Illustrious Sir and worshipful patron,

The letter which you were so kind as to send to me three months ago has long remained unanswered, as various impediments have virtually obliged me to remain silent. In particular a long indisposition, or rather, numerous long indispositions, made all other activities and occupations impossible; above all they prevented me from writing, as indeed to a large extent they still do. However, I am not now so constrained that I cannot at least reply to some of the letters from my friends and patrons, of which I have no small number, all awaiting a reply. I have remained silent also because I hoped to be able to give some satisfaction in replying to your enquiry concerning the sunspots, on which topic you have sent me the brief discourses of the writer calling himself ‘Apelles’;* but the difficulty of the subject matter and the fact that I have not been able to make many continuous observations have kept me, and still keep me, undecided and in suspense. I have to be more cautious and circumspect than many others in pronouncing upon anything new because, as you know, my recent observations of things far removed from popular and commonly held views have been violently denied and attacked. So I have to conceal and say nothing about any new idea until I have been able to demonstrate it with the most absolute and palpable proof. The enemies of anything new, of whom there are an infinite number, would pounce on any error I make, however trivial, and make it into a capital fault; for it now seems to be the case that it is better to err with the masses than to be alone in speaking correctly. I might add that I would rather be the last to come out with a true statement than forestall everyone else, only to have to withdraw something that I had put forward with more haste and less reflection.

All these considerations, Sir, have made me slow in responding to your questions, and I still am hesitant to offer anything more than negative statements; for I feel more confident of knowing what the sunspots are not than what they really are, and I find it much harder to discover the truth than to refute what is false. But to satisfy your request at least in part, I shall consider those things that seem to me to be worth pointing out in the three letters of ‘Apelles’, as you ask me to do, as these contain what has been conjectured so far about the essence, location, and motion of these spots.

The sunspots are real; their motion

First of all, I have no doubt that the sunspots are real and not mere appearances or optical illusions, or caused by blemishes in the lenses, as your friend rightly proves in his first letter. I have observed them for the past eighteen months* and have shown them to several of my friends, and last year at precisely this time I had many prelates and other gentlemen in Rome observe them. It is true, too, that they do not remain stationary on the surface of the Sun, but appear to move in relation to it with regular motions, as the author also notes in the same letter. It seems to me, however, that this motion is in the opposite direction to what Apelles asserts; that is, they move from west to east, slanting from south to north, and not from east to west and north to south. This can be clearly seen from the observations which he himself describes, which in this respect agree with my own and with those of others that I have seen. The spots observed at sunset are seen to change place from one evening to the next, moving down from the upper parts of the Sun towards the lower, while those seen in the morning move upwards from the lower parts towards the higher, appearing first in the more southerly parts of the solar surface, and disappear or detach themselves from it in the more northerly parts. Thus the spots describe lines on the face of the Sun similar to those that Venus or Mercury trace when they pass in front of the Sun and interpose themselves between the Sun and our sight. So the spots move with respect to the Sun as do Venus, Mercury, and the other planets, moving, that is, from west to east, and obliquely to the horizon from south to north. If Apelles were to assume that these spots did not revolve around the Sun but simply passed beneath it, then their motion could indeed be described as being from east to west. But if we assume that they describe circles around the Sun, and are alternately in front of it and behind it, then we must describe their revolutions as being from west to east, because this is the direction in which they are moving when they are in the more distant part of their circle.

Having established that the spots he has observed are not illusions caused by the telescope or optical defects, the author next tries to reach some general conclusions about their location, and to show that they are neither in the atmosphere of the Earth nor on the surface of the Sun. As regards the first of these, the absence of any noticeable parallax* necessarily shows that the spots are not in the atmosphere, that is, in the space close to the Earth which is commonly assigned to the element of air. That they cannot be on the surface of the Sun, however, does not seem to me to be entirely demonstrated. His first argument, that it is not credible that there should be dark spots on the surface of the Sun because the Sun is entirely bright, is not valid: for we referred to the Sun as pure and entirely bright as long as no impurities or darkness had been seen on it; but if it is shown to have parts which are impure and stained, why should we not call it spotted and not pure? Names and attributes must be accommodated to the reality of things, not the other way round; things existed before names. His second argument would be conclusive if these spots were permanent and unchanging; but I will discuss this further below.

The spots are no less bright than the light parts of the Moon

What Apelles says next, namely that the spots that are visible on the Sun are much darker than any that have ever been seen on the Moon, seems to me to be absolutely false. On the contrary, I think that the spots seen on the Sun are not just less dark than the dark spots we see on the Moon, but that they are no less bright than the brightest parts of the Moon even when it is directly illuminated by the Sun. The reason for this is as follows. When Venus appears as an evening star, when it is at its most resplendent, it can only be seen when it is many degrees distant from the Sun, especially if both are well above the horizon. This is because the parts of the aether around the Sun are no less bright than Venus itself. From this we can deduce that if we could place the Moon alongside the Sun, even when it is resplendent with light as it is at the full Moon, it would also be invisible, as it would be placed in a field no less bright than itself. Now consider, when we look at the brilliance of the Sun’s disc through a telescope, or eyeglass, how much more resplendent it is than the area around it; and then compare the darkness of the sunspots with both the light of the Sun itself and the darkness of the surrounding area. Both comparisons will show that the spots on the Sun are no darker than the area around it. If, then, the sunspots are no darker than the field surrounding the Sun; and if, moreover, the light of the Moon would be invisible against the brightness of this same area; then it necessarily follows that the sunspots are no less bright than the brightest parts of the Moon, even though they appear shadowy and dark against the brilliant brightness of the solar disc itself. And if they yield nothing in brightness to the lightest parts of the Moon, we can imagine how they would compare with the darkest spots on the Moon’s surface—especially when we recall that these dark areas are caused by the shadows cast by the lunar mountains, and that they stand out in contrast to the illuminated parts no less than the ink against this sheet of paper. I say this not so much to contradict Apelles as to show that we need not assume the material of the sunspots to be very dense and opaque, as we may reasonably suppose the material of the Moon or the other planets to be. A density and opacity similar to those of a cloud is enough, when interposed between us and the Sun, to produce the required obscurity and darkness.

The material of the sunspots is not very dense

The author’s observations show that Venus is horned, and of variable size

Apelles goes on to suggest that this could be a means of establishing with certainty whether Venus and Mercury revolve around the Sun or between the Earth and the Sun, a point which he develops more fully in his second letter. I am somewhat surprised that he has not heard, or, if he has, that he has not made use of the exquisite and convenient method of determining this which I discovered almost two years ago, and which has been communicated to so many people that it is now generally known, and which can be applied on many occasions. This is the fact that Venus changes its shape in the same way as the Moon. If Apelles will now observe Venus with his telescope, he will see that it is perfectly circular and very small, although not as small as it was when it first appeared in the evening. If he continues to observe it he will see that, at the point of its greatest elongation from the Sun, it appears semicircular, after which it will change into a horned shape, becoming thinner as it approaches the Sun again. Around its conjunction with the Sun it will be as thin as the Moon when it is two or three days old, and its visible circle will be so much increased that its apparent diameter, when it rises as an evening star, is less than a sixth of what it appears when it sets in the evening or rises in the morning. Hence its disc appears almost forty times larger in the latter position than in the former. These things leave no room for doubt about the orbit of Venus, but show with absolute certainty that it revolves around the Sun, which is the centre of the revolutions of all the planets, as the Pythagoreans and Copernicus maintain.* Hence there is no need to wait for bodily conjunctions* to confirm such a self-evident conclusion, or to produce arguments which are open to objections, however feeble, to gain the assent of those whose philosophy is strangely unsettled by this new structure of the universe. For these people, if they are not constrained by other evidence, will say either that Venus shines with its own light, or that it is of a substance that can be penetrated by the Sun’s rays, so that it may be illuminated not just on its surface but also in depth. They will shield themselves with this response all the more boldly because there has been no lack of philosophers and mathematicians who have believed this to be the case (pace Apelles, who writes otherwise). Copernicus himself had to admit that one of these propositions was possible, indeed necessary, since he was unable to explain how it was that Venus does not appear horned when it is below the Sun; and indeed no other reply was possible until the telescope came to show us that Venus is naturally dark like the Moon, and that it changes its shape as the Moon does.

I have, however, another major doubt about Apelles’ investigations. He attempts to see Venus against the disc of the Sun when they are in conjunction, expecting it to appear as a much larger spot than any that has been seen so far, since he takes its diameter to be three minutes of an arc, and therefore its surface to be just over a hundred-and-thirtieth part of that of the Sun. This, with respect, is incorrect: the visible diameter of Venus was less than the sixth part of a minute, and its surface less than one forty-thousandth of that of the Sun, as I have established by direct observation and as I will make plain to all in due course. So you can see how much scope there would still be for those who continue to insist with Ptolemy that Venus is lower than the Sun, for they could say that it would be impossible to see such a small speck against the Sun’s immense and brilliant surface. Finally, I would add that such an observation would not necessarily convince those who deny that Venus revolves around the Sun, as they could always fall back on saying that its orbit is above the Sun’s, and indeed they could claim Aristotle’s authority for saying so. Thus, it is not enough for Apelles to show that Venus does not pass below the Sun in their morning conjunction, if he cannot also show that it does pass below the Sun in their evening conjunction. Such bodily conjunctions in the evening are extremely rare, and we will not be able to see one. So Apelles’ argument is not sufficient for his purpose.

Venus is very small in comparison with the Sun

I come now to the third letter of Apelles, in which he deals specifically with the position, motion, and substance of these spots, and concludes that they are stars close to the surface of the Sun, and that they revolve around it in the same way as Mercury and Venus.

The spots are not permanent

To determine their place, he begins with a proof that they are not on the surface of the Sun, in which case their motion would be explained by the Sun’s turning on its axis, because their 15-day passage across the visible hemisphere would then reappear in the same pattern every month; and this does not happen. This argument would be conclusive provided we could first be sure that the spots are permanent, that is, that new ones do not appear while others are erased and vanish; but once it is admitted that some spots are formed and others disintegrate, then it can be argued that the Sun turning on its axis carries them around without necessarily showing us the same spots, or in the same order, or having the same shape. Now I think it would be difficult, indeed impossible and contrary to the evidence of our senses, to prove that they are permanent. Apelles himself must have seen some of them appear for the first time well within the Sun’s circumference, and others fade and vanish before they have finished crossing the Sun, as I too have observed on many occasions. So I neither affirm nor deny that the spots are located on the Sun; I simply state that it has not been sufficiently proved that they are not.

The author goes on to argue that the spots are not in the atmosphere, or in any of the orbs below that of the Sun; and here I find some confusion, not to say inconsistency, for he returns to the old, commonly accepted Ptolemaic system as if it were true, having earlier shown he was aware that it was false. He concluded that Venus does not have an orbit below that of the Sun but revolves around it, as it is sometimes above the Sun and sometimes below it; and he stated the same of Mercury, whose maximum elongation is much smaller than that of Venus and which therefore must be placed closer to the Sun. But then he appears to reject the arrangement which he had earlier accepted as true, as indeed it is, and to adopt the false one; for he places Mercury after the Moon, followed by Venus. I was inclined at first to excuse this small contradiction by saying that he thought it insignificant whether, after the Moon, he named Mercury or Venus first, on the grounds that it did not matter in which order they were named as long as he knew their correct order in reality. But then he undermined my excuse for him by arguing on the basis of parallax that the sunspots are not in the sphere of Mercury, and then adding that this method would not apply to Venus because of its small parallax, which is like that of the Sun; whereas Venus can sometimes have a parallax much greater than those of either Mercury or the Sun.

It seems to me, therefore, that Apelles has a free and not a servile mind; he is well able to grasp true teaching, and now, prompted by the strength of so many new ideas, he is beginning to listen and to assent to true and sound philosophy, especially as regards the arrangement of the universe. But he is not yet able to detach himself completely from the fantasies he absorbed in the past, and to which his intellect sometimes returns and lends assent by force of long-established habit. This is apparent again when, in this same passage, he tries to prove that the spots are not in any of the orbs of the Moon, Venus, or Mercury. In doing so, he continues to adhere to eccentrics, deferents, equants, epicycles, etc.,* as, wholly or in part, real and distinct entities, which were merely assumed by mathematical astronomers to facilitate their calculations. These are not retained by philosophical astronomers whose aim is not just to preserve the appearances by any means, but to investigate the true arrangement of the universe—the greatest and most marvellous problem of all. Such an arrangement exists, and is unique, true, real, and could not possibly be otherwise; and its grandeur and nobility are such that it is worthy to be given pride of place above all other scientific questions by those who think about such matters.

[ ... ]

The material of the sunspots may be unknown and unknowable to us

It remains for us to consider Apelles’ conclusion concerning the essence and the substance of these spots, which, briefly stated, is that they are neither clouds nor comets, but stars which circle around the Sun. On this point I confess that I am not yet sufficiently confident to be able to reach or state any firm conclusion. What I am certain of is that the substance of the spots could be any one of a thousand things which are unknown and unknowable to us, and that the phenomena which we discern in them—their shape, their opacity, and their motion—commonplace as they are, give us little or no general information about them. So I do not think any philosopher could be blamed for confessing that he did not know, and had no means of knowing, the material of which the sunspots are made. If, however, we were to put forward some suggestion of what they might be, based on a degree of analogy with materials that are familiar to us, my opinion would be the very opposite of what is proposed by Apelles. They do not seem to me to have any of the essential qualities which define a star; whereas in contrast, all the qualities which I find in them can be said to be similar to those which we see in our clouds. This can be explained as follows.

Similarity between the sunspots and our clouds

Sunspots are formed and disintegrate in longer or shorter periods of time; some condense and others expand greatly from one day to the next; they change their shape, the majority of them being completely irregular, and they can be darker in one part than another. Being either on or very close to the surface of the Sun, they must necessarily be of enormous bulk. Their uneven opacity means that they can block out more or less of the light from the Sun; and they are sometimes found in great numbers, sometimes few, and at other times none at all. Now where in our experience do we find shapes of enormous bulk which are produced and dissolved in a short time; which last sometimes for a long time, sometimes hardly at all; which expand and contract, easily change their shape, and are more dense and opaque in some parts than others, if not in the clouds? In fact, no other material comes close to meeting all these conditions. And there can be no doubt that if the Earth shone with its own light and did not receive external light from the Sun, it would have a similar appearance to anyone who could observe it from a great distance: as first one region and then another was obscured by clouds, it would appear covered with dark spots which, depending on their greater or lesser density, would block out more or less of the terrestrial splendour, and so they would appear more or less dark; they would appear to be now more numerous, now less, now expanding, now contracting; and if the Earth turned on its axis they would also follow its motion. Since clouds are not very deep in comparison to the breadth to which they commonly expand, those at the centre of the visible hemisphere would appear quite broad, while those nearer the edges would look narrower. In short, I do not think there would be anything in their appearance which is not likewise seen in sunspots. However, since the Earth is dark and receives its light externally from the Sun, an observer looking at it from a great distance would not see any dark spots caused by the distribution of the clouds, because the clouds too would receive and reflect the light of the Sun.

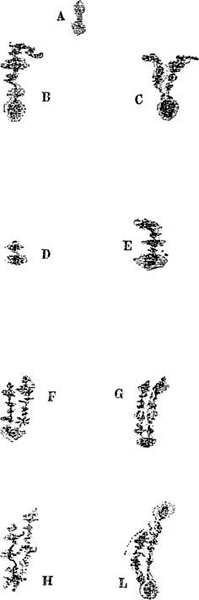

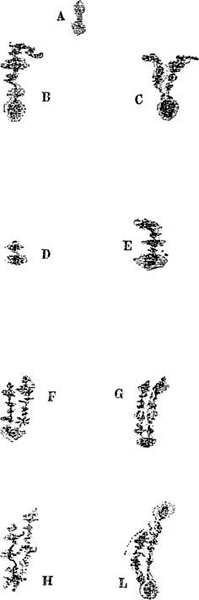

I offer you now these two examples of the changing shape, the irregularities, and the differing densities of sunspots.

Observations of the changes in the density and shape of sunspots, and their irregularity

Spot A was observed at sunset on 5 April last, and was seen to be very faint and not very dark. The following day, also at sunset, it appeared as spot B, having become darker and having changed shape. On 7 April its appearance was similar to figure C. These spots were always well away from the circumference of the Sun.

On 26 April, at sunset, there began to appear in the upper part of the Sun’s circumference a spot similar to D. On 28 April it appeared similar to E, on the 29th to F, on the 30th to G, on 1 May to H, and on 3 May to L. All the changes in F, G, H, and L occurred well away from the circumference of the Sun, so that their changed appearance cannot be explained by the different aspect they would have when close to the circumference, when the surface of the globe is moving.

It is clear from these and other observations that I have made, and from others that can be made day by day, that no material known to us has as many of the properties of the sunspots as do clouds; and the arguments put forward by Apelles to the contrary seem to me to carry little weight. To his question ‘Who would ever place clouds around the Sun?’, I would reply, ‘Anyone who saw these spots and wanted to say something plausible about their nature, for nothing known to us more resembles them.’ When he asks how big they are, I would reply, ‘As big as we see them to be in comparison with the Sun; as big as those clouds that sometimes cover a whole region of the Earth’—or if that is not enough, then I would say two, three, four, or ten times as big. Finally, to the third ‘impossibility’ which he adduces—how they could produce such dark shadows—I would reply that they are less dark than the thickest of our clouds would appear if they were interposed between the Sun and our eyes. This can be clearly seen when one of our darkest clouds covers part of the Sun, and one of the sunspots can be seen in the part that remains visible: it will be clear that there is a significant difference in darkness between the two, even though the edge of the cloud crossing the Sun cannot be very deep. From this it can be deduced that a really thick cloud would produce a much darker shadow than the darkest of the spots. And even if that were not the case, what reason is there to think that some of the solar clouds could not be thicker and denser than terrestrial ones?

This is not to say that I consider sunspots to be clouds of the same material as ours, which are made up of water vapour drawn up from the Earth and attracted by the Sun; I say only that there is nothing of which we have knowledge that more resembles them. Whether they are vapours, or exhalations, or clouds, or fumes produced by the body of the Sun or attracted to it from elsewhere, I have no idea, for they could be any of a thousand other things which are imperceptible to us.

It is not appropriate to call the sunspots ‘stars’

It follows that the term ‘stars’ is not appropriate for these spots. Stars, whether fixed or wandering, are seen always to maintain the same shape, that of a sphere; we do not see some disintegrating and others forming, but they always remain the same; and their motions are periodic, returning after a fixed interval of time. We do not see the spots returning unchanged; on the contrary, we can sometimes see them disintegrate on the Sun’s surface, and I believe one would wait in vain to see the return of the spots which Apelles thinks may revolve in very close orbits around the Sun. In short, they lack the main qualities of those natural bodies to which we give the name of stars. Nor should the spots be called stars because they are opaque bodies, denser than the material of the sky and blocking the rays of the Sun, so that they are illuminated on the side exposed to the Sun’s rays and cast a dark shadow on the other; for these are qualities which apply to a stone or a piece of wood, or to a dense cloud, in short to any opaque body. A piece of marble is opaque and therefore blocks the light of the Sun, which it reflects on one side, as the Moon and Venus do, casting a shadow on the other side. On these grounds it could also be called a star; but since it lacks other and more essential properties of a star, as do the sunspots, the name of star seems inappropriate.

I would have preferred it if Apelles had not put the companions of Jupiter (by which I assume he means the four Medicean planets) in the same category, for they show themselves to be constant like any other star. They shine constantly, except when they pass into Jupiter’s shadow, when they are eclipsed, like the Moon in the Earth’s shadow. They each have their own distinct and orderly period, which have been exactly determined by me; and they do not move in a single orbit, as Apelles seems to believe or to think that others believe, but they have their own distinct orbits with Jupiter as their centre, each of a different size, which I have also discovered. I have likewise detected the reasons why and when one or another of them occasionally tilts towards the north or the south in relation to Jupiter; and I may be able to reply to the objections which Apelles hints that he has on this subject when he specifies what they are. Apelles says he is sure that there are more of these planets than the four which have been observed so far: he may well be right, and such a confident statement by someone who appears to understand the subject very well makes me think that he must have some great new theory which I lack. So I will not be so bold as to say anything definite now, in case I should have to retract it later.

The Medicean planets are constant; they are subject to eclipse; they have fixed periods which have been discovered by the Author.

They each move in their own distinct orbit

Description of stars alongside Saturn discovered by the Author.

Differences in the appearance of Saturn caused by defective vision

For the same reason, I am reluctant to place anything around Saturn except what I have already observed and discovered: namely, that there are two small stars touching it, one on the east side and the other on the west, which have not so far shown any change, and which I am confident will not show any in the future, barring some extraordinary event quite remote from any motion known to us or even which we could imagine. As regards Apelles’ suggestion that Saturn is sometimes oblong in shape and sometimes accompanied by two stars alongside it, I assure you that this is due to an imperfection either in the instrument or in the eye of the observer. The shape of Saturn appears thus,  as can be seen when vision and instruments are both perfect. Where vision is impaired it appears thus,

as can be seen when vision and instruments are both perfect. Where vision is impaired it appears thus,  the separation and shape of the three stars being indistinct. I have observed Saturn at many different times with an excellent instrument and I can assure you that no change whatever has been found in it; and reason, based on our experience of all other stellar motions, renders us certain that none will be found in the future.* For if there were indeed any motion in these stars that was similar to those of the Medicean planets or other stars, they would by now either be separated from or completely conjoined to the body of Saturn, even if their motion had been a thousand times slower than that of any other star that wanders in the heavens.

the separation and shape of the three stars being indistinct. I have observed Saturn at many different times with an excellent instrument and I can assure you that no change whatever has been found in it; and reason, based on our experience of all other stellar motions, renders us certain that none will be found in the future.* For if there were indeed any motion in these stars that was similar to those of the Medicean planets or other stars, they would by now either be separated from or completely conjoined to the body of Saturn, even if their motion had been a thousand times slower than that of any other star that wanders in the heavens.

Apelles puts forward, in conclusion, the suggestion that the spots are planets rather than fixed stars, and that there is a great number of them between the Sun, Mercury, and Venus, of which only those which are interposed between us and the Sun are visible to us. To this I respond, as regards the first part, that I do not believe that they are stars, either wandering or fixed, or that they move around the Sun in circles separate and at some distance from it. If I were to give my own opinion in confidence to a friend and patron, I would say that the sunspots are produced and disintegrate upon the surface of the Sun, with which they are contiguous, and that they are carried along by the motion of the Sun itself, as it turns on its axis in about one lunar month. Some which last for longer than the Sun’s rotation period may reappear, but they are so changed in their shape and configuration that it is hard for us to recognize them. This is as far as I am able to conjecture at present, and I hope that you will consider the matter closed with what I have said here.

The sunspots are not stars; what the Author believes them to be

Only few stars can be between the Sun and Mercury, and between Mercury and Venus

As regards the possibility that there could be another planet between the Sun and Mercury, which goes around the Sun but is invisible to us because its digressions from the Sun are very small, and because it would become visible to us only if it passed directly across the face of the Sun, this seems to me not at all improbable. In fact, I find it equally credible that such planets may exist or that they may not. I do not think there can be a large number of them, however, because if there were it would be reasonable to expect that we would frequently see one of them between us and the Sun, and thus far I have not seen any; in fact I have not seen anything apart from the spots themselves. It is not likely that any such star should have passed across the Sun’s surface in the form of a dark spot, for if it did, its motion would have to be uniform, and very much faster than that of the spots. It would have to be much faster because it would have a smaller orbit than that of Mercury, and if its motion were analogous to that of all the other planets, its orbital period would have to be shorter than Mercury’s. Now Mercury passes across the Sun’s disc in approximately six hours, so a planet which moves more quickly could not remain in conjunction with the Sun for longer than this—unless it were assumed that its orbit was so small that it almost touched the Sun’s surface, which seems highly fanciful. But if its orbit was two or three times the diameter of the Sun the effect would be as I have described, whereas the sunspots remain in conjunction with the Sun for many days; so it is not credible that a planet should be among them, or should appear like them. Moreover, apart from its velocity, the motion of a planet would have to be almost uniform, even if it were a significant distance from the Sun, because only a small part of its revolution would be across the Sun, and that small part would be directly and not obliquely visible to our sight. So any inequality in the angle at which it was visible to us would be so imperceptible as to be virtually equal, with the result that its motion would appear to be uniform. But the motion of the spots is not like this, as they pass quickly across the middle part of the Sun and slow down when they approach the circumference. So there could only be a small number of planets between the Sun and Mercury, and fewer still between Mercury and Venus; for they would necessarily have a maximum digression greater than that of Mercury, and so, like Venus and Mercury itself, they would have to be brightly visible, especially as they would be relatively close to the Sun and the Earth. Both their closeness to us and the effective illumination of the Sun would mean that they shone so brightly that they would be visible despite their small size.

I recognize that I have taxed your patience, Sir, by writing at such length and so inconclusively. Please take my long-windedness as a sign of the pleasure I have in speaking to you and my desire to oblige you, as far as my powers permit; and so pardon my excessive loquacity, and accept the warmth of my affection. Let my inconclusiveness be excused by the novelty and difficulty of the subject matter; for so many different thoughts and opinions have gone through my mind, some gaining my assent, others provoking rejection and contradiction, that I have become so timid and uncertain that I hardly dare open my mouth to pronounce on anything at all. This does not mean that I intend to give up and abandon the task; I hope rather that these new ideas may serve a wonderful purpose in enabling me to tune some pipes in this great discordant organ which is our philosophy. For I see many organists striving in vain to bring it into perfect harmony, which they cannot because they ignore three or four of the principal pipes and leave them discordant, so that it is impossible for the others to harmonize with them.

I hope that, as your servant, I may share the friendship you have with Apelles, who seems to me a person of great intelligence and a lover of the truth. Therefore I beg you to greet him warmly in my name, and to tell him that in a few days I shall send him some observations and drawings of the sunspots, made with absolute accuracy as regards both their shape and their changing location from day to day. They are drawn without a hairsbreadth of error, using a highly refined method discovered by a pupil of mine,* and I hope they may be of use to him in his further theorizing about their nature.

I must presume on your patience no longer; so I kiss your hand with all reverence and commend myself to your kind favour, praying that God may grant you all happiness.

From the Villa delle Selve, 4 May 1612.

Your devoted servant,

Galileo Galilei, Lincean Academician.

There are not a few Aristotelian philosophers on this side of the Alps who do not pursue philosophy from a desire to know the truth and its causes, for they deny all these new discoveries without distinction and dismiss them as illusions. Now I think it is time for us to dismiss them in their turn, treating them as both invisible and inaudible. They seek to defend the immutability of the heavens which Aristotle himself, if he were alive today, might well abandon. I understand that an opinion is circulating among them which is similar to that of Apelles, except that where he supposes a single star for each spot, they make the spots clusters of very small stars whose different motions make them agglomerate in greater or smaller numbers and then separate again, thus forming larger or smaller spots of irregular and varying shapes.* Since I have already gone well beyond the bounds of brevity in this letter, so that you will have to read it in more than one sitting, I shall take the liberty of offering some comments on this point.

The opinion that the sunspots are clusters of very small stars, examined and refuted

My first reaction is that those who uphold this opinion cannot have had the opportunity to make careful or prolonged observations, for I am sure that they would have encountered several difficulties in working out how to accommodate their view to the phenomena. For while it is generally true that a large number of objects which are too small and distant to be visible individually can, when joined together, form an agglomeration which is visible to our sight, nonetheless we need to go beyond the general rule and take account of the specific properties of stars and what we observe in the spots, and then consider carefully how far they could join together. We should not act like the defender of a castle who rushes with all his small number of soldiers to defend some point which he sees under attack and leaves other parts exposed and undefended. In the same way, when trying to defend the immutability of the heavens, we should not neglect the other perils to which other propositions, just as necessary for the preservation of Aristotelian philosophy, might be exposed. So the first point to be noted if the integrity and solidity of this philosophy is to be maintained is that stars are of two kinds, fixed and wandering. The fixed stars are those which are all in one sphere and move with its motion while remaining unmoved in relation to each other, while wandering stars are those which each have their own individual motion.* Moreover, the motions of both kinds of star must be constant, since it would not be appropriate for the intelligences which move them to have to exert themselves more at some times than at others, which would be inconsistent with their own nobility and unchangeability as well as that of the spheres. With this in mind, first, we cannot say that these ‘solar stars’ are fixed, because if they did not move in relation to each other it would be impossible to see the continual changes we observe in the spots, and they would always reappear in the same configurations. So they would have to be wandering stars, each with its own motion which is different from all the others but constant in itself. This would explain how some of them collide and separate, but not how they can form spots, as will be clear if we consider some of the things that are observed in the spots. One is that we see some very large spots appear and disintegrate. These must perforce be made up not of two or three stars but of fifty or a hundred, because there are other smaller spots which are less than a fiftieth of the size of the large ones. So if one of the large ones disintegrates so as to disappear completely from our sight, it must divide into at least fifty small stars, each with its own specific motion which is constant and different from all the others, because two with the same motion would never combine or separate on the Sun’s surface. If all this is true, surely it is absolutely impossible for spots to form—especially if they last not just for many hours but for many days—just as it would be impossible for fifty boats all moving at different speeds to join and move together for a long space of time? If, on the other hand, these small stars were separate and therefore invisible, they would have to be strung out one behind the other in long lines, according to the length of the parallels at which they are, all travelling in the same direction, as can be seen with the visible sunspots. But then, far from forty, fifty, or a hundred of them being able to come together so frequently and stay together for such long stretches of time, it would be very rare for so many unequal motions to bring such a large number of stars together in one place at all—and if they did they would inevitably disperse again almost immediately. But as we have seen, many spots can remain for many days at a time with very little change in their shape. To maintain, therefore, that the sunspots are clusters of very small stars requires introducing into the heavens and the stars innumerable motions which would be chaotic, unrelated, and completely irregular, something which is not compatible with any plausible philosophy.

What is more, we would have to suppose that these small stars are more numerous than all the other visible stars put together; for if we consider the number and size of all the spots that have been seen over time on the surface of the Sun, and then break them down into particles so small that they cannot be seen, it will be clear that there must be many hundreds of them. And since it is reasonable to suppose that there must be others not only behind the Sun but on either side of it as well, it is hard to escape the conclusion that there must be more than a thousand. But how then could we maintain some proportion between the distances of the wandering stars and their orbital periods, if between the huge orbit of Saturn and the very small one of Mercury we find only ten or twelve stars and not more than six different orbital periods around the Sun, and we now have to find room for hundreds and thousands more within such a small sphere? They would all be contained within the limits of the revolution of Mercury, because they never shine visibly as stars away from the Sun. But why say that they must be within the sphere of Mercury, when we have already seen that the spots must necessarily be either on the surface or at an imperceptible distance from the surface of the Sun? So anyone who would have us believe that the sunspots are clusters of very small stars must first find a way of convincing us that there are many hundreds of dark, dense globes revolving over the Sun’s surface, all at different speeds, often colliding and blocking each other’s way, so that the course of the fastest is held back for days at a time by the speed of the slowest; and that in this great crowd there frequently form distinct groups, big enough to be visible to us, until the pressure of the throng coming along behind breaks them up and disperses them to force its way through.

What lengths the advocates of this position have to go to—and how effectively do they demonstrate it, and to what purpose? To keep celestial matter untainted by the condition of the elements, even down to the smallest change. If what is known as ‘corruption’ was equivalent to annihilation, then the Aristotelians would have good reason to be so resistant to it; but it hardly deserves such hostility if it is nothing more than change. It seems unreasonable to me to call ‘corruption’ in an egg that which produces a chicken. In any case, if what we call generation and corruption are no more than a tiny mutation in a small part of the elemental world, which cannot be seen even from the Moon, close as it is, why should we deny that it can take place in the heavens? Do they imagine, arguing from the part to the whole, that the Earth itself is going to disintegrate and decay, so that there will come a time when the universe will have the Sun, the Moon, and the other stars, but not the Earth? I do not believe that they have any such fear. So if the Earth’s small mutations do not threaten it with total destruction, and indeed are an adornment to it rather than a defect, why should we deny that they occur elsewhere in the universe, or fear that the heavens might disintegrate because of changes no more damaging to the preservation of nature than these? I suspect that our wish to measure everything by our own small standards leads us into strange fantasies, and that our special hatred of death makes the thought of fragility odious to us. But would we really want to escape from mutability by encountering a Medusa’s head which would turn us into a block of marble or a diamond, depriving us of our senses and all the other qualities which we could not experience if we did not undergo bodily change?

Such collisions and crowding together of stars would be absurd

Change is not alien to the heavens,* or prejudicial to them

I do not wish to go further now in examining the strength of the Aristotelians’ arguments, which I hope to do on another occasion. I would simply add that it seems to me not entirely worthy of a true philosopher to persist obstinately, if I may say so, in defending Aristotelian positions which have clearly been shown to be false, perhaps in the belief that Aristotle himself would do the same if he were living in our own time—as if it were more a sign of clear judgement and great learning to defend a false position than to be persuaded of the truth. I cannot help wondering whether those who act in this way are less interested in weighing the strength of the arguments for and against the Aristotelian position than in maintaining the authority of Aristotle himself, as a much easier way of fending off any dangerous arguments, given that citing and comparing texts is so much easier than investigating truth and formulating new and conclusive proofs. It seems to me, indeed, that we are selling ourselves short and showing disrespect for nature and even for divine Goodness (who to help us understand his great creation has given us two thousand more years of observations and sight twenty times more acute than Aristotle’s), if we now attempt to learn from Aristotle what he had no means of knowing rather than relying on the evidence of our own eyes and our own reason. But as I do not want to stray any further from my main intention, I am content for now to have demonstrated that the sunspots are neither stars nor permanent materials, and that they are not located at a distance from the Sun, but that they are produced and disintegrate upon it in a way not unlike clouds and other vapours around the Earth.

Those who do not straightforwardly follow the truth in philosophy deserve great blame

Conclusion

The author’s tables for calculating the motions of the Medicean planets

This was all I had to say to you, Sir, on this matter, for the present, as I imagined that this would set the seal on all my new discoveries in the heavens, and that I could now have leisure to return uninterrupted to my other studies. I have already succeeded, after long and painstaking researches, in establishing the periodicity of all four of the Medicean planets, and drawn up tables for calculating their motions and their individual features; and I shall shortly publish these, together with my considerations on the other celestial discoveries. But my expectations were confounded by an unforeseen marvel which has recently come to concern me regarding Saturn, of which I shall give you an account.

I have already written* of my discovery about three years ago that, to my great astonishment, Saturn is three-bodied: that is, it is an agglomeration of three stars arranged in a straight line parallel to the ecliptic, the central star being much larger than those on either side. I believed that they were fixed in relation to each other, which was not unreasonable given that they had remained without any apparent change for more than two years since I had first observed them, so close that they seemed almost to be touching. It was hardly surprising that I considered their relative positions to be completely fixed, as even a single second of an arc—a motion incomparably smaller than any other motion even in the largest spheres—would have become apparent in that time, either by separating or completely uniting these three stars. Saturn still appeared with its threefold body when I observed it this year, about the time of the summer solstice, after which I did not observe it again for more than two months, as I was quite sure that it did not change. But when I came to observe it again in the last few days I found it unaccompanied, without its usual companion stars, and perfectly round and sharply bounded like Jupiter; and so it still remains. What can we make of such a strange metamorphosis? Have the two smaller stars disintegrated like the sunspots? Have they disappeared and suddenly fled? Has Saturn devoured its children?* Or was their original appearance an illusion produced by the lenses, which deceived me for so long, as well as the many others who observed it with me on many occasions? Is this the moment to revive the fading hopes of those whose profound learning has enabled them to see through all the new discoveries and pronounce them to be fallacies that could not possibly exist? I have no firm conclusion to offer on such a strange and unexpected development: lack of time, the unprecedented nature of the event, my limited understanding, and a fear of error all add to my uncertainty.

A new and unexpected marvel concerning Saturn.

Saturn without its accompanying stars

But let me be rash for once, and I hope that you will pardon my rashness since I confess it as such. I do not put forward what I am about to say as something based on established principles and secure conclusions, but simply on plausible conjectures,* which I will publish when I need either to show why the opinion to which I now incline was justifiable, or to confirm my position if I should prove to be correct. So my propositions are these: that the two smaller stars of Saturn, which at present are hidden, are likely to reveal themselves a little for about two months around the time of the summer solstice next year, 1613. They will then disappear, and will remain hidden until the winter solstice of the year 1614. They may well be visible again for a few months during that period, but they will disappear again close to the winter solstice. I am more confident that they will reappear at that time and will remain visible thereafter, although at the following summer solstice, in 1615, they will begin to conceal themselves again; but I do not believe that they will disappear altogether, but that after a short time they will show themselves again, and we shall be able to see them not only distinctly, but brighter and bigger than ever. Then, I dare to say with confidence that they will remain visible to us for many years without any interruption at all. I have no doubt that they will return, and so I am cautious in asserting any other specific details, which for now are based only on probable conjecture. But I say with all confidence that, whether their motions turn out as I have described or otherwise, this star will, perhaps no less than the horned appearance of Venus, agree marvellously with the great system of Copernicus, which we can see to be set fair to gaining universal acceptance, so that there is now little fear of its being blown off course.

Conjectures on the future mutations of Saturn