IT WAS A quiet Saturday in Little Spring Valley. Halloween had come and gone, and Thanksgiving was less than two weeks away. The warm weather was over, and the trees were bare, the last of their red and gold leaves lying wetly in gutters. The tourists and weekend visitors had stopped making trips to Juniper Street for ice-cream cones and handmade candles, or to ooh and aah over the windows at Aunt Martha’s General Store. On Spell Street, the Art of Magic had closed its doors until spring.

At the upside-down house, Missy built a fire in the fireplace most evenings. She admired the thick winter coats the animals had grown.

“Where are the children today?” she wondered now. She looked at Lester, who shrugged his shoulders. “It’s a lovely day, but it’s so quiet.” She thought about her great-aunt, who would have said, “Such a time and no one to it.”

“Should I be worried?” Missy asked Lester. She was sitting in the parlor, her feet propped up on the chandelier. Wag was curled beside her, and Lightfoot was curled in her lap, purring. “Month after month without a word from my great-aunt, and today not a soul has come to the door.”

“You have us!” screeched Penelope from her perch.

“So I do,” said Missy. Still, something was missing. “What could it be?” she asked.

Lester looked at her and shook his head. Missy could cure any child in town, but when it came to her own problems, she was …

“Clueless!” cried Penelope, bouncing up and down. “Clueless!”

Missy stood, walked through the kitchen, and let herself out the back door. “Hello, Warren. Hello, Evelyn. Hello, Martha,” she said, stepping around the geese and the duck as she made her way to the barn. “Hello, Trotsky. Hello, Heather,” she said to the horse and the cow in their stalls. She tipped her head back and called hello to Pulitzer in the rafters.

“Whoo,” murmured the owl, since Missy was interrupting his sleep.

Missy looked around at the neat barn and the tidy yard. She sighed. “Nothing to do here.” She walked back to the house. In the parlor she said, “You know, Lester, I think maybe I’m just a bit lonely. I think maybe I need to see a friend.”

Lester nodded wisely, and Penelope shouted, “At last! At last!” Then she swooped across the room, picked up Missy’s wool hat in her claws, and deposited it on Missy’s head. “Go!”

The house opened the front door, Lester handed Missy her pocketbook, and before she knew it, she was hurrying along the path to the sidewalk.

“Blue sky,” Missy murmured to herself. “Cool air. No wind. A perfect autumn day.”

Missy walked toward Juniper Street and began to hum. She turned the corner. Why, she would just take herself down the block to A to Z Books and have a chat with Harold. That ought to cheer her up. Missy approached the store and had put out her hand to open the door, expecting to hear the sneeze, when the door suddenly opened from the other side and Harold stepped out.

“Missy!” he exclaimed.

“Harold! You startled me.”

“I’m sorry,” said Harold. He stuffed his hands in his pockets.

“Where are you off to?” asked Missy. “Closing up early?”

Harold shook his head. “Business is slow, but I left Benny in charge in case someone needs a book.” He tilted his head toward the sun. “I decided it’s too nice to stay inside, so I’m giving myself the afternoon off. I’m going to take a walk around town. Where are you off to?”

Missy shrugged. “I’m not sure.”

Harold held his hand out to her. “Care to join me? I did promise to take you on a tour of the town.”

“I would love to,” Missy replied. She took Harold’s hand, and off they went down Juniper Street, Missy in her wild, wrinkled coat and her wool hat, a pair of green high-heeled boots on her feet, and Harold in his red top hat and tuxedo and his purple shoes. He carried the cane in his free hand, and it went tip-tip-tip-tip along the sidewalk.

For a while, Harold and Missy ambled through town, turning a corner here, a corner there, Harold telling her interesting bits about Little Spring Valley. They passed Rusty Goodenough’s house, where they saw him playing catch in his yard with Tulip and not spying on anyone. They passed Heavenly Earwig’s house, where they saw her run through her front door and heard her mother call from inside, “Oh good. You’re right on time!” They passed Linden Pettigrew’s house, where they saw him sitting on his front stoop eating an apple.

“So many happy children,” said Harold to Missy, and he squeezed her hand.

“Hmm,” said Missy, who was thinking of I Never-Said-itis and Just-One-More-Minuters and alarms and enormous gum balls.

“There’s something wonderful about Little Spring Valley,” Harold went on.

Missy cocked her head at him. “Is there?”

“Yes. But it’s hard to describe.”

“I have a feeling in my bones,” said Missy as she steered Harold toward a large park at the edge of town. “I feel as though something magical could happen at any moment.”

Harold laughed. “I know what you mean.”

Missy paused then, just for a fraction of a second. Just long enough for Harold to think maybe she had lost her footing or seen something out of the corner of her eye. And then they were walking along again, smiling, hand in hand, Harold’s cane going tip-tip-tip-tip.

Ahead of them was a line of trees, and beyond the trees was Edgewood Park. Missy and Harold could hear the squeaking of swings and the shrieks of children hanging from monkey bars. They could smell hot dogs roasting and marshmallows toasting.

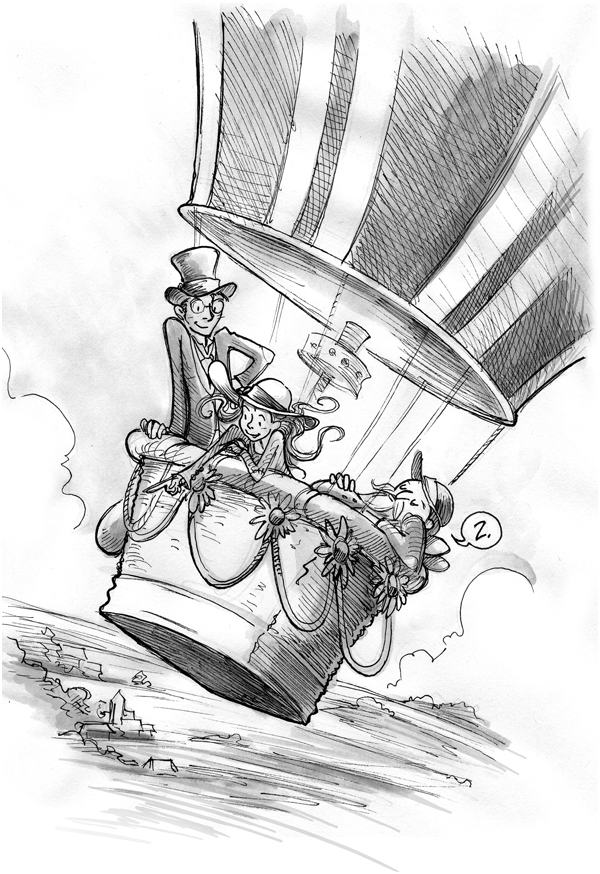

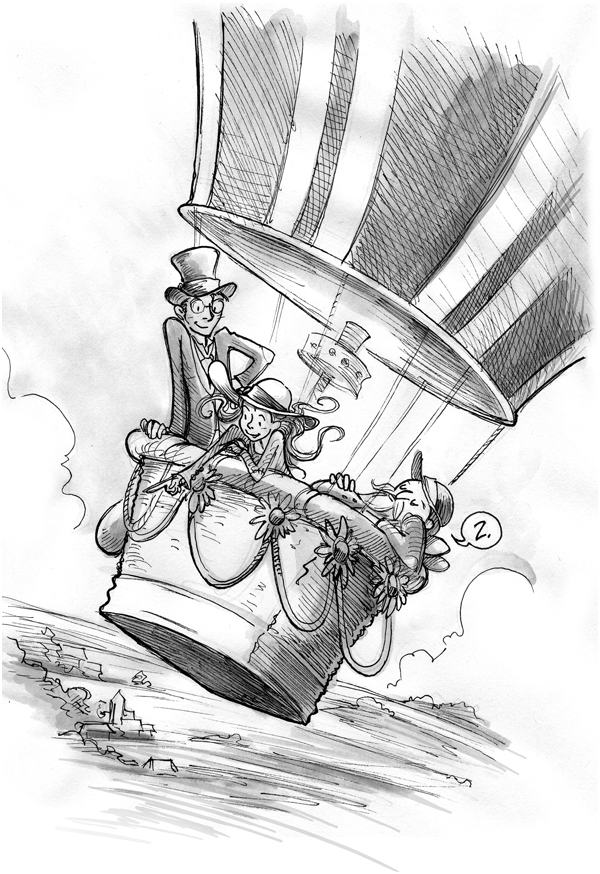

Harold came to a sudden stop. “Well, I never,” he said softly. “Look at that. A hot-air balloon!”

The balloon, taller than a house, was striped red and white, like a peppermint stick, and a small gold pennant flew from the top. Daisies studded the rim of the gondola, looped together with crimson ribbon.

A man with a large round Santa Claus–like belly approached Harold and Missy.

“Where did he come from?” asked Harold. “I didn’t see him before. Just the balloon. And then all of a sudden, there he was.”

The man was wearing a lavender brocade vest with daisies for buttons and little shoes with toes that curled upward and ended in bells.

“He looks like a jester,” Harold whispered to Missy. “Or an elf.”

Missy personally felt that someone wearing a red top hat and carrying a cane for no reason shouldn’t comment on what anyone else was wearing, but she simply smiled.

“Balloon rides!” called the man. “The adventure of a lifetime!”

“Did you hear anything about balloon rides today?” Harold asked Missy. “You’d think it would have been in the paper.”

Missy smiled again and shrugged her shoulders. She felt like Lester.

“Well, let’s go!” cried Harold. “We can’t miss out on the adventure of a lifetime.”

He pulled Missy toward the man, who said, “Abercrombie Terwilliger, at your service.”

“How much is a ride?” asked Harold. He began fumbling in his pocket.

“For you and Missy Piggle-Wiggle—free,” said Abercrombie.

Harold turned to Missy. “You know him?”

“We’re two peas in a pod” was Missy’s reply. “Now, let’s not look a gift horse in the mouth. Come along. Abercrombie is offering us a ride for free.”

Abercrombie extended his hand to Missy and helped her into the basket. Harold followed her, and before he knew it, they were floating gently above Little Spring Valley, the park growing smaller and smaller beneath them.

“Just pretend I’m not here,” said Abercrombie. He handed Missy and Harold a picnic basket, and then he appeared to fall asleep.

Harold peeked into the basket. “Hot chocolate and cake and biscuits and roast chicken,” he said. “This is quite a picnic.” He glanced at the sleeping Abercrombie. “I hope he knows what he’s doing.”

“I’m certain he does,” replied Missy. She peered over the rim of the gondola. “Look, there’s Juniper Street and A to Z Books.”

“There are the school and the library.”

“There’s the Freeforalls’ house.”

“There’s your house, Missy!”

Missy looked where Harold was pointing. She could make out the upside-down house, squatting before the pasture and the barnyard. “Oh dear,” said Missy. “Trotsky has let himself out of his stall again.”

“Pulitzer will keep him in line,” said Harold. “Don’t you worry.”

“Pulitzer is asleep.”

“So is Abercrombie,” Harold pointed out, glancing at the fat little man, who was dozing with his chin resting on his chest.

Missy looped her arm through Harold’s. “This is lovely, the best kind of tour. I always like seeing things from above. There’s nothing like viewing your life from a different perspective.”

The balloon bobbed along. Missy and Harold sat on benches in the gondola and ate their unexpected picnic.

“Who knew,” said Harold, “that one day I’d be sitting in a balloon with you high above town drinking hot chocolate?”

“There’s magic everywhere you look,” Missy replied.

Just as they were swallowing the last of the hot chocolate, Abercrombie snorted himself awake and began to release air from the balloon. The sun was low in the sky and the chilly air felt even chillier.

“Time to land,” said Abercrombie, and before they knew it the balloon was bumping lightly down into Edgewood Park.

“It looks like everyone has gone home,” said Harold, and Missy thought he sounded sad.

“Day is done,” Missy replied practically.

Abercrombie alighted from the gondola and helped Missy and Harold to the ground.

“Thank you, Abercrombie!” called Missy as she and Harold walked through the fallen leaves.

“I feel I should pay him something,” said Harold. “Should I pay him?” He turned around and saw nothing but trees and slides and swings and the ball field. “He’s gone! Abercrombie is gone and so is the balloon. How did that happen?”

Missy once again looped her arm through Harold’s. She patted his hand. “That was an afternoon to remember.”

“Yes,” said Harold, and he scratched his head.

Missy and Harold walked back to Juniper Street. When they reached A to Z Books, Harold went inside to help Benny close the shop. “See you tomorrow?” he asked Missy. “I could drop by.”

“See you tomorrow,” she replied.

Missy walked back to the upside-down house. Every few steps she skipped a little. She passed Melody’s and saw her climbing into the car with her father. “I’m going to a sleepover at Tulip’s!” called Melody.

Missy skipped along. She reached the upside-down house and hurried down the walk. As she stepped onto the porch, the house gallantly opened the front door for her.

“Thank you,” said Missy.

Lester hurried to Missy’s side and pointed at something on the table in the front hallway.

“Ah, the mail,” said Missy. She picked up a handful of envelopes. The address on the very first one was in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s loopy handwriting.

“Auntie!” exclaimed Missy, and she opened the envelope.

Dear Missy,

I’m sorry you haven’t heard from me in such a long while. I didn’t expect to be out of touch for this long. Pirates are so unpredictable. I wish I could tell you where I am, but that isn’t possible. I believe I am close to finding Mr. Piggle-Wiggle, and I don’t want to put him in danger.

I hope all is well at the upside-down house. I miss Wag and Lightfoot and Lester and the others, but I know you’re caring for them as well as I would. Can you stay in Little Spring Valley a bit longer? If you’re running low on money, look for the silver key in the attic.

It means a great deal to me that I can trust you.

In haste,

Auntie