Author

The book opens with a thunderclap: “the word of the LORD” (1:1). God’s message “came” through Micah’s personality, spirit, language, and voice. Micah was also the Lord’s pen. His name frames the book. “Micah” (1:1) means “who is like the LORD?” and in the book’s last stanza the author asks, “Who is a God like you . . . ?” (7:18). If this pun is intentional, Micah probably authored this unified book. Two more obvious sutures, besides those mentioned in the notes, show that Micah compiled and arranged his prophesies delivered over a span of years (see Date and Addressees): “Then I said” (3:1a) stitches together two cycles of prophecies (chs. 1–2 and chs. 3–4). “But as for me” (7:7) provides a smooth transition from the Lord’s dirge in (7:1–6) to Zion’s song of victory (7:8–20). Unlike Isaiah and Amos, Micah does not mention his call to be a prophet, but he does testify that he is “filled with power, with the Spirit of the LORD, and with justice and might” (3:8). His use of “we,” “us,” and “our” (e.g., 5:6; 7:19) identifies him with Israel’s faithful remnant (see 2:12). He is a man of prayer and of faith (7:7). Against the normal custom of identifying oneself as the son of a father, Micah identifies himself by his hometown, Moresheth Gath (1:1, 14), suggesting he was an outsider to Jerusalem. The fulfillment of his prophecies validates him as a true prophet (cf. Deut 18:22; Jer 26:17–19). This validation and the convincing work of the Holy Spirit led God’s people immediately to recognize his book as the inspired “word of the LORD” (1:1), as is true of all the canonical books (2 Tim 3:16).

Date and Addressees

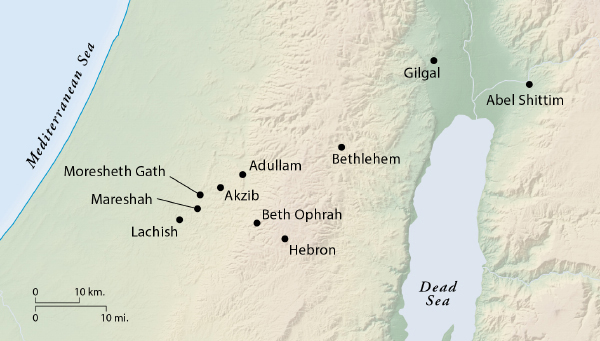

Micah prophesied between 750 and 686 BC and into the seventh century to the leaders of Samaria (the capital of the northern kingdom) and of Jerusalem (the capital of the southern kingdom). The kings of Samaria were pretenders to the throne, lacking prophetic sanction (cf. Hos 8:4), so Micah names only the kings of Jerusalem: Jotham (750–732/31 BC), Ahaz (735–716/15), and Hezekiah (729–687/86). His contemporaries were Hosea in Samaria (Hos 1:1) and Isaiah in Jerusalem (Isa 1:1). In his prophecies Micah names neither the leaders of Israel nor Israel’s enemies, except for “Babylon” (see 4:10 and note) and “Assyria” and the “land of Nimrod” (see 5:6 and note). This lack of historical specificity evokes more elevated sentiments and facilitates a more universal application. Nevertheless, some prophecies can be better understood by creating scenarios for them from Micah’s historical background. Micah predicts the fall of Samaria to Assyria (1:2–7), which happened in 722 BC. His judgment-prophecies reflect social conditions prior to Hezekiah’s reforms about 701 (Jer 26:19). Micah’s naming of “Assyria” and the “land of Nimrod” in 5:6 reflect Micah’s time, when Assyria reigned over Babylonia. His language is preexilic Hebrew. No scientific evidence disputes the claims of the book’s title.

Micah originally addressed Samaria and Jerusalem. His prophecy “Jerusalem will become a heap of rubble” (3:12) led Hezekiah to repent (Jer 26:19). In its canonical form, his prophecy about the Messiah’s birthplace guided the Magi to Bethlehem (5:2; Matt 2:1–11). The book of Micah still speaks. When the Library of Congress in Washington DC was rebuilt in the late nineteenth century, prominent religious leaders, after considering notable quotes from all known religious literature, chose Mic 6:8 as the motto for the alcove of religion. His book comforts the church in sorrow, restrains her from temptation, and nerves her to fidelity in testing.

Historical Background

Assyrian annals give us firsthand knowledge of the Assyrian invasions of Israel at this time. Matching those annals with biblical texts (cf. 2 Kgs 15:29—20:21) this relevant picture emerges:

1. Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) in 733 took Gilead and much of Galilee and deported the people to Assyria (2 Kgs 15:29).

2. Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC) besieged Samaria for three years and captured it in 722 (2 Kgs 17:5–6).

3. Sargon II (722–705 BC) claims to have captured Samaria, but it was more likely a mopping-up operation. He deported the large property holders, rulers, and religious leaders from Samaria.

4. Sennacherib (705–681 BC) in 701 overran Judah because Hezekiah had joined Babylon and Egypt in a revolt against the Assyrian king (2 Kgs 18–20; Isa 38–39).

Message

In a nutshell, the Lord’s message through Micah is that God’s kingdom comes through his keeping his covenants with Abraham (Gen 22:17–18), Moses (Deut 5–28), David (2 Sam 7:12–16) and all Israel in coming days (Jer 31:31–34). Micah accuses Israel’s civil and religious leaders of crimes against the Mosaic covenant (Deut 5:6–21) and sentences them to punishment according to its curses (Deut 28:15–68). Micah’s salvation-prophecies fulfill the Lord’s oath to Abraham (7:20) and also fulfill his prophecy through Moses regarding Israel’s restoration after exile (Deut 30:1–10). Micah’s prophecy, that Messiah’s origins are in the loins of David (see 5:2 and note), fulfills the Davidic covenant (5:1–6; Isa 11:1). As for the people of Israel, Micah prophesies that their sins will be forgiven (7:18) and they will know the Lord (cf. 6:5) and keep his law within their hearts (cf. 6:8)—all of which fulfill the promises of the new covenant and Moses’ prophecy. Spiritually strengthened by Micah’s salvation-prophecies, God’s people walk in a way becoming God’s name (4:5) and wait in hope for the triumph of God’s kingdom (7:7).

Today the seed of Abraham is the church, those who have been baptized into Jesus Christ (Gal 3:29). Christ took the curse of God’s judgment in the church’s stead, and through his church Christ is making disciples of all nations (Matt 28:18–20). According to the apostle Paul’s theology of the remnant, it is possible that at the end of salvation-history all of ethnic Israel will experience the blessings of God’s covenants (Rom 11:1–32).

Content

The book consists of about 20 judgment and salvation prophecies. Judgment-prophecies consist of two essential motifs: accusation and judicial sentence. Their function is to lead God’s people to repentance (Jer 18:7; 26:17–19). Salvation-prophecies promise God’s people salvation “in the last days” (4:1). If they speak of God’s judgment, they represent the judgment as a historical fact, not as a threat of judgment against the accused. Micah arranged his judgment- and salvation-prophecies in a meaningful way and in a way that yields meaning. There are three cycles of first judgment prophecies and then salvation prophecies. Each cycle begins with the same Hebrew word, which is translated “hear” (1:2) and “listen” (3:1; 6:1).

Outline

I. Title (1:1)

II. First Cycle (1:2—2:13)

A. Judgment-Prophecies Against Samaria and Jerusalem (1:2—2:11)

1. Prophecy Against Samaria (1:2–7)

2. Prophecy Against Jerusalem (1:8–16)

3. Prophecy Against Land-Grabbers (2:1–5)

4. Prophecy Against Land-Grabbers and False Prophets (2:6–11)

B. A Salvation-Prophecy: A Remnant Delivered (2:12–13)

III. Second Cycle: (3:1—5:15)

A. Judgment-Prophecies Against Israel’s Leaders (3:1–12)

1. Prophecy Against Unjust Rulers: Shepherds Turned Cannibals (3:1–4)

2. Prophecy Against False Prophets: Prophets for Profit (3:5–8)

3. Prophecy Against Rulers, Prophets, and Priests: Jerusalem Leveled (3:9–12)

B. Salvation-Prophecies (4:1—5:15)

1. Exaltation of Zion (4:1–5)

2. Restoration of the Remnant: Lame Become Strong (4:6–7)

3. Restoration of Zion (4:8)

4. The Lord’s Secret Strategy: Captivity to Freedom; Besieged to Victory (4:9–13)

5. A Promised Ruler From Bethlehem (5:1–6)

6. The Remnant Among the Nations: Life and Death (5:7–9)

7. The Lord Purges and Protects His Kingdom (5:10–15)

IV. Third Cycle: (6:1—7:20)

A. Judgment-Prophecies (6:1—7:7)

1. The Lord’s Case Against Israel (6:1–8)

2. Covenant Curses Fulfilled (6:9–16)

3. A Dirge: Israel’s Misery (7:1–6)

B. Personal Testimony: Hope in Darkness (7:7)

C. Salvation-Prophecies: A Song of Victory (7:8–20)

![]()

![]()

![]()