It was spring of 2012 when I took my styling on the road. River was a year old at the time, and we lived in Bushwick, Brooklyn. A year prior, the weight of my hips felt too heavy at 145 pounds when riding in a livery cab on Wilson Avenue, my back contractions competing with potholes in the dead of winter. I was 121 pounds at six weeks or so when my pregnancy was confirmed by my gynecologist on Park Avenue in Clinton Hill, and I had been 117 pounds the last time I weighed myself in my first apartment on Saint James Place.

My favorite one-piece that I burned a hole through. It was airy and the bottoms of the pants swayed when I walked. I felt so proud to wear it that picture day in first grade. And, of course, with a matching scrunchie!

My life, for the most part, felt like it had been surrounded by loss already. Of equal importance, often a gain is swiftly couriered in before the weight of loss has time to settle. Trauma is shuffled to the back. Queue the bright lights! It is the story of my life and that of others who are often plagued with trauma but also have enormous privilege. Bringing that experience of what is lost and what is gained into my approach to styling for women felt like the only way.

While I didn’t have many clients when I first started out, the ones I had took energy and time and became intense and layered relationships. To go into a woman’s closet and touch things that hold stories, or to assess why she has fifteen pairs of shoes and only wears two, or why she hides a stack of size 4 jeans when she is a size 8, takes nerve and care. Normally, a client’s response would be a mix of concerns, confusion, and appreciation. My approach was to walk through it with them, and to reassure them that I am not doing something to them. I have learned that women tend to hold on to more than we need: clothes and people. I would always start every session by asking why. Why did they need me? What position of life were they in? What was the story they were trying to let go of? And who were they now? Doing that work while living through my own trauma was heavy.

The pieces of my own childhood outfits I wore and lost and the people who were there along the way are weaved into the threads of my clothes and my body. Thread by thread. Point by point. Like the outfit I wore in one of my favorite school photos: a red onesie with tiny white hearts printed all over. It had short sleeves and straight-leg pants. I lost that red one-piece when I attempted to iron it one morning. A cotton towel spread across my twin-size bed, my knees on the floor, the iron full of water. Turn on, heat up, switch to cotton, let it steam, then press down. A routine I’d known well. One morning the iron stuck—residual gunk from someone’s something or another. It was too hot and the gunk was too much and I burned the pants. A hole in the left leg, the edges of it brown and charred, and a deep gut sigh released itself from my tiny body. Nearly a decade later, in the summer of 2009, I found a similar red one-piece while thrifting at the Goodwill on Fulton Street. It had shorts and long sleeves and was just $2.99. I cut the crotch out of the shorts, making it into a skirt, and ripped the sleeves off. The bosom was large, but it was loose, and I belted it with a mustard belt with a tortoiseshell buckle—one of my grandmother’s, of course.

My father died soon after I thrifted that one-piece. It was the fall of 2009 when the air and leaves started to change, the unshakable respite from a sweltering Brooklyn summer and the distinct buzz of something new in the city air. I was staying with my mother in Bedford-Stuyvesant the morning we found out. I had gotten a message on Facebook from my cousin: “Hi LaTonya, I’m sorry to tell you this, but your dad died this morning.” She left her number and ended the message with her name. My mother and my father were married for fifteen years but had spent much of that time on and off. They were divorced when he died, and it had been the longest stretch I had gone without seeing him. Five years before, my mom read an email from him while standing at the thirty-minute computers in the library in Richmond, Virginia. His letter to her was long, and I stood beside her as she read it. All I remember seeing was his name, Franco, and the word cancer. The other words within the email blurred before my eyes.

Within a few weeks’ time, we were headed to Baltimore, Maryland, where my father was recovering from his surgery; inches of his intestines were removed to stop the cancer from spreading. The day we arrived, he wore a yellow T-shirt, a far cry from the deep blue button-up that my memory often places him wearing. The color of his skin, the wave of his short hair, and his dark pants always made him look like velvet. When we arrived, he didn’t look like he had cancer, or that he was recovering from a surgery. I remember his smile, how it lit up and how I thought he was so beautiful. Just beautiful. I don’t know of anyone who thinks their dad is beautiful, but he was. He lay down and I saw the scar reaching from the bottom of his belly up to his chest; it cut through his birthmark that matched mine. It was something that always connected us. He was in pain but alive and well. Optimistic and angry. My mom had packed us up and brought us to his side, so we all could be near him and she could care for him. Something she’d always do. I loved my father, but I hated being there. I loved my mother, but her desire to be loved by him in a way that was as temporary as it had always been made me resent her. The urgency of our visit, the lack of transparency on his part with his own family about my mother and about us, left tension so thick that our stay was my mother’s last straw. To this day, Baltimore is a hard city to visit. It was the last place I saw him alive.

We stopped at a Wendy’s on our way to Baltimore to visit my dad after the news of his diagnosis in 2013. I brought my camera, and my sister, Brittany, snapped this photo of me.

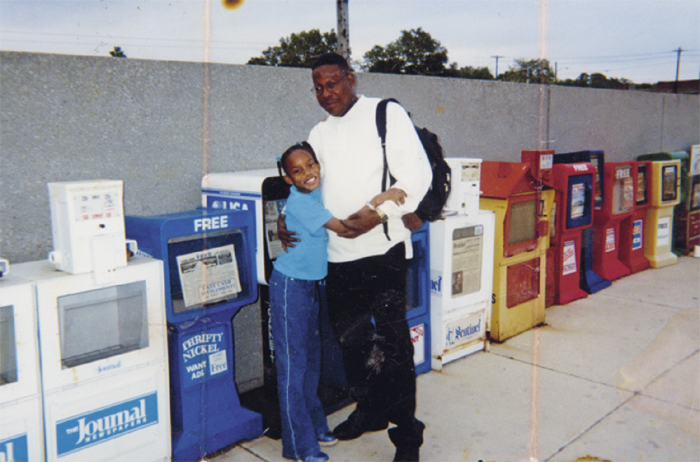

Me and my dad. This was taken when we went to visit him at his job. My mom matched my bo-bos to my top, and I wore these blue metallic sneakers/oxfords that had a slight heel. I was obsessed with them!

Throughout my childhood, my father spent many years in and out of contact with us; then one day he would show up with a court order for visitation. Then he would be gone again. One afternoon during one of the visits, he turned to me and said, “I don’t have to call, LaTonya. You can call me sometimes, too.” I was around ten. He was serious. I have spent the better part of my twenties coming to terms with the fact that I won’t ever fully understand my father’s mind. And in all honesty, I think my mom spent some of the same years accepting that she kept chasing his ghost. In his death, I suppose, he chose not to run. Just to hide. He talked to my mother weeks before he died. She asked him how he was doing; he asked to come visit her; she declined. They wished each other well, and he told her he loved her. A few weeks later she sent him pictures of my sister’s son, my brother’s son, and me with Peter. “A white boy! Of course,” he responded playfully.

He died weeks later. He knew he was dying when they talked and emailed. I made several calls the day he died, one to his own mother. By the time I reached her, the cremation process was just a few hours away. His memorial service, a day after. His mother laughed when I asked if my family could at least have his ashes. Collectively, we decided to skip his memorial. We weren’t welcome. Brooklyn felt like the real place to celebrate him. It was the place he and my mother met, where they were married, and where most of us were born. We drove to Coney Island and sat in the sand together. We dug our feet deep into the cold September sand, locked arms, told him we still loved him, and said farewell to our dad.

* * *

My grandmother was tiny and soft-spoken, and one of the very few times I saw her manner shift was in reference to my father. One summer, he had pushed hard and won visitation in court (which he only followed through with once, because he said we hated it), and my grandmother became a facilitator of the visit. I could sense the weight of his actions in that swift transition of us from her to him. That’s one of the very last times I saw their worlds cross before she passed away.

My grandmother on her birthday. This was typical. She got dressed up, wore a crown, and had her photo taken. The flowers were probably from my Uncle Ronnie. She wore the crown every single birthday.

When my grandmother died, my father called my sister to let her know how sorry he was, knowing how much she meant to her and my mother. To all of us.

My grandmother was my style icon. Every so often I stumble upon a picture from the eighties or nineties of my grandmother wearing clothes I received after she passed away. While her collection was far too large for us to keep everything, in the wake of her passing, I had the opportunity to sort through her clothes and take what I could. There were men’s vests and tulle skirts, a floral hatbox full of hats and scarves. There were some of the fanciest dresses I’ll ever own, that she’d wear on a very normal day. There were boots and loafers, and even a pair of leopard high-waisted pants that fit like leggings. I’ve worn most all of it since she died, stitching a piece of her memory not just into my closet, but into my everyday walk in life.

Truthfully, though my grandmother was my style inspiration, I don’t think I was the best granddaughter. I loved her and we talked, but I wasn’t a caregiver like my sister or mother. Once, during a routine physical therapy session, she and I bickered a bit because I refused to let her be dishonest with her doctor about how “good” she was doing. My grandmother was the type of woman who drank natural herbs in the morning, spent an hour in prayer, and slipped into a pair of mildly stretchy gold stylish flats, even when her foot was swollen and wrapped in an Ace bandage and she could barely walk. I was bossy, and her resistance to healing or figuring out the source of her issues bothered me. It made helping her frustrating. She was so young. Why didn’t she want the answers to live a more fulfilling life?

The morning she died, my mother called several times from her office, asking me to check on her. She was living on Jefferson Avenue, which was about a seven-minute bus ride from my mother’s apartment. It was my first day off from work in a while, and I was hesitant to visit her. My grandmother was caring for my cousin, my aunt’s son, full-time. When my mom had called earlier, he’d told my mother that my grandmother wouldn’t wake up.

When I entered her apartment, she was lying on her orange couch like she always had. Her long brown hair beside her face with a blanket over her. The TV in her view, her side table full of things, a hatbox in the corner, a vintage lamp on the antique nightstand in the window. My cousin jumped above her, planting his body on the top of the sofa back. “See, LaLa, I kept trying to wake her.” I laid my hands on her chest. I’d never performed CPR in my life, but what do you do when your grandmother lies lifeless? You perform CPR. I interlocked my fingers and pressed my hands on her chest. She hardly moved. I whispered in her ear, “Please wake up, Grandma. Please wake up. We need you.” I pumped again. And again. I grabbed my cousin and told him to go to his room and answer the phone that had been ringing off the hook. Someone knocked on the door and I let them in. It was chaos. My mother arrived, and I watched her perfectly applied makeup run in the living room while the weight of her body lay over her mother’s. She was angry at me. At my grandmother. At everyone. My mom lost her mother that morning, and in some way, I think I lost my mother, too.

Where the fuck do dead dads go? What about dead grandmothers? They were both so young. Where do I find all the people I’ve lost? I’ve spent so much time talking and teaching others how to edit and let go. I’ve spent so much time on lessening the weight of garments lost to make space and time for the joy and creativity in getting dressed. Yet, I have not made peace with all the people I’ve lost in the process. I know they’re in the clothes, but they aren’t clothes. I wish they’d all just come back home.

My jewelry is a mix of old and new, passed down and found. There are earrings from my grandmother and things from women-owned brands that have been sent to me over the years. I love that I can pick up something and know who gave it to me or where I was emotionally or physically when I got it. Even though my closet can get a little disorganized, everything is intentional.

5 Rules

for

Continuing

to Heal

from Loss

1. Grief has no expiration date. It doesn’t magically disappear and there is no set of steps that then cure the loss of someone. You sometimes get better with it. Sometimes, it hits you right in the gut and forces you to lay it all down. Kneel, my friend.

2. Your version of grieving doesn’t look like your partner’s, mother’s, sister’s, or friend’s. It can feel isolating, but remember that the face of such a tremendous feeling is unique to each person it overcomes. Be soft with those you love.

3. It’s OK to talk. And keep talking. If there is someone willing to listen, let them. If you can write, write.

4. When you are forced to remember who you’ve lost, whether it be in the face of a stranger or in a quirky odd thing that only you two shared, steal those moments. They can hurt, but count them as joy.

5. Professional therapy is a great tool to have in your toolbox. If you have the means, please don’t be afraid to use those who are trained to help. There are plenty of free hotlines and community-run programs that focus on grief. Though they aren’t as intimate as a therapy session, they still are powerful and help create community.

Whenever I am purging a client’s wardrobe (or my own), I make them ask three questions when assessing each piece. Then, we decide what to let go of and what to keep. Ask yourself these questions when working with your own closet.

1. When is the last time I wore it?

2. Are there three events or instances that I can wear it over the next two weeks? And if so, where and how?

3. Why am I holding on to it? What story does it hold or what story am I hoping to create in it?

Sade

Lythcott

CEO,

the National

Black Theatre

I met Sade at a dinner party hosted by our friend Sarah Sophie Flicker more than two years ago. We sat next to one another, and I was mesmerized by the way she spoke with passion on just about Every. Single. Topic. Sade’s work streams within a bloodline of legendary Harlem-proud activism celebrating the arts. She’s the kind of real New York woman full of grace, power, and a wealth of knowledge. She talked with her hands and kept me entranced. Through the years, we’ve kept in touch while her world has expanded with a new marriage and a baby and plenty of wonderful and meaningful work in between. Here is our conversation.

LY Your life is so full, but when you think of the word loss, what immediately comes to mind?

SL I equate the word loss to an emptiness—a sense of grief. The unreplenishable. There is a permanence to the word as I have come to know it. I guess I’m not positive that things lost can ever be found. As dark as that may sound, it is the thing that gives me the most peace in dealing with loss. Loss has its place. It is to be acknowledged, honored, not swept under the carpet or run from. It is the honoring of loss, the making sacred, that helps you heal, move on, and rediscover or come into a new relationship with whatever the void is. It is the heart work of this ritual that allows us to be the most free.

LY How has this view of loss impacted your personal life and your work?

SL The sudden loss of my mother (who was also my best friend) was devastating. The shock of her passing rendered me helpless, hopeless, and stuck in both the past and her passing. Life after loss is never the same, and reaching for it to be only retraumatized me. What I had to learn for my life and ultimately my work was that the universe is always conspiring for our highest good, whether we understand it in the moment or not. You must allow yourself to feel the loss as a part of your journey, not as a destination. Let it flow through you in order to steward you to where you were meant to be. My mother’s passing has stewarded me into the fulfillment of my life’s work at the National Black Theatre. It was by honoring my loss (instead of preserving it, which was my first impulse) that I ultimately found my way back to me.

LY Now that you have a son, has this loss transformed?

SL Being a mother has absolutely shifted my relationship to all things . . . in profound and unexpected ways. No one ever really talks about the deepening of relationships with the ones we have lost, but it can absolutely happen. I feel like through the birth of my son I have come to know my mom and her choices in a new and profound way. There is a sweetness to knowing that she is Thelonious’s guardian angel. If I deal with loss at all since becoming a mother, it has more to do with wrestling with the loss of my old self.

LY It often feels like black women are supposed to carry what is lost and what is gained for an entire family or community. Do you feel like this is true, and is there any advice you can give for a woman of color who is currently going through this?

SL There is this amazing young Nigerian poet named Ijeoma Umebinyuo whose work I love. She has this one poem [published in her 2015 book Questions for Ada] that says:

Bless the daughters who sat, carrying the trauma of mothers. Who sat asking for more love, and not getting any, carried themselves to light.

I think this poem speaks volumes to the weight of what we carry as women of color. My advice is simple. Always and in all ways: Travel light. Keep reaching for the light. Be the light. And remember to let kindness, patience, gentleness, and grace light your way as you journey into finding and falling in love with yourself.

LY If there’s one piece of advice you could give to a young WOC, what would it be?

SL Just that you are both Sister and Goddess and so is every single woman of color you encounter. So please treat each other that way. We are way more powerful united than we will ever be divided.

LY How can other women and sisters support one another when it comes to healing and expanding?

SL Let go of everything that isn’t love and keep showing up for one another. Keep holding space for each other’s healing. Don’t be afraid to unearth the darkness of our wounds so that we may bathe them in light. Learn how to build and maintain sacred, safe, and brave space for ourselves first and then our communities. Call on your ancestors for every damn thing, and remember you are forever protected by their prayers. Have and keep the faith. Our sisterhood will heal the world; after all, it is the most righteous act of revolution.

LY I love your dress! What is the story behind it?

SL Every time I travel to different countries in Africa, I love to check out local fashion designers (especially women designers). The dress I’m wearing is from a young designer from Zambia named Kapasa Musonda. You can find her unique designs on Instagram: @mangishidoll.