Introduction

I keep thinking of myself as some sort of displaced philosopher. The issue of displacement is, in any sense, crucial to my work. According to Gilles Deleuze, philosophy has mostly to do with inventing concepts. In that sense, I am not a philosopher: I do not invent concepts, but I try to displace them. For instance, the concept of structure is of great interest, when dealt with in artistic terms. I first became interested in architecture because architecture provides us with an open series of structural models.

—Hubert Damisch1

The following essays, written between 1963 and 2005, represent Hubert Damisch’s forays into architectural theory. Organized roughly according to the chronology of their subject matter, they span the period between the Renaissance and the present, a period of architecture’s emergence as a “discipline” with all the attendant problems of “origin” (Noah’s Ark or Adam’s House?), “structure” (abstract model of relations between the elements, or supporting framework?), “meaning” (communicative sign or silent system?), and, with increasing industrialization, “material” (building fabric or essential nature?).

These questions and more permeate Damisch’s reflections, which are not so much couched in terms of theoretical pronouncements or historical exegeses but rather read as what he calls in another preface “a set of exercises.” In the case of the previous collection, under the titleSkyline, Damisch’s “exercises” were primarily (as his subtitleThe Narcissistic City indicates) concerned with the imaginary, symbolic realms explored by psychoanalysis. In the present collection, the preoccupation is less with Freud or Lacan (although the presence of a modern subject is always lurking close to the surface) as it is with the general idea of “structure,” construed both physically and mentally and analyzed in terms introduced by structuralists both anthropological and linguistic, from Claude Lévi-Strauss to Roland Barthes.

However, Damisch differs from many who have tried toapply structuralism to architecture, forcing architecture to conform to the combinatory rules of language, and from those who wouldread architecture as a language, with the result that its elements are isolated as so many words and phrases. His aim is both more philosophical (to think of architecture in another key than that of its internal disciplinary forms) and less systematic (as he constructs a kind of parallel universe for architectural thought). Here, the conjunction that appears often in his titles—with—is symptomatic: His aim is not to treat architectureand philosophy, structure, semiology, nor to develop a philosophyof architecture, but to discuss, to formulate a discourse of architecturewith philosophy. The title of one of the essays in this collection, “Ledoux with Kant,” thus does not imply that Ledoux ever read Kant, or that his architecture might be analyzed according to Kantian aesthetics, but that the juxtaposition of the two might reveal important and hitherto unexplored questions. In this sense, architecture would be as important for the analysis of philosophy as philosophy would be for architecture.

Philosophy and architecture have had an uncertain partnership since Plato’s excoriation of Pericles’s Acropolis as a mark of Athenian decadence and Socrates’s indifference; he who by all accounts was the son of a stonemason and trained as one himself was only concerned to make sure that the “builder” stuck to his trade and was refused full citizenship with all the other trades. It was left to Vitruvius, hardly a philosopher, to piece together a few fragments of Greek wisdom into a story of “origins” (from wood to stone) and a theory of design (concinnitas,firmitas,venustas) that has continued to haunt architecture. If, since then, architecture was noticed in philosophical discourse, it was more as a useful analogy—its apparent “rational” structure a paradigm for philosophical argument (Descartes) or as an abstract model for construing “judgment” (Kant).

It was not until the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and with the still problematic inclusion of architecture (a mixed art) among the other (fine) arts within the subgenre of philosophy named “aesthetics” by Baumgarten, that architecture entered into discussions of origin and ontology with its own supposed autonomy. Thus, Hegel saw it as the first, symbolic step toward philosophical emancipation, rapidly to be overtaken by sculpture, painting, and poetry. Schelling, following the historiographical line of progress outlined by Hegel, assessed architecture in terms of its internal and implicitly external forces; Nietzsche used its decline and fall from grace as an expressive art as a sign of the loss of primal rhetorical energy; and Heidegger attempted to resituate its origin as an indestructible monument to presence.

Meanwhile, nonphilosophers and architects, from the abbé Laugier to Viollet-le-Duc and Gottfried Semper, began the process of reformulating the Vitruvian notion of origin, through ever more sophisticated versions of structural and ornamental history, with the legacy to the twentieth century of a bifurcated discipline caught between the literal model of structure (the reinforced concrete Maison Dom-ino or the Miesian steel frame) and a vague, quasi-Neoplatonic version of typology that put this model to work in various programmatic contexts.

In this discursive impasse, one that was replicated in the many other disciplinary discourses analyzed by Michel Foucault, the disruptions forced by Derrida and Lacan into the notion of structure and sign opened the way to a rethinking of the very idea of a “structural” model, whether of origin, center, or foundation—a rethinking paradoxically founded on the refutation of the model of structuralist anthropology proposed by Lévi-Strauss. In “Structure, Sign, and Play” (1965), Derrida highlighted the dilemma of “doing without the concepts of metaphysics in order to shake metaphysics,” of questioning the notion of a centered structure and a central signified when no syntax or lexicon exists outside the history of metaphysics: “We can pronounce not a single destructive proposition which has not already had to slip into the form, the logic, and the implicit postulations of precisely what it seeks to contest.”2 This problematic, which Derrida found to be sustained in the anthropology of Lévi-Strauss, was (slowly enough) taken on by critics of the mythic structures of architecture. Gradually, through many interesting but properly illegitimate misreadings, the equally mythic model of “Deconstructivism” was born—but not without the intervention of a second destruction, one operated by Lacan on the notion of the subject, one already destabilized, as Derrida notes, by “the Freudian critique of self-presence, that is, the critique of consciousness, of the subject, of self-identity and of self-proximity or self-possession,”3 and that, extended by Lacan, displaced the apparently fixed position of the viewing subject.

Asked by Denis Hollier some years ago how he might define himself (“Historian of art? Antihistorian of art? Theorist of art? Philosopher of art?”), Hubert Damisch referred to two major influences on his education: the phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty and the art historian Pierre Francastel. In Merleau-Ponty’s seminars, he encountered “the question of the unconscious,” the “perception of history,” and “structuralism,” as it was then being developed by Lévi-Strauss. From Francastel, he absorbed the social history of art and an interest in art and technique. In a sense, we can read Damisch’s subsequent work—on painting, film, and architecture—as a long and complex meditation and response to these two thinkers, in a vein, as he states, that explores as much what they rejected as what they put forward. In this reflection, the problematic that emerged for Damisch was “the perception that there are questions that emerge from within the historical field that can be posed in historical terms but that history itself cannot answer. That’s what absorbed me: how is it that history can pose questions that it nonetheless cannot answer?”4

Another answer would perhaps be that, as a philosopher concerned with attacking fundamental questions of the arts, Damisch has taken a route that avoids the usual traps of the field. Rather than use the various arts as analogical props for thought (Descartes on architecture, for example, as a model of rational argument), or absorbing them in an attempted general theory of aesthetics (Baumgarten, Schelling, Hegel, etc.), he is engaged in unpacking the different practices from the inside, so to speak, as if they possessed their own peculiar form of philosophical thinking—as if, as he has often said, they “thought themselves.” Which would be one way of saying that his analysis is truly structural—and constructing a structural model is for him a primary task of the analyst. However, such a model, as he has emphasized again and again, is not a static and unmoving object in itself; it is rather an instrument used todisplace the object—in Damisch’s terms, atheoretical object: “A theoretical object is something that obliges you to do theory; we could start there. Secondly, it’s an object that obliges you to do theory but also furnishes you with the means of doing it. . . . Third it’s a theoretical object because it forces us to ask ourselves what theory is. It is posed in theoretical terms; it produces theory; and it necessitates a reflection on theory.”5 Once constructed, however, this theoretical object itself produces effects; the very act of producing it “displaces” the objects of analysis.

An observer of clouds, miasmas, uncertain perspectives, of the disturbing psychic undercurrents of beauty, and the heterogeneity of vision, Hubert Damisch would seem to be an unlikely theorist of architecture. Something as firm, formed, stable, fixed, and unshifting as architecture would hardly appeal, let alone respond, to the interrogation of theinforme, the unseen, and the unthought—the subjects, indeed, that are habitually attributed to Damisch. Yet, from the outset, without much fanfare, and with no treatise or book to advertise the fact, this detective of the elusive has been elaborating, through incisive and regularly published essays, a theory of architecture. Rather, on the surface at least, he has been interrogating other, historical theories of architecture in such a way that, if read systematically and preferably consecutively in the chronological order of their subject matter, an emergent theory of architecture might be discerned—one that, while not pretending to operative or instrumental status, nevertheless construes the subject in a radical frame, a frame that if allowed will shift the nature of architectural understanding or, as Damisch prefers, architectural “thinking.”

“What isthinking in painting, in forms and through means proper to it,” asks Damisch in another context, that of his investigation of another “origin,” that of perspective.6 In a work completed contemporaneously, the preface to the French edition of Emil Kaufmann’s bookVon Ledoux bis Le Corbusier, Damisch poses the same question, but to architecture, precisely through the “forms and through means proper to it.”7 In the case of painting, Damisch has demonstrated thatperspectiva artificialis allows the painter not simply to “show” but also to “think” by means of an apparatus that is epistemologically akin to the sentence in language. Perspective organizes “point of view, vanishing point, and distance point, and the other corollary points designating here, there, and over there—which is sufficient to make it possible to speak, again nonmetaphorically, of a geometry of the sentence that would have its analogue in the figurative register.” In this sense, perspective, like the sentence, “assigns the subject within a previously established network that gives it meaning, while at the same time opening up the possibility of something like a statement in painting.”8

What, then, might provide such an apparatus for architecture, one that might allow it tothink and even, despite its supposed abstraction, to make a statement something akin to a sentence? Certainly, the “origin” of geometry, in the same way as the “origin” of perspective for painting, provides a partial answer for architecture. Even as Greek geometry purified itself (in Husserl’s terms) of all anthropomorphism, so architecture in Ledoux’s hands purified itself of organic metaphor, bodily embodiment, and the imitation of antiquity. The process of “autonomization of form” construed columns as cylinders bereft of human proportions, villas as cubes denied all Palladian attributes save that of their diagrammatic nine-square plans, and houses that “spoke” solely through geometrical alphabetization. Beyond this specifically eighteenth-century model, Damisch develops a set of conditions that reach into the posthistoricism of the late twentieth century and that derive not from Ledoux but from two other, earlier studies of instaurational moments: that of Alberti and that of Viollet-le-Duc. In both cases, Damisch is concerned with structure—not exactly the material structure of a building, although this too, but structure in the sense of thought. Architectural thinking is here carried out through the idea of structure and turns on the Albertian problem of “column” and “wall.”

Interrogating the idea of “structure” in Alberti’s treatise, by way of distinguishing between the idea ofcontinuity signified by the word in Vitruvian and Roman usage and that ofdiscontinuity—of the assemblage of discrete elements—implied by the more modern usage after Viollet-le-Duc, Damisch confronts the apparent paradox of Alberti’s eloge of the column as “the principal ornament of architecture” and his limitations on its use with respect to the wall and its continuity. Similarly, in his article on Viollet-le-Duc’s essay “Construction,” it is not so much the material structure that Damisch seeks, but precisely the mechanism in thought that would, without rupture, bring theoretical and physical structure together within the same architectural thought.

Damisch, due as much to his interest in “column” as to his interest in “structure,” has been called a structuralist. This would be so, certainly, if by “structuralist” one means “an individual engaging in attention to the rational structure of thought, of discourse, and of the relations of one proposition to the next.” It would be less true of that Damisch who, in parallel with Lacan and Derrida, and in sympathy with both, interrogates the hidden underpsyche of architectural thought. However, it is also the underneath, that “crypt” of writing investigated by Derrida, that will of itself deny the authority of every statement, every monument to certainty and belief. It is also that underneath, spoken of by Lacan, that remains in the psyche long after the mirror has apparently constituted the self as a whole, structured the world as an imago, formed a supposed whole out of part objects. It is this “whole,” this surface unity, that Damisch cannot in the end find satisfactory as an explanation for the perfection of an architectural object, itself in classical theory a stand-in for the human body and its qualities.

Which is why, in a later iteration of his own (hidden) architectural theory, Damisch finds solace in the fact that a building, like a painted image, can be a cloud: formless, yet structured and technologically sound; Viollet-le-Duc welded to Turner, the classical to the modern, transformed in Diller + Scofidio’s Blur pavilion for the Swiss Expo 2002 into a shifting, nebulous,informe architecture—an architecture that, finally, will speak of its own internal contradictions.

Anthony Vidler

New York City

March 2015

0.1

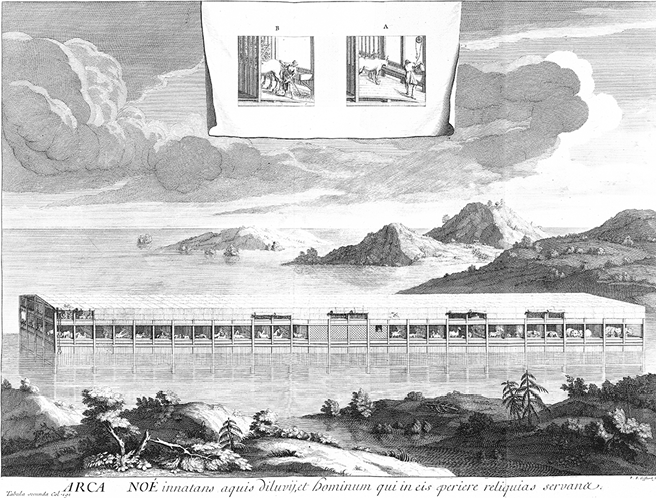

“Arca Noé.” From Bernard Lamy,De tabernaculo foederis, de sancta civitate Jerusalem, et de templo ejus (Paris, 1720), facing page 191. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.