11 The Slightest Difference: Mies van der Rohe and the Reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion

I don’t like to saycolumns, the word has been spoiled.

—Le Corbusier,Toward an Architecture1

On the initiative of the architect Oriol Bohigas, who presided for many years over Barcelona’s municipal building programs, the pavilion Mies van de Rohe designed to represent Germany at the 1929 International Exhibition (which had immediately been destroyed when the show closed) has been reconstructed. For decades, the monument existed only on paper, in the form of a folder of period photographs and a few sketches and preparatory plans (now kept at the Museum of Modern Art in New York), together with a welter of miscellaneous commentaries, but in 1986 the Barcelona Pavilion was returned to us in concrete and marble, glass and steel (we would say “in flesh and blood,” if it were a person) on its original site at the foot of Montjuïc, with all of the attendant consequences in terms of both its reception and Mies’s work as a whole.

Today, engaged as we are in a general revisiting of the values of modernity—the same values found in the Barcelona of Cerda, Gaudí, Sert, and Bohigas, but also of Picasso (the return of the pavilion does not sit well with the caricatural critique of the “postmodernists,” who have too quickly condemned the limits and even the alleged bankruptcy of “modern” architecture)—what might be the meaning of such an operation? And what might be the impact of the reconstruction of the most emblematic work of this particular master of the modern movement (who perhaps represents the hardest, most imperious, and most intransigent core of that movement) and, for those who confuse architectural criticism with the criticism of ideologies, also the most intolerable work? Beyond the coup for local commerce and tourism, should we see it as a profession of faith, reiterating anew the message of Mies’s 1929 architectural “manifesto”? Or would it be rather a call to order (Let’s not let ourselves be taken in: modernity is not, or is not only, or exactly, what they would have us believe), or even a way of fending off a certain critical discourse that sees in Mies’s oeuvre a mere series of “empty prisms,” characterized by the reduction of the image, pure form without content, set into invariable types? These same supposed “empty prisms” have tended to work as symbols, if not symptoms, through a characteristic rhetorical reversal, to the point at which they have embodied what Manfredo Tafuri describes as “the fantasies of European intellectualism.”2 For a French intellectual like myself, who made the trip to Chicago at the beginning of the 1960s burdened with the images of the architectural press and influenced by Tafuri (who worked hard to give architecture the place it holds in contemporary culture), that “fantasy” could not fail to be striking. As may well be, in the current context, the reconstruction of a mythical monument par excellence that looks to have, once again in the order of reception, a semiexperimental scope.

I spoke of a “monument,” but amonument in what sense? Its construction long planned with the consent of Mies himself and carefully prepared, reflected upon, even orchestrated, the reintroduction of one of the lost prototypes of the so-called International Style into the built environment does not appear to be precisely a return of the repressed. In fact, the “identical” nature of its reconstruction might have posed a greater problem, meeting with resistance on a number of fronts (to say nothing of the cost of the endeavor, a factor that also weighed heavily on the fate of the original building). The influence of the pavilion was felt from the very outset, the latest round of debates on modernity having little impact. There is no history of architecture, no matter how “critical,” that does not give the Barcelona Pavilion a special place, value, and significance as an example to be followed. If we can apply the wordmonument to it, merely on the strength of having seen a few graphic documents that recreate its appearances (with the ambiguous authority typical of architecture photography) and allow a reasoned analysis of it based on the floor plan, it is because the trace it has left in the archive or memory of the modern movement corresponds, historically as well as formally, to a kind of successful “clean-up operation.”

As unusual as the pavilion was and remains, in principle and in practice, the vicissitudes of history having conferred on it an almost ideal, even mythical, value (even if photography attests to the reality of its provisional existence), this object has never stopped functioning simultaneously as a paradigm and a memory device. As a paradigm, it worked to propose, at the reduced scale of a relatively light single-story structure, a schema for declining and conjugating the parameters of the architecture that we correctly hold to be characteristic of a certainmoment of modernity. As a memory device, if a paradoxical one, it conjured up a memory of this moment (all the better to cover its tracks) so that such a schema seemed to overlap with proposals put forward in fields outside architecture—notably, painting and sculpture. This seemed to imply the serious revision of the boundaries between practices, the specificity of which was obstinately stressed by the modernist ideology, while at the same time admitting that such practices might share a common denominator, as in the mandatory first-year course still taught at the Bauhaus for all students (whether they wanted to go into painting, sculpture, architecture, ordesign) at the time Mies was about to become head of the school, a year before the opening of the Barcelona exposition. One of the issues the Barcelona Pavilion raises, the subtlest perhaps, ultimately bears on the limits (which I would call disciplinary) of a history of architecture and especially of modern architecture on its conditions of possibility and on the meaning, in this instance, of the wordhistory. It is not certain that now having at our disposal an “identical” reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion will help us get a clearer picture of this.

The reconstruction (or should we say reproduction?) should at least lead us to reflect on the diverse species or modalities presented by the architectural object. In this regard, Mies’s oeuvre does not escape the common rule: any overview that one might offer presupposes that we compare terms that are not necessarily of the same nature, or even the same level. Whether we are dealing with the spectacular projects for transparent office blocks designed for Friedrichstrasse, from 1920 to 1922, the residential tower blocks built on the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago from 1948 on, or, within a narrower time frame, the 1923 Brick Country House project that Mies built a few years later at Guben and Krefeld, the connections risk being misleading, as much on an aesthetic as on an ideological level, as we will later see. In another register and to a lesser degree, the comparison between the prevailing image of the Barcelona Pavilion in the architectural press and the reconstruction offered to us today might also be misleading—even if the only reason for the uneasiness the operation is likely to cause is thegap, which some will see as insurmountable, between the mark left by the prototype on the imagination and its rediscovered reality.

What was it about the prototype, then, that the fact of reconstructing it, of reproducing it (almost) identically, is enough to change its meaning—or at least to alter its impact, in the same way that a new edition of a bronze sculpture can lead to a shift in the way we look at what was held to be the original? How can the very thing that makes for its originality (which no one is contesting) be affected by itsreplication? It has often been noted that the Barcelona Pavilion registers a break with the archetype of the primitive hut, of the house conceived as a cube, a closed box. If “shelter” there is, it is in a quite different sense, one illustrated today by the windbreak shelters erected at bus stops, or at a particular service station in Montreal, which was once presented to me as being by Mies (or his atelier), but which monographs and catalogs routinely fail to mention. In the absence of the glass doors the architect had taken down for the occasion, most of the 1929 photographs bring out the separation of functions between the flat roof—supported by two rows of fine vertical steel posts, cruciform in profile and set back—and the glass or marble partitions that seem to slide perpendicularly between the two parallel slabs of the base and the roof, creating cantilever effects that are partly illusory, while thecella (to the rear of which once stood the statue by Georg Kolbe) appears out of line, ajar, the way a drawer or a box of matches might be (an option that Mies systematically played with in his patio house projects of the 1930s). Meant to represent Germany itself, sitting alongside the exhibits of the country’s main industrial firms, the pavilion did not answer any well-defined purpose. As far as function goes, or its value as an exhibition or representation, it did not show anything and did not exhibit or present anything but itself, made as it was to be entered and traversed both physically and by sight. It was a place that promoted a kind of circulation that was even more visual than pedestrian, without anything to block one’s movement, save for the two famous Barcelona chairs, placed there in expectation of the inaugural visit of the royal couple and then left in place like an empty figure of absence or of a presence always deferred. The reconstruction today milks that figure for all it is worth, as Mies himself tried to do in the lobbies of the apartment buildings along Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive.

Beyond Kolbe’s sculpture, the two Barcelona chairs, and a few stools of the same design, the Barcelona Pavilion housed no other object or work of art. No display cabinets, no pedestals, no supports, no surfaces for hanging anything on, either; the marble, onyx, and glass of the walls, as well as the vertical panels that demarcated, divided, and articulated the site or, better still,marked it, ruled out the very idea of such things. Instead, the panels themselves, in their potentially sumptuous materiality, became the equivalent of paintings, stretching outrecto-verso to the dimensions, if not to the very density, of the wall or partition. Was that due to the ascendancy of the model constituted by the Barcelona Pavilion on paper, an ascendancy confirmed by the 1942 museum project for a small town in which the image ofGuernica played the role of a wall? I have never been able to look at the large-scale paintings of Jackson Pollock or Barnett Newman, or even certain canvases in Monet’sNymphéas series, without seeing in them the desire that haunts a certain kind of modern painting to replace the wall to the point of superseding any notion of hanging—I would even go so far as to say making the wall obsolete. Architecture, of course, is familiar with the opposite temptation, which sometimes dreams of opting out of the very determinations that define architecture in order to practice freely on the blank page.

11.2

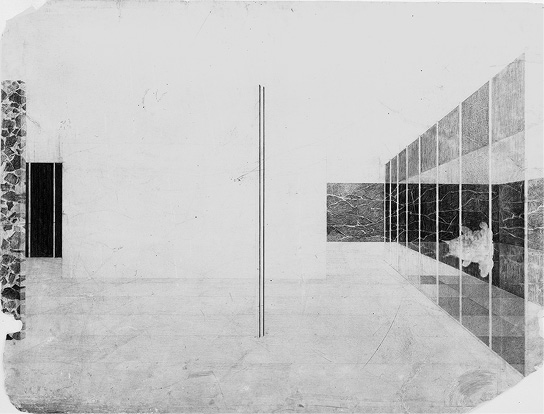

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, German Pavilion, International Exposition, Barcelona, 1929. Interior perspective. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Image © The Museum of Modern Art. Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

Mies made at least one graphic study for the interior of the Barcelona Pavilion that directly illustrates what I am saying. In that study, there is a thin vertical bar consisting of two parallel lines neatly drawn with a ruler and corresponding to one of the metal supports I mentioned. (Nothing here allows us to use the termcolumn, either in the look of the drawing or in the function of the support, which is deliberately blurred and even erased, as it is in reality in the building. If my thinking thus far makes any sense, it is in inciting the reader to measure precisely how much the discourse on Mies’s oeuvre would be altered, even transformed, if we made it a rule—at least provisionally and as an experiment—not to use the wordcolumn in its regard. A number of tirades about his alleged “classicism” would then certainly lose their raison d’être.) On either side of the bar and drawn along the axis of the page, without being able to be precisely located in depth but letting itself be glimpsed on the left, parallel to the outline of the inscription, there is the beginning of a speckled marble panel, behind which a fragment of a glass partition emerges, given rhythm by vertical mullions, while the right side is filled with a more complex device. Seen in perspective, that presents two marble panels set at a right angle, in front of which sits a tiny glass panel, identifiable as such by effects of transparency and reflection that are quite obviously calculated, even if something like a cloud seems to pass through, driven by some mysterious wind. It is as if architecture, concerned as it is with its own limits, intended here to compete with painting at a moment when painting attempts to escape its own identity—something it could only succeed in doing by borrowing painting’s tools, including those of collage (as in the concert hall project of 1943), but not without the constraint of the plan still asserting itself more strictly than ever.

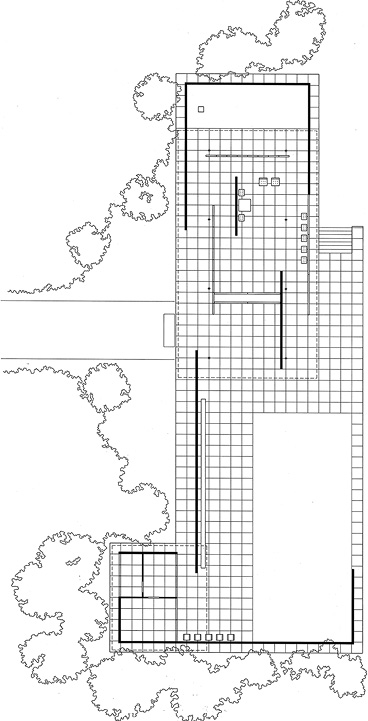

The constraint of the plan: criticism has always fallen into the trap denounced by Le Corbusier, a trap set every time the plan (in the architectural sense of the term) is supposed to be taken as the generator of the surface and the volume, so that all that can be seen is a network of signs that act like a mosaic, a decorative panel, in the two dimensions of the plane (in the geometric sense of the word).3 The same illusion led Alfred Barr to make a connection between Mies’s Brick Country House project and Theo van Doesburg’s 1918 painting,Rhythm of a Russian Dance, based on analogies that could hardly be described as formal, in the strict sense of the term, being in the final analysis merely picturesque. As Peter Eisenman4 clearly saw, if van Doesburg’s work might have taught Mies anything, it would have been the extent to which Mies could have used it as an argument for radically subverting the figure-ground relationship that seems to be the basis of all perception and first and foremost any apprehension of a painting. But this trait only appears if we consider the plan of the country house or the plan of the Barcelona Pavilion as the projection on the ground of a device that can only be fully developed in the three dimensions of architecture. In Barcelona, every partition but also every opening—the solids and the voids—functions in turn as a background in relation to another partition, another opening—another solid, another void—in an endless exchange that mobilizes only “figures.”

In this context, the vertical supports correspond to so many marks, and even incisions, made on or in the void, in the immediate proximity of surfaces that do not themselves enclose any volume, caught as all of them are between the floor—that “horizontal wall,” as Le Corbusier defined it in terms introduced by Alberti—and that other kind ofwall that is the flat roof, laid on two rows of set-back posts. The same roof is drawn directly in the floor plan, in a twist that is revealing here, motivated as it is by the constructive system. If the architecture is no longer bound by the rule that governs walls, it is because it has shifted its impact onto the horizontal walls, where it lodges in the intervals, because the vertical elements do not seem to have the function of supporting so much as of manifesting openings and measuring gaps. The glass box of the Farnsworth House (the plan of which dates to 1946, though Mies built it in 1950) is built between two apparently identical slabs, one clearly detached from the ground and the other overlaying the first and doubling it at a distance marked by two rows of metal posts of the I-beam type. In the square-plan Fifty-Fifty House project, the four posts that hold up the roof (itself consisting of a square network of metal sections soldered onto a steel plate) are not laid at the corners but in the middle of each of the four sides of the square. Both projects bear witness to a similar separation between the structure, in the classical sense of the term, and the volume, which is marked by the essentially transparent surfaces.

11.3

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, German Pavilion, International Exposition, Barcelona, 1929. Floor plan. Drawn by the Mies van der Rohe Chicago office. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Image © The Museum of Modern Art. Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

Architecture is thus reduced to a paradoxical volumetric game in which the diaphanous space occupied by a transparent body, defined simply by its bones and by the effects of reflection produced at its surface, or by a body with falsely labyrinthine consonances, articulated by a set of vertical planes unevenly distributed between two horizontal slabs of variable area, interferes with an essentially linear constructive structure without ever merging with it. That game, based as it is on a repertoire of simple elements and an economy of means taken to the extreme, inevitably parallels the practice of the twentieth-century avant-gardes, whether the neoplasticist or constructivist avant-gardes of the 1920s or the minimalist or conceptual avant-gardes of the 1960s. The comparisons are, of course, misleading, but they should not be ignored, since it is on these kinds of similarities and anachronisms, and even blatant misinterpretations, that what we call the history of art, which includes architecture, is in reality only partly built. The retrospective glance we cast, through the lens of our own day, over the artworks of the past, however recent they may be, is no less relevant, in this regard, than the effort to understand their genesis in the terms of the times that saw them come into the world.

Just after World War I, Mies van der Rohe was directly involved in the experiment of the avant-gardes of Europe, first as a director of the architecture section of the Novembergrüppe, created in the middle of the revolutionary period, and a bit later, between 1922 and 1923, when he provided active support for the reviewG. Edited in Berlin by Hans Richter, Werner Gräff, and El Lissitsky,G published some of Mies’s reflections in the form of aphorisms on architecture, as well as several of his projects, starting with the Friedrichstrasse office blocks.G was short forGestaltung, as indicated by the publication’s subheading,Material zur elementaren Gestaltung: Gestaltung in the sense of an active, dynamic development, a shaping;Gestalt in the sense of an ordering, a configuration, potentially unstable, random, an organizing process that always has to be started over again and therefore is distinct from its static sense, which is inseparable from the idea of completion. The word could not help but resonate with the emphasis Mies persistently brought to bear on the act of constructing and the idea of construction. If it is anachronistic to try to deal with his work from the position of our contemporary discourse, the confusion might be less the fault of the critic or the historian than that of the period we live in, with its antitechnological bias and the lack of interest felt by a number of architects in problems that are strictly constructive; construction has ceased to be both the matrix and the regulator of architecture (but how long can this last?).

The adjectiveelementaren in the subheading counts as much as the wordGestaltung here, suggesting a kind of shaping that comes down to its elements, its principles, and is reduced to the essential or, better still, taken to the limit, to the threshold beyond which the concept of construction ceases, purely and simply, to develop. We are a long way, here, from any idea of skill, from any extravagance, from any technologicaldramatization. If the Barcelona Pavilion established itself as a model of technical perfection, worthy as such to represent Germany in the circumstances, this is first because of the clarity and precision of the assembly of the different elements involved in its construction, the cleanness of their bones as much as the beauty of the materials, the combination of precious marbles, carefully machined steel, and faultless glass panels. Things had developed by then from themisérabilisme cultivated by an entire section of the avant-garde, by Dada and constructivism, partly out of necessity, partly out of virtue, for some time after the end of the privations following World War I. In this respect, the prototype pavilion was actually more in tune with the “minimalism” of the 1960s, which more easily accommodated “high-tech” effects than the deliberately parodic and derisive elementarism of the 1920s. As for the technical improvements that were brought to the reconstruction, I cannot see how they would change the building’s impact today.

If the pavilion is (or was) a prototype, then the question, as I have hinted, is how its reconstruction may alter its meaning or impact, though this will no doubt have less to do with the historical than the theoretical order. The idea that a visually repetitive architecture, with which the name of Mies van der Rohe is associated, by definition lends itself toreproduction is commonplace—but experience has refuted the accompanying ideas of invariable types, the end of the unique object, theunicum in the series. For me, as a lover of architecture, my discovery in the early 1960s of the Seagram Building, the Lake Shore Drive apartments, and the buildings of the Illinois Institute of Technology was a revelation that nothing since has been able to shake. In spite of appearances, and with a few exceptions that I only discovered later, there was scarcely any relationship between what was revealed to me then and what had been presented to us in France and elsewhere as “modern” architecture, or even a mode of construction inspired by Mies’s example (I was then in the Paris of the building of the Maine-Montparnasse skyscraper, the reconstruction of the Seine waterfront, and, shortly after, the development of La Défense). If the difference was striking, the reason was unclear. I could, of course, see that it was not only a matter of planes, surfaces, and volumes, or of materials, lines, proportions, or technical perfection—even though all of these considerations had their importance. It took me a while to realize that, to the contrary, one had to privilege the objects over the series, or types, while taking very seriously the celebrated, but incredibly enigmatic, motto that Mies gave himself:less is more.

That, one might say, is a matter of economy, even when it comes to difference—in relation to which the so-called identical reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion easily looks like a parable. Now reproduced, the model has lost its value as a monument and become nothing more than a double or doublet, one of a pair, a life-size maquette, something like the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion perhaps, reconstructed a long way from Paris on the outskirts of Boulogne, or, if the project goes ahead, Melnikov’s pavilion among the “follies” of La Villette: curios at worst; museum pieces at best (and are things any different—and in what context!—with the restored Villa Savoye?). The parable (which means comparison,parabola) shows us that despite its repetitive appearances, Mies’s work does not lend itself to reproduction, in the strict sense of the term, and that if there is a series there, then its generative principle is to be found not in repetition or some recurring typology but in the patient, obstinate, methodical search for the minimal deviation, the minimum perceptible difference between two individuals that all the signs suggest merge, and in which precisely lies the difference eliminated by reproduction. But that would still count for little if the difference were reduced to a simple variation. Difference, in Mies, was the object of real labor, prompted by an intention, if not a concerted calculation. It fabricated astory, a story that was exclusively architectural, so that we are entitled to speak of the labor of the work—the very labor of which the reconstructed Barcelona Pavilion is today like the recovered emblem, the recaptured trophy.

The labor of the work is thus easily confused with that of the difference; the architecture is no longer thought of as being of the order of the supplement (the decor) or of value added to the building (did New York City not try to tax the Seagram Building for its architectural quality, that which indeed made all the difference?) but as a kind of passage to the limit, in the serial process, to the experience that is, so to speak, liminal, bearing as it does on the differential thresholds between “less” and “more.”

I will mention here just two examples that are in fact complementary. The first was supposed to lead gradually, via the suite of buildings on the IIT campus, to the elimination of the element that I hereby refuse to describe as a “column.” Crown Hall, the home of the College of Architecture, may well follow its predecessors, as inserted in the volumetrics of the overall project, but it derives from a kind of architecture that, if not suspended, is at leasten suspension, or hanging, a goal Mies never stopped pursuing his whole career, beginning as early as the late 1920s in the Mannheim theater project with its reticulated slabs, supported by set-back supports made redundant by the external porticos. In both cases, the technical apparatus, which I would describe as the “grid,” is transferred from the vertical surfaces to the horizontal surfaces, as in the spectacular demonstration of this procedure at the National Gallery in Berlin.

That transfer leads to the second example of work on the “slightest difference” that I want to invoke here, which concerns the relationship between solids and voids. Le Corbusier was distressed at seeing holes that pierced a wall, “holes that are passages for man or for light: doors and windows,” that destroy the form instead of accentuating it: hence the idea of resorting to grids or checkerboards on surfaces.5 Here, too, Mies’s work on the grids of his facades, from one project to the next ordered by the interplay of calculated differences, paradoxically makes perfect sense in relation to the model proposed by the Barcelona Pavilion—an architectural device in which no wall is pierced by holes, where the passage of bodies and light is reduced to a play of intervals and transparencies.

In the days ofL’Esprit Nouveau, Le Corbusier saw the factories of America as the “reassuring first fruits of the new age,”6 an era that Mies, as a close reader of Max Weber, would have been more tempted to identify with the triumph of bureaucracy. However, it would be making a groundless accusation against him to characterize his architecture as “bureaucratic.” The Seagram Building, which differs markedly from the early proposals for Friedrichstrasse in 1921–1922 and again in 1933 for the Berlin headquarters of the Reichsbank, takes its place in a different series, inaugurated by the low-rise tower blocks on Lake Shore Drive and continued in Toronto, and is entirely “other” from that of the commercial office buildings of the Chicago that received Mies in 1938.

The same “monuments” that are the products of the forces and technological instruments used by Mies and developed to his advantage tend, with distance, to lose their burden of reality and to operate in the hallucinatory mode of paper architecture. The reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion will be justified when the Catalan capital becomes one of the obligatory stops on a pilgrimage that starts in Berlin and leads, via New York, to Chicago, justified for all those who do not confuse history with the cult of relics or ruins, who are not easily taken in and can claim to have seen with their own eyes, touched, and explored the monuments of a modernity captured at the very real moment of its difference.

12.1

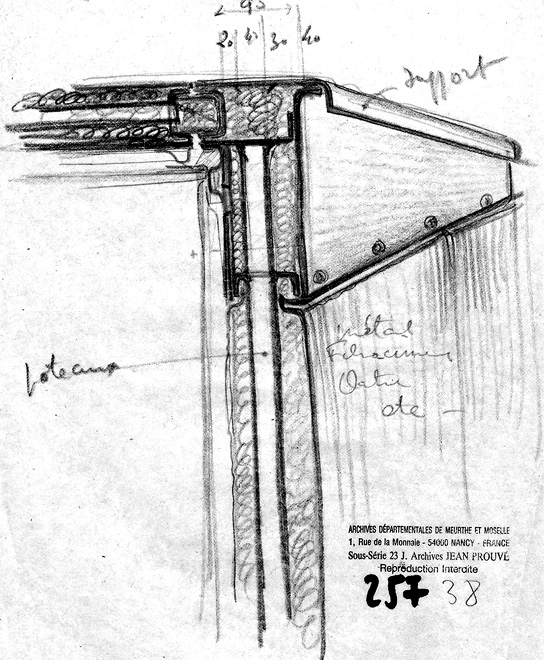

Ateliers Jean Prouvé, sketches for l’Unité d’habitation, Marseille, Le Corbusier, architect, 1946. Fonds des Ateliers Jean Prouvé. Archives départementale de Meurthe-et-Moselle. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.