While awaiting the anticipated Fenian attack on St. Patrick’s Day, Lieutenant-Governor Gordon took full advantage of the time available to improve defence arrangements and resolve problems. In these endeavours, he was ably assisted by Lieutenant Colonel George Joseph Maunsell, an ex-captain of the 15th Regiment who served as adjutant general of the New Brunswick militia. To ease Maunsell’s growing work load, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew C. Otty, from the King’s County Militia, was appointed deputy adjutant general. Otty was tasked “to examine” the frontier posts and report his findings directly back to Gordon. The resolution of the unsatisfactory state of the St. Andrews militia was a priority. As noted in the St. Andrews Standard, “The appointment of Col. Otty … is most opportune; the Colonel’s ability and popularity as a Militia officer, will secure him a welcome, and result in the organization we hope of our ‘disorganized Battalion’ to use the words of one of his officers. Col. Otty ‘is the right man in the right place,’ and a thorough soldier.”

Otty arrived in St. Andrews on December 28, 1865. After taking up quarters in the Railroad Hotel, he held discussions with Captain James and met with the home guard. The exchange between the militiamen and Otty was direct and frank. The men wanted the right to elect their officers. Otty made it clear that this would not happen, as the commander-in-chief retained the sole right to commission officers. With Colonel Boyd in mind, they asked, “will you give us a guarantee, if we do Volunteer we will not be placed under the control of a person who is decidedly obnoxious to the majority of us.” Otty responded again that it was the commander-in-chief ’s prerogative to select the officers. The volunteers were encouraged, however, when Otty promised that any approved company would be under the direct control of Gordon, properly armed, provided with a qualified drill instructor and would not be subjected to unnecessary paperwork. Otty explained that he would not make any recommendations to Gordon until he had visited St. Stephen and Woodstock and reviewed their defence measures. Otty returned to St. Andrews on January 8. The home guard was reinstated under Captain James, and a Class A volunteer company of the active militia was approved under the command of Captain Edward Pheasant. To show their delight, members of the new company requested that they be called the Gordon Rifles.

Otty believed that a second volunteer unit could be raised in St. Andrews without detriment to the Gordon Rifles and recommended the formation of an artillery battery. By mid-January, a new battery of artillery was organized with a strength of forty-one gunners under the command of Captain Henry Osborne. This new battery became part of Colonel Foster’s New Brunswick Regiment of Artillery. Although the volunteer militia and home guard had been placed on a sound footing, dissatisfaction continued in 1st Battalion Charlotte County Militia. On March 14, a public meeting was held to enrol the militia, but only nine volunteered for service because of the unpopularity of Colonel Boyd.

Otty moved on to St. Stephen where he found defence measures well advanced. The St. Stephen Volunteer Company drilled under Drill Sergeant T. Quinn of the British 10th Regiment and, as reported in the Saint Croix Courier, was “growing daily in numbers and efficiency.” Captain T. J. Smith, the company commander, was actively involved and had finished the armory at his own expense, making it “a pleasant and inviting place to meet.” Colonel Foster of the New Brunswick Regiment of Artillery and Captain William T. Rose had discussed the establishment of an artillery battery in St. Stephen. By the end of January, artillery training had commenced under the direction of Sergeant Connolly. On February 24, 1866, the lieutenant-governor inspected the St. Stephen Volunteer Rifles and was very complimentary. He is quoted in the Saint Croix Courier as saying “that nearly all present had only been drilling since the commencement of the winter, and he was surprised and gratified to observe the progress they had made.”

The defence measures envisaged by the lieutenant-governor in Carleton County met both successes and failures. In response to Colonel Tupper’s appeal, over one hundred men enrolled in the Centreville Home Guard. Some of these recruits believed that they would elect their officers and became disgruntled when Tupper appointed Captain William Dell Estey and Lieutenant Charles A. West as the company officers. In a scathing letter to the editor of the Carleton Sentinel, one of the recruits, Henry T. Scholey, claimed this violated his right as a Briton, and he and seventy others refused to drill. Captain Estey was quick to rebut with another letter, stating that the Centreville Home Guard still existed and was successfully parading with over thirty men. He emphasized that only the commander-in-chief had the authority to appoint officers and that poor Scholey “did not know any better, therefore the sin of ignorance in this particular case, should be winked at.” Captain Estey was also quick to inform Scholey in writing that his name had been “erased” from the home guard.

There was also confusion concerning the home guard in the Town of Woodstock. Following the lieutenant-governor’s appeal in mid-December, almost one hundred men enthusiastically enrolled in the guard. They then elected their officers and divided into two companies under the command of Captains John Leary and William Lindsay. Colonel Baird, however, refused to acknowledge these home guard companies with their elected officers. Instead, Baird ordered Lindsay, an ensign in the county militia, to start the process again and form a new home guard with Lindsay as an appointed officer, but he refused. Attempts to appeal directly to the commander-in-chief over the head of Colonel Baird failed. The original companies continued to drill under their elected officers without official sanction, leaving the status of the Woodstock Home Guard unresolved. Despite this controversy, the Woodstock Volunteer Rifle Company under the direction of Captain George Strickland, Lieutenant Baird and Ensign G. E. Boyer drilled and expanded. This Class A company received public acclaim after a fire destroyed the building housing Belyea’s store and dwelling on King’s Street, and Captain Strickland, “with his usual forethought,” detailed members of his company to stand guard over the exposed property. Strickland again received public notice when it was learned that he had established a “reading room” for the benefit of his men. In addition to the Woodstock Volunteer Rifle Company, Colonel Baird had under his command another 302 men in home guard units located outside Woodstock. At the same time, a Class A volunteer rifle company had been successfully raised in the Centreville-Wicklow area under the command of Captain Issac Adams. It held regular drill parades in the recently erected Centreville drill hall. In training his company, Captain Adams had the benefit of having attended the 1865 Camp of Instruction. At the end of January, the Carleton Sentinel reported “They certainly are a firm looking body of men, and performed their drill well.”

Musket carried by Private H.E. Hill of No. 1 Company, St. Stephen Rifles, during the Fenian crisis. The musket is a New Land Pattern, light infantry model, which came into production in 1802. The lock is marked ‘Tower’ and has the crown of George III. The lack of more modern arms necessitated the use of these outdated weapons during the Fenian crisis. Private Collection

The defence of the City of Saint John was based on the Saint John Volunteer Battalion and the three hundred men in the volunteer artillery batteries. Colonel Crookshank felt he was unable to devote the necessary time and attention to the volunteer battalion at this time of crisis and requested six months’ leave of absence. The vacancy was filled on January 17, 1866, with the appointment of Lieutenant Colonel Otty as the acting commanding officer. He took charge immediately, devoting all his time to his military duties. Otty set up training programs for officers and non-commissioned officers. Captain Cyprian Edward Godard raised a seventh company in the Portland district. As well, the uniquely uniformed “Zouaves” company was disbanded and replaced with a company commanded by Captain Charles Campbell. Military experience and professionalism arrived with the selection of Sergeant Thomas McKenzie of the 64th Regiment as sergeant major and Sergeant McCreary of the 2nd Queen’s Own Regiment as drill instructor. Drills were held regularly and an alert system developed to assemble the battalion quickly in an emergency. In preparation for the anticipated emergency on St. Patrick’s Day, Gordon called out the Saint John Volunteer Battalion on active service on March 14, with a paid strength of eighteen officers and 418 men. On the same day, Captain George H. Pick’s volunteer battery of artillery, consisting of three officers and eighty-three gunners, was also called out. Both units were placed under command of Brevet-Colonel John Amber Cole, the commander of Her Majesty’s troops in New Brunswick.

As St. Patrick’s Day approached, public apprehension grew. On March 7, the St. Andrews Standard, quoting from a telegram received from New York, reported that the Fenian General Sweeny would make a demonstration against Canada “about the middle of March with a small force and strike New Brunswick via the Maine frontier with his main column.” The newspaper went on to decry the lack of artillery and proper arms for the home guard. This perceived threat resulted in a run on the banks in Saint John forcing the management of the Savings Bank to seek financial support from Baring Brothers in London. Colonel Cole was sent to Saint John to take command of its defence. With little time to prepare, he swung immediately into action. He placed guards from the volunteer battalion on the magazines, armories, military storehouses and other vital points around the city. Detachments from the artillery battery were stationed on Partridge Island, at Reed’s Point Battery and the Carleton Martello Tower. The British regulars of the 15th Regiment stationed in Saint John were concentrated in Barrack Green, placed on alert and held in readiness to respond wherever and whenever required. When the attorney general was questioned in the legislative assembly about the measures taken to protect the province against the Fenians, the government replied that adequate steps had been put in place. Gordon, however, knew differently. When Major General Sir Charles Hastings Doyle, the commander of the British Forces in the Lower Provinces, asked what support he could expect from the provincial militia, Gordon had to admit very little was available.

Two unidentified privates of the Saint John Volunteer Battalion, circa 1863. NBM X12539

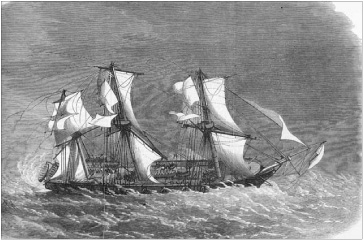

The defence of the Port of Saint John received a major boost with the arrival of HMS Pylades. A request for a British warship to protect Saint John had been made during the panic in December, but had been rescinded. With growing concern over a Fenian incursion, the lieutenant-governor made another request on February 1. The senior naval officer in Halifax sent a warship immediately. With only one ship in port, the choice was easy: HMS Pylades, a 1,278-ton steam corvette with a crew of 274 men, a 20-cannon broadside and two 110-pounder Armstrong guns fore and aft was sent. Under the command of Captain Arthur W. A. Hood, it arrived in Saint John on February 6, coated in ice after a difficult winter passage. The Pylades was expected to remain until spring.

Following his arrival in Saint John, Captain Hood remained onboard his ship for more than a week. As Colonel Cole explained to Gordon, “he has returned from 2 years West Indies and cannot face cold … and it is enough to drive him into the Asylum.” Less fortunate was Pylades’ Lieutenant Pauline, who took a chill on the voyage from Halifax and after a short illness, in the era before antibiotics, died of “congestion of the lungs.” On March 29, a large crowd of Saint Johners watched the spectacle of a naval funeral conducted by the ship’s company, with Pauline’s coffin transported on a gun carriage, a firing party and the band of the 15th Regiment playing the Death March.

Captain Hood informed Gordon that his instructions from the British Admiralty directed him to provide “any assistance you may require for the protection of St. John from any attack that may be made on it by a band of Fenians from the United States.” Hood explained that when his ship was on alert it took only two hours to raise steam in order to sail. In discussing how best to employ HMS Pylades, Hood suggested positioning it in Passamaquoddy Bay, where the Fenians could be intercepted departing Maine. However, he made it clear that if Gordon so directed he would remain in Saint John. In the event, HMS Pylades stayed in Saint John for the next two months.

“HMS Pylades in a Squall,” from the Illustrated London News, dated December 4, 1869. The Pylades played a major role in the Fenian crisis.

Archives & Special Collections, Harriet Irving Archives, University of New Brunswick

By early March, the province of Canada was also in a state of alarm. Intelligence continued to indicate increasing Fenian activity and St. Patrick’s Day as the likely date of attack. As a result, the adjutant general of the militia directed that ten thousand volunteers assemble for active service for a three-week period. The response was so overwhelming that fifty thousand men could have been raised, and, after further consideration, the number of men called out was increased to fourteen thousand. As in New Brunswick, this force was deployed to watch the approaches to frontier towns and protect vital points along the border.

The long anticipated St. Patrick’s Day proved to be anti-climatic. The Saint John Morning News reported that “the long talked of and ominous St. Patrick’s Day arrived on Saturday morning, and a more mild, pleasant, genial one than it proved to be could scarcely be experienced at this early season. It came we have already said, in peace, and we have now to add that it departed in the same spirit.” The St. Andrews Standard noted that “St. Patrick’s Day passed off here in an unusually quiet manner. Not even the hard working man had his heart warmed by a swig of mountain dew. It was too quiet by half.” The Carleton Sentinel said, “Saturday last, St. Patrick’s Day, passed off very quiet in Woodstock, there being no public demonstration whatever. Many persons throughout the country were impressed with the belief that this was the day on which O’Mahoney [sic] with his army was to make his onslought [sic] on us.” The Fredericton Headquarters reported that St. Patrick’s Day passed without incident and gave credit to Gordon’s defence measures for securing the peace for the province. March 17 also passed without incident in Canada. The only reported excitement was the firing of some guns and rockets across the border at Lubec, Maine. Both the lieutenant-governor and the general public, however, believed that a Fenian attack was yet to come and de-fence preparations continued unabated.

Major General Sir Charles Hastings Doyle, the commander of British Forces in the Lower Provinces during the Fenian crisis. PANB P360-14