“The Word became flesh and lived among us.”

– THE GOSPEL OF JOHN

One reason why the topic of this book is controversial is because it implies that Jesus had a sexual identity. I think that many people view Jesus as a prototype for celibate priests. Many assume that Jesus chose celibacy for the same reason that priests take vows of celibacy. Sex is so commonly associated with naughtiness that it is difficult to think of it in terms of godliness. But, in our heart of hearts, we know that sex isn’t sinful. So why is it so difficult to imagine a fully human Jesus who was married?

Could it be because we’re projecting our own sexual hang-ups onto Jesus? Could it be that when we imagine Jesus with a sexual identity, we can’t help but imagine a Jesus with the same sorts of hang-ups? Imagining a married Jesus feels a bit like we’re defrocking Jesus – as if we’re accusing him of failing to keep his vows.

But what if we think of Jesus not as a prototype for priests, but as an archetype for humanity? Indeed, at least for us Westerners, Jesus is an archetype. In this case, to say that Jesus is an “archetype” means that we use our ideas about him to create images of nobility, purity, and redemption. Put another way, our ideas about Jesus create a standard by which we measure our own nobility, purity, and redemption. Like it or not, this is the place that Jesus occupies in the Christianized West.

This is where things get tricky: if Jesus isn’t sexual, how can we imagine our own sexual identities in noble, pure, and redemptive terms? If Jesus, the standard of nobility, is devoid of sexuality, how can we avoid feeling naughty? Could it be that we’ve created a non-sexual Jesus because of our own insecurities? Conversely, could it be that our continued insecurities have reinforced our image of a non-sexual Jesus?

WE’RE COMPLICATED

We Westerners are preoccupied with sex. Language can be a very important window into a culture. When something is interesting, we say it’s “sexy.” “Sex sells” is one of the mantras of democratic capitalism. One of our favorite storylines is “boy gets girl.” Indeed, some of our most celebrated heroes are sexual conquerors of some sort: Rocky Balboa, James Bond, Robin Hood, Captain Kirk, Romeo, Superman, almost any film with John Wayne – the list could go on and on.

A dialogue from the HBO comedy series Bored to Death illustrates this idea of Western heroism. In the following scene a boyish, thirtysomething, would-be gumshoe is talking with a younger woman at a party:

Her: “But are you a boy or a man?”

Him: “A man … [hesitates] what’s the difference?”

Her: “With a man, it’s like he’s taking you and you like it. With a boy it’s like he’s stealing something from you and you don’t like it.”

There are several levels of absurdity in this exchange, but I’ll only point to one. Here we see that the woman is the conquest. It’s not that she is a partner in the hero’s journey; she is the boon, the object that the boy can claim to make him a hero.

Of course, we can think of exceptions. For example, in the Coen brother’s film The Big Lebowski, the hero is all but disinterested in becoming a sexual conqueror. Consider this portrait from the script:

“And I’m talkin’ about The Dude here … even if he’s a lazy man, and The Dude was certainly that – quite possibly the laziest man in Los Angeles County, which would place him high in the running for the laziest worldwide …”1

But this is the exception that proves the rule; “The Dude” is entertaining because of his utter lack of drive. More often than not, we want our heroes to be conquerors, and this is commonly shown as sexual conquest.

The flip side of this coin is that we Westerners are terrified of sex. Sexuality is on display in almost every kind of media and, ironically, it is a source of shame for us. It is often difficult for us to talk about sex intergenerationally. Sometimes we even have trouble talking about sex with our sexual partners. We have very few sacred rites of passage to nurture our children to maturity. We fear the idea of our children maturing because we fear how they might explore their sexual identities.

Worse, we tend to forbid or problematize language that speaks to sex directly. This is another way that language provides a window into our culture. For good or ill, the heroes of our favorite narratives communicate our ideals and aspirations for us. This is not to sermonize against art; it is just an observation of our cultural complexity. Because we refuse to talk about sex directly, we give the image of James Bond more power by default.2

In my view, the loss of tradition that infuses sexuality with sacred significance is a problem. The heroes of popular culture have reinforced the myth of conquest that dehumanizes women. At the same time, the traditionally religious voices have lost almost all credibility in public discourse. For example, the Catholic Church has lost considerable ground on topics related to sexual norms (especially in recent years). But many still long for a religious institution with a long view. Many, including me, like the idea of an institution that isn’t blown over by every passing inclination of popular culture. I like the idea of sacred rites of passage that help us pass down sacraments from generation to generation. I don’t want my children to fear sex or pretend to be non-sexual, nor do I want them to buy into the myth of sexual conquest.

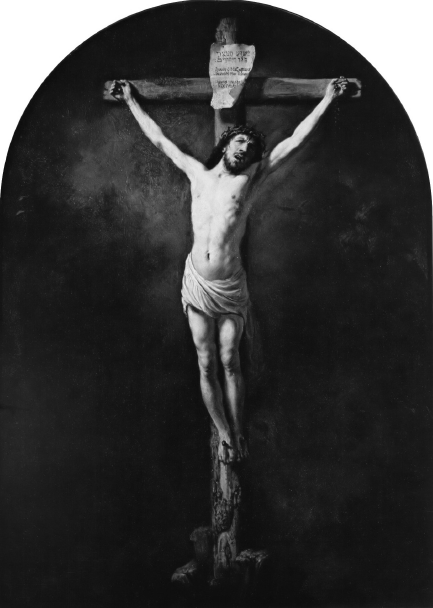

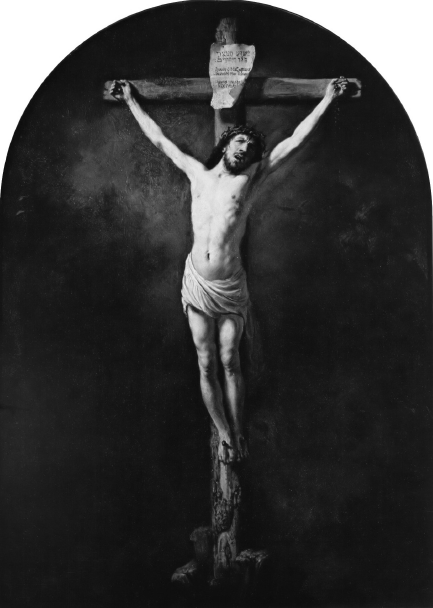

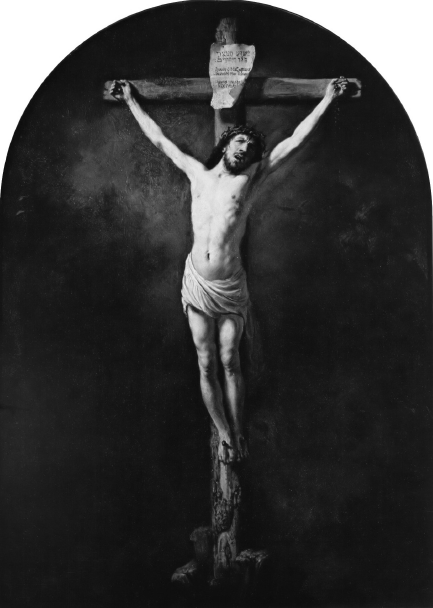

The Church has traditionally championed a Jesus who isn’t conquest-oriented. The history of Christianity has been a story of conquest in many ways; but the image of the defeated Jesus, hung on a Roman cross as a willing and altruistic sacrifice is a different type of hero. For this subversive image I am grateful to Catholicism and I am reluctant to let go of the image. But the traditionally non-sexual, celibate portrait of Jesus works hand-in-glove with this image. In Western iconography, Jesus is not a conquistador. Images of him that suggest otherwise are intriguing because they are novel. But, at the end of the day, would a married Jesus really destroy this image? Must sexuality always be about our imperfections?

Christianity has both contributed to and critiqued our popular views of sexuality in the West. This is important to recognize because the discussion of a married Jesus will have consequences. Psychologist and theological theorist Hal Childs writes that we quest for Jesus’ personality to see our collective, psychological “reflection at the bottom of the well.”3 Saying anything “new” about Jesus reveals something about us. According to Childs, Jesus reflects the face of God to us; at the same time, Jesus reflects our own humanity back to us. In art, religion, indeed Western culture at large, Jesus is the portrait of complete and authentic humanity. And yet he represents a humanity that is devoid of sexuality. Something is amiss.

Perhaps, when it comes to sexuality, Jesus is a hero that reflects our innocence, and we are reluctant to see him as fully human. A married Jesus will have consequences on several levels because of how important he has become in defining our sexual norms and values. In my opinion, we really don’t need a James Bond type of Jesus. Perhaps we need – as the Church has always known – a fully human Jesus. At the same time, we should be wary of inventing a sexuality for Jesus simply because we want to assuage our own insecurities.

THE EMERGENCE OF ASCETIC RELIGION

Jesus was a first-century, Jewish Galilean. It is probable that he did not come from a well-educated or cosmopolitan family.4 Many of his views about sex and family would have been informed by deeply rooted traditions and by rural rabbis. While this provides us with a starting point, it does not tell us everything we need to know about Jesus. A large part of being Jewish involves negotiating with non-Jewish religions and cultures. This has been true throughout the history of Judaism and was certainly true during the time of Jesus.

Long before Jesus walked the Earth, and the Apostle Paul wrote his letters, Alexander the Great ruled from Egypt to Pakistan. Greek language, philosophy, sports, politics, and culture more generally seeped through the cracks of thousands of clans. Greek culture in Alexander’s empire was much like capitalism is today in our “global” economy. There are a few standard ways of thinking, and a thousand different adaptations.

One of the more common ideas during the period of Greek domination was that gods could be and often were sexual beings. This was a notion that the Greeks probably borrowed from the Egyptians. Fertility is fundamental for life, and thus sexuality is fundamental for human life. We see this idea reflected in Egyptian mythology, Greek mythology, and Roman mythology. The sexuality of gods wasn’t just a quirky or obscure notion. This idea was commonplace in the history of Western culture from before 3000 B.C.E. and only waned during the rise of Christianity and Islam. Unlike the God of the Hebrew Bible,5 many other gods of the Mediterranean world were sexual beings.

Judaism has always had to negotiate with neighboring religious expressions and this has included negotiating with various expressions of sexuality. This was no less true in the time of Jesus and Paul. But what was relatively new during this period of Western civilization was widespread religious “asceticism.”

ASCETICISM

As mentioned previously, asceticism is the belief that a new and better self can emerge when a person withdraws from normal life (variously defined). Ascetic expression also included the practice of physical deprivation. Ascetics in Greek culture often deprived themselves of food, comfort, family, and sex, believing that they could achieve a more advanced spirituality by doing so.

Many ascetics believed that the physical world was evil and that the human spirit was hindered by physical appetites. While this is a common religious expression in Jainism and Buddhism, Greek asceticism developed from athletic training and philosophy. Within this general life ethic, abstinence from sex was thought to open the possibility for a better spiritual existence. So the philosophical inclination to view sex as evil was already thriving in the sixth century B.C.E., but it took a few more centuries for it to become a widespread religious expression.6

Because Judaism was always negotiating with neighboring religions and cultures, Jewish life took on different forms in different times and places. In short, there were many ways to live a Jewish life during Jesus’ time. In addition to the many fertility rituals that were practiced throughout the Mediterranean, there were other groups that attempted to abstain from sex altogether.

Some Jews were quite interested in Greek philosophy and some were less interested. And in the midst of this plurality, most Jews attempted to observe the very first commandment given by God to humanity in the Hebrew Bible: “Be fruitful and multiply.” A traditionally Jewish view would have acknowledged the intrinsic goodness of the physical world. Sex would have been seen as a requirement from this perspective. Many Jewish teachers would have also seen sex as a source of pleasure as well. Consider the Jewish saying found in the book of Proverbs:

Let your fountain be blessed,

and rejoice in the wife of your youth,

a lovely deer; a graceful doe.

May her breasts satisfy you at all times;

may you be intoxicated always by her love.7

The Jewish sage who wrote this encourages sexual expression for the sake of conjugal pleasure. He cautions against adultery, but (much like the Song of Songs) promotes a wider view of sexuality, complete with foreplay. For the author of this proverb, at least, sexual pleasure was not simply a by-product of procreation. Moreover, and most importantly, sexual pleasure was not seen as a sin that hindered one’s religious life.

Yet we know that some Jews during the time of Jesus and Paul became advocates of a more ascetic life, forsaking physical pleasure – and marriage along with it. Perhaps, as I’ve already suggested, John the Baptist is an example of this. While it would be misleading to paint Jewish life in the extremes of hedonism or asceticism, what can be said with a fairly high degree of confidence is that Judaism adopted or adapted several forms of Greek (and Persian) dualism in the centuries leading up to the birth of Christianity. Specifically, the belief that humanity was dual in nature – existing as both body and soul – was highly influential.

Judaism in that time and place included many Roman and Greek-influenced ways of life. I emphasize this because the Greeks and Romans had a wide range of ideas about sexuality, and some of these influenced the development of Christianity. Many early Christians incorporated ascetic expressions into their religion. A Roman physician and philosopher named Galen observed this of Christians: “They include not only men but also women who refrain from cohabitating all through their lives; and they also number individuals who, in self-discipline and self-control in matters of food and drink, and in their keen pursuit of justice, have attained a pitch not inferior to that of the genuine philosophers.”8 While Galen offers us a second-century perspective, it is quite likely that some of the earliest non-Jewish followers of Jesus were motivated by asceticism. Letters to the Christians in Corinth and to Timothy (among others) suggest that many Christians thought that sexuality was physical as opposed to spiritual.

There were also rumors that some Christians participated in orgies wherein husbands and wives would swing from one partner to the next. These rumors were widespread enough to warrant multiple Christian writers to refute them. Indeed, if Paul’s writings on the topic of Christian liberty were to be taken to an extreme, one can easily imagine this sort of sexually ecstatic worship in some Christian communities.

But Paul, the person most responsible for bringing Christianity to the non-Jewish world, writes in response to what he sees as extreme forms of sexuality among his contemporaries. He argues that extremes are problematic. Paul is critical of Christians who showed too little restraint, and was equally critical of those who tried to force celibacy onto others. That said, although deeply committed to Judaism, Paul seems to have been influenced by Greek culture in a number of ways. For example, he seems to have chosen a temporary life of celibacy during his missionary career. Paul does not think that marriage is evil, and seems open to the idea of getting married himself at some point.9 But it is important to recognize that the idea of celibacy would have seemed antithetical to Jewish life prior to Greek influence. It seems that many Jewish religious leaders during Jesus’ time struggled between Greek ideals and the constraints and liberties of traditional Jewish instruction (what we might loosely call “Torah”). My point here is a simple one: the more that Christianity became non-Jewish (more often than not, anti-Jewish), the less it was oriented toward traditional Jewish instruction about sexuality.

EXAMPLES OF CHRISTIAN ASCETICISM

The topic of Christian asceticism will be revisited often throughout this book. I will offer only a few examples here to illustrate the general development of the tradition. Consider an early Christian story found in a book called The Shepherd of Hermas. This text was very influential in many Christian circles in the second and third centuries. In fact, it was included alongside the Gospels and the letters of Paul in some cases. In Hermas, a religious pilgrim finds himself in the care of twelve virgins while he waits for his spiritual guide called “the shepherd.” Here is an excerpt from chapter eleven:

The virgins said to me, “The Shepherd does not come here today.” “What, then,” said I, “am I to do?” They replied, “Wait for him until he comes; and if he comes he will converse with you, and if he does not come you will remain here with us until he does come.” I said to them, “I will wait for him until it is late; and if he does not arrive, I will go away into the house, and come back early in the morning.” And they answered and said to me, “You were entrusted to us; you cannot go away from us.” “Where, then,” I said, “am I to remain?” “You will sleep with us,” they replied, “as a brother, and not as a husband: for you are our brother, and for the time to come we intend to abide with you, for we love you exceedingly!”

But I was ashamed to remain with them. And she who seemed to be the first among them began to kiss me. And the others seeing her kissing me, began also to kiss me, and to lead me round the tower, and to play with me. And I, too, became like a young man, and began to play with them: for some of them formed a chorus, and others danced, and others sang; and I, keeping silence, walked with them around the tower, and was merry with them. And when it grew late I wished to go into the house; and they would not let me, but detained me. So I remained with them during the night, and slept beside the tower.

Now the virgins spread their linen tunics on the ground, and made me lie down in the midst of them; and they did nothing at all but pray; and I without ceasing prayed with them, and not less than they. And the virgins rejoiced because I thus prayed. And I remained there with the virgins until the next day at the second hour.

The spiritual shepherd returns to find that the pilgrim has remained chaste. He has kissed, danced, and slept alongside a dozen naked virgins. But he has climaxed in prayer rather than coitus. This story has several parallels with Greek erotic literature but takes on an especially ascetic tone. If you’re familiar with the film The Big Lebowski, you’ll find a few parallels there too.10

The Shepherd of Hermas was eventually excluded from the New Testament, but the ideals expressed in this story became integral for non-Jewish Christianity. To abstain from sex was holy. Celibacy in the face of temptation was heroic. Sin and sex became almost synonymous after Christianity and Judaism parted ways.

Saint Jerome is often pointed to as the crusader against sex and women in general. He argued that marriage was the result of sin and that sex was a necessary evil. His views on marriage are more nuanced than is normally recognized, but his basic belief was that “virginity is natural while wedlock only follows guilt.”11 But pointing to a few especially misogynistic quotes from Jerome can obscure how prevalent this logic was in mainstream Christianity.

Augustine of Hippo, perhaps the most influential theologian in the history of Christianity, rejected the idea that the human body, and the physical world in general, was evil: “For the soul and the body, and all the natural endowments which are implanted in the soul and the body, even in the persons of sinful men, are still gifts of God.”12 Augustine, unlike many ascetic Christians, supported the idea of marriage. But Augustine never fully embraced the virtue of sexual pleasure in the way that the author of Proverbs 5 suggests. Augustine encouraged married couples to abstain from sex unless it was for the purpose of procreation. He wrote: ‘The union, then, of male and female for the purpose of procreation is the natural good of marriage. But he makes a bad use of this good who uses it bestially, so that his intention is on the gratification of lust, instead of the desire of offspring.’13

Notice here Augustine’s either/or mentality. Either sex is motivated by the desire for children or it is beastly. Augustine is generally remembered as the Christian champion against asceticism. But here we see a carryover. He is clearly suspicious of sexual pleasure when pursued for its own sake. This view, represented with prominence by Augustine, became the standard for Christianity.

Almost a millennium later, theologian Thomas Aquinas reflected on Augustine’s view of sexuality. Aquinas wrote: “The exceeding pleasure attaching to a venereal act, directed according to reason, is not opposed to the mean of virtue.”14 Here, Aquinas defends sexual pleasure. It is not, he argues, to be reduced to lust when it is experienced “according to reason.” For Aquinas, such pleasure was reasonable when it was done for the purpose of procreation. Again, we see that even the least ascetic Christian theologians were unable to commend sexual pleasure without reservation.

The history of Christianity has included a long and robust debate about sexuality. There have been prominent voices on either side of this debate. But the reason that the debate was necessary in the first place is because the Church adopted and adapted Greek asceticism. The belief that the physical world was only a shade of a higher reality − and that therefore physical pleasure is to be shunned − is not a teaching that came from Jesus.

PHANTOM JESUS

After centuries of debate, the voices that affirmed the essential goodness of the creation and creatures won. Christians such as Marcion (c. 85–c. 160), who argued that the God of the “Old Testament” was a demiurge (a lesser god) who created an evil world, lost the debate. Christians like Augustine, who affirmed the claim of Genesis that all creation was created with inherent goodness, won the debate. In this case, the “winners” wrote the doctrines that would provide a foundation for Christianity.

But before the losers were obscured by historians, these “heretics” were quite successful at reinventing a non-physical Jesus. Their logic can be summed up like this: because the physical world is evil, Jesus could not have been physical. Their Jesus never left footprints when he walked. He was an entirely spiritual being who wore a mask of physicality. Some even argued that Jesus never had a bowel movement because he had super-special innards! A Christian named Valentinus (c. 100–c. 160) is purported to have said: ‘Jesus digested divinity; he ate and drank in a special way, without excreting his solids. He had such a great capacity for continence that the nourishment within him was not corrupted, for he did not experience corruption.’15

While it is difficult to reconstruct the thinking of Valentinus with any confidence, this saying at least illustrates a popular portrait of Jesus in the second century. For many Christians, Jesus could only be pure if he was without physicality.

Around one hundred years after Jesus’ crucifixion, Christians began debates about his celibacy. Tatian was a second-century theologian who (following the lead of Justin Martyr) argued that Jesus never married. While Tatian was labeled a heretic for many of his views, his idea about Jesus’ celibacy became entrenched in popular Christianity. It is worth noting that Tatian also taught that Satan invented sex and that Adam (not God) instituted the union of Adam and Eve. In the latter half of the second century, Clement of Alexandria offered a response to this view:

There are those who say openly that marriage is fornication. They lay it down as a dogma that it was instituted by the devil. They are arrogant and claim to be emulating the Lord [Christ] who did not marry and had no earthly possessions. They do not know the reason why the Lord did not marry. In the first place, he had his own bride, the Church. Secondly, he was not a common man to need a physical partner. Further, he did not have an obligation to produce children; he was born God’s only son and survives eternally.16

Here, Clement reacts to the view that marriage is a concession to our carnal natures. He has his own reasons to believe that Jesus was celibate. Clement’s rationale will be revisited elsewhere in this book. For now, notice that both Clement and these supposed heretics assume that Jesus did not marry. Clement’s assumption of Jesus’ celibacy suggests that – by the second century – many Christians assumed that Jesus never married; it was the question “why not?” that fueled debate. If so, do these second-century debates tell us something of Jesus’ first-century reputation?17

While Christian doctrine eventually celebrated the full humanity of Jesus, the invention of Jesus’ celibacy on ascetic grounds would have a long legacy within Christianity. This belief seems to stem from the anti-physical and anti-sexual ideologies made popular in the second century. These early ascetic Christians could not imagine a wife of Jesus because they were convinced that Jesus shunned physical pleasure and comfort. In some cases, this ascetic Jesus wasn’t even flesh and blood, but entirely spirit. But the portraits of Jesus from our earliest documents suggest that his physicality was affirmed even by those who were earnestly convinced that Jesus was divine.

Paul repeats the early Christian belief that Jesus was “born according to the flesh.” Our earliest documents suggest that Jesus was not an ascetic, but was known for drinking and feasting. The ascetic foundations for the belief in Jesus’ celibacy do not square with the earliest portraits of Jesus.

CHALLENGES

The apostolic church and professional historians have always claimed interest in Jesus’ “full humanity.” But any theology or history that portrays a Jesus devoid of sexual identity falls short of the task. Jesus may well have chosen a life of celibacy, but to build this claim upon the assumption that sex is sinful is faulty. Moreover, the hope that a celibate life might diminish or “solve” one’s sexual nature is a pious deception.

The certainty of Jesus’ celibacy by second-century Christians was misguided. Whatever conclusion is forwarded concerning Jesus’ marital status, we must acknowledge that the traditional assumptions for Jesus’ celibacy are unsustainable. It may be impossible to pursue the topic of this book objectively, but I believe that it is possible to do so honestly. Honesty compels me to observe that (1) second-century Christian assumptions about sexuality were generally damaging to their portraits of Jesus and (2) the impact that these assumptions had on the Christianized West were wildly successful, to ill effect.

That said, we should be aware of our own agendas. Are we to lean toward Jesus’ celibacy because tradition is on our side? Do we quest for a wife of Jesus because we’re repulsed by Christian asceticism? Are we preconditioned to “discover” Jesus’ wife because we need an archetype that can provide symbolic value for our shifting views of sexuality? Is it possible that we aim to invent a married Jesus because our favorite heroes are sexual conquistadors?

It might not be possible to remove these kinds of biases. All historical quests are inevitably laden with ideological baggage. But we should, at least, be aware of the questions we bring with us on this quest.

FURTHER READING

Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988).

Elizabeth Clark (ed.), St. Augustine on Marriage and Sexuality: Selections from the Fathers of the Church (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1996).

James D. G. Dunn, Christian Liberty: A New Testament Perspective: The Didsbury Lectures (Carlisle: Paternoster Press, 1993).

Alexander R. Pruss, One Body: An Essay in Christian Sexual Ethics; ND Studies in Ethics and Culture (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2012).

Vincent L. Wimbush and Richard Valantasis (eds), Asceticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).