There are no photos of me from the summer I was born. I was dry and scaled. Brown and bald. Seven pounds and six ounces of unattractive bliss, caused by very little amniotic fluid, the bad luck of a twenty-three-year-old carrying her fourth child in the throes of an abusive marriage. I shed like a snake for weeks. My mother would touch me, and the dry outer shell that consumed my first few months of life would flake off. My mother says my due date was July 1, 1989. Then the fourth. Eventually, they induced on the fifteenth at Downstate Hospital in Brooklyn. All of my brothers and my sister have that dusty, pale hospital photo that plagued the eighties: pink bow. Blue bow. Striped Hospital blanket. Furrowed brow and cone-shaped head. Each of them, except me. While my mother thinks I was beautiful, the lack of photographic evidence mixed with the description of me as a newborn leaves little to help me imagine such. It is no surprise that I grew up questioning how we come to define beauty.

At that point, my dad should have been off drugs. My baby photos show my father with a wide smile, often sporting a drink in his hand. My mother: her large and beautiful forehead, her head of thick jet-black hair, and her eyes always communicating something more than what the lens intended to capture. My earliest memories are of her smiling and smelling faintly of Wind Song or Chanel No. 5. My dad’s smile reached from ear to ear, his deep dark skin smoothing at the corners. Those first few years of my childhood, when we lived on Saint Marks Avenue in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, were full of typical tropes of the eighties: plastic-covered white sofas, merlot turtlenecks, fur-trimmed leather coats. And babies with babies.

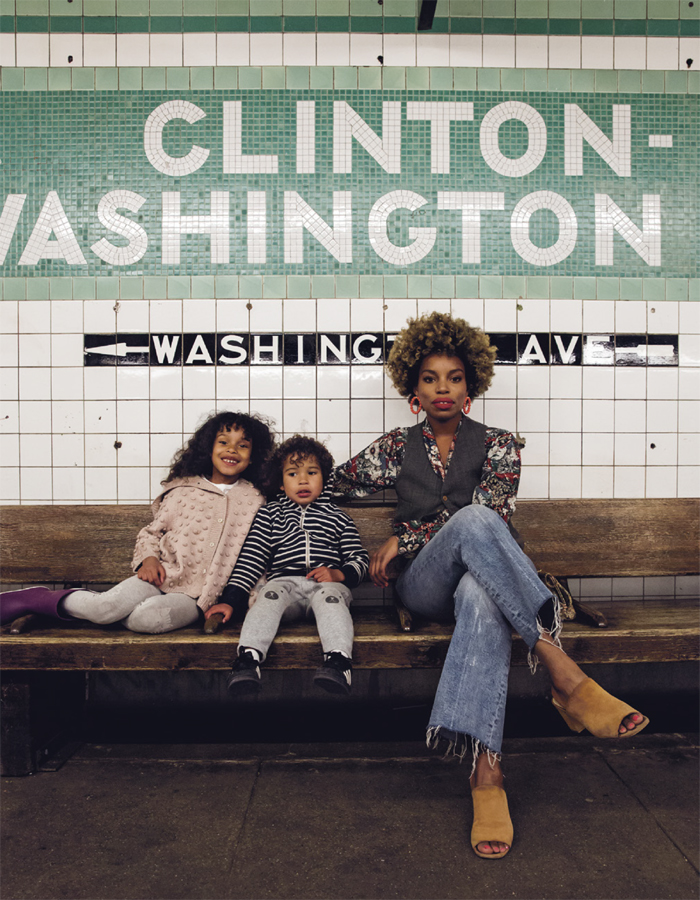

Today, I am not too far off this path. I had my daughter, River, when I was twenty-one, and then spent the next few years trying for my son, Oak. In all, my twenties have been dedicated to raising babies; this, together with my past, has shaped a version of beauty that is in constant evolution. I don’t mean beauty as the physical or visual realm we often align it with; I mean a kind of beauty that exists in relation to, and because of, the ugly. The crack my father smoked. The beer he made me grab from the fridge, using me to sneak alcohol behind my mother’s back that one summer in Silver Spring, Maryland. The same summer I jumped on his back, hitting him with my fists, in defense of my mother. The vitiligo that plagued me and filled my face with white fire at seven. The lupus that I assumed grew within my blood. The physical fights. The bullying. The births. The pain. The loss. The weight gain. The weight loss. The sight of my grandmother cold and still in her apartment when I was eighteen. But, also: beauty in the floral wallpaper she meticulously layered over and over again in her Classon Avenue apartment. The second kitchen she turned into a walk-in closet, filled with metallic suits, taupe and navy espadrilles, and men’s blazers. Beauty in the window boxes full of flowers she sang to and tended each day. The Sundays when my mother sat me down on the hardwood floor, braided my hair, and sang me songs that comforted me throughout it all. The act of resistance in it—in choosing to see beauty through the grit each day. Beauty as resistance. Beauty as survival.

I remember being so excited about that little dress. It was a Christmas gift along with the slippers.

My mom was—still is—big on Christmas, so it is no surprise that she took us to whatever Santa she could find. This one was a Rent-A-Center Santa, and, of course, I wore a two-piece floral sweat suit. Back then my mom bought me a lot of outfits like this, which I would wear together or mix and match. I loved them tremendously.

River and me on an Impossible Polaroid, shot by Peter in Bushwick, Brooklyn. We found that Ergobaby baby carrier at a stoop sale, and I loved the worn-in feeling of it and the way River would look up at me and we would be able to interact and have conversations. It helped balance the baby and me; I was able to wear clogs and heels and still feel like I had a bit of style while carrying her.

After River was born, I attended college for writing and literature and started my blog, LaTonya Yvette (originally Old, New, and the Wee One Too), as a place to document that beauty within style and motherhood. And I was proud that my blog occupied a predominantly white space. At first, I told our story without truly sharing my story. River was tiny and adorable and half white, and we spent many of our afternoons running around the city. Sharing our adventures felt unique, but soon, the blog became an outlet to connect with other women like myself: young, stylish mothers. Before the blog, all the other mothers I knew seemed to have planned their pregnancies. They gave up knit skirts for yoga pants and on-demand breastfeeding—and they had fifteen years on me.

I was playing the blogging game until a very real and public experience called me on my bullshit. I had announced my second pregnancy and begun to document it on the blog by standing under Manhattan street signs that matched the number of weeks along I was. And then I lost the baby. While the weight of this loss was so personally layered, adding a public dimension required that I open up and truly honor the experience of grief. I wrote a short and sweet post explaining the baby my then-husband, Peter, and I lost, then another when it looked like our world had been pieced back together—when in reality, it hadn’t. The supportive emails and comments that poured in stunned me. They cared for me during the day and when I couldn’t sleep at night. They never really stopped. They helped me pull myself back together, but also required that I slowly lift the veil on the many nuances—whether style- or motherhood-related—that in and of themselves compose womanhood. Even with the transparent online shift that occurred after losing my baby, the stories I share in this book barely revealed themselves on my blog.

My second pregnancy, right before I lost the baby. Seventeen weeks, standing under a 17th Street sign in Manhattan. I did this as a way to document the weeks for my blog.

I had so much fun dressing River. In the early days I stuck to yellow and orange, and these were one of her first pairs of real tennis shoes, which she adored. We were on our way to buy a plant, and it was a chilly day, so I layered a basic outfit with an Ace & Jig duster.

Photographed with Oak a few days after he was born. I’m wearing my favorite muumuu and box braids.

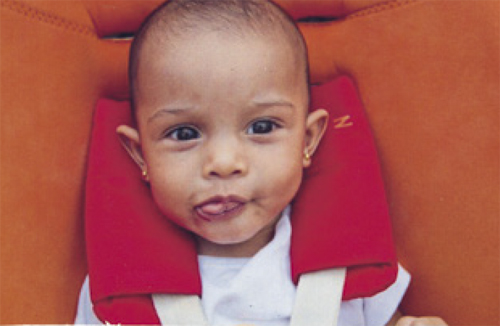

I purchased this Quinny stroller from eBay when River was around four months. It was a pricey mistake, but, of course, I loved her in it. This was snapped on our first day traveling from Bushwick to Williamsburg. That tongue!

Before River was born, I would thrift a few pieces for her during my pregnancy. This continued until she was about four and started to ask to dress herself. This outfit was one of my favorites: a small felt-like dress with buttons paired with shorts and sunglasses that would flip up to reveal clear lenses. She would pull that green wooden alligator all around Brooklyn like it was a pet of hers!

This book is about the growth of a young woman of color through the many phases of her life. But as I was writing, I realized that it is just as much about my family—my brothers, my sister, my mother, my father, my grandmother, my uncles, and my aunts. Back then, everyone had a hand in raising me, and in defining the way I see and tell a story today. These are my stories in a sea of experiences that don’t belong to just me.

Before there was a black girl creating a business and thriving in a world dominated by white women; before I chopped all my hair off in a hole-in-the-wall Dominican hair salon in Bushwick, Brooklyn; before the summer I fell in love with a white boy from Salisbury, Maryland; before I had my children, River and Oak; and, yes, before I lost the baby in between. Before the several moves in a matter of years; before the bullying and self-hatred; before my skin started to peel and give way to white patches—before all of that, I was born the fourth of a rowdy group of five, with barely three years between each of us. My brother Tony was the eldest, then DaMãar, Brittany, me, and Dario. Today, some of us live in Brooklyn, and some of us remain in Virginia, the last state where we were all living together. And—this is no exaggeration—there is not a day that goes by when I don’t miss living with them. It’s an odd feeling; not necessarily missing your childhood, but missing those who were part of it. It is in part due to my mother forcing all of us to care for one another, but using that care as a ground of existence. “You’re all you have,” she’d say, whether we were living in a fancy house or moving from one home to the next because we were being evicted. And at the same time, my mother relied so much on her own mother and on her siblings to help raise us when things got tough. My uncle bought us many of our expensive sneakers, and my aunt gave me my first Tommy Hilfiger belly shirt, which I wore at the West Indian Day Parade when I was no more than twelve.

Since I started my blog six years ago, every one of my collaborations has been woven out of, or been connected to, a story from my past. It is something I cannot escape. Something I do not want to escape. When I was a kid, words were a way for me to escape; for many years, I watched my mom write, and I would read her pages at the glass dining table or on the couch on a Sunday afternoon.

From the summer of 2009. I’m wearing a vintage shirt of my grandmother’s and a fedora that I purchased at Peachfrog, a shop I worked at that year.

My grandmother, photographed on one of her “dress-down” days. She’s wearing a vintage skirt, blazer, and glittery gold slides. Her hair isn’t too curled here, which means she was likely wearing a vintage hat and had taken it off.

Me and my brother Dario in front of my mother’s house in Maryland. This was the house she owned. It was also the time my vitiligo felt its worst.

Me and Dario at a fair that was hosted by my dad’s job for the Metro Subway in Maryland. I picked out that green shirt and green skirt. I wore the outfit for years. I did that with many pieces of clothing because I gained very little weight as a child and could keep wearing the same ones.

When I became an adult, style was a way for me to create. I was seventeen and working at Skechers in Time Square, where, somehow between the swarms of tourists and overwhelming lights, I played around with the way the sneakers were lined up on a shelf or staggered them to make purchasing most optimal. Then there was my job at Esprit, where I often felt perplexed and frustrated by the visual team’s lack of creativity. Why did the windows need to be created based on graphs and sales charts rather than on what drew people in with pure creativity? From there, I started assisting a soft-spoken German stylist named Sabina. I believe I always had it in me, but there was something about Sabina’s honest and gentle encouragement, which was often tied into the realities of being a woman, a New Yorker, and, eventually, a mother, that felt like the necessary push to play around with style as a career. Later, while both of our careers kind of ebbed and flowed, Sabina was River’s first babysitter and reassured me that I had all that River needed.

So much of my life can be seen through foggy, colorful, layered, and yet detailed snapshots around beauty and style; the stories in this book unblur the lens for me, and I hope for you, too. I have learned that clarity often happens in the moments when we share. Each chapter includes practical advice and lifestyle takeaways, serious and honest moments, and, of course, moments that are completely light and hilarious. And in this book, the sharing goes beyond just me, as I share not only my experiences, but those of other women of color. At the end of each chapter, I interview a woman, like designer Aurora James of Brother Vellies or doula Latham Thomas of Mama Glow, who in some way aligns with my essay. If I have learned anything from growing up, it is that no experience is only my own. Yes, the circumstances are unique to me, but often, there is a thin sliver of thread that ties all of us women and our experiences together. I hope this book serves as a guide for you, wherever you may be.

All in all, this is a love letter to women—mothers, daughters, hair stylists, photographers, artists, writers, sisters, friends, and, of course, black sisters. Sisters, who are all too often made to feel as if beauty—whether it be gritty, natural, or traditionally beautiful—is made only for the consumption and advancement of others. Here’s to us and sharing all the stories that live within us and that are for us. I love you.