Author

Ephesians is the quintessential Pauline document, summing up many important themes of Paul’s letters and of his ministry as the Apostle to the Gentiles. The letter claims to be written by Paul himself (1:1; 3:1). Nevertheless, the unusual linguistic style and verbal similarity with many parts of Colossians lead some to suggest that Ephesians is pseudonymous, written by an imitator who relied on Colossians. The NT (2 Thess 2:2; 3:17; see Introduction to 2 Thessalonians: Author) and the early church fathers, however, rejected pseudonymity. The literary relationship between Ephesians and Colossians is better explained on the assumption that Paul composed both works at the same time and that he modified the themes of each letter for different readers facing different circumstances.

Date, Place of Composition, and Destination

Paul wrote Ephesians probably in AD 60–61 during his Roman imprisonment. The destination of the letter is debated. The phrase “in Ephesus” (1:1) is lacking in some early manuscripts, suggesting that the letter is written not specifically “to God’s holy people in Ephesus” (1:1), but broadly to “God’s holy people” in southwestern Asia Minor. This conclusion is consistent with the impersonal nature of the letter. Eph 1:15 and 3:2 imply that Paul and his readers only heard reports of each other. The letter also lacks personal greetings (cf. Rom 16; Col 4:10–17) that would be present if it were addressed primarily to the believers in Ephesus since Paul spent three years there (Acts 19:8, 10; 20:31) and knew the elders well (Acts 20:17–38). So Ephesians is probably a circular letter Paul sent to Gentile believers in the churches of southwestern Asia Minor. It was eventually connected with Ephesus because of the importance of that city and because it was one of the cities to which Paul sent the letter.

City of Ephesus

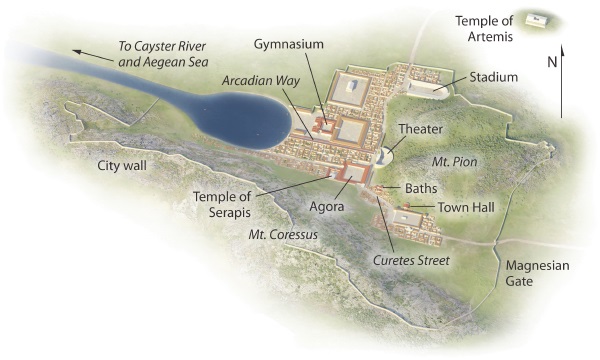

With an estimated population of 200,0000–250,000, Ephesus was called the “mother city” of Asia. Economically, Ephesus was the largest trading center in western Asia Minor. Located on the mouth of the Cayster River, which emptied into the Aegean Sea, Ephesus had a harbor (now silted up) that provided access to major shipping routes. In addition, Ephesus was situated at the intersection of major land routes.

Religiously, Ephesus had the honor of being the “guardian of the temple of the great Artemis and of her image, which fell from heaven” (Acts 19:35). The temple of Artemis (the Roman goddess Diana) was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and the influence of the Artemis cult pervaded every facet of life in the city. Artemis was considered the guardian of the city, her temple served as the primary banking institution of the city, her image graced the coinage, and festivals and games were held in her honor. The worship of Artemis was not restricted to Ephesus. Demetrius, a silversmith in Ephesus, claimed that Artemis was “worshiped throughout the province of Asia and the world” (Acts 19:27).

Paul preached in Ephesus over a period of three years with the result that “all the Jews and Greeks who lived in the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord” (Acts 19:10; cf. 19:26). He also did extraordinary miracles and cast out demons (Acts 19:11–16). Many believed in the Lord and those who formerly practiced sorcery burned their scrolls, the value of which totaled “fifty thousand drachmas” (Acts 19:19). Opposition arose and Paul narrowly escaped a huge mob in the theater (Acts 19:23–41). The theater still stands today and could possibly seat 25,000 people. For other civic structures familiar to Paul, see the following map. The location of the “lecture hall of Tyrannus” (Acts 19:9) is unknown.

Occasion and Purpose

Ephesians is the least situational of all Paul’s letters because it does not explicitly address any specific problem. But as a circular letter, it is a manifesto for the church, describing its essence and identity: who it is, how it came about, how it must conduct itself, and what its mission is within the larger framework of Christ’s cosmic rule. As such, Ephesians develops a major theme in Colossians: cosmic reconciliation in Christ. Although not explicitly stated, this theme of reconciliation presupposes that the cosmos did not remain in the condition in which God created it. The unity and harmony of creation was ruptured (Rom 8:18–22) and needed a reconciliation or new creation to recover the original state. Although Colossians and Ephesians share this common narrative of alienation and reconciliation, there are differences. Colossians emphasizes Christ’s role in both creation and reconciliation; Ephesians emphasizes reconciliation. Colossians emphasizes the reconciliation of the cosmos and humanity to God; Ephesians carries this theme but also emphasizes the reconciliation between Jews and Gentiles. Moreover, Ephesians draws out the implications for how this reconciled humanity, the church comprising Jews and Gentiles, must understand its identity and function within God’s grand vision of cosmic peace and unity in Christ.

Genre and Structure

Ephesians follows the standard pattern of a Hellenistic letter with an opening (1:1–2), body (1:3—6:20), and closing (6:21–24). The body of the letter broadly divides into two parts: doctrinal (1:3—3:21) and ethical (4:1—6:20).

Themes

Unity

The two parts of the letter’s body (1:3—3:21 and 4:1—6:20) support the letter’s central message: peace and unity in Christ. Chs. 1–3 present the foundational story of how the church must understand its identity within God’s vision of cosmic unity in Christ. God chose the church before the creation of the world (1:4) and made known to it his plan of uniting all things in Christ (1:9–10). Central to this plan is the unity of the church, a unity in which vertical reconciliation to God (2:1–10) forms the basis of horizontal reconciliation between Jews and Gentiles (2:11–22). Paul elaborates further on this union of Jews and Gentiles into one body (3:1–13): the church’s function is to proclaim the reality and wisdom of God’s cosmic plan of reconciliation to the “rulers and authorities in the heavenly realms” (3:10). Paul prays that his readers will comprehend the love of Christ and love one another (3:14–21) so they can live out the unity they have in Christ.

Chs. 4–6 exhort the church to conduct itself in light of its calling within God’s plan of peace and unity in Christ. Believers are to maintain the church’s unity (4:1–16) by embracing the corporate ethos of their new identity (4:17—5:20), establishing household unity (5:21—6:9), and standing together against a common enemy (6:10–20).

Christ

Ephesians, like Colossians, presents a cosmic Christ. Christ brings all of history to completion (1:10). He is seated at the right hand of God, exalted above all spiritual powers, and is the authoritative head over everything (1:20–22). He possesses “boundless riches” (3:8), and he freely gives gifts to the church (4:7–11). While focusing on Christ’s resurrection, exaltation, and enthronement, Ephesians also speaks of his death on the cross as the basis for redemption and reconciliation (1:7; 2:13, 16; 5:2, 25). Ephesians, like Colossians, uses the phrase “in Christ” more than Paul’s other letters. This expression is probably rooted in Paul’s understanding of Christ as a corporate figure. As Adam determines the fate of all who belong to him, Christ also determines the fate of those who exercise faith and are “in him” (see Rom 5:12–21; 1 Cor 15:22). Thus, those who are “in Christ” are united with him and participate in his death, resurrection, and new life. They have a new identity that necessitates reorienting one’s entire existence (2 Cor 5:14–17). In Ephesians and Colossians, Paul expands the use of this language to a cosmic scale such that the creation and redemption of the cosmos is also said to be “in Christ” (Eph 1:9–10; 3:11; Col 1:16–17). Despite the overlapping occurrences of this expression between the two letters, Ephesians differs by using it more significantly to denote the basis on and the sphere in which believers have fellowship not only with God but also with one another. Vertically, Christ connects God and the church; horizontally, Christ connects all believers, even those who come from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds.

Church

Although “church” generally denotes a local assembly or congregation in Paul’s earlier letters (Rom 16:5; 1 Cor 1:2; Gal 1:2; 1 Thess 1:1), the term in Ephesians always has a wider reference and designates the universal church to which all true believers belong.

Paul describes the church using several metaphors:

A body. Organically, the church is a body whose head is Christ (5:23). As a body, the different members of the church are dependent on one another (4:12–16) and exemplify the necessity of unity in diversity. As the body of Christ, the church depends on Christ for its growth (4:16) and submits to his headship (5:24). This introduction of Christ as the head of the church is a distinctive contribution of Ephesians (and Colossians).

A temple. Architecturally, the church is a holy temple filled with the presence of God and built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone (2:20–22).

A commonwealth. Politically, the church is a commonwealth that embodies the reconciliation of two former hostile ethnic groups (2:11–22) and that battles evil spiritual powers (6:10–20).

A household. From the perspective of social structures, the church is a household unit in which God is the Father (1:3, 17; 2:18; 3:14; 4:6; 5:20; 6:23) and believers are adopted as his children through Jesus Christ (1:5; 2:19).

A bride. Drawing on the OT depiction of Israel as the bride of Yahweh, the church is also portrayed as the bride of Christ (5:23–32). He cares, feeds, and sanctifies the church in order that he might present it to himself as radiant, “without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish” (5:27). As his wife, the church submits to Christ.

Trinity

Unlike the Gospel of John, Ephesians does not contain any explicit Trinitarian language stating that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (or the Father and Son) are one. Nevertheless, it uses suggestive Trinitarian language (1:17; 2:18, 22; 3:14–17; 5:18–20), highlights the collective work of the Trinity in effecting reconciliation (1:3–14), and bases the unity of the church on one Spirit, one Lord, and one God and Father (4:4–6). Early church fathers, such as Ignatius, adopted such Trinitarian language as the basis for the unity of the Trinity, and they used the unity of the Trinity as the basis for the unity of the church.

Outline

I. Letter Opening (1:1–2)

II. Calling of the Church Within Christ’s Cosmic Reconciliation (1:3—3:21)

A. Praise for Spiritual Blessings in Christ (1:3–14)

B. Thanksgiving and Prayer (1:15–23)

C. Made Alive in Christ (2:1–10)

D. Jew and Gentile Reconciled Through Christ (2:11–22)

E. God’s Marvelous Plan for the Gentiles (3:1–13)

F. A Prayer for the Ephesians (3:14–21)

III. Conduct of the Church Within Christ’s Cosmic Reconciliation (4:1—6:20)

A. Unity and Maturity in the Body of Christ (4:1–16)

B. Instructions for Christian Living (4:17—5:20)

C. Instructions for Christian Households (5:21—6:9)

D. The Armor of God (6:10–20)

IV. Final Greetings (6:21–24)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()