The Inca

Who was Huaina Capac? He was the ruler of a kingdom which stretched from northern Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, through Peru, and north into Ecuador. He was at the apex of a hierarchy that was supported by a complex system of tributes and warehouses, all meticulously recorded on quipus, great clusters of knotted cords. Much ink has been expended on discussions of whether the Inca state was or was not “socialist.” If a New World civilization can be forced into European categories, it would seem to be more like an empire of accountants. Among the first things that Atahualpa, one of the sons of Huaina Capac who was fighting for the right to wear the royal insignia, said to the Europeans was “We know what you have taken, and where you took it from, and you had better give it all back immediately.” Thirty years after the conquest it was said that it was still possible to account for every grain of maize consumed by the armies of Huaina Capac during his campaigns.

Huaina Capac was a descendant of the sun and of the first Inca, Manco Capac, who emerged from a cave, or perhaps on an island in Lake Titicaca, depending on the version of the Inca origin myth you read.

The first brother was called Manco Capac, and his wife was called Mama Ocllo. They say that he founded the city and called it Cuzco, which in their language means navel, and conquered those nations and taught them to be human, and all the Inca descend from him. The second brother was called Ayar Cachi, the third was called Ayar Uchu, and the fourth was called Ayar Sauca. The word ayar has no meaning in the common language of Peru, it must have had a meaning in the special language of the Inca. The other words are from the common language, cachi means salt, that which we eat, uchu is the condiment which they put in their stews, which the Spaniards call pimiento, the Indians of Peru had no other spices. The other word, sauca, means joy, content, and happiness. (Garcilaso de la Vega 1945, 1: 46–47)

This passage is further explained as the salt standing for the teaching of the Inca, the pimiento (chile) as the taste they got from it, and the happiness as how they lived ever after.

Although these accounts should be read more as fairy tales than as narratives of historical fact, we do have a passage about the food of the first coya, the sister and wife of Manco Capac, and her successors.

Her daily food was usually maize either as locros anca [stew], or mote [boiled maize grains], mixed in various manners with other foods, cooked or otherwise prepared. For us these are coarse and uncouth foods, but for them they were as excellent and savory as the softest and most delicate dishes put on the tables of the rulers and monarchs of our Europe. Her drink was a very delicate chicha, which among them was as highly esteemed as the fine vintage wines of Spain. There were a thousand ways of making this chicha . . . and the maidens of her household took great pains with it. (Murua 1962: 29)

The third coya is said by Guaman Poma de Ayala to have eaten raw maize and ciclla yuyo, an edible herb. However, Murua gives her credit for a more expansive way of life:

She was very fond of banquets and fiestas, and often invited the principal lords of Cuzco . . . giving them splendid food and abundant drink, and they could take home everything they had not eaten. (Murua 1962: 33)

The wife of the fourth Inca had a particular interest in horticulture:

And to sow her fields she chose many special women who took the greatest care of the fields of the finest maize and all sorts of chile, of which the most esteemed and the best was called asnac uchu, meaning fragrant chile. She had a great number of fruit trees, such as tunas [cactus fruit], guabas, plátanos [plantains], pacayes, and all the other kinds and varieties that grow in these provinces. (Murua 1962: 36)

The author is mistaken when he includes plantains in the inventory of this garden. Many early European chroniclers thought that bananas and plantains (Musa spp.) were native to the New World. This has been endlessly repeated by later authors, but although Musa species spread far and fast in the New World, they came to the Americas with the Europeans from the Canary Islands and ultimately from New Guinea.

The fifth coya:

She bathed twice each day, and always ate alone. The table was carved, and three or four feet long, the tablecloth and napkins were colored. (Murua 1962: 38)

The wife of the sixth Inca had a thousand Indians as attendants, all of whom ate from the royal storehouse. She also had a thousand, or some say three thousand, waiting women, who presumably also ate from the inexhaustible granaries. It was either her son or the son of the sixth Inca by some other wife who conquered the eastern slope of the Andes and brought back coca (Erythroxylum coca). While not a foodstuff strictly speaking, coca was of such importance in Inca culture that it is worth a few words. Originally its use was restricted to the nobility for religious purposes, including funerary offerings. The leaf is described by Cobo as like a lemon leaf, and after a complicated curing process, a wad of it was put in the mouth, with a bit of lime from burned limestone or seashells. The leaves were not chewed, but the juice was swallowed. Oddly, Pedro Pizarro was told by two high-ranking Inca that it did not have the effect it was claimed to have:

. . . while they made others gather coca, which is an herb they carry in their mouths, which they prize highly, and use for their sacrifices and idolatries, and this coca does not keep them from thirst, or hunger, or exhaustion, even though they say it does. So I was told by Atahualpa and Manco Inca. (Pedro Pizarro 1978:96)

Dr. Abraham Cowley, a seventeenth-century English poet engaged in the integration of New World plants into Old World mythology, was convinced of its invigorating qualities, whether or not he ever used the plant or even laid eyes on it.

Mov’d with his Country’s coming Fate (whose Soil

Must for her Treasures be exposed to spoil)

Our Varicocha first this Coca sent,

Endow’d with leaves of wond’rous Nourishment,

Whose Juice Succ’d in, and to the Stomach tak’n

Long Hunger and long Labour can sustain;

From which our faint and weary bodies find

More Succor, more they cheer the drooping Mind,

Than can your Bacchus and your Ceres join’d.

. . .

Nor Coca only useful art at Home,

A famous Merchandize thou art become;

A thousand Paci and Vicugni groan

Yearly beneath thy Loads, and for thy sake alone

The spacious World’s to us by Commerce Known. (Cowley in Mortimer 1901: 26–27)

Today coca is still involved in commerce throughout the “spacious world,” but it is in the unfortunate form of cocaine. That coca was not altogether benevolent even as used aboriginally is substantiated by the description of the eighth coya:

She ate many dishes, and was also addicted to coca, coca was a vice with her, while she slept she had it in her mouth. (Guaman Poma de Ayala 1980, 1: 113)

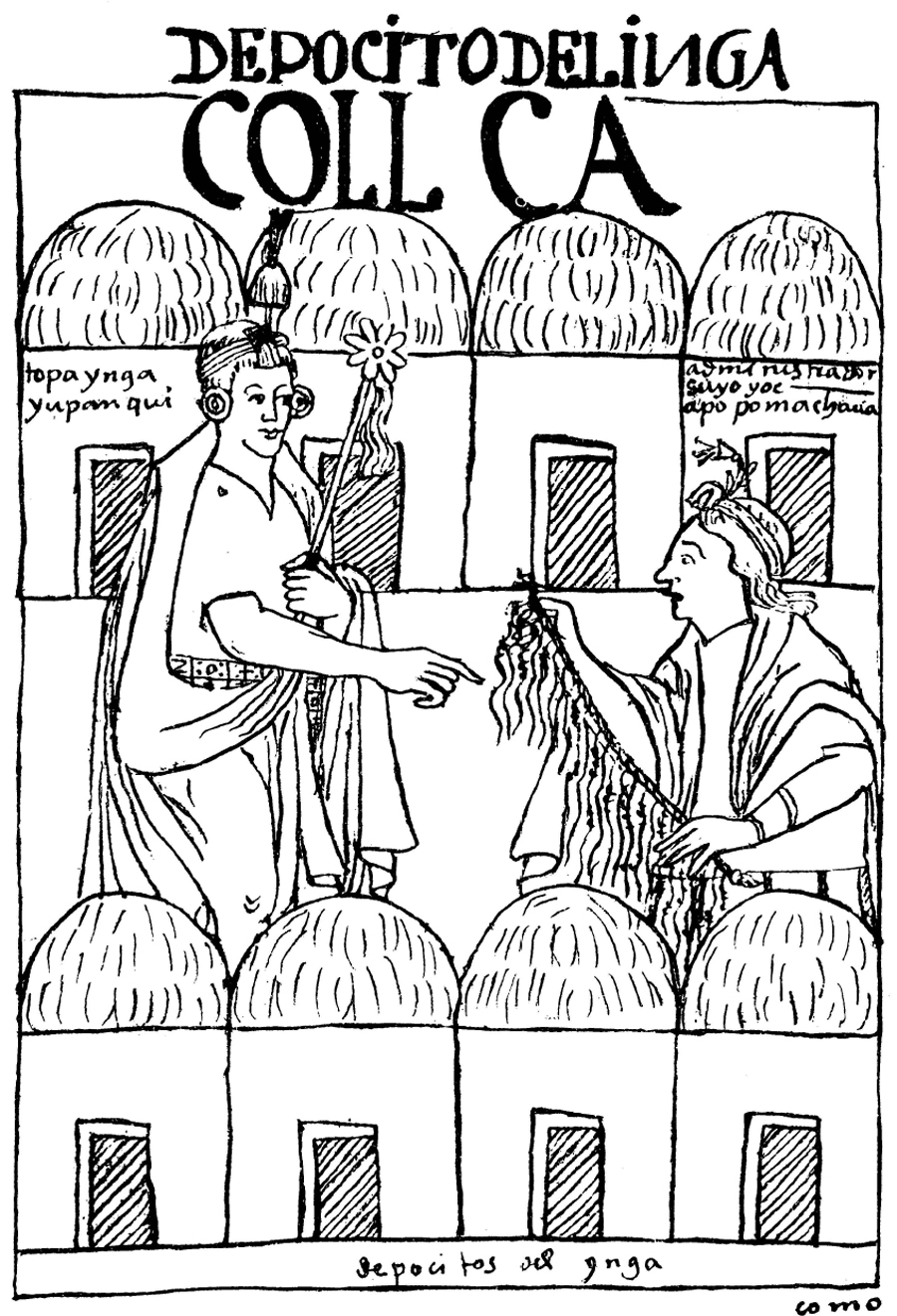

One of the several Inca Yupanquis, presumably her father and father-in-law, is said to have founded the system of warehouses and established the redistribution network of the Inca state.

He ordered that all the lords and chiefs who were there would meet in his house on a certain day, and when they had come together as he had ordered, and being in his house, he told them that it was necessary that there be in the city of Cuzco warehouses of all the foodstuffs: maize, chile, beans, tarwi, chichas, quinoa, and dried meat, and all the other provisions and preserved foods that they have, and therefore it was necessary that he order them to bring them from their lands. And then Inca Yupanqui showed them certain slopes and mountainsides around the city of Cuzco and visible from it and ordered them to build granaries there, so that when the food was brought there would be somewhere to put it. And the lords went to the sites that the Inca showed them, and got to work, and built the granaries. And it took them five years to build them and divide the lands, because there were so many granaries to build, as was ordered by Inca Yupanqui, so that they would hold much food, and there would be no lack of them. And with that supply of food he wanted to build the city of Cuzco of masonry and shore up the gullies surrounding it, and he thought that having supplies in such quantity that they would never lack, he could put as many men as he wished to building and rebuilding the public buildings and the houses. (Betanzos 1968: 35)

Once the granaries were built and stocked the distributions could begin.

And he had divided among them maize, and dry meat, and dry fish, and llamas . . . and dishes to use, and everything else he thought necessary for their housekeeping. And he commanded that every four days they give and share out among everybody in Cuzco what each one needed of food and provisions . . . ordering that the food and provisions be taken out of the granaries and put on the plaza of the city in great heaps . . . and that from there they be divided by measure and number and reason, giving each what he needed . . . and thus from the time of Inca Yupanqui this foresight and beneficence continued until the Indians were subjugated by the Spaniards, with whose arrival all this ceased and was lost. (Betanzos 1968:40)

Inca laws commanded not only storage and distribution but what should be grown, what should be eaten, and how it should be treated.

We command that there be an abundance of food throughout the kingdom, and that they plant very much maize, potatoes, and ocas; and make caui, kaya, chuño, and tamos [different preserved roots], and chochoca [maize lightly boiled and sun-dried]; and quinoa, ulluco, and masua [Chenopodium quinoa, Ullucus tuberosus, and Tropaeolum tuberosum, respectively]. That they dry all the foods including yuyos [greens] so that there will be food to eat all year round, and that they plant communally . . . maize, potatoes, chile, magno [greens to dry] . . . Let them make up the accounts each year, if this is not done the tocricoc [royal official] will be cruelly punished in this kingdom.

We command that nobody spill maize, or other foods, or potatoes, nor peel them, because if they had understanding they would weep while being peeled, therefore do not peel them, on pain of punishment. (Guaman Poma de Ayala 1980, 1:164)

That they observe the fields to see which plant or seed does the best, and plant nothing but the best seed there, without mixing it with others; here grains, there beans, here cotton, there chiles, here roots, and there fruits, and this way for all the rest. (Anon. 1968: 178)

They did not have the right to eat whatever they wanted but what the Inca felt they should eat. (Cobo 1979: 240)

This system of collection and distribution greatly impressed at least some of the Europeans.

No thinking man there can be that does not admire such an admirable and provident government, because being neither religious, nor Christian, the Indians in their own manner reached this high perfection, having nothing of their own, yet providing everything necessary to everybody, and sustaining so generously the things of religion, and those of their lord and master. (Acosta 1954:196)

Mythological history credits the ninth Inca, Pachacuti, with instituting banquets as part of the redistribution system. The archaeological evidence for them exists, although the process was probably not simple and straightforward. When Thompson and Morris (1985) investigated the ruins of Huánuco Pampa, they found that the large structures around the main square were not, as they had thought, to house Inca bureaucrats. They were full of cooking debris because they were places to prepare, serve, and in case of bad weather consume the redistribution banquets Pachacuti is supposed to have started.

This lord introduced another laudable custom, which resembles the simplicity of the ancients. This was that everybody should eat in the plazas, and as the originator of the custom he was the one that most used it. As the sun rose he emerged from his palace and went to the plaza: if it was cold they made a great fire, and if it rained there was a great house suitable to the settlement that they were in. After a brief time for chatting, and as the usual meal hour approached, the wives of all who were there came with their food in their little jars, already cooked, and a little container of wine on their backs, and if the lord was there they began with serving him, and then they served the rest. Each one was served and given to eat by his wife, and the lord the same, even if he was the Inca himself, who was served by the queen, his principal wife, with the first dishes and the first drinks, the rest of the serving was done by the male and female servants. Each woman sat back to back with her husband, she served him all the rest, and then starting with the first dish she ate of what she had brought in her separate place, being, as I have said, back to back.

One invited the other to share what he had, and got up to serve him with it, drink as well as food. They never drank until they had finished eating. They invited each other to drink, each inviting his friend, and if someone invited the lord to drink, the lord took it from his hand and drank with good will.

With the meal finished, if it was a fiesta day they sang and danced and spent the whole day amusing themselves, but if it was a working day they all went off to their place of work.

They did this every day for their morning meal, which was the main meal. At night each dined in his house on what he had, and they never ate more than twice a day, and the morning meal was the main one.

They all ate on the ground seated on some mats, and they ate a diversity of dishes, all with chile, green or red; and just a bit of everything, because all of what they prepared for their meals was almost nothing. Nobody had to watch other people eating who had nothing himself, because as I have said, nowhere in the world do they share so with those who have not, and they say that we Christians are bad people because we eat alone and invite nobody, and they laugh at us when we offer to invite someone, saying that they invite in truth and in deed, not just words. They, even if they have nothing but a grain of maize, must share willingly, sometimes forcing those who refuse, when they see that they have little, to take it. (Las Casas 1958: 667–668)

There are other accounts which give slightly different pictures of these meals, but they remain a means of redistributing the contents of the warehouses.

They had sumptuary laws, which forbade luxury in everyday dress, and expensive things like gold, silver, and precious stones, and completely did away with excess in banquets and meals. And it was ordered that two or three times a month the inhabitants of each settlement should eat in the presence of their chiefs, and perform military or secular games, to reconcile enmities and keep the peace, and so that herdsmen and other workers in the fields would be encouraged and supported. The law on what they called the poor ordered that the blind, mute, crippled, maimed, decrepit old men and women, the chronically ill, and all others who could not work the soil for their food and clothing be fed from the public storehouses. There was also a law that commanded that the same public storehouses provide for guests. The foreigners, the pilgrims, and the travelers, for all these there were public accommodations which we call corpahuaci, which means inn, where they were given all that was necessary and did not have to pay anything. (Blas Valera in Porras Barrenechea 1986:466)

The tenth Inca was Topa Inca:

In the morning he ate, and from midday into the afternoon he held audiences, surrounded by his guard, with those who wished to speak to him. The rest of the time, into the night, he spent drinking, and then supped by the light of wood fires, because they used neither fat nor wax [for lighting], although they had plenty of both. (Cieza de León 1967:192)

Topa Inca is supposed to have started the system of chasquis, the post houses and messengers which, combined with the excellence of the Inca roads and bridges, gave them a system of communication unrivaled in the New World. Unfortunately many authors think that this system was in use all over the New World, so we get many references to runners providing Motecuhzoma with ocean-fresh fish in his capital of Tenochtitlan, whereas the ruler actually being provided with fresh fish was the Inca in Cuzco, thousands of miles and a continent away.

This kind of mail, which in Peru are called chasquis, are certain Indians put on the road by order of the neighboring towns, as far apart as three crossbow shots, more or less, depending on the character of the country. The chiefs were obliged, under threat of the most severe punishment, to support them in these places, changing from month to month, or as they saw fit. There were two of them in huts or shelters erected for their use, ready to go at any time, and the news they had to carry or the message they had to take went from mouth to mouth, so that when one of the chasquis was close enough so that the other could hear his voice, he began to repeat his message, and the other learned it so carefully that not one word or syllable or letter was forgotten, and when the runner arrived the other had learned the message, and the newly informed ran until he came to the next station and repeated the process, and so on and on, and in this manner it was admirable how quickly news traveled two and three hundred leagues, and not only news was carried in this fashion but presents and important tributes. (Cabello Valboa 1951: 424–425)

And when the Inca wished to eat fish fresh from the sea, and as it was seventy or eighty leagues from the coast to Cuzco . . . they were brought alive and twitching, which seems incredible over such a long distance over such rough and craggy roads, and they ran on foot and not on horseback, because they never had horses until the Spaniards came to this country. (Murua 1962, 2:47)

The runners were specially selected and trained, and Murua claims that in training they were fed only hamca, toasted maize, once a day and allowed to drink once a day. On the job, however, their supplies included water, maize, chile, charqui, “partridges,” cuys, and chicha, with fruit if available from nearby valleys—guabas, avocados, pacayes, and passion fruit.

Auditing the accounts at the state warehouses. From Guaman Poma de Ayala 1936: 335.

The eleventh coya “believed in working every day, daily she fed two hundred poor people . . . and she also fed the lords and princes, five hundred men of this kingdom” (Guaman Poma de Ayala 1980, 1: 119). She was the wife of Huaina Capac, the Inca in the episode of the old man and the pepino. The fact of her working is not unusual. It is said that even the Inca hoed his own garden, in order to set a good example and to show that nobody was so rich that he could afford to insult the poor.

Huaina Capac is on the border of Western recorded history. Toward the end of his reign the Europeans were probing the northern coasts of his dominions. Guaman Poma de Ayala says that one of the two Europeans left behind on the coast during a reconnaissance expedition was brought to Huaina Capac in Quito, and Huaina Capac asked him, presumably in some sort of sign language, what he ate. The European answered, presumably also using signs, that he ate gold and silver. The Huaina Capac of the story should have locked him up for a few weeks with lots of gold and silver but no food or water. Instead he loaded him down with riches, and the European returned to his own country a rich man. Another version of this tale is that while Huaina Capac did indeed wish to see a specimen of the curious beings who had landed on his coast, they were killed before they got to him, to his great displeasure.

The only information we have about his food habits concerns his chicha drinking. The word for chicha that he would have recognized would have been something like asua. The Europeans replaced the Quechua word with the Taino chicha, which they had learned in the Antilles.

The Indians say that he was a great friend of the poor, and ordered that especial care be taken of them in all his dominions. They say he was very affable with his people, yet grave. They say that he drank more than three Indians put together, but nobody ever saw him drunk; and when his captains and great lords asked him how he could drink so much and not get drunk, he said he was drinking for the poor, because he was much concerned with their sustenance. (Pizarro 1978: 49)

Chicha was a major part of Inca life, important in ritual and religion as well as a source of nourishment. However, European writings on the subject must be read with the same sort of caution that one uses with the European sources on Mexican cannibalism. What was the writer trying to prove? Was he justifying the enslavement of the Indians by making them less than human and dwelling on their disgusting and depraved habits? Is the subject under discussion linked to idolatry and therefore to be painted in the darkest colors, because it stands in the way of the triumph of Christianity? Or was the author convinced that the American Indian was the repository of virtues and customs that had abandoned Europe with the end of the golden age? Most of the colonial sources should be treated as advocates of one of these points of view or another, and we must never forget the silent, shadowy figures of the Indians, whose evidence survives filtered through their conquerors and descendants, if at all.

Firstly, drunkenness and intemperance in drinking was a passion with this people, the source of all their ills, and even their idolatry. This vice exempted neither dignity nor status. At the beginning, when they settled in the country, for a long time they had no wine, only cold water, and they say that at that time they had no vices, and were not given to idolatry. Then they tried to find something that was better for them to drink than the water of that country, because, if you look into it, you will see that certain provinces have water so thin that it corrupts, and in others it is so thick that it makes for vascosidades and stones. On the coast most of the water you drink is brackish, more or less, and it is usually warm, as the Spaniards there know . . . So to remedy this, and to free themselves from sickness, they invented wine made from maize, which if it is pure refreshes the digestive system and the liver . . . The doctors ordered that for the wine to have the desirable effect of flushing the bladder and dissolving stones, the maize should be mixed with human saliva, which is very medicinal. From this came the chewing of maize by children and young maidens, and once chewed it was put into cups, so that afterwards it could be cooked, and strained through various strainers of cotton cloth, with clean water, and the liquid that comes through all this is the wine, and it has been used for a long time. As it is medicinal there is no reason to be disgusted about the maize being chewed, because for reasons of health today people take all sorts of horrible things, like dog feces, urine, and other disgusting things, and in comparison to them human saliva is very clean. And when our wine is put on the table we do not remember that it has been trodden out and pressed by people’s dirty and dusty feet.

This wine, which had been made in Peru from the most ancient times as a medicine, then became a delicacy and a drink to celebrate festivals with . . . Thus the days of triumph for victories won, the days of plowing the earth, the days of planting the maize, of reaping and harvest, those of Aymoray, which is taking the grain to the troxe and storehouse, it was open to everybody to drink as much as they wanted. The exceptions were the boys and girls, the temple priests, the vestal virgins, the king’s guard, the soldiers of the fortress, the judges, the weekly workers, the women who had to attend to the services of the house, the plebeians, and the craftsmen. They spent the whole day drinking, and having digested the wine they gave permission for the next day for all who had not drunk on the first day, except for the vestal virgins, and the priests of the idols, to whom it was never permitted. For the guards and the garrison of the fortresses they substituted other soldiers who had drunk the day before. This was common usage for their festivals, at the time of plowing and planting and reaping and taking the maize to the troxe, because first they did the work they had to do, finishing it in every respect, and then began the invitations and the banquets. At the banquets the food was very scanty, one of us could barely live on what five of them ate. But the drinking made up for it, because chicha is a true potation, providing as much nourishment as solid food, almost in the same fashion as chocolate in Mexico. (Anon. 1968: 174)

The idea of chicha as more than just a drink is also brought out by Fernando de Santillan in his description of the situation after the conquest.

Their food is maize and chile and greens, they never eat meat or anything of substance, except for some fish for those who are near the coast, and for this reason they are so fond of drinking chicha, because it fills their bellies and nourishes them, and if it does not befuddle them it is very nourishing, which is not true of the one called sora, which is very strong and takes away their judgment. (Santillan 1879: 77)

The refusal of the aborigines to drink plain water was something that struck the chroniclers over and over again, coming as they did from the Mediterranean, where the connoisseurship of the taste of various springs and fountains has been a branch of knowledge at least since classical antiquity.

They are great enemies of water, and never drink plain water unless there is a lack of other drinks, and there is no greater torture for them than to make them drink it, a punishment which the Spaniards inflict on them occasionally, and which they feel more than blows. (Cobo 1890–1893, 3: 35)

Under the name of chicha we include all the drinks that the inhabitants of this New World use in place of wine, and which they frequently use to make themselves drunk. They are so inclined toward this vice that neither their conversion to our holy faith, nor their dealings and connections with the Spaniards, nor the punishments inflicted on them by their priests and judges, will discourage them from it, although in some provinces there is some improvement, and in general the drinking bouts are nowhere as frequent as they used to be in the time of their paganism. Chicha is made of many things, each nation using the fruits and seeds that their country produces in the greatest abundance. Some chichas are made of ocas, yucas, and other roots, others of quinoa, and the fruits of the molle. The Indians of Tucumán make it of algarrobas, those of Chile of strawberries, those of Tierra Firme of pineapples, the Mexicans make the wine they call pulque from maguey, and thus in this fashion the different regions use different fruits and vegetables, and there seems to be a conspiracy of the inhabitants of America against water, because they refuse to drink it pure. The best chicha of all, and that most commonly drunk in this country, that which holds the first place as a precious wine before all the other drinks of the Indians, is that which is made of maize. This is made in many ways, and the differences are that some chichas are stronger than others, and of different colors, because chicha is made red, white, yellow, gray, and other colors as well. A very strong one is called sora, which is made of maize which has been buried for a few days until it sprouts; another is made of toasted maize; another of chewed maize; and there are other variations as well. The one most commonly drunk by the Indians of Peru is made of chewed maize, and because of this one sees, not only in the native villages, but in Spanish towns where there are many Indians, such as Potosi, Oruro, and others, little groups of old women and boys sitting and chewing maize. It disgusts the Spaniards not a little even to see this, but it does not bother the Indians to drink something made so filthily. They do not chew all the maize of which the chicha is made, but only part of it, which, mixed with the rest, acts as yeast. The Indians think this so necessary to give the right finish to the chicha, that when the maize is ground in our watermills they chew the flour in their mouths until it is dampened and made into dough, and those who make it their business to chew maize or flour take their pay by swallowing as much as they need to assuage their hunger. (Cobo 1890–1893, 1: 347–348)

Cobo is of course mistaken that the chewed maize acts as yeast. It is the action of the enzymes in human saliva that produces the desirable effect.

“We eat gold.” From Guamam Poma de Ayala 1936: 369.

One of many special chichas made for the Inca was supposed to be extra smooth because it was aged for a month. Certain coastal valleys were renowned for their vintages:

As soon as you leave Trujillo you enter the Guañape valley, which is seven leagues toward Lima, which was as famous among the aborigines in times past for the chicha which was made there, as Madrigal, or San Martin in Castile, for the good wine which they produce. (Cieza de León n.d.: 366)

An elaborate etiquette grew up around chicha drinking, as well as all sorts of technology having to do with the drinking itself.

Because you must know that there was a custom, and a sign of good breeding, among these lords and all others of that country, which is that when a lord or lady goes to the house of another, to visit them, or see them, they must take . . . a jar of chicha, and coming to the place of the lord or lady they are going to visit they pour the chicha into two cups, and one is drunk by the person who visits, and the other drinks the chicha given him, and thus they both drink. The same is done by him who is being visited, who has to get two other cups of chicha, and give one to the visitor, and drink the other one. This is done between lords, and it is the greatest honor they have, and if this is not done when they visit, the person visiting thinks they are insulted if not given to drink, and no longer visits the person, and in the same way the person who gives a drink to another who refuses it thinks themselves insulted also. (Betanzos 1968: 55)

This pleasant social custom could lead to melodramatic scenes.

And thus that day they celebrated the peace, all eating together, which is to say on a plaza, facing each other. Once the meal was finished, the chief arose and took two vessels of his drink to toast his new friend, as was the common custom of the Indians. He had one vessel poisoned to kill him, and when he came opposite the other chief, he invited him to drink from it. The one invited had either changed his opinion of the one who had invited him, or was not satisfied enough to trust him and suspected what was going on. He said “Give me the other vessel and you drink this one.” The chief, so as not to show himself a coward, quickly switched hands, and gave his enemy the innocent vessel, and drank the deadly one. Within a few hours he had died, as much from the strength of the poison as from the rage of seeing that by wishing to kill his enemy he had killed himself. (Garcilaso de la Vega 1945, 1: 170)

The vessels used for all this drinking were of many materials. The Europeans found the gold and silver ones most interesting, but there were also elaborately painted wooden ones called keros, and trick vessels that made strange sounds and led the chicha on a circuitous path before it got to its destination.

And I saw the head with the skin, the dry flesh with the hair, and it had the teeth clenched, and there was a silver tube there, and there was a big gold cup attached to the top of the head, which Atahualpa drank from when he remembered the wars his brother had made against him. He put chicha in the big cup, and it came out of the mouth and the tube, from which he drank. (Cristóbal de Mena in Biblioteca Peruana 1968:152)

Making chicha cups out of the skulls of defeated rivals must have been a regular and expected practice if one is to take this story of Atahualpa during his captivity seriously.

He was laughing one day, and looking at him the Governor Pizarro asked him what he was laughing about, and he said, “I will tell you, sir, that my brother Huascar said he was going to drink out of my skull. They have brought me his skull to drink out of and I have done so, you will drink out of his skull and out of mine. I thought there were not enough people in the whole world to conquer me, but you with one hundred Spaniards have captured me, and put to death a large part of my people.” (Molina 1943: 46)

A self-righteous shudder by Europe-centered readers is out of place here.

Nicephorus [Emperor of Byzantium] set out for Bulgaria [in A.D. 811] with a formidable array of troops . . . As soon as he saw them Krum [the Bulgarian Khan] sued for peace, but Nicephorus ignored Krum’s offer, easily took possession of Pliska and the Bulgarian palace, and again refused to discuss terms. This time, however, the Bulgarians sealed off the passes leading out of the mountain defile in which the Byzantine army had carelessly encamped . . . They then swooped down upon the trapped Byzantines and butchered the entire force, including the Emperor and many of his chief officers. Krum cut off the Emperor’s head, and after exhibiting it on a stake for several days, had the skull covered with silver and used it as a drinking bowl. (Anastos 1966: 94)

No matter what type of container held the brew, drinking it appears to have been as tightly regulated as everything else was in the Inca empire.

That they be moderate and temperate in their eating, and more so in their drinking, and if somebody gets so drunk that they lose their judgment, if it is the first time they are punished as the judge shall decide, for the second offense exiled, and for the third deprived of their offices if they are magistrates, and sent to the mines. In the beginning this law was rigorously observed, but later it was so relaxed that the ministers of justice were those who drank the most, and got drunk, and there was no punishment. The amautas, who were their scholars and wisemen, interpreted the law as making a distinction between cenca, which is to become heated, and hatun machan, which is to drink until you have lost your judgment. The latter was what usually happened, but they ignored the follies of the madmen, and little or nothing happened to them. (Anon. 1968: 178)

The last word on Inca drinking should be given to Miguel de Estete, who was one of the 168 Spaniards who captured Atahualpa in 1532. His words, those of his companions Pedro Sancho and Francisco de Xerez, Pedro Pizarro and Cristóbal de Molina of Santiago (both of whom wrote many years later), letters written for the illiterate Francisco Pizarro, and a few letters from the religious on the expedition, Vincente de Valverde, are the only eyewitness reports we have.

Everybody placed according to their rank, from eight in the morning until nightfall, they were there without leaving the feast, there they ate and drank . . . because even though what they drank was of roots and maize and like beer, it was enough to make them drunk, because they were people of small capacity. There were so many people, and such good drinkers, both men and women, and they poured so much into their skins, because they are good at drinking rather than eating, that it is certain, without any doubt, that two broad channels, more than half a vara [vara = .84 m] wide, which went under the paving to the river, which must have been made for cleanliness and to drain the rain which fell in the plaza; or possibly for this same purpose, ran all day with urine, from those who urinated in it; in such abundance as if there were fountains playing there; certainly matching the quantity that was drunk. Considering the number of people drinking it was not to be marveled at, but to see it was a thing unique and amazing. (Estete 1924: 55)

As with his near contemporary Motecuhzoma, the death of Huaina Capac and the destruction of his empire were supposedly foretold by mysterious portents. There was a green light in the sky before Huaina Capac died, and when he saw the same light some five and a half years later, his son Atahualpa correctly predicted his own death. According to Pedro Pizarro, Huaina Capac was fasting (which meant that he was abstaining from salt, chile, chicha, and women) when three very small Indians, dwarves, entered the room where he was in seclusion. They said that they had come to call him, but we do not know what for. Nobody else saw them, and they vanished as mysteriously as they had come. Still more eerie, although reminiscent of Pandora’s box, is the omen reported by Joan de Santacruz Pachacuti Yamqui (1968: 311), who tells of a black-cloaked messenger delivering a box to the Inca. Told to open it the messenger refused, telling the Inca that he must do it for himself. When the box was opened the contents came fluttering out, like butterflies or bits of paper. It was the smallpox. Within a few days people began to die, and soon Huaina Capac was among them. Even the fact that some of the oracles gave the wrong advice was interpreted as an evil omen. The great oracle of Pachacamac, not far from Lima, the present capital of Peru, said that the ailing Inca should be taken outside so that the rays of his deity and ancestor, the sun, could shine on him and cure him. The oracle’s prescription was followed, but the sun’s rays killed rather than cured. The oracles in Purima, twelve leagues outside of Cuzco, are said to have told the people that bearded men were coming to conquer them and they had better eat, drink, and spend all they had so that there would be nothing left for the conquerors. As in Mexico there was supposed to have been a myth about gods, Viracochas in the Peruvian case, who had sailed away across the seas. When the Europeans arrived from the sea they were considered to be the Viracochas returning. Calancha says that this identification became even more certain when the Europeans showed their true character, their ferocity and inhumanity making it obvious that they were gods and not men (Calancha 1974, 1: 245). As usual, such “predictions” smell more of Spanish policy than aboriginal prescience.

Before his death, Huaina Capac called . . . his vassals, captains, chiefs, and nobles, and told them that he knew from his oracles that the twelfth king of this country would be the last, and that he was the twelfth king of this country, and that after his death they must expect other lords who were going to subjugate that country, who would be unknown people, soon to appear, who would destroy the inhabitants, and put a stop to their religion and cult of idols, and he told them, “Pay attention that I command you to serve and obey those people, because their rule will be better than ours, nobody should take up arms against those people, but give them help, tribute, and gifts.” (Calancha 1974, 1: 234)

Huaina Capac, whether or not he actually believed that he was fated to be the twelfth and last Inca, did lay the foundation for the civil war that was raging in his empire when the Europeans arrived. The son he had named as his successor at his death in 1527 had died before he could ascend the throne, and there was no order of succession beyond the named heir. The claimants to the imperial fringe were two other sons: Huascar, a son by the principal wife, and Atahualpa, a son by a lady of Quito. The five years between the death of Huaina Capac and the arrival of the Europeans were ones of continuous warfare. How the Inca empire might have developed had things run their course without foreign intervention will forever remain unknown, just as we will never know what might have happened had the Europeans chanced upon an Inca empire united.