4 Perrault’s Colonnade and the Functions of the Classical Order

On May 14, 1667, Jean-Baptiste Colbert presented Louis XIV with two drawings for the east facade of the Palais du Louvre, after Louis Le Vau, Charles Le Brun, and Claude Perrault—the members of the committee charged with finalizing the project—had been unable to agree on a singleparti. Of the two drawings submitted to him, the king would retain the first, the one “adorned with an order of columns forming a peristyle or gallery above the first floor,” over the other, which according to Perrault was “simpler and more unified, without an order of columns.”1

I do not wish to intervene here in a discussion of the problems of attribution posed by the Louvre Colonnade. I am content to introduce a few thoughts that seem to me to clarify its significance and to briefly demonstrate that the choice offered to Louis XIV was neither gratuitous nor arbitrary and that his decision would not have been simply a matter of taste. If the selection may appear to illustrate the king’s penchant for pomp, grandeur, and a certain form of ostentation, it corresponds more profoundly, as we see in its antecedents and implications, to a form of logic that since the mid-sixteenth century never ceased to play a determining role in the historical development of the Louvre and in the avatars of what has been called thegrand dessein.

4.1

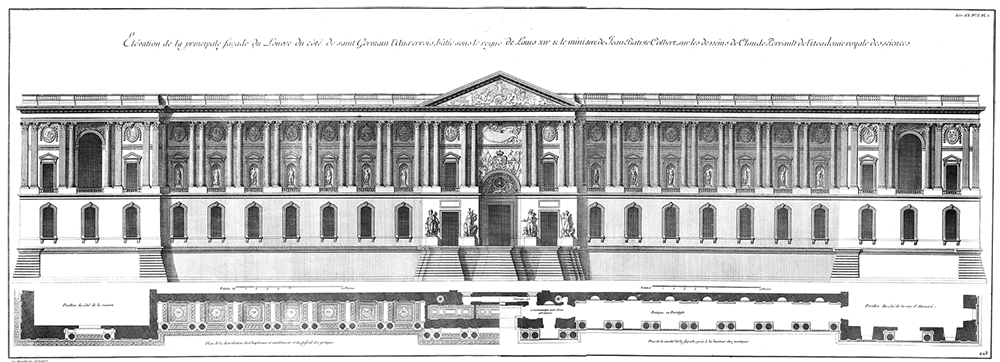

Engraving of the east facade of the Louvre. From Jean Mariette,L’architecture Françoise (Paris, 1738). Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

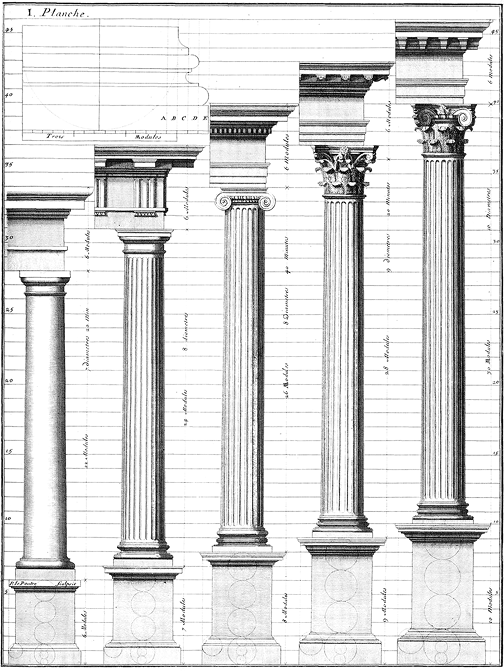

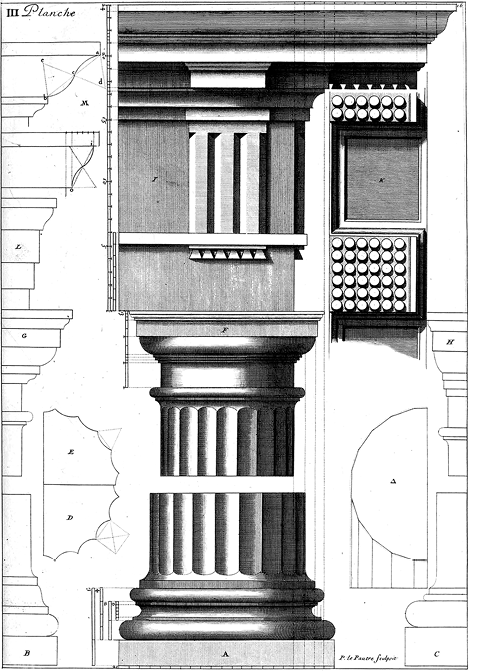

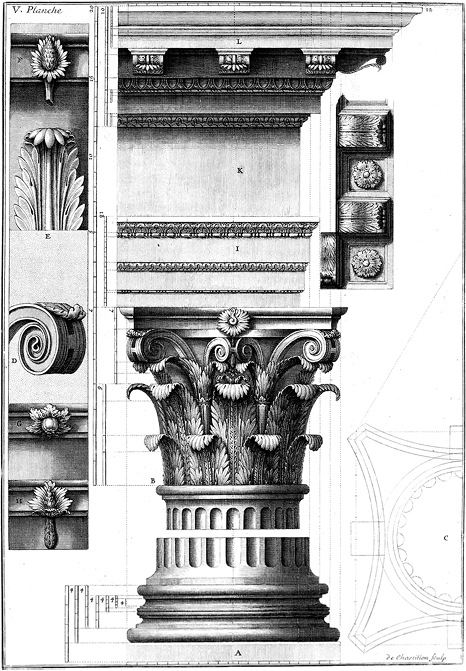

If we claim to be able to determine what the significance of the colonnade might have been over the course of the classical age, then we must accept a priori (and without this being a simple tautology) that a building such as the Louvre had to be organized in a way that could, as a whole and in its parts,signify something. We thus need to define what the building constituted as an ordered whole as well as what classical architecture itself was as asignifying order. We know that, as Michel Foucault brilliantly reminded us, the notion oforder, associated with that ofmeasure, occupied a central place in classical thought.2 And it is not merely playing with words to insist that the architecture of the century of Descartes and Leibniz was itself based not only on knowledge and the institution of the principles of the classical Order (with a capitalO)—understood, following Perrault’s definition, as furnishing a rule for the correct proportioning of columns and their ornaments and for figuring the elements appropriate to them3—but also on a much more general notion of order defined by Vicenzo Scamozzi, in extremely vague terms, as “a certain kind of excellence that greatly increases the good grace and beauty of edifices sacred and profane.”4 Other authors such as Roland Fréart de Chambray assimilated the idea of order toordonnance, by which they meant bothordinatio anddispositio in the sense those two terms have in Vitruvius—namely,ordinatio meaning that which determines the relative size of the different parts that compose a building anddisposition (or as Perrault also calls it,distribution) meaning that which determines the placement, sequence, and connection of those same parts according to their characteristics.5 Thus, when speaking of order, we should beware of an ambiguity that in the eyes of a disciple of classicism could mean the order of a facade, a building, or even an urban ensemble, without any application of the classical orders. Yet from the moment that the elements (in the archeological sense of the term) make their appearance, a certain number of observations emerge that give rise to the thought that the implementation of elements did not simply obey considerations of measure and harmony but also responded to a strictly formal order based on a network of structural relationships, the most visible of which are topological in nature. (This occurs even if we confine ourselves to considering the way these elements are used, how they are divided up over a facade, and especially their relative distribution,according to their characteristics, across the different facades and parts of the same building.) In this context, I want to demonstrate (all too briefly and with the single example of the Louvre Colonnade) that the distribution of the elements of the classical order across the different parts of the building demonstrates the existence of a veritable topology of the classical order, one which has never been given explicit form in theory but which must nonetheless be considered as one of the formal components that constitute the classical system as a signifying system.

An initial formal sequence that can be to put into play in terms of opposition, distribution, correlation, and substitution is formed by the sequence of the three external facades of the Cour Carrée: the north facade, on the rue de Rivoli, which is devoid of all decoration and simply pierced with windows and which Perrault apparently completed according to Lemercier’s original scheme; the east facade, which corresponds to the colonnade; and lastly the south facade, which in its current state presents a colossal order of pilasters extending over two stories of windows, supporting an entablature and a balustrade, and resting on the same high base that serves as the base for the colonnade. These three facades are well known to every passerby. The important thing is to see that they form a system and that, beyond the order of rules referenced by the members of the academy when discussing the projects submitted to them, what emerges is a form of structural regulation, the effect of which seems to have been experienced over the course of execution and which tended to establish a systematic and coherent play of oppositions between the principle of the bare wall, that of a colossal order of pilasters, and that of an open colonnade in the form of a peristyle or gallery.

4.2

Claude Perrault,Ordonnance des cinq espèces de colonnes selon la méthode des anciens (Paris, 1683), plate 1. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

As a number of historians attest, when work on the lengthening of the colonnade caused the south facade to be set back fifteen meters from the corner of the east facade, Perrault was led to bring it back into alignment. Yet the same demand for regularity, in keeping with the canons of classical taste, would have no effect when it came to the north facade, whose nonalignment was not corrected. If, as a working hypothesis, we ignore the functional demands that could lead to the doubling of the south wing and the correlative widening of the colonnade’s corner pavilions (namely, Colbert’s decision to shift the king’s apartments, originally planned for the east wing, to the wing with a view of the Seine6), then we see that, from a strictly formal point of view, the scheme for the facade set up by Perrault in front of the one built by Le Vau from 1660 to 1663 came down to the substitution of a facade composed of two main buildings pierced simply by windows, without any other decoration, and joined together by a central pavilion with a colossal order of columns—a type of facade that was far more regular and imposing and in which the pilaster reigns undividedly. Even if Perrault meant to embellish the central part of this same south facade with columns, as the plan published by Blondel indicates,7 the fact that such a plan was not pursued underlines the constraining power of the formal order that causes the three facades to constitute a ternary play of opposition (bare wall to open colonnade to colossal order of pilasters) wherein each facade assumes a differential value.

In addition to this primary register of opposition, there is a second, subtler, perhaps more significant one that escapes immediate observation: the relationship between the internal and external facades and foremost between the open column opposite Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois and the facade on the courtyard to its rear. It would be interesting, from this point of view, to study the series of plans, both French and Italian, that were proposed for finishing the eastern part of the Louvre. Most of these turned on a simple opposition either to emphasize or to overcome, if not to conceal, this part of the building. Thus, in 1661, Antoine-Léonor Houdin proposed to put up an east facade comprising a gallery with a colonnade detached from the wall, leaving the inner facade to be finished, it seems, following Lemercier’s scheme for the internal north facade. Conversely, Le Vau’s plan of 1663 suggests placing an open gallery with a colonnade into the courtyard at the rear of the east wing, while the external facade was to be embellished with an order of engaged columns. Bernini, in his first project of June 1664, established a double-story portico around the entire perimeter of the courtyard and joined together on the outside the corner pavilions of the north and south wings by a curvilinear facade decorated with a colossal order of columns over two stories high and pierced by loggias—the opposition between the internal and external facades here overcome with the building opened up as much inward as outward. Whether or not they planned to endow the internal courtyard with galleries or porticos, most of the architects concurred in the adornment of the external facade, which in principle faced the city, with an order of columns or even a colonnade forming a peristyle or gallery (to use Perrault’s terms). This consensus seems to correspond, on a formal level, to a profound mutation of, if not a rupture with, the principles defined by Pierre Lescot—principles to which, up until Colbert was appointed superintendent of buildings, the Louvre architects seemed inclined to show themselves faithful.

Lescot’s Louvre in fact corresponded to a simple given: the elements of the order, whether columns or pilasters, were reserved for the internal facades on the courtyard, whereas the external facades were only pierced with windows, the wall being left bare. But if the orders do not appear, not even simply set into the wall, on the external facades—neither the one facing the Seine nor the one facing the densely populated neighborhood that had sprung up between the Louvre and the Tuileries—this is perhaps because the use of the components of the order, and particularly of the column that constitutes its main element, corresponds in principle to the aim of opening up and communicating with the outside world, an aim manifest in the case of a portico or of loggias but blind, or at least more discreet, in the case of orders set in the wall. In Lescot’s initial project, thecorps de logis with which we are familiar (and which now corresponds to the south half of the west wing of the Cour Carrée) was to be framed on two sides by porticos lower than the facade itself, with the courtyard opening to the outside world, following the classical scheme adopted by Serlio for Cardinal de Ferrare’s Hôtel at Fontainebleau. Lescot’s use of the elements of the order responded to a given that was ambiguous yet typically French, in that the internal facade was intended to be partly visible from the outside. This ambiguity would be removed by the option of a quadrangular palace with corner pavilions and four identical main buildings opening onto an internal courtyard, which (compared to the initial plan) shows an evident desire for retreat and isolation, if not for defense, with regard to the urban setting.

A portion of the gallery overlooking the water was to have been ornamented at the end of the sixteenth century with a colossal order of pilasters, whereas Philibert de l’Orme’s Tuileries responded to yet another given—that of a loggia with columns opening onto the gardens and, we should note, decorated with pilasters at the back, as though the architect had intended even here to set up an opposition that of course has its logic. If we bear this in mind while considering in the abstract the play of oppositions between the different facades and the parts of the complex then formed by the Louvre and the Tuileries, then those oppositions seem to be organized according to a formal model that is certainly incoherent, sloppy, and badly articulated. But this model is in fact not far from a model that is affirmed, in far more rigorous and systematic guises, in various Italian palaces, whether the Farnese Palace in Rome or the Palazzo Te in Mantua: external facades devoid of all decoration (or embellished with only slightly projecting pilasters), internal facades decorated with columns engaged in the wall or forming a peristyle, and facades with loggias or galleries that open onto a walled garden cut off from the urban environment.

We might feel that the project for a uniform east facade devoid of any order of columns—the one Louis XIV set aside—better satisfied the rules of a topological distribution of the elements of the classical order, which we have just defined. But opening a peristyle (or a colonnaded gallery) onto what was supposed to be the palace’s external facade would have marked a decisive break with that formal model. Thus, the alternative proposal left the king with a decision that in retrospect appears to have been a matter of government, if not of state. Yet are we really to think that putting up an order of columns detached from the wall along this same facade (with the side pavilions, which projected slightly, decorated according to a similarly logical transformation—not with the customary columns but with pilasters) would have ended the slow process that was to transform the Louvre castle (not to say fortress), set as it was both on the city wall and on the river (as Alberti recommends, for reasons of security), into a palace largely open to the city? This would be to forget that, as Alberti would say, if every tyrant is partially a prince, every prince is himself partially a tyrant; thus, every castle should be partially a palace, and every palace partially a castle.8 The fortress of the prince should not resemble a prison, but neither should his palace be open to all winds and in no state to withstand the onslaught of the crowd, which Alberti, quoting Euripides, claims is always full of evil intentions.9 Memories of the Fronde had not yet been erased in the period when they were arguing over the completion of the king’sgrand dessein, as evidenced by Colbert’s objections to Bernini’s projects: with the royal apartments located in the east wing, the sovereign would have been less protected against a seditious movement, since the open loggias and the columns generously distributed throughout the galleries and vestibules would have provided numerous points of access and hiding places for those plotting a coup.10 We cannot be sure that in selecting the plan for the facade with the peristyle or gallery the sovereign wished to disregard such concerns any more than he would have broken with a formal apparatus of which the colonnade, in principle, represented not so much a negation as a reversal.

We might recall that as early as 1668 Colbert envisaged transferring the king’s apartments to the south wing of the palace, overlooking the Seine. But the very termperistyle—which Perrault, as a translator of Vitruvius, used to designate the colonnade—gives pause for thought. What did this word mean for him? In a note in his edition of theTen Books on Architecture, Perrault spells it out very clearly: the essence of peristyles is that they have columns inside and walls outside—not columns outside and walls inside, as seen in monopteral and peripteral temples and in porticos at the rear of theaters.11 This means that the project retained by the king, which comprised an order of columns forming either a peristyleor a gallery, was perhaps itself an alternative proposition: either the facade actually opened to the city and could then be described as a “peristyle,” with the columns outside and the wall inside, or, as in Lescot’s earlier project, it faced a courtyard, with the columns inside and the wall outside. Here, we should remember that the initial idea for a colonnade, in Léonor Houdin’s project, specifically allowed for a closed place in front of this same colonnade—or, to put it more clearly, a kind of courtyard that would have been bordered to the north and south by porticos connecting the palace to another circularplace, also closed, on the Châtelet site. We might further recall that projects for creating a monumentalplace in front of the colonnade and its facing buildings proliferated throughout the entire eighteenth century, right up to the nineteenth, as if in an effort toclose up the opening inscribed in the very ordering of the Louvre’s east facade—to blind, contradict, or negate it by opposing it with another, complementary facade of identical ordering.12

4.3

Claude Perrault,Ordonnance des cinq espèce de colonnes selon la méthode des anciens (Paris, 1683), plate 3. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

4.4

Claude Perrault,Ordonnance des cinq espèce de colonnes selon la méthode des anciens (Paris, 1683), plate 6. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

Thus, it seems as if, over more than two centuries, thegrand desseins of kings had undergone a gradual expansion simply because the plan to open the palace up to the city, though intensely desired, was endlessly deferred, postponed, and ultimately rejected. Through a sort of deliberate misinterpretation (accentuated by the 1964 excavation—certainly spectacular, but at the very least questionable—of the moat at the foot of the colonnade), the colonnade took on the characteristic of a paradoxically decorative element, which may not have been present in the minds of its creators—Perrault in particular. This is due first to the colonnade’s position (it faces the city without any transition) and second to the digging of the moat, which restored its fortified aspect. It would thus be an error to consider and analyze this facade separately from its context; the contradiction (or at least the paradox) it implies owes less to Perrault than to the program imposed on him, or even to the king himself. Just as thegrand dessein was at the point of achieving its definitive form and logical conclusion—and of the Louvre being transformed from a castle to a real palace open to the city—Louis XIV effectively turned his back on Paris, first by taking up residence in the wing overlooking the Seine and then by moving to Versailles. Indeed, during construction Perrault decided to seal up the open windows behind the colonnade and replace them with niches for statues,13 as though he intended to signify that opening the palace up to the city could only be a sham or feint. The formidable deployment of columns in front of the blind wall hence confers a provocative value on the facade and at the same time amounts to an admission of failure to which we are no longer sensitive today.

At the beginning of this chapter, I declined to enter into disputes over attribution. But considering what I have said as to the way in which formal determinism would have weighed on the entire historical development of the Louvre, as well as the rhetorical character of the work of those architects attempting to elevate the classical order into a signifying system, it seems that we should see Perrault (who, like Lescot before him, was not a professional builder but a scholar and thinker of language—andfine language at that) not as the inventor of the Louvre Colonnade but as one who was able to conceive of its most coherent and expressive idea. It is nonetheless true that after having closed the rear wall of the colonnade Perrault soon after envisaged opening a suite of galleries onto the courtyard,14 which reveals the extent to which this great thinker would have been aware of the logical implication of his architecturalparti and of the problems posed by the opening up of the prince’s palace, both for itself and for the outside world. With Claude Perrault, the clearest concept of the order and its functions is affirmed for the first time, no longer picturesque or symbolic, but systematic and appropriately significant.

The foregoing analysis is admittedly not without its relationships to that type of contemporary description in the study of systems—more precisely, signifying systems—with respect to which architecture presents itself as a particularly complex and interesting model. This is why, in conclusion, I would like to cite from the preface written by Perrault to introduce his translation of Vitruvius, in which he makes reference to language, to writing, and even to clothing. This text seems to me in effect to justify my proposition here, as well as those of the classical architects, concerning the way one can superimpose on the order of utilitarian functions (to which the built work must respond) another order, one that is arbitrary and conventional—a procedure that, like any code, language, or system of signs, will be imposedby institution and, as such, will have authority: “It is certain that rules are so essential in all things that, if Nature refuses them to some things—as she has done with language, with the letters involved in writing, with clothing, and with all that depends on chance, will, and habituation—the institution of man must furnish them, and for this we agree upon a certain authority that takes the place of positive reason.”15

5.1

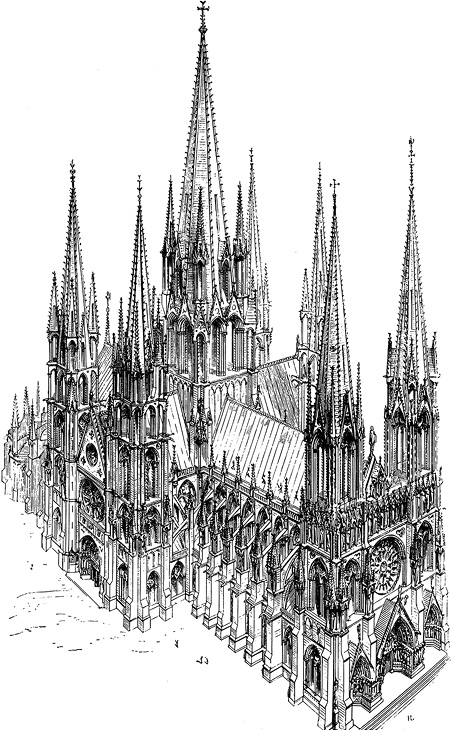

The ideal cathedral. From Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, “Cathedrale,” inDictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1854–1868), 2:324. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.