32

On Reading Minds

The question of the transference of thoughts has long preoccupied me, not just through the twins with their simultaneous speech; and it’s not by chance that I’m currently engaged on a documentary film on the “reading” of brain activity. It’s possible by now, with the help of electromagnetic waves emitted by the brain, to transfer the human will to a robot. I have seen a paraplegic woman, merely by willpower, steer a mechanical arm to pick up a glass of water and a straw, and lift them to her mouth. By using magnetic resonance imaging, we can follow brain activity so minutely that we can tell if someone is reading a text in English or Spanish. It’s possible to take a person’s mere imagining of two elephants crossing the savanna from left to right, and turn it, by a computer scanning the brain waves, into an admittedly somewhat blurred image. By graphically transcribing complex brain activity, it’s possible to be fairly sure if someone is lying or not much more accurately than by using a lie detector, which only responds to physical signals: pulse, blood pressure, and breathing frequency. It’s perfectly right that such polygraphs are not admitted in evidence in court, but such is the rapid pace of change in the scrutiny of brain activity that the autonomy and inviolability of our thoughts will soon need some legal definition and protection. There is already a draft agreement of the rights of the individual to the inviolability of thought, just as there is an international agreement banning certain chemical and biological weapons. Chile is the first nation to have adopted this in an appendix to its constitution. This no doubt goes back to the abuse of human rights that took place under the dictatorship of General Pinochet. I have been given leave to record the deliberations of committees of senators and parliamentarians on the subject via Zoom.

I have visited a temporary holding pen for nuclear materials in New Mexico, where radioactive barrels are stored in vast salt mines. The project is overwhelmingly disapproved of by the locals even though the mines are deep underground and have experienced no geological change for 250 million years. The question is: How do we warn future generations not to enter the mine? In the space of a few thousand years, no one will speak or understand our languages in their present form. It’s even possible that all our languages will be gone. Of the 6,500 languages currently in existence, we lose one every ten to fourteen days—and almost always the loss is not even recorded. This is a deeply alarming rate of extinction, much faster than the loss of mammals, whales, snow leopards, or other vertebrates like frogs. So how can we generate a warning sign about the radioactive poison that will be generally comprehensible to human societies in the future? There was a competition in which all the cartoonlike pictorial ideas proceeded from the certain assumption that future peoples with future cultural backgrounds will be able to “read” such pictures. As long ago as my 1969 film, The Flying Doctors of East Africa, in a sequence on a campaign of preventive medicine in Uganda, I showed how the inhabitants of a remote village were perplexed by the posters that were used. They had neither newspapers nor books nor television. Grown curious, I asked what they saw on the public health poster of an oversize eye, and the answers varied from a rising sun to a big fish even though the previous image had been used to demonstrate how to protect the eye from infection. I finally hung up four of the images used in the teaching campaign side by side, with one deliberately hung upside down. I asked individuals to identify which picture was upside down, and barely a third could do so correctly. For them, the posters must have been a bewildering mishmash of colors, much as abstract paintings are to us. It was clear to me that it wasn’t the villagers who were stupid so much as the medical helpers from the outside who could not imagine that pictures from our civilization were illegible to the villagers. Why were young Maasai warriors, athletic young men, incapable of climbing four steps up to a mobile clinic that contained a small lab and an X-ray machine? They shuffle around full of shame, as though walking on eggs. It was to do with taboos and barriers that the doctors didn’t understand any more than I did.

How the pictures of the distant future are to be formed has always preoccupied me. Even if we must imagine a future without a script, without any understanding of historical connections, I can envisage a scale of forty thousand years, which is as far as the distance from the Chauvet Cave to the present. Books will have disappeared; the internet and constellations will have changed; the Big Dipper will be much more elongated. For the nuclear dump in New Mexico, someone had the idea of turning the cacti cobalt blue through genetic mutation as a kind of warning of nuclear threat, but it’s just as likely that they would have spread right across North and South America or perhaps gone extinct altogether from climate change.

Reading signs, reading the other team’s tactics in soccer, reading the world, all that never let go of me. It is a theme in Kaspar Hauser, where the young protagonist is projected into the world, as if from a distant planet, without any understanding of houses, trees, the clouds in the sky; without language, without understanding the people around him. In the case of the deaf and blind characters in Land of Silence and Darkness, I was moved by the way they perceived the world, and the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks got in touch with me for that reason. He found the film so fascinating that he bought a 16 mm copy and repeatedly showed it to his students. Early on, I read his book Awakenings, where he describes patients who, as a consequence of a type of encephalitis, spent forty years in unconsciousness and were suddenly woken by a new drug into a world where another world war had taken place and airplanes transported vast numbers of people, a world where there was television and the Bomb. I had questions I wanted to ask him regarding sleep and hypnosis. He was familiar with my film Heart of Glass and the hypnosis scenes in it. I had no one else I could talk to about the deciphering of Linear B.

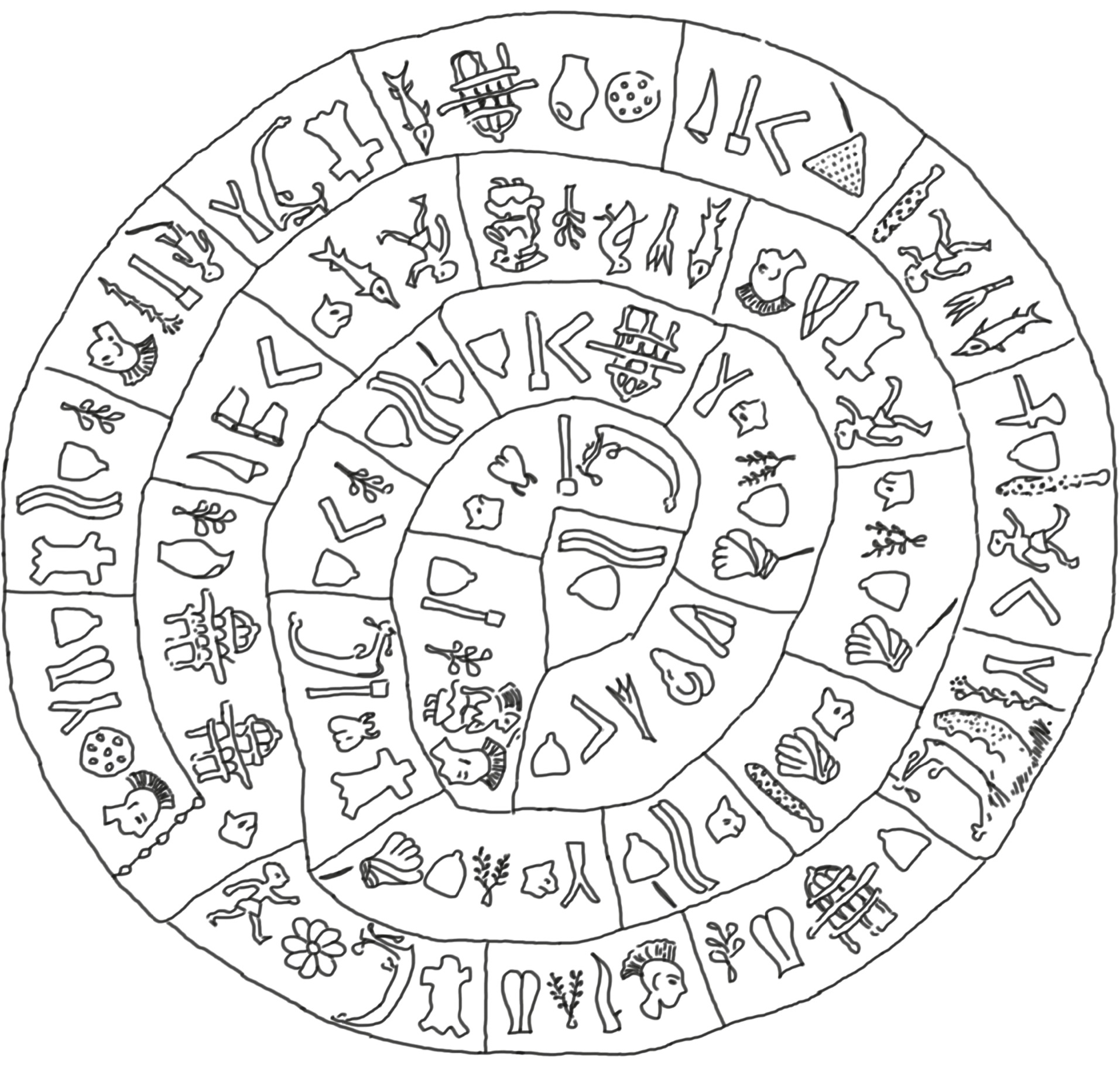

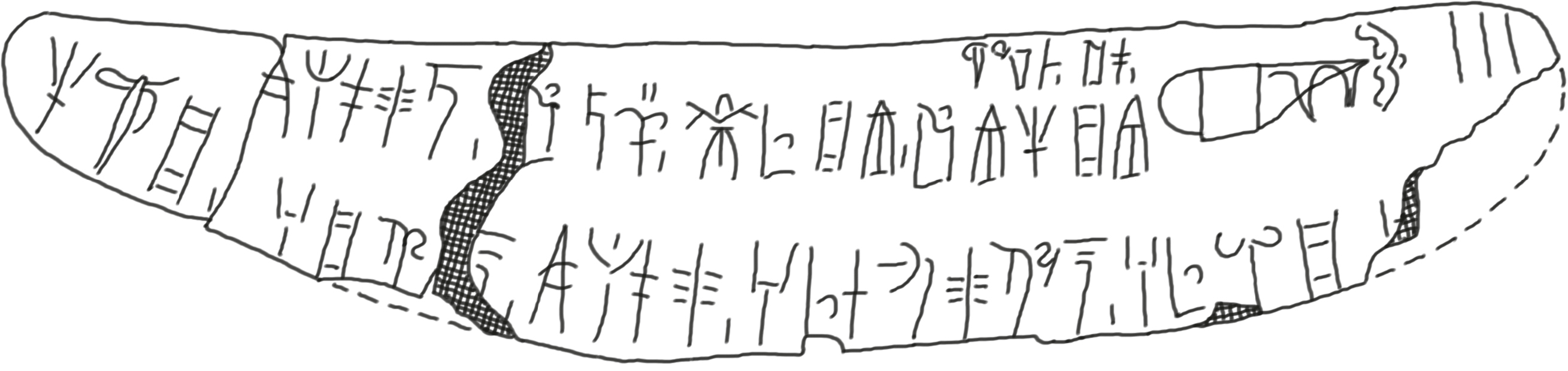

Linear B is a Bronze Age script that was used on baked clay tablets on the island of Crete and on the Greek mainland in Pylos and Mycenae. Here is an example of it from the 1956 book Documents in Mycenaean Greek by Michael Ventris and John Chadwick.

To me, the deciphering of Linear B is one of our greatest cultural and intellectual achievements bar none. At first, no one knew what language the signs were in, but there are instances of words or configurations of signs with varying endings that suggested an Indo-European language. We can sound out Etruscan with its Latin-like alphabet even though we don’t know the language. Presumably, Etruscan is a non-Indo-European language that we will never be able to understand unless some Rosetta Stone falls into our laps. Linear B has more than seventy different signs, which suggests a syllabic script. Additionally, there are some ideograms, the picture of a jug for “jug” or of a cart with wheels for “cart.” Number signs in a decimal system were rapidly identified. Two questions remained to be answered: What were the sounds made by the different syllabic signs, and what language were the tablets written in? Together, Michael Ventris, an architect and classicist who worked on cracking German Luftwaffe codes during World War Two, used logical grids that grew more complete all the time, and John Chadwick, a classicist and expert in early Ancient Greek dialects, came to the compelling conclusion that it must be an archaic form of Ancient Greek that was perhaps current some seven or eight hundred years before Homer.

Unfortunately, it transpired that the texts were nothing like Homer or Sophocles, not poems at all, but bookkeeping and inventories—who owed how much corn and olive oil to whom and when, what a person’s contribution to a religious festival was, who owed what to which agricultural laborer. Not everything was completely translated and understood, and the earlier Linear A has so far withstood all our efforts to decipher it, presumably because it goes back to a different language that we can’t identify and possibly never will know. My grandfather Rudolf, Michael Ventris, John Chadwick, Oliver Sacks, and, in a lesser way, I, as a gawping bystander, might have made a good team in some fantasy world of magical desires. The Phaistos Disc, a burned clay disc also from Crete, with its spiral inscriptions that exist nowhere else except in a few tiny fragments, is the greatest riddle of all. For me, it’s the emblem of our limitations in reading the world, our mysterious world. Various charlatans claim to have cracked it, but even the biggest supercomputers of the future will never be able to decipher these markings. If someone comes along and declares he has deciphered it, then we may be absolutely certain that he’s a crook. Or a madman.