2 The Column, the Wall

If we are to believe Viollet-le-Duc, the Renaissance, nourished as it was on Vitruvian literature, had nothing but contempt for structure; the classical architect simply supplied the form in the shape of a drawing, and the mason translated it as best he could and as the materials at his disposal allowed, a process that paved the way for all kinds of mistranslations.1“Tota res aedificatoria lineamentis et structura constituta est”:2 the first great treatise on architecture of modern times, Alberti’sDe re aedificatoria, takes its point of departure from an explicit distinction betweenform andmatter, if not betweendesign andstructure. But how are we to understand “form” or “structure” in this instance? When one speaks of structure today, it is in terms of assembly, a combination of discrete elements, and consequently of discontinuity, whereas the definition of form, understood in its unity and essential coherence, implies continuity. We are inclined, since Viollet-le-Duc, to think of structure in terms of frames and articulated, discontinuous systems. Yet the Romans, and Vitruvius above all, would have associated the wordstructure with the continuity of masonry—brick and stones set in mortar to ensure its cohesion.3

Was Alberti, then, simply the precursor, still hesitant and sometimes feeling his way, of a classicism that was to become only truly self-aware in the sixteenth century? And was his treatise, in the end, less important theoretically than historically, as Anthony Blunt claimed, with its historical importance largely due to the fact that it contained the first modern exposé of the doctrine of orders and the rule of proportions? Whereas Brunelleschi chose to use the column in a deliberately antique spirit (but with the greatest liberty and with little respect for ancient canons), Alberti developed the principles of a rigorous classicism based on a deeper knowledge of antique monuments. Beyond this, he also had the distinction of having recourse to the orders in order to resolve the compositional problem of multistory facades—linking and superimposing columns and entablatures in order to organize them in a grid, the clarity of which was to become an element of the best Tuscan tradition. Despite this, we still had to wait for the second half of the sixteenth century to see the principles and rules he formulated enter into architectural practice: the Doric column only made its appearance in 1509, in Bramante’stempietto, and Italian architects—to say nothing of those further afield—were to hesitate for a long time before employing the orders in codified form.4

Art historians have accounted for the delay between Alberti’s first formulation of the classical norms and their systematic use in practice by the need to discriminate between the value of the column as a constructive and a decorative element. Doubtless, the column first had to lose its place as the unique architectonic element (as it was for the Greeks) before it could be accepted as one of the privileged terms of what was to become the language of ornament.5 The use of orders applied to a wall clearly derived from the Roman tradition, Alberti himself having acknowledged that it was ofLatin, evenItalic, rather than Greek, origin. Yet if it is clear that he had intended to create a doctrinal work, what does it mean for the theoretical foundations of a doctrine to be based on Roman models? In fact, the brief and deliberately cursory exposition of the doctrine of the five orders appears only in Book Nine of his treatise; the preceding books were devoted to a critical analysis of the elements of the art of building, as Alberti attempted to put his observations into good order and—as his first French translator, Jean Martin, put it—“to give to each thing the proper reasons concerning the matter.”6 This poses a problem: could Alberti have known enough to press his analysis far enough to expose the contradiction inherent in the classical doctrine and in the use of the classical orders in the context of what is now commonly understood aswall architecture?

Rudolf Wittkower was the first to readDe re aedificatoria without attempting to trace early signs of the classical doctrine, following instead the reasoning that led Alberti to distance himself from the Roman ideal on one essential point: the use of the column as an element of an order applied to a wall.7“In the whole art of building the column is the principal ornament,” Alberti wrote. “There is nothing to be found in the art of building that deserves more care and expense, or ought to be more graceful, than the column.”8 These formulae seem to be completely in line with the first Florentine Renaissance and with an architecture that Brunelleschi had understood to be defined by the column as well as the dome.9

Yet Alberti considered the column from a very different perspective than that of Brunelleschi. He criticized the early Christian basilica for its light wooden roofing supported by rows of slender columns (which were also often reused, introducing an additional factor of “disorder”), which appeared to him to contradict the “dignity” of sacred building and against which he set up the model of a vaulted building, the roof of which was to be supported by thick walls.10 He advocated the use of the classical orders to animate and break up the continuous surfaces (parois), the uniformity of which is tiring to the eye.11 All these theoretical assertions, formulated before their execution in his projects for the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence (in 1447) and Sant’Andrea in Mantua (in 1470), testify to a change of direction that would prove decisive for the evolution of architecture in the classical and/or the baroque period. Whatever Bruneslleschi’s taste in the treatment of surfaces, the projection of an articulated structural scheme on a neutral wall (paroi)—following the principles of early Christian architecture—in which the column in combination with the arch plays the leading role, seems to contradict the very principle of wall architecture associated with Alberti’s name. Does this mean that Alberti’s definition of the column necessarily implies abandoning the system outlined by Brunelleschi, one which Alberti himself was pleased to celebrate for its novelty, and the study of which—as much as that of the monuments of antiquity—strengthened his doctrine?

If we accept Wittkower’s interpretation of the passages inDe re aedificatoria devoted to the problem of the column, then it would seem that we have to accept that Alberti thought of architecture in terms of a continuous structure, in the Roman sense, and that he held the column to be an essentially decorative element and, as such, subordinate to the wall. His definition equating an order of columns with a wall that is pierced and open in several places12 seems to be a misinterpretation of the Greek system, in which the column is presented as a formal unit independent of, and diametrically opposed to, the wall. However, it is in fact situated in a direct line of descent that can be traced to architecture of the twelfth-century Tuscan Proto-Renaissance and the Late Imperial period, whose arcaded street facades and engaged columns provided Alberti with his model.13

Despite this apparently surprising definition, Alberti may have understood the true significance of the column and of the Hellenic orders better than any other architect of his time. Certainly, if the column is reduced to being a part of the wall, it is difficult to see how its cylindrical form could be justified. Yet if we consider not the engaged column but the freestanding, independent column, we find that, in accordance with an architectonic principle that he twice formulated in his treatise forbidding the discontinuity of superimposed members, Alberti rejects the idea of a square arch—which would itself be cut out, so to speak, from the mass of the wall—resting on a cylindrical support. Although he accepts the column as being a support for a horizontal architrave, Alberti nevertheless requires (except in the case of small-scale buildings) an arch to be regularly combined with a pier, whether or not engaged to half columns (as would Viollet-le-Duc). Otherwise, the “building” (construction)—as he puts it in a singularly “modern” way, thereby setting off a train of formulations that would turn out to be particularly productive—would be “false.”14 But in this strict distinction between the functions of the column and those of the pier, and in restricting the specifically architectonic value of the column by associating it with the entablature, does not Alberti show himself to be as much Greek as Roman? Hence Wittkower’s conclusion: if the emphasis placed on the wall is essentially Roman, then the limits placed on the use of the column are tied to the logic of the Greek system.15

What, then, is awall? What is the logic that defines and characterizes it? Beyond this, what is the logic that might be imposed on the building as a whole? It is clear that if there is a contradiction between column and wall, it arises at a level of coherence distinct from the strictly constructional, one related to the plastic properties that are irreducible to the simple mechanics of solids. But if the principles of combinatorial order that come into play at this level take on a logical value, are they in fact necessary, bound up as they are with the very nature of the wall (if there is such a thing as “nature” in this case)? In the absence of a portico set some distance from the wall, why would the pilaster be better suited to the wall than would the engaged column? And why should a wall present a rigorously flat surface purged of all accident? Then again, what is the origin of the Renaissance and baroque taste for facades with diamond-pointed rustication? Is a facing with cyclopean rustication and huge, rough-hewn blocks any closer to the “essence” of the wall than the smooth, whitish surfaces characteristic of Brunelleschi’s art? Brunelleschi could treat the inner walls of his basilicas like so many planes of projection, inscribed by the main lines of a space at once perspectival and architectonic; what was important for his design was that these walls be stripped of all material appearance so they could function as the imaginary support for the constructive and ordering activity of the mind.16 Yet, as the cyclopean facade of the Pitti Palace reminds us, there is nothing immaterial about the wall, and it is hard to see how a uniform roughcast would be better adapted to the nature or essence of the wall than would a treatment perhaps rougher but more revealing of the wall’s underlying structure.

More to the point, it seems as though an exaggerated respect for the planar quality of the surfaces implies a questioning of the wall itself, if not its negation. This is a paradoxical outcome to say the least, but one that we need to assess carefully if we want to understand the different modalities of wall treatments in their dialectical succession and of the use of the classical orders exemplified in the architecture of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In fact, it is not enough to characterize the architecture of Michelangelo or Palladio by pointing to the emancipation of the elements of the order and to the supposedly “tragic” contradiction between the decorative frame and the surfaces it defines. For—as we see on the lower floor of the vestibule of the Laurentian Library, where the coupled columns are set back from the plane of the wall, recessed in niches opened up in its thickness, and defined by thin perpendicular pilasters, or in the application of giant orders to the facades of Vicenza or Venice—the insertion of foreign bodies into the wall does not hold only negative consequences. The conflict between members and surfaces, their interpenetration, even their exchange of roles and functions, and the whole play of inversions and permutations, as well as of calculated ambiguities that could be characterized as baroque (or even as mannerist),17 only brings out more clearly the respective qualities of the wall and the elements of the order. On the contrary, the (partly imaginary) synthesis of frame and wall achieved by Brunelleschi, and after him by Alberti, implies the deliberate negation of the wall, whether considered in its materiality or in its continuity. Here, the emphasis placed on theplane of the wall in some way entails, to speak in phenomenological terms, its “neutralization”—its reduction to the status of an imaginary screen, a simple support for a plan—in the same way as Alberti’s metaphor of the window in his discussion of painting is meant to correspond to the nullification of the picture plane that once ensured its transparency.

Take the wall of Santo Spirito Church in Florence as it can be seen today, after the transformations that Manetti (under Alberti’s influence) contributed to Brunelleschi’s initial project. With its contradictory surface of columns and niches enclosing an illusory mass—a mass that is more like an empty shell—such a wall is in no way a natural given. The structure in which historians believe they see the system’s point of departure, far from being definable as a reality, is in this case the outcome of a cultural work that follows no deductive logic but rather reveals the largely regulatory, and consequently a posteriori, nature of a system like Alberti’s. In the final analysis, the difficulties arising from any attempt to reduce a given architectonic system to an elementary structure—whether of wall or partition, intersecting ribs or classical orders—depends on the fact that the structures revealed by analysis are not so much objective or technical as they are logical and perhaps semantic; in fact, it is impossible to treat any architectonic element while disregarding thevalue it assumes in the context of the system. Whether Roman, Carolingian, Brunelleschi’s, Alberti’s, or even the wall that modern architecture is supposed to have eliminated completely, the wall is in no way a stable and unequivocal idea—and still less a simple structure that imposes its norms on the total system. Rather, it is the system itself that assigns the wall its place in the hierarchy of constitutive elements, thus endowing it with its logical value, constructing it, and setting it up where appropriate as a generative structure. In accordance with the classical order (from which the column cannot strictly speaking be deduced), the wall appears as the support for a certain number of functions, essential or discretionary, from which the systems are selected: one system stressing the load-bearing function of the wall, another its function as a screen, another the outer skin, and yet another (as we will see with Alberti) its inner articulations.

The wall, then, is not an objective idea. In fact, a wall is only a wall when it isinstituted as such, and this institution acquires a logical and structural value depending on whether the structure operates as a generative, or merely subordinate, element of a system. That is to say, a rational inquiry into the wall cannot proceed on the assumption that it is a natural and unequivocal reality, for the oppositional, if not contradictory, relationships are inherent in the structure as such, even when the architect claims to celebrate the unity and coherence of the partitioning (paries). This is particularly evident in the case of Renaissance architecture (which we can indeed define as wall architecture), but only if the structure in question is understood as the site of an articulation that, even if it occasionally takes a conflictual turn, is no less essential or irreducible. This is why the architects of Alberti’s generation, who considered the niches and engaged columns of Brunelleschi’s Santo Spirito to contradict the principle of the continuous wall, developed in their turn a simulacrum of the wall and established in the same gesture the wall (though a contested one, a wall called into question as such) as a fundamental structure of the new architecture—as if its affirmation only had meaning in this instance with regard to its possible negation. This is the contradiction that will haunt architecture throughout the so-called mannerist period and into the age known as the baroque. Architects would strive to overcome it by superimposing a grid over the surface—or at least the elements of a false articulated framework—a combination of the classical order and the wall (and no longer just their simple opposition). In this way, the classical system, which is the basis of both mannerist and baroque experiments, was endowed with a paradoxical dimension oftruth—albeit a truth corresponding to the fundamental intention of the system. It was Goethe who observed that despite the contradiction involved with combining columns with walls, there was something “divine” in Palladio’s plans, “something comparable to the power of a great poet who, out of truth and falsehood, creates a third term whose borrowed existence enchants us.”18 Yet here one should guard against using Palladio’s example to draw an overly strict division between reality and appearance, truth and lying. No longer conceived in terms of the Roman system, Goethe’s “third term” in no way depends on the category of the mask; for if a mask exists, the column order and the wall can each in turn function as a mask, as a false structure overlaid on the real.

The fact remains that if the wall is seen as an institution, it is not only as a three-dimensional structure with the potential, when appropriately treated, to be used in various contexts. Even where the wall cannot be reduced to a simple simulacrum (the most frequent case), it appears as the result of a constructional operation and of an already institutionalized technique, which in turn entails a series of structural consequences that have an effect on the system as a whole. This is why, when dealing with the logic of the wall and with the problem of wall architecture, we cannot simply dismiss in a few lines Alberti’s long exposition of technical developments in building and the elements composing theparies, that ever-privileged structure to which he devotes the first three books of his treatise. Alberti even goes so far as to use the two termsstructura andparies interchangeably to designate the same reality, one that is in no way reducible to the “wall” (mur) in the strict sense of the term. Of the three components of the art of building that constitute the material edifice—the wall, the roof, and the openings—theparies comprise every vertical structure supporting a covering (in the same way that thetectum designates not only the roof but also any type of “covering,” whether floor, ceiling, vault, etc.).19 To translatestructura and evenparies as “wall” (mur) in fact prevents us from following Alberti’s reasoning to the end and from measuring the scope of a reflection aimed at nothing less than inscribing in the wall itself the structural determinations obeyed by a system that is based, from Brunelleschi’s day, on a double movement of assertion and negation of the wall (paroi), seen in its continuity and its regularity.20

To ask whether Alberti, given the position of the wall in his problematic, was more Roman than Greek is to forget that this first great Renaissance theorist was above all a man of his times and thus keen to interrogate the past and interpret its remains, but within the terms of a culture that was not without its ties to the trecento nor solely committed to dealing with the ancients and the reestablishment of the civilization of antiquity21—a culture completely bound up, in its humanist project, with a mental apparatus and a set of professional traditions that surface most clearly (and with good reason) in the technical domain. Is architectural practice, then, as Alberti defines it, the reflection of Roman modes of construction? Does it thus owe nothing to the legacy of the Middle Ages? The question is posed on the very ground that served as a base for Alberti’s own thinking, as he showed himself (at least initially) to be more concerned withconstruction than withform giving.22 After all, it was not only a wish to distinguish himself from Vitruvius that compelled Alberti to give his treatise a title in which construction explicitly prevails over architectural aims. InDe re aedificatoria, problems of a mechanical and technical nature are no less important than considerations of harmony and number, fashion and ordering (considerations often overemphasized by academic criticism). Nothing in Alberti’s analyses, apart from a few debatable references, allows us either to link his concept of the wall to the traditions of Roman masonry or, less still, to oppose the principle of the solid, homogenous wall to the Gothic (or even contemporary) model of a load-bearing skeleton that may be completed with a simple infill.23 It remains for us to inquire how, following the example ofDe re aedificatoria, the difference between two types of architecture—one according the wall a primary place among the elements of the art of building, the other relegating it to a subordinate position—operates not on the level of constructional necessities but in terms of their interpretation according to the perspectives of the Albertian system.

It is a mistake, writes Alberti in Book Seven (which is devoted to the “ornamentation of sacred buildings”), to believe that the thickness of the wall adds to the majesty of a temple. Is not Hadrian’s Pantheon made up of asolid skeleton into which intervals are hollowed out with niches and openings—thus considerably reducing load and cost while the building gained in elegance?24 Whatever attitude toward the monuments of antiquity is revealed by this interpretation (the Pantheon is one of the rare Roman examples referenced inDe re aedificatoria), we see that when Alberti defines theparies as structure he is not thinking solely of masonry (unlike Vitruvius) any more than he sees the wall as a homogenous and continuous mass. And if he distinguishes between the different kinds ofstructure, in the Vitruvian sense of the term, then this is done to comprise the three modes of facing stone—ordinary (ordinaria), reticulated (rheticulata), and “uncertain” (incerta), or as Jean Martin translates it,rustique, made up of unhewn stones—which in turn correspond to the three parts of the wall: the base (podium), the middle (procinctus), and the upper (corona).25 To this initial distinction between the successive (or should we say superimposed?) parts of the outer walling should be added the differentiation between the inner infill (media muro infarcinatio) and the outer revetment (cortex)—that is, between the inner cement and the outer skin, or “crust”—which vary depending on the type of wall under consideration.26 But the distinction between the vertical and horizontal layers making up theparies does not exhaust its structural features. The parts of the wall that belong to the skeleton must also be defined: the corners and buttresses; the pillars, or “columns,” inserted in the wall (which function like bones supporting the covering);27 and the infill parts between the bearing elements.28 Are we then to suppose that the prevalence, at the time Alberti was writing his treatise, of the “bony model” of structure, which he conceives as the solid armature of the building, proves that he was still in the grip of the Gothic building tradition or that, on the contrary, the subsequent progressive elimination of the column from his built work illustrates a shift toward a wall architecture, rigorously conceived and deduced?

There is nothing to indicate that Alberti, in the moment of writing his theory, hoped to save on the cost of the wall by preferring a discontinuous skeleton. Rather, his entire effort seems to have been directed toward defining a mode of construction in which the skeleton could not be distinguished from theparies and in which the relationship between the column and the wall was expressed in mechanical (rather than decorative or plastic) terms. In such a system, the column could not be opposed to the wall any more than it could be simply coupled to it. The column constituted the system’s principal element, and the wall was raised in proportion to it—no higher, wider, or thicker than the rule (ratio) or the mode (modus) required.29 In articulating the wall in this way, Alberti resolved both technical and economic problems by conceiving of a structural arrangement that assured the stability of both the walls and the “covering, or roof.” Anyone who took no heed of expense might just as well build the whole building as a “continuous column.”30 But that would be both wasteful and incongruous. A masonry skeleton infilled with smaller mortar-bound fragments—whose division, Alberti notes, parallels that of the social body—would guarantee stability.31 When theparies is defined as a structure that supports a roof, the concept becomes much broader in scope than a wall (mur) in the strict sense of the term. Once again, if Alberti is to be believed, the order is nothing but a wall pierced in several places by openings.32

In such a system, the column does indeed appear to be areinforced part of the wall. As if recognizing the paradox involved in such an assertion, Alberti insists that “it may not be wrong to describe [the column] as a certain, solid, and continuous section of wall, which has been raised perpendicularly from the ground, up high, for the purpose of bearing the roof,”33 given that the disposition of columns and the spaces between them is related to the load. As for the openings and passages let into the wall, Alberti further notes that the ancients were careful to pierce only the weakest sections of a wall that had little or no load-bearing function, and then as far as possible from the corners and the points where columns rose, while keeping great sections of the wallcomplete and unbroken.34 In fact, it seems that Alberti intended to take a critical attitude toward the ancient models, recognizing the value of a mode of construction that, unlike the Roman system, allows for a greater number of openings—by which he meant not only doors, porticos, and windows, but also niches and recesses that,without piercing the whole thickness of the wall, add to its elegance and lightness.35 This is to say nothing of the fact that an opening, far from being detrimental to the stability and strength of the wall, may indeed contribute to it, provided it is treated in accordance with Alberti’s principle, with the jambs taking on “the character of columns”36 that, covered by a lintel in the form of an architrave or arch, are themselves counted among the bones of the skeleton: “For I call an arch nothing but a curved beam, and what is a beam but a column laid crossways?”37

In this way, step by step, the building as a whole is conceived as skeleton and infill. All that has just been said about the wall is equally valid, mutatis mutandis, for the coverings; the beams, in turn, are nothing but columns laid transversally and the arches themselves but bent beams.38 Better still, where the roof spans a vast surface it should be articulated and compartmented following the same principles as the wall.39 Alberti, to repeat, did not appreciate bare surfaces without relief: if a wall is too long, columns should be used to ornament the wall over its full height and should be spaced far enough apart to let the eye rest and to make the length of the wall appear less offensive;40 if it is too thin, either a new section should be added to the old to make a single wall, or, “to save expense,” it could be reinforced by means of “bones” (i.e., pilasters or columns).41 Should a wall be too high, a second story of columns (or preferably pilasters) may be added with little expense, on top of the ground-floor columns, to guarantee the firmness of the wall and to imbue it with an incomparable majesty42—horizontal and vertical partitioning simultaneously satisfying both the requirements of stability and the imperative of “dignity.”

There is no formalism in this. What Alberti was defining, in theory, was neither more nor less than a structural model that, by submitting the classical orders to the law of theparies, made explicit their constructional function. This was in essence the system of architecture Viollet-le-Duc would praise Philibert de l’Orme for having defended in an age when, as he claimed, architects professed the greatest scorn for masonry and were only interested in “marvels” (mirelifiques)—ornaments without rhyme or reason.43 But did he not think that even in Italy, the architecture of Bramante and Palladio had itself responded to this trend, which in no way excluded—no more at the Vatican or in Vicenza than in the Tuileries—a spectacular handling of the orders? Certainly, the pilasters of Valmarana Palace, built of bricks like the wall itself, are no less dependent on the wall than were the ringed columns of de l’Orme’s Tuileries facade, of which Viollet-le-Duc approved for its correspondence with projections in the wall’s foundations. What would he have said about the arcades in the courtyard of Saint Damasus inside the Vatican, where Bramante demonstrated the principle of superimposed orders and their potential for developing walls that were extremely light and virtually transparent?

Long before Choisy and today’s engineers, Alberti recognized that despite its monolithic appearance the wall of Hadrian’s Pantheon was itself reinforced by means of a network of superimposed brick arches embedded in the mass of the masonry, with the wall presenting itself as arational system in which the loads were progressively distributed and concentrated on eight enormous pylons corresponding to the nonvoided parts, as revealed by the floor plan. Yet there is a big difference between this model and Alberti’s interpretation, from which he draws conclusions as to the constructive use of the classical orders. For the Albertian skeleton is not necessarily, or even principally, made up of solid elements embedded in masonry. In fact it consists of areinforcement of the wall, a reinforcement that can be external to it so that the applied order contributes to the stability of the whole while also fulfilling its own specific function, which is to support the bony rib elements of the roof. For whoever wishesto build at little expense (a constant concern for Alberti’s contemporaries, as for those of de l’Orme and Jean Martin), such a dressing of the wall provides a particularly refined principle of construction, so long as care is taken to link the external orders to the internal ones by long stone ribs running crossways through the entire thickness of theparies.44 Thus, by a structural inversion for which we are now prepared (and whose modernity we do not need to stress), this would ideally ensure the cohesion of the double network of bones into which the wall is set.

As the most solid part of the wall, the column, “and all that relates to it,” is indeed “the noblest” of the wall’s elements, in both its form and its functions, and even in its very display.45 Nevertheless, if the column, in the strict sense of a standing shaft, can be regarded metonymically as representative of a much more general class—indeed, Alberti did not hesitate to assimilate pilasters with square columns (columnae quadrangulae), beams and inferior purlins with recumbent columns, and even arches with curved columns, and so on—this is at the cost of an ambiguity that he did not care to resolve. As a fragment of the wall, and a structure’s noblest element, the column nonetheless possesses an identity, if not an autonomy, that is particularly marked in the case of monolithic columns hewn from a single block. As remarkable for its technical quality as for the beauty of its proportions, the column also appears metaphorically as the model par excellence of the bone of the skeleton: a discrete structural element, itself articulated (if considered as a whole with its base and its capital) and suited as such to being combined with other elements of a similar nature so as to constitute the solid framework of a building. When Alberti defines the column as the principal ornament of architecture, does he mean to ignore its structural properties in order to concentrate solely on its appearance, its decorative value? In fact, it does not seem as though he saw the relationship between structure and decoration in terms of an entrenched opposition. Books Seven, Eight, and Nine of his treatise, although dedicated to the ornaments of sacred buildings and public or private constructions, deal in detail not only with the decoration of those buildings but also with their general arrangements, plans, main parts, and the different elements in use. The fact is that any single structure is likely to contribute to the ornament of the whole: the column to that of the temple, the temple to that of the city, and the city to that of the state. A building has no finer ornament than its columns. But what would a town be if it were stripped of its buildings, and even of its inhabitants, who by their number ultimately represent its finest ornament and (we would have to agree) its most essential?46

Brunelleschi placed the Florentine Renaissance under the sign of the column as much as of the cupola. The paradox of the “austere” style generally associated with the Counter-Reformation—(which could claim Alberti among the initiators a century before the promulgation of the edicts of the Council of Trent)—is that it tended to economize on this incomparable ornament—if not eliminating the column completely from architecture, then at least restricting its use to functions and strictly defined parts of a building that often had more to do with furniture (altars, etc.) than with masonry. As we have seen, a similar concern for economy was present in the writings of Alberti, who seems always torn between his desire to see architecture held to a tasteful modesty and his idea of the representative value that attaches to its works, particularly to sacred buildings. The systematic and rationalizing effort ofDe re aedificatoria is thereby all the more significant: educated as he was in the linguistic disciplines, Alberti conceived of a logical procedure that would govern any handling of forms in accordance with theirdefinition,47 a definition that each generation was obliged to formulate for itself. Indeed, in the case of the column, the structuralist approach of the present essay parallels the concern that motivated Alberti to justify the use of this architectonic member from a standpoint that was not merely archeological, or picturesque, to use the strict sense of the term, since, as Alberti states inDella pittura, architecture borrowed its ornaments—starting with the column—from painting.48 Yet the reciprocal is also true: it was obviously not for strictly logical reasons that the column, so brilliantly celebrated by Brunelleschi, was eliminated from the architectural vocabulary of the following generation, only to return with familiar connotations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Alberti’s rejection of the column as the principal element of architecture in his own architectural practice does not imply that, as an architect, he broke with the concepts he defended as a theorist, including in particular the definition of the wall that we find inDe re aedificatoria. Alberti admired certain old masters for knowing how to erect vaults in such a way that the columns could be removed without compromising the stability of the structure as a whole. If such artifice amazed him, however, it was not because he regarded the column as merely a decorative element; the presence of a regular row of flat pilasters over the facade of the Palazzo Rucellai (where those pilasters combine with cornices to form a veritable tracery thrown like a net over a wall treated with flat rustication), as well as over the facades of Sant’Andrea and San Sebastiano,49indicates that he never abandoned the principle of the articulated wall. It matters little in the end whether or not the order has a constructional value, for even if the column may be eliminatedas a form, the articulation of the wall following the lines of a skeleton is maintained.

So it was in no way the so-called logic of the wall that led to the exclusion of the column, but the very opposite. The elimination of that eminently plastic element seems to have allowed Alberti to consider the wall as a support for words (orders, triumphal arches, etc.) that could be inscribed in ways that would no longer be structural but spring instead from a very different order of determinations: that of the graphic, of the drawing, known otherwise as “drawn architecture” (l’architecture dessinée) that would become the support of academic instruction.

3.1

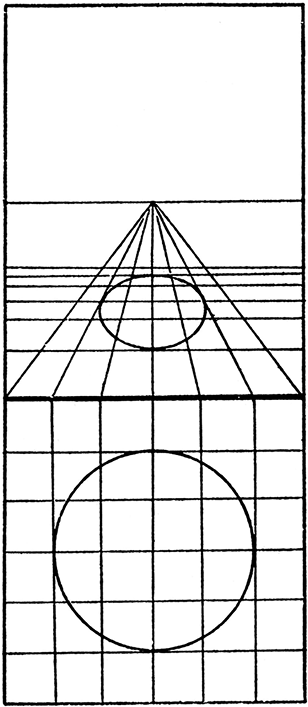

Diagram of a circle drawn in perspective. From John Spencer, “Notes to Book Two” (1435), inOn Painting, by Leon Battista Alberti (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1956).