A Boston newspaper article dated April 23, 1866, reported, “The threatened Fenian invasion of the eastern Provinces has bursted and most of those composing the expedition have left Eastport.” Nevertheless, on the same day, Vice Consul Ker reported that “Fenian excitement here [Eastport] is still high, alto(sic) somewhat abated since last week,” and the number of Fenians in town had increased, as they “keep going & coming in squads of 10 or 20.” The threat of an invasion may have dissipated, but the Fenians still had the capacity for mischief. A series of incidents occurred in late April and May that kept the border inflamed and the defence forces alert.

The arrival of the Halifax Field Force required a major adjustment by both the local communities and the defence forces. The Carleton Sentinel reported “Our sister town St. Andrews is all life and bustle. The red coats of the army and the blue of the navy have created a lively appearance.” The editor then coyly noted that, in addition to providing a great sense of security, “the jingle of the silver incident to the sustenance of the army and navy has had, of course, a soothing and salutary effect on the nerves of the system which connect with the purse.” It was described as “the gayest summer ever known in St. Andrews with the town full of delightful young officers and ships of war patrolling the St. Croix.” With British regulars in St. Andrews, there was no need for the continued presence of the forty-one men of the Victoria Rifles from Fredericton. When they had been despatched, the Fredericton Headquarters had expressed the hope that “there will be no need for our Volunteers to show their courage — should there be, we have no doubt about their proving it.” Although they saw no action, they acquitted themselves admirably, and the local newspaper reported that “their conduct created a most favourable impression on the minds of the inhabitants,” which was reciprocated with hospitality and kindness. Before their departure and in appreciation for their service, the Victoria Rifles were entertained at “an excellent” public dinner held in the St. Andrews Town Hall. Their return trip home on April 27 was much more enjoyable than the one to St. Andrews; Major Simond and his men travelled by railway to Woodstock and then by steamer down the St. John River to Fredericton. On the way through Woodstock, Colonel Baird greeted them with a letter of commendation from Colonel Anderson and the information that they were released from active service. Two days later, Charles Moffitt recorded in his diary that the volunteers in his employ were back to work in his shop.

On Sunday, 22 April, All Saints Anglican Church in St. Andrews held a special service for the garrison, at which the pews were filled to capacity. In addition, all the regular morning services in town were well attended by the military, in particular the Established Church of Scotland. The view of the town’s people was expressed in the St. Andrews Standard, “It affords us much pleasure to state that the soldiers stationed in this garrison, Regulars and Volunteers, are of the right stuff and that their conduct since their arrival has been unexceptional.” In appreciation for the town’s hospitality, “the splendid Band of the 17th Regiment” gave concerts in the Court House Square twice weekly, in addition to a special concert held in aid of the building fund for a new church in town.

On April 23, Captain Robert Gibson of HMS Duncan hosted local dignitaries from both sides of the border onboard ship. They included the editor of the Saint Croix Courier, who wrote a glowing, detailed account of the impressive Duncan, its crew and weaponry. He also noted that many of the ship’s officers were absent on a fishing expedition, while Admiral Hope had taken the opportunity for some sightseeing. Hope and his aide had travelled to Woodstock by train and booked into the Blanchard House. The next day, Hope visited the iron works in Upper Woodstock and lunched at the home of the Honourable Charles Connell, returning to St. Andrews on the evening train.

Because St. Stephen was vulnerable to Fenian incursions, consideration was given to reinforcing the town’s garrison with British regulars. However, Doyle remained concerned about desertion by troops stationed so close to the American border. When Colonel Anderson implied that reinforcements might not come, Inches wrote to Gordon on April 18 to plead his case, explaining that “the people here have felt much better since they heard there were troops coming … & the disappointment should they not come here, will be keenly felt.” Immediately after the landing of the Halifax Field Force, Gordon, Doyle and Hope sailed to St. Stephen to assess the situation. After seeing the large number of bridges across the St. Croix River and its narrow width, Doyle informed the Secretary of State for War in London that “nothing would have induced me to put Troops there except the urgent demand of the Lieut Governor and his assurance to me that the Local Force and Inhabitants generally would use every exertion to check desertion.” Doyle reluctantly agreed to position 150 regulars in St. Stephen.

Within a week, the agricultural society building had been adapted to accommodate 180 men and four new buildings were erected for a cook-house, wash room, guardhouse, orderly room and commissary. William Buchanan’s stone house was deemed suitable quarters for the officers. On May 3, after several delays, three companies from the 2nd Battalion, 17th Regiment, totalling 150 men, under the command of Major Clement Heigham, sailed up the St. Croix River in HMS Fawn and a schooner. Accompanying them were two 6-pounder cannons and one 12-pounder howitzer in the charge of Captain Newman of the Royal Artillery, to be delivered to the recently formed St. Stephen Artillery Battery. Once established in their new quarters on the agricultural grounds, the soldiers were treated to a feast provided by local ladies. More than 250 sat down to dinner, and among the many guests were Colonel Henry and Lieutenant Wheeler from the United States Army post in Calais. In thanking the citizens of St. Stephen for their warm welcome and the ladies for the wonderful banquet, Doyle displayed his Irish charm saying, “the fair ladies of St. Stephen had done what he hoped the ‘Finnegans’ never would be permitted to do — take a British General very much by surprise.” The detachment of the 17th Regiment stayed in St. Stephen for a week, training and drilling with the local volunteers.

On April 23, an event occurred on the Ferry Point Bridge over the St. Croix River that created an international stir. Privates John Winder and Thomas Hanson of the St. Stephen Rifles were on bridge guard when two men approaching from Calais were identified as Fenians. They were refused entry, and in the heated exchange that followed one of the men said, “we will meet you soon again at the point of the bayonet.” While withdrawing, one of the Fenians suddenly drew a pistol and fired at Hanson, but missed. The United States Army guard at the Calais end of the bridge promptly arrested the two Fenians and handed them over to civil authorities. Next day, they were found guilty of drunkenness, fined and released. Under pressure, Governor Samuel Cony of Maine ordered them rearrested. Gordon was considering extradition but a jurisdictional wrangle ensued over the precise point on the bridge from which the shot was fired. Once it was determined that the Fenian had fired from the Maine side of the bridge, jurisdiction fell to Cony. Eventually, the two miscreants were quietly released; however, the incident created sufficient apprehension that USS De Soto with 350 American soldiers onboard was despatched to Eastport.

An Eastport resident named Burns had been very helpful to Vice Consul Ker by providing intelligence and assistance. His actions made him very unpopular with the Fenian Brotherhood. One evening, Burns told Ker that he had been threatened and he feared that his property on Indian Island would be destroyed later that night. Knowing firsthand about Fenian terror tactics, Ker contacted Captain Robinson on Campobello in an attempt to obtain protection for Burns’ property. The captain of HMS Pylades, who was in the area, was also approached. To Ker’s great disappointment nothing could be done. On Saturday, April 21, raiders landed on Indian Island and burned four warehouses “to the water’s edge.” One was a bonded warehouse containing a large consignment of liquor awaiting payment of duties. All the destroyed property, including Burns’s, was American owned. In a telegram to the lieutenant-governor, Ker reported the loss as valued at the substantial sum of eight to ten thousand dollars. The Fenians had their revenge.

The Indian Island school house which was fortified as a military outpost during the Fenian crisis. Its strategic position is evident; overlooking Marble Island, Cherry Island to the left and Campobello Island in the distance. PANB P8-300

Although he considered Captain Hood of HMS Pylades “a very zealous & diligent officer,” Admiral Hope felt “obliged to censure him for not having taken sufficient measures to prevent” the burning of the warehouses. The day after the raid Hope, Doyle and Hood visited Indian Island and concluded that a military post should be established there. After consultation with James Dixon, the customs officer, a recently built but unused school house was selected for a fortified post. Under the direction of a Royal Engineer officer, men from HMS Rosario built a palisade around the school, raised an earth embarkment to the window level and sandbagged and loopholed the windows. Initially, one officer and twenty-five sailors formed the garrison until they were replaced by the army. By May 3, Ensign Robert P. Chandler, Sergeant W. Whitlock and nineteen privates from the St. Andrews garrison had relieved the sailors of their post.

A key factor in reducing the tension along the border was the close relationship that existed between Generals Doyle and Meade. For three months, Doyle had been Meade’s guest when he commanded the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. A close friendship based on mutual respect had developed, and they were delighted to find themselves both serving on the Maine border. On April 19, when Meade was in Calais, Doyle paid him a visit, during which they talked at length. Doyle invited Meade to accompany him on his inspection of the St. Stephen Rifles. On May 1, Meade reciprocated by sailing to St. Andrews in the steamer Regular. Unfortunately, Meade had developed a bad cold which threatened to become pneumonia and was too ill to leave the ship. The St. Andrews Standard reported that the visit onboard “lasted for some time; and on parting, at the insistence of Gen Doyle the band of the 17th Regt, struck up the tune ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot’.” Soon after, Meade returned to Philadelphia.

On May 7, Doyle reported that the Fenians were “gradually dispersing.” As a result, and with the concurrence of Gordon, he planned to withdraw the Halifax Field Force and replace it with the Saint John Volunteer Battalion in St. Andrews and two companies of the 15th Regiment in St. Stephen. In order to free up accommodation in Halifax, he proposed releasing the 2nd Battalion, 16th Regiment, and permitting it to proceed with its planned rotation to Barbados. After five winters in North America, he was anxious that the battalion reach the West Indies before the hot season, so the soldiers could acclimatize. However, he was adamant that the British forces stationed in New Brunswick should not be reduced because the “local controversy on the subject of Confederation induces the Fenian Leaders to turn their special attention to New Brunswick in the hope of gaining at least sympathy from those most [sic] residents opposed to the Plans of Government.” Doyle also noted that “the Spirit of the Volunteers, and the zeal with which they have turned out is most praiseworthy, still they need cohesion, and the confidence of support derived from the presence of Regular Troops.”

In accordance with Doyle’s plan, Colonel Otty received orders on May 8 to prepare his battalion for embarkation to St. Andrews. A similar order was issued to two companies of the 15th Regiment; however, shortly afterward it was rescinded. On May 10, the Saint John Volunteer Battalion marched up Prince William Street from Reed’s Point to the Ferry Boat Wharf, led by Otty on horseback and the band of the 15th Regiment. Watched by a crowd estimated at two thousand, the band played “in a masterly manner that appropriate air ‘Thou art far away, far away from poor Janette’.” The battalion sailed that evening onboard HMS Simoon. They disembarked the next morning and occupied the temporary barracks just vacated by the 17th Regiment, while the British regulars occupied the recently emptied berths on HMS Simoon. The townspeople of both St. Andrews and St. Stephen regretted seeing the departure of the Halifax Field Force, and as the St. Andrews Standard recorded, “during the very brief sojourn of the troops here, they won the respect and good will of the people, which is not surprising; as their good conduct, and kindly feelings would make them favorites anywhere.”

Doyle’s anxiety concerning desertion by British regular soldiers was well founded. A James Burns was caught trying to assist two privates from the 17th Regiment to desert. He was sentenced to twelve months hard labour in the penitentiary, and the soldiers were returned to their regiment for trial. Privates Carroll and Donnelly of the 17th Regiment absconded from the St. Andrews garrison and after a week on the run they were apprehended by volunteers as they attempted to cross the Porter’s Mill Bridge at St. Stephen. When the 17th Regiment returned to Halifax, three of their deserters remained at large. When two soldiers of the 22nd Regiment deserted from the Fredericton garrison, one was captured sixty miles from the city, while the other made his escape. The captured deserter was sentenced to “fifty lashes and be transported for two years.”

With so many armed troops along the frontier, mishaps and misfortunes were not unknown. As part of their training the volunteer batteries in Saint John conducted a number of live-fire exercises with their cannon. As noted in the Morning News, not all were successful: “During the recent practice by the Volunteers at Dorchester Battery, the windows of the guard room were completely shattered and the building itself was much damaged.” Volunteers conducting rifle practice along the banks of St. Croix River had a ball ricochet off the water and nearly strike someone on the Calais side. As the Saint Croix Courier glibly remarked, “too great care cannot be exercised in the use of the rifle.” Two weeks after arriving in St. Andrews a private in Captain McShane’s company of the Saint John Volunteers died of natural causes and was buried with military honours. A sailor who broke his thigh bone falling from a mast on HMS Cordelia was reported “in a dangerous state.” Another sailor from the Cordelia suffered a bizarre accident. While visiting the Turnbull Sash Factory, he was watching with fascination the workings of the planer when suddenly “as if impelled to it in some way, he thrust his hand before the blade, and, in an instant, a portion of it was cut off.” Finally, the zeal displayed by the junior officers of HMS Fawn when their superiors were absent ashore caused international embarrassment. When they spotted a small boat heading for the Maine shore, they assumed it contained British deserters and fired across its bow. Unfortunately, it was an American pleasure craft containing young women and boys who did not understand the significance of the warning shot and promptly sped up. A second shot was fired directly at the boat. Following the good news and bad news scenario, the good news was that they missed, but the bad news was that the 10-pound shot fetched up a few feet from the door of a clergyman in Robbinston. Word was immediately sent to Eastport and USS De Soto was despatched to demand an explanation.

Continued Fenian activity along the St. Croix River kept Colonel Inches and his men alert and wary. On Sunday, May 20, a twelve-oared boat left Eastport for Calais. Inches maintained careful watch on the crew, passengers and cargo, noting that the gathering point was the home of Doyle, the leader of the Calais Fenians. When some of the passengers toured St. Stephen and its neighbourhood, their movements were closely surveilled. Noticing a stranger with a military bearing observing the St. Stephen Rifles at drill, Inches attempted to engage him in conversation, but when someone referred to Inches as “colonel,” the stranger beat a hasty retreat back across the border. When next day a second boat tied up to the first, Inches doubled the guard, made his men sleep with their boots on and he stayed alert all night. After the smaller boat mysteriously left and then returned, Inches and Captain Hutton rowed furtively over to personally check on it. A soldier from Captain Smith’s company, on his own initiative, spent a night hidden in a log pile on a Calais wharf, watching and listening, while Doyle and his men loaded a boat only feet from where he lay. These inexplicable Fenian activities maintained the tension along the border.

Ensign Chandler’s detachment on Indian Island was relieved by Lieutenant John B. Wilmot and seventeen men of the Saint John Volunteer Battalion. When Wilmot learned that the Fenians were threatening to raid the island again, he took the precaution of increasing the number of sentries from four to six. At last light on May 21, a sentry observed a boat pass Dog Island above Eastport and make its way to Cherry Island where it was joined by a second boat. About midnight, two boats with an estimated ten men in each, using muffled oars, made their way to Marble Island at the end of Indian Island. When challenged by the sentry, a shot was fired from one of the boats. The sentry returned fire and an exchange of shots quickly followed. Using a rocket, Lieutenant Wilmot immediately signalled HMS Niger, which was stationed off Campobello. Within twenty-five minutes, Niger responded with two boatloads of marines. With the volunteers on neighbouring Campobello also fully alerted, the Fenians fled into the night. The intent of the raiders was never made clear.

At about midnight on Wednesday, May 30, the citizens of St. Andrews were rudely disturbed from their slumbers “by the drums of HMS Cordelia beating to quarters, the firing of musketry, and the tramping of men and horses.” It was a calm but dark night, and it was not possible to discern the source of the disturbance. “In a few minutes a big gun from the Cordelia was discharged, and then another, which was promptly answered by one from the battery at Fort Tipperary, followed by the bugles at the Barracks sounding the assembly and the alarm, which led to a general rush to arms.” The town’s people feared the long awaited Fenian attack was underway. The Saint John Volunteers, Gordon Rifles, volunteer battery and home guard assembled immediately in accordance with their training. It was reported “that within five minutes the ammunition wagons were filled, the rifles strapped on, and the guns ready for action.” Although some volunteers had not taken the time to fully dress, they stood ready to face the foe. The sound of the heavy guns firing carried down the Bay of Fundy to St. George. It created a similar commotion there as the volunteers of St. George rushed to arms and manned their defences.

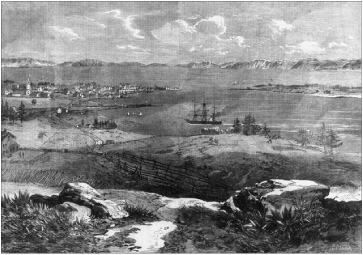

“St. Andrews Harbour and Bay, New Brunswick, 1862,” showing the town of St Andrews, the harbour, Navy Island and Passamaquoddy Bay from the area of Joe’s Point. PANB P4-3-62

Amidst the turmoil, people feared for their lives and the safety of their property. As the volunteers ran off to their battle stations, their families were left to fend for themselves. The wife of Corporal Levi Handy of the Gordon Rifles, alone and uncertain what to do, was terrified. She bundled up her children and hid them in the garden behind the house, after posting her fifteen year old son at the corner of their house with the family shotgun, instructing him to shoot on sight anyone approaching the yard. Luckily, it was daylight before Corporal Handy returned home.

During the pandemonium, Colonel Anderson displayed the leadership for which he was noted. He immediately dispatched an officer to ascertain the cause of the firing and within half an hour had the answer. It was a naval regulation that once a quarter every British warship was to practise repelling a surprise night assault using blank ammunition. Commander de Wahl of HMS Cordelia choose that night, while anchored snugly in the harbour of St. Andrews, to exercise his crew forgetting the tense atmosphere that existed in the town. The naval exercise was a success. It was “a minute and a half from the drums beating the men turned out and firing commenced.” Anderson quickly turned the awkward situation to his advantage by declaring it an unscheduled exercise. He was reported as saying “Commander de Wahl deserves the thanks of the people, for testing by his practice the courage of our Volunteers, they were up to the mark, and that in a very few minutes.” Everyone returned home extremely pleased with their performances and their displays of loyalty. Unfortunately, no one in St. Andrews was aware that the people of St. George were also on high alert, and it took some time before they got the word.

Throughout May, the Fenians along the border continued to disperse. Funding had run out, and many experienced difficulties paying rent and buying food. The American government offered free railway tickets to assist them on their way. The Carleton Sentinel reported on June 1 that “The First Regiment of Massachuset Fenians, numbering about eighty or one hundred men, has returned from the ‘Seat of War’ dispirited and demoralized. They are very bitter in their denunciations of the leaders; but expect to start again soon under more favorable auspices.” The aborted invasion left the O’Mahony faction of Fenian Brotherhood in disarray. Killian was blamed for the failed military venture and expelled from the movement. O’Mahony’s treasury had been depleted, and he was forced to resign. His wing of the Brotherhood eventually disintegrated. This failure on the Maine border permitted the Robert’s faction to take control and forge ahead with Sweeny’s invasion of Canada. A force of 850 Fenians crossed the Niagara River on May 31, raised the green flag and seized Fort Erie. They fought and won the Battle of Ridgeway on June 2. As the focus of the Fenian Brotherhood moved away from the New Brunswick border, affairs there gradually returned to normal. By mid-May, Gordon began reducing provincial defence expenditures. Selected volunteers were released from active service, the Saint John Volunteer Battalion returned to Saint John to great acclaim on June 1 and the post on Indian Island was abandoned on June 15. The last of the volunteers returned home on June 21, 1866. The Fenian crisis on the New Brunswick frontier was over.