The book of Proverbs is an anthology of seven collections attributed to Solomon and other wise individuals (see Outline). The number seven symbolizes divine perfection. The initial collection plays a significant role in the book, for it illuminates the value of wisdom and identifies the prerequisite for acquiring the wisdom presented within the remainder of the book.

Authors

As is true of all Scripture, the book of Proverbs was authored by human authors and the divine author (2 Tim 3:16). Regarding its human authors, the superscript (1:1) identifies Solomon (970–931 BC) as the book’s principal author. The internal evidence of the book supports this identification. Collection I (1:8—9:18) is associated with Solomon, as is Collection II (10:1—22:16), and Hezekiah’s scribes attribute Collection V (25:1—29:27) to Solomon as well (25:1). Probably Solomon was responsible for adapting the sayings of other sages in Collections III (22:17—24:22) and IV (24:23–34). Collection VI is attributed to Agur (30:1–33); Collection VII, to King Lemuel (31:1–31). The titles within the book indicate that several authors produced the material over an extended period of time, and they imply that an anonymous sage edited the whole collection.

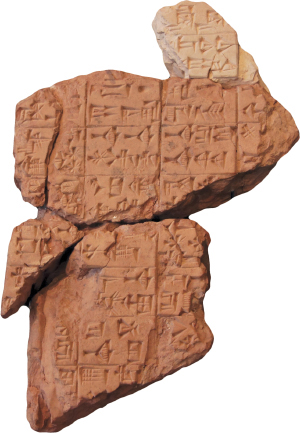

There are good reasons to accept these biblical ascriptions of authorship at face value. Biblical references to Solomon’s wisdom are numerous (1 Kgs 3:5–14; 4:29–34; 5:7, 12; 10:1–9, 23–24; 11:41; 2 Chr 1:7–12; 9:1–8, 22–23). Moreover, there are striking similarities in structure and content to comparable wisdom literature from Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, straddling the biblical world from the third millennium BC to Greco-Roman times. The forms and motifs of Collection I are similar to Egyptian “instructions” that date as early as 2500 BC; the titles of Collections I (1:1) and II (10:1) resemble the titles of Egyptian collections at the time of Solomon. The first ten sayings of Collection III, called “Thirty Sayings of the Wise,” share similarities with the Egyptian “Thirty Sayings of Amenemope.” Also, the collections attributed to Solomon teem with linguistic characteristics of his time. By contrast, the Aramaisms in Collection VII give scholars reason to think that the material was composed in the postexilic period, i.e., during the period of the book’s final editing. While the ascriptions to Solomon do not demand that he wrote every proverb within the collections that bear his name, they suggest that he played an important role in the composition and collection of the materials in the book. If one asks how Solomon could be so wise and die a fool, his own proverb provides the answer: “Stop listening to instruction, my son, and you will stray from the words of knowledge” (19:27). Being wise one day is no guarantee of being wise the next.

Regarding the divine author, Israel’s canonical historian informs us that God gave Solomon wisdom “greater than the wisdom of all the people of the East, and greater than all the wisdom of Egypt” (1 Kgs 4:30). In addition, the parental voice within Prov 1–9 asserts that the Lord gave the wisdom (i.e., the “words” [2:1]) found in the book: “For the LORD gives wisdom; from his mouth come knowledge and understanding” (2:6). Even the sayings of Agur son of Jakeh and of King Lemuel are identified as “inspired utterance[s]” (30:1; 31:1). When Solomon’s proverbs and the sayings of the wise are internalized into the heart by memory and faith, the wisdom of God himself enters hearts of flesh (2:10).

Audience

In light of the preamble (1:1–7), the original audience consisted of two groups of people: (1) youths (1:4) and (2) the wise (1:5). The youths are characterized as simple, uncommitted (see note on 1:4), and gullible individuals on the brink of adulthood. The sage, in the guise of Lady Wisdom, challenges them to repent and choose wisdom, for they are headed for eternal death. She addresses them at the gate of the city, pleading with them to repent and embrace wisdom before they meet the temptations within the city. The book seeks to illuminate the value of wisdom and persuade these youths to choose the path of life. The second group addressed are those characterized as wise, i.e., individuals who cherish and choose wisdom but recognize that the search for wisdom is a lifelong process. In this respect, they are teachable, and the book seeks to develop their wisdom by sharpening the mind, softening the heart, and shaping the character of these wise and righteous people.

While the courtly setting of the parallel ancient Near Eastern texts and the royal texture of the collections (cf. 8:15; 16:12; 23:1; 27:23–24; 31:4) suggest the book was originally written for budding royal officials, the material has been democratized for all of Israel’s youth, especially young men of marriageable age (1:1–4). This explains the male-centered nature of much of the material in chs. 1–9, which focuses on illicit sexual relations with females. Nonetheless, this male-centered focus does not mean that the book’s instruction excludes women. To the contrary, virtues and vices presented in the material are relevant to both males and females. In this case, the “son” within chs. 1–9 may be taken as a child, a youth preparing to exit the household and enter the community as an independent adult.

The domestic, or familial, setting of the materials within Proverbs is intimated by the father-son discourses in chs. 1–9 as well as by the inclusion of the mother in the instructions (1:8; 6:20; 31:1). While the father-son idiom could refer to a teacher-pupil relationship, the inclusion of the mother, as well as the absence of any reference to schools in Israel during biblical times, makes this suggestion less than convincing.

Even though the material in the book is cast in a specific social and dialogical context (i.e., parents to a child within the home), as part of holy Scripture, the book of Proverbs now addresses the church. Christ’s apostles cite the book in various ways about 60 times. Peter uses 26:11 as a proverb with reference to false teachers (2 Pet 2:22). Paul uses 25:21–22 to teach about feeding your enemies (Rom 12:20). And the writer of Hebrews uses 3:11–12 to convince the audience that hardships are a manifestation of God’s correction, care, and commitment rather than a sign of his indifference (Heb 12:5–6). Beyond these explicit quotations within the NT, the book of Proverbs plays a significant role in the church’s understanding of ethics. On the whole, the book distills and reapplies the ethical principles presented in Israel’s covenant tradition (e.g., Exod 20–23; Lev 17–25; Deut 5–26) and provides the foundation for Jesus’ and the NT writers’ conception of kingdom ethics. In this sense, the book describes not only how people might live in accordance with the wise life but also how people might embody the virtues that mark the kingdom.

Character Types

Within the book’s domestic setting, the reader encounters a variety of different characters, each of which plays a significant rhetorical and educational role within the book. As noted above, the preamble identifies two prominent characters within the anthology: the wise (1:5) and the simple (or youth, 1:4). While “the wise in heart accept commands” and “store up knowledge” (10:8, 14; cf. 15:31), the simple remain open, committed to nothing. The simple person loves being uncommitted and is gullible and easily misled (14:15). This disposition explains the father’s and Lady Wisdom’s interest in the simple (1:20–26; 7:6–27; 8:4–5). The simple encounter various voices and characters vying for their allegiance within chs. 1–9 (sinful people, the wicked, evildoers, and the adulterous woman, who is presented in the guise of the woman Folly). The father and Lady Wisdom attempt to expose these bad character types—the futility of their promises and the consequences associated with following their path—and illuminate the value of wisdom. The father instructs his son about the danger of being simple (7:1–23), and Lady Wisdom, who represents the book’s wisdom, motivates the simple to commit their lives to the path of wisdom (1:33).

While the simple love being open to any opinion and committed to none (1:22), fools are fixed in the correctness of their own opinions—opinions that fly in the face of the values that restore humanity to the moral order that God ordained and Proverbs reveals (12:15; 15:5, 20). Their morally deficient character prompts their irrational behavior. They are simpletons because they are deaf to wisdom. From their distorted moral vision, of which they are certain, they delight in twisting values that benefit the community.

Worse than fools are mockers, those who are hardened apostates. They hate the wise and mock their wisdom (9:7–8); they are beyond Wisdom’s call. Their spiritual problem is rooted in their boundless pride (21:24).

Also worse than fools are sluggards (26:13–16; cf. 6:6–11; 10:26; 13:4; 15:19; 19:24; 20:4; 21:25; 22:13; 24:30–34). Their unreliable and procrastinating natures make them constant sources of irritation to all those who need to do business with them (10:26), and they lose their families’ heritage (24:30–34).

Nonetheless, despite these gradations of character types, it is important to recognize that Proverbs employs a variety of terms to describe the multifaceted character of the wise (“upright” [2:6–7], “righteous” [9:9], “generous” [11:25], “diligent” [12:24]) and the fool (“wicked” [10:23], “lazy” [26:15], “stingy” [28:22]). These descriptive terms do not denote different groups of people. Rather they illuminate the social, moral, and intellectual traits of the same type of person. In this respect, not only are the wise marked by an intellectual and practical ability to live in accordance with God’s design, but they also embody righteousness, integrity, diligence, and generosity. In the same way, fools are not simply senseless dolts; they are also wicked, brash, and greedy. While Proverbs employs a variety of terms to describe diverse character types, on the whole, the book divides humanity into three basic categories: the wise/righteous, the simple, and the fool/wicked. Through these categories and the book’s graphic portrayal of various character types, Proverbs attempts to shape the character and worldview of its readers by providing them with a vision of life rooted in the fear of the Lord and characterized by wisdom, which is inseparable from virtue. In this respect, the portrayals of these character types are not merely descriptive; they are also transformative. They form our feelings, sharpen our thinking, pinpoint our vices, cultivate virtue, and offer us a wise perspective on life.

Literary Features

As an anthology of wisdom, Proverbs contains a variety of different materials, ranging from extended parental instructions (1:8–19) to autobiographical reflections (24:30–34) to alphabetic acrostics (31:10–31) to short, pithy sayings (22:17—24:22). While the literary frame of the book contains longer didactic discourses (1:1—9:18; 30:1–33; 31:1–9, 10–31), scholarly opinion differs regarding whether the central collections are a random smorgasbord of individual proverbs or whether they are connected with one another in various ways. Despite the literary or generic variety within the book, however, four literary features characterize the diverse materials in Proverbs.

1. Hebrew Poetry. Like all poetry, Hebrew poetry is marked by terseness, vivid imagery, and figures of speech. Unlike English poetry, it is characterized by parallel lines in which the second line either (1) emphatically restates the first line (e.g., “Let someone else praise you, and not your own mouth; an outsider, and not your own lips” [27:2]), (2) expands the first line (e.g., “Honor the LORD with your wealth, with the firstfruits of all your crops” [3:9]), or (3) presents a contrast to the first line (e.g., “A wise son brings joy to his father, but a foolish son brings grief to his mother” [10:1]).

2. Wisdom Literature. The various materials within the book are an integral component of the international tradition of wisdom literature. In contrast to the materials in the Pentateuch and the Prophets, Israel’s wisdom literature is characterized by a remarkable secularity; it focuses on the world of nature (30:18–19) as well as human behavior (24:30–34) and experience (4:1–9). This focus does not mean that Israel’s wisdom literature is a brand of natural theology, for Proverbs refers to God by his covenantal, personal name (“LORD”) and observes the creation through the lens of Israel’s covenant values. Indeed, all of the observations on nature, as well as human experience and behavior within the book, are passed through the filter of faith (i.e., “the fear of the LORD” [1:7; 2:5; 9:10; etc.]). From this theological perspective, Israel’s wisdom literature teaches covenant values but makes no mention of Israel’s historic covenants. That is, it complements Israel’s covenant tradition by reflecting upon and recontextualizing its ethical and theological worldview from a distinct frame of reference (see Introduction: Theme).

3. Wise Sayings. The sayings within the central collections of the book are quite distinct. As proverbs, they represent short, pithy sayings that communicate a traditional or popular truth, such as “A stitch in time saves nine.” But unlike this English proverb, the sayings of Proverbs have currency among the people of God, not the world in general, because they are based on faith in Israel’s covenant-keeping God. “Do not be wise in your own eyes; fear the LORD and shun evil” (3:7) runs counter to the popular sayings of unbelievers such as “Believe in yourself” and “The Lord helps those who help themselves.” The book’s sound bites function as exemplars by which the people of God are to compare their own behavior or thinking.

4. Contextual Truth. It is important to note that proverbs express a truth, but only a limited truth that other proverbs must nuance or qualify. For example, “The LORD does not let the righteous go hungry, but he thwarts the craving of the wicked” (10:3) seems to contradict the experiences of many believers and of the Lord Jesus Christ, who hungered for 40 days in the wilderness (Matt 4:1–2). The preceding proverb, however, safeguards that saying from misunderstanding: “Ill-gotten treasures have no lasting value, but righteousness delivers from death” (10:2). In other words, the wicked have treasures for a while, but in the end they will lose all, whereas the righteous in the end will be delivered even from death. This proverb pair also shows that Proverbs looks at the end of a matter. The proverb “Though the righteous fall seven times, they rise again, but the wicked stumble when calamity strikes” (24:16) grants that the righteous may be completely knocked down, presumably even by death, but they will rise, unlike the final catastrophic end of the wicked. In addition, one should not read “Start children off on the way they should go, and even when they are old they will not turn from it” (22:6) to mean that a child is a programmed robot. This proverb teaches that parental training has its effect throughout a person’s life, but the proverb must be nuanced by other proverbs and sayings such as “The eye that mocks a father, that scorns an aged mother, will be pecked out by the ravens of the valley, will be eaten by the vultures” (30:17). Each proverb presents a truth, but this truth must be discovered within the context of the entire collection of sayings and contextualized or applied to appropriate circumstances (see 16:10–15; 26:4–5; 28:15). The same is true of English proverbs. The sayings “Don’t cry over spilled milk,” “Many hands make light work,” and “Too many cooks spoil the broth” are true. But one has to discern which proverb is appropriate within a particular situation. In this case, a proverb should not be read only as an independent, isolated saying that communicates a truth; it should also be read in its immediate and broad literary context as well as in conversation with other proverbs that reflect on the truth or topic treated by the saying.

Theme

In essence, Proverbs seeks to teach wisdom (1:1–2). By definition, wisdom means “masterful understanding, skill.” While the term elsewhere describes those with physical, moral, technical, or intellectual skills, in Proverbs it refers to the skill of godly living with respect to God and people.

In this respect, wisdom is distinct from knowledge but cannot be had apart from it. The Wright brothers flew the first airplane because they had first figured out the fundamental laws of aerodynamics; a mechanic’s skill depends on his knowledge of the motor. The wise have social skill because they know personally, not merely about, the proverbs and sayings of this book. This knowledge is gained in the fear of the Lord, which entails humbly accepting the book’s instruction; disciples embrace the inspired sages’ knowledge and wisdom because they trust and fear the Lord, who inspired these sayings and upholds them (1:7). As cement without water cannot produce mortar, so the proverb without faith that submits to the Lord’s Word cannot produce wisdom. The wise have faith not in the proverbs per se but in the Lord who upholds the truth in the proverbs. “Trust in the LORD with all your heart” (3:5) means to trust the one who has inspired this book.

Out of his grace, God gave the Mosaic law and the Prophets to his people in order to reveal his will after the fall into original sin in Adam. But the book of Proverbs takes up those matters that are too fine to be caught in the mesh of the law and too small to be hit by the broadsides of the Prophets. The proverbs concern themselves with qualities such as honesty, integrity, diligence, kindness, generosity, readiness to forgive, truthfulness, patience, humility, cheerfulness, loyalty, temperance, and self-control. Anger is to be held in check, violence and quarrelsomeness shunned, gossip avoided, arrogance repudiated. Drunkenness, gluttony, envy, and greed are also to be renounced. The poor are not to be exploited, the courts are not to be unjustly manipulated, legitimate authorities are to be honored. Parents are responsible to care for the proper instruction and discipline of their children, and children are to duly honor their parents and bring no disgrace on them. To embrace these values brings God’s rule to earth; they are the way of life; to defy them is the way of death.

The dominant metaphor for the moral life in Proverbs is the “way.” The metaphor portrays life as a journey (cf. Paul’s use of peripateō, the Greek word for “walk,” in Rom 6:4 [“live”]; 8:4 [“live]; 13:13 [“behave”]; 2 Cor 12:18 [“walk”]; Eph 2:2 [“live”]; 2:10 [“do”]; 5:2 [“walk”]; 5:15 [“live”]). By virtue of its use with the lifestyles of the wise and the fool, as well as those of the righteous and the wicked, the metaphor refers to a person’s character, social context, conduct, and, above all, the consequences of these characteristics. The wise always keep in mind the consequences of their actions: either life or death; there is no third way.

Lady Wisdom

The wisdom that this book gives (see 1:1–2) is personified as a woman in chs. 1–9 (1:20–33; 8:1–36; 9:1–6). This literary device is significant in at least three respects: (1) Personification creates a framework through which to understand Wisdom’s multifaceted character. It provides a means by which we may understand the diverse images of prophet, teacher, counselor, lover, daughter, mother, and host. (2) Personification transforms abstract knowledge into an attractive form. (3) Personification allows wisdom (as Lady Wisdom) to represent the antithesis of both the adulterous woman (5:1–6; 6:20–35; 7:1–27) and the woman Folly (9:13–18). Lady Wisdom is the object of desire, the one who understands the fundamental patterns within the universe (see 8:22–31 and notes), and the one who can align her devotees’ lives in step with those patterns to live in harmony with God’s creative activity. Wisdom’s female persona also plays an important role in the book as a whole, serving as the metaphoric counterpart to the woman that 31:10–31 describes.

While Lady Wisdom is a distinct figure within the prologue, it is important to recognize that she makes her appeals to the simple youths (see note on 1:4), who are represented as not living in their parents’ home, to accept the book’s wisdom (1:20–33; 8:1–36; 9:1–6); the parents, presumably in the home, exhort the covenant child to accept its wisdom. Striking parallels link Lady Wisdom’s addresses with those of the parents. Her admonitions and her motivations in 8:32–36 match those of the parents elsewhere (e.g., 3:3–4; 4:20–22). And in light of the introductions to Lady Wisdom’s formal speeches, it appears that the father serves as Lady Wisdom’s voice. Together with the parents, Lady Wisdom provides readers with an antidote for seductive speech. That is, she interprets the sly rhetoric and deceptive promises of the other characters in the prologue to move readers to embrace her and the way of life.

The Wisdom of Proverbs and Jesus Christ

The poetic description of Lady Wisdom in 8:22–31 contributes to an understanding of Jesus’ nature and identity. Similar to the way John 1:1–5 describes Jesus, Prov 8:22–29 affirms that Wisdom existed before the creation of any element within the cosmos. In Wisdom’s address to the simple in 1:20–33, she humbles herself, calls sinners to repentance, and serves as a mediator between the Lord and humanity in much the same way that Jesus humbled himself, called sinners to himself, and serves as the only Mediator between God and humanity (1 Tim 2:5; Heb 9:11–28). As the truly wise king, one greater than Solomon, Jesus exemplifies God’s wisdom. But unlike Jesus Christ, Lady Wisdom is represented as being born (8:24), and so she is not eternal. She is also represented as an instrument of creation (3:18–19) and as present at the creation (8:30), but she is never represented as the Creator. The NT never identifies Lady Wisdom with Jesus Christ, who is the Creator (John 1:1–5; Col 1:16–20). Rather the NT uses wisdom as a theological category to describe Jesus’ identity, deity, and redemptive work.

Accordingly, the trajectory of Proverbs’ words of wisdom terminates in Jesus Christ and in his church. Jesus is the eternal Word made flesh (John 1:1–18); in him “are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col 2:3). His church participates in this more-than-fulfillment by abiding in him (John 15:1–6). The church is being conformed to his likeness by faith in him (1 Cor 1:24, 30; Col 2:2–3).

The culmination of Proverbs’ wisdom being in Jesus is apparent through the various ways in which the book’s ethical advice and description of the Lord’s actions are displayed in Christ. This is not surprising because Jesus is God and his wisdom is superior to the wisdom of Solomon (Matt 12:42). Whereas Proverbs teaches its disciples to wait for God to repay the wrongdoer (24:12), Jesus declares that he will repay them (Matt 25:41–46). Whereas Proverbs depends on God to discipline those he loves (3:11–12), Jesus affirms that he disciplines those he loves (Rev 3:19). Whereas Proverbs teaches that God will reward those who share with the poor (14:21), Jesus identifies himself with the poor and as the one who rewards those who sacrifice for the poor (Matt 25:31–46). While no human has ascended into heaven (Prov 30:4), Christ both descended from heaven and ascended into it (John 3:13). While Proverbs calls on its disciples to write its teachings on their hearts (3:3), Christ sends his Spirit to write God’s word on believers’ hearts (2 Cor 3:3). And whereas Proverbs calls on its disciples to feed their enemies (25:21), Christ died for his enemies (Rom 5:8).

The NT manifests the ethical and theological significance of the instructions within Proverbs through the teaching of Jesus. And the activities of God within Proverbs are connected with Jesus in the NT. No wonder Paul describes Jesus as “the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24), the one through whom the believer receives wisdom (Eph 1:7–10).

Outline

I. Preamble and Prologue (1:1—9:18)

A. Preamble: Purpose and Theme (1:1–7)

B. Prologue: Exhortations to Embrace Wisdom (1:8—9:18)

1. Warning Against the Invitation of Sinful Men (1:8–19)

2. Wisdom’s Rebuke (1:20–33)

3. Moral Benefits of Wisdom (2:1–22)

4. Wisdom Bestows Well-Being (3:1–35)

a. The Lord’s Promises and the Son’s Obligations (3:1–12)

b. The Value of Wisdom (3:13–35)

5. Get the Family Heritage (4:1–9)

6. Stay Off the Wrong Way (4:10–19)

7. Don’t Swerve From the Right Way (4:20–27)

8. Warning Against Adultery (5:1–23)

9. Warnings Against Folly (6:1–19)

10. Warning Against Adultery (6:20–35)

11. Warning Against the Adulterous Woman (7:1–27)

12. Wisdom’s Call (8:1–36)

13. Invitations of Wisdom and Folly (9:1–18)

II. Proverbs of Solomon (10:1—22:16)

III. Thirty Sayings of the Wise (22:17—24:22)

IV. Further Sayings of the Wise (24:23–34)

V. More Proverbs of Solomon (25:1—29:27)

VI. Sayings of Agur (30:1–33)

VII. Sayings of King Lemuel’s Mother (31:1–31)

A. Sayings of King Lemuel (31:1–9)

B. Epilogue: The Wife of Noble Character (31:10–31)

![]()

![]()

![]()