7

Eradicating Poverty, Stabilizing Population

The new century began on an inspiring note when the countries that belong to the United Nations adopted the goal of cutting the number of people living in poverty in half by 2015. And as of 2007 the world looked to be on track to meet this goal. There are two big reasons for this: China and India. China’s annual economic growth of nearly 10 percent over the last two decades, along with India’s more recent acceleration to 7 percent a year, have together lifted millions out of poverty.1

The number of people living in poverty in China dropped from 648 million in 1981 to 218 million in 2001, the greatest reduction in poverty in history. India is also making impressive economic progress. Under the dynamic leadership of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who took office in 2004, poverty is being attacked directly by upgrading infrastructure at the village level. Targeted investments are aimed at the poorest of the poor.2

If the international community actively reinforces this effort in reform-minded India, hundreds of millions more could be lifted out of poverty. With India now on the move economically, the world can begin to concentrate intensively on the remaining poverty concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and in scores of smaller countries in Latin America and Central Asia.

Several countries in Southeast Asia are making impressive gains as well, including Thailand, Viet Nam, and Indonesia. Barring any major economic setbacks, these gains in Asia virtually ensure that the U.N. Millennium Development Goal (MDG) for halving poverty by 2015 will be reached. Indeed, in a 2007 assessment of progress in reaching the MDGs, the World Bank reported that all regions of the developing world, with the notable exception of sub-Saharan Africa, were on track to cut the number living in poverty in half by 2015.3

Sub-Saharan Africa—with 800 million people—is sliding deeper into poverty. Hunger, illiteracy, and disease are on the march, partly offsetting the gains in China and India. Africa needs special attention. The failing states as a group are also backsliding; an interregional tally of the Bank’s fragile states is not encouraging, since extreme poverty in these countries is over 50 percent—higher than in 1990.4

In addition to halving the number of people living in poverty by 2015, other MDGs include reducing the ranks of those who are hungry by half, achieving universal primary school education, halving the number of people without access to safe drinking water, and reversing the spread of infectious diseases, especially HIV and malaria. Closely related to these are the goals of reducing maternal mortality by three fourths and under-five child mortality by two thirds.5

While goals for cutting poverty in half by 2015 appear to be on schedule, those for halving the number of hungry are not. Indeed, the long-term decline in the number of those who are hungry and malnourished has been reversed. The number of children with a primary school education appears to be increasing substantially, however, largely on the strength of progress in India.6

When the United Nations set the MDGs, it unaccountably omitted any population or family planning goals. In response to this, the U.K. All Party Parliamentary Group on Population Development and Reproductive Health chaired by M.P. Christine McCafferty convened hearings of international experts to consider this omission. In a January 2007 report of the findings, M.P. Richard Ottaway concluded that “the MDGs are difficult or impossible to achieve with current levels of population growth in the least developed countries and regions.”7

Summarizing the report’s findings in an article in Science, Martha Campbell and colleagues explained the need for “a substantial increase for support in national family planning, particularly for the 2 billion people currently living on less than $2 per day.” Although it came belatedly, the United Nations has since approved a new target that calls for universal access to reproductive health care by 2015.8

Countries everywhere have little choice but to strive for an average of two children per couple. There is no feasible alternative. Any population that increases or decreases continually over the long term is not sustainable.

In an increasingly integrated world with a growing number of failing states, eradicating poverty and stabilizing population have become national security issues. Slowing population growth helps eradicate poverty and its distressing symptoms, and, conversely, eradicating poverty helps slow population growth. With time running out, the urgency of moving simultaneously on both fronts is clear.

Universal Basic Education

One way of narrowing the gap between rich and poor segments of society is by ensuring universal education. This means making sure that the 72 million children not enrolled in school are able to attend. Children without any formal education are starting life with a severe handicap, one that almost ensures they will remain in abject poverty and that the gap between the poor and the rich will continue to widen. In an increasingly integrated world, this widening gap itself becomes a source of instability. Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen focuses the point: “Illiteracy and innumeracy are a greater threat to humanity than terrorism.”9

In the effort to achieve universal primary education, the World Bank has taken the lead with its Education for All plan, where any country with a well-designed plan to achieve universal primary education is eligible for Bank financial support. The three principal requirements are that a country submit a sensible plan to reach universal basic education, commit a meaningful share of its own resources to the plan, and have transparent budgeting and accounting practices. If fully implemented, all children in poor countries would get a primary school education by 2015, helping them to break out of poverty.10

Some progress toward this goal has been made. In 2000, some 78 percent of children were completing primary school, while by 2005 this figure reached 83 percent. Gains have been strong but uneven, leaving the World Bank to conclude that only 95 of the 152 developing countries for which data are available will reach the goal of universal primary school education by 2015.11

Poverty is largely inherited. The overwhelming majority of those living in poverty today are the children of people who lived in poverty. The key to breaking out of the culture of poverty is education—particularly the education of girls. As female educational levels rise, fertility falls. And mothers with at least five years of school lose fewer infants during childbirth or to early illnesses than their less educated peers do. Economist Gene Sperling concluded in a 2001 study of 72 countries that “the expansion of female secondary education may be the single best lever for achieving substantial reductions in fertility.”12

Basic education tends to increase agricultural productivity. Agricultural extension services that can use printed materials to disseminate information have an obvious advantage. So too do farmers who can read the instructions on a bag of fertilizer. The ability to read instructions on a pesticide container can be life-saving.

At a time when HIV is spreading, schools provide the institutional means to educate young people about the risks of infection. The time to inform and educate children about the virus and about the lifestyles that foster its spread is when they are young, not when they are already infected. Young people can also be mobilized to conduct educational campaigns among their peers.

One great need in developing countries, particularly those where the ranks of teachers are being decimated by AIDS, is more teacher training. Providing scholarships for promising students from poor families to attend training institutes in exchange for a commitment to teach for, say, five years, could be a highly profitable investment. It would help ensure that the teaching resources are available to reach universal primary education, and it would also foster an upwelling of talent from the poorest segments of society.

Gene Sperling believes that every plan should provide for getting to the hardest-to-reach segments of society, especially poor girls in rural areas. He notes that Ethiopia has pioneered this with Girls Advisory Committees. Representatives of these groups go to the parents who are seeking early marriage for their daughters and encourage them to keep their girls in school. Some countries, Brazil and Bangladesh among them, actually provide small scholarships for girls or stipends to their parents where needed, thus helping those from poor families get a basic education.13

As the world becomes ever more integrated economically, its nearly 800 million illiterate adults are severely handicapped. This deficit can best be overcome by launching adult literacy programs, relying heavily on volunteers. The international community could offer seed money to provide educational materials and outside advisors where needed. Bangladesh and Iran, both of which have successful adult literacy programs, can serve as models.14

An estimated $10 billion in external funding, beyond what is being spent today, is needed for the world to achieve universal primary education. At a time when education gives children access not only to books but also to personal computers and the Internet, having children who never go to school is no longer acceptable.15

Few incentives to get children in school are as effective as a school lunch program, especially in the poorest countries. Since 1946, every American child in public school has had access to a school lunch program, ensuring at least one good meal each day. There is no denying the benefits of this national program.16

Children who are ill or hungry miss many days of school. And even when they can attend, they do not learn as well. Jeffrey Sachs of the Earth Institute at Columbia University notes, “Sick children often face a lifetime of diminished productivity because of interruptions in schooling together with cognitive and physical impairment.” But when school lunch programs are launched in low-income countries, school enrollment jumps, the children’s academic performance goes up, and children spend more years in school.17

Girls benefit especially. Drawn to school by the lunch, they stay in school longer, marry later, and have fewer children. This is a win-win-win situation. Launching school lunch programs in the 44 lowest-income countries would cost an estimated $6 billion per year beyond what the United Nations is now spending to reduce hunger.18

Greater efforts are also needed to improve nutrition before children even get to school age, so they can benefit from school lunches later. Former Senator George McGovern notes that “a women, infants and children (WIC) program, which offers nutritious food supplements to needy pregnant and nursing mothers,” should also be available in the poor countries. Based on 33 years of experience, it is clear that the U.S. WIC program has been enormously successful in improving nutrition, health, and the development of preschool children from low-income families. If this were expanded to reach pregnant women, nursing mothers, and small children in the 44 poorest countries, it would help eradicate hunger among millions of small children at a time when it could make a huge difference.19

These efforts, though costly, are not expensive compared with the annual losses in productivity from hunger. McGovern thinks that this initiative can help “dry up the swamplands of hunger and despair that serve as potential recruiting grounds for terrorists.” In a world where vast wealth is accumulating among the rich, it makes little sense for children to go to school hungry.20

Stabilizing Population

Some 43 countries now have populations that are either essentially stable or declining slowly. In countries with the lowest fertility rates, including Japan, Russia, Germany, and Italy, populations will likely decline somewhat over the next half-century.21

A larger group of countries has reduced fertility to the replacement level or just below. They are headed for population stability after large numbers of young people move through their reproductive years. Included in this group are China and the United States. A third group of countries is projected to more than double their populations by 2050, including Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda.22

U.N. projections show world population growth under three different assumptions about fertility levels. The medium projection, the one most commonly used, has world population reaching 9.2 billion by 2050. The high one reaches 10.8 billion. The low projection, which assumes that the world will quickly move below replacement-level fertility to 1.6 children per couple, has population peaking at just under 8 billion in 2041 and then declining. If the goal is to eradicate poverty, hunger, and illiteracy, we have little choice but to strive for the lower projection.23

Slowing world population growth means that all women who want to plan their families should have access to the family planning services they need. Unfortunately, at present 201 million couples cannot obtain the services they need. FormerU.S. Agency for International Development official J. Joseph Speidel notes that “if you ask anthropologists who live and work with poor people at the village level…they often say that women live in fear of their next pregnancy. They just do not want to get pregnant.” Filling the family planning gap may be the most urgent item on the global agenda. The benefits are enormous and the costs are minimal.24

The good news is that countries that want to help couples reduce family size can do so quickly. My colleague Janet Larsen writes that in just one decade Iran dropped its near-record population growth rate to one of the lowest in the developing world. When Ayatollah Khomeini assumed leadership in Iran in 1979, he immediately dismantled the well-established family planning programs and instead advocated large families. At war with Iraq between 1980 and 1988, Khomeini wanted large families to increase the ranks of soldiers for Islam. His goal was an army of 20 million. In response to his pleas, fertility levels climbed, pushing Iran’s annual population growth to a peak of 4.2 percent in the early 1980s, a level approaching the biological maximum. As this enormous growth began to burden the economy and the environment, the country’s leaders realized that overcrowding, environmental degradation, and unemployment were undermining Iran’s future.25

In 1989 the government did an about-face and restored its family planning program. In May 1993, a national family planning law was passed. The resources of several government ministries, including education, culture, and health, were mobilized to encourage smaller families. Iran Broadcasting was given responsibility for raising awareness of population issues and of the availability of family planning services. Some 15,000 “health houses” or clinics were established to provide rural populations with health and family planning services.26

Religious leaders were directly involved in what amounted to a crusade for smaller families. Iran introduced a full panoply of contraceptive measures, including the option of male sterilization—a first among Muslim countries. All forms of birth control, including contraceptives such as the pill and sterilization, were free of charge. In fact, Iran became a pioneer—the only country to require couples to take a class on modern contraception before receiving a marriage license.27

In addition to the direct health care interventions, a broad-based effort was launched to raise female literacy, boosting it from 25 percent in 1970 to more than 70 percent in 2000. Female school enrollment increased from 60 to 90 percent. Television was used to disseminate information on family planning throughout the country, taking advantage of the 70 percent of rural households with TV sets. As a result of this initiative, family size in Iran dropped from seven children to fewer than three. From 1987 to 1994, Iran cut its population growth rate by half. Its overall population growth rate of 1.3 percent in 2006 is only slightly higher than the U.S. growth rate.28

While the attention of researchers has focused on the role of formal education in reducing fertility, soap operas on radio and television can even more quickly change people’s attitudes about reproductive health, gender equity, family size, and environmental protection. A well-written soap opera can have a profound short-term effect on population growth. It costs relatively little and can proceed even while formal educational systems are being expanded.

The power of this approach was pioneered by Miguel Sabido, a vice president of Televisa, Mexico’s national television network, when he did a series of soap opera segments on illiteracy. The day after one of the characters in his soap opera visited a literacy office wanting to learn how to read and write, a quarter-million people showed up at these offices in Mexico City. Eventually 840,000 Mexicans enrolled in literacy courses after watching the series.29

Sabido dealt with contraception in a soap opera entitled Acompáñeme, which translates as Come With Me. Over the span of a decade this drama series helped reduce Mexico’s birth rate by 34 percent.30

Other groups outside Mexico quickly picked up this approach. The U.S.-based Population Media Center (PMC), headed by William Ryerson, has initiated projects in some 15 countries and is planning launches in several others. The PMC’s work in Ethiopia over the last several years provides a telling example. Their radio serial dramas broadcast in Amharic and Oromiffa have addressed issues of reproductive health and gender equity, such as HIV/AIDS, family planning, and the education of girls. A survey two years after the broadcasts began in 2002 found that 63 percent of new clients seeking reproductive health care at Ethiopia’s 48 service centers reported listening to one of PMC’s dramas.31

Among married women in the Amhara region who listened to the dramas, there was a 55-percent increase in those who had used family planning methods. Male listeners sought HIV tests at a rate four times that of non-listeners, while female listeners were tested at three times the rate of female non-listeners. The average number of children born per woman dropped from 5.4 to 4.3. And demand for contraceptives increased 157 percent.32

The costs of providing reproductive health and family planning services are small compared with their benefits. Joseph Speidel estimates that expanding these services to reach all women in the developing countries would take close to $17 billion in additional funding from both industrial and developing countries.33

The United Nations estimates that meeting the needs of the 201 million women who do not have access to effective contraception could each year prevent 52 million unwanted pregnancies, 22 million induced abortions, and 1.4 million infant deaths. Put simply, the costs to society of not filling the family planning gap may be greater than we can afford.34

Shifting to smaller families brings generous economic dividends. For Bangladesh, analysts concluded that $62 spent by the government to prevent an unwanted birth saved $615 in expenditures on other social services. Investing in reproductive health and family planning services leaves more fiscal resources per child for education and health care, thus accelerating the escape from poverty. For donor countries, filling the entire $7.9 billion gap needed to ensure that couples everywhere have access to the services they need would yield strong social returns in improved education and health care.35

Better Health for All

While heart disease and cancer (largely the diseases of aging), obesity, and smoking dominate health concerns in industrial countries, in developing countries infectious diseases are the overriding health concern. Besides AIDS, the principal diseases of concern are diarrhea, respiratory illnesses, tuberculosis, malaria, and measles. Child mortality is high.

Progress in reaching the MDG of reducing child mortality two thirds by 2015 is lagging badly. As of 2005 only 32 of 147 developing countries are on track to reach this goal. In 23 countries child mortality has either remained unchanged or risen. And only 2 of the World Bank’s 35 fragile states are on track to meet this goal by 2015.36

Along with the eradication of hunger, ensuring access to a safe and reliable supply of water for the estimated 1.1 billion people who lack it is essential to better health for all. The realistic option in many cities now may be to bypass efforts to build costly water-based sewage removal and treatment systems and to opt instead for water-free waste disposal systems that do not disperse disease pathogens. (See the description of dry compost toilets in Chapter 10.) This switch would simultaneously help alleviate water scarcity, reduce the dissemination of disease agents in water systems, and help close the nutrient cycle—another win-win-win situation.37

One of the most impressive health gains has come from a campaign initiated by a little-heralded nongovernmental group in Bangladesh, BRAC, that taught every mother in the country how to prepare oral rehydration solution to treat diarrhea at home by simply adding salt and sugar to water. Founded by Fazle Hasan Abed, BRAC succeeded in dramatically reducing infant and child deaths from diarrhea in a country that was densely populated, poverty-stricken, and poorly educated.38

Seeing this great success, UNICEF used BRAC’s model for its worldwide diarrheal disease treatment program. This global administration of a remarkably simple oral rehydration technique has been extremely effective—reducing deaths from diarrhea among children from 4.6 million in 1980 to 1.6 million in 2006. Egypt alone used oral rehydration therapy to cut infant deaths from diarrhea by 82 percent from 1982 to 1989. Few investments have saved so many lives at such a low cost.39

The war against infectious diseases is being waged on a broad front. Perhaps the leading privately funded life-saving activity in the world today is the childhood immunization program. In an effort to fill the gap in this global program, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invested more than $1.5 billion through 2006 to protect children from infectious diseases like measles.40

Additional investment can help the many countries that cannot afford vaccines for childhood diseases and are falling behind in their vaccination programs. Lacking the funds to invest today, these countries pay a far higher price tomorrow. There are not many situations where just a few pennies spent per youngster can make as much difference as vaccination programs can.41

One of the international community’s finest hours came with the eradication of smallpox, an effort led in the United Nations by the World Health Organization (WHO). This successful elimination of a feared disease, which required a worldwide immunization program, saves not only millions of lives but also hundreds of millions of dollars each year in smallpox vaccination programs and billions of dollars in health care expenditures. This achievement alone may justify the existence of the United Nations.42

Similarly, a WHO-led international coalition, including Rotary International, UNICEF, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Ted Turner’s UN Foundation, has waged a worldwide campaign to wipe out polio, a disease that has crippled millions of children. Since 1988, Rotary International has contributed an extraordinary $600 million to this effort. Under this coalition-sponsored Global Polio Eradication Initiative, the number of polio cases worldwide dropped from some 350,000 per year in 1988 to fewer than 700 in 2003.43

By late 2007, only 10 countries were still reporting polio cases, including Afghanistan, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, and several countries in central Africa and the Horn of Africa. The number of cases reported worldwide dropped from roughly 2,000 in 2006 to 545 during the first nine months of 2007. A reinvigorated program in Nigeria was on the verge of eradicating polio there.44

For the coalition, the prospect of total eradication was within its grasp. But once again, hard-line clerics, this time in a remote region of Pakistan, began saying that the vaccination program was a U.S. conspiracy to render people infertile. Health workers have been attacked and driven from parts of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province where the polio virus still exists. Two workers have been killed. A small group of people refusing to cooperate with the initiative could prevent the eradication of this dreaded disease for all time.45

One of the more remarkable health success stories is the near eradication of guinea worm disease (dracunculiasis), a campaign led by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center. These worms, whose larvae are ingested by drinking unfiltered water from lakes and rivers, mature in a person’s body, sometimes reaching more than two feet in length, and then exit slowly through the skin in a very painful and debilitating ordeal that can last several weeks.46

With no vaccine to prevent infection or drug for treatment, eradication depends on filtering drinking water to prevent larvae ingestion, thus eradicating the worm, which can survive only in a human host. Six years after the CDC launched a global campaign in 1980, the Carter Center took the reins and has since led the effort with additional support from partners like WHO, UNICEF, and the Gates Foundation. The number of people infected by the worm has been reduced from 3.5 million in 1986 to 25,217 cases in 2006—an astounding drop of 99 percent. In the three countries where the worm existed outside Africa—India, Pakistan, and Yemen—eradication is complete. The remaining cases are found in a handful of countries in Africa, mainly in Sudan and Ghana.47

Some leading sources of premature death are lifestyle-related, such as smoking. WHO estimates that 5.4 million people died in 2005 of tobacco-related illnesses, more than from any single infectious disease. Today there are some 25 known health threats that are linked to tobacco use, including heart disease, stroke, respiratory illness, many forms of cancer, and male impotence. Cigarette smoke kills more people each year than all other air pollutants combined—more than 5 million versus 3 million.48

Impressive progress is being made in reducing cigarette smoking. After a century-long buildup of the tobacco habit, the world is turning away from cigarettes, led by WHO’s Tobacco Free Initiative. This gained further momentum when the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the first international accord to deal entirely with a health issue, was adopted unanimously in Geneva in May 2003. Among other things, the treaty calls for raising taxes on cigarettes, limiting smoking in public places, and strong health warnings on cigarette packages. In addition to WHO’s initiative, the Bloomberg Global Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, funded by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, is working to reduce smoking in lower-and middle-income countries, including China.49

Ironically, the country where tobacco originated is now leading the world away from it. In the United States, the average number of cigarettes smoked per person has dropped from its peak of 2,814 in 1976 to 1,225 in 2006—a decline of 56 percent. Worldwide, where the downturn lags that of the United States by roughly a dozen years, usage has dropped from the historical high of 1,027 cigarettes smoked per person in 1988 to 859 in 2004, a fall of 16 percent. Media coverage of the health effects of smoking, mandatory health warnings on cigarette packs, and sharp increases in cigarette sales taxes have all contributed to the steady decline.50

Indeed, smoking is on the decline in nearly all the major cigarette-smoking countries, including such strongholds as France, China, and Japan. The number of cigarettes smoked per person has dropped 20 percent in France since peaking in 1991, 5 percent in China since its peak in 1990, and 20 percent in Japan since 1992.51

Following approval of the Framework Convention, a number of countries took strong steps in 2004 to reduce smoking. Ireland imposed a nationwide ban on smoking in workplaces, bars, and restaurants; India banned smoking in public places; Norway and New Zealand banned smoking in bars and restaurants; and Scotland banned smoking in public buildings. Bhutan, a small Himalayan country sandwiched between India and China, has prohibited tobacco sales entirely.52

A number of countries have since adopted a variety of measures designed to limit smoking and exposure to smoke for nonsmokers. In 2005, smoking was banned in public places in Bangladesh, and Italy banned it in all enclosed public spaces, including bars and restaurants. More recently, England has forbidden it in workplaces and enclosed public spaces, and France is phasing in a similar ban by 2008.53

In the United States, which already has stiff restrictions on smoking, the Union Pacific Corporation stopped hiring smokers in seven states as an economy measure to cut health care costs. General Mills imposes a $20-a-month surcharge on health insurance premiums for employees who smoke. Each of these measures helps the market to more accurately reflect the cost of smoking.54

More broadly, a 2001 WHO study analyzing the economics of health care in developing countries concluded that providing the most basic health care services, the sort that could be supplied by a village-level clinic, would yield enormous economic benefits for developing countries and for the world as a whole. The authors estimate that providing basic universal health care in developing countries will require donor grants totaling $27 billion in 2007, scaled up to $38 billion in 2015, or an average of $33 billion per year. In addition to basic services, this $33 billion includes funding for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and for universal childhood vaccinations.55

Curbing the HIV Epidemic

Although progress is being made in curbing the spread of HIV, 4.3 million people were newly infected in 2006. More than 40 million have died from AIDS thus far, two thirds of them in Africa—the epicenter of the disease.56

The key to curbing the AIDS epidemic, which has so disrupted economic and social progress in Africa, is education about prevention. We know how the disease is transmitted; it is not a medical mystery. In Africa, where once there was a stigma associated with even mentioning the disease, governments are beginning to design effective prevention education programs. The first goal is to reduce quickly the number of new infections, dropping it below the number of deaths from the disease, thus shrinking the number of those who are capable of infecting others.

Concentrating on the groups in a society that are most likely to spread the disease is particularly effective. In Africa, infected truck drivers who travel far from home for extended periods often engage in commercial sex, spreading HIV from one country to another. Sex workers are also centrally involved in spreading the disease. In India, for example, educating the country’s 2 million female sex workers, who have an average of two encounters per day, about HIV risks and the life-saving value of using a condom pays huge dividends.57

Another target group is the military. After soldiers become infected, usually from engaging in commercial sex, they return to their home communities and spread the virus further. In Nigeria, where the adult HIV infection rate is 4 percent, former President Olusegun Obasanjo introduced free distribution of condoms to all military personnel. A fourth target group, intravenous drug users who share needles, figures prominently in the spread of the virus in the former Soviet republics.58

At the most fundamental level, dealing with the HIV threat requires roughly 13.1 billion condoms a year in the developing world and Eastern Europe. Including those needed for contraception adds another 4.4 billion. But of the 17.5 billion condoms needed, only 1.8 billion are being distributed, leaving a shortfall of 15.7 billion. At only 3.5¢ each, or $550 million, the cost of saved lives by supplying condoms is minuscule.59

The condom gap is huge, but the costs of filling it are small. In the excellent study Condoms Count: Meeting the Need in the Era of HIV/AIDS, Population Action International notes that “the costs of getting condoms into the hands of users—which involves improving access, logistics and distribution capacity, raising awareness, and promoting use—is many times that of the supplies themselves.” If we assume that these costs are six times the price of the condoms themselves, filling this gap would still cost only $3 billion.60

Sadly, even though condoms are the only technology available to prevent the sexual spread of HIV, the U.S. government is de-emphasizing their use, insisting that abstinence be given top priority. While encouraging abstinence is desirable, an effective campaign to curb the HIV epidemic cannot function without condoms.61

One of the few African countries to successfully lower the HIV infection rate after the epidemic became well established is Uganda. Under the strong personal leadership of President Yoweri Museveni, the share of adults infected dropped substantially during the 1990s and has remained stable since 2000. Senegal, which acted early and decisively to check the spread of the virus and which has an adult infection rate of less than 1 percent, is also a model for other African countries.62

The financial resources and medical personnel currently available to treat people who are already HIV-positive are severely limited compared with the need. For example, of the 4.6 million people who exhibited symptoms of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa in 2006, just over 1 million were receiving the anti-retroviral drug treatment that is widely available in industrial countries. Although the number getting treatment is only one fourth of those in need, it is double the number treated during the preceding year.63

There is a growing body of evidence that the prospect of treatment encourages people to get tested for HIV. It also raises awareness and understanding of the disease and how it is transmitted. And if people know they are infected, they may try to avoid infecting others. To the extent that treatment extends life (the average extension in the United States is about 15 years), it is not only the humanitarian thing to do, it also makes economic sense. Once society has invested in the rearing, education, and on-job training of individuals, the value of extending their working lifetime is high.64

Treating HIV-infected individuals is relatively costly, but ignoring the need for treatment is a strategic mistake simply because treatment strengthens prevention efforts. Africa is paying a heavy cost for its delayed response to the epidemic. It is a window on the future of other countries, such as India and China, if they do not move quickly to contain the virus that is already well established within their borders.65

Reducing Farm Subsidies and Debt

Eradicating poverty involves much more than international aid programs. For many developing countries, the reform of farm subsidies in aid-giving countries and debt relief may be even more important. A successful export-oriented farm sector—taking advantage of low-cost labor and natural endowments of land, water, and climate to boost rural incomes and to earn foreign exchange—often offers a path out of poverty. Sadly, for many developing countries this path is blocked by the self-serving farm subsidies of affluent countries. Overall, industrial-country farm subsidies of $280 billion are roughly 2.5 times the development assistance flows from these governments.66

The size of the agricultural budget of the European Union (EU) is staggering, accounting for over one third of its total annual budget. It also looms large internationally. In 2005 the EU-25 accounted for $134 billion of the $280 billion spent by affluent countries on farm subsidies. The United States spent $43 billion on farm subsidies. These encourage overproduction of farm commodities, which then are sent abroad with another boost from export subsidies. The result is depressed world market prices, particularly for cotton, one of the commodities where developing countries have the most to lose.67

Although the European Union accounts for more than half of the $104 billion in development assistance from all countries, much of the economic gain from this assistance in the past was offset by the EU’s annual dumping of some 6 million tons of sugar on the world market. This is one farm commodity where developing countries have a strong comparative advantage they should be permitted to capitalize on. Fortunately, in 2005 the EU announced that it would reduce its sugar support price to farmers by 40 percent, thus discouraging the excess production that lowered the world market price. The affluent world can no longer afford farm policies that permanently trap millions in poverty by cutting off their main avenue of escape.68

Additional help in raising world sugar prices may come from an unexpected quarter. Rising oil prices appear to be increasing sugar prices as more and more sugarcane-based ethanol refineries are built. In effect, the price of sugar may start to track the price of oil upward, providing an economic boost for those developing-world economies where nearly all the world’s cane sugar is produced.69

Recent developments may also lift world cotton prices. Production subsidies provided to farmers in the United States have historically enabled them to export cotton at low prices. These subsidies to just 25,000 American cotton farmers exceed U.S. financial aid to all of sub-Saharan Africa’s 800 million people. And since the United States is the world’s leading cotton exporter, its subsidies depress prices for all cotton exporters.70

U.S. cotton subsidies have faced a spirited challenge from four cotton-producing countries in Central Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali. In addition, Brazil successfully challenged U.S. cotton subsidies within the framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Using U.S. Department of Agriculture data, Brazil convinced the WTO panel that U.S. cotton subsidies were depressing world prices and harming their cotton producers. In response, the panel ruled in 2004 that the United States had to eliminate the subsidies.71

After the 2004 WTO ruling, the United States removed some export-credit guarantees and payments to domestic mills and exporters to buy U.S.-grown cotton. In response, Brazil argued that the U.S. payments to farmers continued to depress world cotton prices. The WTO again ruled in Brazil’s favor. Despite this ruling, the Farm Bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in the summer of 2007 included cotton subsidies in violation of the WTO rules.72

Along with eliminating harmful agricultural subsidies, debt forgiveness is another essential component of the broader effort to eradicate poverty. For example, with sub-Saharan Africa spending four times as much on debt servicing as it spends on health care, debt forgiveness can help boost living standards in this last major bastion of poverty.73

In July 2005, heads of the G-8 group of industrial countries, meeting in Gleneagles, Scotland, agreed to the cancellation of the multilateral debt that a number of the poorest countries owed to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the African Development Bank. This initiative, immediately affecting 18 of the poorest debt-ridden countries (14 in Africa and 4 in Latin America), offered these countries a new lease on life. Up to another 20 of the poorest countries could benefit from this if they can complete the qualification. A combination of public pressure by nongovernmental groups campaigning for debt relief in recent years and strong leadership from the U.K. government were the keys to this poverty reduction breakthrough.74

The year after the Gleneagles meeting, Oxfam International reported that the International Monetary Fund had eliminated the debts owed by 19 countries, the first major step toward the debt relief goal set at the G-8 meeting. For Zambia, the $6 billion of debt taken off the books enabled President Levy Mwanawasa to announce that basic health care would be now free. In Oxfam’s words, “the privilege of the few became the right of all.” In East Africa, Burundi announced it would cancel school fees, permitting 300,000 children from poor families to enroll in school. In Nigeria, debt relief has been used to set up a poverty action fund, some of which will go to training thousands of new teachers.75

If the international community continues to forgive debt, it will be a strong step toward eradicating poverty. Yet there is still room for progress. The Gleneagles’ commitment eliminates only a minor share of poor-country debt to international lending institutions. In addition to the 19 countries granted relief so far, there are at least 40 more countries with low incomes that desperately need help. The groups that are lobbying for debt relief, such as Oxfam International, believe it is inhumane to force people with incomes of scarcely a dollar per day to use part of that dollar to service debt. They pledge to keep the pressure on until all the debt of these poorest countries is cancelled.76

A Poverty Eradication Budget

Many countries that have experienced rapid population growth for several decades are showing signs of demographic fatigue. Countries struggling with the simultaneous challenge of educating growing numbers of children, creating jobs for swelling ranks of young job seekers, and dealing with the environmental effects of population growth are stretched to the limit. When a major new threat arises—such as the HIV epidemic—governments often cannot cope.

Problems routinely managed in industrial societies are becoming full-scale humanitarian crises in developing ones. The rise in deaths in several African countries marks a tragic new development in world demography. In the absence of a concerted effort by national governments and the international community to accelerate the shift to smaller families, events in many countries could spiral out of control, leading to more death and to spreading political instability and economic decline.

There is an alternative to this bleak prospect, and that is to help countries that want to slow their population growth to do so quickly. This brings with it what economists call the demographic bonus. When countries move quickly to smaller families, growth in the number of young dependents—those who need nurturing and educating—declines relative to the number of working adults. In this situation, productivity surges, savings and investment climb, and economic growth accelerates.77

Japan, which cut its population growth in half between 1951 and 1958, was one of the first countries to benefit from the demographic bonus. South Korea and Taiwan followed, and more recently China, Thailand, and Viet Nam have benefited from earlier sharp reductions in birth rates. This effect lasts for only a few decades, but it is usually enough to launch a country into the modern era. Indeed, except for a few oil-rich countries, no developing country has successfully modernized without slowing population growth.78

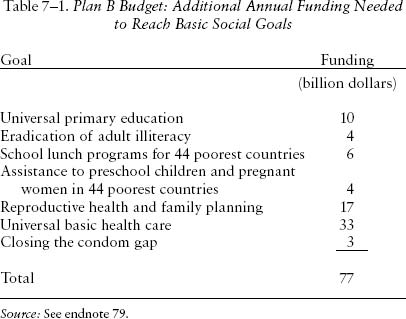

The steps needed to eradicate poverty and accelerate the shift to smaller families are clear. They include filling several funding gaps, including those needed to reach universal primary education; to fight infectious diseases, such as AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria; to provide reproductive health care; and to contain the HIV epidemic. Collectively, the initiatives discussed in this chapter are estimated to cost another $77 billion a year. (See Table 7–1.)79

The heaviest investments in this effort center on education and health, which are the cornerstones of both human capital development and population stabilization. Education includes both universal primary education and a global campaign to eradicate adult illiteracy. Health care includes the basic interventions to control infectious diseases, beginning with childhood vaccinations.80

As Jeffrey Sachs regularly reminds us, for the first time in history we have the technologies and financial resources to eradicate poverty. As noted earlier, the last 15 years have seen some impressive gains. For example, China has not only dramatically reduced the number living in poverty within its borders, but, with its trade and investment initiatives, it is helping poorer countries develop. China is investing substantial sums in Africa—investments often related to helping African countries develop their abundance of mineral and energy resources, something that China needs.81

Helping low-income countries break out of the demographic trap is a highly profitable investment for the world’s affluent nations, a way of reducing the number of failing states. Industrial-country investments in education, health, and school lunches are in a sense a humanitarian response to the plight of the world’s poorest countries. But more fundamentally, they are investments that will shape the world in which our children will live.