13 Architecture Is . . .

The Undecidable

Looking at the range of issues debated in the architectural press today, one would be tempted to claim that everything seems to be relevant for the architect. Since Alberti, the curriculum traditionally assigned to the architectural apprentice has amounted to the same range and diversity as the training required today for becoming a psychoanalyst: The architect has had to be versed in all matters, in mathematics as well as in the humanities, in history and mythology as well as in economics and technology, and be able to design, to speculate, and even occasionally to philosophize. Time has passed without making things any easier for the architect. My reference to psychoanalysis is just a way of pointing to what Rem Koolhaas calls the “hazardous mixture of omnipotence and impotence” that architects are currently experiencing when they deal with problems that preclude, on their part, any form of conscious mastery. As Rem used to say, the architect is entitled to the unconscious.

Let us start by playing, in a philosophical mode, with the wordanything, which was chosen to conclude the Any series of conferences. If architecture is “anything,” or if anything deserves or, more neutrally (fordeserving introduces an idea of value, or evaluation), if anything is to be labeled as “architecture,” then what is it? Architecture as (a) thing; the “architectural” thing; the thing “architecture”: as has been the case in other Any conferences, we seem to be confronted with multidisciplinary approaches that tend to pull apart the object under scrutiny. InAnybody, Cynthia Davidson refers to the body as being dismembered in the process and being if not destroyed, then at least dissected. “Anything” sounds different, for the invocation of the “thing” points toward some sort of unity, regardless of the prefixany. As Heidegger put it, in everyday life we do not encounter the “thing” as such, only the individual things that surround us. In terms of architecture, things are buildings and/or images, projects, plans, models of buildings, anything that is commonly held to belong to the realm of architecture, whatever that means. This leaves us free to extract—or to “abstract”—from such a multiplicity a general idea of this art and its whereabouts.

Of course, this involves operating from a totally different perspective than Heidegger, whose questioning inDie Frage nach dem Ding moves toward what he calls “thingness”: toward what turnsone thing intoa thing, the condition of its being a thing (“Was das Ding zum Ding be-dingt”). Nevertheless, we may benefit from some of his remarks. First,das Ding, the thing—in French,la chose, from the Latincausa—commonly refers to an affair, a process in the judiciary sense; a matter of debate, an issue that calls for the judicial faculty, a “case” to be studied and solved. Second, beyond the world of everyday experience, things belong to different varieties of truth—or, to use Wittgenstein’s term, things present themselves under various aspects. To paraphrase Heidegger, the sun is not one and the same thing for the peasant and for the astrophysicist; the body is not one and the same thing for the dancer or the biologist. In the same way, a house is not one and the same thing for the contractor who builds it and for the client who inhabits it, not to mention the diverse components, the various aspects of the “case,” that the architect who designed it may have been playing with. Being a thing means precisely this: that one and the same thing allows for diverse (and eventually mutually exclusive) varieties of truth.

At first glance, it seems that one way of addressing the issue of what architecture is, or is supposed to be, would be to explore what it is not, or is not supposed to be. Such a move would lead us back to the issue of specificity, which Rosalind Krauss raises inAnymore. Strangely, dealing with architecture as a “thing,” the “architectural” thing, the thing “architecture,” not only means differentiating between what it is and what it is not (architecture being defined as “anything but . . .”); it also, at a deeper level, implies reconsidering the very relationship between what architecture is, or is supposed to be, and what it is not, or is not supposed to be. If, as far as architecture is concerned, there seems to be no room for “anything but . . . ,” then this is due not only to the range of issues that are of relevance for the architect, in terms of both practice and theory. Historically speaking, the “specificity” of architecture has always been challenged by the need for the art to confront demands that were by no means “artistic.” More fundamentally, one has to recognize in architecture’s present willingness to cope with what seems to be most foreign to it—time, movement, instability, shapelessness, and so on—a characteristic of its condition at the end of the millennium. Hence “undecidability,” a keyword of the Any series and a concept that may seem contrary to the idea of specificity.

I would briefly like to test this keyword ofundecidability in terms of dimensions, both temporal and spatial. From Koolhaas, we learn to stop thinking of architecture as being part of some quasi-utopian “things to come,” the way the modernists did. Rather, his exploring the Pearl River Delta or flying over Lagos is revealed as a way of measuring what is actually going on and how far things may have gotten out of control, in the traditional and most problematic sense of the word. It would be too easy, and overtly repressive, to decide that such developments are anything but architectural. Nonetheless, they certainly challenge the commonplace view of architecture as planning or building for the future. The new modes of producing architecture force us to reconsider to what extent, and no matter what purpose or lack of purpose, the notion—the stage of the “project”—is inherent to architecture, whether built or not. (Similarly, new architectural mediums, new tools, and new machineries of conception force us to reconsider the related concept of “projection.”)

“Paper architecture” has been an integral aspect of architecture since the period ofperspectiva artificialis provided a valid model and tool for both the art of building and that of painting. Geometric projection was used in both arts not only to represent objects or buildings as they appeared or were to be seen but also to conceive or, according to the terminology of the period, to invent or to compose them. This technique was used first to construct the scene (the grid, the checkerboard) on which the invention, the composition, and eventually theistoria that for Alberti represented the supreme goal of painting was to take place, including its architectural setting. It took several centuries before the painter was no longer satisfied, metaphorically speaking, with throwing ideas against the wall, as an architect might do on paper, and began, nonmetaphorically, to project paint directly on to the canvas, the only intermediary being the gap between the hand and the surface. But to what extent does the wordprojection apply to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings? The question is relevant to architecture insofar as it suggests a radical transformation of the idea of projection, rather than the concomitant notion of the project as such. It implies that the interval between the project and its realization strictly corresponds to the distance induced by the mode of projection itself—allowing or not for the possibility of a critical distance, or distanciation, specific to architecture (at least to paper architecture), if not to painting.

The problem is that the corporate museum architecture of the 1950s—the “white cube,” as Brian O’Doherty has labeled it—provided the perfect setting for Pollock’s drip paintings, as well as for Barnett Newman’s antithetic attempts toward the sublime, Jean Dubuffet’s explorations into theinforme, or formless, and, later, for Frank Stella’s and Ellsworth Kelly’s alternate geometries. It was as if its own form of strictly repetitive, quasi-mechanical abstraction would itself accommodate different types or modes of painterly abstraction, be they based on automatism, meditation, calculus, or a combination of all three. This may seem to be a simple play on words, but what is at stake is the very idea of abstraction, the matter being one of comparison: In what terms, at what level, from what point of view, and playing in how many dimensions are we going to tackle the issue of abstraction in architecture or in painting? In stylistic terms, what would allow for an approach both formal and historical, in which abstraction would be considered a period style characteristic of the twentieth century (given that the century is now over)? Or are we to deal with abstraction in generative terms—with abstraction as a process that is independent of any particular stylistic manifestation, a process that is intrinsic and, in different ways, foundational to any form of art, be it labeled representational or nonmimetical, figurative or constructive?

Fifteen years ago, Gillian Naylor tackled this issue in a particularly instructive article, the title of which is itself problematic, because it refers to a specific moment in the history of modernism—the foundation of the De Stijl movement after World War I—and to Theo van Doesburg’s attempts to demonstrate architectonic ideas that were in accordance with the twentieth-century artists’ “grand vision of placing manwithin the painting instead of in front of it.”1 In asking “abstractionor architecture?” Naylor questions whether the harmonies and values of painting could be translated without compromise into three-dimensional form. The question may sound odd, for we spontaneously (and in many ways mistakenly) think of architecture as an abstract art in its very essence, just as we do of music. Nonetheless, the matter was of real consequence at a decisive moment in the rise of what was to be called “abstract art.” The debate among the founding members of De Stijl resulted in a schism between the artists (painters and sculptors) on the one hand and the architects on the other. Meanwhile, van Doesburg aimed desperately at realizing in material form what he believed the other arts had already achieved in an imaginary manner. Material form was understood as three-dimensional space, whereas modern painting was supposed to have reduced corporeality to flatness—that is, to the two dimensions of the plane or the surface. What matters here is the assumption that painting, at that time considered “the most advanced form of art,” had by then paved the way for modern architecture. Conversely, a useful approach to the relevance or nonrelevance, the working (or nonworking) value of the idea of abstraction today, would be to consider how and in what ways abstraction operates in the field of architecture at a time when painting has ceased to be the trailblazing medium it was in the first decades of the twentieth century.

According to Naylor, it was easy for van Doesburg to demonstrate architectonic ideas that incorporated all of the qualities De Stijl artists attributed to painting, because most of his projects remained in model form—that is, on paper. However, the twentieth century did not usher in the ability to conceive the relationship between architecture and painting in transformative terms. Five centuries earlier, Alberti’s approach to the problem of ornament was already entirely dependent upon the passage, or shift, from the two-dimensional space in which the painter operated, in terms ofcomposition, to the three-dimensional space the architect dealt with and in whichconstruction was to take place. We know of Alberti’s definition of the column as “the first ornament of architecture”2—a definition in line with Bertold Brecht’s famous proclamation that the proletarians were entitled to the column and had the right to enjoy it in their dwellings. However, how are we to understand Alberti’s statement that he borrowed this ornament from the painter, together with architraves, bases, capitals, pediments, and other such things, as found in his treatise on painting, written some twenty years before his text on architecture?3 How could painting serve as a reservoir of forms for architecture unless we think of these forms in terms of “ornament”—that is, in bidimensional terms?

The wordcomposition does not appear in Alberti’sDe re aedificatoria, but inDe pictura it corresponds to the second part of painting, immediately followingcirconscriptio: once the painter has delineated the surfaces, a figure is “composed,” in projective terms, then it is time for him to assemble or “compose” these elements on the picture plane as in a puzzle or a work of marquetry. In the same way, according to Alberti, the process of writing supposes first the tracing of letters and second their combination into words on a sheet of paper.Compositio thus relates to projection—that is, to the two dimensions of the projective plane. Significantly, inDe re aedificatoria, when Alberti begins to deal with the different orders of columns, he directly refers to the same paradigm of writing. Starting with the capital, which identifies it as part of the “order” to which it belongs, the column is described as a succession of profiles that assume the shape, when projected on the plane, of different letters: anL, followed by anS, anI, and so on. The column as ornament is thus reduced, projectively speaking, to a succession of elements that are assembled on the plane in the same way as letters on a page. To put it in Derridean terms, ornament, considered in its linearity and bidimensionality, is supposed to be supplemental to architecture in the same way that writing is supposed to be supplemental to speech. It was asornament that the architect borrowed architraves, capitals, bases, columns, and pediments from the painter, thereby adding value to his art.

As far as composition is concerned, architecture therefore had to operate in the two dimensions of the plane. One may find it astonishing that Alberti, of all people, made no room for perspective inDe re aedificatoria, even though he offered the first systematic exposition, inDella pittura, of the method by which it became possible to represent building as it appears in three-dimensional space. According to Alberti, architecture first had to settle within the two dimensions of the plane and to “compose” with painting in order to develop its own distinctive mode of representation—one that excluded any illusion of depth or distortion of volume that could alter the sense of proportion. It is remarkable that in the twentieth century, under pressure from painting (then considered the dominant medium), modern architecture still faced the same challenge, yet with a radical reversal of the problematics of ornament. The same Adolf Loos who held that “ornament is crime” found no better way to eliminate or repress it than to systematically apply an abstract and planar facing or coating over the built structure; whereas the members of De Stijl were still dependent, in “composing,” upon the interplay between vertical and horizontal planes, conceived, according to Bart van der Leck’s definition, as “the delimitation of light and space.”

Given that I have been considering the thing “architecture” retrospectively, one might ask: How does this relate to the present? If architecture is something more than a productive agency (for example, a way of thought), then how are we to deal with the models it is actually working on? Pierre Rosenstiehl, a French mathematician and friend of mine who specializes intaxiplanie—that is, the study of the nature and properties of different varieties of planes—makes a very simple demonstration of the kinds of problems we are confronting today at the juncture of diverse disciplines, diverse ways of thought, and one that incidentally also points toward a new alliance between mathematics and the arts: Imagine a piece of paper. It presents itself as a two-dimensional sheet. If I crumple it, I get a kind of sphere or ball that is three-dimensional in volume. If I then uncrumple it, I have something neither bidimensional nor tridimensional, but what we might call “planar.” (I could simply fold it; the result would be the same.) Planes should not be seen or considered as mere surfaces, reducible to two dimensions. Unlike surfaces, planes have a kind ofthickness, in that they allow for different modes of wrinkling, crumpling, folding and unfolding, overlapping, interweaving, and interknitting. These are all operations that architects are currently involved in, so we have to rely on their practice—even if it is strictly “virtual”—in order to learn how to think in topological terms. This calls for taking into account new and other mediums and technologies, new and other abstract procedures and machinery, which, to paraphrase Greg Lynn, present architecture with yet another possibility to both rethink and retool itself, just as it did with the advent of perspective and with projective and stereometric geometry.4

Space, time, architecture: the theoreticians of the modern movement were at pains to add a fourth dimension to the game of architecture. Suggesting that art be considered as a way of thought no longer operates exclusively in either the two dimensions of paper architecture or the three dimensions of the built environment, but in the in-between. At the same time, it dismisses the opposition between vertical and horizontal, which directly relates to the idea of undecidability that was fundamental to Any’s approach to architecture. It also induces a new approach to the notion of construction and to the ideas of form and formlessness, an issue that was debated at length in theAnybody volume. Can we still pretend that architecture is anything but formless, a mere matter of form, when it deliberately operates between form and formlessness and confronts theinforme at the risk of shapelessness itself being turned into aconstructum? A move is required that would correspond to the shift from architecture as setting the stage for history to architecture being practiced as a game that can be looked at under different conditions. (Consider, for example, Peter Eisenman’s use of the grid, no longer seen as a checkerboard or a support for any kind of board game but as an integral part of the game itself, whose variations, deformations, and transformations allow for its constant restructuring and redefining.)

I want to end with a question around not the idea of “anything but . . . ,” but the idea of “anything like . . .” Even if we were to follow Fredric Jameson in getting rid of the concept of the aesthetic and in accepting the idea of beauty as definitively outdated (something which I doubt; it may rather be a matter of displacement or relocation), then there would still be the incentive to see the distinction between, or simply the existence of, “good” and “bad” architecture. To put it more radically, there will still be the urge to decide whether anything exists that could be labeled “architecture” tout court. Where does architecture begin? And where does it end? Where, to what extent, and within what limits is architecture at play? The thing “architecture,” or the “case” of architecture, calls not only for study but also for critical evaluation and judgment, leaving room for debate (a debate concerning aesthetics, according to Wittgenstein) and for choices that correspond to specific moves.Undecidability was, indisputably, the right keyword for the project. What will come next is another story—maybe another thing.

Construction

Not unlike the previous Any conferences—occurring each year at the same time but always in a different location—this Anymore conference, located (as the prefixany demands) under the sign of a generalized epistemological wandering, is subjected in 1999 (the last year of the millennium) to a temporal horizon. Although taking place in Paris, it is also subject to an ideological and institutional horizon. An effort of accommodation imposes itself, accompanied by the invitation to deal with the absence or lack—a particularly sensitive matter in this building (Cinémathèque française), situated as it is under the invocation of the author ofEupalinos—not so much of an “architectural culture” as of a clear notion of what the conjunction of those two words,culture andarchitecture, connotes and what the implications of that conjunction are. What place does architecture occupy in what one might call the culture of our time? Under what species might one consider architecture as symptomatic of the state of that culture and its aims? If indeed there are aims, which would be architecture’s own? What relationship does culture, or whatever it is that now takes culture’s place, entertain in general vis-à-vis architecture? More profoundly, more secretly, what link, considered fundamental, can one discover between the very concept of culture and that of architecture?

13.1

Jean Dubuffet,Group of Four Trees, 1969–1972. Photo: Anna Robinson-Sweet. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

I will address my remarks to this last question. Allow me to introduce it via the detour of an anecdote that for me possesses the quality of a moral fable. In June 1982, during its annual convention that year in Honolulu, the American Institute of Architects awarded the painter Jean Dubuffet a medal accompanied by a certificate with the following inscription:

THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS

Is honored to confer this

AIA MEDAL

On JEAN DUBUFFET

Artist, sculptor, and iconoclast.

His works provide not only scale, focus, color and

texture but clear insights into the nature of the

architecture they complement—its space, volume,

structure and surface—blending architecture

and sculpture into a single entity.

Robert M. Lawrence, President5

Dubuffet did not make the trip to Honolulu to receive his medal. However, six months earlier, in a letter dated December 22, 1981, he thanked Robert Lawrence for the honor the AIA had conferred on him: “I am especially moved to receive from the Institute the award mentioned in your letter, and I am truly happy that American architects have chosen in this way to demonstrate the interest they have in my work. I do believe, it is true, that my work points in a direction that can inspire architecture to explore rich possibilities, possibilities where we would begin to see new structures from which symmetry, rectilinear elements, and right angles would be excluded.”6

The contradiction between the two discourses is patently obvious—that is, the contradiction between the words of the certificate conferred by the AIA (words that show every sign of having been carefully weighed) and those of the recipient, who takes exception to them in anticipation. The certificate makes implicit reference solely to the works—monumental sculptures of more or less huge dimensions—that well-known architects such as Gordon Bunshaft, I. M. Pei, and, more recently, Helmut Jahn commissioned from the artist. These were works that those architects expected (the text leaves no mystery about it) would reinforce the effects of the structures with which they were associated. Whereas in his letter of thanks, written before he could have been aware of the wording of the certificate, Dubuffet stands rather distant from seeing his contribution to architecture as something like a complement—or should one say supplement?—something that, far from affecting it in its form, on the contrary merely emphasizes its worth, reaffirms its message, and (the AIA would express gratitude to him for this) helps in understanding the nature of the work. Instead, it is precisely on the terrain of architecture—in the very domain of architecture itself—that Dubuffet comes to intervene, and in quite another direction and toward quite a different goal—as he had already done when he published his first “edifice” projects in 1968.

The entire affair is all the more edifying—the exact word—in that Dubuffet never made a secret of his feelings (likewise, never in the least mitigated) about the architecture said to be “modern.” Nor did he hide the disquiet he felt seeing an out-and-out modernist such as Bunshaft interested in his works to the point of collecting them—indeed, to the point of commissioning hisGroup of Four Trees, though you would have to say the work looks rather good at the foot of the vertical, rectilinear, glass tower that is the Chase Manhattan Bank of New York (as doesThe Tree Stand, adjacent to the cement snows courtesy of Marcel Breuer, at the ski resort of Flaines). In Paris, one might well think that Dubuffet’sTower of Figures is implanted on the Ile Saint-Germain at Issy-les-Moulineaux less in defiance than as a knowing wink of the eye on the edge of the contemporary metropolis—located in the immediate surroundings of what young architects regard as “the city on the periphery,” that strange urban ensemble that (in introducing itself into the interspace) has come to despoil the binary play of oppositions between the city and its suburbs. Analogously, theTower models the opposition between sculpture and architecture and imposes itself as a kind of interrogation of what can become of architecture when it has neither the rights to the city nor, for that matter, the right to be cited.

I have chosen Dubuffet to introduce my remarks less for his contribution, by itself resolutely peripheral, to the architecture of its time than for the attack he never ceased to press against the general culture and the control it exercises on the arts. When the time came for him actually toconstruct, necessity compelled him to borrow knowledge from the domain that partook of what can only be called a technical culture, hereinafter pushed to the point of academicism. In this sense, there is no art more “cultural” than architecture. In fact, Dubuffet was the first to recognize that human beings were irremediably situated in a culture and in particular could extricate themselves only partially—through art—from the cutoff from reality that language imposes. Let us begin, then, with regard to this concern, with the division that language imposes (at least in the West) between architecture and construction—a division that Dubuffet implicitly endorsed in his writings without really examining the matter more closely and without excluding, as one will see, all culture seen as “technical.”

What in fact does one read inProspectus under the title “Edifices”? That the sculptor of theTower of Figures was assisted in the interior design of the work by an architect, to whom we owe the general plans and the two models, the closest of which to the final configuration is namedLe Gastrovolve, in reference to the involuted character of an apparatus whose exterior aspect of perfect compactness leaves no doubt that it defers to the constructive norms of the most advanced modernism:

The construction of the edifice shall be based on the principle of hanging the entire exterior envelope on the arborescent interior apparatus of theGastrovolve, which, made as it is entirely out of concrete, will support the work. The floorboards will be cosmetic. The exterior envelope will be lightweight and thin, and simply attached in the manner of a curtain wall. It can also itself be made of concrete, but of small thickness, though preferably of stratified epoxy resin. In the latter case, a network of stiff materials, joining the meandering black tracings of the exterior decoration, can be used if needed—notably to strengthen the entire dome covering the highest room, which forms the cupola roof, of the building, etc.7

The moral fable, one might say, begins to take shape. The same Dubuffet who denied that the creation of art was the business of specialists did not hesitate to consult a professional when it came to erecting hisTower. This man, who could not find words strong enough to denounce architecture that he judged lacking,8 used techniques that were the very techniques of architecture itself. The moral that emerges from this story could take the form of a question: What does it signify for architecture that it is constructed and, perhaps even more significantly, that it isconstructed in such a particular manner? What do all these facts and practices signify, not only for architecture as a concept but also for architecture as a phenomenon of culture, through the prisms of which we can see something of culture’s own architecture?

On the concept of architecture, Jacques Derrida has opportunely reminded us that it is itself aconstructum, and whatever presents itself as an “architecture of architecture” has a history and is itself historical from one part to the next. This remains very much the case even if we accept that it is aconstructum that we inhabit, even as it inhabits us, and of a heritage that comprehends us even before we have made the effort to consider it.9 One might object to the notion that every concept, beginning with the concept of culture, is more or less constructed—if the remark did not have the effect of obliterating the relationship (apparently a sensible but highly problematic one when you think of its history) that the concept of architecture clearly maintains to that of construction: a relationship of difference as much as of similarity. In this sense, Derrida is right to say that “from its ancient beginnings, the most basic concept of architecture has been constructed.”10 However, why would one not add (and why did Derrida not add) that this concept had beenarchitectured, as is suggested by the lovely formula that insists that there is an “architecture of architecture?” It is not only because the verbarchitecturer—which entered the French language soon after the distinction was made between architects and engineers—has to be handled with caution, signifying (if I am to believe thePetit Robert dictionary) “construire avec rigueur.” Rather, the reason should be sought on a deeper level, somewhat approaching the heading “architectural culture”: architecture as a fact of culture, culture as inhabited by architecture as much as it inhabits architecture, culture informed by architecture as much as it informs architecture.

This philosophy attributes to architecture the idea of construction—together with all its additional resonances, including even Kant’s definition ofarchitectonics as “the art of systems”—but does not necessarily signify that all there is to architecture is construction. Nor does it allow one to suppose that the two are equivalent in the sense that the concept suggests—whether it is the concept of architecture or that of construction. Conversely, the image of God as the architect of the universe appeals beyond the idea of construction; the universe is not thought of purely in technical terms (in Kepler’s time, the mathematics applicable to architecture were at a very rudimentary stage and were almost entirely empirical), but also in aesthetic terms: regularity, symmetry, harmony, and even composition (harmony of the spheres, composition of forces, etc.), if not beauty itself. The dictionary distinction betweenconstruire andarchitecturer was justified by the rivalry that emerged in that constructive century par excellence, the nineteenth, between the professional groups heretofore constituted and which proclaimed for themselves disparate cultures: technology for the one, art for the other. However, it all went contrary to reason in that the diverse functionalisms insisted there was no “truth” in the matter of architecture other than a constructive one, at a time when the use of new materials, particularly iron and concrete, went hand in hand with the development of methods of calculation, in the literal sense of the word. Beyond its obvious tautology, the formulation that architecture is architectured also abandoned the idea that architecture is constructed. The question that concerns us here—that of “architectural culture” in its ideological as well as institutional aspects—is essentially tied to the difference, indeed to the conceptual split, that exists between the verbarchitecturer and the verbconstruire, betweenart andtechnique.

In his writings on cinema, Roland Barthes was not afraid to assert that the dream of every critic was to be able to define an art by its technique.11 This hope was paralleled by those linguists who laid claim to abstracting the condition of meaning so as to study language by its strictly technical, not to say constructive, aspects—in anticipation of recognizing an order that, in being presented as functional and therefore susceptible to entering into resonance with other morphological forms (mathematical, musical, etc.), can then take its place in the semantic order. One could say, a fortiori of architecture. Responding to this issue, I will allow myself to reproduce something I wrote more than twenty years ago as part of a research project, collectively undertaken, on the function of the sign in modern architecture; it was a period in France that was dominated by our readings of Manfredo Tafuri and the journalOppositions. I refer to a text that for obscure reasons was never circulated but that, despite being somewhat dated, still has relevance today:

To formulate in semiological terms the question of the relationship between architecture and construction, the notion (if not the illusion) of a functional order as a prerequisite to any semantization, from which every constitution or institution of sign would necessarily borrow, soon imposes itself. If architecture has the right to present itself as a language (though it does not see itself as “talking”), it is in the measure by which the form of expression that corresponds to the first instance of the operation of the semantization of functions models itself, directly or indirectly, on a supposedly coherent functional order. Each architectonic member is understood to maintain with the ensemble in which it insets itself, as well as with each of the other elements the latter is comprised of, a “reasoned” relationship (to revive Viollet-le-Duc’s expressionism). If architecture can seem to function as a language, it is because, to begin with, it presents the model of an arrangement, of a construction, of a structuration anterior, logically speaking, to the very operation of meaning. It is the model, one might say, of a double articulation, the masonry itself having to satisfy—in order simply to hold—a certain number of structural constraints, without which there would be no question of architecture, no more than one of language or, in parting, of culture.12

Architecture, then, is not simply a matter ofsupplement: a supplement of rigor (according to the dictionary), a supplement of meaning (with all the risks of failure we know these days), a supplement of beauty (architects are among the last people in the world not to be afraid of the word)—beauty that it could flatter itself to have discovered in construction, as the functionalist aesthetic would have it. Schelling’s definition of architecture as the “metaphor of construction” does not necessarily imply that the proper meaning of architecture, let alone its truth, is to be found in construction; note that Gothic architecture and its linear model of a constructive system possess in their details none of the rigor of the working drawing. However, a whole aspect of architecture also derives from the category of themask—and indeed the exterior envelope of Dubuffet’sTower acts as a mask, one whose figures deny in dissimulation the constructive apparatus of modernity. It is a design, let us say in passing, that itself represents a challenge to the traditional norms of construction, be it the suppression of supporting walls replaced by suspended panels, the out-of-line floor planks, or the truly revolutionary constructive role subsequently assigned to pressed glass and the like—in effect, all those things that are now part of the legacy, of the vulgate of architectural modernity. This, however, should not lead one to underestimate the work of deconstruction from which the vulgate derived. As Derrida insists, contrary to appearances, deconstruction is not an architectural metaphor:

The word should, the word will, name a kind of thinking about architecture, a kind of thinking about the work. To begin with, it is not a metaphor. One can no longer rely on the concept of metaphor. [This relates to Schelling’s formulation of architecture as a “metaphor” of construction.] Deconstruction, then, should deconstruct—to begin with and as its name indicates—the construction itself, the structural or constructivist motif, its patterns, its institutions, its concepts, its rhetoric. And deconstruct as well strictly architectural construction, the philosophical construction of the concept of architecture, the concept the model of which governs the idea of the system in philosophy as well as the theory, practice, and instruction of architecture.13

It is a matter, then, of culture and of thought—if such things exist. The architecture we callmodern did more than just instigate this project. It also precipitated a break with the principle of discontinuity, which construction had until then supported, by imposing new structural models in continuous veils—unthinkable until the invention of prestressed concrete—with the parallel demise of the distinction between the vertical and horizontal, upon which what Derrida called theject of the project (le “jet” du projet) had been grounded.14 This is to say nothing of the montage of elements—girders and crossbeams, which Viollet-le-Duc’s dictionary says nothing about, because they correspond to a level of structural articulation inferior to the formal and semantic units identified in theRaisonné (column, base, capital, arch, vault, etc.): the equivalents in language of what would be the level of articulation of phonemes in relation, semantically, to that of words.

Walter Benjamin did not fail to see in the precocious expression of architectural modernity that iron construction represented the first instance of the principle of montage—in a way that was neither metaphorical nor rhetorical, but strictly mechanical. “Never before,” one reads in the notes ofPassagen-Werk, “was the criterion of the ‘minimal’ so important. And that includes the minimal element of quantity: the ‘little’ and the ‘few.’ These are dimensions that were well established in technological and architectural construction long before literature made bold to adapt them.”15 Montage as a modality of construction took quite another turn with iron. Thus Marx, whom Benjamin quotes, writes: “It is only after considerable development of the science of mechanics, and accumulated practical experience, that the form of a machine becomes settled entirely in accordance with mechanical principles and emancipated from the traditional form of the tool that gave rise to it.” To which Benjamin adds, “In this sense, for example, the supports and the load, in architecture, are also ‘forms’”16

But the principle of montage does not correspond simply to a new modality of construction as much as it does to one of form, emancipated in theory from every kind of anthropomorphism and every kind of organicism. As its corollary, it appeals to the possibility of de-montage—not to be confused with deconstruction. Not that de-montage lacks theoretical, to say nothing of “deconstructive,” instances, which suggests that a building is an object obeying a transitory principle, but in fact it demonstrates that it was built to last. For example, a clause was inserted into the land concession act related to the construction of the Crystal Palace that stipulated the building’s demolition after the closing of the 1851 London Exposition (to the great consternation of the London public).17 More extreme examples were those buildings that lacked foundations, quickly erected in their locations, as in the manner of the houses of Jean Prouvé or even of a structure dropped onto the ground by helicopter, as with the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller. The fact that architecture has come to the point of even repudiating the idea of a foundation is something that we should not accept without consequence, especially in what passes for “architectural culture.” An architecture that will leave no trace of itself, not even ruins, spells a utopia that risks announcing itself to be as disastrous as its totalitarian antithesis. However, in an architecture that, without ignoring the preeminence of residential quarters, would instead of looking for some foundation rather expose them to every manner of variation and displacement, to every manner of transformation—an architecture of wandering, then, in its concept as in its realization—a thought, if not a culture, could find there a point of departure.18

Time

As far as space and time are concerned, Hegel has a way of classifying the arts that is paradoxical inasmuch as it is simultaneously generative and subtractive—generativity depending in this case on subtraction, and even proceeding from it. Architecture and sculpture come first in this classification because they take place and operate in the three dimensions of the objective world. Next comes painting, the concept of which implies the elimination of one dimension—that is, three minus one; painting develops itself up to the point of being converted into a pure magic of color that is nevertheless still of a spatial character, bound as it is to the two dimensions of the wall or the picture plane on which the interior self, the “subject” as we call it, projects itself in the guise of permanent configurations of forms and color. Last comes music, in its seemingly linear, one-dimensional, and ephemeral mode of manifestation—that is, three minus two; music, as Hegel writes in hisLessons on Aesthetics, does not proceed so much from the disappearance or subtraction of one more dimension of space than it does from the suppression of spatiality in general. The main task of music is to make manifest the most intimate self, the deepest subjectivity, the ideal soul, resounding, finding an echo, in the pure and permanently flowing element of time.

13.2

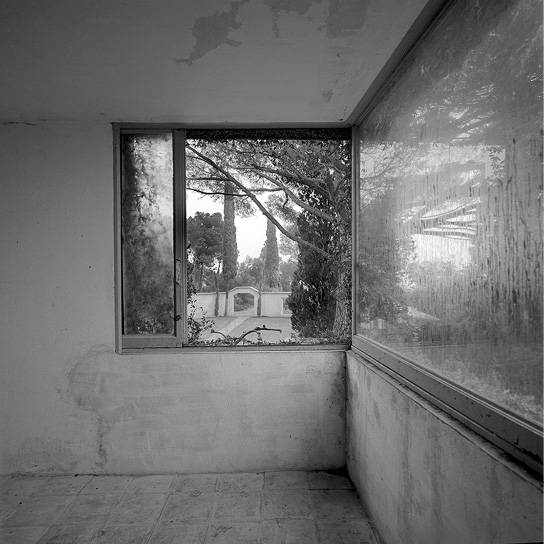

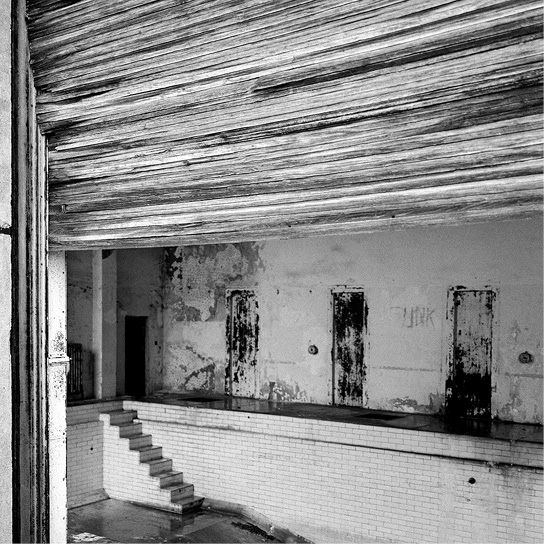

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

Architecture and music thus correspond to two opposite poles, traditionally referred to as the arts of space (architecture, sculpture, painting) and the arts of time (music and poetry). Far from assigning it the first rank in the hierarchy of the arts, Hegel considers architecture the most incomplete of all, claiming that it is unable to adequately express the spiritual through the use of materials concerned mostly with obeying the laws of gravity and therefore reduced to providing an external environment with only symbolic significance. Music, on the other hand, is thought to be the “romantic” art par excellence, because it deals with a material as insubstantial as sound—a material which, in turn, implies a double negation of exteriority; space is nullified by the way in which the body reacts to a mere vibration, which is thereby converted into a mode of expression of pure interiority.

13.3

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

13.4

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

The strictly conceptual opposition of space, as the element of exteriority and objectivity, and time or duration, as the element of interiority and subjectivity, is contradicted by the reality of movement. Movement is defined in terms of space and time, or perhaps it is space and time that are defined in terms of movement. Form in music is related to movement, just as movement is related to form. This calls for further investigations into the fabric of time, a fabric that, in spite of its alleged “linearity,” allows music to reflect itself in the mirror of form and structure and thereby recognize the spatial image of its development, its construction, and its architecture. But if, according to Friedrich Schelling’s famous metaphor, architecture is nothing but “frozen music” (eine erstarrte Musik), how are we to define music? As “defrosted architecture?”

In the story of Amphion as told by Paul Valéry (who used it as an argument for a “melodrama,” set to music by Arthur Honegger), a temple is built through the agency of music. Having received the lyre from Apollo, the mortal Amphion gives birth both to music and architecture when he begins to play it. The stones move and assemble themselves into a temple. Hence the challenge for the composer, who refrains from making use of all the resources of his art until they are developed in Valéry’s story of Amphion’s touch. The same is true for architecture, which at first was to be presented more as a simple exercise of movements and combinations than of structure or composition. In the same way that music retrospectively reflects itself in its own architecture, architecture projects itself in its own generative, not to say musical, process. But its relation to time and to its fabric goes deeper than a succession of choices and displacements, a mere succession of moves, as in a game or a play; it involves—or relies on—a kind of movement or dynamic inherent to its own fabric and which requires, in order to become visible, an approach other than metaphor, an approach that involves the medium of images according to their own movement, their own circulation, and their own dynamics.

13.5

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

Painting was for a long time associated with architecture. With the Renaissance, linear perspective became a common basis for both arts and provided architects and painters with an instrument that allowed them to commute freely between the actual three-dimensional space of architecture and the two-dimensional plane on which it was represented. This seemed to exclude any consideration of time or duration, except for the representation of ruins and decay or of the building process itself. The transformations that could take place within the frame of perspective all implied, in one way or another, a displacement that could be treated according to the same geometrical lines on which the comparison between architecture and music relied; any attempt to make room for the representation or expression of movement and its dynamics had to conform either to the rules of proportion or to the principles of harmony.

This state of affairs was radically altered by the discovery of photography and the invention of the cinematograph. According to Walter Benjamin, not only did photography change the very notion of art by replacing the question of photography as art with the notion of art as photography (that is to say, mechanically reproducible), it also called for a transformation of the whole Hegelian system of the arts. Benjamin, among others, noted that photography provided a better hold on an image, a work of art, and especially a building than could be obtained from dealing with the object itself. But this not only derives, as he thought, from the reductive aspect of photography and its greater mastery over a three-dimensional object (especially architecture) by the elimination of one dimension. What photography and, moreover, film reveal is that architecture cannot be considered only as an art of space; room has to be made, in its practice as well as in its concepts, for time and movement.

13.6

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

Hegel’s lessons left no room for photography and film. He was still free to consider architecture and music as the two opposite poles of art: one static, related to the laws of gravity as they operate in space, and the other dynamic, corresponding to the movement of sounds as they take place in time. Painting, as it eventually developed into a magic of color, emancipated itself from the reign of matter only to enter the field of appearances. As far as movement was concerned (and, according to Aby Warburg, it was of great concern to Renaissance art), painting succeeded in evoking, representing, or “expressing” it in a more or less illusionistic way but did not succeed in actually producing, or even “imitating,” it. For movement, as Gilles Deleuze later put it, not only takes place in space, as something that occurs between objects; it also expresses duration, in the Bergsonian sense, as something that, in opposition to time, cannot be divided into parts. The same applies to music, the movements of which actually take place in measurable, divisible time in such a way that one can deal with it in terms of composition, of structure, of architecture. However, the movement of sounds—theirtempo, even their color, and most of all, their rhythm, as they echo, according to Hegel, the rhythms of the heart and the soul—are more amatter of duration than of time: a matter of duration as Henri Bergson describes inMatter and Memory.

The discovery of photography dramatically altered the classification system of the arts. For photography, from the very beginning, has been related to both space and time. It relates to space as the element in which the project is actually taking place, and that allows for the reduction of the “view,” the object, or the model to the two dimensions of the photographic image. It is related to time as well, as the inescapable condition for imprinting the image on the sensitized plate or paper. It is related to time but not to duration, because the time of exposure implies the elimination of movement (“Stand still!”“Ne bougez plus!”). The subsequent development that led to the “snapshot,” or theinstantané, allowed photography to deal with movement, but only by fixing it, having it “frozen.” For a long time, photography was thus torn between two poles of attraction: on the one hand, the analysis of movement as it could be caught and represented through a succession of snapshots, and on the other, the image of stability. Here, of course, the paragon was architecture, which resists the ravages of time and surpasses the living model or still life in its ability to stand still in front of the camera.

The arrival of film disposed of the alleged opposition between the arts of space and the arts of time on which the traditional classification of the arts had relied. A new turn was given to the notion of “projection,” which, since the Renaissance, had been a component of the arts ofdisegno—architecture, sculpture, and painting. Projection was no longer considered merely a geometric process related to the two dimensions of the plane but a dynamic one involving a third dimension—the dimension of time—inseparable from the mechanism of the camera and the running of the film. With regard to architecture, the move was of great consequence, for the cinematographic approach meant dealing with architecture in terms not only of time but also of movement and, through it, of duration.

In his 1932 lecture, “The Story of Amphion,” Valéry referred to duration as the equivalent of memory and the equivalent of form: “duration, that is to say memory, that is to say form.”19 If when listening to music we supposedly have to memorize its developments in order to “understand” it, in the same way that we supposedly have to memorize the first words of a sentence in order for it to make sense in our mind when completed, it doesn’t mean that musical form is to be thought of in terms of space, as something we can only access in retrospect. Projection plays its role in the process, in a dynamic and prospective way; form is present, form is perceived, form is at work, on the move, for the listener, from the very beginning of the execution of a sonata as well as for the uttering of a sentence.

But what about architecture? What are we to learn about it from or through photography? What are we to learn about it from or through film? And no less important, does film outdate photography, make it irrelevant, with regard to architecture? I recently raised this issue in a short book that I worked on with the French photographer Jacqueline Salmon, about Robert Mallet-Stevens’s Villa Noailles in Hyères, one of the incunabula of modern architecture. The issue was all the more relevant in that Mallet-Stevens himself first worked as a set designer for the film industry (he designed, along with Fernand Leger, the sets for Marcel L’Herbier’sL’inhumaine, a film that was conceived and received as a manifesto in support of modern architecture). The tension between film and architecture was also at stake in a film on the villa that was commissioned from Man Ray by the Noailles in 1928,Les Mysteres du chateau du dé (The mysteries of the castle of dice).

13.7

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

In looking at Salmon’s photographs and at Man Ray’s film, one must be attentive not only to day passing into night, as reflected in the photographs, but also to the analogies and the differences between the two approaches to the building, analogies and differences that culminate in Man Ray’s rhetorical figures of movement (Man Ray being, first of all, the great photographer we all know). His film starts with a wide-angle, 360-degree pan of the terrace, with its openings on the outside, and then ignores the Mediterranean landscape (just as Salmon will, seventy years later) to shuffle into the house, through its corridors, staircases, and tunnels, and raise the eye toward the stained-glass grid that corresponds to the sky of the great salon. Here, the handheld camera slowly slides over the metallic grids on which the collection of paintings was stored and, turning upside down, finally ends up back on the terrace. It is a dramatic circular move that echoes the pan of the terrace and also turns the building upside down. I find it to be a good introduction to the notion of “defrosted architecture” inspired by Schelling and to the relations between architecture and what I called the fabric of time, its texture, and, by the same token, its relation to space. It is a good introduction to the way in which architecture addresses the eye and the body through the movement of the camera, just as music addresses the ear and the body through the movement of sound.

13.8

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Noailles at Hyères, France, 1923–1925. Photo © Jacqueline Salmon, 1996.

History

Ours is a time that seems to have no way of dealing with history other than as strictly retrospective, in the past tense. A time that doesn’t want to know of any form of ideology other than the laissez-faire, the mere and mechanical submission to the rules of the “market.” A time that leaves no room for utopias other than the degenerate, as in Disneyland. A time that precludes any projection into the future, unless evolutionary, in terms of profit, fiction (so-called science fiction), or fantasy, in the guise of identity or of virtuality, which in some way is the same (there is no identity but virtual, no virtuality but “identitarian” [identitaire], both in trompe l’oeil). My thesis is that no matter the conditions, architecture indicates the new paths (or nonpaths), the new ways (or nonways) that are or could be—I dare not say “or should be”—the ones of history (or nonhistory) today. Architecture also indicates the margin of “play” (in the sense of play in a machine or gear) that is left, beyond irony, for any form of creative, critical, or subversive activity.

1

Is there any way for a building, public or private, large or modest, to be declared “historic” or a “landmark” without reference to the past or to “style?” Is there any way for architecture to deal with “history” in its very process or activity, as well as in its appearance, in terms of structure or form? One of the most common criticisms of modernist architecture is that it had no concern for history. Indeed, the ideology of modernity implied a rupture with the past, under the labels of newness or rationality or both. As Walter Gropius once said: “Modern architecture is not a new branch added to an old tree, but a new growth, that sprouts directly from the roots.”20 The architecture of the “moderns” involved a projection into the future, the very notion of “project” being related to the forthcoming dimension of time, to the opening of things to come, things to conceive and construct, things to “plan” and to “project,” eventually to the detriment of the remnants of the past: project and utopia hand in hand, as Manfredo Tafuri recognized.21 For the constructivists, history had to do with expectations rather than with memories; with looking forward rather than with looking back; with construction rather than with conservation.

Architecture is not only a product of history, a product to be studied, analyzed, and criticized in relation to its context, conditions of appearance, or possibility. Architecture is an essential thread in the fabric of history, most especially in the fabric of “context.” It is an agent, or tool, in the making of history, in the development of new forms not only of dwelling but of production and sociability, of power and exploitation: new modes of historicity. This may sound like mere commonplace, but it needs constantly to be reassessed. The very activity of building, of projecting, is by definition future oriented. Even the great monuments that celebrate the past are a way of getting rid of it. Adolf Loos claimed that the tomb is the epitome of architecture: It is, first, a way for the living to come to terms with the dead, a way for people to come to terms with death itself. This is part of history and part of architecture, but only one part of it.

No one has better formulated this issue in contemporary architecture than Fredric Jameson—the same Fredric Jameson who, in a daring move, shifted gears from “postmodern” to “postcontemporary,” as if even contemporaneity, such as we have to live it, think it, be part of it, is already and irremediably lost as such; as if we could live it, think it, be part of it only in retrospect; as if history, be it contemporary history, history in the present tense, had from the start to be narrated in the past tense while failing to attain any form of coherence. Peter Eisenman’s project for the University Art Museum in Long Beach, California, is perfectly in tune with such a scheme, taking its form from—to quote Eisenman—“the overlapping registration of several maps” corresponding to various time zones, the coordinates of which are incompatible: “Beginning with the settlement of California in 1849, the creation of the campus in 1949, and the projected ‘rediscovery’ of the museum in the year 2049. The idea was to imagine the site in the year 2049, 100 years after the founding of the university and 200 years after the period of the gold rush.”22 Projecting into the future equates with reducing the future to its own archeology, with making up for the lack of deeper layers of time, the lack of “history” in the past tense that is supposed to be characteristic of America.

I quote, somewhat freely, from Jameson’sThe Seeds of Time:

Now the new individual building does not even have a fabric in which to “fit,” like some well-chosen word . . . rather (consistent with the freedom of the market itself) it must replicate the chaos and the turbulences all around it. . . . Replication means the depoliticization of the former modern, the consent to corporate power and its grants and contracts, the reduction of social conscience to manageable, practical, pragmatic limits; the Utopian becomes unmentionable, along with socialism and unbalanced budgets. Clearly also, on any materialist view, the way the building form falls out is of enormous significance; in particular the proportion of individual houses to office buildings, the possibility or not of urban ensembles, the rate of commissions for public buildings such as opera houses or museums (often recontained within those reservation spaces of private or public universities, which are among the most signal sources of high class contemporary patronage), and not least the chance to design apartment buildings or public housing.23

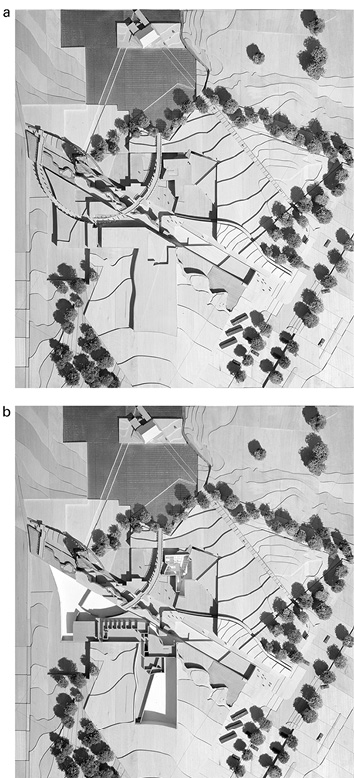

13.9a, b

Eisenman/Robertson Architects, University Art Museum, California State University at Long Beach. Presentation model for phase 4, with (a) and without (b) roof, 1986. Courtesy Eisenman Architects.

From the small private house rebuilt by Frank Gehry to what Jameson calls “the grandiose new totalities” of Rem Koolhaas, the contemporary (or shall we say the postcontemporary?) praxis of architecture demonstrates the narrow range of possible interventions left to architects in a world in which any form of planning has been subverted by building regulations and zoning laws that are applied in a strictly defensive and negative way; at the public level, the process of decision is reduced, at its best, to a choice between different moves that mechanically follow the weakest lines of resistance. The paths of “history” are such that today there seems to be only one creative way of dealing with this: to accept the constraints and to try to take advantage of them in order to develop new ideas. (As Koolhaas likes to say, in a Goethean way, with respect to New York City zoning laws: “The more you stick to the rules, the more freedoms you have.” Themore freedoms, in the plural.)

2

Among the types of public buildings that are publicly or privately commissioned today, Jameson mentions opera houses and museums—that is, buildings explicitly related to the issue of history or “heritage.” Strangely enough, he omits airport terminals, yet these are among the most important public commissions today, and they may eventually be turned in the future into museums, as train stations already have been (think of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris; in Washington, DC, a former department store is being turned into an opera house). For the moment, the museum is desperately attempting to resemble a terminal, with its halls, counters, escalators, zones of gathering, security booths, shops, parking lots, and herds of tourists that make us believe that museums are enjoying a vogue that equals one of the great pilgrimages of the past, even though the number of visitors they attract is in fact constantly declining.

The museum as a terminal, inside or outside the city: Not very far from here, set in the park of Upper Veluwe, is the Kröller-Müller Museum, a good example of the museum as part (in Jameson’s terms) of a reservation space. Here in Rotterdam, when the city council agreed, in 1928, that a new museum was needed, it seemed logical that the plan for the building retain the parklike character of the same site on which the museum of architecture, the Netherlands Architecture Institute, stands today: “A tranquil stretch of land in the midst of the city’s hustle and bustle.”24 Similarly, the Museum of Modern Art in New York has for a long time been conceived as a public oasis, an island of culture in the center of the metropolis. In fact, the architects who recently participated in the competition to remodel the museum were asked to treat it as a “campus”—that is, as a reservation space under high-class patronage.

The great collections that historically have been developed into museums were by no means restricted to a retrospective view of artistic production and to the celebration of antiquity or the great schools and periods of the past. When Vélazquez was commissioned in 1629 to go to Italy to buy works of art for King Philip IV of Spain, he mostly acquired paintings by his contemporaries or immediate predecessors. The first museums were not conceived as monuments of the past and still less as tombs or funerary sites, but rather as repositories of models for living artists. Things changed when, in the eighteenth century, the erudite sense of history and archeology overrode the concern for the present and when, partly due to the success of the salons, the art of the past and the art of the present were sharply divided, while at the same time the institution as such pleaded for continuity, often to the detriment of living art.

A symptom of the way in which we now deal with history is evident in the same split between the art of the past and the art of the present that gave way to the creation of museums of modern art, a split now reverberating inside those relatively new institutions as a split between modern and contemporary (and postcontemporary) art. The best way to avoid the apparent contradiction between the diverse approaches to history seems to be to dodge it by carefully isolating each layer of time in its own container, thereby avoiding or preventing any form of communication, exchange, or contamination among them. The museum has become some sort of air terminal, but in opposition to the imaginary one, or to what I would call the “paper museum”—in the sense in which we speak of “paper architecture”—it doesn’t offer flights to all destinations.

In 1979, referring to Cesar Pelli’s model for the new Museum Tower, Bill Rubin (then director of the Museum of Modern Art) declared: “This new building solves the problems of the past but not the future—you can’t predict what art’s going to do.” We are aware of the problem that curators at the Centre Georges Pompidou face with each new installation because programmers in the 1970s thought they could predict where art was heading and what it would need: a museum without walls. But we also know what an extraordinary challenge the spiral of the Guggenheim Museum still offers to artists forty years after its completion. This is exactly what makes it “historic” in the sense I am trying to suggest.

Not only do we not know what art is going to do, it also looks as if one of the main concerns of art was to deceive any prediction, to evade any enlistment. This doesn’t mean that plans for new museums, or for the remodeling of existing ones, should only solve problems of the past, as Rubin put it. The “historic” quality of a project depends on its capacity to generate a margin of play as well as a set of situations to which both the visitors and the artists must react. As far as the museum is concerned, this means breaking with the strictly linear development of a master narrative. Frank Lloyd Wright’s scheme for the Guggenheim Museum represented a drastic move beyond Le Corbusier’s Mundaneum, a museum that developed concentrically as a snail shell, providing no room for any confrontation or short circuits, not to mention the impossibility of introducing a new piece into the game without having to reorganize the entire itinerary. In the Guggenheim Museum, the visitor is allowed, at any moment along the spiral, to take a transversal view, either upward or downward, backward or forward. In a recent show there, EIlsworth Kelly played systematically, and dramatically, both on the constraints that the spiral form imposes and on the possibilities it opens.

A museum is at once a narrative and a system that assumes an architectural form: a narrative that “precipitates”—in the chemical sense—according to constant accretions and redistributions; a system that corresponds to the mapping of diachrony into synchrony, of succession into simultaneity, and through which one has to open a path in some transversal way. When the new Boijmans Museum opened in 1935, it was much criticized for its traditionalism by the adepts of the modern movement. However, due more to its intricate plan than to its technically advanced system of lighting, the building retains an extraordinary quality. Distributed on several levels, with a circular hallway at the crossroads of various possible itineraries, it functions according to an unprecedented principle, mirroring in its very structure the evolution of art—itself ramified, arboreal, bushlike—and the multiple pathways of its history.

We still need to learn from Marx that history is not only a matter of narration. We still need to learn from Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, creators of the French school of Les Annales, that history has to be constantly rewritten according to the needs and anticipations of new generations. In the museum, such rewriting takes the form of new additions and the remodeling of former parts. For the curators at the Boijmans, it meant dealing simultaneously with ancient, modern, and contemporary art. My own move in the exhibition that I curated there is consistent with this.Playing Chess and Cards with the Museum amounts to an experiment in having art from the past working, with no intermediaries, with art from the present and vice versa. It is an experiment in the ways in which history can be dealt with not only according to sequential lines but through simultaneity and the constant confrontations, overlappings, and short circuits of which the history of art is constituted.

3

A more delicate, even painful question concerns the uses and abuses of history and the uses and abuses of architecture in a “museum” like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, a structure, according to its supporters, that is specifically about the nature of memory.25 This issue seems to defy any attempts to deal with it in a seemingly detached and objective way; hence, I will only pinpoint in the most discrete way two problems of special relevance to my argument here.

First, the problem of linearity: Notwithstanding the architects’ efforts to provide visitors with a succession of choices between different itineraries and to induce (here again, I borrow freely from different sources) “a sense of imbalance, distortion and rupture,” the story of the Holocaust unfolds linearly on three levels surrounding “a large hollow interior that resembles another hall of arrival” (itself described as both “a non-place and a central space”)—that is, strictly speaking, another kind of terminal. How are we to deal in a narrative way with an event so beyond measure that it not only evades the grasp but blasts the very notion of it? I do not want to sound polemical, but the way in which the story starts in 1918 and implacably continues to 1945, with General Dwight D. Eisenhower discovering the atrocities of the death camps; the way in which the tale is told to play on the sense of guilt that Western democracies should develop for having refused to welcome the great numbers of refugees who would have otherwise supposedly been allowed to leave Germany; the claim that one would have had to wait until 1942 and the Wannsee Conference for the Nazis to engage in the “final solution”; and, last but not least, the tale abruptly ending on the two interrelated historical destinies left to the Jews after the Holocaust, the State of Israel and the American Jewish community; all the supposed subtleties of the setting lead to the same conclusion: there is no way to deal in critical terms with such an endeavor other than strictly architecturally. At stake is no less than the capacity of architecture to ensure a visible grasp on an unspeakable past—for the enormity of the event, the way in which, as Jean-François Lyotard once put it, it destroys all instruments of measurement, is measured by the way in which it implies the negation of any form of bigness other than the merely quantitative, as well as the total, or totalitarian, elimination of any architectural trace or any archeological remnant of the boundless atrocities that took place on the premises.

There is no other way to discuss such a “monument” in the etymological sense of the word than the strictly architectural. A more general question concerns the different ways in which architecture can relate to history today, the different ways in which architecture can deal with the challenge of history.

This leads to the second problem, that of style: The way in which the architects of the Holocaust Museum played on style reveals the degenerate Nietzschean way in which we now indulge in dealing with history in stylistic terms—starting with the “architectural language” of the Hall of Witness, conceived as “an ironic criticism of early modernism’s lofty ideals of reason and order that were perverted to build the factories of death,”26 and ending, regrettably, with an unbearable touch of so-called concentrationary atmosphere. One is forced to watch a sequence of events in strict chronology down to a horse-stable barrack treated as the canonical representation of German camps. In a way, the Holocaust Museum, in its limitations and given the issues it raises, amounts to an urgent call for the museum to come to terms with history in ways other than the merely retrospective and narrative, in the past tense. An urgent call for architecture to be “historic” in ways other than the stylistic, mimetic, or allegorical. An urgent call for architecture in the future tense, the future of metaphor.

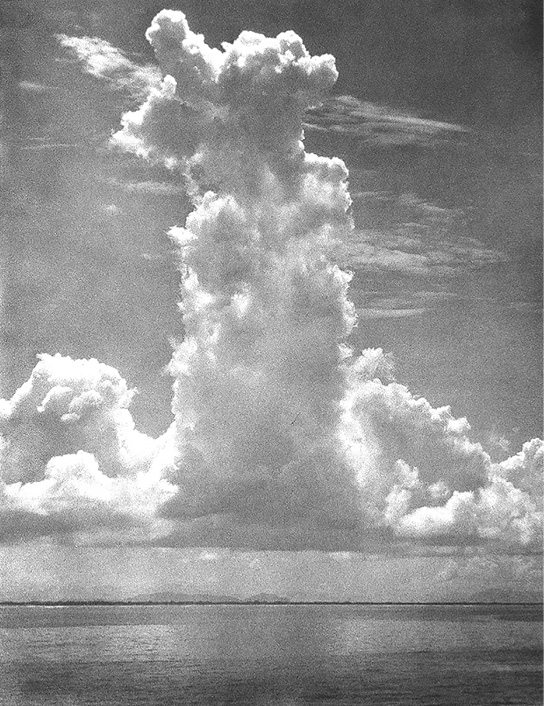

14.1

Edward Weston,The Great Cloud, Mazatlán, Mexico, 1923. Oakland Museum of California, The Bell Fund. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.