8 L’Autre “Ich,” L’Autriche—Austria, or the Desire for the Void: Toward a Tomb for Adolf Loos

Translated by John Savage

Warum haben die papuas eine Kultur und die deutschen kein?

—Adolf Loos

A city, said Adolf Loos, has the architects it deserves. This remark raises a question: should we credit Imperial Vienna, “Vienna 1900,” and later the democratic, republican Vienna that trusted Loos for a time to direct its municipal housing office with producing and giving sustenance to a man who, in his actions as well as his writings, never stopped denouncing the status given to those who aspired to the title of architect in the capital of theöster reich, a title that was at best dubious in his eyes? This polemicist is known more today, even in Paris, for the role he played at the beginning of the twentieth century in the campaign against ornament than he is as the author of Tristan Tzara’s house behind the Butte Montmartre. If we conclude that Vienna did not “deserve” him, why did this architect (who was one so rarely) not expatriate himself to the America so many of his colleagues had simply refused to visit but that he, in contrast, had traveled to the moment he left school, and his precocious discovery of which was paradoxically to make of him, once back in Europe, a kind of stranger in his own land? Was Vienna really so necessary to him? Why was this true, and to what end?

The Potemkin City

Vienna, for Loos, was first of all a “Potemkin” city: a city that hid its true identity, its nature, its class reality, under the clothing, the rags made for it by its architects, just as Catherine the Great’s favorite had erected whole trompe l’oeil villages made of cardboard and cloth on the desert plains of the Ukraine for the visits of the empress.1 This Austrian Potemkin city razed the belt of its medieval walls only to raise a new ring in its place, made this time of a series of false palaces, rental buildings given the look of the princely residences of the baroque or Renaissance eras: an architecture of the mask, deserved by a capital that sought to preserve aristocratic appearances into the bourgeois age and that assigned its architects the task of dissimulating all social distinctions among its inhabitants, at least in the better neighborhoods, under the camouflage of false broadstone decorated with elements patched together with cement (the problem of working-class areas was only posed later, once Vienna turned “red”). It was a trompe l’oeil architecture that Loos considered “immoral” because it was founded on lies and imitations (the “substitute”) and because it was born of a sense of shame. The materials themselves lied, mimicking the signs of a bygone era. The shame did not come from being poor, as Loos writes, but if one was well-to-do, like a bourgeois living on thering amid the banks and luxury hotels, then there was the shame of not being among the wellborn, the shame of having to accept oneself as one is: a bourgeois, a man of one’s time, a “modern” man.

8.2

Adolf Loos, Tristan Tzara House, Paris, 1925–1926. © Albertina, Vienna.

Art, Architecture

But modernity itself was still tied to clothing in general—and to the mask. From the beginning, just after the creation of the Secession (the Austrian version of art nouveau) with the help of the state and in the prestigious shadow of Otto Wagner, the tone was set by a series of articles on the Jubilee Exhibition of 1898 organized around the themes of clothing (Kleidung) and cladding (Bekleidung), and by the first work of Loos the architect: the construction of Goldman’s men’s fashion store in Vienna. A tone, one must say, that was anything but revolutionary, even if Loos had little patience for authority in any form (and did not hesitate to make this plain). The tone was that of an architect who saw himself as modern—that is, of his time. A few years later, anticipating in his own way Karl Mannheim’s opposition between ideology and utopia (which was itself ideological), Loos would not hesitate to write that if art, the work of art, has a revolutionary vocation, then the house is conservative (the house, not architecture, because the latter does not only produce houses, but also monuments and tombs, toward which—as we will see—his art ultimately evolves and to which it limits itself). “The work of art is revolutionary; the house is conservative.”2 The work of art is turned toward the future; it opens new paths for humanity, on which the building is of its time and “thinks” in the present tense. In this sense, if the work of art (and the tomb itself, the simple burial mound where class relations dissolve, as well as the “monument,” which pushes them to their limits) can have a utopian meaning and function, if it can transcend “the given” and aim to break the bonds of the existing order, then the “house” is on the contrary fully inscribed in the register of ideology, of consolidation, of the confirmation of reality. In contrast with the work of art, whose impact extends, by right, to “the last days of mankind” (“bis in die letzen tage der menschheit”3), the house responds to a current need; it is in the service of a present use; it has nothing to do with art; it must please everyone: man loves the house; he hates art. However, it is for this very reason that he cannot adapt to a home conceived for him by an “artist,” even a member of the Secession, short of wearing it like a borrowed piece of clothing. A house, an apartment, lives and transforms itself with whoever lives in it. It must tell a story, that of an individual or a family, not bear witness to the art of he—whether designer, architect, or soon, as Loos predicted, sculptor or painter—who starting from this usurped position is capable of exercising an unbearable tyranny over both members of the building trades and his clients.

The Principle of Inconspicuousness

But why would everyone not live like a king if they had the means (and this despite the fact that, or all the more so because, due to a contradiction that did not escape Loos, kings had lost their sense of splendor and were now living like everyone else—in other words, like bourgeois)? As for clothing, which Loos would always associate with the question of housing, did he not suggest that one can judge the level of a country’s culture by the number of inhabitants that used their newly acquired liberty to dress outside of any set hierarchical norm or constraint—even, if they felt like it, like the king himself? Proof of this was found in Anglo-Saxon countries, where “everyone” is well-dressed, as opposed to Germanic countries, where only members of high society are. But what does well-dressed mean, exactly? It is to be dressed in the least garish way possible. Moreover, we must be clear: an Englishman would not go to Peking dressed as a Pekinese, nor to Vienna as a Viennese; that is because in his view he has reached the height of civilization. In its complete, fully developed form, the “principle of inconspicuousness” betrays a radical ethnocentrism. To be well-dressed is to be dressed in such a way that one stands out the least when one is at the central point of culture—that is, according to Loos and at the time he was writing (because a center is always subject to displacement), in London and (at the risk, even in that privileged place, of having to change at every cross street)in the best society. “An article of clothing is modern when the wearer stands out as little as possible at the center of culture, on a specific occasion,in the best society.”4

8.3

Adolf Loos, Goldman and Salatsch Menswear Store, Michaelerplatz, Vienna, 1909–1911. © Albertina, Vienna.

Being Outside

It is thus due to its calculated putting into perspective that Loos’s discourse, if not his architectural practice, took on a critical function and impact beyond the Viennese context. This was true to the point to which—through the encounter with Tzara as much as by the singularly corrosive tone of his own writings (which, for once, did not escape the attention of “advanced” Parisian circles5)—an aura of avant-gardism became attached to his name, one that was perhaps dubious, but by the same token very revealing of ideological contradictions whose interplay allowed the encounter of Dadaist negation and the constructive propositions of the modern movement in the pages ofL’Esprit nouveau as well as at the Weimar Bauhaus. If Loos felt that he was speaking into a void (as suggested by the title of his first collection,Ins Leere gesprochen, which was published in Paris before it was in Vienna), it is because in reality his discourse needed a void in order to produce its effects, in order to be produced. It was not enough for Loos to recognize the existence of this void, to mark the difference, the gap between the predominantly Anglo-Saxon state of things that prevailed in the West and the culture (or its absence, the lack of culture; we will see how to understand this) that, according to him, characterized Germanic countries. It was necessary to constitute it as a place, a space from which his statements were generated by an operation that, if we look closely, is the source of all his undertakings, whether in the ideological (literary) sphere or in architecture. An operation, we might say (and Littré wished us to speak in this way, to save an indispensable word from obsolescence), by which the ego is estranged from itself,6 establishing itself in a position that is outside, if not eccentric, relative to itself, to the point of taking on the discourse of the other.Das Andere: once again, the title is explicit. It is the journal that Loos undertook to edit in 1908, inspired by his friend Karl Kraus’sDie Fackel (The Torch), in order “to introduce Western culture to Austria” (since that was the subtitle of the publication, which lasted only for two issues). If Loos needed Vienna, it was because Vienna, alone among Western capitals, located as it was in the center of Europe “where the world’s old axes cross,”7 made a fiction into reality: that of a circle (thering) that is such a perfect void—in the grammatical sense of the word—that the very question of the “center” had to be asked from a position of exteriority, of alterity.

The Place of the Other

Das andere, the other, the other ego,l’autre“ich,” Austria, the ego that is other, theöster reich, the Eastern power, Vienna, soon to be “red” (the Orient is red), a fictional place, a place of fiction and as such open to all sorts of operations on the notions of subject, of identity, of centrality (of point of view), if not of quality: this is Freud, of course, and on a more modest level (but a modesty that had nothing innocent about it), Loos himself. (To say nothing of Musil, who pretended not to give any particular significance to the name of “the” city. It is true that to ask of the complex entity that is the city in which we reside which particular city it is, from the point of view ofThe Man without Qualities, is to be distracted from more important questions.8 But what other city could Musil have pretended had no name? What other city, if not Vienna, taken as the vaguest of generalizations, as an ellipsis, a grammatical void?)

Modernity and the Role of the Mask

“Certainly the artist is The Other. But that is just why his appearance should match the others. He can only remain solitary if he disappears into the crowd. . . . The more entitled the artist is to be different, the more it is necessary for him to clothe himself in the everyday, like a mime.”9“Anyone who goes around in a velvet coat today is not an artist but a buffoon or a house painter. We have grown finer, more subtle. The nomadic herdsmen had to distinguish themselves by various colors; modern man uses his clothes as a mask. So immensely strong is his individuality that it can no longer be expressed in articles of clothing.”10

Modernity implies as its condition, if not as its sign, that the role of the mask be reversed. Indeed, where in archaic societies the mask confers a social identity on its wearer, inscribes him in his place in society, modern man on the contrary uses it to hide his difference, his otherness (just as the artist himself, the otherpar excellence, whose speech always draws on the collective unconscious, but who does not know how to be “modern” as such, both because the unconscious has no history and because in creating a work of art, a work turned toward the future and the end of time, the artist is not of “his” time). Even professional revolutionaries have recourse to this trick, and H. G. Wells was right to say he was wary of Lenin wearing a waistcoat.

This paradox is a matter of class; it should be understood as a paradox that within a class structure leads to an unmasking. The paradox is that, in the Viennese void, the denial of sartorial signification, of clothing as a sign, itself functioned as a sign and was thereby used as such: inconspicuousness (nondifference) became a mark of distinction (of difference). To be honest, it certainly did not bother Loos to be able to write that the greatest tailors of Europe were found in Vienna and that he was their client (it is by the way for one of them that he undertook the Michaelerplatz building). According to Loos, these were real artists and thus, working for a chosen clientele, they avoided all publicity. When the occasion required it, they showed only those clothes that could not easily be copied or imitated. Nothing was more misleading as a result than the “class” of a piece of clothing, in a context in which the aristocracy dressed the way the bourgeoisie should and parvenus wore false fronts and tails. There is never “class” or “style” but for one class, the only one that can be stylish (or have class), where historical epochs never have but one (or several) style(s).

But the tendency of the bourgeois class to confuse its own interests with those of the whole of humanity leads to an unprecedented diffusion, circulation, and exchange of signs (and styles). All clothing is deceiving, and cladding is by definition all the more so as a matter of principle. Even if he is as “smooth” as the Viennese cigarette cases Loos liked so much, a well-dressed and short-haired man should still not be judged by his looks (or his waistcoat): “All that is smooth is not necessarily modern.”11 All of this is another way of saying that in class society, the lack of ornament can still be an ornament; it can assume that function as an absent signifier. In the same way, a steak served plain (without condiments) can take on the value of a sign: a sign of modernity, a sign of “class.”

Ornament and Crime

The campaign waged by Loos against ornament (ornament, if not “the fine arts,” considered as crime) was one that followed a calculation, a deliberate strategy. But this strategy implied within itself a counterstrategy. In games as in war, and in the game of art as in the struggle among men or the war between the sexes, strategies go in pairs. And if, in theory, a strategy must include in its definition the strategy of the other, this is necessarily otherwise in practice. As in games, strategic struggles,the strategy of the other is the unconscious. Loos’s trick was precisely that he set himself up (at least fictionally) in the position of the other; he inscribed his discourse, his strategy, in the name of the other. Struggling to introduce Western civilization to Austria was a way of trying to loosen the repression that made a society—a newly bourgeois city like the Vienna of Loos, Kraus, Musil, but also Freud—refuse to recognize itself in the mirror held up for it by Western cities and to seek in ornament the means to sublimate—in every sense of that word—the most mundane capitalistic drives. A means of sublimation, Loos would say, that represented a veritable crime against the economy, in that it meant a double waste of both raw material and work—that is, in the end, of capital. None of this stopped the Austrian state from supporting the decorative epidemic (of which the Viennese Secession constituted one of the final symptoms) with subsidies while waiting for the hour of the Deutscher Werkbund and the Bauhaus, where one could observe artists working to perpetuate the alliance between art and artisanry that Loos thought went against nature. But that is because the reason of state is never directly modeled on that of capital. If the state works to slow cultural progress, it is because it is founded on the assumption that an uneducated people is easier to govern.

8.4

Adolf Loos, Moller House, Vienna, 1927–1928. © Albertina, Vienna.

For Loos, cultural evolution followed a simple law, which was synonymous with the progressive removal of ornament from objects of daily use, starting with the foremost among these: the human body. The apparent fascination that the practice of tattooing held for Loos, while normal for a Papuan,12 had in modern society become (according to Loos) the privilege of known or potential delinquents,13 as well as a certain aristocracy (e.g., the “dueling marks” then so prized by German students); it is to be considered alongside of the no lessfascinated status ascribed to “art” in his discourse. If it is true that Loos’s comments on the house, conceived of as an object of daily use, contributed to the desacralization of architecture (heretofore reduced to being practiced as art only in cemeteries), this is not true of art, which as we have seen by definition escaped both from common law and the imperatives of modernity (in other words, of capital) and represented in fact—if only under the most revealing category of the tomb—the last refuge of the sacred. If art, as the era would have it, originated in decor and if, following the example of body painting or the decoration of a pot, it appears at first as an addition, engraved on a support, on apreexisting body, then the surplus that it adds is far, at first, from coming from the “soul.”

Figure 8.5

Adolf Loos, Moller House, Vienna, 1927–1928. View of hall and stairway. © Albertina, Vienna.

The simplest, most elementary mark—the cross—was interpreted by Mondrian in a mystical sense before Le Corbusier saw in it minus by minus, the sign of positivity; this mark brings together the masculine and feminine elements in the coitus of vertical and horizontal.14 This is to say that for Loos there was no art but erotic art, linked in its very principle to basic drives. But if, as Freud teaches us, the progress of civilization demands repression, the denial of these drives, it does not lead to the elimination of any possibility of substitutive satisfactions of the kind that art, in its highest forms, is able to procure. In its highest forms—that is, under the condition that the artist renounce ornamentation—it is that derisory variant of elemental drives that made primitive man smear erotic lines on the walls of his cave, in the way that still today “delinquents” and “degenerates” cover the walls of public lavatories with obscene graffiti: in the way (but this Loos could hardly have written) that the painters of the Secession, starting with Gustav Klimt, covered the ceilings of university buildings and the walls of Vienna’s theaters and museums with frescoes in which decorativeoverload was put in the service of an eroticism that, while never drawing on the illusion of “flesh,” only better revealed the prestige of the ornament adorning the paint (a purely symbolic prestige, in fact linked to the obliteration of the body). “One can measure the culture of a country by the degree to which its lavatory walls are daubed.”15

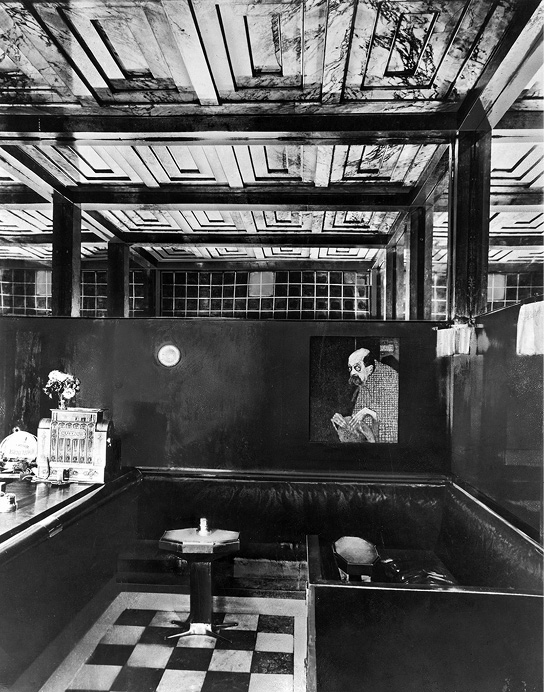

8.6

Adolf Loos, Kartner Bar, Vienna, 1906–1907. © Albertina, Vienna.

Division of Labor

Ornament, if not art itself in its original, decorative,applied form, therefore functions as the repressed, posed as such in Loos’s discourse. Even better: it is only by starting with this discourse and through its operation that ornament takes over the role of the repressed. It remains to be seen in what form the repressed element surfaces in Loos’s own work. In fact, even though he didn’t build much (a few private residences and, along with a number of remodelings, the Michaelerplatz building, erected—blasphemy of blasphemies—opposite the monument to the “Power of Austria,” by one of the masters of the Secession, Edmund Heller), the very project of an architecture that owes most of its effect, its prestige, to the combination of an honest use of materials and in contrast a totally arbitrary use of form (following the model established in the realm of sound by so-called serial music) was also not above drawing some of its power from the very thing it claimed to exclude. If only Loos had planned the decor (but a decor owing nothing to ornament?) of enough stores, cafés, and private apartments to justify the whole weight of the affirmation according to which the task of the architect should be reduced to enclosing walls around a void, which it would then be up to its inhabitants tofurnish, with the help of carpenters and upholsterers who do not need to be told what to do by an “artist.”

It is here in Loos’s text that the postulate comes to light that led him to denounce the efforts of the Werkbund, and later the Bauhaus, to define the conditions of art’s intervention in the process of industrial production. For this apostle of the “American way of life” (of everything from eating eggplant to wearing one’s hair short) held on, in matters of social organization and cultural hierarchy, to the traditional opposition between art and artisanry, between the work of art and the object of daily use. “God makes the artist; the artist makes the epoch; the epoch makes the artisan; the artisan makes the button.” In other words, the artist and the architect himself (all architects dream of being a bit of the artist, and Loos was no exception to the rule) had better things to do than aspire to oversee the production of buttons. Loos’s idea was that every epoch, including the modern era itself, has by definition at its disposal objects that are appropriate to it: furniture, utensils, and so on. If an object or piece of furniture breaks this rule, we can be assured that the fault lies with the untimely intervention of some master of academic or industrial aesthetics. The sketch of a critique of ideology, and still more of design practice, that we can glean from his writings falls heavily under the category of degeneration, of cultural void. “Mankind’s history has not yet had to record a period of non-culture. The creation of such a period was reserved for the urban dweller during the second half of the nineteenth century.”16 We are to understand this as a critique of an urban structure that had become one of the sites, one of the instruments of the accumulation of capital, in which neither the artisan nor the architect could be employedas such. Loos’s revulsion at the idea of taking into account the changing scale of urban development problems (obvious even in his mass housing projects of the twenties) goes hand in hand for him with the idealization of artisanal conditions of production. In this archetypal site of “alienation” that is the large modern city, the architect is never but an uprooted person, just as, in their own way, the abruptly proletarianized peasant masses are. The best he can do is limit himself to specific projects that he attempts to insert unscathed into the urban fabric; a program, as we can see, that is very timely. It is the same one that was behind the Michaelerplatz building, which was scandalous because it made any usurped signs of familiarity, as well as any plagiarism, impossible. In contrast with the baroque palaces, the columns of the ground floor are monolithic and made of real marble.

But what of the artisan? To pretend that left to himself a carpenter could not help but produce furniture that is perfectly adapted to modern housing conditions (if only the architect would let him do as he sees fit), just as a cobbler’s shoes are adapted to their use, is to forget that the architect’s efforts to make the different members of the building trades conform to his vision (and his interests) are themselves an integral part of the constant process of restructuring the division of labor of which the architect is, in his turn, a victim. The English furniture and Thonet chairs that Loos appreciated so much were not produced by artisans, but by industrial means. The real question, the one Loos stopped himself from asking, is there. He did his best to repress it by dressing himself up in an altogether characteristic “aristocratic” attitude. Are the mechanisms of industrial production so perfectly rational that letting them play out “naturally” allows us to expect the bestqualitative results? Industry as second nature: that is the implicit message, the unsaid of the liberal ideology of laissez-faire, the actual place from which it is speaking. It pretends to give voice to the other from behind the mask of the first person, but the other cannot establish itself there.

The Law of Cladding

If the profusion of primitive decor is the response, in the traditional interpretation, to thenatural horror of the void, why would culture—but a culture that is highly sophisticated, urbanized, and antinatural—not play on this void (as others played with velvet) until it could extract from this “horror” and from the desire that is its reverse the basis for new pleasures (jouissances)? (This while still giving itself the luxury of simultaneously enjoying the most archaic of products, productions of theother whose discourse Loos will not have neglected, but under the condition of clearly noting the place, the unconscious. A Maori sculpture, like a Corinthian embroidery, is part of our culture’s unconscious, a culture that is such avoid that a Thonet chair can itself be listed in the category ofoutsider, if not of the eccentric.)

But if it was true that Loos liked to take as a point of comparison the peasant who builds his own house according to what he needs, without thinking about it, he was far indeed from advocating the return to a “rural” architecture that would become one of the themes of Nazi propaganda. He had learned from experience that an architect cannot help but work against nature. When he wanted to use lake stones to build his first house in Montreux, was he not accused of desecrating the site’s majesty? (But that day, as in the case of Michaelerplatz, the police summons gave him the delicious feeling that he was an “artist.”) What is left is to use materials in the most honest, the most just possible way. The law of cladding forbids us to give one material the appearance of another, and especially one of higher quality than its own (“false wood”). What is unbearable is not to see the aristocracy dressed as bourgeois, but that the bourgeoisie tries to imitate it down to the smallest signs. We may well all be made of wood from the same forest, but the wood is not all of the same quality. (What, then, would Loos say of the particleboard that industry gives our carpenters to dress up under thin layers of fine wood?) Loos’s taste for materials, for thetactile aspect of construction and interior design, comes from his need to define the conditions of a new architectural culture within the cultural void of the modern city. A culture no longer founded on ornamenting, but on cladding, which is the basis for all architecture (which, from the start, was never anything but an extension of clothing, in the way we might think of an umbrella). Loos took great pride in having introduced panels of polished marble or pounded copper in interior decor. The look that banks in Zurich, Milan, or New York have now is designed to give the impression that the boundary between ornament and cladding is undetermined and that from one to the other a switch, an inversion of signs is always possible. Is not to clad still to mask, to dissimulate, to mislead, if not—though with the proper “inconspicuousness”—to ornament? In fact, Loos’s architecture is, in its own way, an example of the “drama” of modern architecture that Manfredo Tafuri has characterized best: an architecture reduced to wishing itself pure, a strictly formal exercise, deprived of utopia, useless, but nevertheless preferable to projects that are clad in ideological rags but in fact serve the reigning order.17

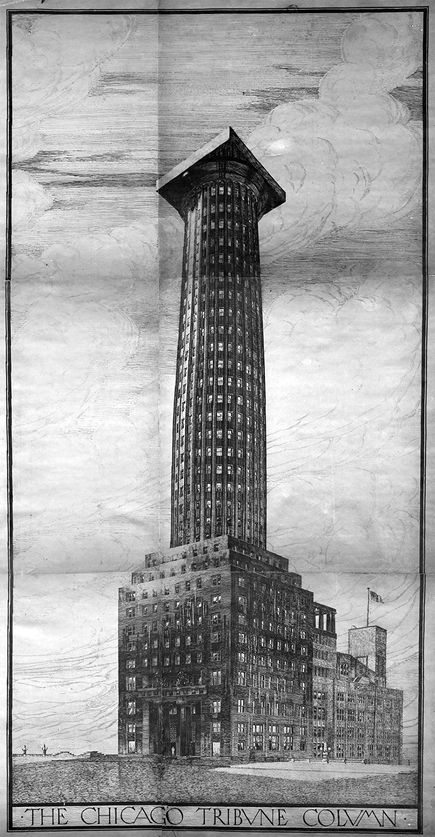

Tomb

It is here that we find the confirmation, by a new paradox, of Loos’s project for the Chicago Tribune of 1922. This project, a skyscraper of more than thirty floors in the form of a Doric column set upon a high cubic pedestal, not only represented (as Tafuri understood) the first manifestation of “pop” culture and the announcement of what were in the end the far more modest “monuments” of Claes Oldenburg.18 It also corresponds to utopia in its purest form and function, that of the dream which, in order to satisfy desire, knows to play systematically on contradictions. The edifice was to be “the most beautiful and the most characteristic of the world” (as the program of the competition had it). To use the figure of Trajan’s column constituted a risk that the sponsors did not know how or did not want to take. There is no way to avoid the funereal significance of such monuments, made as they are to be torn down (and revolutions, as we know, sometimes succeed in doing so).

This project, like the one for Josephine Baker’s house (in which a transparent glass cube forming a swimming pool would have constituted the core), allows Loos’s obstinate words to assume their full proportions, which are of a totally different scale than the problems architecture seems to struggle with today. Loos affected the belief that one of the principal contributions of the architecture of his time was to teach plumbers and carpenters how to hide a flush toilet under wood-clad paneling. “When we come across a mound in the wood, six feet long and three feet wide, raised to a pyramidal form by means of a spade, we become serious and something in us says: somebody lies buried here.This is architecture.”19 It can still happen today that, entering a bathroom, we notice that the sanitary installation is made in such a way that the evacuating mechanism is hidden from view. Adolf Loos would have wanted no other tomb than that one: a tomb that combined in its arrangement and structure the functions of cladding (the pleasure of tactile appearance) and, hidden away, of evacuation (the desire for the void, in its anal connotation, that characterizes the reign of money). Such a tomb would be in the very image of the pleasures created for everyone, down to the most disinherited, by the modern city, the capital of capital; pleasures that Loos was not, for his part, prepared to renounce. A flush chain in his wooden coffin or his marble (or pounded-metal) catafalque:Das ist Architektur.

8.7

Adolf Loos, Chicago Tribune Tower competition entry, 1922. © Albertina, Vienna.