To begin with a metaphor appropriate to a book about food: If this book is the fruit of much reading, eating, traveling, and studying, then the core of the fruit consists of the six articles, three on Aztec food and three on Inca food, that I published in shorter versions in Petits Propos Culinaires between 1985 and 1991. But the tree that produced the fruit was planted long before that by an extremely gracious letter that I received from the editor of Petits Propos Culinaires, Alan Davidson, in return for what was the most banal of letters subscribing to his then newly founded journal. That directed me from the interest and concern common, one hopes, to all competent family cooks toward a more historical and scientific focus for my efforts. For his friendship and encouragement over the years, I cannot thank Alan enough.

Once the project had taken root, the kindness of many libraries helped it to grow. First and foremost I must thank the library system of Yale University, whose amazing resources never seem to come to an end and which endangers researchers by exposing them to too much material and too many paths to explore, rather than too little and too few. The tolerance and helpfulness of the staff is as boundless as the resources, and I am grateful to them all.

Other libraries that I have consulted must also be acknowledged, including the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, which allowed two total strangers who wandered in off the Piazzetta to read the world’s only surviving copy of the Littera mādata della insula de Cuba de Indie. The Biblioteca Urbaniana, the library of the British Academy, and the Instituto Italo-Latino Americano, all in Rome, introduced me to many of the sources.

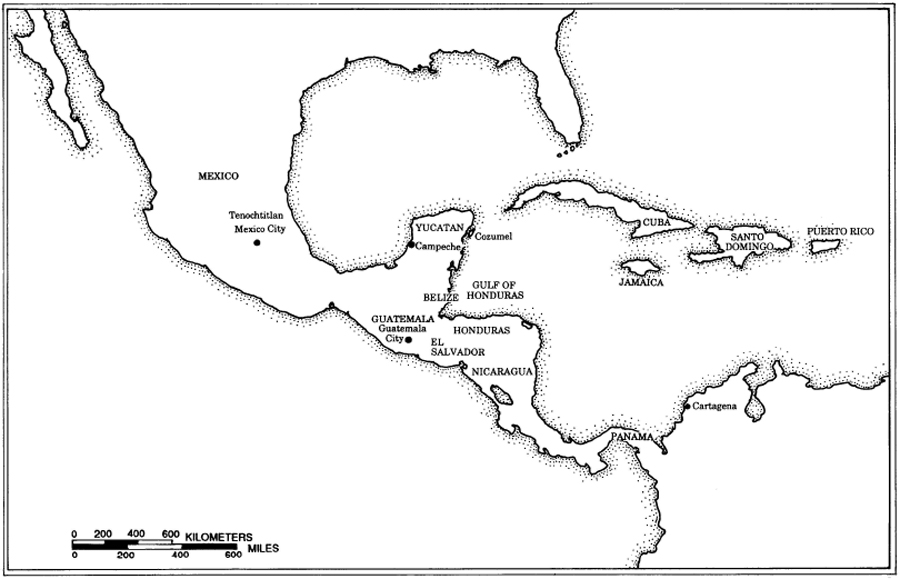

North and Central America. Map by Jean Blackburn.

Many individuals also aided me with advice and comments. From the anthropology department of Yale University they include Floyd Lounsbury, Harold Conklin, and Richard and Lucy Burger. José Arrom, professor emeritus of Spanish, was also a great help. R. S. MacNeish and Charles Remington gave advice in their fields of specialization. From other parts of the world David Pendergast, Robert Laughlin, my Harvard thesis advisor Evon Vogt, Payson Sheets, Dennis and Barbara Tedlock, Steve Houston, Karl Taube, Arturo Gómez-Pompa, and Justin and Barbara Kerr all aided my efforts to discover more about the food of the Classic Maya. Doris Heyden and Louise Burkhardt did the same for the Aztecs, and special gratitude is due to Lawrence Kaplan for laying to rest the myth about Pierio Valerio and the beans of Lamon.

South America. Map by Jean Blackburn.

Many people from other fields added to my knowledge. Jane Buikstra edified me as to the difference between the menu and the ingredients, which I hope will be evident in the pages that follow. My colleagues in the amorphous ranks of food historians also encouraged me with their insights. They are too numerous to mention, but I thank them all.

The translations in the pages that follow are my own, and I am of course responsible for any errors. The only exceptions are the translations by others from Nahuatl, which were checked by my resident Nahuatlato, Michael Coe, and corrected if he thought it necessary. The botanical names have been checked with Mabberley (1989).

And the first shall be the last. More than anyone else, I must thank my husband, Michael Coe, who over the years has seen his treasured library ravaged, his dinners disrupted, and his wife either absent or absent-minded. To him, for all his interest, encouragement, and every other possible sort of assistance, this book is dedicated.