6 From Structuralism Back to Functionalism

“COLUMN: n. A stone cylinder placed on a base or a pedestal, supporting an architrave or an arch.”1 Viollet-le-Duc’s definition of a column in hisDictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVe siècle calls for a certain number of remarks, the pertinence of which will not necessarily be limited to French architecture from the eleventh to the sixteenth century. As far as archeology goes, the column actually counts among those members of architecture whose seeming universality calls out for its nature both in space and in time to be questioned. This is to say nothing of the fetishism evidenced by its recurrence at certain moments in the Western tradition, in more or less time-honored though occasionally aberrant forms—the same fetishism exhibited in its most direct form in the Middle Ages, in the practice of thereuse of antique columns sometimes transported over considerable distances.

Viollet-le-Duc’s concise definition has the merit of clearly stating the facts of the issue posed in structural terms. At the outset, however, he emphasizes the potential ambiguity of the subject: a column is indeed a stone cylinder, but it is not only that. This cylinder takes on a value and a figure as a “column” only once it is linked with two other members of architecture: thebase on which it rests and thecapital with which it is crowned. As for theshaft, theDictionnaire defines it as “the part of the column included between the base and the capital.”2 In other words, the column was established at the outset as a complete and articulated form, deriving from the joining of several differentiated and complementary elements, and should thus be considered in its relationship with other members of architecture—in this instance, the lintel and the arch.

Seen in this way, the definition of the column may be understood as characteristic of the guiding intention of theDictionnaire and of the constant transition from observation to explanation, description to argument, and history to theory that makes for its originality. As its title suggests, theDictionnaire is indeedraisonné, and in the most deliberate and insistent fashion. Considering each element, each member, of architecture one by one in its concrete historical evolution as revealed by archeology, Viollet-le-Duc focuses on uncovering their raisons d’être, demonstrating thewhy behind each and bringing to light the logic that might regulate its use and govern its morphological and functional evolution. And it is exactly so with the column, which should not be seen simply as a conventional form deriving from the conjunction of aleatory, or merely decorative, elements. This member of architecture has a determined use value.

The sequencebase, shaft, capital does not, however, have a raison d’être in itself. To understand the succession, connection, and combination of these three terms within a unitary form, we must refer to the function of the vertical fulcrum that has devolved to the column in the structural system. Viollet-le-Duc’s definition of the column accomplishes this while also making perfect sense of what we might call the hierarchical arrangement of that which functions as a completely separate structural element. In the end, a column can be reduced to a skittle stood perpendicularly to the ground in order to support a vertical load. This implies that the shaft constitutes the centerpiece, whereas the base and capital play only secondary roles. The footing marks the passage, or transition, between the vertical axis of the support and the horizontal foundation of the edifice (an apparently unnecessary function, judged by the Doric order). The capital itself emerges as the obligatory complement to the shaft, whether the projection of the capital reduces the span of the lintel and thus prevents the rupture of the horizontal block supported by the column or its flared form provides a cantilevered equilibrium, ensuring the seating of a lintel that is wider than the shaft’s diameter or of the springing of an arch whose section at the level of springing is greater than the section of the load-bearing cylinder below it.

Taking into account the function it fulfils in the context of any given building system and the fact that such a system obeys either the principle of the lintel or that of the arch, we must accept that the form derived from joining a shaft, a base, and a capital is in no way arbitrary or conventional. Rather, this joining presents itself as a structural unit whose constitutive elements demand to be viewed in their functional articulation, with each part presenting a perfect “solidity”both in appearance and in reality.3 This role of balancing appearance and reality, being and seeming, in the genesis of the ideology of modernity scarcely needs to be recalled. But the subordination of the various elements of the column and their component parts toreason, to thewhy that governs their organization as a form, is again illustrated by the fact that certain parts do not rightly belong to any particular element, and their function as a “hinge” never appears more clearly than when it gives rise to a shift in articulation. Consider, for example, theastragal, the molding that separates the capital from the shaft. It could be part of the shaft, as in Romanesque architecture, wherever the shaft bulges or tapers, or it could be part of the capital, as when, for reasons of economy, the shaft takes the form of a perfect cylinder, as was the case with Gothic architecture from the thirteenth century on.4

The same is true of theabacus, which after long constituting an independent slab designed to support the springers of an arch was over time absorbed into the same course as the capital before disappearing as an identifiable element when the capital was reduced to a simple ring at the junction of the arch and the pier.5 The constitutive elements of the column are to a certain extent optional and interchangeable; their number is not a fixed imperative, and their enumeration alone does not define the column as such. Yet the characteristic articulation of the parts within a unitary sequence and in keeping with their function seems to be the fundamental rule of the column. Thus, strictly speaking, the column should be defined first as astructure, then as aform, in that the concept of structure implies the idea of organization or design, not a simple juxtaposition of differentiated elements to be viewed in their functional and, in the final analysis, constructional connection.

Viollet-le-Duc saw the development of the capital as a sure indication of the process of scaling down the supports, the isolated fulcrums, in the scheme of the composite pier, which was designed as the pure and simple extension of the springing of vaults that characterized the evolution of Gothic architecture at the point of its maturity (if he is to be believed). In his article “Capital,” we learn that in the twelfth century Île-de-France, the capital appeared as “anintelligent extension of the shaft,” and so took its supporting functionsseriously.6 (Note the shift of attributing to the building, or at least to a particular part of it, some of the intelligence and seriousness that Viollet-le-Duc sees in the builders—a kind of inverted empathy.) The form of the capital is determined in the Gothic system by that of the springer, which corresponds to the springing of the vaults, any modification of which will necessarily affect that of the pier, which thus could not maintain its circular cross section. If we consider the column as a structural unit, one that puts into play a series of discrete elements (the transformations of which have consequences for the functional equilibrium of the whole), then the decline in the role assigned to the abacus and the evolution of the Gothic capital—which was itself gradually reduced to a simple band of foliage and ultimately eliminated—are signs that, even if the column played a seminal role in the original system, in the end it would lose its place, for its characteristic mode of articulation openly contradicted the structural principles of Gothic architecture in its final and, logically speaking, consummate form.

Such an assertion sheds light on the problems posed by the deployment of a given structural or functional unit in a context that is itself specified by name, as well as on the relationship that unites the column as a singular form with the other “units” that the art of building puts in play. Having defined the column as an articulated whole to which the role of vertical fulcrum has been devolved, Viollet-le-Duc hastens to insist that the form is not amenable to an indefinite number of combinations and that, strictly speaking, it can be linked to only two other well-defined members of architecture: the lintel and the arch. And so his analysis focuses at the outset on already structured elements, functional units identifiable as such. But it follows immediately that, though the column can be defined as a singular form, a discrete unit, in its internal articulation, it obeys a principle (if not a law) that endows it with use-value together with relatively limited constructional valences. A column cannot be utilized gratuitously, nor can it be used in any context whatever or separated from its function; its structure permits change only within very strict limits, beyond which the column as such does not exist.

This raises another question: should we exclude from the category of “column” any architectonic member that corresponds to theDictionnaire definition on all points but one—namely, that it supports notone butseveral arches? This question is neither superficial nor sophisticated; to confirm this, one need only read the pages devoted to the question, and the distinction between being and appearance arises once again. Indeed, the structure and perhaps even more so the form of the column is not entirely suitable for supporting oblique pressures without the risk of leaning. You might say that all that is needed to reestablish equilibrium is for the thrust of an arch to be countered by the thrust of an opposing arch, the column supporting not one but several arches that buttress each other. But the vertical force resulting from the oblique pressures would be so great that the column would have to be displaced by a much bigger pier whosescale (not “proportions”) would be such that we could no longer call it a column. Thus, despite theDictionnaire’s ostensibly descriptive and historical definition of the column, there remains a basic incompatibility between the column and the arch, as well as between the column and the vault. It is no coincidence, moreover, that the article on scale gives us the clearest statement of a contradiction that is obviously not just functional: “Since the lintel is no longer acceptable, the fulcrum is no longer a column; it is a pier.”7 By 1220, “French architects, had ceased using the monocylindrical column for bearing vaults and sought continuously thereafter to transform the column into a support for the projecting members of the vault, and thus into a vertical beam for those members.”8 The process came to an end, even before the close of the century, in a building whose precocity has often astounded archeologists: the Church of Saint-Urbain in Troyes. Since then, the pillar has presented a section that corresponds “logically” to the cluster of arches that descend and without interruption or rupture (solution de continuité) from the top of the vaults to the ground.

Many of the theoretical problems I have just evoked echo those encountered by structuralism as it was developed more than a century ago in the human sciences, beginning with linguistics and anthropology—and in constant opposition to functionalism, which, as the term indicates, puts function ahead of all other determinations. When, in the preface to a selection of extracts from theDictionnaire,9 I tried to demonstrate why Viollet-le-Duc should be considered one of the initiators of structuralism, I was accused of having yielded to the seductions of a peculiarly Parisian vogue—but in fact there was no retrospective projection involved. For we cannot ignore the fact that structuralism was not invented in 1950s Paris and that it already had a long history behind it, beginning long before Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roman Jakobson, or even Ferdinand de Saussure. In this context, Pierre Francastel deserves credit for recalling the constructional ancestry of the concept of structure. In the case of Viollet-le-Duc, the work of Philippe Boudon and Philippe Deshayes on the “Raisonné” (as Frank Lloyd Wright called theDictionnaire) confirms the thesis I put forward, to the great displeasure of some.10 Today, if we are to believe the rumor, structuralism has gone out of fashion—something that can only be a cause for rejoicing—yet I am all the more comfortable insisting on what I said before, even if it means once again displeasing those who do not appreciate seeing art history risk involvement with thought. This is not to say that Viollet-le-Duc could not have known Saussure’s name, which was also the name of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, great-grandfather of the author ofCourse in General Linguistics, who in the eighteenth century made a famous ascent of Mont Blanc, a feat recounted in hisVoyages dans les Alpes. Following the Lausanne exhibition on Viollet-le-Duc in 1979, the exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1980 reminded us of Viollet-le-Duc’s keen interest in the architectonics of the alpine massif, an interest that was obviously connected to his intense passion for architecture in all its forms, including the natural. This passion was equaled only by Saussure’s drive to confront language in terms that Lévi-Strauss would make use of when he identified an architecture of culture similar to the architecture of language: “Language can be said to be a condition of culture because the material out of which language is built is of the same type as the material out of which the whole culture is built: logical relations, oppositions, correlations, and the like. Language, from this point of view, may appear as laying a kind of foundation for the more complex structures which correspond to the different aspects of culture.”11

I wish to conclude with a comment on theory and its evolution, its ebbs and flows. In the domain of anthropology, the structuralist hypothesis came in part from reflections on the contradictions of functionalism. Viollet-le-Duc himself emphasizes the idea of function throughout his work, and yet the idea is never unequivocally defined, either in theDictionnaire or in theEntretiens.Function at times refers to the constructional value or utilitarian purpose assigned to a particular architectural member or form and at others is used to characterize the relative arrangement of architectonic elements within the same constructional organism. Indeed, it seems that, by placing more and more emphasis on the “needs” answered by the work of architecture, Viollet-le-Duc, inEntretiens, took a step back from the theoretical argument of theDictionnaire. Whereas the latter sees architecture as subject not to staticstates but to an uninterrupted series of transitions, the former exhibits a more strictly functionalist turn, whereby the role of historical creativity is displaced by a so-called common stock of eternal principles held independent of the forms that express or betray them. In matters of architecture, Viollet-le-Duc concluded, we can no longerinvent but merely “submit known elements to analysis, combine them, appropriate them.”12

The example of the column is provided once more inEntretiens and thus attests to the relative decline in a doctrine that, having failed to preserve the full epistemological scope of the concept offunction, would end in a form of utilitarian empiricism that clearly contradicts the structuralist intention of theDictionnaire. Indeed, Viollet-le-Duc ofEntretiens does not hesitate to conclude that if the Doric column has no base, this is because a base would get in the way of the passing public and insult visitors’ feet.13 Yet his theoretical retreat is most obvious when he treats the form of the shaft. TheDictionnaire article “Scale” in fact develops a notion that would interest advocates of a “nonstandard” architecture: the notion of apier articulated at the base. The idea of giving a pyramidal or conical form to a pier that supports even, symmetrical forces cannot be conceived by a true architect, for any builder (as Viollet-le-Duc asserts) knows that all one needs is an upright pillar that allows for the anticipation of errors in the calculation of forces, insofar as it can pivot on its base to return the resultant of the stresses to the vertical. Yet what do we read inEntretiens? “No one will allow that a column, a vertical fulcrum, can be more spindly at its base than at the top.”14 A question, one could say, of empathy. Philosophers are well aware that no matter how opposed rationalism and empiricism may be in principle, they are not averse to swapping roles occasionally. It is only all the more remarkable to see our inveterate rationalist, in an appeal to common sense, take up the example David Hume used a century earlier to illustrate the idea that the rules of architecture have their basis in sensory experience. As Hume wrote, those rules require “that the top of a pillar should be more slender than its base, and that, because such a figure conveys to us the idea of security, which is pleasant; whereas the contrary form gives us the apprehension of danger, which is uneasy.”15

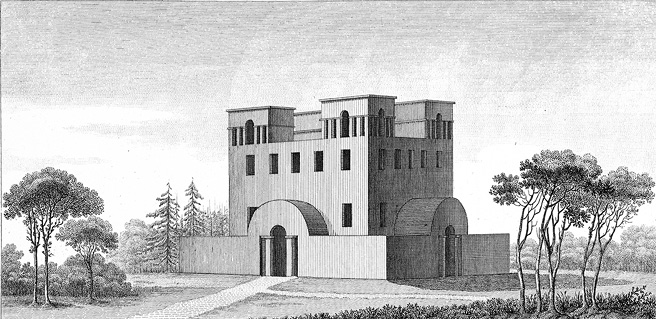

7.1

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, Country House for a Man of Letters (Abbé Delille), perspective view. FromL’architecture considerée sous le rapport de l’art, des moeurs et de la législation (Paris, 1804), plate 69. Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.