Over the decades I have been asked to deliver lectures, disquisitions and addresses on numerous subjects and for the most part I manage to excuse myself. Just occasionally, however, a subject is so appealing or a cause so close to my heart and my diary so surprisingly and unwontedly amenable that I find myself under an obligation to disgorge as requested. I offer you the opening of a lecture I gave in the Royal Geographical Society’s lecture theatre some years ago: the first Spectator Lecture, or Speccie Leccie, as I called it. I have scavenged from it and present the exordium so as to make coherent some of my thoughts about America, a country I was becoming more and more fond of and anxious to visit more and more often.

Thank you. Thank you very much. Good lord. Well, well. Here we are. Gathered together in the very lecture theatre where Henry Morton Stanley once told an enraptured world of his momentous meeting with Dr Livingstone. Charles Darwin was a member and gave talks in this same hall. Sir Richard Burton lectured here, and John Hanning Speke … spoke. Shackleton and Hillary displayed their intimate frostbite scars to a spellbound RGS audience. Explorers, adventurers and navigators have been coming here for the best part of 180 years to tell of their discoveries. If only at school, geography teachers, surely the most scoffed and pilloried class of pedagogue there is, if only they had concentrated less on rift valleys, trig points and the major exports of Indonesia and more on the fact that geography could promise a classy royal society with the sexiest lecture theatre in the land. Actually, now that I think of it, one reason for me to be fond of the subject was the circumstance that in my prep-school geography room there were piles and piles of shiny yellow National Geographic magazines available for skimming through. These, with their glossy advertisements for Chesterfield cigarettes, Cadillac sedans and Dimple whisky, gave me my first view outside television of what America might be like. But there was another reason religiously to scan the magazines …

National Geographic, before it became best known for an imbecilic and embarrassing suite of digital TV channels, was – thanks to its anthropological coverage in a pre-internet, pre-Channel 4, pre-top shelf age – the only place where a curious boy could look at full colour pictures of naked people. For that alone it deserves the thanks of generations. One did get the false impression that many peoples of the world had protuberances shaped exactly like a gourd, but never mind.

National Geographic made films too, and at my school these would be run through an old Bell & Howell projector by the geography masters to keep us quiet and to give them time to beetle off and pursue their amorous liaisons with matron or the whisky bottle, depending on which teacher it was. ‘Fry, you’re in charge,’ they would never say on their way out. But what strange films they left us to watch. I seem to recall that the subjects were usually logging in Oregon, the life cycle of the beaver or the excitements to be found in the National Parks of Montana and Wyoming. Very blue skies, lots of spruce, larch and pine, and plenty of plaid shirtings. The unreliable speed of that hot and dusty old Bell & Howell rendered the soundtrack and its music flat then sharp then flat again in rolling waves of discord, but it was the commentators that gave me raptures with their magisterially rich and rolling American rhetoric. What a peculiar way with language they had, employing poetical tricks that had been out of date a hundred years earlier. My favourite was the ‘be-’ game. If a word usually began with the prefix ‘be-’ it was taken off. Thus ‘beneath’ became ‘neath’ and so on. But the ‘be’ of ‘beneath’ wasn’t simply thrown away. No, no. It was recycled by adding it to words it had no business being anywhere near. Which would result in preposterous declamatory orotundities of this nature: ‘Neath the bedappled verdure of the mighty sequoia sinks the bewestering sun,’ and so forth. And what is the proper name for this rhetorical trope, also much deployed? It would start with the usual ‘be-’ nonsense: ‘Neath becoppered skies bewends …’ but then this: ‘the silver ribbon of time that is the Colorado River’. The weird and senseless maze of metonym and metaphor that was National Geographic Speak in all its besplendour was a great influence on me, for where others had rock and roll music, I had language …

Self, Ben Elton, Robbie Coltrane, Griff Rhys Jones, Mel Smith, Rowan Atkinson.

An idiot and an imbecile.

Ready to lay down their lives for my country.

A blithering idiot and a gibbering imbecile.

Radio Times 1988 Christmas Edition: Saturday-Night Fry feature.

Hugh, Jo and I.

With sister, Jo.

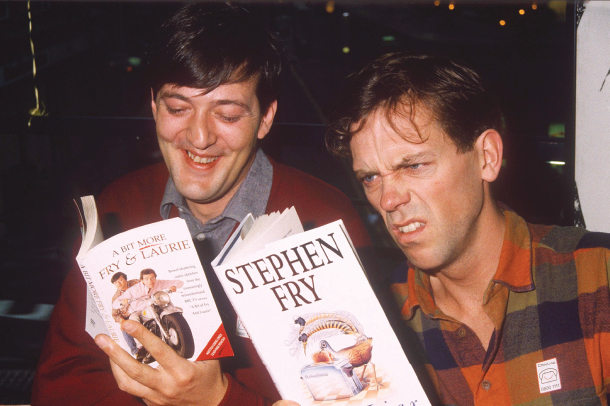

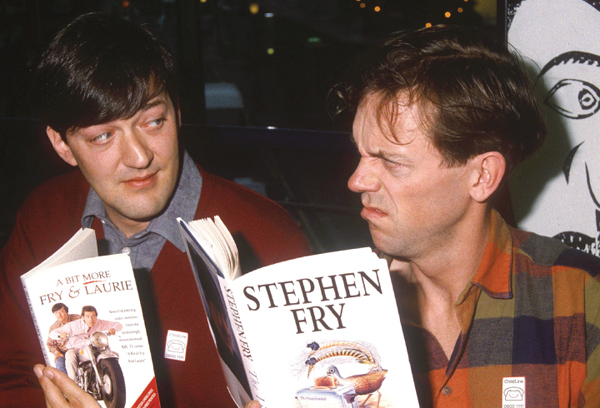

A signing at a Dillons bookshop. London, 1991.

Hugh’s warmest, most approving look, 1991.

A profile of a liar for the publication of The Liar, 1991, with sister Jo.

Tourrettes-sur-Loup – my best audience.

Tourrettes-sur-Loup – picking on someone my own size.

And so I bewended and bewittered like the large slab of humanity that was Stephen Fry. Despite my passion for all things American and my obsession with its language, literature, history and culture, I didn’t visit the country until I was well into my twenties. I had adapted and rewritten the book of the British musical Me and My Girl as alluded to passim, and it was decided that a Broadway production might be worth attempting. With Mike Ockrent, the director, and Robert Lindsay, the star, I took a PanAm flight from London to JFK. I had never been so excited in my life. My first view of the Manhattan skyline was like Dante’s first view of Beatrice, Cortez’s of the Pacific and, I dare say, Simon Cowell’s of Susan Boyle. I fell for New York quite as much as Wodehouse, W. H. Auden, Oscar Wilde and my other literary heroes had before me. But we were only there for rehearsals. The musical was to try out and open in Los Angeles, California. My first visit, and I was to live for a while in both Manhattan and Beverly Hills. My cup ran over like a blocked gutter.

In Broadway’s theatre district there is a famous eatery called the Carnegie Deli. It features in Woody Allen’s Broadway Danny Rose, you may remember. It was on my first full day in America that I went in there and ordered a pastrami sandwich. Big deal, you may say. Oh yes. Big deal. Huge deal. For those who have not had the pleasure, a proper New York deli pastrami sandwich is about the size and thickness of a rugby ball. Two thin layers of rye bread and in between slice after slice after slice of warm, fatty, delicious pastrami. On the side is served a pickle or so. Hold that image. Me facing off with a vast pastrami sandwich. Right. We now scuttle to LA. I blew all my per diems on a single weekend in the Bel Air Hotel, luxury on a scale I had never even imagined, let alone contemplated. Robert Redford winked at me from across the breakfast room. I nearly trod on a dog belonging to Shirley MacLaine. My over-running cup ran over even more till it was more like the Trevi Fountain than any sort of cup I know.

Then back to New York. I am happy to say the opening night of Me and My Girl was everything one could have hoped for. The New York Times raved; we were a hit. I won a Drama Desk award and a Tony nomination; Robert Lindsay went on to win a Tony and a hatful of other trophies for his brilliant performance. There and then I promised myself that one day I would live in New York, this city from whose sidewalks you drew electricity like a tube train from its tracks. At the time I had been staying in an apartment belonging to my friend Douglas Adams. On the flight back I garrulously chattered away to an American lady sitting next to me about how I loved America and was planning to live in New York.

‘But honey,’ she said – she was rather in the Rosalind Russell Auntie Mame mould – ‘honey, you told me you’d only ever been to New York City and Los Angeles.’

I confessed that this was true.

‘Then you have never even seen America,’ she said.

I suppose regarding a part of something as being congruent to its whole might be viewed as a kind of pars pro toto fallacy or lazy synecdoche, but I didn’t truly understand what this woman meant until, as the National Geographic might say, I bethought me of the colossal continent of succulence that was a Carnegie Deli sandwich. How could anyone say they had eaten a Carnegie Deli pastrami sandwich if in fact they had only gnawed at the thin slices of rye at either end while the whole continent of meat lay untouched? How could anyone say they had experienced America who had only nibbled at New York and Los Angeles?

One of the tasks I was – er – tasked to do when in Los Angeles some time in 1990 or 1991 was to pick up a script in Las Vegas and transport it to London. To fax an entire 120-page script from Las Vegas to London might have been within the budget of a major studio, but not within the budget of Renaissance Films, Ken Branagh’s production company, founded with a City gentleman turned producer called Stephen Evans. Email attachments were but a glint in the eye of the future. If you had a document to send you used a courier. Couriers came in the shape of DHL and FedEx or possibly in the shape of Stephen Fry.

I cannot remember what had taken me to Los Angeles in 1991, or even if I have the year right, but I do know that the previous winter I had invited Emma Thompson and her new husband, Ken Branagh, for a week at my Norfolk house. They had seen me chopping wood. We had talked of this and that and somehow, as is the way with Ken, a story idea had been born or confirmed in his head.

I think perhaps on reflection that I may have got this wrong. Maybe it was Martin Bergman* and his wife, the American comedian Rita Rudner,† who had been up to Norfolk, for it was certainly they who wrote the screenplay in question. Oh memory, what a ditzy queen you are.

Well, well. The facts of the matter are that Ken knew I was in Los Angeles and asked me to stop off in Las Vegas and pick up the latest version of the script. I had not read any version of it, but had agreed to be in it, such was my instinctive trust of Ken and such were his extraordinary powers of persuasion.

The film was to be called Peter’s Friends, and I read it on the plane back from Los Angeles with a mounting sense of horror. It was funny, I thought, but it was about us. About Hugh and me and Emma and Tony Slattery and our Footlights generation seven or eight years on. Ken had enjoyed great success with the film version of his triumphant Stratford Henry V and now he wanted to make a kind of British Big Chill.

Hugh and I, perhaps because of the permanent guilt derived from our perceived privileged upbringings, instinctively recited in our minds the likely response of critics whenever a new project arose. We had in mind some kind of antagonistic Time Out reviewer. The wrinkle in his nose, the snort of his derision, the slow downward curl of his lips – we were there before him, writing his copy as if inside his head and the heads of everyone else. This we will return to in a moment.

In the spring of ’88 I played the part of the philosopher Humphry in Simon Gray’s The Common Pursuit in Watford and at the Phoenix Theatre in the West End. During that time I had been making the television version of Delve Special, which had been retitled This Is David Lander. Filming all day and then just making it in time to the theatre and after that being naughty in the Limelight nightclub with rock stars, snooker players and other disparate lowlife legends seemed to be something I could manage, although my doctor popped into the dressing room at the Phoenix twice a week to inject me with B12 to keep my energy levels up. I don’t remember asking for this, so I assume it was the show’s producer who probably worried, as producers do, that I might be running out of fuel. The run of the play was followed by a period Hugh and I had set aside to write all the material for a comedy sketch show that we decided after much agonized debate to call A Bit of Fry and Laurie.

In the early spring of 1989 we began taping the first full series of this (‘a lacklustre throwback trapped in an irrelevant Oxbridge past’, we imagined Time Out snarling furiously). In the summer of that year we recorded Blackadder Goes Forth (‘a sad dip in form after the delights of Blackadder the Third’, Time Out would be sure to mutter) and immediately after that Hugh and I filmed the first series of Jeeves and Wooster, again sharing throughout the shoot what we imagined would be Time Out’s verdict: ‘while the rest of the world leaps ahead in innovation and edge, Fry and Laurie welter feebly in a snobbish and puerile past’.* This had come about when a fellow called Brian Eastman had asked for a meeting. Eastman had previously worked in music for the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the British Council and now had a company that produced most notably the series Poirot on ITV. It was his plan to bring Wodehouse’s Bertie and Jeeves to the screen, and he felt that Hugh and I were good casting. Strangely, to us at least, he was quite open as to which roles we felt each should play. It seemed obvious to us that Hugh was a natural Bertie and I more suited to Jeeves. Hugh put it this way: Bertie’s voice is a trumpet, Jeeves’s a cello.

Actually, such was our insecurity and fear of failure we didn’t really believe it could be done and might easily have turned Brian down, had it not been for a fear of any other two actors playing the parts. The pessimism in this case wasn’t entirely our usual flabby lack of confidence, so much as an immense respect of, and devotion to, Wodehouse’s work. His novels and stories, like any writer’s, are composed of plot, character and language. What makes Wodehouse stand head and shoulders above any comic writer of the twentieth century (indeed almost any writer, regardless of genre) is his language. In the end we decided if we could get across character and plot and only a small amount of that peerless prose then we might turn enough people to reading the books, consigning them to a lifetime of endless pleasure. Clive Exton, who wrote the adaptation, was best known for his chilling screenplay 10 Rillington Place, the grim, murky retelling of the Christie murders. But he had since moved to another world of Christie murders altogether as one of the lead writers on the Poirot series.

Fry and Laurie seemed sometimes to be a desperate affair, writing and staring at the wall and not believing we were at all funny, performing dozens of sketches before a live audience on each recording evening and then worrying straight away about the next week. But I was working with Hugh, my best friend in the whole world, and while sketch delivery, like any kind of birth, involves pain and squealing, it was a period of fecundity, laughter, freedom and friendship that I would have been lucky to have experienced had I lived a hundred lives. Sometimes I will be sent a YouTube link on Twitter and out of curiosity follow it up only to discover that it is an old Fry and Laurie sketch that I have almost entirely forgotten. Forgive me if occasionally I find myself laughing and actually feeling proud. Naturally, as we all do, I wince and writhe in embarrassment at this mannerism or that, but I do really believe that some of our writing and performing was … well … top hole …

Straight after Fry and Laurie we made Blackadder Goes Forth. The audience that came into the BBC studios, as I have mentioned, had almost certainly seen Blackadder II and Blackadder the Third on their televisions at home and were somewhat alienated by new characters and settings. In rehearsal there was a lot of pacing, smoking, coffee-drinking and throwing out ideas, not to mention having ideas thrown out. We were young, we were buzzy and we were also, although we had no idea of it at all, making a comedy series that for whatever reason appears to have stood the test of time. The character drawing and imagination of writers Richard Curtis and Ben Elton, our own additions, I would modestly suggest, the extraordinary talent of Rowan, Hugh, (Sir) Tony Robinson, Tim McInnerny and the late and hugely lamented Rik Mayall all seemed to combine in a way that simply clicked. John Lloyd, the producer, kept us all on point, as Americans like to say, but on a couple of occasions we made such drastic changes to the storyline that whole new sets had to be ordered from the production designer just two days before recording, and it was John who manfully took the blame each time. My own proudest achievement is perhaps not the playing of the insane General Melchett, but the suggestion after the first read-through that Tim McInnerny’s character’s name be changed from the proffered ‘Perkins’ or ‘Cartwright’ to something that might explain his animosity, suspicion and hostility to all around him. I wondered if ‘Darling’ might not work, and Rowan and Tim ran with the ball as only actors of their quality could.

Jeeves and Wooster, which started more or less straight after Blackadder finished, was unalloyed pleasure. Hugh and I both took to single-camera filming (as opposed to the multi-camera TV studio set-up then customary in which sitcoms were recorded on tape) like ducks to bread crusts. We had wonderful fellow actors to work with and lively, funny crews full of banter and inventiveness. Between them they had been involved in many of the best films ever to have come out of Britain, from Dr No to Dr Strangelove.

Somehow during this period as well as my involvement in those three television series I had also written four or five twenty-minute films for John Cleese’s company Video Arts. Video Arts specialized in training films for business and industry. These films had been constructed around psychological ideas all vetted by John Cleese’s pet psychologist, Robin Skynner, with whom he’d written the book Families and How to Survive Them. They had thrilling titles like How to Schedule a Meeting, How to Run an Interview, How to Succeed in a Job Application. I secretly called the whole project ‘How to Make Money by Stating the So Fucking Obvious It Makes Your Nose Bleed’. If businesses needed to be told in firm language:

• make a list

• stick to it

then no wonder the British economy was swirling round the lavatory pan. They were fun films to make, however, and to be around John Cleese, a towering hero from my early teens, still made me rub my eyes with disbelief. I had written roles for myself, John, Hugh and Dawn French. Other parts were played by Ronnie Corbett and Julian Holloway.

It was during this period, post Fry and Laurie, Black-adder and Jeeves and Wooster, that I made simply the best decision in my entire life. It saved my health, my career and (for a time at least) my sanity.

While I had been deep in this absolutely brutal schedule (although it seemed natural to me), my sister Jo had completed a TV and film make-up course in London, and one evening we had dinner in Orso, the popular Covent Garden restaurant.

I had been turning something over in my mind and finally, over the panna cotta alla fragole, I ventilated it.

‘Jo, I know there’s always the possibility of your going off to do make-up work on a film or something. And I know Richard might get stationed abroad,* but do you think you might like …?’

‘Yes?’

‘Well, if this is out of order just spray wine at me, but how would you feel about …?’

‘Go on.’

‘Well, over the last few years I’ve started to get more and more fan mail, more and more requests for appearances and after-dinner speaking and the lord knows what else. It’s kind of out of control …’

‘Right …’

‘My diary is so packed that I can hardly keep up with what I’m doing, and I need, well I need a …’

‘A secretary?’

‘Well, the term for it is Personal Assistant. PA. But in your case, being a personal sister, you’d be a Personal Assister.’

‘Oh God, that is so exactly what I hoped you’d ask me. I was going to suggest the same thing. I’d love it. I’d love it more than anything.’

For the past twenty-six years, then, Jo has been my PA. She is the best PA anyone ever had. Naturally I would say that out of family loyalty, but a story illustrates the point.

During filming with John Cleese somewhere in West London for a Video Arts project, Jo visited the set with her Filofax to go over the next week’s diary business. This was before you could electronically sync diaries over the air, well before PDAs and smartphones. She stayed for lunch, joined John in watching me film a scene with Ronnie Corbett and then biffed off.

About ten minutes later John stalked over.

‘Well, don’t I feel a total dick.’

‘What’s happened?’

‘All my working life I’ve looked for the perfect assistant, and you, you bastard, have found her. So naturally I said to her while you were on camera, “Whatever he’s paying you, I’ll double it.”’

‘Ah. What did she say?’

‘She smiled very sweetly and said, “That’s very kind, Mr Cleese, but he is actually my brother.” I don’t know when I last felt such a complete tit.’

‘Well, you weren’t to know …’

I was, of course, very pleased to hear such praise. It was entirely typical that Jo herself never mentioned this story to me. I finally raised it a week or so later.

‘You do know John told me about trying to poach you?’

‘Oh that! That was funny …’

‘You could have told me, and I’d’ve had to double your pay …’

Which I think, I hope, I did.

It is no exaggeration to say that I would not be alive now were it not for Jo’s gentle but firm control of my life. I tease her by calling her Martina Bormann, my diary Nazi, but it would have been impossible to have done a tenth of the things I have done without her understanding of how diaries, film schedules, call sheets, production companies, television executives, airports, drivers and above all her capricious, weird and impossible boss/brother operate. Or fail to.

I was called one week the following year, which was probably 1990 but don’t quote me, to visit a certain Roger Peters, who was installed in splendour in Suite 512 of the Savoy Hotel. The man turned out to be an American of middle years. He gave me to understand that he was the heir and last lover of the American composer Samuel Barber. I had always believed that Barber had died of a broken heart after his long-time partner and fellow musician Gian Carlo Menotti traded him in for a younger model, but it seems he found Roger Peters at the end.

Roger, it seemed, had the film rights to Noël Coward’s Hayfever and wondered if I was interested in writing the adaptation. I politely demurred, knowing that: a) Hayfever was Coward’s favourite play and he had specifically given orders that ‘no cunt ever be allowed to fuck about with it’; and b) it was all set in one place and just about one time, adhering as closely as possible to the Aristotelian unities, making it a bugger to adapt for the screen. Not that Reginald Rose and Sidney Lumet didn’t do a bang-up job with 12 Angry Men …

He didn’t seem too offended, and we drank and chatted and gossiped. I guessed that he had asked just about everyone who had ever held a pen or tapped at a keyboard to take on this job, starting, as one did, with Stoppard, Bennett and Pinter and then reaching after exhausting weeks of refusals the bottom of the barrel. Not false modesty, just realism.

The suite was magnificent, with spectacular views that gave out on to the Thames. The idea of living permanently in such splendour filled me with a perfectly unforgivable mixture of envy and ambition. One day, I thought to myself, one day …

The calendar pages peeled and blew away, as Vivian Stanshall phrased it, and it is now early 1992, and I find myself window-shopping along Piccadilly.

‘Hello, Stephen!’

I have a mild case of prosopagnosia, absolutely maddening. Nothing like the severe face-blindness that afflicts some. I have a friend who cannot distinguish his own family members until they say their name. My level of this disorder may not be severe, but it does mean I frequently appear rude. So if you know me and I cut you in the street, it doesn’t mean that I don’t like you and wish to blank you out of my life, it just means I haven’t the faintest idea who you are. Tell me your name, and I’ll be absolutely fine. Most people are the other way about and remember faces but not names.

This fellow, fortunately, was happy to supply the name without prompting.

‘Roger Peters!’

‘Of course,’ I said. ‘How’s tricks?’

‘Well, you know,’ he said, falling into step. ‘You’re just the fellow. Do you know of anyone, anyone …’

Oh God, he’s going to harp on about the bloody Hayfever script again, I moaned inwardly.

‘… anyone who’d be willing to live in my Savoy suite for four or five weeks. I have to go to America for family business and I don’t want to move all my stuff out. I have a deal with the hotel whereby I pay by the year anyway, so it’s just a question of someone suite-sitting. Anybody come to mind?’

‘We-e-ll …’ I said doubtfully, ‘there is one person it might suit. He’s about this high …’ I raised my hand to the level of my head. ‘About this wide …’ I parted my hands to the width of my body. ‘He has a bent nose and he’s talking to you right this minute.’

‘Oh, that’s fantastic! I’m leaving Wednesday. Why don’t you come round tomorrow afternoon, and I’ll introduce you to the floor butler and show you where everything is.’

And so it came to pass that the Savoy Hotel became my home for just over a month. For eleven days of that time we filmed Peter’s Friends. The script that I couriered over to London the year before had been polished and burnished and buffed to a light sheen, but Hugh and I were still, to our eternal discredit, deeply embarrassed about the whole thing. Occasionally in the hallways, corridors and drawing rooms of Wrotham Park (the grand house outside Barnet where we had already shot some scenes in Jeeves and Wooster and where I was many years later to shoot scenes in Robert Altman’s Gosford Park), occasionally, Ken would see Hugh and me looking hangdog and licked to a splinter between set-ups.

‘Everything all right, darlings?’

‘They’re going to hate us,’ I moaned.

‘Who? What do you mean?’

‘“This incestuous, up-itself tale of Oxbridge wankers who reveal their feeble, wimpy and effete so-called ‘problems’ over a weekend of excess in a country house …” Can you imagine how Time Out are going to react?’ (I’ve no idea why Time Out was still the symbol and focus of all our insecurities.)

‘Time Out? Who gives a fuck? It’s read by about twelve people. Seriously, loves, why would you worry about what they think?’

We admired Ken Branagh, and still do, for many reasons, but his magnificent ability not to be downcast or diverted by concerning himself with how some reviewer was going to react to his work was near the top of the list of his accomplishments. Daring and courage are half the battle with acting, directing and film-making. If you have a newspaper reviewer or even the ghost of a generalized and antagonistic public over your shoulder tutting and hissing in through their teeth as you try to concentrate then you are doomed to failure.

Ken, of course, does not associate his place in the world with guilt. He grew up in Northern Ireland in no position of prosperity. His love of theatre was in-born and absolute; any money he managed to earn he would spend on the ferry to the mainland and the bus to Stratford-upon-Avon, where he would watch every season from his early teenage years onwards. It is no accident that he arrived for the first full day of shooting for Peter’s Friends already filled with knowledge, courage and self-belief. It is also, I would argue, no accident that Hugh and I arrived almost sick with apprehension, shame and foreboding. The very good fortune that took us from our public schools (by way of other schools and prison in my case) via Cambridge, the Footlights and into Blackadder, Jeeves and Wooster and our own sketch show, far from filling us with confidence, made us feel utterly unworthy. Please do not think we are asking for sympathy and certainly not for admiration. I speak as it was in our befuddled minds, and you may take it as you will. Perhaps if you have imagination you can see yourself feeling the same way under the same circumstances. Perhaps we were just peculiarly weird.

That a whole feature film could be shot in eleven days was testament to the work ethic of Ken and his crew, the tight unity of time and place within Martin and Rita’s script and, of course, the sparsity of the budget.

Meanwhile, the pleasure of having a car coming to pick me up from the Savoy and dropping me there in the evening was almost more thrilling than anything I had ever experienced. The top-hatted ‘linkmen’, often incorrectly referred to as doormen, were unfailingly polite to me, and I soon got to know the rest of the staff. If you want to know anything about the depths of degradation of the human being, make the acquaintance of the executive housekeeper of any large hotel. You will never be the same again. Discretion prohibits me from going any further, this is a journey you must undertake yourself. It is a bit like telling someone to look up the word ‘munting’ in urbandictionary.com. I take no further responsibility.

Otherwise the joys of suite-sitting were altogether delicious. No bathrobes were ever softer and fluffier, no shower-rose wider and more generous in its precipitation. One small and entirely preposterous annoyance however, a something that got under my skin, was the daily sameness of it all. That ashtray on that table in the drawing room was always placed exactly there. That chair always angled exactly that way. One day I mentioned this to the floor butler.

‘Whenever I come back from filming or from a walk,’ I said, ‘the suite has been wonderfully cleaned and tidied, but – and I really don’t mean this as a criticism – everything is always in exactly the same place. The ornaments on the mantelpiece, the …’

‘Sir, say no more. From tomorrow we will surprise you in small ways each day.’

Which they did. It made me, and I like to think the chambermaid and other staff members, giggle, each time they made a small alteration. Playing Hunt the Ashtray kept me on my toes and freshened the experience of hotel living.

One spare evening I had gone to see a production of Tartuffe in which my good friend Johnny Sessions played a role. Also in the production was Dulcie Gray, whose husband, Michael Denison, had played Algernon in Anthony Asquith’s The Importance of Being Earnest, delivering the line: ‘I hope, Cecily, I shall not offend you if I state quite frankly and openly that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection?’, that very joyous progression of words that had so made me wriggle and writhe and squirm with delight when a young boy.

Michael and Dulcie, a grand and much-loved theatrical couple, made a tradition of having a summer party at Shardeloes, a marvellous eighteenth-century house in Old Amersham with noble Robert Adam interiors and a 1796 landscaped garden by Humphry Repton. The house had been saved, restored and divided up in the 1970s after falling into the customary nursing-home use and further slow decline. Dulcie and Michael had the best ground-floor rooms, giving out over the great lawn; their party, when I arrived, was already crammed with figures from the British film and theatre world. I found myself falling into conversation with Doreen, widow of the great Jack Hawkins, one of my favourite British film stars. Then who should I see across the room? Did my eyes believe it? My favourite of them all, John Mills. A certain amount of excited hopping on one leg, a little light coughing and I found myself sitting on a sofa next to him. He twinkled, just as I expected him to, this nimble, unutterably charming and deeply gifted man. His wife, Mary Hayley Bell, author of Whistle Down the Wind, barked and laughed just as I expected her to.

John Mills was the man Noël Coward wrote ‘Mad Dogs and Englishmen’ for. In the mid-1930s he had been a singer, hoofer and all-round entertainer for a company with the unfortunate name of ‘The Quaints’. Coward, on a journey back from Australia, stopped off in Singapore and saw a poster offering the unlikely double bill (surely not in one night?) of Hamlet and Mr Cinders. It was in the latter that the lithe, lissom and perky Mills impressed. Coward went round afterwards and told him to visit him in London, where he would find a part for him.

Johnny Mills had a genius for friendship. Coward (whom Mills was the first to dub ‘the Master’), Laurence Olivier, Rex Harrison, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes and many others benefited from his selfless and sweetly unegotistical charm.

As we sat on the sofa at Shardeloes I must have bombarded him with dozens of questions about his films and career. The October Man, In Which We Serve, Ryan’s Daughter, Hobson’s Choice, Tiger Bay, Swiss Family Robinson and above all Ice Cold in Alex, Great Expectations and Tunes of Glory had affected me profoundly.

When I paused to draw breath, Johnny asked me what I was up to. I explained that I was in the middle of making a picture with Kenneth Branagh.

‘Oh, no, really?’ said Johnny. ‘I wonder, would you do me a favour?’

‘Anything.’

‘Could you tell Kenneth that, as a friend of Larry Olivier’s, I just know how much Larry would have loved Kenneth’s Henry V and how much he would have loathed the vile comparisons the critics have made. Can you tell him that?’ Johnny was referring to the fact that, while Ken’s Henry V had been an undoubted success, many snarky responses along the lines of ‘Who does he think he is? He’s no Laurence Olivier’ had greeted its release.

‘I’m afraid I can’t pass that message on,’ I told Johnny.

‘Oh.’ He looked rather nonplussed.

‘I’d much prefer you to pass it on yourself. If I gave a dinner party, would you and Lady Mills come along?’

He beamed assent, telephone numbers were swapped, and the thing was fixed.

There is nothing quite like hosting a dinner party in a five-star hotel suite. Yes, of course, I’m aware of how utterly appalling that sounds, but I might as well get the story out.

Here’s how it goes. You tell Alfonso and Ernesto on your floor that you plan to have six guests for dinner next Friday, and they bow with pleasure.

When the day dawns, Ernesto comes in with a menu card and the suggestions from the executive chef and his team toiling in the hypocausts six floors below. You select what you hope is an agreeable dinner* and then, at round about six o’clock, Alfonso, who doesn’t want you under his feet while he sees to the flowers and place settings, comes in and commands that you go on a walk. When you arrive back at the suite everything is simply perfect. The armchairs have been moved back to the window, in a semi-circle looking out over the Thames at dusk. In the centre of the room the main table has had an extra leaf inserted to accommodate seven people: I have invited Hugh and Jo Laurie, Emma Thompson and Ken and of course Sir John and Lady Mills.

Starched white napery, crystal glassware and silver cutlery gleam in the candlelight. Two low bowls of perfect peonies on the table, vases of roses and exquisite flowers I cannot identify distributed about the room. On occasional tables occasional nuts, olives and cornichons. Fortunately this is the age before the uneatable Bombay Mix or palate-destroying pretzel assortment. A bottle of champagne in a silver bucket shifts slightly in the ice. I pour a solacing vodka and tonic, light a cigarette and pretend to myself that I am not a little nervous. When out on my walk I withdrew enough cash to tip Ernesto, Alfonso, Gilberto, Alonso and Pierre as lavishly as might be appropriate.

I have arranged with Alonso that as soon as the first guest has arrived he will come in to serve cocktails and the fizz. If he has not been alerted by reception I will press the bell by the fireplace.

A thought strikes me: perhaps the front desk won’t know who John Mills is! It would be dreadful if so august a figure should slip anonymously in without being treated with the respect he deserves. I call down.

‘Good evening, Mr Fry.’

This was a time when I still got a little disconcerted by the hotel staff being able instantly to identify me as soon as I called.

‘Hello, yes it’s me. Stephen here in 512. I just wanted to say that I’m having a dinner party, and the thing is, the guests of honour are Sir John and Lady Mills, and I hope you will –’

‘… Oh, sir, we know Sir John very well indeed. Rest assured we shall welcome him most enthusiastically. Most enthusiastically!’

Hugh, Jo, Ken and Emma arrived together. We were still young enough to be excited by such a preposterously grown-up business as holding a dinner party in a place like the Savoy.

Alonso made cocktails and stood discreetly by the drinks trolley as we giggled and shrieked.

The buzzer sounded, and we all straightened up and put on serious but welcoming faces.

I opened the door, and there stood Sir John and Mary. He stepped in and looked blinking about him.

‘Oh … oh! It’s …’

I noticed with alarm that he had started to weep.

‘Sir John, is everything all right?’

He took my arm and squeezed it tight. ‘This is Noël’s suite!’

He let go and walked about. ‘Every first night, this was the suite Noël took. Oh gracious!’

It was a perfect evening. Johnny and Ken quickly made friends. Anecdotes rained down, and many beans were spilled. The front desk had already made a great fuss of Johnny and Mary, lining up to greet him at the famous porte-cochère as soon as his splendid old Rolls-Royce had arrived with his faithful driver, factotum and friend John Novelli at the wheel.

It was the beginning of a long friendship between John, the Mills family and me. Not long enough as far as Johnny was concerned of course; he died in 2005 at the age of ninety-three, and Lady Mary, who had lost herself to dementia many years earlier, joined him in death later that year.

Their sixty-four-year marriage was an extraordinary achievement. I bumped into Johnny in 1996 in an artist’s green room at the Sitges Film Festival. He peered up at me.*

‘Oh, Stephen. Do you know something? This is the first time Mary and I have spent a night apart since we were married.’

Astonishing. I once asked him what the secret of so strong a marriage might be.

‘Oh, it’s very simple,’ he said. ‘We behave like naughty teenagers who’ve only just met. I’ll give you an example. We were at a very grand dinner a couple of years ago, and I scribbled a note saying, “Cor, I don’t half fancy you. Are you doing anything afterwards? We could go to my place for some naughty fun …”, something like that. I summoned a waiter. “You see that ravishing blonde at the table over there?” I said, pointing towards Mary. “I wonder if you’d be good enough to hand her this note?” I was then rather horrified to realize – my sight was just going at this stage, you have to understand – that he was handing the note to Princess Diana. She opened it, read it and with her eyes followed the waiter’s pointing hand back to me, squirming in my seat. She smiled, waved and blew a kiss. Oh dear, I did feel a fool.’

Two events gave me especial delight during my years of friendship with Johnny. One was the good fortune I had in spotting that Christie’s were selling an old dressing gown of Noël Coward’s. I won the auction and gave it to Johnny on his eightieth birthday. He remembered Coward wearing it, and owning it gave him a remarkable amount of pleasure, which in turn, of course, gave me a remarkable amount of pleasure.

The second event took place on a freezing winter’s day in the grand old house Luton Hoo, former seat of the Marquesses of Bute and latterly the diamond magnate Julius Wernher, much of whose famous Fabergé collection was stolen from the house in a daring motorcycle raid. I was using it (some time after this burglary) as a location for scenes for the film Bright Young Things, an adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s second novel, Vile Bodies. I tentatively asked Johnny one day whether he would consider playing the part of Old Gentleman at a Ball. He immediately consented. I explained that what I wanted him to do in his scene was to spot Miles, a fey young man played by Michael Sheen, apparently taking a pinch of snuff from a small silver box. Miles would offer the old gentleman a pinch of this ‘snuff’, which was peculiarly white for milled tobacco, and then resignedly allow him to take more and more in odd moments when we returned to them as the ball progressed. Johnny was very excited to be playing his first drug scene so late in his life and took it, as he did all his work, very seriously. Though just about stone blind and in a large chilly house, he asked for nothing extra. We had made up a small interior tent for him, however, which we furnished with a day bed and five-barred electric heater.

A few years later Johnny lay dying in a new house in Denham Village (The Gables I think it was called), up the road from Hills House, where they had spent so many years. I went to visit him. He had a chest infection and couldn’t really speak, but I sat and held his hand. I had brought with me an iPod, on which I had uploaded as many Noël Coward numbers as I could find. He was dressed, as he liked to be, in a velvet jacket, his KBE and CBE medals proudly attached to his chest. I put the iPod down by his side and gently pushed the earbuds in. As I heard Coward’s voice crooning ‘I’ll See You Again’, I saw his mouth form a smile and tears leak from the corners of his eyes.

Back at the Savoy Hotel a few days after the Mills–Branagh dinner party I am waiting at six in the morning for my car to take me to Wrotham Park for the day’s filming on Peter’s Friends. I find myself chatting to Arturo, one of the linkmen.

‘You a fan of Frank Sinatra, Mr Fry?’

‘Am I? You bet I am.’

‘Ah, well. He’s coming to stay with us today.’

‘You’re kidding!’

On the ride up to Hertfordshire I rehearsed what I’d say if I bumped into the great man. Ol’ Blue Eyes. The Chairman of the Board. The Voice.

The filming, as it does, went on and on and on and on and on. It must have been past midnight before I drew up again at the Savoy. Arturo opened the door for me.

‘That was a long day, Mr Fry.’

‘Looks like it was for you too.’

‘Just started my shift, sir. Now, why don’t you follow me? Something I’d like you to see.’

Baffled and faintly irked – all I could think of was bed – I trailed after Arturo along the passageway that led, and still does, to the American Bar. We went down the steps, and Arturo pointed towards a man sitting in a pool of light, head bowed over a crystal lowball glass, backlit cigarette smoke ribboning up. A living album cover.

‘Mr Sinatra, I’d like you to meet Mr Fry, a long-term guest.’

The man looked up and there he was. He pointed to the chair opposite him.

‘Siddown, kid.’

‘Kid’. Francis Albert Sinatra had called me ‘kid’. It reminded me of the moment in Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers when Spike Milligan says in a stunned, reverent voice, after Charlton Heston has grasped his wrist and whispered him into conspiracy against his wife (Raquel Welch), ‘The Cardinal has taken me by the hand and called me friend!’

I think I had about three minutes alone with Frank before the room was filled with old friends and I found myself pushed to the edge of the party. But it was enough, and I wound my way back to 512 as one in a holy dream.

A few days later I saw Arturo on duty again. I pumped him by the hand and pushed a fiver on him.

‘As long as I live I will never forget that moment, Arturo. What a favour you did me. I can never thank you enough.’

‘It was my pleasure, Mr Fry.’

‘Is he still here?’

‘Left this morning. Quite funny actually.’

‘Oh yes?’

‘Well, just before he got into his car for the airport he gave me a roll of cash. Great thick roll it was. “Thanks for a terrific stay, Arturo,” he says. “Well, thank you very much, Mr Sinatra. Always a pleasure for us to have you at the Savoy.” “Tell me,” he says, “is that the biggest tip you’ve ever had?” I look down at the money. Huge roll of twenties and fifties it was. “Well, as a matter of fact, sir, no it isn’t,” I says. He looks most put out. Most put out. “Well tell me,” he says, “who gave you a bigger one?” “You did, sir, last time you stayed,” I says. He got into the car, laughing his head off.’

‘And next time he stays you’ll get an even better tip,’ I said.

‘Ooh, the thought never crossed my mind,’ said Arturo.