“No other biblical figure – including Judas and perhaps even Jesus – has had such a vivid and bizarre post-biblical life in the human imagination, in legend, and in art.”

– JANE SCHABERG

The topic of Jesus’ sexuality has traditionally been taboo. But those who have ventured to explore it have demonstrated a variously “normal” Jesus. Whether Jesus is struggling with his desires, as in Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Last Temptation of Christ1 (on which the Scorsese film is based), or he is married with children as with Dan Brown’s portrait, or he is sacrificially celibate as with John P. Meier’s portrait,2 the Jesus that scandalizes us is (most often) a man who embodies the sexual norms of the Christianized West. Dale B. Martin writes: “I have no interest in arguing for any of these different proposals for Jesus’ sexuality. I find certain assumptions undergirding each of them difficult to accept. What is more interesting for my purposes is how they illustrate what has been imaginable at different times with regard to the sexuality of Jesus – and what has been apparently unimaginable.”3 Martin’s point offers us a way forward. We can learn much about a culture from that culture’s collective imagination. We can also learn a great deal about a culture from its imaginative limits.

In this chapter, I will sketch the story of how Mary Magdalene became imaginable as the wife of Jesus. I will survey her emergence as “the sinful woman” and show how, in the imaginations of medieval Christianity, she eventually became a prostitute. I will then speak to Mary’s very recent transformation from wanton to wife.

MAGDALENE IN POPULAR IMAGINATION

In 591, Pope Gregory I declares (and thus lends official authority to) what was probably a common belief: that Mary Magdalene, Mary the sister of Martha and Lazarus, and the nameless “sinner” who washed and kissed the feet of Jesus in Luke 7, were the same person. Gregory believes that she is “the woman John calls Mary, and that Mary from whom Mark says seven demons were cast out. And what did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices?”

Although the New Testament does not specify that these three women are the same person, Gregory creatively conflates them.4 In doing so, he transforms Mary into a sinner and infuses her legacy with scandal:

It is clear, brothers, that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts. What she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was not offering to God in a more praiseworthy manner. She had coveted with earthly eyes, but now through penitence these are consumed with tears. She displayed her hair to set off her face, but now her hair dries her tears. She had spoken proud things with her mouth, but in kissing the Lord’s feet, she now planted her mouth on the Redeemer’s feet. For every delight, therefore, she had had in herself, she now immolated herself. She turned the mass of crimes to virtues, in order to serve God entirely in penance, for as much as she had wrongly held God in contempt.5

Gregory paints a portrait of a woman who once perfumed “her flesh in forbidden acts” but became repentant at the feet of Jesus. This image of a sinful woman turned virtuously submissive dominated Catholic commemoration of Magdalene for the next fourteen centuries.6

In 1260 an archbishop named Jacobus de Voragine wrote a historical fiction of Magdalene’s life where he repeats Gregory’s merger of Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene. Jacobus also imagines how she might have fallen into prostitution:

She was wellborn, descended of royal stock. Her father’s name was Syrus, her mother was called Eucharia. With her brother Lazarus and her sister Martha, she owned Magdalum, a walled town two miles from Genezareth, along Bethany, not far from Jerusalem, and a considerable part of Jerusalem itself … Magdalene, then, was very rich, and sensuous pleasure keeps company with great wealth. Renown as she was for her beauty and her riches, she was no less known for the way she gave her body to pleasure – so much so that her proper name was forgotten and she was commonly called “the sinner.”7

Jacobus exploits the name of Mary’s village (thought to be “Magdala”) and portrays her as a wealthy, indeed royal, woman of a great city. He then describes how her wealth gave way to sensuous pleasures. Jacobus renders her explicitly – if implausibly – as a prostitute. He also mimics the standard image of Mary as a repentant sinner.

The portrait of Mary’s repentance became important during the Protestant Reformation. In 1566, Bishop Hugh Latimer said this in a sermon: “I doubt not we all be Magdalenes in falling into sin and in offending: but we be not again Magdalenes in knowing ourselves and rising from sin.”8 Here Mary becomes a model for the Christian life. Latimer’s Magdalene represents all of humanity, steeped in sin, but redeemed by grace. In Latimer’s sermon we see no attempt to merge the lives of the tearful woman of Luke 7, and the woman who witnessed the resurrection in Mark, chapter sixteen. That Mary was the sinner par excellence is simply assumed.

But the Reformation made readers out of many, and countless non-clergy began to read the Bible. An interesting example of this comes from the pen of the poet John Donne (1572–1631). Donne demonstrates that not everyone swallowed Gregory’s portrait of Mary:

Her of your name, whose fair inheritance

Bethina was, and jointure Magdalo:

An active faith so highly did advance,

That she once knew, more than the Church did know,

The Resurrection; so much good there is

Deliver’d of her, that some Fathers be

Loth to believe one Woman could do this;

But, think these Magdalens were two or three.9

Here Donne demonstrates that some “Fathers” believed that there were multiple women represented in the stories that Gregory conflated. Notice, however, that Donne maintains the Bethany connection and imagines that Mary was wealthy. English literature scholar Alison Chapman is probably correct to think that Donne has borrowed from Jacobus’s portrayal of Mary as a wealthy woman but omits her descent into prostitution.10

Jacobus’s portrait eventually found its way to the silver screen. In Cecil B. DeMille’s 1927 King of Kings, “Mary of Magdala” is a wealthy socialite. The second frame of the movie reads: “In Judea – groaning under the iron heel of Rome – the beautiful courtesan, MARY of MAGDALA, laughed alike at God and Man.”11 Mary petulantly orders her servants to fetch her perfume. She travels by way of chariot driven by zebras (a gift from the Nubian King). At one point she grabs a male guest by the throat and pins him down, demanding information from him. Even so, her portrait is sexualized as she entertains several wealthy men who flirt with her and beg her for kisses. When she eventually meets Jesus, he casts out her demons, the first of which is Lust. After the exorcism is complete, Mary covers herself to convey her new spirit of diminutive modesty and kneels to wash the feet of a radiant Jesus.

Thus the image of Mary as a wealthy, but sex-driven woman continued into the modern era. The description of Mary as a “courtesan” hints at the modern usage of the word as “prostitute” but casts her in a Renaissance-style role as a “woman at court.” So Mary Magdalene’s image as a reformed prostitute, while cleverly disguised in DeMille’s film, is given homage. Indeed, Mary’s portrait as a reformed prostitute continues to dominate her commemoration in the Christianized West.

In 1945, the unearthing of the Nag Hammadi Library would change Mary’s popular image dramatically. The Gospel of Philip (as discussed in the previous chapter) suggested the possibility that Jesus and Mary were lovers, or at least that some third-century mystics played with this metaphor. Shortly after these gospels were found, the novelist, philosopher, and politician Nikos Kazantzakis published his novel The Last Temptation of Christ.

In this historical fiction, Mary’s life as a prostitute is central to the plot. Jesus is attracted to her and struggles with his desires for sexual gratification and for marital normalcy. In this “dream,” Jesus imagines himself married to Magdalene, who soon becomes pregnant. Soon after, Mary dies and Jesus’ dream of a family is shattered. Jesus then settles down with Mary and Martha to start a family. Thus Kazantzakis does not make the mistake of merging Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany. Martin Scorsese’s film adaption of the book repeats this portrait.12

In one scene, toward the beginning of the film, Jesus sheepishly enters Mary’s brothel and watches her having sex with multiple clients. The screenplay reads:

Besides the young Indian nobleman (with three gold bands around his ankles), there are three Bedouin, three old men with painted eyelashes and nails, two young men with black beards and moustaches, and two rich black merchants. An old lady is off to one side crouched on the ground with a small cage containing some crabs. A small fire is beside her on which she is cooking food. There is no door to Magdalene’s room where she does business, only a wispy half torn curtain floating in the infrequent breeze. This affords her waiting clients a half-darkened view of the proceedings. An Arab makes love to her. She is nude, and good at her work.13

Played by actor Willem Dafoe, this Jesus waits and watches and then struggles to ask for Mary’s forgiveness. Mary is hostile to Jesus’ false piety and accuses him of hypocrisy. Jesus tells her, “God can save your soul.” Mary replies, “I don’t want him. He’s already broken my heart.” In this portrait, Mary sounds like a modern woman who has lost her faith. In contrast, Jesus is a tortured soul, struggling with his sexual desires and trying to purge them.

Both characters develop toward redemption as Jesus begins his mission. Jesus’ sin thereafter – his last temptation – is experienced in his imagination as he struggles with his vocation as the messiah. Mary’s repentance is imagined differently than Jacobus de Voragine’s medieval portrait, but she still moves from prostitute to follower of Jesus.

The scandal that surrounded The Last Temptation of Christ keyed on Jesus’ imaginary hope for a life of normalcy. Christians, in particular, boycotted the film and attempted to ban the book because the thought of Jesus’ sexual imagination was sacrilegious.14 Very little of the media coverage was devoted to questioning Mary’s sexualized portrait. Few, it seems, had a problem with Mary’s portrait as a prostitute. This assumption was so ingrained in the popular imagination of the Christianized West that Mary’s prostitution was uncontroversial.

In the mid-1990s the Dave Matthews Band was one of the most internationally recognized rock groups. At the height of their popularity, the band put out an acoustic song titled “Christmas Song.”15 The song’s message and common refrain framed the life of Jesus in “love, love, love.” Love is “all around” is repeated in successive stages of Jesus’ life. The song begins by labelling Mary and Joseph boyfriend and girlfriend. The wise men come to shower the new baby with love. When Jesus grows up he meets another Mary who is of ill repute. Moreover, this Mary is willing to sell her reputation for a reasonable fee. And yet, Jesus’ heart is full of love for Mary. This song reinforces Mary’s popular depiction as a prostitute. The song suggests – not so subtly – that this less-than-reputable Mary was Jesus’ lover. Here we see that the image of Mary Magdalene the repentant sinner has been eclipsed by Mary the prostitute turned lover. But the song also shows how successful Kazantzakis was. Less subtle is a fictional exchange between Stephen King’s “gunslinger” and a priest. The gunslinger asks if Jesus was ever married. The priest retorts, “No… but His girlfriend was a whore.” While Magdalene is not named, King’s fictional priest confirms a popular reading of her legacy.16

Other seeds of change in Mary’s public persona are seen in a poem by Veronica Patterson. Patterson’s poem is titled “I Want to Say Your Name: a love poem.”17 The subtitle is crucial to understanding what follows. The poem begins in the first person; the poet’s voice calling to a lover. The poet wants to say the lover’s name “the way Jesus said ‘Mary.’” In this way, the poet is drawing a parallel between Mary and Jesus and two modern lovers. Mary stands with Jesus at the open tomb after Jesus has resurrected from the grave. She wants to touch him but he tells her that she cannot. Jesus is in between death and life, the physical and spiritual, and he cannot accept physical affection. Still the poet creates a palpable tension between Jesus and Mary. The poem climaxes with a simple and profound intimacy:

“Mary,” he said, and she changed, as if

an hour earlier she had been a child, Her name

held all of her and it was his gift.

In Patterson’s poem – called “a love poem” – Mary is intimately known. There is no mistaking her identity; “Her name held all of her” and Jesus knew her. Moreover, the imagined setting returns us to the empty tomb of Jesus: the place where Mary Magdalene is most associated in the four biblical Gospels. This is not the prostitute, the sinner, or the sister of Martha. The intimacy between Mary and Jesus has eclipsed all else. But, like Donne’s poem, Patterson’s imagination is exceptional. It doesn’t represent the more popular image of Mary the prostitute.

Remarkably, it wasn’t until Dan Brown’s massively popular novel that the general public began to imagine a Mary devoid of prostitution. The idea that she was Jesus’ lover was fascinating, but the proposal that she was the wife of Jesus was a runaway hit. In Brown’s detective mystery, a modern French woman named Sophie learns of an ancient cover-up concerning the marriage of Jesus and Mary. According to the story, this secret “history” has been communicated through the work of Renaissance artist Leonardo Da Vinci. Brown writes:

Sophie moved closer to the image [of Da Vinci’s Last Supper]. The woman to Jesus’ right was young and pious-looking, with a demure face, beautiful red hair, and hands folded quietly. This is the woman who singlehandedly could crumble the Church?

“Who is she?” Sophie asked.

“That, my dear,” Teabing replied, “is Mary Magdalene.”

Sophie turned. “The prostitute?”

Teabing drew a short breath, as if the word had injured him personally. “Magdalene was no such thing. That unfortunate misconception is the legacy of a smear campaign launched by the early Church.”18

This portrait of Magdalene as the secret wife of Jesus was too compelling to ignore, and just scandalous enough to turn a fun detective novel into an international debate. The novel dominated the New York Times bestsellers list for over two years (2003–05) and was boycotted by many churches when it was made into a film. Multiple books by Christian scholars and apologists were published for the sole purpose of exposing the historical inaccuracies of the book.

But for all of the book’s fictive elements (it was fiction, after all), Dan Brown probably did the most to expose Gregory’s fallacy to the general public. The fictitious Mary of The Da Vinci Code was not a prostitute. Brown’s Mary was, however, royalty. A key element to the plotline was that both Mary and Jesus were of royal lineage.19 This, of course, recalls the historical fiction by Jacobus in the thirteenth century. Brown discarded what he did not like of the medieval historical fiction and kept what would most help his plot. Ironically, his fiction undermined the fictitious image of Mary as a prostitute.

There are now two competing images of Mary in the popular imagination of the Christianized West. The first is Mary the prostitute; the second is Mary the wife of Jesus. The former can be traced to the Middle Ages, and the latter has emerged as a contender only in recent years.

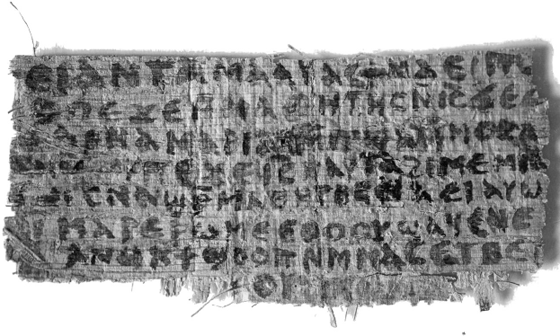

THE GOSPEL OF JESUS’ WIFE

In September 2012, the International Congress of Coptic Studies was hosted in Rome. At this conference, a well-respected Harvard scholar, Karen King, announced that an anonymous collector had produced an ancient fragment that looked to be a fourth-century fragment of a second-century gospel. King titled this fragment the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife. This small piece of papyrus contains a few Coptic phrases that caused an immediate media frenzy. Translated, the entire fragment reads:20

Side One:

1 ] “not [to] me. My mother gave to me li[fe …”

2 ] The disciples said to Jesus, “.[

3 ] deny. Mary is worthy of it [

4 ] …” Jesus said to them, “My wife.[

5 ] … she will be able to be my disciple … [

6 ] Let wicked people swell up … [

7 ] As for me, I dwell with her in order to. [

8 ] an image [

Side Two:

1 ] my moth[er

2 ] three [

3 ] … [

4 ] forth which … [

5 ] (illegible ink traces)

6 ] (illegible ink traces)

As you can see, this gospel is little more than a few disjointed phrases. Among these phrases, quite clearly, is the phrase “my wife.” Coupled with the phrase “I dwell with her,” this document offers evidence that the author linked Jesus and Mary together as husband and wife. If this fragment is ancient, it would be the first reference to a literal wife of Jesus. Recalling my previous discussion of the Gospel of Philip, some had imagined Mary as the “lover” of Jesus, but not specifically as his wife.

The paper by King was published on the Harvard webpage and provisionally accepted by the Harvard Theological Review. At least two experts (papyrologists) who were consulted before the announcement were relatively convinced that the document was authentic. But King was also alerted to the fact that one of the reviewers pointed to several problems with the fragment, suggesting that it was a modern forgery. Within a week of this announcement, several other scholars went on the record arguing that it was a fraud. In the months that followed, the scholarly consensus leaned more and more toward forgery.

New Testament scholar Francis Watson writes: “The text has been constructed out of small pieces – words or phrases – culled from the Coptic Gospel of Thomas … and set in new contexts. This is most probably the compositional procedure of a modern author who is not a native speaker of Coptic.”21 Many others, agreeing with Watson, pointed out that the phrases culled from the Gospel of Thomas provided just the right amount of information to scandalize the general public.

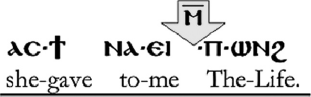

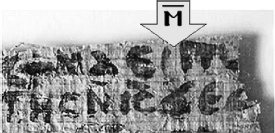

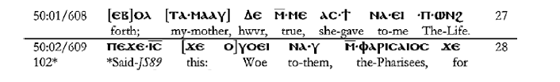

Among the many arguments for forgery is an intriguing suggestion from Oxford-educated researcher Andrew Bernhard.22 Bernhard observes that every phrase23 in the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife could have been stolen from an online Coptic-English resource called an “interlinear.”24 Interlinears are used by students as translation aids. As seen in the example below, the English translation is typically set in between the lines of the ancient text.

What I provide here shows that the exact phrase found in the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife is present in the Coptic Gospel of Thomas. Both texts contain the phrase “my mother gave me life.”

It just so happens that this particular online text contains a typo. It leaves out a prefix, a definite object marker that looks like  . I have enlarged the problematic portion here:

. I have enlarged the problematic portion here:

This oddity is not found in any ancient manuscript related to Christianity. It is unique to this modern reproduction that has been available online since 1997. In fact, this typo has been corrected in other online versions of the Gospel of Thomas. But the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife contains the same oddity:

I have shown here where the prefix should have been. Again, this oddity can only be found in the online interlinear shown above. Let me put this as bluntly as I can: if Bernhard is correct, the author of this document had an internet connection. If so, it is a very modern forgery.

What is more interesting to me is the timing of this discovery and the media coverage that exploded when it was announced. Whether authentic or not, the news media’s coverage of this text reveals a great deal about Mary’s newly minted image. Despite King’s clear and repeated efforts to the contrary, the international news media sold this story as if it might reveal something about the historical Jesus. In the first paragraph of King’s paper, she writes: “This is the only extant ancient text which explicitly portrays Jesus as referring to a wife. It does not, however, provide evidence that the historical Jesus was married, given the late date of the fragment and the probable date of original composition only in the second half of the second century.”

This is an important statement because the story that circulated on the blogosphere, on the evening news, and on several comedy programs assumed that this gospel was published to say something scandalous about Jesus himself. Clearly, King had hoped to contribute to the discussion about second-century Christianity, not historical Jesus research. A journalist for the New York Times, Laurie Goodstein, wrote one of the first articles about King’s fragment: “[King] repeatedly cautioned that this fragment should not be taken as proof that Jesus, the historical person, was actually married. The text was probably written centuries after Jesus lived, and all other early, historically reliable Christian literature is silent on the question.”

But in the same article, Goodstein also wrote: “Even with many questions unsettled, the discovery could reignite the debate over whether Jesus was married, whether Mary Magdalene was his wife and whether he had a female disciple. These debates date to the early centuries of Christianity, scholars say. But they are relevant today, when global Christianity is roiling over the place of women in ministry and the boundaries of marriage.”25

Seemingly, this paragraph is an invitation to us, the readers, to reconsider our own “roiling” debates. Like many other innovations to the popular image of Mary, our own concerns drive our collective imaginings of Mary. It matters very little whether or not Mary was Jesus’ wife. What makes this fragment relevant, according to Goodstein, is the opportunity it creates for us to continue the cultural debates that are already under way.

Notice the way that Reuters’ journalist Philip Pullella frames this discovery: “The idea that Jesus was married resurfaces regularly in popular culture, notably with the 2003 publication of Dan Brown’s best-seller ‘The Da Vinci Code,’ which angered the Vatican because it was based on the idea that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene and had children.”26

In order to tap into (and fuel) the popular imaginations of the general public, Pullella invites his readers to remember the controversies stirred by Dan Brown’s fiction. Undoubtedly, it is the Mary Magdalene of fiction that guides our collective imagination and allows us to focus our agendas. Even when discussing ancient possibilities, it is near impossible to keep our popular portraits of Mary and Jesus in the realm of the imagination.

With this in mind, I will point out the obvious: as compared to the two-thousand-year history of popular portraits of Mary Magdalene, the notion that she was literally married to Jesus is ten years young. The seeds were planted in our imagination by the discovery of the Gospel of Philip. Mary was sensationalized by Kazantzakis’s Jesus, who imagined himself as a married man. But the image of Mary as the literal wife of Jesus was novel in 2003. Could it be that the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife fragment emerged specifically to fan the controversies specific to the third millennium?

We should expect our popular images of Mary Magdalene to embody our social debates and agendas. Judging from the way that the various news outlets reported the story of this fragment, we are actively looking for ways to fuel our debates and support our agendas. We should also expect that these debates and agendas will bleed into our historical portraits as well.

CHALLENGES

In the first two centuries after Mary Magdalene’s death she went from disciple, to obscurity, to a target for misogyny. Her legacy was confused with Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus. Parallel to this progression, Mary became the ideal and transcendent disciple, and an object of jealousy. From the Middle Ages onward, she became the harbinger of vices. Twelve hundred years after she died, she became inexplicably wealthy. She was royalty, owner of a walled city, but tragically given to sensuality. In short, Mary Magdalene became a prostitute in the imaginations of the Christianized West. She became the exemplary sinner and the model of penitence during the Reformation. In the modern world – sexualized as she was – she became a modern, worldly woman. She was the object of Jesus’ desire and temptation. She became the lover of Jesus and then, finally, the wife of Jesus.

At each turn, Mary Magdalene reflected the debates and agendas of those who imagined her. Our latest notion that she was the wife of Jesus must reflect something about us as a culture. Her recent marriage to Jesus is an opportunity for us to become more aware of ourselves. Otherwise we unwittingly project ourselves onto our discoveries.

Esther A. de Boer and John Bowden, The Mary Magdalene Cover-Up: The Sources Behind the Myth (London: T & T Clark, 2006).

Bart D. Ehrman, Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Darren J. N. Middleton, Scandalizing Jesus?: Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ Fifty Years On (London: Bloomsbury, 2005).

Jane Schaberg with Melanie Johnson-Debaufre, Mary Magdalene Understood (New York: Continuum, 2006).

. I have enlarged the problematic portion here:

. I have enlarged the problematic portion here: