We are the Fenian Brotherhood, skilled in the arts of war,

And we’re going to fight for Ireland, the land that we adore.

Many battles we have won, along with the boys in blue,

And we’ll go and capture Canada, for we’ve nothing else to do.

— A popular Fenian song

After months of speeches, parades and donating their hard earned money to the cause, the membership of the Fenian Brotherhood clamoured for action. The O’Mahony wing of the Brotherhood had no option but to put its plans into motion. On St. Patrick’s Day 1866, the Fenian leadership approved Bernard Doran Killian’s proposal to invade Campobello Island in the belief that occupying a piece of British territory would give the Fenians a belligerent status under international law. They could then issue letters of marque and reprisal to privateers to prey on British shipping, purchase arms and ammunition freely, and raise an army without breaking any American laws or violating neutrality. Unfortunately for the enterprise, no attempt was made to keep the decision to invade Campobello a secret. Charles W. Beckwith of Fredericton was attending Harvard University in Boston when a former Frederictonian, Jack O’Brien, a Fenian leader, invited him to a rally. There the proposal to invade Campobello was openly discussed. Without delay, Beckwith forewarned New Brunswick authorities. As usual, British spies were omnipresent and also provided detailed reports.

Once Killian received approval, preparations were set in motion. Since sending an armed body of men to the Maine border would violate American law, it was decided that the men and the arms would travel separately. The Fenians hired the schooner Ocean Spray in New York and loaded it with military stores, including a consignment of Spencer rifles. Concurrently, the Fenian rank and file began making their way to the Maine border in small contingents taking separate routes. Although they frequently referred to themselves as “delegates,” they made little effort to conceal their identity, as most wore parts of uniform and almost all sported knives and revolvers.

In mid-March 1866, the Eastport Sentinel noted that “our New Brunswick neighbours along the line are greatly excited by the apprehension of an invasion by the Fenians. We are of the opinion that this organization which is causing so much excitement in this country and in England and Ireland, will strike a blow somewhere soon. The excitement cannot be sustained much longer without action.” On April 11, the Eastport Sentinel announced, “The Fenians are indeed among us.” A day earlier, Robert Ker, the British Vice Consul in Eastport, sent a telegram informing Colonel Willis in St. Andrews that one hundred unarmed Fenians had arrived and that their arms had been delayed in Portland by American authorities. The Saint John Morning News enlarged on this report stating, “There were many startling rumors about in City yesterday respecting movements of the Fenian banditti. It was said that upwards of two hundred armed men endeavored to take passage on board the American boat at Portland for Eastport, but were refused passage unless they left their arms behind them, and that a few men remained to superintend the transportation of the arms, while the others proceeded to, and landed at, Eastport.” Other reports warned that groups of Fenians were approaching Eastport from different directions, intending to make it the starting point for an attack on New Brunswick.

On April 10, General Killian and three aides arrived in Eastport by steamer where they spent the first couple of days securing financing from New York. Once funds became available, a series of mysterious and confusing activities occurred in and around Eastport: Colonel Favor’s swivel gun disappeared, but he later received payment for the weapon from persons unknown; reports circulated that the nearby Pembroke Iron Works had been contracted to recast several old cannons; three large kegs of powder were purchased and men were set to work making cartridges; Killian rented Trescott Hall in Eastport for a convention, which also became his headquarters; Vice Consul Ker telegraphed Colonel Anderson that two schooners had been engaged, one to sail to Lubec for arms and the other to go to Machias. The stories and rumours circulating about the Fenians were so confusing that David Main, the editor of the Saint Croix Courier in St. Stephen, went to Eastport to obtain first-hand information and checked into the hotel where the Fenian leaders were staying. Breakfast there provided an excellent opportunity to observe the “enemy.” He described Killian as “a fine portly looking fellow, broad open countenance, but with rather a sinister expression of the eye. He is accompanied by two secretaries, one of whom is a genteel, modest looking individual with no particular distinguishing features, the other one named McDermott is a rough Irish lad, evidently lacking in brains, judgment and experience, as quiet as a mouse in the presence of his master, but garrulous and bombastic when the latter is out of sight.”

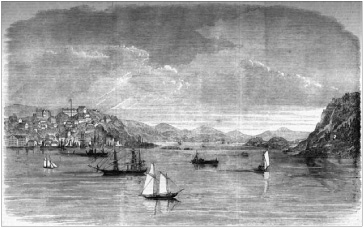

“Eastport, Maine The Rendezvous of the Fenians in the United States.” Illustrated London News, 5 May 1866. New Brunswick Museum

The Fenians continued to arrive in Eastport and along the St. Croix River by boat, stagecoach and on foot. While awaiting the arrival of their arms, they drilled on the sandy beach near Dog Island at Eastport and at Robbinston on the St. Croix River without any interference from American authorities. Because they moved in small groups and never concentrated, it was difficult to determine precisely how many Fenians appeared in Maine; however, at peak strength it is believed they numbered about one thousand. Vice Consul Ker estimated four hundred in Eastport, four hundred in Calais and another two hundred scattered between Lubec, Pembroke and Robbinston.

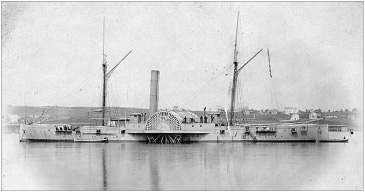

Not surprisingly, the arrival of the Fenians increased tension in New Brunswick; it also created considerable apprehension on the Maine side of the border. Washington Long, Collector of Customs in Eastport, telegraphed the Treasury Department to urgently request an experienced officer be sent to take command. On the same day, Lieutenant-Governor Gordon telegraphed Secretary of State William Seward, informing him of the imminent arrival of the Ocean Spray loaded with arms. The American government’s concern grew, both for the safety of their citizens facing armed strangers roaming their communities and for the threat posed to their neutrality. This pressure forced Washington to abandon its complacent and ambivalent attitude toward the Fenian Brotherhood. Commissioner L. G. Downes and Deputy Marshal B. F. Farrar were sent to Eastport to ensure that the neutrality of the United States was not compromised. Seward notified Attorney General James Speed of the situation along the Maine border and requested he take appropriate action. The United States Navy formed a strong squadron for duty in eastern waters under the command of Acting Rear Admiral Boggs, consisting of the 9-gun side-wheel steamer USS De Soto, the 4-gun double-ender ironclad USS Mantonomak, the 7-gun side-wheel steamer USS Augusta, the 9-gun double-ender USS Winooski and the 7-gun USS Don. This Eastern Squadron was ordered to rendezvous at Eastport by April 30 and remain until the “Fenian excitement” had abated. In response to Collector Long’s request, the Secretary of War ordered Major General George Gordon Meade, the hero of the Battle of Gettysburg, to Eastport.

USS Winooski. Built in Boston and commissioned in June 1865. She was employed in Maine waters during the Fenian crisis, where three of her crew won the Congressional Medal of Honour for bravery while saving two sailors from drowning. Courtesy of U.S. Naval Historical Center NH 43863

Meanwhile, Fenian activity continued to increase along the border. The steamer SS Queen landed thirty to forty Fenians wearing sidearms at Robbinston. The other passengers on the steamer quoted the Fenians as saying that they intended to take possession of the province, raise their flag and proclaim an Irish Republic. In the dead of night, on Friday, April 13, two boatloads of men led by Dennis Doyle, the head of the Fenian circle in Calais, crossed the St. Croix River. They landed at Porter’s Farm, just below St. Stephen, and were spotted by “Old Joe” Young, a well-known local character. Not unlike the famous Paul Revere, Young jumped upon his horse to spread the alarm. The thundering of hooves, the pounding on doors and the shouting of “Arm yourselves! The Fenians are upon you!” would be long remembered by the local residents. Doyle and his men contented themselves with firing a few shots in the air, setting fire to some woodpiles and returning to Maine. However, this demonstration was sufficient to frighten some residents into packing up their valuables, closing up their homes and fleeing. On the following night, Saturday, April 14, the infamous Indian Island “flag incident” occurred. As reported in the Saint John Morning Freeman, several strange and unusual happenings took place that day, “About 9 o’clock … a steamer of strange appearance passed by here [Eastport] from the Eastern passage. She came up slowly until about opposite the town, and then run up a green and red light, in place of the white one which she carried. This done, she passed on towards Lubec, anchoring opposite Friar’s Head, Campobello. She stopped there about an hour and a half, and then proceeded seaward past Lubec.” At about midnight, nine armed men debarked from the “steamer of strange appearance” and rowed ashore with muffled oars. They demanded at gun point that Customs Collector Dixon surrender his Union Jack. On the same night, another unusual incident occurred off Partridge Island in Saint John Harbour. At about ten o’clock in the evening, a “bright white flash [sic] Light was shown in the Eastern Channel about half way up the Island.” Captain Pick reported that neither he nor any of the sentries could discern a ship, but that the light moved quickly around the island, flashed at intervals, disappeared and then reappeared again at midnight. The Partridge Island detachment firmly believed it was a small Fenian steamer conducting a reconnaissance. The ever vigilant Vice Consul Ker had heard that a small British schooner had been purchased in Eastport, and his suspicions were further aroused when some of the Fenians leaders were seen onboard. These events increased the speculation and uncertainty.

The long awaited Ocean Spray docked in Eastport on April 17, with the 129 cases of arms onboard consigned to Colonel James Kerrigan, one of Killian’s lieutenants. On orders from Customs Collector Long, it was immediately detained by the captain of the revenue cutter USS Ashuelot. Long telegraphed the district attorney in Portland asking for further instructions. The district attorney informed Long that there were no grounds for seizure of either the vessel or arms, unless he had evidence the arms were destined for foreign territory. The Fenians may have pulled strings, leaving Long with no choice but to release the Ocean Spray and its cargo. However, to the chagrin of the Fenians, USS Winooski arrived in harbour. Its captain seized the initiative and impounded the ship and arms again, then sought direction from the secretary of the navy. Vice Consul Ker telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington requesting his intervention with the American government. He then visited Commander Cooper, the captain of the Winooski, to elicit his cooperation in keeping the weapons out of Fenian hands. Cooper’s telegram created a serious dilemma for government officials, who had to uphold American neutrality but did not want to appear too direct as the mid-term congressional elections were fast approaching and the Irish vote remained an important consideration. No one in government was willing to commit himself. While they dithered, secretary of the treasury, Hugh McCullough, instructed Long to detain the ship and arms until further notice. The next day, General Meade arrived in Eastport. After consultation with Long, the arms were removed from the Ocean Spray and deposited in Eastport’s Fort Sullivan for safekeeping. In the process of unloading, it was learned that seven cases of rifles had disappeared. The Fenians were perplexed by this turn of events and felt betrayed by the United States government. Ker later reported that Ocean Spray’s cargo contained more than six hundred stands of arms, 197,000 rounds of ammunition and several coehorns. Although not obvious at the time, the seizure of Ocean Spray’s cargo of arms ended any possibility of a large-scale Fenian invasion of New Brunswick.

While the events surrounding the Ocean Spray were unfolding, the Fenians remained active along the border. Placards had been placed announcing a Fenian rally on April 16 in the St. Croix Hall in Calais. It was attended by a thousand people and addressed by Killian and his former New Brunswick lieutenant, Patrick A. Sinnott. Both disclaimed any intent to invade New Brunswick and confirmed that American laws would be respected. They claimed that 150,000 Irishmen had given their lives in the Civil War and that the United States owed a debt of gratitude that could be settled by supporting the Fenian Brotherhood in their goal of freeing Ireland. They announced that they would not allow Great Britain to “force” Confederation on the provinces and that the Fenian “convention” intended to remain on the border until the Confederation issue had been settled. Out of curiosity, some ladies from St. Stephen attended and reported that Killian had a “pleasant voice and a smooth fluent way of speaking.” The audience was attentive but not enthusiastic.

Killian and his party remained in Calais for several days, and they took the opportunity to stroll across the international bridge to St. Stephen. Much to the annoyance of Colonel Inches, nothing could be done to stop them as long as they remained peaceful. Not to be outdone, some of the militiamen crossed over into Calais in their scarlet uniforms. These visits led to heated discussions and, on more than one occasion, fist fights followed with both sides claiming victory. To keep nerves on edge, Doyle, the Calais Fenian leader, had woodpiles built along the St. Croix River from the lower wharf in Calais to Milltown four miles away. One night, on a signal, the bonfires were set alight and guns fired. Panic ensued, and many in St. Stephen, fearing the invasion had started, fled their homes.

In Eastport on April 28, about fifty men under command of a Colonel Kelly boarded the British-owned schooner Two Friends. Captain Corson and his vessel had been hired earlier by Killian at ten dollars a day to be ready at a moment’s notice to transport men and supplies. When Corson saw his passengers had several cases of rifles, he refused to move. At gun point, he was ordered to sail for Campobello. On the way past Lubec, the Two Friends was becalmed, and Mr. Harmon, the deputy collector of customs, managed to board the vessel. When he found armed men onboard, he quickly returned to Lubec and sounded the alert. Admiral Boggs ordered a couple of ships in pursuit. Before the American warships could sail, the Two Friends got under way, rounded a point of land and disappeared. At that moment, the schooner Wentworth from Windsor, Nova Scotia, under command of Captain McBlume, hove into sight. The Fenians forced Captain Corson to pull alongside the unsuspecting Wentworth so that she could be boarded and seized. When everyone was safely transferred to the Wentworth, the Two Friends was scuttled. When the pursuers finally approached, they were blithely told their quarry was around the next point of land. USS Winooski cruised the area for a day but found nothing. The Fenians sailed back to Eastport, disembarked and discarded their ammunition, which was recovered later by local residents. Captain McBlume reported that the Fenians acted in an orderly manner and did no damage to his ship or crew. After the Fenians had left, the captain resumed command of his ship and proceeded on his voyage to New York. These acts of terrorism, however, could not be ignored by the authorities in either New Brunswick or Great Britain.

St. Croix River waterfront at Calais, Maine. PANB P11-109

“HMS Rosario overhauling the Slaver Carl” in 1871. The Rosario exemplified the world-wide commitment of the Royal Navy. It helped end a rebellion in Jamaica in 1865, participated in the Fenian crisis in 1866 and then sailed to the South Pacific to suppress the slave trade. Courtesy of National Library of Australia