After the St. Patrick’s Day scare, Lieutenant-Governor Gordon reassessed the threat posed by the Fenian Brotherhood. He concluded that a major invasion across the Maine border was unlikely and, assuming the continued presence of the Royal Navy in the Bay of Fundy, so was an attack on Saint John. Gordon believed that an attempt by the Fenians to seize either an island in the Passamaquoddy Bay or some location near St. Andrews was still conceivable, but a series of raids across the Maine border remained the most likely possibility. Since the British regulars stationed in New Brunswick formed ready reserves in Fredericton and Saint John, it followed that the defence of the frontier must rest primarily upon the provincial militia.

In developing a plan, Gordon turned for advice to General Doyle, the British commander-in-chief in the Lower Provinces. In the discussions that followed, it quickly became apparent that Gordon, the public servant, and Doyle, the professional soldier, had widely differing views on defence. Doyle, a veteran of the Crimean War, saw a thousand kilometers of border to defend, including a number of isolated islands. Based on his extensive experience, Doyle knew this was an impossible task, particularly when taking into account the limited military resources available. Not all approaches across the Maine border could be protected, and those covered could not be adequately defended. The conventional military solution for such a defence problem was to concentrate military resources well back in a central location, wait for the enemy to attack and then deliver a counter-stroke against the flanks and rear of the invading columns. The suggestion that they abandon the frontier communities was totally unacceptable to the lieutenant-governor. He firmly believed it would be morally wrong to yield territory to the Fenians, and he knew the provincial government would reject such a plan outright. The people in the frontier region would feel betrayed, particularly after having wholeheartedly supported Gordon’s recent defence initiatives. It would prove detrimental to public support for the militia and disastrous for recruiting. Gordon also argued that the capture and occupation of a frontier community would be a major psychological victory for the Fenians, providing them with a tremendous boost to their cause, recruiting and fundraising. In the end, the military commander acquiesced to the civil leader and Gordon’s point of view prevailed.

The next step taken by the lieutenant-governor was to ensure he had the support of the legislative assembly. Gordon informed the house that it may be necessary “to call out a portion of the Provincial Militia Force to co-operate with Her Majesty’s Regular Troops in New Brunswick.” He wanted to be “in the firm confidence that any measures needful for the protection of the Province from marauding bands will meet with the most hearty concurrence and support of the Legislature and Loyal people of New Brunswick.” The militia budget for 1865 had been $30,000, and in 1866 the amount budgeted was $40,000, with the increment to cover additional volunteers and an increase to allowances. Gordon explained that “the amount of extraordinary expenditure to be incurred in measures of precaution, it is of course, difficult to estimate, as it must mainly depend” on the length of time the emergency lasts. Gordon suggested the legislature be prepared to spend an additional $30,000 to $50,000. The legislative assembly readily gave the support that Gordon sought by unanimously passing the resolution, “that the House, representing the whole people of the Province, will provide for all precautionary measures that the Executive Government may deem necessary in the present emergency for the defence of the country.” Despite stringent measures to control expenditures, the total cost of the emergency to the province of New Brunswick would amount to a staggering $112,000.

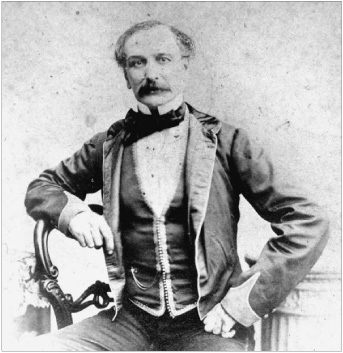

Brevet Colonel John Amber Cole, the commander of British troops and provincial militia on active service in New Brunswick during the Fenian crisis. PANB P272-621

The senior military officer in New Brunswick, Brevet Colonel John Amber Cole of the 15th Regiment, had under his direct command all British troops stationed in New Brunswick and all units of the provincial militia called out on active service. Commanding officers on call-out received their orders from Colonel Cole, or officers appointed by him, except for matters of pay and promotion, which were the purview of Lieutenant Colonel Maunsell, adjutant general of militia. Those on active service were subject to the Articles of War, the act that provided for punishing mutiny and desertion, and all other laws applicable to British regular soldiers.

The Western Military District, located along the Maine border, was the area of greatest concern. The lieutenant-governor appointed Captain Thomas Anderson as district commander effective March 14, 1866, with the New Brunswick militia rank of lieutenant colonel. Anderson had extensive military experience, including service with the 78th Highland Regiment during the Indian Mutiny. Upon retiring from the British Army, he was assigned to the Saint John Volunteer Battalion for a year and then appointed adjutant general of the New Brunswick Militia. He was instrumental in drafting the Militia Act of 1865 and was a strong advocate for the establishment of camps of instruction. He was highly regarded as an experienced professional soldier. Within a day of his appointment, the St. Andrews Standard reported “We learn that our respected friend, Lt. Col. Anderson will visit this country for the purpose of placing the Militia in an effective state — may be on a war footing. The Colonel is so well adapted for the duty, not only from his professional knowledge and experience, but also from his great popularity, that we augur much good from his visit. He will be well received by the officers and men of the Volunteers and Militia.”

The written instructions provided to Anderson gave him extraordinary scope and authority, a reflection of Gordon’s confidence in him. All four battalions of the Charlotte County Militia and the two battalions of the Carleton County Militia were placed under his command. Colonel Foster was directed to place at his disposal any 3-pounder guns that he might request. The quartermaster general was directed to fill all Anderson’s requisitions for arms and ammunition. Upon receiving his instructions, he was ordered to leave the next day for Saint John and Campobello. In Saint John, he was to “take an opportunity of communicating fully with Colonel Cole,” his immediate military superior. The instruction further directed that “Colonel Anderson will report with as little delay as possible the nature of the steps which in his opinion would be best calculated to prevent the landing of a small hostile force in Campobello or St. Andrews & their occupation of those points. Whilst waiting for instructions on this report he will proceed to carry out his views so far as the resources at his disposal permit.” Finally, Anderson was to report directly to the lieutenant-governor and “to do so frequently and fully.” Anderson’s appointment as district commander inspired confidence just when it was most needed, and he had the authority to act decisively. On March 17, the Saint Croix Courier reported “The militia force along the frontier has been placed under his command. The country is safe.”

As ordered, Anderson met with Cole in Saint John and then took the steamer New Brunswick on its regular run to Eastport, arriving on March 15. From there he made his way to Campobello where he remained for over a week, delayed by both illness and the weather. The militia on the Passamaquoddy islands formed the 3rd Battalion Charlotte County Militia, with its headquarters on Deer Island, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James Brown. The senior militia-man on Campobello Island was Captain Robinson. Defence measures on the island had begun prior to the arrival of Anderson. A volunteer rifle company had been formed under command of Captain Luke Bryon. This Class A company usually drilled twice weekly, but during the week of March 16, it drilled daily under the recently promoted Captain John Farmer, the battalion adjutant. A guard consisting of a sergeant and seven privates stood to nightly. Anderson found the guard armed, but without ammunition. He immediately sent his aide D’Arcy to procure a supply from St. Andrews. When he returned a couple of days later with a “keg of ammunition,” the volunteers began firing practice on the rifle range. Permission was granted to call out Captain Bryon’s company effective March 21. A request was made for twenty more rifles, as there were volunteers ready to carry them. In his report to Gordon, Anderson commented favourably on the excellent conduct of the volunteer company and singled out Sergeant Templeton for his zeal in command of the night guard. Steps were also taken to organize two volunteer companies on Deer Island under command of Captains Grew and Lloyd. Colonel Anderson noted that these protective measures and his visit had calmed public fear of a Fenian invasion, which had earlier lead to some families fleeing Campobello. In a confidential letter to Gordon, Anderson praised Captain Robinson for his professional assistance, local knowledge and hospitality. Anderson’s greatest concern was the lack of direct communication between St. Andrews and Campobello. If Campobello was attacked, it would take time for the information to reach St. Andrews and to provide assistance to the island.

Meanwhile, the citizens of St. Andrews were in a great state of alarm and some families were preparing to leave. The March 14 issue of the St. Andrews Standard noted, “Up to the present we confess very little has been accomplished. Men are ready to volunteer, provided they have rifles and ammunition.” When D’Arcy returned to Campobello, he gave Anderson an unsettling account of the situation in the town. Anderson reacted by warning Colonel Inches in St. Stephen to be prepared to come to the assistance of St. Andrews and gave serious consideration to bringing in the Fredericton artillery battery with their two 6-pounders. Anderson telegraphed Gordon from Campobello requesting permission to embody Captain Pheasant’s company and Captain Osborne’s artillery battery, if necessary. He was reluctant to embody the battery because it was composed mainly of men employed on the railway and calling them out could adversely affect railway operations just at the time when they would be most needed.

Another key appointment made by the commander-in-chief was the selection of Major Cuthbert Willis as Commandant of St. Andrews with the local rank of lieutenant colonel. After Willis retired from the 15th Regiment, he was employed as the brigade major at the 1865 Camp of Instruction and was the inspecting officer of the Eastern District. The St. Andrews Standard was delighted with Willis’ selection and announced that the ranks of the home guard would be filled without delay now that there was “an assurance that they will not be compelled to serve under Col. Boyd.” The newspaper followed with disparaging remarks about “poor gallant Col. Boyd!” Not surprisingly, Boyd was not pleased with either Willis’ appointment or the public response. He attempted a rebuttal on the floor of the legislative assembly. He claimed that he was a popular officer within his battalion and that the lieutenant-governor had asked him to take command first, but that his legislative duties precluded it. Boyd’s protestations only sparked further derisive comments. A letter to the editor signed by “One of the Minions” said that Boyd’s rebuttal was “a piece of egoism on his part rarely surpassed” and went on to question how Boyd could have the gall to remain in office, having had his advice ignored and passed over for command. Anderson confirmed publicly that Willis commanded the 1st Battalion Charlotte County Militia; however, he found it necessary to “send for the editor and caution him” about his libelous comments concerning Boyd. Colonel Willis set out immediately for St. Andrews to assume his new appointment. When questioned by the home guard, Willis explained that he was there only temporarily and that he could not guarantee that Boyd would not command again. Boyd was a man who knew how to carry a grudge. Later, when asked to contribute to the Victoria Day celebrations in St. Andrews, he refused. As reported in the Saint Croix Courier “Col James Boyd refused to subscribe a cent to buy gunpowder for firing a salute on the Queen’s birthday. This the same Mr. Boyd who is at present soliciting the vote of the loyal electors of Charlotte county for a seat in the House of Assembly.” Despite the stress it caused Boyd, it appeared Gordon had made a wise choice in selecting Willis.

The arrival of Colonel Willis in St. Andrews was well received by the St. Andrews Standard. It proclaimed, “There appears at last a spark of life in the Militia authorities.” Willis took charge immediately. He found that Captain Pheasant’s Gordon Rifles drilled regularly under Drill Instructor Sergeant Quinn and Captain Osborne’s artillery battery mounted guard nightly. On March 21 the Gordon Rifles were embodied with the strength of three officers, three sergeants, two corporals, one bugler and twenty-six privates. They commenced garrison duties immediately. Willis established an outpost at Joe’s Point Blockhouse, consisting of a sergeant, corporal and six men. This old blockhouse from the War of 1812 was located on the St. Croix River a mile from St. Andrews, opposite Robbinston, Maine, overlooking the river and the Maine border. The sergeant could raise an alarm by flying a “danger flag” by day or by dispatching a mounted messenger by night. A sergeant and six gunners from Osborne’s battery were also embodied and stationed in Fort Tipperary, an old fortification dating from 1808, located at the edge of town. The home guard was reconstituted, and Captain James was appointed major of the guard. The guard was divided into two companies, each under the command of a captain and a subaltern. Noncommissioned officers were assigned and drill was conducted four times a week under qualified drill instructors. Eighty-three men volunteered for service, and within a week they provided a piquet of one sergeant and six privates to stand guard over the arms stored at the Town Hall.

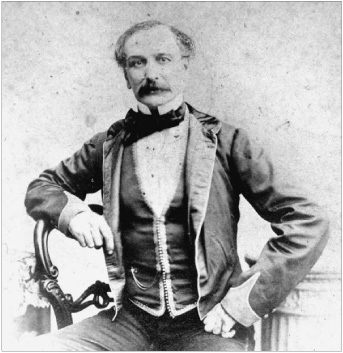

Believed to be the Gordon Rifles, the St. Andrews Class A Volunteer militia company under the command of Captain Benjamin R. Stephenson, circa 1866. Courtesy of Charlotte County Archives P69-436

When Anderson arrived in St. Andrews from Campobello, he approved all the actions taken by Willis. In addition, he had a 9-pounder cannon put into working order and placed in Market Square where it could sweep the approaches along the streets in three directions. Although he had managed to obtain several rounds of cannister, he confessed it was mainly for show, as he doubted the old cannon could be fired more than once. Anderson and Willis set out together to inspect all the outposts around the town but were hindered by the heaviest snowfall of the winter, which had been plaguing the region for several days. Although the St. Andrews Standard reported “there are now excellent traveling” conditions, they became stuck in a snowdrift and broke the traces on their sled. In a confidential report to Gordon, Anderson informed him that Major James had been “most active and zealous … as he is a man of property his presence here is worth a good deal at present.” He believed that James owned half the town by mortgage and requested permission to “retain him at any price.” On March 27, Anderson was able to report with satisfaction that the people of St. Andrews seemed to be over their fright. This view was supported next day in the St. Andrews Standard, which stated, “The military ardor of the inhabitants cannot be excelled. Capt Pheasant’s company are doing garrison duty, in martial style. Red coats in the streets are quite refreshing and the uniforms in the churches on Sabbath last, gave proof that loyalty was at a premium.” The newspaper knew where to place the credit: “In fact everything is being done in a systematic and military style, which goes to prove the wisdom of Col. Anderson’s appointment, and his ability, energy and popularity.”

On March 28, Anderson reported to Gordon that there was a Fenian spy in St. Andrews. According to Anderson, David Barry, an American citizen, had arrived in town from Eastport and made inquiries about local defence arrangements. At one point, he bragged that he was a Fenian and that they would soon invade and he would be among them. Although uncertain about his civil powers, Anderson ordered Colonel Willis to arrest him. Once he was turned over to the civil authorities, Barry was soon released by the attorney general. The Eastport Sentinel was incensed by his arrest and reported quite a different story. According to the Sentinel, Barry, who was from Concord, New Hampshire, had returned to Eastport to close his business and visit old friends after having moved away. While visiting and having dinner in St. Andrews, “the subject of a Fenian invasion was discussed, and Mr. Barry in reply to a question expressed the opinion that 60,000 Fenians could take the Canadas. Soon after dinner Mr. Barry was arrested and brought before a Justice Fitzgerald, who ordered him to be committed to jail on the charge of being guilty of treason.” Barry was lodged in “a filthy loathsome dungeon” in “a cell reserved for murderers,” denied bail, and released only after a lawyer was finally obtained.

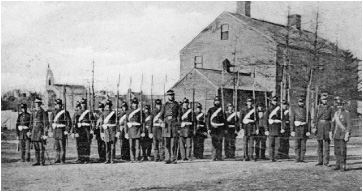

Joe’s Point Blockhouse overlooking the St. Croix River near St. Andrews. Built during the War of 1812 and used as an outpost during the Fenian crisis. PANB P23-20

Barry was not the first to be arrested for treason. Captain Robinson on Campobello Island arrested Hugh Muldoon of Eastport, formerly of Saint John. He too had been sent to St. Andrews, held in jail and then released. It was later determined that Muldoon was indeed a Fenian. Robinson maintained that there were other suspicious characters on the island and requested handcuffs be forwarded to him without delay. The ever energetic Anderson, not pleased with the reaction of the civil authorities, threatened to take matters into his own hands, if necessary, by taking a “clerk of the Peace out with me to read the Riot Act.”

With the defence of the Frontier District in the capable hands of Anderson, Colonel Cole concentrated his attention on the security of Saint John. His first concern was the safety of the arms and ammunition scattered in various locations around the city. The arms allotted to the militia were moved to a storage space under the Saint John Volunteer Battalion orderly room, which was manned twenty-four hours a day. It took several horse-drawn wagons a whole day to move the seventy-eight boxes of arms. The ammunition stored in the Carleton Martello Tower and at Fort Howe was moved to a secure location in town. Cole and his engineer officer made a thorough inspection of all the defensive positions around the city. He instructed the engineers to prepare the Martello tower for defence by removing the roof and mounting cannon. The volunteer artillery batteries occupied Reed’s Point Battery and established sentry posts at what was later known as Fort Dufferin and at Sand Cove. Fifty artillerymen from Captain Pick’s battery boarded a tug and landed on Partridge Island, along with a supply of arms, ammunition, stoves, bedding, baggage and provisions. Unfortunately, the engineer work necessary to complete these tasks was delayed by severe winter weather, which, Cole noted, was “too boisterous to work.”

Fort Tipperary, St. Andrews built in 1808 during the Napoleonic Wars. PANB

On March 19, Cole inspected the Saint John Volunteer Battalion and reported 206 effective men and 186 recruits on parade. The battalion commenced daily drills lasting five to six hours at the Reed’s Point Wharf. Because of the lack of accommodation, he accepted Colonel Otty’s recommendation that one hundred men be quartered in the barracks and the remainder be allowed to return home at night. To improve the administration of the Volunteer Battalion, Acting Major D. Wilson, a secretary to Gordon and captain in the York Volunteers, was selected to temporarily replace Major Charles R. Ray, who was absent on leave in England. The Volunteer Battalion was ordered to conduct patrols in the city and establish an outpost at Musquash, consisting of a sergeant and eight privates. This outpost covered the land approach to the city from the west and was positioned to give early warning of an attack.

Carleton Martello Tower seen from an adjacent hill showing the battery position built during the Fenian crisis. NBM 1956-43-11

Cole informed the lieutenant-governor that the public remained fearful and that some people’s actions were “ludicrous.” For example, a family at Red Head never lit a candle at night for fear of drawing cannon fire from a marauding Fenian ship, and “some Ladies put 3 dresses on at night - so as to carry what is dear to them into the woods - in case of flight.” Cole believed the civil authorities needed strengthening in order to be ready to suppress any local unrest. When Police Magistrate Tapley requested twelve carbines, Cole replied that if arms could not be obtained from the militia quartermaster, he would provide them, but suggested pistols would be a better choice than carbines. To assess the situation for himself, Gordon arrived in Saint John on Friday, March 23, to spend the weekend. He stayed at the Stubb’s Hotel, where the volunteer battalion mounted guard for his protection. On Saturday, the lieutenant-governor reviewed the volunteer battalion at Barrack Green, where he gave a stirring address outlining the Fenian threat and explaining why the battalion had been called out on active service. However, not everyone agreed with the lieutenant-governor. On March 28, the Morning News said, “We are of opinion that the Government have done real harm, unmixed with the slightest gain of good, in their recent and ill-timed mandate, calling out the Volunteers. The effect has been to take men away from their avocations, and thus cripple shipyards, foundries and mills in the commencement of the season.”

Considering that it was only at the end of December 1865 that the lieutenant-governor started taking measures to protect against the Fenians, a great deal had been accomplished in three months. An effective command structure was in place, government funding arranged and a thousand men of the provincial militia stood ready along the Maine border from Centreville in Carleton County, south to St. Andrews and along the Bay of Fundy to Saint John. Although there was much left to be done to increase the effectiveness of this provincial field force, New Brunswick was significantly more prepared for any Fenian action than it had been. To quote the Saint John Morning News in discussing the Fenian Brotherhood, “Let them come, if they dare.”