The Inca: Vegetable

Turning from the animals and minerals, we come to the vegetable kingdom and deal first with the goosefoot or pigweed family, Chenopodiaceae, which has several domesticated members in the New World.

Chenopodium ambrosioides was called epazote in Mexico and paiko in Peru. It appears to have been used for flavoring in both places.

Thei sente me an Hearbe that in Peru thei call Payco, thei be certaine leaves . . . and as thei come drie thei are verie thinne: and beyng tasted, thei have a notable bightyng, that thereby thei seeme to bee very hotte. (Monardes 1925, 2:13)

Several species of Chenopodium were grown for their seeds in Peru and provided edible leaves for greens as well. Chenopodium pallidicaule (cañihua) is an extremely-high-altitude semidomesticated plant in Peru, where it grows at an altitude of up to 3,600 meters in the Andes. More important is Chenopodium quinoa, or quinoa, also a plant of high altitudes, although it cannot survive at the heights reached by cañihua. The seeds of the cultivated quinoa may be whitish, red, bicolor, or yellow; the seeds of the wild varieties are always dark. The seeds are covered with varying amounts of bitter saponins, which must be washed off before preparation.

Second place [after maize] among the crops which grow above the earth goes to that which is called quinoa, and in Spanish “millet” or “small rice,” because the seeds and the color are somewhat similar. The plant which bears the seeds resembles pigweed, both in its growth and the leaf and the flowering spike, which is where the seeds are borne. The tender leaves are eaten by the Indians and the Spaniards in their stews, because they taste good and they are very healthful. The seeds are eaten in soups, cooked in many different ways. The Indians make a drink from quinoa as they do from maize, but that is only in regions where they lack maize. (Garcilaso de la Vega 1945, 2:178)

Besides entering into gruels and soups and stews, quinoa seeds were also toasted and ground and made into various forms of bread or mixed with condiments, fat, and salt and the resulting balls steamed. The seeds of cañihua were treated in the same way.

Another high-altitude plant used for seeds and leaves was a lupine (Lupinus mutabilis), tarwi or chocho. It is a totally different plant from the chocho of the Caribbean (which is Sechium edule), thus proving once again the treachery of common names. The seeds of other species of lupines were eaten in the Old World, but the eating of lupine leaves seems to have been confined to cattle in the Old World. The seeds are beanlike and high in protein, which is not surprising because lupines, peas, and beans all belong to the family Leguminosae. Peruvian lupine seeds have to be boiled and then soaked for several days to get rid of their bitterness. Improperly treated they are poisonous. The water they are boiled in is a useful insecticide. Once processed, the seeds are recorded as having been eaten with chile and onions. There are no Allium species in South America, but there is another bulbous plant, Nothoscordium andicola, now classed as belonging to the family Alliaceae if not the genus Allium, which is described as tasting like an insipid garlic and possibly was used in ancient times.

A mountain climate means frost and hail and storms, against which desirable domesticated plants should be able to protect themselves and the investment of time and effort made by their growers. Root crops provide the remedy to these conditions, and among them the potato is preeminent.

The potato (Solanum tuberosum) was domesticated in the highlands of Peru between 3700 and 3000 B.C. Travelers visiting Peruvian markets today see a range of potato varieties undreamed of in their homelands. The tastes and textures vary as much as the looks, and Peruvians consider our commercial potatoes watery, insipid, and boring.

Although always a major foodstuff, the potato seems to have suffered ideological downgrading in Peru. We have archaeological evidence for the Inca resettling conquered tribes off their potato-growing heights into the maize-growing valleys. Despite the fact that the Inca were of highland origin themselves, they consistently exalted maize and ignored what must have been their ancestral staple, the potato. The fact that maize was the principal ingredient in chicha, the beer which was a vital ingredient in Inca social exchanges, may well explain their emphasis.

The most important highland root crop, after the many varieties of potato, is oca (Oxalis tuberosa). It is a member of a family, found in both the Old World and the New, which provides us with many weeds and some houseplants. The leaves and young shoots of oca are edible but sour, from the acid that gives it its generic name. The tubers are the most important part of the crop, and they may be white, yellow, or reddish. Like many other Peruvian roots they come in two classes: the sweet, which may be eaten raw, cooked, or sun-dried and made into caui, which is described as tasting like dried figs and was used as a sweetener before cane sugar was available; and the bitter, which is freeze-dried and made into a storable product called ckaya. Ckaya contains more protein, niacin, and minerals than chuño, which is made of bitter potatoes treated in the same fashion. Oca, any other root crop, and even maize can be fermented into a product called tokush, which is said to smell like vomit and not taste very good either.

Another tuber is provided by a familiar family of decorative plants that usually goes unmentioned when New World domesticates are listed. Perhaps the terminological tangle is the reason for this silence. The edible watercress, a plant of European origin, now carries the Latin name of Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum. An obsolete name is Nasturtium officinale. What are popularly called nasturtiums belong to the genus Tropaeolum, which is of South American origin. The flowers and leaves of some species were eaten, and Cobo describes using the flowers in salads, as is done today (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 398). He does not mention the dodge of making imitation capers by pickling the buds. Linnaeus named the genus Tropaeolum from the Greek word for a trophy, the victors’ display of the weapons of the vanquished. To Linnaeus the round leaves of the nasturtium, with their central stem, looked like shields, and the red-streaked yellow flowers resembled blood-stained golden helmets. It is not the leaves or the flowers of Tropaeolum tuberosum, mashua or añu in Quechua and isaño in Aymara, the other major highland language, that are eaten, but the tubers. The plant is said to be very drought resistant, and according to Vilmorin, the prominent French seed firm which attempted to introduce many exotic crops, including oca, mashua, and ullucu, into nineteenth-century France, the tubers are not affected by frost as long as they stay in the ground (Vilmorin-Andrieux 1885).

Chewed raw, isaño, which is the root of the plant, is somewhat bitter. It is very sharp, and so bites the tongue that it is impossible to eat it, however, cooked, it becomes sweet. (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 367)

When boiled like carrots or potatoes, the tubers are watery and have a rather unpleasant taste, although the perfume is agreeable. In Bolivia, where the plant is extensively cultivated in high mountain districts, the people freeze the tubers after boiling them, and they are then considered a delicacy and are largely consumed. In other places they are eaten in a half-dried state, after having been hung up in nets and exposed to the air for some time. It is, therefore, not surprising that the quality of the fresh tuber appears to us to be very indifferent, since, even in its native country, it is not eaten until it has undergone special preparation. (Vilmorin-Andrieux 1885: 354)

The tubers had a reputation for being anaphrodisiac, while the oca was believed to be an aphrodisiac. After the conquest this became rather a joke, but the Inca apparently took these qualities of isaño or añu seriously:

This root has the quality of suppressing the venereal appetite according to the Indians. They claim that the Inca kings of Peru carried loads of this food as supplies for their army, so that when the soldiers ate it, they would forget their wives. (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 367)

The last of the three high mountain tubers which Vilmorin-Andrieux tried unsuccessfully to introduce into Europe was the ullucu (Ullucus tuberosus). This is related to New Zealand spinach, both plants being members of the Basellaceae. It is described as an insipid starchy root and apparently never did well in Europe. Cobo (1890–1893, 1: 368) says it comes in the same colors as oca and resembles it, and he calls it gluey. In its native country it was freeze-dried or fermented and could be cooked with dried meat or made into a soup with potatoes.

Vilmorin-Andrieux (1885) missed two other high-altitude roots, maka (Lepidium mayenii) and llakhum (Polymnia sonchifolia). The former belongs to the same genus as the common European cress (Lepidium sativum), which is not to be confused with the watercress which we have just discussed. It was capable of producing a crop of roots in the highest and coldest parts of the Andes, but today it is only cultivated in the Junín highlands. The llakhum or yacon Cobo describes as follows:

Each plant gives three to six, and sometimes more, roots, which are the size of middling turnips, although they do not come to a point like turnips. They are sweet and watery, earth-color outside and white inside, and tender like a turnip. They are eaten raw like a fruit and taste very good. They are even better if they are dried in the sun . . . They are a marvelous thing for sea voyages, because they keep a long time. I have seen them taken on the sea and lasting more than twenty days, and because they are so juicy they get sweeter and are very refreshing when it is hot. (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 365–366)

This catalog of roots should not be taken to mean that greens were neglected. Indeed, there were so many that earlier writers despaired of ever being able to catalog them all.

It is difficult to list all the greens, because there are so many of them and they are so small. It is enough to say that the Indians eat all of them, the sweet and the bitter alike. Some of them are eaten raw, as we eat lettuces and radishes, some of them cooked in soups and stews. They are the food of the common people who did not have an abundance of meat as the rulers did. The bitter greens . . . are cooked in two or three waters and dried in the sun and stored for the winter time when greens are not available. Such is the diligence that they apply to finding and preserving greens to eat that they do not overlook anything, even the algae and water worms that live in the rivers and gullies are gathered and prepared for their food. (Garcilaso de la Vega 1945, 2: 189)

There were also starchy roots on the coast. One, raqacha or arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza), was described by the Europeans as a purplish carrot, reasonably enough, as they are kin, both being Umbellifers. The Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening (Chittenden 1974, 1: 181) says that they are to be used in the same way as potatoes and that they are “very palatable and easily digested.” Another is the fleshy rhizome of Canna edulis and therefore a close relative of the cannas which used to be planted in flower beds in front of railroad stations, in the days when we had flower beds and railroad stations.

The tuberous rhizomes contain starch, and when they are roasted in an earth oven . . . produce an edible substance with a sweet taste. In Cuzco, during the religious festival called Corpus, which by order of the viceroy Toledo replaced the ancient festival of R’aimi, according to a traditional custom they consume a lot of this rhizome cooked, as it is a specialty of the season. (Yacovleff and Herrera 1934–1935: 312)

The fact that achira, which is the native name, does not grow above 2,000 meters and had therefore to be carted up to Cuzco to be a major part of a festival that replaced one of the most important pre-Columbian ones suggests that it enjoyed some special importance in earlier times.

The mention of edible algae a few paragraphs back leads us to another resource that was fully exploited. Seaweeds were harvested and eaten fresh on the coast or dried into sheets or blocks and traded into the highlands. This cochayuyo consisted of many different genera: Porphyra in the south of Peru, Gigartina, Ulva lactuca, Durvillea antarctica, and others in the north. Freshwater algae were also consumed, blue-green algae of the genus Nostoc being eaten raw or processed for storage. In postconquest times Nostoc was made into a dessert by being boiled with sugar.

Among the fruit trees which were used in Peru was the pepper tree (Schinus molle), a common street tree with drooping branches and small leaves which is planted in southern California. This pungentsmelling tree produces the pink peppercorns that were recently in vogue but were subsequently found to be carcinogenic, or at least potentially harmful.

Among these fruits we may include that of the tree called mulli, which grows wild in the countryside. It produces long narrow bunches of fruit in the form of red berries the size of dry coriander seeds. The leaves are small and evergreen. When ripe the outside of the berry is sweet and soft and very tasty, but the rest is very bitter. A beverage is prepared from these berries by gently rubbing them with the hands in hot water until all the sweetness has been extracted: care must be taken not to get the bitter part or the drink is spoiled. The liquid is strained and kept for three or four days until it is ready. It makes a delightful drink, being full of flavor and very wholesome . . . If mixed with the maize beverage the latter is improved and made more appetizing. If the water is boiled until it thickens a very pleasant syrup is left. The liquid, if placed in the sun with the addition of something or other, becomes sour and provides a splendid vinegar . . . The tender branches make excellent toothpicks. (Garcilaso de la Vega 1945, 2:182)

The author of this description does not tell us whether the beverages had time to become lightly fermented or not, but a superior chicha, a beerlike fermented drink, was among the products made from the molle, as the pepper tree is now known in its native country.

It produces a little red fruit in racemes like the willow of which the Indians make chicha, and it is so strong that it makes one drunk more than that which is made of maize and other seeds, and the Indians consider it more valuable and a delicacy. (Cobo 1890–1893, 2: 84–85)

Passion fruit (Passiflora spp.) are another New World domesticate, although there are also a few species native to the Pacific area. Most of them are vines that are cultivated for their aromatic fruit, which vary in size from that of peas to that of medium melons. The name does not come from any property of the fruit but because the complex flowers seemed to the early explorers to contain the symbols of the passion of Christ. Cobo (1890–1893, 1: 457) says that in the flower we can find the lashes Christ received, the crown of thorns, the column, the five wounds, and the three nails. He found the fruits of some species sour, others delicate, and one that could be eaten skin and all. He poked fun at the Spanish name granadilla, “little pomegranate,” saying the similarity was very slight indeed. Actually the resemblance is not as farfetched as he seems to think, because both fruit contain a mass of crunchy seeds surrounded by a more or less juicy covering.

The paqay (Inga feuillei) figures in the eyewitness description of the conquest of Peru by Pedro Pizarro, a much younger half-brother of the leader of the enterprise, Francisco Pizarro. It is a confusing fruit because it is also called guaba, but it is not the same as the guava (Psidium guajava). Nor is it the same thing as the Mexican pacaya (Chamaedorea spp.), the bitter but edible flowerbuds of a palm. Pedro Pizarro, writing long after the event, tells us how an Indian, who they thought was named Apoo, though that was actually his title rather than his name, showed up with a basket of these fruit to offer the Europeans while they were marching toward the place that later became Cajamarca. He presented the fruit to Hernando Pizarro, another of the brothers, and was knocked down and kicked for his pains. Understandably, when he returned to Atahualpa, one of the two claimants to supreme power in the civil war then going on, he described the invaders as “a pack of bearded thieves who had come out of the sea” (Pizarro 1978: 28). The fruit itself is portrayed by Cobo:

These pods are two or three fingers wide and one finger thick, the skin is tough and leathery, it is green outside. Inside there is a row of seeds as big as broad beans [European Vicia faba], each covered with a white spongy, sweet substance, which is rather similar to cotton dipped in syrup . . . This fruit is more of a snack than a thing of substance, because even if a man eats a basketful of pacaes, he is neither satisfied nor surfeited. (Cobo 1890–1893, 2: 45)

Another fruit, the rukma or lucuma (Lucuma bifera), seems to have been cultivated enough to have developed superior varieties. However, once a superior tree was identified, there was no way that it could have been propagated, because the sources are unanimous in saying that the practice of grafting was unknown in the New World. The seeds of a selected tree, if cross-fertilized, would give an assortment of progeny, none of them genetically identical with their desirable parent.

The fruit is the size of a medium pomegranate, round with a point on the upper part; it has a thin and tender skin so that it can be eaten without peeling, and even when it is ripe the skin is between green and yellow in color. The pit is very similar in smoothness, size, and aspect to a chestnut, even though the shell is harder than that of a chestnut. The meat inside is similar to a chestnut also, and may be eaten roasted, but it is not usually eaten because it is insipid. The flesh of the lucuma is very yellow, hard, and not juicy, and somewhat hard to swallow, and not of a very good taste, which is why the fruit is not highly thought of. There are some large lucumas, larger than quinces, somewhat tapered, somewhat darker outside and juicier inside. (Cobo 1890–1893, 2: 23–24)

The fruit which obtained the highest praise were the almonds of Chachapoyas (Caryocar amygdaliferum). They were luxury goods long before the arrival of the Europeans, appearing in early tombs on the coast.

Inside the spiny husk there is a seed three times larger than common almonds, very white, tender, juicy, and smooth. These fruit are the most delicate, tasty, and healthy which I have eaten in the Indies. They are sent, as a very valuable thing, from the province of Chachapoyas to the city of Lima, and candied there is not a delicacy that can compare with them.

Where this fruit, so worthy of appreciation, grows, there are many bats which destroy it, because before the husks get hard they eat the heart without detaching the fruit from the tree, so that many times when it is time to harvest them one can find only the empty husks. It is a great shame to think of such soft and delicate fruit, worthy of being enjoyed in the courts of the greatest princes, remaining hidden in deserted mountains, sustenance for such vile animals as bats. (Cobo 1890–1893, 2: 61–62)

The last fruit we will have the sources describe, although there are many more, is the pepino, kachun in Quechua and Solanum muricatum in Latin. It has recently appeared in the exotic fruit sections of the supermarkets.

This is a very well known fruit in Peru, which the Spaniards call pepino de la tierra [native cucumber]; the plant is similar in size and character to that of the eggplant . . . The fruit does not resemble a cucumber in the slightest, unless it be a little bit in size and structure, and therefore I do not know what led the Spaniards to call it pepino de las Indias, except that perhaps they could not find another fruit in Spain that resembled it more closely . . . Truly there is a great variety among pepinos, they differ in size, shape, and color, some are bigger than others, some egg-shaped, some round, and some elongated; some are reddish, others white, yellow, and other colors; but the most common are reddish with stripes of another color, or the same color but darker, along their sides. The skin is a very thin but tough membrane, leathery and peppery, so that it is not usually eaten without peeling, although the fruit may be eaten with the skin as one eats an apple. The flesh is yellow, very watery and sweet . . . It is a very tasty and fragrant fruit, and suitable to refresh oneself during the hot weather, in place of a drink of water; but it is not a delicate fruit that would be esteemed by pampered folk, because it is considered indigestible, for which reason it is not recommended for those with weak stomachs.

The best pepinos grow in the valleys on the coast of Peru. The valleys of Trujillo, Ica, and Chincha are especially famous for them, because they like heat and sandy soil. They have been taken to Mexico, but they do not do well there, because the climate does not suit them. I saw them in the convent of Carmen in the Atrisco valley, and proved to myself that they were tasteless, and without the sweetness which they have in this kingdom. (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 381–383)

Cobo was not the only person to properly appreciate the pepinos that grew in the coastal valleys. The last undisputed Inca emperor, Huaina Capac, traveling along that coast shortly before his death from a pestilence, probably smallpox introduced by the Spaniards but outrunning them, also savored their sweetness.

And they say of him, that traveling in the beautiful valley of the Chayanta, near Chimu, where the city of Trujillo now stands, there was an old Indian in a field, who having heard that the emperor was passing near by, picked three or four pepinos from his field, and took them, and told the emperor “Ancha atunapu micucampa,” which means “Great lord, eat these.” And before the lords and other people he took the pepinos, and eating one of them, said, in front of everybody, to please the old man, “Xuylluy, mizqui cay,” which in our tongue means “They really are very sweet, aren’t they,” which pleased everybody very much. (Cieza de León 1967: 222)

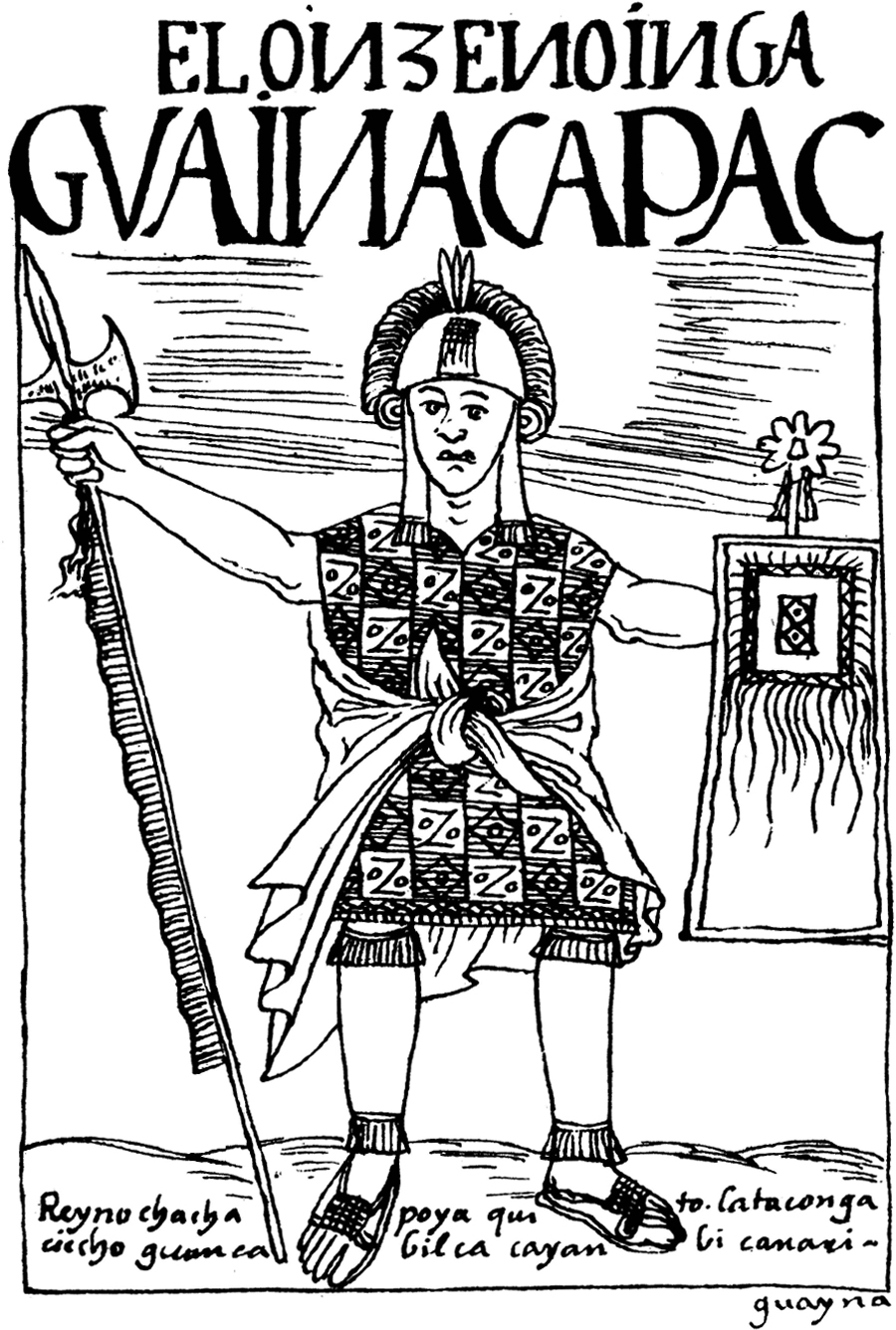

Huaina Capac. From Guaman Poma de Ayala 1936:112.