Outmaneuvered and Outflanked

With a lightning strike through the heart of France, the Germans forced the Allies to retreat

MARCHING FORWARD The 51st Highland Division of the British Expeditionary Force crossed a drawbridge into Fort de Sainghin on the Maginot Line in November 1939.

The Nazis’ Daring Plan

Beset by snow and a plane crash, the Germans redirected troops invading France through the dense Ardennes Forest

Hitler planned the invasion in consultation with key strategists, such as General Albert Jodl, to his left.

Hitler’s generals, disappointed with the German performance in Poland, were reluctant to rush into France in September 1939. Hitler, convinced that the passage of time favored the Allies, disagreed. In October, he ordered the High Command to formulate an invasion plan for November 12. The proposal the officers presented, known as Case Yellow, called for a three-pronged deployment of German troops. The main thrust of the onslaught would be through the Gembloux Gap in Belgium, across a wide, flat plane that offered favorable terrain for the bulk of Hitler’s troops. A smaller force would drive north to secure the Dutch coast, and a third would strike the Maginot Line farther south to prevent the French from dispatching reinforcements to the main point of the attack in Belgium. Hitler preferred a less conventional strategy but agreed to proceed.

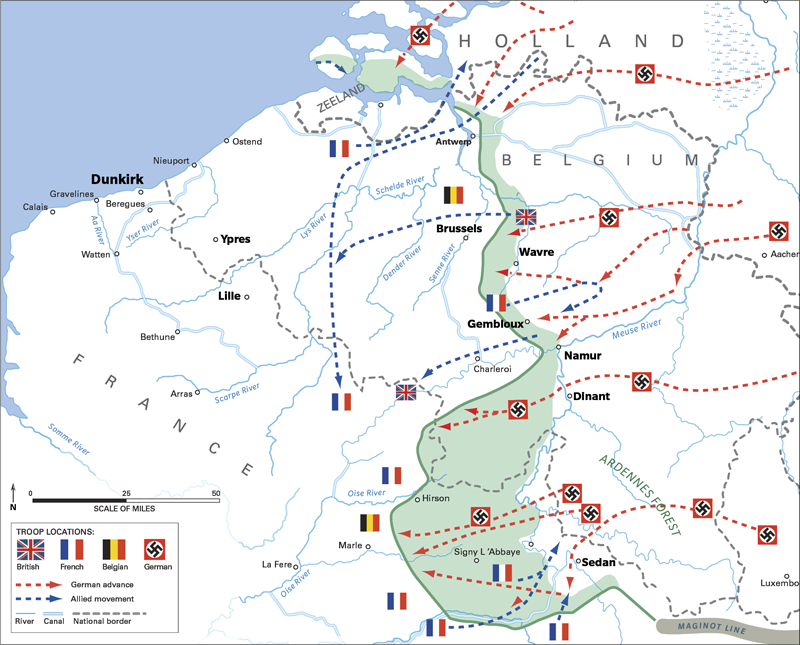

Several developments doomed Case Yellow while inadvertently benefiting the Germans. First, there was the weather, with snow, cold temperatures and limited visibility forcing multiple delays in November and December. Then, on January 10, 1940, a plane carrying a German officer with the invasion plans in his possession crash-landed in Belgium and the officer was captured. With Case Yellow fatally compromised, Hitler embraced the approach of Erich von Manstein, the chief of staff to General Gerd von Rundstedt, who had been pressing for months for a surprise invasion through the Ardennes Forest north of the Maginot Line but south of the Gembloux Gap. Von Manstein, along with Panzer commander Heinz Guderian, was convinced that, with proper planning, the Panzer divisions could make their way through the forest in three days. From there, they could cross the Meuse River and surprise the French at Sedan, opening the way for a lightning strike through the heart of France. Franz Halder, the chief of the general staff, had reservations, but a private meeting between von Manstein and Hitler cemented the deal, and the plan, known as Sichelschnitt (Sickle Cut), became the official German strategy. Seven of 10 Panzer units, under von Rundstedt’s command, would be devoted to the charge through the Ardennes. A secondary attack to the north and including the Gembloux Gap and the Dutch coast would be launched under General Fedor von Bock. Von Rundstedt, somewhat skeptical of the Panzers’ maneuverability, briefly considered shifting the attack through the Ardennes to an infantry-led assault, but Guderian and Halder convinced him otherwise. The attack was set for May 10.

The Allies’ plan for defense, largely formulated by French commander-in-chief Maurice Gamelin, assumed the Maginot Line was impregnable and that any move through the Ardennes Forest would be too time-consuming, delaying the Germans for seven to nine days. That meant the most likely route for a German invasion would come through Belgium and almost certainly the Gembloux Gap. With that in mind, Gamelin approved the so-called Dyle (or D) Plan, which placed the most capable French forces inside Belgium, along the Dyle River from Antwerp to Wavre and through the Gembloux Gap to Namur. Gamelin compounded this error by assigning another respected unit, the mobile 7th Army under General Henri Giraud, to charge up the Belgian coast to Holland to keep the Dutch in the conflict in support of the Allies.

EARLY SUCCESS

The German invasion began as scheduled, when paratroopers air-dropped into Holland. A single Panzer division soon charged through the country to back them up. The Luftwaffe planes transporting the paratroopers sustained heavy losses, but the Dutch surrendered in just four days. The victory provided the Nazis with the air bases they needed to extend their dominance to the skies over Belgium and France.

The rest of the German plan worked equally well. The German surge into Belgium provoked the French, supported by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), to move to designated positions along the Dyle River. Both armies were confident they were meeting the primary thrust of the German effort. Meanwhile, three Panzer divisions made their way through the Ardennes, covering the 85 miles to Sedan and the Meuse River on the border of France in just 57 hours, well under Guderian’s three-day projection, and much faster than the French estimate of at least a week. A little farther north, two Panzer divisions under Erwin Rommel navigated even more difficult Ardennes terrain and arrived at Dinant on the Meuse, southeast of Brussels, at about the same time. On May 14, assisted by a heavy aerial bombardment, the motorized infantry regiments of Guderian’s Panzer divisions forced three crossings over the Meuse River near Sedan. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the French Armée de l’Air attempted to destroy the bridges before the Germans could cross, but their aircraft, with insufficient support, were decimated—including 40 of the RAF’s 71 bombers—by anti-aircraft weaponry. With their morale shattered, the French troops fled their positions near the Meuse in droves.

CHARGE INTO FRANCE

Once the bridges were secured, Guderian and Rommel were under orders to consolidate their positions and wait for the infantry divisions. Instead, the two commanders charged after the retreating French troops, executing what some historians consider the first example of blitzkrieg. The daring maneuver showcased the Panzer divisions’ speed: soon Guderian was in Marle, 60 miles from Sedan, and Rommel was across the Sambre River, some 60 miles from where he crossed the Meuse at Dinant. That left the infantry far behind, creating a gap that might have offered the Allies an opportunity to split the German forces. But the French troops in the north, unaware of the situation, were unable to capitalize on it.

The Allied leadership, with limited options, responded poorly. The motorized divisions fighting the German advance through the Gembloux Gap in Belgium could have quickly retreated south to defend Paris, but such an action would have left 30 nonmotorized infantry divisions with inadequate defense against the Luftwaffe and a Panzer advance. Communication between the Allied commanders, not terribly smooth to begin with, broke down completely. On May 19, General Edmund Ironside, British chief of the Imperial General Staff, arrived to confer with BEF commander Gort at his headquarters in Lens, about 50 miles southeast of Dunkirk. Gort informed Ironside that he had received no orders from French General Gaston Billotte, the commander of the French Northern Army Group, in eight days. Disturbed by this report, Ironside visited Billotte and found him “in a state of complete depression,” he later wrote. “No plan, no thought of a plan. Ready to be slaughtered. Defeated at the head without casualties . . . I lost my temper and shook Billotte by the button of his tunic. The man is completely beaten.”

While the Allies dithered on May 17 and 18, the Germans repaired their tanks, rested and prepared for their next step. There seemed to be little threat from the demoralized French troops to the south. Seven of the nine divisions of the BEF were working their way back to the Scheldt River, leaving their right flank exposed to the 3rd and 4th Panzer divisions. Soon the Germans had isolated the British, the French and the remaining Dutch and Belgian forces, in the north. A last-gasp effort to break out by General Maxime Weygand, appointed by French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud to replace Gamelin, failed. The German vise tightened.

EARLY DAYS German tanks rumbled through the village of Malmedy, Belgium, on their way to France.

RAPID DEPLOYMENT German Panzers advanced through Belgium and to the Meuse River in France more quickly than even the Nazis anticipated.

COSTLY VICTORY After decimating the Dutch Air Force, the Germans dropped paratroopers near the airfields in De Kooy, Amsterdam and The Hague. It took just four days for the Nazis to declare victory, but they suffered 8,000 casualties in the process.

PREPARING TO FIGHT Outfitting the British Expeditionary Force to fight the Germans took almost a year, from the declaration of war in September 1939 until May 1940, when hostilities began in France. Even so, many of the troops were ill-equipped and only minimally trained.

Rapid Advance

Between May 10 and May 16, German forces, particularly their fast-moving Panzers, charged through Belgium and the Ardennes Forest and—as shown by the green shading—advanced some 50 miles into France.

FOREST TO RIVER Germany entered the war with more than half a million horses, many of them for infantry units. Before the invasion of France, Nazi soldiers crossed a river in the Ardennes Forest.

Once the advance Panzer divisions had fought their way across the Meuse, the following slower-moving infantry units forded the river in any way they could.

HEINZ GUDERIAN

The Genius of the Panzer Division

“FAST HEINZ” Guderian pioneered the development of reliable radio communications between tanks.

THE MAN most responsible for the development of Germany’s Panzer division was General Heinz Guderian. Outspoken and opinionated, Guderian had served in the infantry during World War I and experienced firsthand the stalemate that resulted from large, immobile armies dug into fixed positions. Between the wars, he studied motorized combat and pressed for the development of fast, maneuverable light tanks. He also conceived of the Panzer divisions, the rapid-strike forces equipped with tanks, infantry and support services. Teamed with the Luftwaffe, the Panzers executed Germany's blitzkrieg tactics in Poland and France. The divisions maneuvered so quickly that Guderian earned the nickname Der schnelle Heinz—“Fast Heinz,” sometimes translated as “Hurrying Heinz.” During the later course of the war, he was the German general most willing to disagree with Hitler, breaking with several of the German leader’s strategic decisions, and he was dismissed twice. After the German surrender, Guderian was held as an American prisoner of war for nearly three years, but no charges were ever brought and he was released in June 1948. He became a regular participant in meetings of British veterans, where he shared in discussions about the battles and strategies of World War II. Guderian died on May 14, 1954.

ERICH VON MANSTEIN

Mastermind of the Ardennes Strategy

IN AND OUT OF FAVOR Later in the war, Manstein was a key strategist during the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the sieges of Sevastopol and Leningrad.

ERICH VON MANSTEIN, one of Hitler’s most brilliant strategists, seemed destined to serve in the military. The tenth child of a Prussian aristocrat, Manstein was adopted at birth by his mother’s childless sister and her husband. Both his biological and adoptive fathers were military officers, as were 16 other relatives. Manstein served with distinction on both the eastern and western fronts in World War I and was an active participant in the rearmament of Germany in the period between the two wars. When the Nazis invaded Poland in September 1939, Manstein was serving as the Chief of Staff to General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group South (sometimes called Army Group A), one of the two German forces that charged into Poland.

When von Rundstedt learned of his rival Franz Halder’s plan to invade France, he asked Manstein to formulate a more daring alternate. In consultation with Panzer General Heinz Guderian, Manstein concluded that an attack through the Ardennes Forest would take the Allies by surprise. He also believed that a secondary offensive through Holland and Belgium, operating as a feint, would draw the best Allied forces north. That would pave the way for the Germans to charge through the Ardennes, move west toward the English Channel and trap the Allies on the coast of northwest France. Halder ridiculed the strategy and had Manstein transfered east to command the 38th Army Corps.

Two officers on Manstein’s staff contacted Hitler’s personal attaché and persuaded him to brief his boss on the proposed plan. Intrigued, Hitler brought Manstein to Berlin to explain the strategy further. After the meeting, he expressed admiration for Manstein's intelligence but wariness of his arrogance. “Certainly an exceptionally clever fellow,” he said of Manstein, “with great operational gifts, but I don’t trust him.” The Nazi leader’s comments after the success of the Ardennes plan were more effusive: “Of all the generals, with whom I spoke about the new attack in the West, Manstein was the only one who understood me!” Manstein’s stock with Hitler fell again later in the war, after a series of disputes, and on March 30, 1944, Hitler relieved him of command.

What They Brought

Each force had its strengths, but neither Britain nor France could compete with the German Panzer divisions

THE TROOPS

Hitler, in a letter written on May 25, 1940, described the British soldiers as “very brave and tenacious,” though “wretchedly commanded.”

All three nations began the conflict in France with a mix of well-prepared veterans and hastily trained recruits. The Germans gained an advantage from their experience in Poland, where they were able to test the blitzkrieg tactic—a lightning-quick attack with tanks and infantry supported by overwhelming air power. More than three quarters of France’s 81 infantry divisions and 80 percent of Germany’s 135 divisions relied on horses, which had to be fed and cared for, a requirement that proved a logistical nightmare. The British had 10 motorized divisions and three support divisions and hence were less reliant on horses than either the Germans or French.

THE TANKS

The French SOMUA tanks were almost impervious to German shelling, but there were not enough of them.

The German Panzers, especially the Panzer I and II, were vulnerable to artillery attacks and anti-tank weaponry. But by almost every other measure, the armored Nazi vehicles and the units they accompanied surpassed those in the Allies’ arsenal. The Panzers were more flexible than both the French SOMUA tanks and the British Matildas. There were also more of them—2,400 total for the Germans compared to 1,000 truly functional tanks for the Allies. And the Panzer divisions were exceptionally sophisticated. Each included 250 tanks, mobile workshops to repair damaged equipment, a motorcycle battalion, an artillery regiment, motorized infantry and a group of engineers known as pioneers, who deployed a range of specialized tools including mine-detecting devices, flamethrowers and bridge-building equipment.

THE PLANES

The German Do 17 bombers saw limited action in Dunkirk and were soon phased out in favor of the more powerful Junkers.

The Luftwaffe entered the war with more than double the number of planes in Allied hangars—2,800 bombers and fighters compared to 1,300 for Britain and France. The two primary models, the Stuka bombers and the Messerschmitt fighters, were effective in battle—fast, maneuverable and well defended—though the Messerschmitts needed skilled pilots to operate them properly.

The RAF was more successful against the Luftwaffe at Dunkirk than the bombing of the beaches suggested. Even with a fleet of mixed quality, the British downed 244 German planes over the nine days, while losing 177 of their own. Their best performers were the Blenheim bombers and the Hurricanes. Less successful were the Fairey Battle bombers, slow and difficult to maneuver. Spitfire fighters, which proved vital to later British victories, participated in only limited numbers during the early days in France.

The main fighter plane for France, the Morane-Saulnier, was outdated and outmatched. Only the skill of French pilots enabled them to compete with the Messerschmitts at all.

THE GUNS

Each of the three armies featured one standard-issue weapon distributed almost universally throughout the ranks

Germany

German MP40 submachine gun

Accurate, powerful and reliable, the Karabiner 98k bolt-action rifle was carried by the German infantry in every theater of World War II. First developed in 1935, the Karabiner 98k was rated as accurate up to 550 yards and could be adapted to include a telescopic sight, enabling snipers to fire at targets nearly 875 yards away. Other weapons widely distributed among the German troops included the Gewehr 43 semi-automatic rifle and the MP-40 submachine gun.

Great Britain

British Bren Mk 1 light machine gun

An iteration of the Lee-Enfield .303 bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating rifle was carried by British soldiers from 1895 until 1957, a tribute to the weapon’s reliability and effectiveness. Its Lee bolt-action and detachable 10-round magazine allowed a skilled and well-trained soldier to fire 20 to 30 targeted rounds per minute, making it the fastest bolt-action combat weapon in the war. The gas-operated Bren light machine gun was used widely as well. Using the same .303 ammunition as the Lee-Enfield, it could fire 480–540 rounds per minute.

France

French Lebel M 1886

The primary French infantry weapon was the Lebel M1886 8mm bolt-action rifle, in service since before World War I and somewhat unwieldy due to its length and weight, but still effective. The lighter, more rapid-firing MAS-36, intended to replace the Lebel, was not in mass production in May 1940, but many of the troops had nonetheless received them. Neither weapon was considered as versatile or effective as the Lee-Enfield or the Karabiner. The MAS-38 submachine gun was first used in combat during the battle of France and could fire 700 rounds a minute and had an effective range of up to 100 meters.