3PALESTINE UNDER BRITISH RULE

On December 11, 1917, the eve of the Hanukkah festival, General Sir Edmund Allenby entered Jerusalem, opening a new period in the history of Palestine, Zionism, and the Jewish people. As befitting a modest pilgrim, Allenby dismounted from his horse at the Old City wall and entered the city on foot—the city that had not seen a Christian conqueror since Godfrey of Bouillon in 1099. In this way four centuries of Ottoman rule came to an end.

The war years had left a ruined country whose Jewish community had barely survived. Of the 85,000 Jews living there in 1914, only 56,000 remained to welcome the new conqueror. The Arab population, too, had suffered greatly; some 100,000 had fled, been killed, or died of disease and hunger.

When the war broke out the Ottomans seized the opportunity to rescind the system of capitulations. Overnight the country’s foreign subjects found themselves at the mercy of the Ottoman bureaucracy’s arbitrariness. People lost faith in Turkish currency, which led to the hoarding of food and staples, and a run on the banks. The authorities declared a moratorium on withdrawal of money. The situation deteriorated further in October 1914 when Turkey entered the war on Germany’s side. Tens of thousands of Russian Jews living in Palestine became enemy subjects and were required either to leave the country or assume Ottoman citizenship, which mandated conscription into the army or the payment of a high indemnity. Many opted to leave.

The government now had the opportunity to vigorously suppress the Zionist movement. Jamal Pasha, the Ottoman commander-in-chief in Syria and Palestine, proscribed any expression of Jewish autonomy. The use of Anglo-Palestine Company banknotes, replacing those that had disappeared from the market, was forbidden. All the Hebrew street signs in Tel Aviv were taken down. The moshavot and Tel Aviv were constantly under threat of searches for weapons, and Jewish guards were forbidden. Defense of the Yishuv was left to Turkey’s ally Germany and to the United States, which until 1917 remained neutral. Had it not been for the Germans and Americans, Jamal Pasha would have succeeded in destroying the Yishuv.

The war in the Mediterranean cut the Yishuv off from Europe and hit it hard economically. The citrus growers were unable to export their fruit or the vintners their wine. The Jewish charitable institutions that supported the old Yishuv could not transfer funds to the needy. The Yishuv was threatened by famine and only rescued by the efforts of the American ambassador in Istanbul, Henry Morgenthau, who interceded with the authorities. As a result, American warships were allowed to bring money and vital supplies to the Yishuv. The aid provided to the Yishuv by American Jewry in the war years amounted to a million dollars and saved it from annihilation. No less important than the economic aid was the message conveyed to both the Turks and the Arabs by the vessels of this neutral power: the Jews have powerful allies and should not be mistreated.

Etched in the Yishuv’s collective memory are three dramatic events: the brutal deportation of foreign subjects on January 17, 1914; the expulsion from Tel Aviv and Jaffa in April 1917; and the Nili Affair in September–October 1917. The deportation of the foreign subjects from Palestine was executed without prior warning. A sudden announcement informed all foreign subjects that they must immediately board an Italian ship anchored in Jaffa Port that was about to sail to Alexandria. Pandemonium ensued. The police treated the deportees savagely; families were separated from their children, and cargo and baggage were loaded without their owners. Some dreadful scenes led the German consul to lodge a bitter complaint with his counterpart in Istanbul. Jamal Pasha was reprimanded, while the officer in charge of the deportation was transferred from his post. Mass deportations were stopped but replaced by selective ones. With the clear intention of driving out every last vestige of the Yishuv leadership, the Turks ordered party leaders, heads of local committees, teachers, public intellectuals, and all leaders of Zionist institutions to leave. On the eve of the British conquest of Palestine, the leadership elite formed in the days of the Second Aliya was absent from the country.

The second event was the expulsion from Jaffa. After Allenby’s failed attempt to take Gaza in March 1917, the inhabitants of the southern part of the country were ordered by the Turkish authorities to leave their homes and go into exile. The residents of Gaza were forced to move northward, under harsh conditions, with no aid from the authorities. On Passover eve, fueled by the Turks’ fears of Allenby advancing northward, the residents of Jaffa were also ordered to leave. At the time some 10,000 Jews lived in the city, including approximately 2,000 residents of the handsome new neighborhood to the north, Tel Aviv. Carts from the moshavot and the Galilee were the only means of transport available to the exiles, and they rolled out of Tel Aviv loaded with bedclothes and kitchen utensils atop which sat the families that had managed to organize themselves before leaving. They were the minority. Most left on foot. Tel Aviv became a ghost town, with only a few young people allowed to remain and guard the houses against looters.

The exiles came first to Petach Tikva, then dispersed to all the moshavot in Samaria and the Galilee. In the meantime a typhus epidemic spread through the Turkish forces, then infected the civilian population. The exiles, who often had to find shelter in shacks or woods adjoining the moshavot, were particularly susceptible to disease, and lacking sanitary conditions or medicines, they were decimated by the epidemic.

The third event was the Nili Affair. The most notable group among the young people of the moshavot was “the Gideonites,” organized in the Samaria moshavot by Alexander Aaronsohn from Zichron Yaʿakov. His brother Aaron was an agronomist who gained world renown after identifying wild emmer, the “mother of all wheat.” He ran an agricultural experimental station at Atlit and impressed Jamal Pasha, who put him in charge of eradication during the plague of locusts of 1915. Aaron Aaronsohn therefore was familiar with Jamal Pasha and his tyrannical methods. Shocked by the genocide of the Armenians after their expulsion from Asia Minor, he saw the British as the saviors of the Yishuv. To help them conquer Palestine—and in hopes of obtaining their assistance for Zionism—he organized an espionage network, Nili (a Hebrew acronym for “The Eternal One of Israel will not lie”), whose members were his family, the Gideonites, and other youngsters from the moshavot. Aaronsohn traveled to Egypt, where he made contact with the British authorities, then began to provide them with intelligence on the morale of the Turkish troops, troop movements, fortifications, and plans. In the fall of 1917 the network was uncovered by the Turks. Two of its leaders were captured and executed, and Aaronsohn’s sister Sarah was tortured so viciously that she took her own life. As collective punishment a curfew was imposed on the moshavot, innocent people were arrested and flogged, and some were even taken to Damascus for detention.

The network’s activities aroused controversy within the Yishuv, whose leadership demanded total loyalty to the Turks, insisting that no one give them grounds for destroying the Yishuv. The fate of the Armenians had lit a warning light. Furthermore the notion of a small group setting itself apart and deciding to take independent action that might endanger the entire population was anathema to the leadership, who saw this group as a small minority forcing the hand of the majority. Another objection demonstrates the naivety of the time: espionage was considered ungentlemanly—cheating and deceitful.

Nevertheless it was the members of Nili who brought the story of the expulsion from Jaffa and Tel Aviv to the knowledge of the outside world; and in 1917, with British help, they brought gold coins into Palestine when all other ways of bringing money into the country were blocked. Though the leadership had sharply criticized them, it was not averse to accepting these funds, which were vital for the Yishuv’s continued functioning and for preventing actual starvation. The importance of the Nili Affair lay in its ramifications for the relations among various groups in the Yishuv that were striving for dominance and for the issue of accepting the authority of the majority.

The Jews welcomed the conquering British as liberators, or in the terminology of the time, “redeemers.” Girls born that year were named Geula (Redemption) and boys Yigal (from the same Hebrew root) to mark the beginning of a new era of great expectations. Enthusiasm for the British derived primarily from the awareness that as long as the Turks were in power, there was no hope for Zionism. Second, Britain was a European nation with proper governance, a welcome change after the tyrannical, corrupt rule of the Ottomans. Third, news of the Balfour Declaration had spread throughout Palestine, and hopes for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine reached new heights.

THE BALFOUR DECLARATION

Max Nordau, the most important of Herzl’s partners in the Zionist adventure, remarked on the eve of Turkey’s entry into the war in the fall of 1914 that the Zionist movement had no real achievements, nor had it made any commitments, and that its only hope was the fall of the Ottoman Empire. During the war years the Zionist Organization maintained an office in neutral Copenhagen and scrupulously avoided taking sides in the conflict. The reason for this policy was that the Zionist movement was a worldwide organization, and any identification with one side might harm Zionists on the other. With regard to their personal loyalties, the Jews were ambivalent. They considered France and Britain the countries with the most liberal attitudes toward them, and quite naturally the Jews wanted to side with these nations. But Tsarist Russia, which the Jews hated for its discriminatory policies and persecution of them, was the ally of France and Britain. Thus the Jews’ support for the Entente Powers was only partial. On the other hand, a victory by the Central Powers, led by Germany and including Ottoman Turkey, meant continued Turkish rule in Palestine, with no chance for Zionism to succeed.

From the beginning of the war, however, some individuals acted on their own initiative, in defiance of Zionist Organization discipline, to link the Zionist movement with Britain. Among these the most notable were Vladimir (Zeʾev) Jabotinsky, a Russian-Zionist journalist, writer, and politician, and Chaim Weizmann, a chemist and researcher at the University of Manchester and a leader of the Democratic Faction, a group in opposition to Herzl. Jabotinsky attempted to start a movement in which Russian Jews who had immigrated to England would enlist in the British Army. He hoped that these special units, known as the Jewish Legion, would rouse British interest in Zionism and perhaps encourage a certain commitment to it. Weizmann worked to create a pro-Zionist lobby among the British leadership.

British interest in Palestine was aroused once it became clear that the days of the Ottoman Empire were numbered. Following the failed Turkish attempt to attack British posts along the Suez Canal in 1915, the British realized that the Sinai Peninsula, which they had thought was a natural barrier preventing armies from reaching the canal, was passable. Palestine now became a strategic asset, not only as a stepping-stone to Suez but also as part of the overland route to India through Egypt, Transjordan, Iraq, and the Persian Gulf. India was indeed the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, on which the sun had not yet set. Later, in the 1930s, oil fields were discovered in the Middle East, adding to its importance, but when the fate of the region was decided after World War One, the foremost considerations revolved around the region’s imperial routes.

Starting in spring 1915 Palestine was a topic discussed in the British cabinet and between Britain and France. In a secret agreement signed in May 1916 between Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, which had been under negotiation since the fall of 1915, they agreed upon the division of the Ottoman Empire. Iraq and the overland route in southern Palestine and Transjordan came under the British sphere of influence, while the French were given Syria and Lebanon. Western Palestine, to the south of the Sea of Galilee and north of Gaza, was to be under international rule.

At the same time, the high commissioner in Egypt, Sir Arthur Henry McMahon, acting on his government’s behalf, promised Sharif of Mecca Hussein bin Ali that in return for an Arab revolt against the Ottomans, with the sharif ’s armies taking Syria, Britain would support Arab independence from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean and as far as the Taurus Mountains, except for western Syria and Lebanon. The document did not mention Palestine specifically, but McMahon claimed that it was made clear to the sharif that this area was not included in the Arab areas. It is not known whether the ambiguity of McMahon’s letter was intentional or not. In any event it was the source of the Arab belief that Palestine had been promised to the different parties on several occasions. The contradictions between the McMahon letter and the Sykes-Picot Agreement are difficult to resolve. According to researcher Isaiah Friedman the intention in the McMahon letter was to give the Arabs not complete independence but rather freedom from the Ottoman yoke, together with European protection. In any event it was clear to the Great Powers that Palestine would have a fate unlike that of the other regions and would be governed internationally.

The story of the Balfour Declaration combines idealism and imperialism, international intrigue, and erroneous assessments of power and weakness. For the first two years of the war, Weizmann conducted a pro-Zionist campaign in the British corridors of power, but he made little progress until December 1916, when David Lloyd George became prime minister. Lloyd George, a Protestant brought up on the Bible, harbored deep sentiments regarding the connection between the Jews and the Holy Land. He was greatly influenced by the romantic idea of the Jews returning to their ancient homeland that was prevalent in nineteenth-century Britain and fired up by the Zionist idea. He also believed that the Zionists and Britain had common interests, which he saw as a lever for freeing Britain from its commitment to the French that Palestine would be international; he wanted to keep it under British control.

Lloyd George’s foreign secretary was Arthur Balfour, an urbane and imaginative man who both admired and feared Jewish genius. The combination of Lloyd George and Balfour in the British cabinet at the critical moment in 1917 created the declaration bearing Balfour’s name. Although in the end the British interest in controlling the overland route to India and not allowing France a toehold in Palestine was decisive, the rationale for the declaration changed periodically during the negotiations that led to its publication. Each succeeding rationale, however, was based on an overestimation of Jewish power in the world; here the essentially antisemitic image of the omnipotent Jew played into the Zionists’ hands. In the United States, which until spring 1917 was neutral, most American Jews, like the Irish and German minorities, supported the Central Powers. They had hardly any influence on U.S. policy and indeed, before the Balfour Declaration was even published, America had entered the war on the side of the Entente Powers.

In Russia a liberal revolution took place in the spring of 1917, and the Zionist movement enjoyed a surge forward. The British believed that the Zionists were the decisive element among Jews, who they thought controlled the Russian revolutionaries. The British hope was that Jewish support would moderate these revolutionaries, who were advocating Russian withdrawal from the war. The British also feared a German pro-Zionist declaration that would preempt the Balfour Declaration, thus leading Jews to support the Central Powers. But the Germans’ hands were tied by their Turkish allies. However, the prolonged discussions on the declaration, the scrupulous consideration of its every word, show that it was not intended as part of a propaganda war, whose effect would dissipate the moment it was no longer needed, but as a political declaration of cardinal importance.

The declaration, which was conveyed on November 2, 1917, from the British foreign secretary to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, states:

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other countries.

The declaration assured the Jews of an opportunity to establish a “national home” in Palestine. The British were to facilitate this enterprise, but it had to be implemented by the Jews themselves. Although the declaration did not promise a Jewish state, in private discussions the British statesmen explained that the ultimate intention was to create a state when the Jews should constitute the majority of the country’s population. There was no mention of the borders of this national home, but in time the words “in Palestine” would be interpreted as implying that not all of Palestine had been promised to the Jews as a national home. The two qualifications, regarding non-Jewish communities in Palestine and Jews not interested in Zionism, were added in the final stages of the declaration’s formulation and refer not to national rights but only to civil and religious ones. It is striking that the Arabs are mentioned only as “non-Jewish communities,” not by name.

Like the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Balfour Declaration belongs to an era in which a handful of statesmen in smoke-filled rooms decided the fates of peoples and states and how to divide up declining empires, with no participation by the media or the masses. From Zionism’s standpoint this was a unique opportunity. In these final days of globe-spanning imperialism, these few statesmen not only dared to act in accordance with political common sense but were also driven by a spiritual vision. To Balfour, Lloyd George, Mark Sykes, and others, the idea of the Jews returning to their country seemed a lofty enterprise worthy of their support, even though it ran counter to the Powers’ declarations on the right of nations to self-determination that had been one of the objectives of the war. The opposition of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine seemed to them of secondary importance when compared with compensating the Jews for thousands of years of persecution and debasement. In his blunt style Balfour defined the situation in the following words:

The Four Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, and future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion that is right.1

Although the motivation of these British statesmen to support the Jewish national home was sincere, at the same time Zionism provided a convenient pretext for getting control of Palestine. The British were able to present their desire to rule Palestine as arising from the needs of the Jewish national movement, not their own imperialistic ambitions. At the very same time, the British were encouraging the Arab national movement through T. E. Lawrence, who fomented the “Revolt of the Desert”—more a stirring myth than a campaign with any military value. Mark Sykes believed that there was no contradiction between Jewish and Arab nationalism and strove for cooperation between them. As long as Faisal, the son of Sharif Hussein and the future king of the great Arab kingdom, led the Arab national movement, its hostility toward the Zionist movement was not pronounced. But from the moment in 1920 that Faisal was ousted from Syria by the French, who were not prepared to relinquish their part of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the rising nationalist emotions of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine focused on their opposition to Zionism.

The British conquest of Palestine in 1918 did not take place under the banner of the Balfour Declaration. The declaration was not officially published in Palestine, although its content was known to both Jews and Arabs. From the Jewish viewpoint it was the charter that Herzl had so fervently sought, while the Arabs saw it as undermining their centuries-old superiority in Palestine. Their concern over the appearance of another claimant to ownership of the country was genuine, even though some made political capital from it. The Palestinian triangle of British, Arabs, and Jews was formed at that moment in December 1917 when Allenby dismounted outside Jerusalem. For the next thirty years this trilateral relationship lay at the heart of the Palestine dilemma.

The story of the thirty-year-long British rule in Palestine is a tale of Britain’s slow withdrawal from its pro-Zionist commitments, the Zionist leadership’s efforts to exert pressure on the British to meet those commitments, and Arab pressure in the opposite direction, with each party accusing Britain of betrayal, reneging on its promises, and unfairness. In the end the British left Palestine, slamming the door behind them and leaving a country embroiled in a civil war—or a war between national communities—that rapidly evolved into a war between countries. They also left behind a Jewish community capable of withstanding the horrors of that war and that established the State of Israel.

Historian Elizabeth Monroe has described the Balfour Declaration as “one of the greatest mistakes in our [British] imperial history,” which greatly damaged Britain. This assertion assumes that everything that took place in the Middle East was a consequence of the Balfour Declaration and gives the story a moralistic element: the British did not keep their promises to the Arabs and therefore were doomed to lose their standing in the Middle East. The Zionists also moralized the story: the British reneged on their undertakings to the Jews in order to placate the Arabs, but the Arabs did not remain loyal to them, and they lost the support of the Jews, thus losing their rule over the Middle East. Both these narratives ignore the rise of nationalism and the dismantling of the great empires, which happened regardless of the appearance of Zionism and whether or not the British remained loyal to the Jews. It is difficult to assume that Britain could have maintained its standing in the Middle East even if there were no Zionist movement.

The British rule in Palestine can be roughly divided by decade: 1918–1929; 1929–1939; and 1939–1948. This division encompasses certain major events affecting relations within the Palestine triangle and highlights the way political factors shaped reality in Palestine. The first decade, which came after a period of instability and unrest, was characterized by relative quiet, the shaping of Mandatory rule, and the weakness of both the Arab national and Zionist movements. This stability ended with the 1929 riots, a violent Arab outburst that led to a series of British decisions intended to curb the development of the Jewish national home. The Zionists succeeded in having these restrictions annulled in 1931, and a period of economic and population growth ensued until 1936. That year saw the outbreak of the Arab Revolt, a popular uprising against the Jews and the British that continued intermittently until 1939, when it was brutally quelled by the British. In May 1939 the colonial secretary announced a new policy intended to freeze the development of the Jewish national home. This date marks the end of the alliance between the Zionist movement and Britain. The third decade began with World War Two and ended with the termination of the British Mandate for Palestine following the United Nations General Assembly resolution of November 29, 1947.

1918–1929

Any change in the status of Palestine was linked to the delicate relations within the Palestine triangle. The decision to end the military government—which had been extended due to Turkey’s rejection of the Treaty of Sèvres—and enact civil rule, even before the British Mandate for Palestine was officially ratified, was made because on Passover in 1920 (April 4) rioting broke out, mainly in Jerusalem. Arabs attacked Jews, wounding, killing, and damaging property. The military authorities, who were not devout supporters of the Balfour Declaration and were inclined toward the Arabs’ side, strove to maintain the status quo, as would be expected of a temporary military government. This meant suppressing the aspirations of the Jews, who wanted to implement changes following the Balfour Declaration regarding immigration, land purchase, and making Hebrew the offi-cial language. Thus there was a clear contradiction between the Balfour Declaration and the policy actually enforced in Palestine.

The San Remo Convention of the victorious powers decided on April 18, 1920, shortly after the rioting, to grant Britain the Mandate for Palestine and give it responsibility for implementing the Balfour Declaration. The Balfour Declaration thus ceased to be a unilateral British declaration and became the policy of the Entente Powers, with international legal status. Because of the pro-Arab leanings of the military government, it was decided at San Remo to transfer power from the military to a civil government. Herbert Samuel, a keen British Zionist and former minister—a man of great talent and administrative experience, and also a man of action—was appointed Palestine’s first high commissioner. This was a clear pro-Zionist statement by the British government, still headed by Lloyd George.

The next act in the Palestine drama took place about a year later: Herbert Samuel arrived in Palestine, to be greeted with great warmth by the Jews and undisguised suspicion by the Arabs. The country appeared quiet and it seemed that reconstruction and building could begin, but in May 1921 there was a resurgence of violence that started in Jaffa and spread to the moshavot. The authorities had difficulty quelling the riots, which went on for several days, resulting in the deaths of dozens of Jews. The British response this time inaugurated what became a recurring pattern. The high commissioner delivered a speech placating the Arabs in which he announced a temporary halt to immigration to Palestine. To conciliate them even further he appointed Haj Amin al-Husseini as Mufti of Jerusalem. Al-Husseini, a scion of a notable Jerusalem family and a radical nationalist, had been tried for involvement in the 1920 Passover riots.

In the meantime the draft League of Nations instrument for the British Mandate for Palestine was being formulated. The mandatory system was a consequence of international anti-imperialist sentiment in the wake of World War One and the Bolshevik Revolution. Instead of annexing countries France and Britain took responsibility for administering certain countries for a limited period while preparing them for independence. France was granted the Mandate for Syria, and Britain the Mandate for Iraq and Palestine, which included Transjordan. The draft instrument of the British Mandate for Palestine was pro-Zionist: it included the Balfour Declaration and recognized the historical connection between the Jewish people and Palestine. Article 2 referred to “placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home.” Article 4 spoke of “an appropriate Jewish agency” that would “take part in the development of the country . . . in consultation with His Britannic Majesty’s Government.” Article 6 referred to “close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands.” The Arabs were not mentioned by name in the instrument, which was directed mainly toward the development of a Jewish national home.

Now, trying to pacify the Arabs in the wake of the riots, in June 1922 the Colonial Office under Winston Churchill published a White Paper that announced a new British policy in the guise of an interpretation of the Mandate instrument. It assured the Arabs “that it [the Mandate] does not contain or imply anything which need cause alarm to the Arab population of Palestine.” The Zionist Organization had status only on matters pertaining to the life of the Jews, but the White Paper did state that the Jews were in Palestine “as of right and not on sufferance.” On the other hand, the intention was not that Palestine become the national home, but that a national home would be established in Palestine. The White Paper also stated that “immigration cannot be so great in volume as to exceed whatever may be the economic capacity of the country at the time to absorb new arrivals. It is essential to ensure that the immigrants should not be a burden upon the people of Palestine as a whole.” The paper further raised the idea of a legislative council that would give expression to the inhabitants’ wishes, and although this body would not be democratically elected, the mere mention of it was an expression of the right of the Arab majority to political representation. From a policy favoring a Jewish national home, the pendulum now began to swing toward granting rights and representation to the Arab population.

The men behind the White Paper, Samuel and Churchill, were loyal supporters of Zionism. The new policy was designed to allay Arab fears and create the cooperation, or at least the calm, that was necessary for immigration, economic development, and advancing Zionist settlement. But not all Zionists accepted this approach, so that from then on there were two opposing points of view on British policy. The first considered the 1922 White Paper an appalling surrender to Arab aggression that rewarded the aggressor and a demonstration of weakness that would inspire further aggression. This group believed that if Samuel had adopted an iron-fist policy and made it clear that Britain was determined to implement the national home policy, the Arabs would have bowed to the inevitable.

The other group contended that it was impossible to subdue an awakening national movement by force and that Britain, exhausted by the war, could not be expected to adopt a policy requiring substantial spending on security as well as harsh suppression of popular resistance. British public opinion, which was opposed to imperialist commitments, would have turned its back on Zionism and the Jewish national home. To gain the time required to build up a Jewish critical mass in Palestine before Britain decided that the Mandate had run its course, the Jews needed to calm the troubled waters.

In 1921 it was clear that the international moment of opportunity that had led to the great achievements of the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate instrument had passed, and the tide was turning in favor of the Arabs. The Arab Executive Committee sent a delegation to London that received support from the British press and politicians, and public opinion began to display an awareness of the position of the Arabs, who were presented as victims of the Balfour Declaration. Thus Samuel’s conciliatory and fair policy toward the Arabs—which large segments of the Yishuv perceived as nothing other than betrayal—was in fact the only one possible, given the situation. During his five years as high commissioner, Samuel stabilized the situation, put in place the mechanisms of the Mandatory government, and brought about economic growth and relative peace. The fact that the Jews needed calm in order to build the country, while the Arabs benefited from rioting—a dynamic Weizmann had understood before any other Zionist statesman—from then on informed Zionist policy. The opposition to the Zionist Executive (the entity in charge of executing Zionist policy in general) continued to support the demand that Britain employ an iron fist, a demand the British had no inclination to accept.

The decade following the 1921 riots saw a continuation of relative peace. During these years the Palestinian Arab national movement underwent splits and disagreements and lost an opportunity to gain influence when they rejected Samuel’s proposals to establish a legislative council. None of the draft proposals he suggested satisfied them, since participation in such a body, established under the Mandate, would constitute recognition both of the Jews’ rights in Palestine and the legitimacy of the Jewish national home. The Arabs’ total refusal to cooperate with the Mandatory government regarding state policy was understandable (they did cooperate in areas such as health, administration, and education), but in rejecting a legislative council they relinquished an important public platform, thus handing the Jews an advantage. As for the Zionists, their rhetoric—especially their internal rhetoric—remained belligerent, functioning as a safety valve for blowing off steam, but in everyday life and on the political level the Jews cooperated with the pacifying policy of Samuel and his successor, General Herbert Plumer.

1929–1939

The second decade of British rule opened with a storm that lasted two years. It began with a dispute over the Jews’ claim to the Western (Wailing) Wall. Researchers believe that the mufti tried to enhance his status in the Muslim world by fomenting concern that the Jews intended to take over the Temple Mount; in Muslim tradition, the Western Wall area is the place from which the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven on his legendary steed. As early as the nineteenth century, the Jews had made attempts to purchase land around the Wall, which the Arabs interpreted as a desire to take over the holy site. Sites that are holy for several religions are always powder kegs, and a single match can set off an explosion. In this case the match had two components. The first was provocative conduct on the part of British policemen who removed the screen separating men and women during Yom Kippur prayers in September 1928. This action again aroused Arab fears that Jews intended to take control of the site, fears that were enhanced by inflammatory rhetoric on the part of preachers and the press. Arabs threw garbage into the Western Wall alley and directed donkeys through it, disturbing Jews. Muslim calls to prayer were made at high volume. The second component was the Jewish reaction, which involved young hotheads holding nationalist demonstrations at the Wall, proclaiming Jewish rights.

On August 23, 1929, Arab violence erupted in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and throughout the country, and continued for a week. It included particularly brutal acts against two helpless, non-Zionist ultra-Orthodox communities in Hebron and Safed. During Plumer’s term of office as high commissioner, the security forces in Palestine had been reduced to three hundred British policemen, who were unable to control this mass violence. Reinforcements from Egypt and Malta arrived only after the rioting had spread throughout the country. Overall, 133 Jews were killed, settlements were destroyed, and property was looted.

The Jews, whose warnings prior to the rioting had been ignored by the authorities, accused the Mandatory government of losing control and being unconcerned with the inhabitants’ safety. In response the administration claimed that though it was the Arabs who had rioted, the real fault lay with the Jews’ national home policy, which the Arabs feared would lead to their being dispossessed. Sir John Chancellor, who had replaced Plumer as high commissioner, had no sympathy for the Zionist cause. A typical colonial official, he viewed his role as looking after the local population. To him the extraordinary circumstance of the Mandate being designed to change the status quo in Palestine for the benefit of a new element, the Jews, seemed unjust and inappropriate. He was determined to annul the preferential status granted the Jews as a people by the Mandate instrument and to focus Britain’s policy on looking after the interests of the Arabs and the local Jews.

Chancellor had no regard for the Jewish people as a whole—the subject of the Mandate instrument policy—but because the instrument had international validity affirmed by the League of Nations, its terms could not be amended. Therefore he focused on details of implementation, especially issues of settlement and immigration. Since further land purchases by Jews would lead to dispossession of Arabs, he decided, the sale of land should be prevented and Jewish immigration restricted by strictly observing the condition regarding economic capacity.

The Shaw Commission, appointed by the British government to examine the causes of the riots, adopted the high commissioner’s line clearing the administration of culpability. It demanded an investigation of immigration and land issues, as well as progress in creating the legislative council. To rectify the imbalance between Arabs and Jews in the Mandate instrument, the British government now stated that the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate instrument contained a dual commitment: to the Jewish people and to the Arab inhabitants of Palestine. Sir John Hope-Simpson was dispatched to Palestine to study the issues of land, immigration, and development policy, and his conclusions were consistent with the new line. He advised restricting land purchases by Jews and enforcing the principle of economic capacity—not, however, on the basis of the capacity of the Jewish economy created with Jewish capital, but on the basis of the entire country’s capacity. This meant that Arab unemployment would be grounds for halting Jewish immigration.

In October 1930 Colonial Secretary Lord Passfield published a White Paper based on the principle of the “dual commitment,” which negated the distinction between “the Jewish people” and “non-Jewish communities” in Palestine. He accepted Hope-Simpson’s definition of economic capacity and his recommendations on restricting land purchase by Jews. The Arabs claimed that one reason for the rioting was the establishment of the Jewish Agency. Designed to enable non-Zionist Jews to take part in building the country, the Agency heightened the Arabs’ fears of dispossession. Thus Passfield made a point of saying that the Agency had no political status; in accordance with the Mandate instrument, its role was limited to participating in the country’s development. At the same time, he announced the formation of a representative legislative council that would, of course, give expression to the Arab majority.

The Passfield White Paper sparked an international political storm. Weizmann resigned as president of the Zionist Organization in protest. Leading British statesmen and jurists claimed that the White Paper contravened the Mandate instrument and demanded its annulment. Demonstrations were held against it throughout the Jewish world. Fearing harsh criticism from the League of Nations Permanent Mandates Commission, which oversaw implementation of the Mandate, the British government opened negotiations with the Zionist leadership and subsequently published a letter from Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. The MacDonald Letter, which was accorded the same status as a white paper, stated that the undertaking in the Mandate was not confined solely to the Jewish population of Palestine, but to the entire Jewish people, and that the obligation of encouraging Jewish settlement in and immigration to Palestine still stood, assuming that this could be accomplished without harming either the rights or situation of the non-Jewish inhabitants. To the Jews the letter appeared to arrest the erosion of the promises the British had made them and to offer the possibility of continued immigration and settlement—a critical achievement in this decade. For the Arabs, however, the MacDonald Letter, coming as it did after the White Paper, was a “Black Letter.”

The second decade thus began with a demonstration of how fragile the British undertaking to the Jewish people was, making the time element critical in realizing the Zionist vision. Overall the 1920s had been years of international stability, with Britain’s position as the leading imperialist power still standing firm. But in 1929 the New York Stock Exchange crashed, triggering a deep global economic crisis that sent political shock waves throughout Europe. Proto-fascist regimes came to power in Eastern and Central Europe, while Germany witnessed the meteoric rise of the Nazi party, and in 1933, the invitation to Adolf Hitler to serve as chancellor. If in the 1920s the Zionist enterprise seemed to consist of slowly developing a society and culture in the spirit of Ahad Haʿam, in the 1930s its mission became rescue of the persecuted Jews of Poland, Romania, and Germany. In the wake of the economic crisis, all countries applied more stringent immigration laws, and Palestine became the main refuge for Jewish migrants. Evolutionary development no longer met the needs of the Jewish people.

In 1931 the narrow-minded John Chancellor—also tainted with antisemitism—was replaced as high commissioner by Sir Arthur Wauchope, an open-minded man, empathetic toward the Jews and very fair-minded toward the Arabs. Starting in 1932 immigration to Palestine grew, and within a few years the Yishuv, which in 1929 numbered some 170,000, increased to 400,000. Mass immigration changed the face of the country. In this period the Jews passed the point of no return: a Jewish critical mass formed in Palestine that was strong enough to prevent the Arabs from establishing an exclusively Arab state, or so the Zionists thought.

The Arabs were fully aware of this change taking place before their eyes. A country that had been Arab in character was suddenly taking on a new, European aspect. Like the Jews, the Arabs had been experiencing economic growth, but this was scant compensation for the feeling that they were gradually losing control of the country, which only a few years earlier had been essentially theirs. For the first time, radical political forces appeared in the Arab street. These forces were outside the traditional clan framework, in which power was shared between the supporters of the al-Husseini clan, who were fanatically opposed to the Jewish national home while emphasizing the element of Islam, and the relatively moderate Nashashibis, who were prepared to cooperate—to a certain extent—with the Mandatory government.

The Istiklal party, which appeared in the early 1930s, was a political force built not on the old privileged families, but on a modern platform that demanded independence for Palestine as it enlisted educated urban Arab youth into its ranks. The Arabs concluded that the heart of their problem was not the Jews, with whom they thought they could deal by themselves, but the British. In 1933 violent Arab demonstrations demanding self-government were aimed at the authorities, not the Jews. Wauchope had no hesitation in suppressing them by force, but at the same time he initiated a move designed to establish a legislative council in Palestine.

Concealed behind this legislative council idea was a recognition of the right of the Arab majority to majority representation in the government. When the council idea was first mooted by Herbert Samuel in the 1922 White Paper, the Jews had been too weak to oppose it. But now they were compelled to deal with the question of what kind of governmental structure they would propose for Palestine. Until this moment, the conventional wisdom among the majority of Zionists in Palestine was that the British Mandate had created the conditions for building a Jewish majority through immigration and settlement, and that when that majority was achieved a Jewish state would be established. This line of thinking ignored growing Arab nationalism and the Arabs’ emergence as another claimant to rights over the country.

The conventional wisdom was now being contested at both ends of the Zionist political spectrum: on the one hand by the Revisionist movement, led by Vladimir Jabotinsky, and on the other by Brit Shalom (peace alliance). Jabotinsky was convinced that a clash between Jewish and Arab nationalism was inevitable and that Zionism could not be realized without an active British policy establishing a “colonization regime” in Palestine that would grant state lands to the Jews, enable mass immigration and large-scale settlement, and stop any Arab resistance by force. Brit Shalom, for its part, advocated reaching agreement with the Arab national movement at any price. Its watchword was binationalism, which neutralized the issue of majority versus minority by agreeing that in Palestine there were two peoples entitled to an equal share in the country, each of which would have an autonomous cultural life (an idea known as “cultural Zionism” as it related to the Jews). According to this plan, the British would remain in Palestine for an extended period as mediator between the two peoples. Brit Shalom had accepted the slogan “not a majority but many” since the 1920s, but it did not satisfy the Arabs, and Brit Shalom was now prepared to consider capping Jewish immigration, if only as a way to reach agreement with the Arabs. This position was driven by both moral principles and the conviction that time was not on the Zionists’ side, which made an immediate agreement with the Arabs preferable to any delay.

Jabotinsky’s idea of a “colonization regime” was not an option, since the British had already demonstrated that they were not prepared to pull the Jews’ chestnuts out of the fire, and Brit Shalom’s ideas were unacceptable to Jews and Arabs alike. In the wake of the riots, however, the prevailing evolutionary concept was called into question. In the race between emerging Arab nationalism and realization of Zionism, it was clear that Zionism was losing. Arab nationalism was developing far more rapidly than the rate of Jewish immigration to Palestine. These facts forced the Jews to consider the governance options open to them long before they had expected these options to mature.

In the early 1930s there were numerous discussions about what governmental framework to introduce in Palestine. The Zionists began these discussions among themselves in response to the Mandatory government’s placing the legislative council on the agenda. There were some attempts to talk to the Arabs, but they were fruitless, for the Arabs refused to recognize any Jewish right whatsoever to the country. They were prepared to allow Jews who had come to Palestine before the Balfour Declaration to remain, but not to recognize them as a collective with a historical connection to the country.

On the other hand, the Zionists were for the first time prepared to recognize the Arabs’ national rights. Even though the Jews were still a minority, this decision was not easy. From the first moment of this modern return to Zion, the new immigrants had felt that they were the masters of Eretz Yisrael. Their awareness that the development of the Yishuv was too slow enabled them psychologically to relinquish the exclusive right of ownership. But they could not accept that the Arabs held exclusive rights either, and certainly not the right to prevent Jews from settling and developing the country.

The evolutionary strategy relied on deferring any decision on the fate of Palestine until the national home had been strengthened, and in the meantime hoping that the British would continue to faithfully uphold their undertakings in accordance with the Mandate instrument. In the summer of 1932 Chaim Arlosoroff, the head of the Jewish Agency’s Political Department, analyzed the situation and concluded that this fatalistic approach was inappropriate for the Zionist movement. It might perhaps have been suitable if the time available to the Zionist movement had not been limited. But Arlosoroff estimated that the mandate system would end within a few years. He predicted that in the near future a world war would break out, accompanied either by an Arab-British alliance or an Arab revolt, and the entire mandate system would be annulled.

The other options available were division of sovereignty over Palestine between Jews and Arabs—that is, different versions of the binational idea—or partition of the territory. Arlosoroff did not approve of any of these alternatives, not even partition or cantonization, which both Zionist and British circles had begun to consider. Although he noted that partition embodied the two basic elements of Zionism—territory and self-government—Arlosoroff did not support it because the country was so small and because the Jews would not constitute a majority even in the areas designated for them.

Arlosoroff wrote to Weizmann expressing his frustration at the limited possibilities available to the Zionist movement under the British administration, but by then the question of the legislative council was already less urgent, since the pressure from the British regarding the council had eased. A year later, in 1933, mass immigration began, and the national home’s growth rate increased dramatically. The pressure of Jewish adversity changed the reality of Palestine and for a few fateful years removed from the agenda the various ideas for resolving the issue of two nations claiming ownership of the same small country.

For the Middle East in general and Palestine in particular, 1935 was a very eventful year. That year 62,000 Jews immigrated to the country, the largest number in a single year during the Mandate period. Italy invaded and conquered Abyssinia, introducing an element of tension into the Middle East that manifested itself in financial panic and the end of economic prosperity in Palestine. That same year a Muslim terrorist group attacked Jews in northern Palestine. In a battle between that group and the British, the group’s leader, Azaddin al-Qassam, was killed and became the symbol of Palestinian resistance. Finally, in that year Arthur Wauchope formulated his proposal for a legislative council, which was debated in the British parliament and rejected. Once more the Arabs of Palestine felt frustrated at not being given even a crumb of self-government. During the 1930s the other countries of the region underwent decolonization processes. In Iraq the Mandate was replaced by self-government, and in Egypt the terms of the British protectorate were amended in Egypt’s favor. The French Mandate for Syria was also changed to a more liberal system of government following a prolonged strike in that country. Of all the Class A mandate countries, only Palestine remained under a regime that did not grant representation to the majority of the population.

April 1936 saw the outbreak of the Arab Revolt. Like its predecessors it began with a wave of random violence against Jews, but within a few days the Arab Higher Committee took command and made political demands: cessation of immigration and land sales, and representational governance that would place power in the hands of the Arab majority. The committee backed these demands with a countrywide general strike, which demonstrated that the Palestinian national movement had matured and was able to mobilize the masses. The strike lasted about six months, severely damaging the Arab economy. Arab workers did not go out to work, the sale of produce to the Jewish market ceased, and the export of Arab citrus fruit fell. However, if the Arabs thought that an economic boycott would force the Yishuv into submission, it became clear that they were mistaken, for the Yishuv showed that when necessary it could become self-supporting. The Jaffa port was replaced by the jetty at Tel Aviv for exporting citrus fruit and taking in immigrants, who continued to arrive.

Arab gangs sowed terror throughout the country, but the high commissioner avoided using military force to suppress them. In the meantime efforts were made to persuade the Arabs to end the strike so that the Royal Commission could come to Palestine and examine the reasons behind the rioting. Instead the Arabs demanded an end to immigration and assurances of independence, demands the British rejected. In October 1936 the Arab states gave the Arab Higher Committee a way out of the corner it had painted itself into with the strike and accompanying terrorism. They called upon the Palestinians to end the strike while expressing their faith in Britain’s good intentions, and gave assurances of their continued support of the Palestinian Arabs. This intervention transformed a local problem into a regional one.

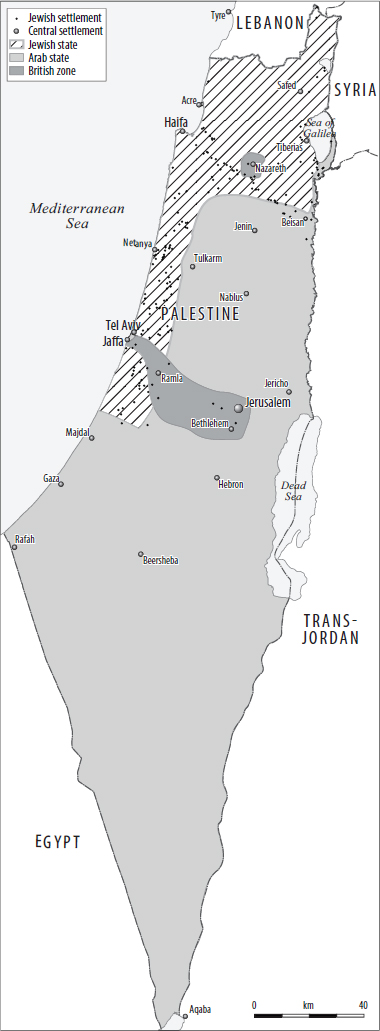

The Royal Commission, better known as the Peel Commission after its chairman, was a high-ranking body that was granted broad authority to examine the entire issue of Palestine and propose a long-term solution. The commission arrived in Palestine in November 1936 and heard testimony from government officials and from Jewish and Arab representatives. Its report was the most thorough, comprehensive, and intelligent document ever written on Palestine during the British Mandate, and its conclusion was radical: the Mandate is unworkable since the undertakings given to the Jews and the Arabs are contradictory. The hope guiding the Mandate administration, which Wauchope expressed in his policies, was that in time a local citizenry would be created, common to Jews and Arabs both, who would live together in one country. Wauchope intended that the Jews would constitute 40 percent of the population, but because of their economic and cultural advantages this would amount to a balance between them and the Arabs. The Peel Commission found that this idea had no basis in reality, since the two national groups in the country not only had nothing at all in common but were embroiled in a bitter conflict over the right of ownership. The commission concluded that the way to satisfy the parties’ desires—at least partially—was to partition the country and establish two independent states, Jewish and Arab. It proposed a partition plan that gave the Jews the coastal plain from Qastina to Rosh Hanikra, the Galilee, and the Jezreel and Jordan Valleys. Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and their environs, and a corridor to Jaffa, would remain under Mandate jurisdiction, while the Arab state would have the remaining territory. The commission also proposed population exchanges between the two states as modeled by those implemented between Turkey and Greece during the 1920s (see map 2). Finally the commission assumed that the Arab state would become part of a federation with Transjordan.

The partition proposal led to bitter dispute among the Jews. Supporters saw it as the seed of an independent Jewish state, while for opponents it meant giving up the vision of the historical Land of Israel, especially since Transjordan had already been sliced off for King Abdullah’s kingdom. The myth of the ancient Land of Israel, of Hebron and Jerusalem and Beth-El, now stood in opposition to the partitioned state. Another group of opponents based their objections not on myth or history but on the rational argument that the partitioned Jewish state would be unable to sustain itself and to absorb and be a refuge for masses of Jews.

Yet at the same time, the proposal presented the first glimmerings of possible Jewish sovereignty. At the Twentieth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1937, there occurred a moment of truth recalling the one during the 1904 debate on Uganda, as political realism clashed with the tradition of generations and the power of myth. In the end, after disputes that threatened to tear the Zionist movement apart, a large majority joined ranks around a resolution allowing the Zionist Executive to enter into negotiations based on the partition plan. However, it had to bring any proposal that was formulated back to the congress for ratification.

The Arabs, by contrast, united swiftly in total opposition to the partition plan and on a demand for independence for Palestine, and the Arab states supported them. In fall 1937 Arab terrorism in Palestine resumed. The authorities imposed martial law and the army took harsh action against the rebels but had difficulty quelling the rebellion, which continued until summer 1939. In the face of Arab opposition, the British government slowly began distancing itself from its own partition plan.

British policy was now guided by the need to ensure peace and quiet in the Middle East. Appeasing the Arabs was part of Britain’s preparations for the approaching conflict in Europe. Starting in fall 1937 winds hostile to the Zionists began to blow in British corridors of power. An anti-Zionist British move was clearly imminent, in the form of reneging on the undertakings in the Mandate instrument and the Balfour Declaration. During the period of tension attending the Munich Pact, which deferred the threat of world war by a year, the Zionists believed they were about to become the next victims of Britain’s appeasement policy.

At the end of 1938 and the beginning of 1939, the British were still ostensibly making efforts to reach a solution acceptable to both Jews and Arabs. However, there was no chance of success, as was clearly demonstrated at the St. James Palace Round Table Conference. When the Arabs refused to sit at the same table with the Jews, the British caved in and arranged separate tables. The British had invited delegates from the Arab states to take part in the conference, hinting that they were willing to make concessions to the Arabs. The agenda included the three Arab demands: independence, an end to immigration, and no more land sales to Jews. After some deliberation the British government decided to accept the Arab position on the majority of the agenda items and issued a document known as the 1939 White Paper, stating that immigration would be limited to 75,000 over a period of five years and that any further immigration would be conditional upon Arab consent. Palestine would become an independent state—that is, a state with an Arab majority—after a ten-year transitional period. Land sales in most regions of the country were restricted.

Of these three restrictions the one most scrupulously enforced was that on immigration. At the most tragic moment in Jewish history, the gates of Palestine were barred to immigrants. The Jewish Agency’s proposals to bring Jewish children from Germany to Palestine or Britain were cynically turned down by the Mandatory authorities. Refugees who reached Palestine after the outbreak of the war were not allowed to stay but were sent to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. If there was one thing that made the Jews of Palestine hate Britain and feel so hostile toward the Mandatory government, it was this attitude toward Jewish refugees during World War Two. The Jews of Palestine placed responsibility for closing the country to war refugees squarely on the government’s shoulders. Once news of the Holocaust arrived, the Jews considered the British to be passive accomplices to murder.

1939–1948

The outbreak of war in September 1939 changed the Yishuv’s priorities. The struggle against the White Paper, which had been on its agenda for the past year, was replaced by fear of war. Ben-Gurion coined a slogan: “We shall fight the war against Hitler as if there were no White Paper, and we shall fight the White Paper as if there were no war.”2 It expressed the Zionist dilemma. On one hand, the great enemy of the Jewish people was Hitler, and it was necessary to fight him to save the entire spectrum of human values from barbarism and violence. On the other hand, Britain, which was leading the fight against Hitler, was now an enemy. How could the Yishuv fight on Britain’s side against a common enemy without abandoning the struggle against the White Paper?

In the end the struggle against the White Paper was shelved until better times, and the Yishuv enlisted itself in the war effort by placing at Britain’s disposal its production capacity, human resources, and military potential; 27,000 young Jews enlisted in the British Army. The Arabs, for their part, leaned toward the other side. In 1941 a rebellion led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani in Iraq endangered British rule in the region. The Mufti of Jerusalem fled to Berlin and actively participated in formulating Nazi propaganda in the Middle East, demonstrating both ideological and political identification with Nazism.

So long as Britain’s situation in the Middle East was dire, Jewish-British cooperation flourished. The Palmach, for example, was created as a force designed to help the British with intelligence gathering and sabotage. From the summer of 1941 into 1942, when it seemed that Rommel’s Afrika Korps was about to break through the British lines in Egypt, panic reigned in the British officer corps in Palestine and there was talk of withdrawal to Iraq, leaving the Yishuv in danger of destruction. Its identification with the British victory at El-Alamein in October 1942 was total, for the Zionists had no other allies. Yet none of this prevented the British from assiduously maintaining the prohibition on immigration, and violent searches for Haganah weapons continued unabated.

The Zionist leadership, headed by Weizmann, had not yet given up on the alliance with Britain. Weizmann assumed that the 1939 White Paper’s anti-Zionist policy derived from Britain’s need to obtain Arab support and maintain peace in the Middle East. He reckoned that when the war ended there would be room for a reappraisal of British policy. Prime Minister Winston Churchill was thought to be a friend of Zionism. Toward the end of the war, he set up a cabinet committee to reformulate policy on the question of Palestine, and its list of members boded well for the Zionists. Meanwhile, as Weizmann hoped that the frozen sea of British policy would thaw after the war, Ben-Gurion, chairman of the Jewish Agency Executive, shifted his focus to another Great Power—America. The support of American Jewry, the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, who seemed cordial toward the Jews, and America’s might compared with Britain’s dwindling power due to the cost of the war were three factors in Ben-Gurion’s political reorientation. Another was his deep-seated suspicion of the British, which contrasted with Weizmann’s faith in them.

At the May 1942 Biltmore Conference in New York, the Zionists stated that their war aim was to establish “a Jewish Commonwealth” in Palestine—“commonwealth” being a synonym for an independent state. To avoid arousing their Jewish opponents over an egg yet to be laid, the Zionists avoided mention of partition, as well as the issue of the Palestinian Arabs. The Biltmore Program symbolized the Zionists’ resolve to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, even if it meant a bloody conflict with the Arabs. At a time when the destinies of peoples and countries were decided by armed force, the Jews were slowly adjusting to the idea that their fight for independence would also involve bloodshed.

The war’s end did not result in the change in British policy that the Zionist leadership hoped for. The cabinet committee set up by Churchill had recommended partition, with implementation postponed until after the war. But in 1945 the Labour Party led by Clement Attlee and Ernest Bevin won a landslide victory in Britain’s general election, and Churchill’s Conservative Party was voted out. Although the 1944 Labour Party manifesto contained a pro-Zionist statement that included the transfer (population exchange) idea first raised by the Peel Commission, now that Labour was in power it had new issues to consider. Ernest Bevin was appointed foreign secretary of a strong Labour government that made some weighty decisions, such as granting independence to India. But the country had been bankrupted by a world war, and the government had to manage the transition to a peace economy and take care of the returning soldiers in an era of food and fuel rationing. The Cold War already loomed, putting additional problems on the government’s plate. In this situation the friendship of the Arab states was more important than ever; indeed the vast oil resources in the Middle Eastern deserts made them advantageous allies. And since the Palestine issue was central to relations with the Arab world, the Labour government had no intention of changing the White Paper policy.

On the other hand, the Jews had experienced the greatest trauma in their history—the Holocaust. The world, and even the Jewish people, had not yet fully digested what had happened. The Jews became aware of the atrocities only gradually, and when they did, they had difficulty dealing with them. Together with grief and trauma came anger: the enlightened world had not lifted a finger to save Jews from extermination. Although all the facts were not yet known, the Jews intuitively felt, as poet Nathan Alterman put it, that “Amidst the weeping of our children in the shadow of the gallows, / We failed to hear the rage of the world.”3

The radicalization of many American Jews—normally moderate and cautious about expressing extreme positions—revealed itself in a determined struggle to open the gates of Palestine to Jewish refugees.

Nor did the close of the war bring an end to the hardships of Eastern European Jews. The antisemitism fostered by the Nazis and their Eastern European collaborators did not dissipate. Jews who tried to return to their towns and homes were greeted with hostility and violence. In the summer of 1946 there was a pogrom in Kielce, Poland, in which some forty Jews who had returned to their hometown after liberation from the Germans were brutally murdered. A vast “migration of peoples” occurred as millions of forced laborers, prisoners of war, and refugees began moving back home. Refugees who were unable to return to their own countries remained on German soil. These were mainly Nazi collaborators, concentration camp guards, and so forth, who had nowhere to return to. Tens of thousands of Jews also remained on German soil, survivors of the infamous death marches that took place at the end of the war or of concentration camps.

All the refugees were held in the same camps under the same conditions. In vain the Jews demanded to be separated from people who only yesterday had been their persecutors and even now continued to abuse them. The British occupation authorities contended that separating Jews from non-Jews was a continuation of Hitler’s racist policies. It was only after the intervention of Jewish chaplains in the us Army that American Jewry raised an outcry, and President Harry Truman sent an envoy, Earl G. Harrison, to examine the situation in the camps controlled by the US Army of Occupation in Germany. The Harrison Report scathingly criticized the conduct of the Army of Occupation toward the Jews. It also described the hope of the majority of displaced persons (DPS) to immigrate to Palestine, and the president requested that his British ally permit 100,000 Jews to do so.

Bevin found himself in a bind. He was not prepared to change the White Paper policy, yet he could not accept strained relations with the United States, the only country capable of rebuilding Europe—not to mention its importance for engaging the Soviet bear. Accordingly he proposed an Anglo-American commission to study the situation and promised that if the commission reached a unanimous decision, he would honor it. The commission’s operative recommendation was to grant 100,000 immigration certificates to Jews in the DP camps in Germany. However, Bevin was unwilling to keep his promise, and in the meantime the flow of refugees from Eastern Europe to the DP camps in the American zone continued unabated, for the Soviet occupation was causing economic and social shock waves that affected the surviving Jews.

Hamossad Leʿaliya Bet, the Haganah’s illegal immigration arm, organized illegal immigrant ships that attempted to reach the shores of Palestine clan-destinely. As more and more ships made the attempt, British efforts to stop them increased. In August 1946 the British began stopping these ships out at sea and sending their refugee passengers to detention camps in Cyprus, which was under British rule. These voyages, as well as the forcible deportations of the illegal immigrants from the shores of Palestine, were reported in the international press and put the problem of the Jewish DPS on the world agenda. Jewish public opinion in Palestine was in an uproar, and the feelings of helpless anger aroused by the Holocaust were now directed against the British.

Nathan Alterman’s political poems highlighted the defenselessness of the Jewish refugee: “‘Mother, are we allowed to cry now?’ asked the little girl as she emerged from her hiding place.”

This very defenselessness becomes a protest against the closure of Palestine to the refugees: “When you come out from behind the barbed wire, you’ll be pursued by the army and the fleet.”

The little girl marches through Europe:

On your back exempt from pity the Joint bundle given to orphans. And in your little hand a crust of bread that UNRRA gave for tomorrow.

But she will reach the shore:

Young men, unyielding as a fist

Will carry you safely to the shore

Your arms around their neck

In the face of seventy parliaments and the sea.

Joy and happiness in your eyes

And the Law will vanquish the law.4

The entire Yishuv, moderates and radicals alike, rallied around the issue of the refugees, and the story of illegal immigration became one of the seminal myths of Israel as the country of refuge.

In Palestine the Jews mounted guerilla and terror attacks against the British, who had not yet found a formula for issuing 100,000 immigration certificates that would both satisfy the US president and not damage relations with the Arab world. The British government probably thought that if the fate of the Jewish refugees was really so close to Truman’s heart, he could amend US immigration laws and allow them to settle there. But Truman knew that such a move would be very unpopular in his own country, and the British avoided embarrassing him with a direct request.

The Zionist Executive was also in an uncomfortable position. If Bevin issued the 100,000 certificates, the Palestine question would be off the international agenda without the Jews having attained a state. But since Bevin stood fast, the struggle for the 100,000 immigrants became the struggle for a Jewish state, since it was clear that only when they had a state of their own would the Jews find refuge. Richard Crossman, a British member of parliament and member of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, later remarked that Bevin was worthy of a statue in his honor in Israel, since it was thanks to his obduracy that the Jews obtained their state.

In the end Bevin despaired of finding a solution to the Palestine problem, and the British cabinet decided to return its Mandate to the United Nations (which had replaced the League of Nations). This change was announced in February 1947, and the UN set up a Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) to reexamine the question of Palestine. The committee visited Palestine in the summer of 1947 and witnessed some dramatic events, including the arrival of the illegal immigrant ship Exodus—whose passengers were deported back to Germany by the British in a display of utter insensitivity—and terror attacks by Jewish underground groups. UNSCOP recommended the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states (see map 3), but the Arabs flatly rejected this recommendation and demanded the establishment of a majority state in Palestine.

The UNSCOP recommendations were brought before the UN General Assembly at Lake Success, New York, where a two-thirds majority was needed for ratification. The Arabs hoped that the Eastern bloc led by the USSR would thwart the resolution, but they did not take into account Soviet aspirations to weaken Britain’s standing in the Middle East. Quite amazingly—and only briefly—the Soviets changed their hostile policy toward Zionism and supported the establishment of the State of Israel. The historic UN General Assembly vote on November 29, 1947, decided to terminate the British Mandate for Palestine and establish two states, Jewish and Arab.

The UN resolution passed on a Friday evening. All Jews in Palestine were glued to their radios and when the result was announced, they flooded the streets. Zipporah Borowsky (now Porath), an American student who had come to Palestine two months earlier, described the event in a letter to her parents: “I walked in a semi-daze through the crowds of happy faces, through the deafening singing of ‘David, King of Israel, lives and is alive,’ past the British tanks and jeeps piled high with pyramids of flag-waving, cheering children. . . . I pushed my way past the crying, kissing, tumultuous crowds, and the exultant shouts of ‘Mazal Tov’ . . . to try to share with you this never-to-be-forgotten night.”5 There was a feeling of spiritual elation, a mixture of individual and public joy. But in the Arab community there was shock and mourning. The following day saw the first fatalities on the road from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv.

THE HERITAGE OF MANDATE RULE IN PALESTINE

During Ottoman rule Palestine had been part of a single polity stretching from North Africa to Iran. It was divided into several Ottoman administrative districts and was known as “Southern Syria,” with no political designation of its own. The terms Palestine and Eretz Yisrael acquired geopolitical significance only during the Mandatory period, when the government defined the country’s northern, southern, and eastern borders. The designation of the northern border took into account Palestine’s developmental needs, keeping part of the River Jordan’s water sources inside the country. Later discussions of Palestine referred to the 1920s Mandatory border, which was given the status of an international border.

Although Herbert Samuel undertook far-reaching development plans and government initiatives, it was soon clear that the government in London was not prepared to invest in the development of Palestine. The British taxpayer was not to bear the cost of maintaining the country; Palestine was supposed to generate enough income to cover British government expenditures there and even return part of the Ottoman debt. The policy that the Mandatory government had to balance its budget, dictated by London, was typical of British colonial administration all over the world.

Britain’s paramount interest in Palestine was strategic, and the British were only willing to make investments in Palestine that were linked to this interest, as occurred during both World Wars. The Mandatory government invested vast sums from its operating budget to develop transportation infrastructure. In addition to constructing the road network and railways, in the early 1930s it initiated construction of a deepwater port in Haifa with the intention of bringing in an oil pipeline from Iraq that would ensure a fuel supply for the British Mediterranean Fleet. To this end British-owned oil refineries were built in Haifa. The government encouraged construction of electric facilities on the Jordan and Yarkon Rivers. Though all this investment helped modernize Palestine and advanced agricultural and industrial development, it was also vital to the activities of a modern army.

Examination of the Mandatory government operating budget shows that administration and security accounted for more than 50 percent, whereas welfare (health and education) totaled a mere 12 percent. These proportions derived not from security problems in Palestine but from the tradition of colonial administration; the respective allocations were much the same in the contemporary budgets for India, Cyprus, and Transjordan. In stark contrast the budget in Britain itself during this period earmarked the lion’s share for welfare. This is the difference between a colony and its mother country.

Compared with the previous administration in Palestine, however, the Mandatory government must be credited with some great and comprehensive accomplishments. The development of health services, preventive medicine, and a fresh water supply, the fight against malaria, the draining of the swamps, and other infrastructure improvements enhanced both the quality of life and the life expectancy of all the inhabitants.

The Mandatory government acted in accordance with the principles of British colonial government. Most of the senior Mandatory officials had previous experience in British crown colonies, which they applied, for better or worse, to Palestine. Colonial social policy was designed to further economic progress and introduce modernization but without damaging the local cultural fabric and social tradition. For example, the Arab population of Palestine was mainly agrarian, and British initiatives to nurture, improve, and modernize Arab agriculture helped raise the standard of living in the villages and increase the population, mainly as a result of reduced infant mortality. At the same time, after an impressive initial investment in building schools in the villages, budgetary constraints halted educational development in the Arab sector. Until the end of the Mandate period, the Arab education system provided only four years of schooling to most boys and to only a small percentage of girls. In the 1930s urbanization gained momentum due to population increase, land sales to Jews, and the availability of government jobs. But all in all, the Arab village maintained its structure and traditions. While the Mandatory government was entrusted with care of the inhabitants, it did not consider itself responsible for helping them advance.