 4, 5, 6, 7, 9). A boy is conceived! Announcement of Job’s birth is made by “the night” personified.

3:8 those who curse days. Professional magicians like Balaam (Num 22–24). Leviathan. See 41:1–10.

3:9 morning stars. Venus and Mercury; their appearance would have hailed the day of Job’s birth.

3:12 knees. May be those of the father, who received the child after birth (Gen 50:23); in Gen 30:3 they are those of the barren woman, who welcomed a surrogate’s child as her own. Job questions not only why his father was there to receive him but also why his mother survived the birth to nurse him.

3:13–15 Had Job not survived at birth, he would have joined the kings and princes of history who were lying in their graves “asleep and at rest” (v. 13).

3:16 Job asks why he was not stillborn.

3:17 There . . . there. Alludes to death and those who are “asleep and at rest” (v. 13). In Job’s mind that would have been a great improvement to this world.

3:19 slaves are freed from their owners. Suggests the author has a negative view of slavery. See also note on 31:13–15.

3:20–26 Job moves from the thought of death at birth to question why “those in misery” (v. 20) and “the bitter of soul” (v. 20) are still living. Though he longs for death and searches for it “more than for hidden treasure” (v. 21), it escapes him. But he will rejoice when it finally comes. His intense mourning is continual (v. 24).

3:23 whom God has hedged in. Dramatic irony, a literary device that gives the reader information the characters of the story do not have (1:10). Job perceives that God has hedged him in for a sinister rather than a benevolent purpose. Job misinterprets God’s purposes or is at least perplexed about them—a common motif in the dialogue.

4:1—27:23 The Dialogue. The friends speak in order of age and probably with regard to the weight of their arguments. Eliphaz’s three speeches are the longest and presumably the weightiest; Bildad’s three speeches are shorter and theologically lighter; Zophar speaks only twice, and his arguments are a bit more confused.

4:1—14:22 The Dialogue: Cycle One. A developing cycle of blame becomes evident: Eliphaz gently accuses Job of sinning; Bildad hastens to accuse Job of perverting God’s justice; Zophar insensitively claims that God has exacted of Job less than Job’s guilt deserves. Job, on the other hand, claims that he has done nothing wrong and is being treated unjustly by his three friends and by God, and that there is no mediator between him and God.

4:1—5:27 First Exchange: Eliphaz. Eliphaz articulates the basic thesis of the friends: an innocent person does not suffer (4:7–9). Then he goes on to suggest, quite positively, that the purpose of suffering is to put the offender back on the right road (5:17).

4:2 impatient. Though accusing Job of impatience, it is Eliphaz who is impatient with Job’s negative perspective on life (“But who can keep from speaking?”).

4:3–6 Eliphaz concedes that Job’s conduct has been exemplary, but this concession is brief; otherwise his allegations of Job’s impatience and lack of righteousness would not stand.

4:4–5 Eliphaz accuses Job of not taking his own advice.

4:7 While Job did not claim innocence in his lament (ch. 3), Eliphaz understands Job’s lament that way and replies to it as such. In the dialogue, the friends often read between the lines of Job’s speeches. The argument that the innocent do not suffer is impaired by Eliphaz’s insistence that there are no exceptions. Yet, sometimes the innocent do suffer. Consider now. Or “remember,” implying that Job already knew these things.

4:8 The principle of v. 7 (the innocent do not suffer) is considered from another angle: you reap what you sow (cf. Gal 6:7–8), a metaphor appropriate for Job, a farmer with 1,000 oxen (see note on 1:3).

4:9 God punishes the wicked and destroys them, a veiled threat to Job.

4:10 broken. The Hebrew for this word occurs only here in the OT; its meaning is inferred from the reference to lions’ teeth, which are incapable of taking prey (v. 11).

4:12–21 Eliphaz relates a terrifying dream he takes as an expression of truth. The thrust is that if God charges his angels with error, how much more so will he charge human beings (vv. 18–19).

4:17 Job did not claim to be “more righteous than God” (perhaps a bit of sarcasm), but Eliphaz infers this from Job’s lament. Eliphaz, by sharing his “revelation,” hopes to put the pronouncement beyond question.

4:19 crushed more readily than a moth! Moths are easy to catch and crush; humans, even easier.

4:20–21 The people who “live in houses of clay” (v. 19) are human beings (as opposed to angels, v. 18). Eliphaz stressed the weakness and moral vulnerability of mere humans; in speaking up for himself, Job casts his understanding of human beings in a broader moral vision. Here the friends make many insinuations about Job. None of the friends, however, even when speaking in the second person, use Job’s name, except the young, presumptuous Elihu (chs. 32–37).

4:21 cords of their tent pulled up. A metaphor for death.

5:1 holy ones. A carryover from God’s “servants”/“angels” (4:18). Eliphaz claims, as does Job also at first (9:33), that there are no heavenly beings to whom one may appeal—a thought Eliphaz repeats in 15:15. This probably alludes to the “sons of God” in chs. 1–2 (see note on 1:6), but Eliphaz knows nothing about them, only the angels of his dream.

5:2 Most likely a proverb Eliphaz uses to advise Job that overvexing himself about his troubles will get him nowhere.

5:3–5 Implies Eliphaz considers Job a “fool.” Eliphaz uses the emphatic personal pronoun (“I myself”) in v. 3 to shift attention to his personal experience.

5:3 his house was cursed. The loss of Job’s family may be the backdrop of vv. 4–5. Eliphaz is more subtle in his references to Job’s tragic loss than is Bildad (8:4).

5:7 Another proverb (cf. v. 2) that acknowledges suffering to be part of the human experience—so why be so upset about it!

5:8–27 Admitting that trouble is inevitable, Eliphaz still exhorts Job to seek God, whose work is overwhelming, providential, mysterious, avenging, impeding, and saving—all packaged together. Who can sort it out? But this much is clear: “Blessed [“happy” or “approved by God”] is the one whom God corrects” (v. 17). Eliphaz only suggests this disciplinary explanation for suffering, which God uses to turn the offender back on to the right track (cf. Prov 3:11–12), but Elihu further develops it (33:14–17; 37:13). This part of the speech contains several allusions to Job’s personal tragedy: “the sword” (vv. 15, 20), “destruction” (vv. 21, 22), “your property” (v. 24), “your children” (v. 25).

5:13 Quoted in 1 Cor 3:19 to warn those pretending to be wise that God honors no such pretense but “catches the wise in their craftiness.”

5:17 discipline. Implies preventive rather than punitive action (36:10). Almighty. Hebrew šadday; a name used for God in the patriarchal era (e.g., Gen 17:1); most of its occurrences are in Job, perhaps suggesting the age of the book or the author’s retrogression of the story into the patriarchal era. Its etymology is obscure.

5:18 he wounds, but he also binds up. Admission that God does allow harm to his children, but he also heals them (cf. Hos 6:1).

5:19 From six calamities . . . in seven. God is a rescuing God. The numbers are poetic and not to be taken as exact.

5:24 find . . . missing. One of the basic Hebrew root words for “to sin” (ḥṭ ʾ ); it means “miss the mark” and is used of an old man who yet fails to reach his full quota of years (Isa 65:20) and of missing the path in haste (Prov 19:2). The metaphor is painful for Job since he has lost everything.

5:27 Eliphaz gives the knife in Job’s heart one more twist: he demands that Job listen and apply this lesson to himself.

6:1—7:21 Job’s Response to Eliphaz. Job retorts that his complaint is not baseless—there is a reason for it! One of Job’s basic allegations: God has caused his suffering (6:4). Further, Job makes explicit what Eliphaz perceived as implicit: Job claims to be innocent (6:28–30). This speech reveals Job’s emotional pain (6:2–3) as well as his physical suffering (7:5; see 19:20; 30:30). As Eliphaz began his first speech somewhat apologetically (4:2a), Job too seems reluctant to engage his friends in debate because he is afraid of what he might say (6:8–10). If God would just “cut off [his] life” (6:9), then he would have the “consolation . . . that [he] had not denied the words of the Holy One” (6:10), suggesting perhaps the Lord’s assessment of his righteous character in 1:8; 2:3. Job does not know what went on in the heavenly council, but the reader does. At times, as here, Job exhibits an intuitive knowledge that only God and the reader have: apart from any deviations that might follow, Job’s initial affirmations of faith (1:21; 2:10) will stand, and God’s character assessment of him will continue to be valid.

6:2–3 The reason Job’s “words have been impetuous”: if weighed, all his misery would be heavier than “the sand of the seas.”

6:4 arrows of the Almighty. For God as an archer, see Deut 32:23; Pss 7:13; 38:2; 64:7; Lam 3:12–13; Ezek 5:16. Here his arrows are poisonous (doubly effective).

6:5 Does a wild donkey bray when it has grass . . . ? A rhetorical question that assumes the answer “yes.” So too a human being will cry out when in pain.

6:6-7 tasteless food . . . makes me ill. Does not seem to apply to Job’s affliction, so it must refer to Eliphaz’s argument.

6:8–10 Job wants to die; he hopes God will, like a weaver, “cut off” (v. 9) the thread of his life.

6:11–13 Job, physically and emotionally exhausted, has no strength to continue, which is perhaps an objection to beginning this debate in the first place.

6:14–30 The “friendship” (see v. 14) represented here has begun to unravel, and Job equates withholding “kindness from a friend” with forsaking “the fear of the Almighty” (v. 14). Like wadis that surge during the rainy season and “stop flowing in the dry season” (v. 17), thereby proving undependable to caravans that seek water but find only dry tributaries (vv. 18–20), Job accuses the friends (using the plural “you,” v. 21) of being as false to him as dry wadis are to caravans. Yet Job never asks them for favors (vv. 22–23).

6:21 see . . . are afraid. A wordplay: in Hebrew these words sound alike.

6:24–27 Job challenges his friends to correct him, and he “will be quiet” (v. 24). Though Eliphaz has insinuated that Job is being punished for his sin (4:7), Job does not admit it and says, “Show me where I have been wrong” (v. 24). A friendly encounter has become an all-out debate about Job’s character and his reaction to the tragic events of his life. But with friends who “would even cast lots for the fatherless” (v. 27), Job is not optimistic about the outcome.

6:28–30 Eliphaz appears to be speaking to Job without looking at him, a mark of respect in ancient Near Eastern culture. But Job demands that his friends “look at” him (v. 28), perhaps to better understand and to see his physical contortions, which are an index to his emotional trauma (7:5–6).

7:1–10 Job’s emotional and physical suffering cause an erratic pattern in his speeches. Sometimes he addresses the friend who just spoke or all of the friends; at other times, without warning, he addresses God directly; at still other times, he moves quite unnoticeably into a monologue. Here he addresses God (v. 7) and describes his life with metaphors: the hard life of a day laborer (vv. 1b, 2b), a slave longing for evening to come (v. 2), the swiftness of a weaver’s shuttle (v. 6), a breath (v. 7a), and a vanishing cloud (v. 9). He believes his death is imminent, yet he turns his attention momentarily to the general plight of humankind. Putting his personal tragedy in the larger context of others’ suffering shows that Job has begun the arduous journey to healing.

7:2 hired laborer. See Deut 24:15.

7:3 months. A hint of either how long Job’s ordeal has been going on or his anticipation of the long ordeal ahead.

7:8 God will look for Job, but Job will not be there for God to use him as a target (v. 20b; 6:4).

7:11–16 Despite his trouble, Job is determined to speak and not keep silent. Why would God frighten him with dreams rather than let sleep provide him with relief from his suffering?

7:17–21 Again, attention is given to the plight of humanity (cf. v. 1). Why are human beings so important to God that he makes such sport of them? Job intuitively recognizes that God is testing him. He again reminds God that he is about to die, so why does God not just pardon his sins and let bygones be bygones (v. 21)?

7:17 A similar question to Ps 8:4 but with a different intent. Ps 8 questions human worth in light of God’s marvelous creation; Job asks why man is so important that God would, as it were, use him for target practice—man’s not worth it.

7:19 even for an instant. Also can be worded, “till I swallow my spittle.” God does not give him time even to swallow before he starts his target practice again.

8:1–22 Second Exchange: Bildad. Bildad’s speech is much shorter than Eliphaz’s, perhaps suggesting declining importance of the arguments as well as his younger age (see note on 4:1—27:23). He confines himself to the third part of Job’s speech, the bitter lot of humanity. Bildad, seemingly provoked by Job’s accusation of God, defends the Almighty (v. 3) This topic dominates Bildad’s whole speech, and he affirms Eliphaz’s contention that God does not reject an innocent person (v. 20; 4:7).

8:2 How long will you say such things? Already Bildad is impatient. blustering wind. Suggests Job’s words are noisy but empty.

8:3 pervert justice. This is not what Job said, but Bildad understands Job’s words that way. Job said that God treated him harshly (6:4), thus unjustly.

8:4 Brash and insensitive, Bildad says Job’s children got what they deserved.

8:5 seek God earnestly. Cf. Eliphaz’s call to repentance (5:8). If Job is “pure and upright” (v. 6), God will take action and restore Job’s prosperity.

8:8–10 Bildad insists that reviewing the past will provide answers his generation is unable to give since each generation passes as quickly as a “shadow” (v. 9). The accumulative wisdom of past generations will “instruct” Job (v. 10).

8:11–19 Three illustrations from nature: (1) The papyrus plant, useful for baskets and writing materials, grows in marshy areas, but when the marsh dries up, it withers and is useless; thus is the lot of those who forget God (vv. 11–13). (2) The spider’s web gives flimsy support when leaned on; such is the wicked person’s hope (vv. 14–15). (3) A plant sends its roots down around stones and secures its place, but when it is pulled up, the garden disowns it and it withers; such is the fate of the wicked (vv. 16–19). These metaphors allude to Job; the last one articulates Job’s sense of alienation, which he puts into words in 19:13–19.

8:20 God does not reject one who is blameless. Based on his earlier admonition (vv. 6–7), Bildad holds out hope that Job will be restored to his former happy condition (vv. 21–22).

9:1—10:22 Job’s Response to Bildad. Job’s second speech responds to both Eliphaz and Bildad, quite characteristic of Job’s style. Eliphaz spoke of God’s grandeur (5:9), and Job repeats those words (9:10) but says God is elusive to him (9:11). To his credit, Job does not retort—at least not yet—with the same kind of personal impudence as Bildad. At this point Job is more focused on God than his friends, and he raises the objection that a mere human being cannot meet God on his own terms (9:3, 32). Moreover, God is all-powerful (9:3–12) but incomprehensible at times (9:22)—at least that is Job’s opinion at this stage of the argument. In the absence of a fair hearing before God, Job refutes the idea that there is a mediator who can stand between him and God (9:33). God’s problem (mark Job’s insolence!) may be that he does not understand how it feels to be human (10:4–7). Job again declares his innocence (10:7).

9:2 I know that this is true. Job acknowledges Bildad’s assertion that God is just (8:20–22).

9:9 Job acknowledges God as Creator of the constellations, here identified as the “Bear,” “Orion,” and “Pleiades.” constellations of the south. Suggests the chambers of the south wind (Ps 78:26).

![]()

![]()

9:11–12 Job says that for a God whose creation is so wonderful, God certainly keeps himself out of reach of his human creatures, particularly out of his (Job’s) reach.

9:13 Rahab. Figurative name for Egypt (Ps 87:4; Isa 30:7). Thus, “the cohorts of Rahab” might be the armies of Egypt that were defeated at the Red Sea. Some, however, take Rahab to be a mythological creature of the sea, along with Leviathan (3:8; 41:1–34). Even so, there is no evidence that Job espouses a full-fledged mythology of the ancient world, because his God has no competitors.

9:14–15 Job returns to the topic of God’s elusiveness in the conduct of an argument (v. 11). If God does not want to be found and is determined to win the argument, there’s not much a mortal can do about it.

9:16–18 The setting is the law court, and Job sees God as both judge and executioner.

9:20 Even if Job were innocent (he is sure that he is), God would be so overpowering in the courtroom and Job so weak and confused that Job’s own mouth would pronounce him guilty. There is no way to win a case against this Prosecutor.

9:21–24 Job claims innocence (also in 10:7) and declares God incomprehensible (v. 22). Job even perceives that God mocks those who are victims of calamity and blindfolds the faces of their judges, but Job holds open the possibility that he could be mistaken (“If it is not he, then who is it?” [v. 24]).

9:25–31 Job returns to lamenting his own life, using three metaphors to describe his hasty demise: “swifter than a runner” (v. 25), “skim past like boats of papyrus” (v. 26), and “like eagles swooping down on their prey” (v. 26). He feels doomed by his affliction and by God’s preemptive verdict of “guilty” (v. 29).

9:32–35 When it comes to the deity, Job’s humanity is a liability (v. 32), so Job longs for a mediator (v. 33). While this mediator might not have divine status, he would have to be in a position to arbitrate between God and Job.

9:33 someone to mediate between us. While Job longs for a mediator between him and God, he is not at all confident that such a mediator exists. But he eventually becomes more confident that his “advocate is on high” (16:19). In 19:25 he affirms that he does have an advocate. someone to bring us together. I.e., someone to arbitrate in such a way that both agree to the terms of the decision.

10:2 Job’s address turns from the friends to God.

10:3 In 9:22 Job accused God of caring for neither right nor wrong. Here Job charges God with favoring the schemes of the wicked.

10:4–7 Four rhetorical questions focus on Job’s thoughts regarding God’s inability to understand what it is like to be human (vv. 4–5). Their implied answer is “no.” God cannot understand what it feels like to be hemmed in on one side by birth and on the other side by death. The idea is that if God could understand Job’s humanness, God would not “search out [Job’s] faults and probe after [his] sin” (v. 6)—even though God knows that Job is not guilty. Yet Job is helpless: “no one can rescue me from [God’s] hand” (v. 7).

10:8–12 Using the figure of God as a potter and Job as clay (vv. 8–9), Job wonders how he is to understand the enigma of the Creator treating his creation so badly. Job sees God as his enemy, and Job is helpless to do anything about it except to plead as strongly as he can.

10:13–17 Job thinks that God has concealed a miserable plan for him and that God has always been watching for any sin, stalking Job like a lion.

10:18–22 Job returns to lamenting why he was not stillborn (cf. ch. 3). He pitifully pleads for God to give him a moment’s joy before he dies (v. 20).

11:1–20 Third Exchange: Zophar. Zophar minces no words with Job and even intimates that the first two speakers have not sufficiently answered Job (v. 3). He contends that God has exacted of Job less than Job’s guilt warrants (v. 6), and like the other two friends (5:8; 8:5–7), he challenges Job to acknowledge his sin and seek God. If Job will do so, God will have mercy (vv. 13–19). But if Job will not do so, he is lost (v. 20)!

11:1 Zophar the Naamathite. Cf. 2:11.

11:2 Like Bildad (8:2), Zophar refers to Job’s words to justify his response, calling Job a “talker.”

11:3 idle talk. Zophar hears contempt in Job’s words (“when you mock”; cf. Prov 30:17), and he wonders why neither of the friends has properly rebuked Job for his insolent babble.

11:4 This is Zophar’s version of Job’s claim to innocence.

11:5–6 If God would speak, he would reveal the other side of “wisdom”: that Job’s sins are so numerous that God cannot even remember them all.

11:7–9 Skeptically, Zophar indicts Job for assuming that he can comprehend God, who is without “limits” (v. 7). Theologically, Zophar is right, but practically, Job—who is shut up in his world with God and his indescribable suffering and who has no cause to explain it—must try to explore the limits of a world where justice and God meet, if there is such an overlap.

11:10 confines . . . in prison. Translates a verb used of a leper who is quarantined (e.g., “isolate” in Lev 13:5, 11, 21, 26, 31); here Job’s afflictions metaphorically confine him. convenes a court. Suggests a court of law where God is a perceptive judge who recognizes evil.

11:12 This is probably a proverb, but its meaning is difficult (see NIV text note). If this alludes to Job, it is caustic, which would not be surprising on the lips of Zophar.

11:13–20 Like Eliphaz and Bildad (5:8; 8:5), Zophar calls Job to repentance, which Zophar says would result in a happy, secure, and socially productive life (cf. note on 8:5). But for Job to confess sin in order to have God’s blessings would undermine Job’s integrity and prove correct Satan’s claim that Job fears God for selfish motives (cf. 1:9; 2:4).

12:1—14:22 Job’s Response to Zophar. Job sarcastically indicts his friends because of their petty claim to wisdom (12:2–3). His attention turns more and more toward God. Job wants to make his case before the Almighty, hoping that his friends will keep silent now that the dialogue has run its course (13:3–5). Job’s only hope is that God is just (13:16).

12:2 Job sarcastically indicts the friends (plural “you”) for assuming they have a monopoly on wisdom.

12:3 This could be motivated by Zophar’s reference to a “wild donkey’s colt” (11:12).

12:4 laughingstock. There is no evidence that the friends have laughed at him, but they have certainly been derisive.

12:5–6 Job explains their derision: they have not experienced his affliction.

12:6 those God has in his hand. The meaning of this clause is uncertain. The NIV interprets it to mean that the “marauders” are undisturbed in God’s hand (while Job is terribly troubled). Others view it to mean that the marauders have made a god out of their own power (“hand”; see NIV text note). However, since there is virtually no reference to idolatry in the dialogue, the NIV interpretation is preferable.

12:7–12 Job responds sarcastically to Zophar’s disparaging words in 11:7–12, where Zophar contends that the universe is too mysterious for humans to understand and that so far as wisdom is concerned, man is comparable to a “wild donkey’s colt” (11:12)—he’s not very wise! Job turns the argument on Zophar and asserts that even the animals are wiser than humans. Metaphorically speaking, Job takes the enemy’s sword in his own hand and fights with it.

12:9 that the hand of the LORD has done this. Echoes Isa 41:20.

12:11 This is probably a proverb; Elihu quotes it in 34:3 to justify his appraisal of the friends’ speeches.

12:12 Is not wisdom found among the aged? Sarcasm, which fits the mood of Job’s speeches.

12:13–25 Job insists that God is the only viable possessor of wisdom, yet as the Sovereign over all things, both good and evil, his wisdom is neither so deep as to be unfathomable nor so contradictory as to be beyond understanding. Yet we are still too early in the dialogue to accept this position as the author’s view of God. If we perceive the author’s theology to follow the lines of Job’s arguments, then we must understand his method to involve false theses and false antitheses.

12:15 God is in complete control of nature.

12:16 both deceived and deceiver are his. All of nature is under God’s control (cf., e.g., Jer 4:10; 20:7; Ezek 14:9).

13:1–2 Job defends his own knowledge and asserts that he is not inferior to his friends, which they have implied.

13:3 Here at the end of Cycle One (see note on 4:1—14:22), after all three friends have spoken, Job insists that he wants to argue his case before God, not before his friends. Indeed, if they will be silent, that will be wisdom (cf. Prov 17:28). Job seems to hope that this is the end of the discussion (v. 5).

13:7–12 Job faults the friends for arguing “the case for God” (v. 8). Later, God himself also indicts Job, saying, “You condemn me to justify yourself” (40:8).

13:11 Zophar said that if God should speak, he would rebuke Job (11:5–6). Job counters that if God did speak, it would “terrify” Zophar and his two companions (“you” is plural).

13:13–19 This is a change in Job’s tone and is, in fact, a significant turn in the argument, at least from Job’s perspective, for Job is quite confident that he will be vindicated (v. 18). While Job’s wife and friends have deserted him and he is shut up in his world with God, sure of his innocence (v. 16b), Job is slowly turning from his adversarial position to one of trust (v. 15). From now on Job’s speeches are characterized by a tone of trust—but not entirely, for he is still a troubled man.

13:15 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him. Note Job’s shift of confidence in God’s favor (see vv. 16, 18).

13:18 In Job’s mind, and also in the substance of his arguments in his three speeches of Cycle One (see notes on 6:1—7:21; 9:1—10:22; 12:1—14:22), he has “prepared” his case. prepared. The Hebrew verb is usually used of military preparations. Applied to an argument, it is peculiar to Job (23:4; 32:14; 33:5; 37:19).

13:19 Can anyone bring charges against me? Some suggest that this is the opening formula of a plaintiff in a court of law. Cf. Isa 50:8.

13:20–28 Characteristic of Job’s shift in emotions and language, he turns from the friends to God.

13:20–22 Job makes two requests of God: (1) “Withdraw your hand far from me” (i.e., stop frightening me with your terrors), and (2) “Let me speak, and you reply to me.”

13:23 In 10:4–7 (see note there) Job accuses God of stalking him for his sins; here he asks God to make an accounting of his sins if he has any (i.e., bring a bill of indictment against him).

13:24 hide your face. An idiom that here means “to be hostile” (cf. Num 6:25 for the opposite idiom).

13:25 windblown leaf . . . dry chaff. Metaphors of helplessness and fragility in the presence of God’s overwhelming power.

13:26 sins of my youth. When Job claims innocence, he seems not to include these, probably because he considers them forgiven.

13:27 shackles. Job’s description of God’s ill-treatment of him. marks on the soles of my feet. Probably marks from the shackles.

![]()

![]()

14:1–22 Job returns to the brevity of human life and its misery (cf. 7:1–10, 17–21) and sets his personal situation in that context (vv. 13–17).

14:2 Job compares human life to “flowers” that “wither away” and to “fleeting shadows.” Neither lasts very long.

14:3 In view of the ephemeral nature of humanity, it seems to Job unworthy of God to pursue such a defenseless creature.

14:5 Stresses the limitations of human life (cf. 10:1–7).

14:6 hired laborer. His days are miserable enough without God introducing complications.

14:7–17 A dying tree may sprout again if it is cut off close to the ground. In comparison, “man dies . . . and is no more” (v. 10). Job hints that he does not accept the concept of life after death. Verses 13–17 put the object lesson of the dying tree in personal terms: “If someone dies, will they live again?” (v. 14). It is essentially a rhetorical question whose answer is “no,” at least so far as Job is concerned at this point. It is not clear whether Job has the same conception of resurrection described more fully in the NT (in 19:26 there is such a possibility). Some take “my renewal” (v. 14) to imply this, but he is definitely speaking of the continuation of life after death.

14:14 If someone dies, will they live again? His tentative answer to the question is that if he were assured of a positive answer to the question, he would wait through his miserable life until that moment came (v. 14b). But he is not yet confident of that hope (cf. 19:25–27). hard service. Reveals how Job views his life.

14:15–17 If life after death were a reality (suggesting a continuing relationship between God and man), then that relationship in this life would be far more cordial (v. 15), and God would “count [Job’s] steps” (implying thoughtful care) and “not keep track of my sin” (v. 16).

14:18–19 Under God’s direction, humanity’s hope erodes like the mountains under nature’s power.

14:21 children. Of the dead; alludes to Job’s terrible pain when remembering his children’s fate. This is one of the few hints about his children. Perhaps their death was too painful to discuss, so he mentions it only indirectly.

15:1—21:34 The Dialogue: Cycle Two. Eliphaz insists that Job’s own words have condemned him, a theme shared by his colleagues. Job turns less toward his three friends, who are more and more caustic, and turns more toward God, insisting that there is someone in heaven who vouches for his innocence.

15:1–35 First Exchange: Eliphaz. Eliphaz’s second speech is not as conciliatory as his first was. He begins by questioning Job’s wisdom (v. 2a). Eliphaz previously phrased the issue of Job’s innocence in a rhetorical question (4:7). But here he is more direct (v. 6a). Moreover, in his first speech (4:6), Eliphaz held that Job’s “piety” (i.e., “fear” of God) was his confidence, but here Eliphaz accuses Job of undermining “piety” (see v. 4 and note). Sometimes Job and the friends seize each other’s words and, metaphorically speaking, fight with each other’s sword, illustrated here by Eliphaz’s use of Job’s arguments. For example, Job claimed that he has as much understanding as the friends have and that he is not inferior to them (12:3). Put on the defensive, Eliphaz makes the same claim (v. 9). Eliphaz sounds offended that Job did not respond to the gentleness of his first speech (v. 11). Eliphaz raises an argument that he used in the first speech (4:17–19)—that humans cannot be righteous before God—and he uses it to indict Job. This is probably the most direct indictment of Job anywhere in Eliphaz’s first two speeches.

15:2–3 According to Eliphaz, “a wise person” (which Job claims to be [12:3; 13:2]) would have better arguments than Job’s. Job is filled with “the hot east wind” (what is known today as the hamsin, which brings heat and sand).

15:4 piety. Hebrew “fear”; a shortened form of “the fear of God/the LORD.” Job uses an altered longer phrase in 6:14 (“the fear of the Almighty [Hebrew šadday])” and 28:28 (“the fear of the Lord” [Hebrew ʾ ădōnāy]). The longer phrase occurs frequently in Proverbs (e.g., Prov 1:7) and elsewhere (e.g., 2 Chr 19:9; Ps 19:9).

15:6 Compared to his gentle approach in ch. 4, this is as gentle as Eliphaz gets in this speech. Rather than Eliphaz’s condemnation, Job’s own mouth condemns him.

15:8 By dramatic irony the reader knows that God has held a council (1:6; 2:1) that Job is not privy to (cf. 3:23 and note).

15:10 In Cycle One (12:12), in a tone of refutation, Job quotes the friends’ positive view of the relationship of age and wisdom, but Eliphaz is perturbed about Job’s view, noting that their age is a positive factor.

15:11 Eliphaz identifies his gentle and comforting words of 4:7–11 as “God’s consolations.”

15:14–16 If God does not trust “his holy ones” (v. 15), why would he trust human beings? This reference to some heavenly rebellion (cf. Isa 14:12–20; 2 Pet 2:4) virtually duplicates Eliphaz’s argument in 4:18–19.

15:20–35 Describing the wicked man is a feature of wisdom literature, and the book of Job is no exception. Here it is likely a veiled reference to Job. Eliphaz in effect asks, “Do the wicked really suffer for their sins?” Job answers differently than his friends. Eliphaz offers the first explanation of the wicked person’s fate: he spends his life in pain and in constant fear that he will suddenly lose his wealth (vv. 20–21).

15:21 In 12:6 Job contended that “marauders” prosper. Eliphaz may be answering him, but with more subtlety; he has Job in mind.

15:24–26 Tacitly describes Job.

15:25 shakes his fist at God. Metaphorically describes Job’s defiant attitude as Eliphaz perceives it.

15:32–33 Eliphaz compares the wicked to a tree that withers, a vine that bears no fruit, and an “olive tree shedding its blossoms” (v. 33). The olive tree has numerous blooms, only a few of which become fruit, suggesting a loss of hope. Job submitted his question about the afterlife (14:7–17), which was at the same time a veiled hope, and Eliphaz discourages his speculation.

16:1—17:16 Job’s Response to Eliphaz. This speech, like Job’s others, directly addresses the friends only in part (e.g., 16:2–5 and possibly 17:10), with another part addressed to God (16:7–8; 17:3–4). Job apostrophizes the earth (16:18), while much of the speech is a monologue (16:6–17, 20–22; 17:1–2, 5–9, 11–16). Job begins this speech by addressing all of the friends, not just Eliphaz, saying, “You are miserable comforters, all of you!” (16:2). Job evidently hopes that the friends will leave him alone (13:5), but now that Eliphaz has shattered that hope by starting a second round of speeches, Job turns to him (“you . . . you” in 16:3 are singular). Job continues to maintain his innocence (16:17). Just as Job shifted in a positive direction in his final speech of Cycle One, here his view significantly changes regarding a mediator between him and God. Although he had disavowed such a mediator (9:33), he is confident, at least for the moment, that his “witness” represents him “in heaven” (16:19). With sharpening spiritual insight, Job thinks of a way for God to show him that he is concerned about him and will vindicate him: God could himself become a “pledge” for Job (17:3). Much like 10:4–7 represents his spiritual depth (perhaps pointing in the direction of the incarnation), Job points in the same direction—when Christ became a “pledge” for us (see “guarantor” in Heb 7:22). See note on 10:4–7.

16:2 miserable comforters. The friends’ arguments have become repetitive and their ideas specious.

16:4 Job hypothesizes that if the roles were switched, he could also talk like the friends.

16:7 Job addresses God, and most of the remainder of the speech is about God, though not addressed directly to him.

16:8 gauntness. Evidence that God has assaulted Job.

16:9 my opponent. Some see this as a reference to Satan, but it likely refers to Job’s human opponents (v. 10).

16:11 The friends made allusive references to Job; here Job refers to them as “the ungodly” and “the wicked.”

16:16 Involuntary weeping is sometimes connected with leprosy, a disease some think Job had. However, Job’s troubles are enough to cause this condition without attributing it to leprosy.

16:17 Job still insists that he is innocent.

16:18 Unavenged “blood” spilled on the ground cries out for vengeance (Gen 4:10), so Job commands the earth not to cover his unavenged blood in the hope that vengeance will eventually come.

16:19–21 Job now believes he has a “witness [who] is in heaven” who serves as his “advocate” (v. 19). Cf. 9:33. Job addresses the friends and informs them that his appeal is to God, not to them.

17:2 Job acknowledges that he must endure “their hostility.”

17:3 See note on 16:1—17:16.

17:4 In this brief appeal to God, Job prays that his friends’ arguments will not prevail (see Pss 30:1; 41:11).

17:5 This may be a proverb.

17:7 Physically, Job is a mere shadow of his former self.

17:8 the upright are appalled. May be a satirical jibe at his friends (as v. 10 clearly is). this. Job’s condition. But even though the friends are not appalled, Job, the righteous man, will cling to his way (v. 9).

17:11–16 Job contemplates the end of his life.

18:1–21 Second Exchange: Bildad. As in Eliphaz’s second speech, the social courtesies are over. Bildad begins by claiming that Job looks on the friends as no more than stupid cattle (v. 3). Following Eliphaz’s example, Bildad offers a long description of the wicked man (vv. 5–21), perhaps an oblique reference to Job, adding that the wicked know nothing but terror and suffering (vv. 11–13). The hints that Bildad is describing Job are references to Job’s skin disease (v. 13; see 2:7–8), the “burning sulfur . . . scattered over his dwelling” (v. 15; cf. “the fire of God” in 1:16), and the loss of family (v. 19; cf. Bildad’s reference to Job’s children in 8:4). Again we have a word picture of Job’s suffering as he scrapes himself with potsherds (v. 4).

18:2–4 Bildad addresses Job in the plural since Job indicated that others hold his opinion (17:8–9).

18:5–21 The friends embrace the doctrine of retribution (see also Prov 13:9; 20:20; 24:20), which Job has questioned. The undergirding principle of Bildad’s speech is that the wicked man’s “own schemes throw him down” (v. 7). The final judgment is that Job “does not know God” (v. 21).

18:13 This pictures Job’s skin-eating disease.

18:17 Alludes to Job’s loss of reputation and perhaps also the loss of his children, to whom v. 19 explicitly refers.

19:1–29 Job’s Response to Bildad. Job again addresses all of the friends rather than the one who has just finished speaking: “How long will you [plural] torment me and crush me with words?” (v. 2). Job returns to the idea of God as his enemy, leading his troops against Job (vv. 6–12). In a pitiful description of his social position, Job laments the breakdown of all his social relationships—even young children despise and talk about him (vv. 13–19). Then, in a moment of desperation, he pleads with his friends to have pity on him (vv. 21–22). Once more the text describes Job’s physical condition: emaciated by his disease, he looks like skin stretched over a skeleton (v. 20). Then comes a climax of spiritual insight as Job contemplates what it would mean if his words were permanently recorded in a book as a record preserved for the day of vindication. As in 16:19 (where he expresses the confidence that his “witness is in heaven”), Job declares in a confidence not attained up to now, “I know that my redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand on the earth” (v. 25). For the first time, he expresses the belief that he will be vindicated after death.

19:3 Ten times. There have not been ten speeches by the friends so far, so this must be figurative (cf. Gen 31:7; Num 14:22).

19:4 Not admitting guilt, this is a conditional statement: “even if I erred, my error would remain with me, not with you.”

19:5–22 This honestly, if not caustically, indicts God, whom Job believes has caused all his woes, which include the social and familial breakdown of his relationships (vv. 13–19). So reversed are they that he must even supplicate his slave rather than give him orders (v. 16).

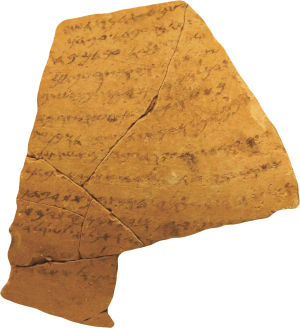

19:23–24 Resignation is sometimes mistaken for hopelessness, and Job, resigned to his pitiable lot, is still indomitable in his desire to present his case to God. But since God will not confront him personally, Job prefaces his hope for a redeemer by desiring that his words be recorded “on a scroll” (v. 23) or “engraved in rock forever” (v. 24), anticipating the day of vindication.

![]()

![]()

19:25 This is one of the most beloved verses in Job. Many Christians through the centuries have appropriated this verse as a precious hope in the afterlife. The “redeemer” in Israel could ransom those sold into slavery (Lev 25:47–55), redeem property (Lev 25:23–24), avenge the blood of a kinsman (Num 35:19), and preserve the line of a deceased relative (Deut 25:5–10). While the term usually refers to a human being, sometimes God is called a redeemer (Exod 6:6; 15:13; Ps 103:4). Job had wished for “someone to mediate between us” (9:33), and he has come to believe that he has a “witness . . . in heaven” (16:19). Now he is confident that God is his redeemer. will stand. Comes from the law court, where one appears as a witness, in this case, for the defendant.

19:26–27 Another reference to Job’s deteriorating flesh. Yet when this has happened, Job “will see God.” What he had hoped for, even demanded, is now within faith’s grasp. The baseline is that he now believes in life after death, although “in my flesh” (implying a bodily resurrection) can also be rendered “apart from my flesh” (see second NIV text note on v. 26) and imply consciousness after death but not the bodily resurrection. But there are two clear references in the OT to the bodily resurrection: Isa 26:19; Dan 12:2.

20:1–29 Third Exchange: Zophar. Given how blunt Zophar is, we should not be surprised that he makes his second speech and then does not speak again in the third cycle—he had already said everything! His forthright manner of speaking leaves no doubt that he believes Job is guilty of gross sins and is a wicked man. Like the other friends, he never mentions Job by name (he talks only about the wicked man in general), but he obviously has Job in mind. Eliphaz introduced the idea of the prosperity of the wicked (15:20–35); Bildad had picked up on it; and Zophar follows suit. His explanation for the prosperity of the wicked is that it is brief and that judgment will catch up with him (v. 5). Humankind and the universe are so structured that wickedness cannot be tolerated (vv. 16, 27).

20:3 a rebuke that dishonors me. Job’s words personally offended Zophar.

20:12–14 Evil is like a tidbit that, when taken upon one’s tongue, turns to poison.

20:15 God causes the wicked person to disgorge their ill-gotten gain.

20:19 Zophar, anticipating Eliphaz’s third speech (ch. 22), spells out Job’s sins: “he has oppressed the poor . . . seized houses he did not build.”

20:24 bronze-tipped arrow. A more deadly weapon than other types.

21:1–34 Job’s Response to Zophar. Job countercharges the allegations of his friends—the wicked do not really prosper, their prosperity is only apparent, and their prosperity is temporary: “the wicked live on, growing old and increasing in power” (v. 7). Job is preoccupied with this thought throughout the speech. It is his strongest and clearest statement on the matter. He closes with a direct indictment that anything else the friends could say would be only falsehood (v. 34). That should be a strong hint that he would like to end the conversation right there, but, alas, Eliphaz has still more to say.

21:5 clap your hand over your mouth. A gesture of awe.

21:7–16 Job’s description of the prosperity of the wicked, i.e., the wicked prosper, their children prosper (vv. 7–8), and they live a happy life and die in peace. The full description is essentially the reverse of Job’s own situation.

21:17–34 Job continues to lay out the case for the prosperity of the wicked. His experience is that they get away with their wicked schemes without repercussion. One explanation is that the next generation suffers for them (v. 19a), when the present generation are the ones who deserve to be punished (vv. 19b–20). Exod 20:5 expresses the principle of retribution upon the children, but Deut 24:16; Jer 31:29–30; Ezek 18 reverses that principle.

22:1—27:23 The Dialogue: Cycle Three. The friends have either turned their accusations into real indictments of immoral conduct (Eliphaz), reduced Job as a person to something less than human (Bildad), or altogether given up on him (Zophar). Job, on the other hand, contends that if he could only find God, God would listen and acquit him, and Job would “come forth as gold” (23:10).

22:1–30 First Exchange: Eliphaz. Eliphaz makes a complete turnaround. In this speech he even details the sins of Job, although in the first speech he merely derided Job for being impatient when the adversities he had seen in other people’s lives had come to him (4:4–5). Now, however, he accuses him of exacting pledges, taking the clothing of the poor, refusing to feed the hungry, and showing no compassion for widows and orphans (vv. 6–9).

22:2–3 Job accused God of having an ulterior motive in his dealings with him. Eliphaz insists that Job can bring no benefit to God, so why should God have an ulterior motive? Elihu says the same thing in 34:9, and Job said it with another meaning in 7:20. God gets no benefit if we sin or if we are righteous, so he is the only one who has no ulterior motive. In one sense, Eliphaz is right, because God does not receive any benefit personally; but in another sense, he is wrong, because God initiated this entire process of suffering so that he could prove to Satan that there is at least one man in the world who serves God with absolutely no ulterior motive.

22:4 piety. The Hebrew word is sometimes translated “fear” (of God). Sometimes the friends sarcastically stumble upon the truth, which, of course, they do not recognize, and this is such an instance. Yes, it is for Job’s fear of God that he is suffering (1:1), although Eliphaz frames it in negative terms: God “rebukes . . . and brings charges against” Job. Yet with dramatic irony the reader knows the truth from having listened in on the heavenly council in the prologue.

22:5 In Cycle One Eliphaz essentially insisted that all human beings sin; in Cycle Two he became a bit more personal and accused Job of showing himself to be a sinner by his own bitter words; in Cycle Three he takes the next step and catalogs Job’s specific sins (vv. 6–9).

22:6–9 The verbs here occur frequently, indicating that this was Job’s ongoing practice. Eliphaz claims that despite all his wealth Job (1) took the poor man’s garment as a pledge of loan repayment (“security,” v. 6) and left him naked, whereas the law stipulated that he should return it before sundown (Exod 22:26; Deut 24:10–13); (2) refused food and water to the hungry (Isa 58:7, 10); (3) confiscated land that did not belong to him (Isa 5:8); and (4) oppressed the widows and orphans in violation of the law that instructed compassionate care for them (e.g., Deut 24:19–21).

![]()

![]()

22:11 Still in his personal-indictment mode, Eliphaz applies the lesson of Bildad’s speech (18:8–10) to Job directly.

22:12–14 God’s transcendence can mean that either (1) he is so distant that he cannot know what is going on in the world, or (2) he is so high that he has a perfect perspective on all that goes on in the world. Eliphaz suggests that Job assumes the former.

22:15 old path. In Jer 6:16 it is the good way, but here it is the path of the wicked.

22:17 Using the same words (“Leave us alone!”) but from the other end of the process, Job argued that those who dismiss God from their lives prosper (21:13–14). Eliphaz argues from the outcome of the process that those who dismiss God from their lives come to ruin. Job is his object lesson.

22:21 Eliphaz admonishes Job to “submit to God” (cf. 5:8).

22:22–30 Similar to the dream that became the instrument of divine instruction in 4:12–21, Eliphaz offers God’s instructions without stipulating the instrument by which he received them, whether a dream, a prophecy, or some other means.

22:24 Ophir. Location unknown; a source of fine gold (1 Kgs 9:28).

22:25 the Almighty will be your gold. Perhaps a pun on Eliphaz’s name, which means “God is my fine gold.”

22:28–30 A righteous man has great influence with God: the stories of Moses (Num 14:13–25) and Abraham (Gen 18:21–33) bear this out, and Ezek 14:14, 20 (which names Job) affirms it.

23:1—24:25 Job’s Response to Eliphaz. Job still wishes he knew where to find God, and he believes that if he could confront him, God would listen to him and acquit him (23:6–7). Nevertheless, God “knows the way that I take; when he has tested me, I will come forth as gold” (23:10). Job expresses his intuitive insight so far into what is going on between him and God: God is trying him in order to show the purity of his character. And indeed that is precisely the case! (1:8). This explanation for Job’s suffering may be called the probationary explanation: God is trying Job to reveal his genuine religious faith. The metaphor “I will come forth as gold” builds off Eliphaz’s assurance that if Job submits to God, God will become his gold (22:25). Slowly Job is moving away from his friends and their speeches and counter-speeches and moving closer to losing himself in his own thoughts about God and his personal dilemma; his position becomes virtually two monologues (chs. 28; 29–31) that form a capstone to the dialogue.

23:3 Eliphaz instructed Job to “return to the Almighty” (22:23); Job replies, “If only I knew where to find him.”

23:6–7 Job’s confidence in a benevolent God has been growing since he declared in ch. 9 that even if he could approach God, God would prevail against him because of his power. Job insists, “No godless person would dare come before him!” (13:16), thus anticipating this moment. Now Job is sure that if he could find God, God “would not press charges” against him. On the contrary, God could establish Job’s innocence.

23:8–12 Reminiscent of Ps 139:7–12, Job depicts his desperate search for God, in contrast to the psalmist’s desperate flight from God. Yet as in Ps 139, God always knows where Job is, and when he has tested him, Job “will come forth as gold” (v. 10), just as Eliphaz suggested (22:25). In another moment of faith, Job seems to get a glimpse into the heavenly council and God’s motive for testing him. Even though that chapter is not open to him, he has read between the lines and intuited this conclusion by the give-and-take of the dialogue, by insisting on his innocence, and by his growing spiritual insight.

23:10–11 With uncanny insight, Job momentarily expresses that God knows his way, that he is being tested for his faith, and that in the end he “will come forth as gold.” It is ironic that if Job had at any point succumbed to the friends’ insistence that he plead guilty, he would have, by that sentiment alone, proved God wrong.

24:1 times for judgment. Job wonders why God does not have such times, and the reader, by dramatic irony, knows that he does (1:6; 2:1).

24:2–12 Job again “seizes the enemy’s sword” and cites violations of social ethics that Eliphaz had accused him of (22:6–9), insisting that God has not charged the wrongdoers (v. 12c).

![]()

![]()

24:3 widow’s ox. The means of her livelihood (see 22:6, 9).

24:6 Perhaps suggests that the owner of the field had not left the unharvested grain for the poor as the law required (Deut 24:19–22) but instead required them to glean in the fields of strangers.

24:7 Perhaps alludes to taking the widow’s garment in pledge (Deut 24:17).

24:13–17 Job indicts those who violate the sixth, seventh, and eighth commandments (Exod 20:13–15), preferring to do their deeds in darkness.

24:18-20, 22–24 It sounds like Job is rehearsing the position of his friends, although he admitted in ch. 21 that the wicked sometimes meet an unhappy end. To clarify, however, some translations prefix “But you say” to each statement.

24:25 Job challenges the friends to prove him wrong!

25:1–6 Second Exchange: Bildad. Only this speech (v. 2) and Zophar’s second speech (20:2) begin with a declarative sentence rather than a question containing some allusion to Job. The friends’ speeches, thankfully for Job, are getting shorter, and in this cycle Zophar does not speak at all. Bildad raises an argument that Eliphaz made (4:17–19; 15:14–16) and that Job seems to agree with (9:2): man cannot be righteous before God. Bildad insinuates that Job is about as low as a man can get (v. 6). This is complimentary of neither Job nor the human race!

25:4–6 A variation of Eliphaz’s words in 15:14–16.

26:1–14 Job’s Response to Bildad. This speech drips with sarcasm (vv. 2–4). Job describes the Creator (vv. 7–13) and his creative power much like the friends have, but Job’s conclusion is different from theirs (v. 14). When one knows God as Creator, as awesome as the Creator is, one has still only explored the “outer fringe of his works” and heard only “the whisper” of his voice (v. 14). There is yet “the thunder of his power” (v. 14) that brings real understanding. The friends have certainly not heard that, and Job himself has yet to hear it.

Regarding Zophar’s missing speech, we can assume that Zophar exhausted his arsenal of words and has nothing more he wants to say to Job. Some believe that Zophar’s speech is lost among the other speeches, perhaps 26:1–4; but taken as irony, those words fit Job’s mood and tone perfectly. The author gives us a hint of Job’s awareness that Zophar was expected to speak and did not by introducing Job’s following orations with a different formula than he has used to introduce his other speeches: “Job continued his discourse” (27:1; 29:1). The implication is that Job twice paused for Zophar to speak, and he did not, so Job continued.

27:1–23 Job’s Final Word to His Friends. Because vv. 7–23 seem more consistent with the friends’ speeches, some have suggested that they are out of place and ought to be considered part of Bildad’s short speech in ch. 25. Yet in this final speech to his friends, Job still maintains his integrity (v. 5), correlating the thesis that God has deprived him of justice (vv. 2, 5–6), and rehearses the friends’ flawed theology (vv. 13–19).

27:2 As surely as God lives. Introduces an oath, the first in the book.

27:7–10 Perhaps Job hopes that God will declare his friends (“my enemy . . . my adversary,” v. 7) wicked because of their slanderous words.

28:1–28 Job’s First Monologue: Where Wisdom Is Found. This speech is self-contained, like chs. 29–31, but it does not interrupt the flow of the poetry. Up to this point, none of the friends has comprehended wisdom. This poem is constructed around the question that constitutes the refrain: “Where can wisdom be found?” (vv. 12, 20). It divides the poem into three strophes: (1) the human search has not discovered wisdom (vv. 1–11); (2) human wealth cannot buy wisdom (vv. 13–19); (3) only God knows the way to wisdom (vv. 21–28). When the poet finally provides the classical definition of wisdom (v. 28), it comes as no surprise that Job is its representative (1:1). Yet something of the mystery of wisdom is still hidden from Job. In this way the poem points away from itself to God’s speeches.

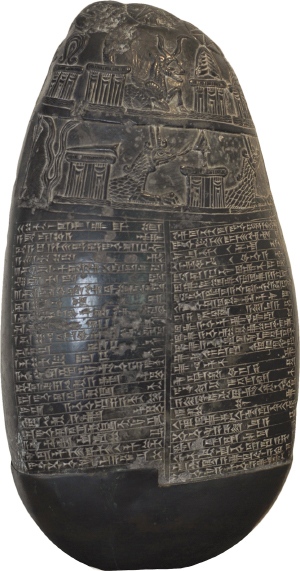

28:1–9 This description of mining is unique in the OT (cf. Deut 8:9). Silver and gold were not found in the Holy Land but were imported. There is, however, evidence of copper mining in the Negev at Timnah.

![]()

![]()

28:12, 20 This refrain asks the question the poem seeks to answer, and Job begins the answer in v. 13 with a series of denials (vv. 14–19); the question is again introduced in v. 20 to present the positive answer (vv. 23–28): only God knows the way to wisdom.

28:22 Destruction and Death. Hebrew “Abaddon and Death.” In 26:6 “Destruction” (Abaddon) is associated with the “realm of the dead”; here it is associated with death. It is probably a synonym for the netherworld.

28:28 he said. This is the only time we hear God’s voice in the dialogue. Yet it is particularly significant because it is the voice of God identifying Job, by association (1:1, 8; 2:3), as the truly wise man. Having heard this brief but essential character confirmation, Job must wait a while longer before he again hears the divine word in God’s speeches (chs. 38–41).

29:1—31:40 Job’s Second Monologue: Job’s Final Defense. God still has not appeared to or answered Job as Job had challenged God to do. At this stage, Job sums up his defense, never once addressing his friends. First, he reflects on the past, when he was a respected member of the community (ch. 29); second, he laments his present plight (ch. 30), which includes a loss of his wealth and honor; third, he climaxes the speech with a series of oaths to establish his innocence (ch. 31). One oath would have been enough, but the series reinforces Job’s belief in his innocence. He closes this speech with the challenge that God write out his indictment against him (31:35–37) and concludes with the last oath, intimating that he is not guilty of violating the created order (31:38–40). One of the important issues in the book is God’s silence. He cannot intervene because this would prove Satan’s claim. Job must receive no support from God. It is important that Elihu’s speeches separate Job’s speech from that of God, suggesting that God does not respond directly to Job’s plea.

29:2–6 Job longs for the good life when God “watched over” him (v. 2). Only the reader knows by dramatic irony how carefully God is still watching over him. Job reflects that his children and wealth were tangible tokens of God’s favor.

29:7–11 Job’s community greatly esteemed him.

29:7 gate of the city. The gathering place for friends and the place where the court convened to decide legal matters (see Ruth 4).

29:12 the poor . . . the fatherless. In keeping with the law and the Hebrew faith, Job defended the weak and helpless (vv. 12–17).

29:14 I put on righteousness as my clothing. A way to express his intimate relationship with God. This is, in different words, very close to God’s description of Job in the prologue (1:1, 8; 2:3). For similar imagery, see Ps 132:9, 16; Isa 59:17; 61:10; Rom 13:14; Eph 4:24; 6:14–17.

29:18–20 Job thought his life would turn out totally different.

29:21–25 Repeats the thought of vv. 7–10 (his compatriots’ esteem for him) and transitions to words about his friends’ contempt for him in ch. 30.

30:1–15 In sharp contrast to the respect he once enjoyed in the community, Job informs the reader that a group of scavengers, human in form but animal in behavior (vv. 6–7) and “younger” (v. 1) than he, mock him in word and song. They make a sport of it, and their fathers are no better than they are. Perhaps they are motivated by the three friends and their disrespect for Job, which is generally known in the community (the debate is most likely public).

30:1 In the ancient Near East, dogs were wild scavengers. Sheep dogs were more domesticated but not much more socially respectable.

30:16–23 Job laments his present suffering.

30:24–31 Job again reviews how he compassionately treated the poor (29:12–17), quite the opposite of how these human scavengers treat him (vv. 1–15).

30:30 Another description of his deteriorating physical condition (vv. 17, 27, 28; 7:5; 16:16; 18:4; 33:19–22).

![]()

![]()

31:1–4 Because Job believes that God punishes wrong, he has lived by a moral code, knowing that God is aware of his actions.

31:1 Like the tenth commandment (Exod 20:17), this moral principle regulates Job’s thought life.

31:5–40 This series of oaths is a capstone to the dialogue, sealing Job’s belief in his innocence.

31:9–12 Job takes an oath that he has not committed adultery (Exod 20:14).

31:13–15 Job swears that he has not mistreated his servants, whom he considers like himself: God’s creations.

31:16–23 Job takes an oath that he has cared for the widow, orphan, and needy.

31:24–28 Job takes an oath that he has not worshiped any other gods, including the god of wealth (Exod 20:3–6).

31:29–32 Job takes an oath that he has not “gloated over” (v. 29) his enemies’ downfall or failed to offer hospitality to strangers.

31:33–34 Job takes an oath that he has not been hypocritical.

31:35–37 Job breaks into his string of oaths (note the parentheses) with a wish that there was “someone to hear” him (v. 35) and that he could make his case before such a person (16:19; 23:3–7, 10). This is Job’s signature as he submits his indictment to God.

31:38–40a Job takes a final oath: he has not abused the soil or those who cultivate it—perhaps an allusion to the basic curse on the soil (Gen 3:18; 4:12)—and has not violated the created order.

31:40b A formula indicating the end of the dialogue. Cf. Ps 72:20.

32:1—37:24 The Elihu Speeches. Only here is the reader informed that Elihu was present during the dialogue. After his four speeches (cf. three for each of the friends except Zophar), we do not hear about him again, not even in the epilogue, which mentions all three men as the object of Job’s prayer (42:7–9). The tone of Elihu’s speeches is set by multiple references that he was angry (32:1–5). On a more logical note, he explains that he is younger than the three friends, and in deference to their age, he did not speak (32:6). But now that the dialogue is obviously ended, Elihu feels the compulsion to speak because Job “was righteous in his own eyes” (32:1) and justified himself rather than God and because the three friends “found no way to refute Job” (32:3; see 32:1–5). He claims to understand Job’s arguments, and several times he repeats or summarizes Job’s words (33:8–11, 13; 34:5–6; 35:2–3). Twice he challenges Job to answer his arguments (33:32; 34:33), but Job never dignifies Elihu’s speeches with a reply. Some view the Elihu speeches as comic relief; i.e., Job was ready for God to speak (31:35), but Elihu steps in to claim he has the answer, only to rehash the friends’ arguments and add little new to the debate. He is the only one of the participants to use Job’s name, perhaps suggesting his youthful, yet artless, demeanor. Though his claims fall short, he believes he has contributed to the argument of the dialogue. Indeed, his contribution that suffering is sometimes disciplinary is of significance to the larger discussion regarding suffering: God uses suffering to discipline and correct a wayward individual (33:14–30; 36:8–11, 15–17; 37:13); but Eliphaz had already suggested this argument in his first speech (5:17–18). Yet Elihu, unlike the reader, had no notion of the reason for Job’s suffering. The prologue spells out that Job’s suffering was to show what an exemplary man Job was, that he served God with no ulterior motives, phrased in Satan’s famous question, “Does Job fear God for nothing?” (1:9).

32:1—33:33 Elihu’s First Speech. Elihu explains to the friends (32:6–22) and to Job (33:1–7) how he is going to intervene. He recalls the three friends’ failed efforts (32:12, 14–16) and Job’s arguments (33:9–11), and further describes Job’s physical distress and emaciated body (33:19–33).

32:2 Elihu. Means “he is my God.” He is given a full patronymic of father, tribe, and clan, thus reinforcing his pretentious claim of importance. His ethnic origin is uncertain.

32:3 Job . . . condemned him. See NIV text note.

32:6 Elihu is speaking to the three friends.

32:8 Elihu insists (see v. 18 and note) that the “breath of the Almighty,” not age, gives wisdom (“understanding”). For him, true wisdom is an understanding of Job’s suffering and what lies behind it. More practically, wisdom is to provide a solution to Job’s problem.

32:14 I will not answer him with your arguments. A jab at the three friends.

32:15 words have failed them. Along with v. 14, this gives the reader a window into Elihu’s uncomplimentary estimate of the three friends.

32:16 they stand there with no reply. Implies that the friends have miserably failed to answer Job, augmenting his negative view of their efforts.

32:18 the spirit within me compels me. Elihu claims that God is the inspiration of his compulsion to speak (v. 8).

33:1 Elihu addresses Job using his personal name, unlike the friends in the dialogue, which may imply an inappropriate familiarity edging on disrespect.

33:5 Answer me then, if you can. Job had concluded the dialogue by expressing his desire for someone to answer him (31:35–37)—but Job had God in mind, not Elihu.

33:9–11 Elihu quotes Job’s words (13:24, 27).

33:15 Like Eliphaz (4:12–21), Elihu claims that God speaks in dreams and visions.

33:19–27 The person described in vv. 19–22 is most likely Job. Elihu holds out hope of deliverance for Job if Job will admit his sin (v. 27; cf. the friends’ view in 4:6–8; 10:6).

33:23 messenger. Comparable to “someone to mediate between us” (9:33), but in this case it is someone to explain how Job can be upright.

33:31 Elihu again addresses Job by his personal name (see v. 1 and note).

33:33 Elihu has a bloated sense of his own wisdom and a blighted sense of Job’s.

34:1–37 Elihu’s Second Speech. Elihu addresses the friends and refutes Job’s claim to innocence (vv. 1–15); he then addresses Job, insisting that divine governance and divine justice are inseparable (vv. 16–30), and calls Job to repentance (vv. 31–33).

34:2 Address to the friends, perhaps sarcastically.

34:3 Evidently a proverb (cf. 12:11). In view of other quotations of Job’s words (33:9–11), Elihu had listened well.

34:5 Cites Job’s claim of innocence in 27:2a.

34:7–9 Another description of Job (cf. Eliphaz’s description of Job in 22:5–9). It is totally the opposite of who Job is, according to the prologue. Although Elihu boasted that he would not answer Job with the friends’ arguments (32:14), he is already violating his pledge.

34:10–12 Addressing the friends rather than Job, Elihu’s defense of God’s justice implies he thought that the friends had misrepresented divine justice or that they had let Job get away with such a misrepresentation: “Far be it from God to do evil” (v. 10). The principle is retributive justice: “He repays everyone for what they have done” (v. 11). Verse 12 echoes Bildad’s question in 8:3.

34:13 Who appointed him over the earth? God rules the earth and is answerable to no one since he is self-appointed. As a counter argument, Job has argued that God rules the earth and is therefore responsible for what happens to human beings (9:12, 24).

34:16 Elihu turns from the friends to address Job.

34:17 God must be just in order to govern; therefore, since he governs the world, no one can accuse him of injustice.

34:21–25 Job asked in 24:1 why the Almighty does not keep times of judgment when his subjects can present their claims to him. Elihu argues that God does not need to do so because he sees everything. The reader knows that God does judge.

34:31–32 Elihu, as in 33:27, indirectly proposes that Job confess his sin, which would be a confession of guilt. However, the dialogue is built in part upon Job’s claim of innocence—a claim the prologue supports. To confess his sin would be a falsehood on Job’s part.