The Aztecs

We know far more about the day-to-day life of the Aztecs than we do about the life of the Maya and the Inca. That we know so much is entirely due to the intellectual curiosity of one man, the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. A scant decade after the conquest of Tenochtitlan he was collecting material on the Aztec way of life from native informants, having it recorded in Spanish and Nahuatl, and commissioning illustrations from native artists. It is not enough to call him a great ethnographer born before his time, because from the point of view of a culinary historian he is far superior to a mere ethnographer, as he gives exhaustive lists of foodstuffs and dishes, and few if any ethnographers do that. In fact, one could call him one of the fathers of culinary history. His zeal resulted in his ending his life under a cloud, although his manuscripts were securely stored where they, to our great good fortune, escaped fire, flood, and military depredations to surface in the late nineteenth century. The following royal cedula, dated April 22, 1577, expresses the opinion of Philip II of Spain on ethnographic investigations.

By some letters that have been written to us from the provinces [Mexico] we understand that friar Bernardino de Sahagún of the Franciscan order has composed a Universal History of the most notable things of that New Spain, and it is a copious compendium of all the rites, ceremonies and idolatries which the Indians used when they were pagans, divided into twelve books, and in the Mexican language; and while it is understood that friar Bernardino did this with the best intentions, and hoped that his work would be useful, it is my opinion that this book should not be printed or circulated in any manner in this country, for weighty reasons; and thus we order that as soon as you receive this cedula, you use much care and diligence to get hold of these books, omitting no originals or copies, and send them immediately to our Council of the Indies, who will see to them; and be warned that you are not to allow any person to write anything concerning the superstitions and way of life these Indians had, in any language, because this is advantageous to the service of God our Lord, and our own. (Códice franciscano 1941: 249)

Fortunately Philip’s orders were not faithfully observed, and besides Sahagún’s magnificent compilation we have many other sources, although they may seem run-of-the-mill compared to his. The conqueror himself wrote letters to Philip’s father, Charles V, and while Cortés was more interested in aggrandizing himself and denigrating his enemies, the letters contain items of interest. The most famous narrative is that of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who was an eyewitness of the events he describes but wrote it all down long afterward, when he was an old man living in Guatemala and the oldest surviving conquistador.

With these, and with all the other sources, we must always remember that they are in no way objective accounts. Everyone wrote with a prejudice, or a political agenda, or a cause in mind. The conquest of Mexico was not an operation undertaken in a spirit of perfect consensus. The crown had its wishes, which mostly boiled down to more revenue. The religious had theirs, which involved more souls for Christ, but also more power, revenue, and territory for their religious order, or for the secular clergy, if that is what they happened to be. The conquerors turned colonists also wanted more revenue, but they wanted it for themselves; they wanted dowries for their daughters and an opportunity to set their sons up in life. Every source we read reflects these differing points of view, especially on matters concerning the Indians, and they must be read with such concerns in mind.

Who were the Aztecs, whose way of life Philip II found so distasteful, if not downright dangerous? The Aztecs were originally a barbarian tribe from the deserts of northern Mexico whose wanderings led them to the valley of Mexico some time in the fourteenth century. It was by no means uninhabited country: there were major settlements along the margins of the lakes in the valley, and not too far distant lay the ruins of two great ancient cities, Teotihuacan and Tula.

The valley of Mexico, today one of the most polluted places on earth, must have seemed a place of astonishing lushness to the desert tribe. The lakes were one of the end points of the North American flyway, with incredible numbers of migratory birds arriving every fall to spend the winter. When they departed in the spring the permanent avian residents made their nests in the reeds and among the marshes. The Aztecs, sent to live in the swamps by the Culhuacans, who had prior claim to more solid ground, adapted to their circumstances with a speed that amazed those of Culhuacan.

And they went and found them content and multiplying, and saw that they were eating the snakes roast and stewed in a thousand manners and tastes, with another thousand dishes and soups made of fish and lake frogs and the eggs of juhuiles and even the flies that sprang from the foam on the water, and these were the first of these inventions and edibles, as before they did not use them, and necessity and hunger forced them to innovate, and thus they were fat and happy. (Dorantes de Carranza 1902: 6)

It is evident that their lake-centered diet was part of their mythology as a nation, because as the Aztecs began expanding their territory, at the expense of their neighbors, they used their foodstuffs as a weapon. The erstwhile desert dwellers had obviously become completely acclimated.

You know how tasty are the viands which we obtain from our lake, let the guards take [to Coyohuacan] small ducks, large ducks, fish, and all sorts of things which breed on our lake, which they cannot obtain and greatly desire, and there, at their gates, roast, toast, and stew all this, so that the smoke will enter their city, and the smell will make the women miscarry, the children waste away, and the old men and old women weaken and die of longing and desire to eat that which is unobtainable. (Anon. 1987: 89)

By dint of such stratagems, as well as plain force of arms, the Aztecs expanded their territory, until at the time of the arrival of the Europeans they controlled land up to the Guatemalan border and sent their merchants far beyond, to what is now Nicaragua and Panama. It was not an empire, or even a state, as we know it. It was a looser sort of dominion and a patchwork one at that, with some of the other cities in central Mexico being independent. In part this was to provide an opportunity for a sort of ritualized enmity, the “Flowery War,” which gave the warriors a chance to prove themselves, as well as supplying sacrificial victims for the gods, who preferred the blood of captives. Other areas were allowed to keep their indigenous rulers as long as the proper tribute was paid to the Aztecs. This haphazard structure greatly helped the Europeans, as many of the Aztecs’ subjects were tired of their overlords and their heavy demands for tribute, and only too glad to jump from the frying pan into the fire.

It used to be thought that the Aztecs were softened up for the European conquest by a series of portents and omens that preceded the Europeans’ arrival. Present-day wisdom considers most of these to have been invented by the occupying forces after the conquest, and if we compare the eight prodigies that foretold the collapse of the Aztec empire with the phenomena that are supposed to have occurred before the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence in 1492, the similarities are certainly striking. There are the same strange lights in the sky, the same portentous lightning strikes, the same bizarre animal behavior. Perhaps the most widely disseminated explanation for the capitulation of the Aztecs has to do with their belief that the culture hero, Quetzalcoatl, who among other things had practiced the cultivation of cacao, had at some point in the past sailed off to the east, promising to return some day, and the arrival of the Europeans was interpreted as the god keeping his promise. But the Emperor Motecuhzoma II (Montezuma is a Spanish mangling of his name, which means “angry like a lord”), whatever may have been in his mind at first, devised an efficient and indeed rather scientific method for determining whether the new arrivals were gods or humans. He accomplished this by ordering his messengers to present Cortés and the Europeans with two kinds of food, one suitable for gods and the other for mortals, and asking the messengers to report the reactions of the strangers.

The landing of Cortés and his troops in 1519 was not the first time that Europeans had come to Motecuhzoma’s attention. The earliest expeditions to the coast of Yucatan will be treated in the Maya section; here it is enough to know that the preceding summer Juan de Grijalva had touched the coast of Mexico and Motecuhzoma had been apprised of the fact. How he had learned of this landing is unclear, because while many secondary sources blithely assure us that runners brought Motecuhzoma fish fresh from the sea, the existence of a system of runners and the necessary posthouses is not substantiated by any early texts. Alvarado Tezozomoc (1944: 519) says it was a macehual, a commoner, who of his own volition made the journey from the coast to tell Motecuhzoma of the new visitors to his shores. He was no mortal macehual, however, because he was put into custody while his story was checked, and he vanished there. Other histories say that Motecuhzoma ordered a system of runners and posthouses set up especially to report news of the strangers, while still others have individuals going to Tenochtitlan to deliver reports, or in one case paintings of the Europeans and their equipment, done by Motecuhzoma’s artists on white cloth, and taking anything from an impossible twenty-four hours to three or four days for the journey.

Perturbed by these reports, Motecuhzoma sent his magicians to consult an oracle. The oracle sent a gift to Motecuhzoma, a gift of chilchotes, a very hot variety of chiles; xitomates, probably what we know as tomatoes; cempoalxochitl, Tagetes lucida, or Tagetes erecta, also known as Mexican tarragon and related to our annual garden marigolds (British marigolds are our calendulas); and green maize ears. What the oracle intended should be done with this is not clear, because on a later visit it demanded that Motecuhzoma do penance by abandoning delicacies, flowers and perfumes, and sexual relations with women; eating only cakes of michihuautli and the seeds of Amaranthus or Chenopodium; and drinking only water boiled with parched bean powder, presumably as a penitential replacement for his usual chocolate drinks. Motecuhzoma observed this fast for eighty days. The theme of fasts and feasts is a recurrent one in accounts of Aztec food, and of course one that was also familiar to the Europeans from their own religious practices.

There is no record that the 1518 encounter between Grijalva’s Europeans and the local inhabitants involved any sort of food tests to determine if the former were mortal or divine. We will have to assume therefore that the population offered them the foodstuffs that become almost a standard refrain in the later narratives, the birds, bread, and fruit. The Europeans reciprocated, giving their visitors standard shipboard stores. The visitors ate some and sent the rest up to the emperor in Tenochtitlan.

He categorically refused to sample the ship’s biscuit, the fat salt pork, and the dried meat given by the strangers, on the pretext that they were the food of the gods, but had his hunchbacks taste them, and they said that the bread was sweet and soft. By orders of Motecuhzoma it was put into a gilt jícara [calabash], and covered with the richest mantles. The priests formed a procession, with incense and the songs consecrated to Quetzalcoatl, and took it to Tollan [Tula], burying it in the temple of that god. (Orozco y Berra 1880, 4: 47)

By the time Cortés had landed on his shores one year later, Motecuhzoma was ready to proceed in a more scientific and experimental fashion. No matter who he thought the new arrivals were, and it was possible that they were gods, after all, he was going to offer them a test meal and find out.

Western readers often accuse the Aztecs, and all New World peoples, of submitting too soon, of not resisting sufficiently, of suffering from cowardice and lack of guts. In part this goes back to the European myth of the inferiority of the New World, which was set in motion by Columbus on his return from his first voyage, when he is said to have described the shallow-rooted trees to Queen Isabella, and she is reputed to have answered that if the trees had shallow roots the people were probably shallow and worthless also. In part this accusation of cowardice stems from the arrogance and thoughtlessness of the modern world, which forgets that the New World had never seen anybody remotely approaching the strangers with their ships, horses, and cannons. It is worthwhile contemplating the effect on us of the arrival of a combination of the Second Coming and a landing of beings from outer space before we condescend too much to Motecuhzoma and mock his efforts to determine whether the threatening presences on his coast were mortal or divine.

And he sent the commanders, the strong ones, the braves, to purvey [to the Spaniards] all that would be needed of food, among them turkeys, turkey eggs, white tortillas; and that which they might demand, as well as whatsoever might satisfy their hearts. They would watch them well. He sent captives so that they might be prepared if perchance they [the Spaniards] would drink their blood. And thus the messengers did it.

And when they [the Spaniards] saw this, they were nauseated, they spat, they blinked, they shut their eyes, they shook their heads. For the food, which they had sprinkled and spattered with blood, greatly revolted them, for it strongly reeked of blood.

And thus Motecuhzoma did it, for he thought them gods; he took them for gods; he paid them reverence as gods. For they were called, they were named “gods come from the heavens.” And the black ones were said to be black gods.

Later they ate white tortillas, grains of maize, turkey eggs, turkeys, and all kinds of fruits [there follows a list of twenty-five varieties of “fruit,” including four varieties of sweet potato, sweet manioc, avocados, and five kinds of cactus fruit]. (Sahagún 1950–1982, 12: 21–22, retranslated)

Another account tells us that the Europeans were hesitant about eating the food for mortals and the Aztec ambassadors had to coax them. Even more fearsome was the chocolate, in what seems to have been the Europeans’ first encounter with that beverage.

The two Aztecs tasted the different foods and when the Spaniards saw them eating they too began to eat turkey, stew, and maize cakes and enjoy the food, with much laughing and sporting. But when the time came to drink the chocolate that had been brought to them, that most highly prized drink of the Indian, they were filled with fear. When the Indians saw that they dared not drink they tasted from all the gourds and the Spaniards then quenched their thirst with chocolate and realized what a refreshing drink it was. (Durán 1964: 266)

Unaware of the examination to which they had been subjected, the Europeans landed and began marching toward the distant highland capital, Tenochtitlan. Bernal Díaz records the constant gifts of food they were offered by the inhabitants of the settlements along the way: fowls and honey; fowls, roasted fish, and maize; fowls, maize bread and “plums”; fowls, fruit, and roasted fish; “plums” and maize bread; fowls, maize bread, and fruit. Such gifts were considered signs of peace, although we know that the people the Europeans passed differed widely in their views of the Aztecs, and surely of the Europeans as well. The fowls they presented to the marchers were probably, but not certainly, turkeys, there being many other large fowl that the donors could have used for their gifts. The “plums” are Spondias fruit.

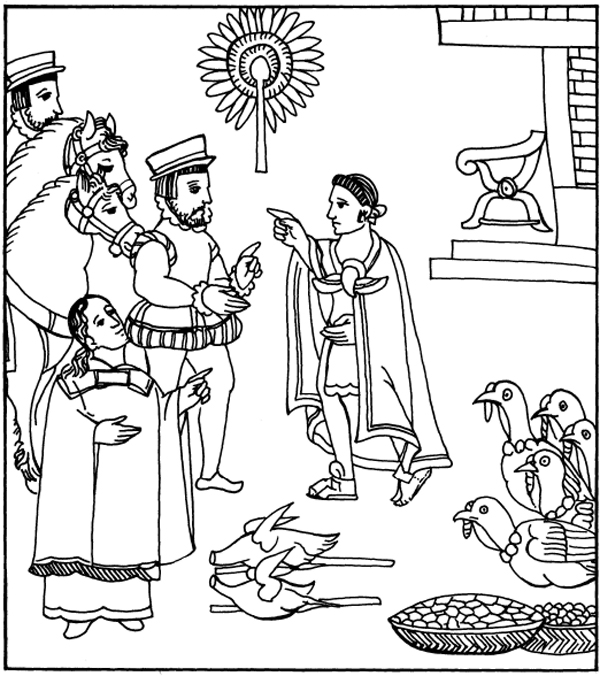

The Europeans encounter the Tlaxcallans. Adapted by Jean Blackburn, from Munoz Camargo 1981: 266 recto.

Motecuhzoma was not the only person who wished proof of the heavenly or earthly origin of the visitors. Somewhere en route, and the sources differ among themselves as to whether it was in Tlaxcala, one of the enemy enclaves in Aztec territory, or outside of Tenochtitlan itself, an even more complex test was devised and administered.

They sent Cortés five slaves, incense, domestic fowl, and cakes, so that if he was, as they had heard, a fearsome god, he could feed on the slaves, if a benevolent one he would be content with the incense, and if he was human and mortal he would use the fowl, fruit and cakes that had been prepared for him. (Hernández 1945: 207)

At last Cortés and his men reached Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, which Bernal Díaz in a famous passage of his narrative compares to an enchantment from the legend of Amadis, as well as quoting the opinion of his fellow soldiers who had fought in the wars of the League of Cambrai and thought that Tenochtitlan in the middle of its great lake looked exactly like what they had seen of Venice in the middle of its lagoon. Once within Tenochtitlan Bernal Díaz gives us an even more famous, from the culinary point of view, description of what is called Motecuhzoma’s banquet but was really just a routine daily meal when he was not under the obligation to fast.

For his meals his cooks had more than thirty styles of dishes made according to their fashion and usage; and they put them on small low clay braziers so that they would not get cold. They cooked more than three hundred dishes of the food which Motecuhzoma was going to eat, and more than a thousand more for the men of the guard; and when it was time to eat, sometimes Motecuhzoma went out with his nobles and mayordomos, who showed him which dish was the best or of which birds and things they were composed, and as they advised him, so he ate, but he went out to see the food on rare occasions, and only as a pastime. I heard it said that they cooked the meat of young boys for him; and as they had so many different dishes of so many different things, we could not see if it was human flesh or something else, because every day they cooked him fowl, wattled fowl, pheasants, native partridges, quail, domestic and wild ducks, deer, peccary, reed birds and doves and hares and rabbits, and many other birds and things that are native to this country, that are so numerous I could never finish naming them, and so will leave them. I know that after our captain reprimanded him for sacrificing and eating human flesh, from that time forward he gave orders that that sort of food not be cooked for him. Enough of this, let us return to the manner that they served him during his meal, and it was thus: if it was cold they made him a fire of glowing coals made from the bark of certain trees, which did not smoke; and the odor of the bark of which they made those coals was most fragrant; and so that they did not give him more heat than he wished they put in front of him a screen worked in gold, depicting idols. He sat on a low, richly worked soft seat, and the table was also low, and made in the same manner as the seat, and there they put the tablecloths of white fabric, and some rather large handkerchiefs of the same, and four very beautiful and clean women gave him water for his hands out of a kind of deep acquamanile, which they call jicales, and to catch the water they put down a kind of plate, and gave him the towels, and two other women brought him the tortillas; and when he began to eat they put in front of him a thing like a door of wood all painted up with gold so that he could not be seen eating; and the four women stood aside, and there came to his side four great lords and elders, who stood, and from time to time Motecuhzoma chatted with them and asked them questions, and as a great favor gave each of those old men a dish of what he had been eating; and they said that those old men were his near relations and councilors and judges, and the plates of food that Motecuhzoma gave them they ate standing, with much reverence, and without looking him in the face. They served him on Cholula pottery, some red and some black. While he was eating it was unthinkable that there be any disturbance or loud speech among his guard, who were in rooms near that of Motecuhzoma. They brought him fruit of every sort available in that country, but he ate very little of it, and from time to time they brought him some cups of fine gold, with a certain drink made of cacao, which they said was for success with women; and then we thought no more about it; but I saw that they brought more than 50 great jars of prepared good cacao with its foam, and he drank of that; and the women served him drink very respectfully, and sometimes at meal times there were very ugly hunchbacked Indians, who were very short of body and deformed, and some of them told ribald stories; and there were others who must have been jesters, who made witty remarks, and others who sang and danced, because Motecuhzoma was very fond of pleasures and songs, and he ordered the leftovers and the jars of cacao given to them. The same four women removed the tablecloths and returned with water for his hands, which they did with much reverence. Motecuhzoma spoke to those four old noblemen of worthwhile things, and they took their leave with great respect, and he rested. When the great Motecuhzoma had eaten then all of his guard and many of his house servants ate, and it seems to me that they took out more than a thousand plates of dishes that I have spoken of, as well as more than two thousand jars of chocolate with its foam, as they make it among the Mexicans, and no end of fruit. And then there were his women and his servants, breadmakers and cacao makers; it was a great establishment that he had. . . . And I will say what I had forgotten, and it is good to return to it, that when Motecuhzoma was at the table eating he was served by two other very graceful women who made tortillas kneaded with eggs and other nourishing ingredients, and the tortillas were very white, and they were brought to him in plates covered with clean cloths, and they also brought him another kind of bread which was like long rolls, made and kneaded in another manner with nourishing things, and what is called pan pachol in this country, which is a kind of wafer. They also put on the table three highly painted and gilt pipes, which contained liquidamber [Liquidambar styraciflua?] mixed with some plants which are called tobacco [Nicotiana sp.], and when he had finished eating, after they had sung and danced for him, and cleared the table, he took the smoke of one of those pipes, just a little, and with this he fell asleep. (Díaz del Castillo 1982:184–186)

This passage took on a life of its own during the nineteenth century, when Lewis Henry Morgan, an early American ethnographer who wrote on the Iroquois and has since been credited by the Marxists with independently developing the materialist conception of history, attacked it as being all essentially a lie, a piece of European propaganda to make the achievements of European might more imposing. Bernal Díaz lied when he said the meal took place in a palace; it was a large joint tenement occupied by Motecuhzoma and his fellow householders. He lied when he said that every bowl contained a different dish; all those dishes were really individual servings of the common meal, brought from the common kettle in the common cookhouse. It was the universal custom of the American Indian family, said Morgan, to have one meal a day, breakfast and dinner being characteristic of civilization, a condition to which, for material reasons, they could not aspire. The fact that no women or children ate with the Aztec men was another trait marking their low position on the ladder to civilization, Morgan said. It showed an imperfect appreciation of the female sex, an appreciation which presumably was developed to its highest degree in his Rochester, New York, of the 1870s. In short, historians like Bancroft and Prescott had been deceived in what must have been one of the most massive disinformation campaigns in history, and all the European sources they had read were false (Morgan 1950). Morgan’s interpretation was praised by Engels and incorporated into his own work, where it remains as part of the sacred texts of Marxism.

Nobody takes Morgan’s revision of Aztec ethnography seriously today, but neither should we accept Bernal Díaz’s account uncritically, because there is much in it that smacks more of contemporary European court etiquette than of Aztec practice. As an antidote to his view let us look at two banquets described by Sahagún’s native informants, always remembering that these are extraordinary meals that we must use for comparison because we have no accounts by an Aztec informant of one of Motecuhzoma’s meals.

The first banquet is a baptismal one and therefore took place frequently, although with different degrees of lavishness. If an infant was born on an auspicious day it was baptized immediately. Those born on unauspicious ones had the situation remedied by their parents, who held the baptismal feast on a more fortunate day. The actual ceremony took place at sunrise, and all the children were invited and fed; unfortunately what they were fed goes undescribed. The elders addressed the mother and the newborn, giving the latter the first taste of the moral lectures and fine oratory that the Aztecs revered so highly.

It is not clear if the feast took place on the same day as the ceremony. Some time on the day of the feast, we are not told when, the guests arrived and were seated in rank order, women apart from men. All of Sahagún’s informants were males, high-status males, so our information about women’s activities is skimpy and sometimes incomprehensible. The seated guests were each offered a plate with a smoking tube that contained tobacco and fragrances, and sweet-smelling flowers to wreathe their heads, hands, and necks. The food arrived after the guests had begun to smoke and enjoy the scent of the flowers. It came in baskets, some filled with different kinds of breadstuffs and others holding the deep dishes that Sahagún describes using the Spanish word cazuelas. This word means both the dish and the food contained in it, a concoction that is usually semiliquid and stewlike, in this case made with meat and fish and, although it is not mentioned because assumed, chile. Another source on baptismal feasts gives the menu as a mulli (sauce), or potage, with beans and toasted maize among the ingredients. Before eating every guest took a bit of food and dropped it on the ground as an offering to the god Tlaltecuhtli. After the guests had eaten their fill, the leftovers, as well as the baskets and cazuelas, were given to the servers. The end of the meal was signaled by the presentation of chocolate, which every male guest received in a jícara, a calabash cup, with a special stirring stick placed across it. Wherever the women were eating they did not get chocolate but what Sahagún called a gruel, almost certainly one of the many Aztec drinks made with maize or other dough, diluted with water and sometimes cooked after dilution to thicken it. It could be varied with a great range of flavorings, and many different sauces could be floated on the surface. The remains of the chocolate, and probably the gruel as well, went to the servers, and the contented guests rested in their seats.

Those unhappy with the hospitality they had received left, angry and complaining. The host was informed of this and had to invite them back the next night to feed them again and make up his deficiencies. Between the two meals, the primary and the propitiatory, there took place what Sahagún said occurred after every banquet, although his informants do not mention it during other banquets. This was when the old men and the old women, who were the only ones allowed to freely indulge in the weakly alcoholic pulque, came to be entertained. Depending on availability, which probably meant the season, they were given iztac uctli, white pulque, made from the sap of the maguey or century plant (Agave spp.), which despite being succulent and spiny is not even remotely related to the cactus family. If that was not available there was always ayuctli, or water pulque, made of honey and water cooked with certain roots. The server put a large vessel of the drink before the guests and then served them in rank order, highest to lowest. If he thought they were not getting drunk rapidly enough, he reversed the order and served the lowest first. When the guests got drunk they began to sing, but never two together, Sahagún said. The others talked, laughed, told jokes, or laughed at the jokes of others. That was the conclusion of every banquet, Sahagún’s Aztec informants said.

Baptisms were obviously fairly common. A rarer and grander banquet was given by a well-established member of the merchant caste. It was a once-in-a-lifetime effort, because it was considered a poor thing to die without having made such a splendid gesture, giving lustre to one’s name, thanks to the gods, and pleasure to friends, relatives, and the leaders of the merchants. There is a long list of preparations to be made: first of all the purchase of cacao, and the teunacaztli (Cymbopetalum penduliflorum), the Aztec spice of choice for chocolate, both major trade items which may well have been among the goods imported by the merchant himself. There were other chocolate spices to be bought, and it is significant that chocolate and its spice constellation are mentioned first; it was not just a mere drink to wash down the food. Other shopping had to be done: fowl, crockery, baskets, drinking vessels, chocolate stirrers, and three different kinds of cooking fuel had to be purchased, including one kind of dry cane specifically for providing the heat to steam the tamales.

It was not only edibles, dishes, and fuel that the host had to obtain. He had to recruit his friends and relatives to help serve the meal, as well as singers and dancers to entertain the guests and diviners to predict auspicious days for the festivities. It was not everybody who could be entrusted with gracefully distributing flowers, smoking tubes, food, chocolate, and other drinks, nor could just anybody be asked to receive and seat the guests. The people selected for these tasks had to be well brought up, well spoken and good looking, not mean low people but noble and courtly ones.

The complex etiquette involved in simple acts like giving and taking smoking tubes and flowers reminds us that merchants among the Aztecs were almost a paramilitary force whose visits to distant trading partners often foretold an incursion by the Aztec army. The giver of smoking tubes and flowers mimicked the gestures of a warrior, reiterating the central place of the warrior in Aztec ideology. The smoking tube went from the left hand of the donor to the right hand of the recipient, while the plate that accompanied it went from right hand to left hand, the gestures reproducing the taking of darts and shield by an Aztec soldier. The flowers that went from the left hand of the server to the right hand of the guest were the sword flowers; the ones that went in the opposite direction were called chimalxochitl, or shield flowers.

Handing the food around did not seem to have any military significance, but there was a correct and proper way to do it. The food, in this case meat cooked with chiles, was served in an individual deep dish which was to be held in the center of the right hand. Tamales, which were passed around in a basket, were held in the left hand and dipped into the meat with its sauce.

But much had to be done before the food could be served. The festivities began at midnight, with offerings of flowers to the gods and to the drums. At a signal a priest entered and wafted incense to the four directions. Dancing could begin after that, but the merchants did not dance; they sat in their rooms around the courtyard of the merchants’ building, which sounds similar in architecture to a caravansary or a Turkish ban, receiving newly arrived guests and offering them flowers. The dances were performed by senior military men. Before dawn, some of the participants ate small black mushrooms, while others drank chocolate. The mushrooms were not a culinary item but a hallucinogenic one, causing visions which made some sing, some laugh, and some weep, as they saw their future foretold. When the intoxication wore off they described their experiences to the other guests. As dawn approached songs were sung, and then there was another offering, the ashes of which were buried in the center of the courtyard so that the children and the grandchildren of the merchants would be as rich as their parents and grandparents.

As the sun rose the food was served to all the guests sitting in their rooms, followed by more flowers and more smoking tubes. Later on, food was given to the lower-status people who had been invited, as well as the old men and the old women.

The passage about the activities of the women is unclear, probably because the male informants themselves were unsure of what the women were doing. The ladies went to the house of the women, entering five by five, and six by six, each putting maize that they had brought on a mat and also contributing a mantle made of ixtli, or maguey fiber, to the host to help cover expenses. They were given food but not chocolate; in this case it was replaced by a gruel made of the seeds of chía (Salvia hispanica). Whether these women were the wives of the male guests, or hired helpers, or the old women previously mentioned, we do not know. We do know that the merchants, who were as given to moral lectures as their fellow Aztecs, often invoked the elders, the fathers and mothers of the merchants, so that there must have been women of considerable status.

That concluded the action for that day, but on the following day, possibly early in the morning as so many banquets seem to have been in the Americas, there was more eating, drinking, and handing out of smoking tubes and flowers. The guests this time were intimates, the closest friends and relatives of the host, and woe betide him if there was not enough left over from the first day to serve them and feed them. If there was enough food, crockery, fuel, and chocolate left over, that was splendid; it was an omen that the host would live to give many more such feasts.

But even such a success did not exempt him from the severe lectures by his elders, the mothers and fathers of the merchants. As always when there was a possibility that someone might succumb to vainglory, the advisability of balance was stressed. The merchant, glowing with the success of his feast, was warned not to succumb to pride and sloth and not to give up traveling the weary dusty paths with heavy burdens on his back. This was advice like a rich mantle, said the fathers and mothers; the host should take it and cover himself with it. The banquet of the successful merchant ended on this dampening note. We have no notice of any drinking by the elderly terminating the proceedings, although it may have been such a standard occurrence that it was taken for granted.

Certainly these two Aztec banquets, described by the Aztecs themselves, give us very different pictures from the famous one of Bernal Díaz. Where are all the tables and table linens he speaks of? Where in Bernal Díaz is the major role played by chocolate? What has become of the early morning feasting? It is best to treat the Bernal Díaz account with caution, not with the totally dismissive attitude of Morgan, but questioning some of the finer details of cuisine and etiquette that the Spanish soldier crowding with his fellows into Motecuhzoma’s dining hall did not understand and therefore replaced with descriptions of European customs.

There is one very important thing, however, that can be learned both from the conclusion of the Aztec merchant’s banquet and the fasts and feasts of Motecuhzoma, and that is the all-pervading dualism of Aztec thought. They were constantly looking at both sides of the coin. When Sahagún’s informants write about the merchants and their merchandise in the marketplace they do the same thing: contrasting the good merchant and his or her quality goods with the bad merchants and the nasty stuff they sell. In food the effort was to maintain equilibrium between abstinence and indulgence, and when the Europeans arrived and introduced their meat-heavy diet and new sources of alcohol, the Aztec elders pointed out to them that it was this overindulgence in meat and drink that was causing the catastrophic population decline. It was equilibrium that was important, good things were a gift of the gods, “so that we would not die of sadness, our lord gave us laughter, sleep, and sustenance” (Sahagún 1950–1982, 6: 93). The Europeans, who tried to aggregate this tradition to their religious fasting and penance as understood by Christianity, had difficulties, because for the Aztecs it was a way to please the gods and earn favors from them, rather than a way of expiating sins, whether of the individual or of humanity.

The belief that life in this world was a ceaseless search for balance and moderation was inculcated by lengthy homilies to the children about, among other things, food and eating. Lectures of this sort were a common literary form among the Aztecs, and many of them have survived.

Eighth: Listen! Above all you are to be prudent in drink, in food, for many things pertain to it. You are not to eat excessively of the required food. And when you do something, when you perspire, when you work, it is necessary that you are to break your fast. Furthermore, the courtesy, the prudence [you should show] are in this way: when you are eating, you are not to be hasty, not to be impetuous; you are not to take excessively nor to break up your tortillas. You are not to put a large amount in your mouth; you are not to swallow it unchewed. You are not to gulp like a dog, when you are eating food. . . .

And when you are about to eat, you are to wash your hands, to wash your face, to wash your mouth. And if somewhere you are eating with others, do not quickly seat yourself at the eating place with others. Quickly you will seize the wash water, the washbowl; you will wash another’s hands. And when the eating is over, you are quickly to seize the washbowl, the wash water; you are to wash another’s mouth, another’s hands. And you are to pick up [fallen scraps], you are to sweep the place where there has been eating. And you, when you have eaten, once again you are to wash your hands, to wash your mouth, to clean your teeth. (Sahagún 1950–1982, 6:124, retranslated)

The effect of such teachings continued under the European overlords. Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, bishop of Puebla and viceroy of New Spain during the 1640s, commented on the measured tempo of Indian meals, as well as the scantiness of their food, which gives him the title of his chapter: “Of the Indian’s Parsimony in His Food.”

The Indians’ ordinary sustenance (and the extraordinary is very rare), is a bit of maize made into tortillas, . . . and they put a bit of water and chile in a mortar of clay or wood, and wetting the tortilla in water and chile, that food is their sustenance. . . .

If at times they eat more than chile and tortillas they are very natural things, roasts, and some dishes of the country, and they usually do it to honor some superior, religious or secular . . . and not to please themselves.

And on other occasions I have seen them eat with great deliberation, silence, and modesty, so that one knows that the patience that shows in all their habits is shown in eating as well, and they do not allow themselves to be rushed by hunger or the urge to satisfy it. (Palafox y Mendoza 1893: 61–62)

What so impressed Palafox y Mendoza as an example of temperance was the Indians’ daily food, which he said would have given Saint Francis a lesson in poverty had he known about it (1893: 48). The European religious who were contemporaries of Palafox y Mendoza, the poorest of whom ate several vegetable or fish dishes a day, received nothing but scorn from the bishop and viceroy. He probably did not know that before the conquest the Indians practiced fasting, when prescribed by their religious calendar, far more rigorously than what he had described, which seemed to him to be a fast but was merely the daily diet.

The simplest fast, and the one used in all three of the culinary cultures we are going to investigate, was to abstain from salt and chile. Other fasts could include eating “bread” made of maize that had not been soaked and cooked with lime. Before the New Fire ceremony, which occurred every fifty-two years, some priests fasted for a year, the rest of the priests for eighty days, and the lords for eight days. The plebeians fasted too but not, we are told, so rigorously. Durán was horrified by the fact that there were no exemptions from the fasts: children, pregnant women, everybody had to fast (Durán 1971: 223).

There was a permanent contingent of fasters in Tehuacan. In their case fasting seems to have been used as a route to visions, in the fashion of the better-known North American vision quests. We have no knowledge of the visions they received, but it sounds as if in this case the fasting had a broader purpose than just spiritual benefit to the individual in question.

And the chaplains in like manner were four youths who had to fast four years . . . Each one was given only a blanket of thin cotton and a maxtlatl. This is a loincloth with which they gird themselves and cover their private parts. They did not have more clothing than this, neither by night nor by day, although in winter they found the nights quite cold and their bed was the hard ground with a stone as a pillow. They all fasted four years, during which time they abstained from meat and fish, salt and chile. They ate not more than once a day, at noon. Their meal was a tortilla which, it is said, weighed about two ounces, and a bowl of beverage called atolli. They ate nothing else, neither fruit nor honey nor anything sweet, except for every twentieth day which were their festival days, like Sundays with us. On these days they were allowed to eat whatever they had . . . The demon appeared to them many times, or so they pretended . . . The great lord of Mexico, Moteuczoma [sic], took great pleasure in knowing about the practices of these fasters and about their visions, because he thought their service a very special one and acceptable to the gods. (Motolinía 1951:125–126)

If food was hedged about with prohibitions, fermented liquor was even more so. There was, of course, no distilled liquor until the arrival of the Europeans, but there were many kinds of fermented drinks. Alcoholic liquids could be made from maize, honey, pineapples, cactus fruits, and many other things. The most important, which we have encountered in the Aztec version of the Aztec banquet, was pulque, a name of Antillean origin that replaces the Nahuatl uctli. It was made from certain species of the Agave, or century plant, or maguey, a spiny rosette-forming plant which is not a cactus, belonging to the Agavaceae family. When, after years of growth, the maguey is about to shoot up a flowering stalk, the bud is cut out and the plant produces great quantities of sweet juice for about two months. This juice, today called aguamiel, or honeywater, can be drunk as it is, boiled down to make syrup, boiled down more to make sugar, or fermented into pulque or vinegar. Pulque could be flavored with many roots and fruit, but the simple version is a whitish liquid with a peculiar but not unpleasant taste. Some of the additives were reputed to make it much stronger, but without them pulque contained only a few percents of alcohol.

There are different stories as to who was permitted to drink pulque. Cooper-Clark says that it was old men and women over seventy who had children and grandchildren (Cooper-Clark 1938, 1: 98). Motolinía said it was permissible for those over fifty, because that was when the blood turned cold, and pulque warmed it and made it easier to sleep (Motolinía 1903: 314). In any case, only a few small cups were allowed. At weddings and certain religious festivals the young were given pulque; one feast was even called “when the children drink pulque,” but it was always in strictly limited quantities. Drinking was acceptable, intoxication was not.

Old Aztec women, those over seventy, were allowed to drink. From Cooper-Clark 1938, 3: 71 recto.

Pulque drinking must have been thought of as plebeian, because Motolinía says lords, princes, and warriors made it a point of honor not to drink it, preferring to drink chocolate, which was the prestige drink (Motolinía 1903: 315). Warriors did not all abide by this code, because Sahagún tells us the sad tale of a Tlacateccatl (a corps commander, the leader of eight thousand warriors) from Quauhtitlan, the nobleman Tlachinoltzin:

He drank up all his land; he sold it all. And when he had come to the end, he went on—he began with his house, on the morrow he would drink up [the value of] the wood or the stones. In this way he would buy pulque. When he came to the end [of his possessions], when there was nothing more salable, then his women spun [and] wove for others in order to buy pulque.

This Tlacateccatl, a valiant warrior, a great warrior, and a great nobleman, sometimes, somewhere on the road where there was travel, lay fallen, drunk, wallowing in ordure. (Sahagún 1950–1982, 6: 71)

This was by no means the only edifying story of this nature. Teuhchimaltzin was supposed to have visited an enemy court which had no prohibitions on excessive drinking. He waited until midnight, when king and courtiers had drunk themselves into a stupor, and then cut off the king’s head and put it into a bag along with some of the king’s insignia and jewels, and headed for the border. Another lord killed his elder brother when he found that he had not reformed as pledged from the vice of drunkenness, and concubines met the same fate if they indulged, because some sources say that women were either not allowed to drink alcoholic drinks at all or had to wait until they reached a ripe old age. Even selling pulque was a capital offense for a noblewoman who sheltered King Nezahualcoyotl during a period of troubles.

It happened that he entered the house of a widow, a noble lady, at nighttime, and saw that she had a great vineyard [maguey plantation] not only for herself and for her household, but traded in it, which was a thing prohibited by law and much watched for and punished by the kings who were his predecessors. This so vexed and angered him that he could not suffer it and slew the woman, whose name was Tziltomiauh. He said that although he was fleeing from one particular enemy, who was Tezozomoc, he was not frightened of the commoners of the kingdom, who were those who most destroyed it. The most pernicious thing that destroyed them and made them into beasts, was wine [pulque] in excessive quantities, and because of this they who caused the damage must die. (Torquemada 1943, 1:117)

The laws on the matter were simple and draconian, although the penalties for straying from the path of moderation differed for nobles and plebeians, the latter being given one more chance than the former.

Thus the drunkard, if he was a plebeian, had his hair cut publicly in the market square, and his house was sacked and torn down, because the law said that he who deprived himself of his good judgment was not worthy to have a house but could live in the fields like an animal; and the second time he was punished with death; and if he was a noble the first time that he was caught committing this crime he was punished with death. (Ixtlilxochitl 1985: 140)

Such affairs of mortals were replayed on a cosmic scale in the encounter between the gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. The former was the culture hero, the inventor of the arts, the master of all the Aztec status symbols, the cacao and cotton, as well as the gold and jade and fine feathers. He dwelled in Tula at that mythical time when all the common Aztec crop plants grew to enormous size in those dry cold uplands, where even tropical cacao flourished. Tezcatlipoca was the war god, the god of the sorcerers, the supreme deity, neither good nor evil but all-encompassing. Together with his sorcerer confederates he prepared a dish for Quetzalcoatl: greens, chiles, tomatoes, green maize, and beans stewed together. They also prepared pulque, which they blended with honey. The story is a long one, and I will omit the details of how they gained admission and how Quetzalcoatl ate the stew but persisted in refusing the pulque. Finally the entreaties of the sorcerers overwhelmed him and he tasted a drop of pulque, and then a cup, and then many more cups, until he was totally drunk. From this fall, and it does not seem too biblical a term, came his exile from Tula, his departure to the east, the shrinking of all the gigantic crops to the size we see them today, the transformation of the cacao trees into mesquite bushes, and the myth that someday he would come home from the eastern sea. If one believes that the Aztecs thought Cortés Quetzalcoatl returned, then Quetzalcoatl’s immoderate behavior may be said to have paved the way for the European conquerors.