The book of Daniel contains two parts. Chs. 1–6 present accounts of Daniel and his three friends in a foreign court; chs. 7–12 contain four apocalyptic visions. Each account and each vision expresses the same important message: in spite of present circumstances that make it appear as if evil is winning the day, God is in control and will have the final victory. This message has brought comfort to God’s people throughout history and up to the present day.

Author

Until the twentieth century, Christian and Jewish scholars agreed that Daniel, the book’s main protagonist, wrote the book. Daniel speaks in the first person in the four visions of the second half of the book (7:2, 4, 6, 28; 8:1, 15; 9:2; 10:2), and it is Daniel who is told to “seal the words of the scroll” (12:4). At a minimum, the internal evidence of the book claims that Daniel received the visions. However, since the first six chapters of the book are stories about Daniel and since the visions themselves often have a third-person introduction (7:1; 10:1), this allows for but does not require the possibility that a later editor could have written the final form of the book. Though the NT often cites the book of Daniel, only Matt 24:15–16 (speaking of the “abomination that causes desolation” [Dan 9:27; 11:31; 12:11]) names Daniel as the author. The real controversy concerning authorship concerns the visions that the book connects to Daniel’s personal experience (see Date).

Date

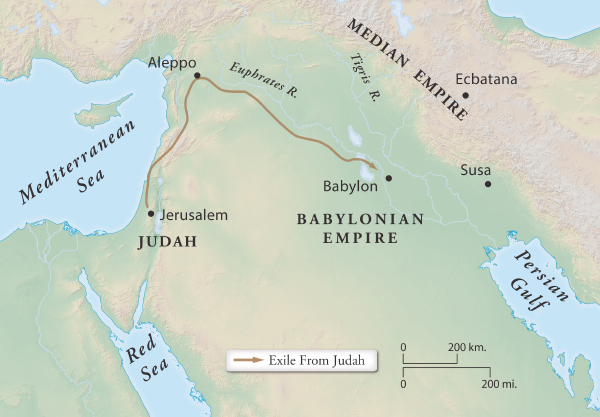

The stories and the visions of Daniel are firmly set in the context of events that occur between 605 (see 1:1 and note) and 537/536 BC (see 10:1 and note). Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar, Cyrus, and Jehoiakim are well-known figures from this time period. This period of time is crucial in the history of God’s people, stretching from the beginning of Babylonian encroachment into Judah and covering the time of the destruction of Jerusalem (though not mentioned in the book) and the end of the exile. The book has its foundation in events and visions that occur in the sixth century BC.

Some, however, claim that a sixth-century dating for the book is impossible due to the contents of the visions, particularly that of the vision in ch. 11. As the notes on ch. 11 show, it contains prophecies connected to the Seleucid (king of the north) and Ptolemaic (king of the south) kingdoms of the late fourth to mid-second centuries BC. To some, precisely predicting these future events is simply impossible and this points to a date of writing in the second century BC. Furthermore, these people point to 11:36–45 as an example of a failed prophecy of the death of the climactic king of the south (Antiochus IV) thus being an indication that the book was written just before his death (ca. 164 BC). Not all who opt for this late date of the writing of the book do so because they reject the idea of true prophecy, but many do. (For more on this issue, see note on 11:36–45.) The discovery of a second-century BC partial copy of Dan 11 among the Dead Sea Scrolls (4QDanc) lends strong support to those who argue that this passage was composed much earlier than the time the predictions describe. The notes in this study Bible assume that Daniel received these visions from God in the sixth century BC.

Place of Composition

While God may have used an editor to bring the book of Daniel to its inspired final form, the book originates with Daniel, who lived in the royal court in Babylon.

Particular Challenges

The biggest challenge, addressed above (see Date) and in the notes (see note on 11:36–45), concerns the charge that the supposed failed prophecy in 11:36–45 exposes that the precise predictions in 11:5–35 are really prophecies after the fact. Others have used two additional issues to challenge the book’s historical reliability and to support the view that the book was written in the second century BC with a murky knowledge of earlier events.

1. Dan 1:1 claims that Nebuchadnezzar besieged Jerusalem during the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim, king of Judah; but Jer 25:1 states that Nebuchadnezzar’s first year was Jehoiakim’s fourth, and Jer 36:9 says that the Babylonians did not come to Jerusalem until the fifth year of Jehoiakim. To some, the Babylonian Chronicle supports Jeremiah’s chronology. However, there were two systems of dating in place at this time. Jeremiah used the Judahite method that reckons the first year of a king’s reign as his first year, while Daniel used the Babylonian system, which counts the first year as his “accession year.”

2. Mystery surrounds the figure of Darius the Mede (5:31; 9:1), who became king when Belshazzar was executed (5:30) and was the one who was forced to send Daniel to the lions’ den (ch. 6). Darius is not known in the extrabiblical sources of the day, and one would expect the book to name the “king of Babylon” as Cyrus the Persian (who defeated Babylon), not Darius the Mede. While certainty on this matter is not possible at this time, solutions exist. Perhaps, for instance, Darius is to be identified as a man named Gubaru, who is known from Babylonian texts as the governor of Babylon. More likely is the idea that Darius is a second name for none other than Cyrus. Historical sources attest to the practice of a king ruling two nations under two different names (see note on 6:28).

Occasion and Purpose

The book was written to encourage those living during times of oppression and persecution. Its stories and visions show that it is possible not only to survive but to thrive as a faithful follower of God under the most difficult conditions. While not every Christian today faces the severe persecution that Daniel and his friends encountered, they do live in a culture that is toxic or hostile to the faith, and the book’s reminder that God is in control and will win the final victory provides confidence for living in the present and hope to face the future. The book does not intend to give information that would allow readers to predict the time period when Jesus will return at the end of the age.

Genre and Structure

The book of Daniel has two major parts. Chs. 1–6 contain court narratives (stories about Daniel and his three friends living in a foreign court); chs. 7–12 present four visions that contain apocalyptic prophecies. Interestingly, the book is written in two different languages, though the Hebrew (1:1—2:3; chs. 8–12) and Aramaic (2:4—7:28) do not coincide with the genre division.

The court narratives focus on the interaction between Daniel and/or his three friends and members of the Babylonian or Persian court. Ch. 1 narrates how the four men come to Babylon and how they preserve their faith as they are forced to prepare for service in the Babylonian royal court. Chs. 2, 4, and 5 tell stories of court contests. In ch. 5, for example, when the king has a problem of interpretation, his Babylonian wise men cannot provide a solution. Where they fail, Daniel succeeds, thus demonstrating the superiority of Daniel’s God, which leads to Daniel’s promotion. Chs. 3 and 6 contain stories of court conflicts. In ch. 3, e.g., the three friends are set up by their court rivals and accused of not bowing down to Nebuchadnezzar’s golden statue. God delivers them from the fiery furnace, and those who challenged them are thrown into it. The three friends are then promoted.

The four visions in chs. 7–12 are apocalyptic in nature. Apocalyptic and prophetic books share many features but differ in key areas. While prophetic texts like Jeremiah focus on the near future, Daniel looks beyond the near future to events of the end times. While God commissions a prophet to preach to the people to elicit repentance, Daniel receives visions that intend to comfort the people of God who suffer oppression. Daniel’s apocalytic texts share intense imagery that often baffles modern readers, for the imagery is drawn from the symbolic world of the ancient Near East (see notes in chs. 7–12). The use of numbers in apocalyptic texts tends to be symbolic as well and should not be used to create a calendar of the end times. While prophecy is often conditional based on the response of the audience, apocalyptic visions like Daniel’s announce the certain destruction of evil forces, an encouraging message to the faithful who suffer at their hands.

Themes and Theology

A focus on God’s sovereignty unites the six stories and four visions. Though it looks like evil is in control, God really is. From a human perspective, Nebuchadnezzar took the city of Jerusalem in the third year of Jehoiakim, but the book of Daniel reveals that he did so only because God allowed him to do so (1:1–2). Furthermore, it looks like the evil forces of the world will win the victory, but at the end of the stories it is God’s people who come out on top, and at the end of the visions it is God who defeats the evil human kingdoms that oppress his people.

No OT book has a more pronounced picture of the kingdom of God versus the kingdoms of this world than the book of Daniel. The kingdom of God (the rock not formed by human hands) will destroy the kingdoms of the world (the multi-metaled statue; 2:31–45). The “one like a son of man coming with the clouds” (7:13) will lead the saints of the Most High in battle and win the victory over the beasts and their horns. God’s kingdom, an everlasting kingdom, will succeed the kingdoms of the world (7:27).

Thus, the book of Daniel models how God’s people should live in this world torn by evil forces. Knowing that God’s victory is assured and that his kingdom will prevail, they should share the courage, confidence, and hope of Daniel and his three friends. While God’s persecuted people can survive and even prosper in a toxic culture, they should be ready to face death (3:16–18), knowing that even death is not beyond God’s rescue. Perhaps for this reason, Daniel has the OT’s clearest statement of personal, physical resurrection (12:1–3).

The book of Daniel anticipates the coming of God as a warrior who will defeat the forces of evil and establish his kingdom. The NT depicts Jesus Christ as the one who wins the battle, first by defeating Satan on the cross (Col 2:13–15) and then completing the victory when he returns in his second coming. In this connection, the book of Revelation, the NT’s apocalyptic book, frequently alludes to the book of Daniel. For instance, the image of ultimate evil in the book of Revelation is the beast that arises out of the sea (Rev 13), reminiscent of the four beasts that arise out of the sea in Dan 7. Jesus is the one who, “like a son of man” (Rev 1:13; see Dan 7:13), rides the clouds to battle the powers of evil (Matt 24:30; Mark 13:26; 14:62; Luke 21:27; see Dan 7:13–14). Daniel’s description of the Ancient of Days in Dan 7:9 resembles the description of the one “like a son of man” in Rev 1:12–16.

Outline

I. Daniel and the Three Friends in a Foreign Court (1:1—6:28)

A. Daniel’s Training in Babylon (1:1–21)

1. The Subjugation of Judah (1:1–2)

2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Training Program (1:3–5)

3. Name Change (1:6–7)

4. Refusing the King’s Food (1:8–16)

5. Valedictorians (1:17–21)

B. God’s Wisdom Versus Babylonian Wisdom (2:1–49)

1. The King’s Disturbing Dream (2:1–13)

2. God’s Wisdom (2:14–30)

3. The King’s Dream (2:31–35)

4. The Interpretation of the Dream (2:36–45)

5. Nebuchadnezzar Praises the True God (2:46–49)

C. The Image of Gold and the Blazing Furnace (3:1–30)

1. The Image of Gold (3:1–7)

2. The Three Friends Accused (3:8–18)

3. God’s Miraculous Rescue (3:19–27)

4. Nebuchadnezzar Worships God (3:28–30)

D. The King’s Pride Humbled (4:1–37)

1. The King Praises God (4:1–3)

2. The Dream Report (4:4–18)

3. Daniel Interprets the Dream (4:19–27)

4. The Dream Is Fulfilled (4:28–37)

E. The Writing on the Wall (5:1–31)

1. The King Profanes the Holy Goblets (5:1–4)

2. The Writing on the Wall (5:5–12)

3. Daniel’s Interpretation (5:13–28)

4. Daniel’s Reward and Babylon’s Punishment (5:29–31)

F. Daniel in the Den of Lions (6:1–28)

1. The Plot Against Daniel (6:1–9)

2. Darius Reluctantly Punishes Daniel (6:10–18)

3. Daniel’s Rescue (6:19–24)

4. Darius’s Decree (6:25–28)

II. Four Apocalyptic Visions (7:1—12:13)

A. The First Vision (7:1–28)

1. Daniel’s Dream of Four Beasts (7:1–14)

2. The Interpretation of the Dream (7:15–28)

B. The Second Vision (8:1–27)

1. Daniel’s Vision of a Ram and a Goat (8:1–14)

2. The Interpretation of the Vision (8:15–27)

C. The Third Vision (9:1–27)

1. Daniel’s Prayer (9:1–19)

2. The Seventy “Sevens” (9:20–27)

D. The Fourth Vision (10:1—12:13)

1. Daniel’s Vision of a Man (10:1—11:1)

2. The Kings of the South and the North (11:2—12:4)

3. Final Words (12:5–13)

![]()

![]()

![]()