Frankfort Freeforall, or the Whatever Cure

MISSY PIGGLE-WIGGLE SAT in the rocking chair on her front porch and ruminated, which is an unnecessarily adult way of saying she was thinking things over. It was a cloudy late summer afternoon. School would be starting again soon. Missy couldn’t believe that she had been living at the upside-down house for so long. She also couldn’t believe that she hadn’t heard from her great-aunt. Months had gone by without a phone call or another letter. Not one single word.

She looked at Lester, who was seated on the porch swing, back feet crossed at the ankles as usual, a cup of coffee held between his front hooves. Wag was curled at Missy’s feet, and Penelope was perched on her shoulder, her head drooping as she fell asleep.

Where was Auntie? Missy wondered. Was she on a pirate ship, bargaining for the return of her husband? Her search could have taken her anywhere at all in the world—to the high seas, to a desert island, to a jungle or a rain forest, or to someplace entirely ordinary. Although really, when you thought about it, what place was entirely ordinary when Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle was in it?

While Missy was ruminating, Harold Spectacle was walking along in the direction of the upside-down house. He passed Melody playing in her yard with Tulip and Heavenly, and he called to her, “The mystery you ordered is in!”

“Yes!” exclaimed Melody.

Harold smiled but his mind was wandering. He was thinking about Missy Piggle-Wiggle. When he reached the end of the path to the upside-down house and saw Missy sitting on the porch, he could feel his heart begin to pound. He twirled his cane, hoping to appear jaunty and confident. Then he tipped his top hat.

“Good afternoon!” he called.

“Good afternoon to you!”

Harold could think of nothing further to say. For a person who spent his days surrounded by books and words, you might have thought something clever would come to him, but it was as if all his words had vanished.

Missy felt tongue-tied, too, and for a moment wondered if the house was playing a trick. Then Penelope, who was now awake, began bouncing up and down on Missy’s shoulder. “Speak up!” she squawked. “Speak up! Somebody say—”

Lester shushed her with a wave of his hoof.

Harold climbed the steps to the porch and leaned on the rail across from Missy.

“Would you like some lemonade?” she asked him, just as he said, “I brought you a book,” and then realized he had left it behind at A to Z Books.

“Disaster, disaster,” whispered Penelope.

Missy ignored her. She smiled at Harold. “What was the book about?”

“The history of Little Spring Valley. That may not sound very interesting—”

“Oh no, it sounds fascinating. I’d like to know more about the town. I love history.” This wasn’t quite true. What Missy loved was magic. But she did want to know more about Little Spring Valley.

“Well, maybe I can take you on a tour of the town sometime,” said Harold.

“Thank you,” said Missy. “That would be very nice.”

After another awkward silence. Harold made a production out of checking his watch, which was a pocket watch that he looked at as if he were an old-time train conductor. “Uh-oh! I must be on my way!” He fled down the path before words could fail him again.

Missy sat back in the rocking chair and tried to relax. She thought about Harold Spectacle and his offer. She thought about Melody. She thought about how the upside-down house was going to be awfully quiet on weekdays once school started.

Then her thoughts turned to Frankfort Freeforall. Like all the children in Little Spring Valley, Frankfort had many good qualities. He was curious and he did well in school. He was an excellent soccer player. He was brave. He was daring. But you couldn’t say he was thoughtful or that he was concerned about other people’s feelings.

“Whatever!” Frankfort declared about five hundred times a day. It was his response to everything.

“Frankfort, give that back to me. I was playing with it,” Linden would exclaim.

“Whatever.”

“Frankfort, you just made Melody cry,” Tulip would say.

“What. Ever.”

“Frankfort, stop chasing Veronica. She’s getting tired,” Georgie would say.

“Whatever!”

Sometimes he said “Whatever” just for the fun of it.

“Frankfort—”

“Whatever!”

Frankfort was a problem. Wag hid from him, and so did Veronica and some of the smaller children.

Missy’s phone rang. “Hello?” she said.

“Missy?” (Missy recognized Mrs. Freeforall’s voice.) “Do you have a moment?”

“Of course.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but I’m sort of at my wits’ end with Frankfort and, well, you’ve worked wonders with the twins.”

Missy could see what was coming. She got right to the point. “Frankfort will need a two-step cure for his Whatever-itis.”

“Oh dear. It’s that bad, is it?”

“Well,” Missy began, and paused, thinking about what to say. One had to be diplomatic when discussing people’s children. “Not only does Frankfort need to curb his behavior, but he needs to stop hurting and annoying others.”

“Absolutely.”

“He also needs to think about how others are feeling.”

“Mm-hmm.”

“In other words, he’ll need the Bubble of Apology followed by a How-Are-You-Doing? pill.”

In the background Missy heard one of the twins cry, “Ow, Frankfort! That hurt!”

“Whatever!”

“Do you have any questions?” asked Missy.

“How soon can you get started?” said Mrs. Freeforall.

* * *

On one of the very last days of summer vacation, Honoriah, Petulance, and Frankfort arrived at the upside-down house early in the morning. Missy knew they’d arrived because she could hear them on the front porch, squabbling over who got to ring the doorbell.

“It’s my turn,” said Petulance. “We said we would take turns, and today it’s my turn.”

“Whatever,” replied Frankfort.

The next thing Missy knew, Penelope was announcing, “It’s the Freeforalls!”

“You’re here bright and early,” said Missy.

“Mom and Dad are already working,” said Honoriah.

“We can’t wait for school to start,” added Petulance. “Then we’ll have something to do instead of waiting for Mom and Dad to do something with us.”

The morning was sunny with a breeze that was almost chilly. When Missy looked at the maple tree in the yard, she noticed that the tips of several leaves had turned bright yellow. Fall was on the way. The sun-warmed air seemed to draw the children of Little Spring Valley to the upside-down house that day. By lunchtime, no fewer than seventeen children were climbing through the house and running around the yard and knitting long, red traily things and making papier-mâché masks in the kitchen.

Frankfort had said “Whatever” 362 times.

Missy, her hair springing from under her straw hat, stood at the front door with her hands on her hips and watched him playing hide-and-seek with Georgie, Linden, and Beaufort. Georgie crawled into one of the best hiding places, which was a spot under the front porch, and Frankfort dropped to his hands and knees to follow him.

“Go away!” Georgie hissed. “I was here first.”

“Whatever.”

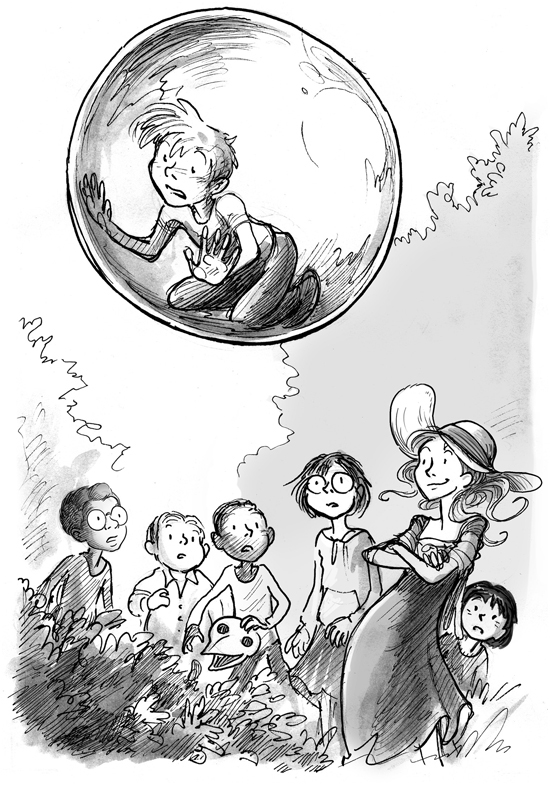

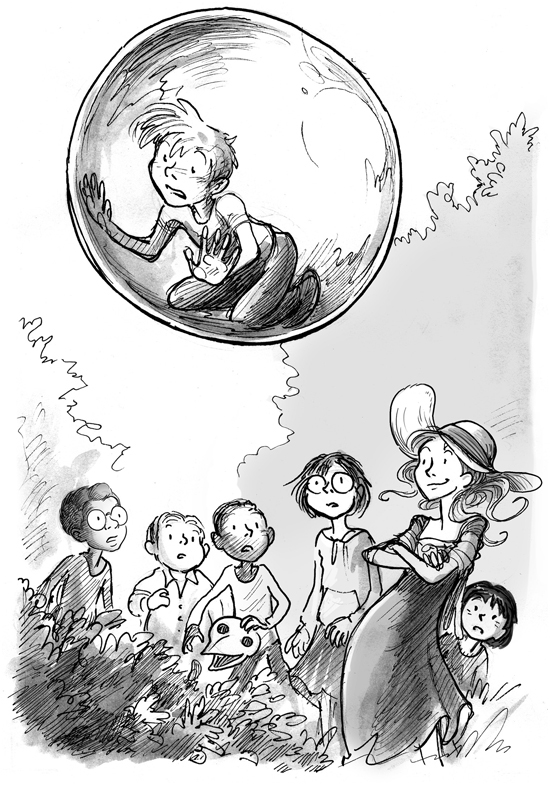

“Okeydokey,” Missy said to herself. She snapped her fingers, and in the next instant, Frankfort found himself rolling around inside an enormous, glistening bubble.

“Hey!” he shouted. “Help!” The bubble began to drift upward.

Everything in the front yard came to a stop.

Frankfort pounded his hands against the bubble. From down below, he looked like a large hamster in an exercise ball.

The children in the upside-down house dropped their knitting and abandoned their masks. They joined the crowd beneath Frankfort and stared up at him.

“Let me out!” Frankfort yelled. “Let me out! Let me out!” He punched the inside of the bubble. It was like punching a marshmallow. He kicked. The bubble bobbled and bounced and floated slightly higher as Frankfort tumbled around.

“Wow, that’s a really strong bubble,” commented Beaufort.

“Let him out,” said Linden.

“Let me out!” Frankfort yelled again.

“You can let yourself out,” Missy called to him.

“How?”

“Apologize to Georgie.”

“No.”

Georgie grinned up at him. “Yeah, say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“Well,” said Missy, “I’m going to go inside and make lunch. I think we’ll have hot dogs today.”

The children took a last look at Frankfort and the bubble and turned toward the house.

“Wait! Wait for me!” Frankfort cried desperately. He ran and ran, pumping his legs against the bubble, which only made him slip and slide and turn somersaults. “I’m sorry, Georgie!” he called. “I’m sorry I was going to take your hiding place.”

The bubble floated downward, landed gently in the yard, and disappeared with a soft, damp pop.

Frankfort held out his arms and examined them. He looked down at his legs. He patted himself all over. “Huh,” he said.

Lunch was a picnic. The children took their plates of hot dogs outside and ate on tablecloths Missy had spread on the ground. Of course Frankfort wanted more than one hot dog, and of course he snatched Veronica’s from her plate, and of course Veronica burst into tears and yelped, “That’s mine!” and of course Frankfort replied, “Whatever.”

I think you know what happened next. Frankfort found himself rolling around inside another bubble. The hot dog was no longer in his hand. It was back on Veronica’s plate, and she was staring at it warily. (What you may not have guessed is that Veronica no longer wanted to eat it. “It has boy germs on it,” she whispered to Melody.)

Meanwhile, Frankfort, hot dog–less, floated above the picnic. For a while, he tried to pretend that he was having fun up there, rolling around in the air, laughing and hooting as if he were in his own private bouncy castle. But no one paid any attention to him.

Missy began to serve ice cream. Frankfort watched his friends slurp on their cones. Missy produced sprinkles (it looked to Frankfort as if she produced them from the sleeve of her dress), and now the cones seemed to glow in the sunshine.

Frankfort sat in his bubble. Whatever, whatever, whatever, he said to himself. He removed a pen from his pocket and jabbed the bubble. Nothing happened.

He pinched the bubble. Nothing.

He scrunched up a great big handful of bubble and gave it a twist. Nothing.

Frankfort stared down at the ice cream party. He thought he could actually smell chocolate ice cream, but that seemed unlikely.

“Frankfort?” Missy called from below.

“What.”

“You know how to get out of the bubble, don’t you?”

Frankfort stared. “Apologize,” he said finally.

“Exactly,” said Missy.

Frankfort put his hands to his mouth and shouted, “Veronica, I’m sorry you’re such a crybaby.”

The bubble swooped higher then, above the top branches of the maple tree. Frankfort crossed his arms and pretended he wasn’t scared. Everyone else probably was, though. He peered down through the limbs of the tree, expecting to see his sisters and friends screaming and jumping up and down. Instead they were helping Missy clean up the picnic. Linden, Beaufort, and Georgie returned to their game.

Whatever, whatever, whatever.

All afternoon Frankfort watched his friends in Missy’s yard. The air grew cool again, and the shadows grew longer. Petulance and Honoriah stood on the porch and looked up at their brother.

“We’re going home now,” Honoriah called.

“Fine,” said Frankfort.

Honoriah and Petulance shrugged their shoulders and began walking back to Merriweather Court. The bubble followed just above their heads, turning corners, occasionally swerving to avoid a street sign or a tree branch. Frankfort sat on the bottom of the bubble, arms still crossed, bouncing along, and sticking his tongue out whenever one of the twins glanced up at him.

The Freeforall children reached their street. They passed the LaCartes’ house, where Della and Peony pointed at the bubble and giggled behind their hands. Honoriah opened the front door, Petulance stepped through it, and then the sisters turned back to the bubble, which was at least four feet wide.

“I guess it won’t fit inside,” said Honoriah, and closed the door.

Frankfort hovered over the porch.

That night the Freeforalls ate a peaceful dinner in their kitchen. The bubble now hovered outside the window. Frankfort glared in at his parents and sisters. This was uncomfortable, but no one missed his shouts of “Whatever!”

“He must be getting hungry, though,” Honoriah whispered to her sister.

“I wonder if he’s safe out there,” Petulance replied.

After dinner the twins put in a call to Missy, who assured them that Frankfort was perfectly safe and also that he knew perfectly well how to get out of the bubble.

It wasn’t until 8:30 that evening that Frankfort shouted in to his mother and asked her if she could please bring the phone outside and dial Veronica Cupcake’s number. Mrs. Freeforall did so, the bubble politely floated to the ground, and when Veronica answered the phone Frankfort yelled, “Veronica, it’s Frankfort Freeforall! I’m really sorry I took your hot dog. That wasn’t nice of me. I’m sorry I called you a crybaby, too.”

“Thank you,” Veronica replied.

The bubble popped then, and Frankfort hurried inside, ate four helpings of lasagna, and went to bed.

You might think that Frankfort had seen the last of the Bubble of Apology, but over the next week, he found himself inside it seventeen more times. The nineteenth and final time occurred on the first day of school. Frankfort pouted in the bubble while he missed both gym and recess. It wasn’t until two o’clock that he finally shouted, “I’m sorry I took your pen, Mrs. Berry!” and was returned to his seat in his new classroom.

At first no one realized that Frankfort’s nineteenth time in the bubble was his last time. Six days went by before Mrs. Freeforall remarked to her husband, “I haven’t seen that bubble in a while, have you, dear?”

Mr. Freeforall looked up from his computer. “Why no, I haven’t.”

“I haven’t heard Frankfort say ‘Whatever,’ either.” Mrs. Freeforall picked up the phone. “Missy!” she exclaimed. “I think the cure is taking effect.”

What Missy wanted to say was, Frankfort is the stubbornest child I’ve ever worked with. Who knew he’d be in that bubble nineteen times? What she said instead was, “Let’s start the second phase. I’ll bring the pill with me the next time I babysit for the children.”

In case you’ve never seen one, a How-Are-You-Doing? pill looks exactly like a gumdrop. Even so, Frankfort was reluctant to take it. Word had gotten around Little Spring Valley about Linden Pettigrew’s gum ball, and Frankfort didn’t want to risk swallowing something that tasted like cilantro or a dirty sponge.

“It’s lemon-lime,” Missy assured him, and was greatly relieved when Frankfort finally bit into it. It wasn’t enough for Frankfort to stop thinking only about himself. Now he needed to start thinking about other people and how they were feeling.

The moment Frankfort swallowed the last bit of the gumdrop, he turned to Petulance and asked enthusiastically, “How are you doing?”

Petulance, who was sitting at the kitchen table eating a pear, was so surprised that the pear slid from her hand and splatted on the floor. “I—” she said as she fumbled for the pear, “I—why do you want to know?”

“You’re my sister,” Frankfort found himself replying. “How are you doing?”

“Well, I had a pretty good day at school, but I’m a little upset because I didn’t do very well on a spelling test, and I studied really hard for it.”

Frankfort felt an unfamiliar feeling spread through his body. “Are you frustrated?” he asked, frowning.

“Yes. And worried, because now Mr. Pasternak probably thinks I’m a bad speller, and I’m not.”

“Hmm,” said Frankfort. “I’m sorry, Petulance.” He went up to his room to think things over.

All that afternoon Frankfort greeted people with a hearty, “How are you doing?”

He learned any number of interesting things. Honoriah was nervous (the good kind of nervous, she explained) because she had decided to try out for the basketball team. Missy was happy that autumn was on the way but nervous (the uncomfortable kind of nervous) because she still hadn’t heard from her great-aunt.

Wag answered the question by placing his paw on Frankfort’s shoulder, squinting his eyes, and concentrating. “Oh!” Frankfort exclaimed. “So that’s how you feel when cats chase you. I never thought about their claws.” And even though Frankfort didn’t have claws, he felt bad about all the times he had chased Wag when Wag didn’t want to be chased.

“How are you doing?” Frankfort yelled over the fence to Della and Peony LaCarte. They were sitting primly on their swing set.

“I’m feeling a little suspicious,” Della replied, frowning at Frankfort.

“But I really want to know how you’re doing.”

“It’s lonely over here,” said Peony finally, and Frankfort decided there might be something he could do about that.

The next morning as the Freeforalls walked to school, Frankfort called out to everyone he saw, “How are you doing?!”

“Great! My grandfather is coming to visit,” said Rusty Goodenough.

“Fine,” replied Veronica Cupcake. “I’m going to get new sneakers this afternoon.”

Frankfort checked in with Georgie Pepperpot’s dog. “He’s having an off day,” he reported to the twins. “Something about his food.”

“How are you doing?” Frankfort asked an old woman he’d never seen before.

“Just fine. Thank you for asking, young man. How charming of you.”

And so it went. Frankfort asked his classmates and Mrs. Berry and the security guard and the librarian and the kindergarteners’ guinea pig how they were doing. He found it especially interesting to learn that some people were unhappy or angry or frustrated or worried. He thought about that as he and his sisters walked to the upside-down house after school that day. The very first person he saw when they arrived was Melody Flowers. She was sitting by herself on the front porch, Lightfoot in her lap.

“How are you doing?” Frankfort asked her. He had the feeling that Melody might not be doing very well, so he asked the question more gently than usual.

Melody looked up at him in surprise. “Okay, I guess.”

“Really?” said Frankfort. He sat beside her. Lightfoot flicked her tail in his direction.

“Well, no.”

“What’s the matter?”

Melody dropped her eyes and stroked Lightfoot’s back. “I still feel like the new kid here,” she said finally. “It’s horrible being so shy.”

“But everyone likes you,” Frankfort told her. “You know that, don’t you? My sisters always talk about how nice you are.”

“They do?”

Frankfort nodded. “And so do Tulip and Veronica. Everyone, really.”

Melody smiled at him. Then Frankfort glanced behind him and saw that Missy was at the door. She was smiling, too.

What Missy was thinking was that sometimes all it took was one gumdrop.