17BEGIN IN POWER

In the run-up to the May 1977 elections, Israeli television adopted the British practice of the exit poll. As voters left the polling station, they were asked to recast their vote in a sample poll. Through statistical analysis of the results, the pollsters could get an indication of the election results shortly after the polling stations closed. When the television executives saw the exit poll results, they could hardly believe their eyes. The Likud (comprising Gahal and some small parties) had won forty-four seats and the Alignment only thirty-two. At first they thought the exit poll results were wrong, but as the real results flowed in it became increasingly clear that the unbelievable had happened. For the first time since the establishment of the state, Mapai, or the Labor Party, would not be the majority party in forming the government. At eleven that evening TV anchorman Chaim Yavin announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, an about-turn!” coining a Hebrew phrase that took its place in Israeli politics and culture.

Likud leader Menachem Begin waited until all the results were in before going with his wife, Aliza, to Likud headquarters, Metzudat Zeʾev (Jabotinsky), where the victory celebrations were already in full swing. Chaim Yavin described the scene, with men in suits and ties replacing the Alignment people and their informal attire; the sloppy style of dress typical of leftists was no more. The building shook to the rhythmic chanting of “Begin, Begin.” Begin put on a yarmulke and intoned the Shehehiyanu blessing (used to celebrate special occasions), thanked his wife, children, and grandchildren, and then quoted from President Lincoln’s second inaugural address: “With charity for all; with firmness in the right . . .” The yarmulke, the blessing, the family references, the use of ceremony were previously unknown in Israeli politics. The anchorman hit the nail on the head when he smilingly remarked, “We’ll have to get used to a new style.”

Begin is apparently the only leader in the history of democracies who lost eight elections and won the ninth. When the Etzel was disbanded he founded the Herut party, a fighting opposition to the rule of Mapai and the left. The transition from underground fighter—or, as the international press liked to call him, “terrorist”—to parliamentarian did not gain Begin the public recognition he had hoped for. Until the 1960s his party won fewer than twenty Knesset seats, whereas Mapai won more than forty. Begin had difficulty surmounting the legitimacy obstacle, and Ben-Gurion did everything he could to prevent him from achieving public trust. The Herut platform, which asserted, “The Jordan has two banks, and both belong to us” (in the words of Jabotinsky, the founding father of Revisionism), aroused fear in Israelis of an irredentist party that would lead the nation into war.

Over the years there was a slow, almost undetectable retreat from this maximalist slogan that reduced the claim to the west bank of the Jordan; even this represented an aspiration that did not mandate action. At the time the 1949 lines were the accepted borders. When Gahal was founded in 1965 (as noted, a union of Herut with the liberals, a centrist middle-class party), Begin refused to stop mentioning the territory of the historical Land of Israel (reaching as far as the Jordan), but the liberals viewed this as saber rattling that was out of line with their moderate foreign policy. As a compromise the issue was mentioned in the introduction to the platform as a commitment solely of Herut, not the united party, to the “integrity of the homeland” doctrine. The slow retreat from commitment to Greater Israel represented an acceptance that, for the vast majority of the Israeli public, Greater Israel was a distant dream, not a political platform. As noted before, Ben-Gurion’s objective was to prevent the man whose militant aspirations and ways of operating he considered a danger to Israel’s very existence from being accepted as a legitimate actor on the political stage. “The man sitting next to Dr. Bader” [in the Knesset] is how Ben-Gurion referred to Begin. Ben-Gurion’s phrase “without Herut and Maki” was aimed at preventing the radical right and left from joining coalitions. For several years the Ministry of Defense refused to recognize that Etzel and Lehi veterans were entitled to pensions and allowances equal to those received by their Haganah counterparts. This unjustifiable but temporary discrimination later became the source of an entire myth of discrimination.

Begin had adopted a political style that was unacceptable in Israel. In a speech he gave at a demonstration against the reparations agreement with West Germany in January 1952, he fired up the audience with expressions vilifying Ben-Gurion and an implied threat of violence. After the speech, as described in earlier chapters, the demonstrators marched to the Knesset building and stoned it, ironically just as Begin himself was addressing the plenum. Begin was penalized with a three-month suspension from the Knesset. After that demonstration he moderated his rhetoric and increasingly stressed his commitment to democracy and the rule of law. He campaigned for the 1959 elections to the Fourth Knesset under the slogan “From Opposition to Government,” holding well-attended public meetings all over the country. On the day before Election Day that year, he toured the poor neighborhoods of Tel Aviv in an open car, escorted by motorcycle outriders. This idea had been introduced by the Herut campaign manager, who got it from the United States, but in Israel it was seen as the exhibitionism of a Mussolini-style right-winger.

Begin infused his speeches with biblical expressions, prophetic spirit, and high-register rhetoric disconnected from reality. His critics claimed he was pompous, but he aroused enthusiasm among the masses. On all domestic policy issues he was ready to use demagoguery against the government. On foreign policy he was prepared to support every belligerent action by the government but not withdrawals or concessions. More than once his repeated failure to gain the people’s trust aroused dissatisfaction in his own party, but each time his leadership was challenged he promptly expelled the challenger from the party. Herut was a “family” party, whose leadership had been forged when the Etzel was underground. There was an intimacy among the veterans, who accepted Begin’s leadership unquestioningly. Most of the members came from Poland, and Begin’s authoritarian style matched the conventional practice in the nationalist movements of that country between the two World Wars.

Begin and Herut’s breakthrough from the wilderness of delegitimization to the center of the political arena took place on the eve of the Six-Day War. As the country’s fate seemed to hang in the balance, Begin—in a belated recognition of Ben-Gurion’s extraordinary powers of leadership—magnanimously proposed that Ben-Gurion be brought back from retirement in Sdeh Boker and into the government. Ben-Gurion did not return to government, but that was the beginning of a process of conciliation between him and Begin, whose Polish nobleman’s mien charmed the old leader’s wife, Paula, who had a soft spot for him. In the negotiations over creating a national unity government on the eve of the war, the NRP demanded a place for Gahal, and for the first time Begin was appointed one of its ministers without portfolio. In this way Begin and Herut emerged from the deep freeze and became suitable political partners. When Golda Meir formed her government in 1969, she invited Gahal and Begin to join it, lending real credence to their legitimacy; while the earlier appointment in 1967 could have been construed as an emergency appointment, this was recognition of Begin and his colleagues as worthy members of government.

The Six-Day War transformed the Herut platform from a distant ideal into reality. The West Bank and the Gaza Strip were in Israel’s hands. Henceforth Begin worked assiduously to ensure state rule over all of the historical Land of Israel. He was a party to the government decision of June 19, 1967, expressing willingness to concede Sinai and the Golan Heights in return for peace agreements. But he did not agree to a similar arrangement with Jordan regarding the West Bank. In 1970, when the government of Israel informed un mediator Gunnar Jarring that it was willing to implement un Security Council Resolution 242, which included the principle of nonannexation of territories occupied in war, he forced Gahal to leave the government by threatening to split the party if his stand was not accepted.

The Yom Kippur War was the momentous event that brought about the demise of labor movement rule. The public perceived the mehdal as an expression of the Labor Party’s political ineptitude, and this led to a loss of the faith that was the party’s most valuable asset during its years of rule. People viewed it as the natural ruling party, which knew how to steer the ship of state to a safe haven. For the first time the war raised doubts about this image, which until then had not wavered in the face of opposition attacks from left and right alike. The Rabin government began its term of office under the heavy cloud of these doubts. Its weakness, the internal struggles between Peres and Rabin, and the cases of corruption exposed during this period damaged the government further. The media, particularly television—which until the Yom Kippur War had displayed moderation in criticizing the government—now embraced the practices formulated by American television during the Vietnam War and the Watergate affair. Television became a central tool for exposing the government’s flaws and weaknesses, and through pithy and even venomous satire it contributed to undermining the Labor Party’s image as the party destined to rule. In the 1977 elections voters on the left shifted mainly to Dash, which won fifteen seats and became the third-strongest party. This vote expressed labor voters’ disgust but did not represent an essential change in their political worldview—certainly not acceptance of Begin’s positions on Greater Israel.

BEGIN’S FIRST TERM AND THE CAMP DAVID ACCORDS

Begin brought to government an authoritarian style unknown in Israel since Ben-Gurion’s time. After the previous government’s weakness this style seemed like a breath of fresh air, inspiring confidence and restoring the sense that the captain was indeed safely navigating the ship. Begin was a man of opposites, and he was either admired or despised. He was capable of grand gestures yet also of pettiness. A lawyer by profession, he scrupulously respected the courts and the rule of law. But he was also capable of indulging in endless polemics and legal hairsplitting. He was a man of honor who boasted that he always kept his promises, but in fact he had no qualms about breaking them when he considered it necessary. He vowed that no Arab would be dispossessed of his land as a result of Jewish settlement in the occupied territories, and abided by that promise. At the same time, he visited the settlers at Elon Moreh and declared, “There will be many more Elon Morehs.” Always conscious of the importance of symbols, Begin insisted that official publications not describe the West Bank as “occupied” or “Israeli-held” territories. Instead they had to use biblical names that consolidated the Jews’ connection with these areas from time immemorial: Judea and Samaria.

The coalition Begin formed included the NRP (which won twelve seats) and Agudat Yisrael. Dash joined later. This was the first time since 1952 that an ultra-Orthodox party was a coalition member. In contrast with the heritage of Jabotinsky, which was essentially secular, Begin observed Jewish tradition. Even when he did not observe the commandments, he adopted a style that projected sympathy and respect for tradition. His speeches were peppered with “God willing” and verses from the prayer book; his head was always covered on occasions that called for it, and also on those that did not. When the ultra-Orthodox requested that El Al not fly on the Sabbath, he quickly acceded to this request as self-evident. He increased allocations to the yeshivas, resulting in the growth of the class of unemployed yeshiva students to a scale previously unknown in the history of Israel. He also canceled the cap on the number of yeshiva students exempt from military service (which Ben-Gurion had set at 400 and Dayan increased to 1,500); since then the number has increased to tens of thousands.

Begin had a far higher level of Holocaust awareness than any prime minister who preceded him. As one who had left Poland with the outbreak of World War Two and whose family perished there, he identified with the annihilation of the Jewish people under Nazi rule with every fiber of his being. As a prime minister committed to the interests of the country, he relinquished his tough stance against relations with Germany—one of the European countries most friendly to Israel—but the images that shaped his psyche were associated with the Jewish trauma of World War Two. After the elections, when he met with American Jewish leaders—mostly liberals concerned about his nationalist militancy—he won them over with his Yiddishkeit, his profound connection to the Jewish past, the Yiddish he sometimes used, and his deep identification with the Jewish people. He spoke not of “Israelis” but of “Jews.” Subjected to international criticism over Israel’s bombardment of Beirut in the 1982 Lebanon War, he evoked Holocaust images. When the media published an image of a wounded Palestinian girl, he placed on his desk the well-known photograph of a Jewish child in Warsaw facing armed, jackbooted German soldiers with his hands raised. He likened Arafat to a new Hitler plotting the annihilation of the Jewish people. During his critical meetings with President Carter, he made use of deep pathos, evoking the memory of his lost family, which cast a deep silence over the room.

Some viewed such behavior as exaggerated theatricality, a cheapening of the Holocaust that vitiated its uniqueness and moral power. But others saw it as an extraordinary adeptness at persuasion that put Begin’s adversaries in their place. The popular 1980s slogan “The whole world is against us” was a reaction to the unbridled, one-sided criticism leveled against Israel by the world media during the first Lebanon War, criticism spiced with genuine antisemitism. But it was also influenced by Begin’s leadership style, which framed Israel and the Jewish people as the constant targets of unfair judgment by the nations of the world, which were resolutely trying to damage Israel. This was a return to traditional Jewish ways of thinking, in the vein of “It is a given law; it is known that Esau hates Jacob.”

Begin’s rise to power marked more than a change of government. It symbolized a move to center stage of new classes, another culture, a different historical narrative. Begin touched a sensitive spot in all those who saw labor movement Israeliness as arrogant, alienated, and alienating, as an identity contrary to their own. The immigrants of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly those from North Africa, brought with them a heavy load of disadvantages that became yet more burdensome during their absorption difficulties in the maʿabarot and development towns, as they were required to quickly adopt a modern, secular, Western culture. One component of this shift was the breakup of the patriarchal family, which entailed diminished status and an erosion of respect for the father. For these immigrants Begin, the underdog of Israeli politics, represented the man who had succeeded in turning the tide. He wore a suit, spoke politely, and demanded courteous behavior—accepted practice in elite Mizrachi circles. His authoritarianism was a replacement for the eroded authority of the father. His oratorical ability was unparalleled, and his willingness to stand up to the whole world spoke to them. But what spoke to them even more were his virulent attacks on the Alignment—the source of all their absorption hardships—blaming it for all the real and imagined humiliations they had suffered. Many Mizrachi Jews enthusiastically received Begin’s demonization of the Alignment in his speeches; he was putting into words all their feelings of being discriminated against. His use of religious idioms and respect for religion were aligned with their value system, which contrasted sharply with insolent sabra secularism. Begin’s “Jewishness” and his tendency to emphasize tradition lent him a certain familial intimacy for the Mizrachi Jews, most of whom kept a warm place in their heart for family tradition.

Begin placed the Holocaust firmly at the center of Israeli discourse. Some Holocaust survivors took this as an opportunity to demand their rightful place in the national narrative, recognition of their contribution to the establishment of the state and their participation in the War of Independence. But many others joined the campaign demonizing the old Israeliness. The survivors’ claims covered a wide range. There were allegations that during the World War the Yishuv leadership was not sufficiently aware of what was happening in Europe and did not try to help the European Jews during the Nazi occupation; that in Israel the survivors had faced a rejecting and disdainful attitude, resistance to hearing their stories, and accusations that they had “gone like lambs to the slaughter”; and that the memory of the Holocaust had been suppressed in the first decades after the World War.

This was a political struggle that became a fight for commemoration. As we have seen, allegations that the Yishuv leadership did not stand up and fight for European Jewry had been made by the Etzel as early as the 1940s. After the fight against the reparations agreement, Herut adopted an image as the party that had cared for the Jews of Europe, unlike hard-hearted Mapai, which was prepared to sacrifice national honor for German money. At the same time, at the Kasztner trial the right-wing attorney Shmuel Tamir presented the survivors as collaborators with the Nazis, the diametrical opposite of the proud sabras. In his telling only the ghetto fighters were worthy of respect. The Eichmann trial transformed these images and turned the Holocaust into a central element of Israeli identity.

Now Begin positioned the Holocaust as a unifying factor with respect to the old Israeli identity, opposing that identity with a new one whose images were far more connected with Diaspora petit bourgeois culture (which he extolled) than with the supposed proletarianism of the labor movement. He sought to build a new genealogy that no longer relied on Petach Tikva and Sejera, à la Ben-Gurion, but on Warsaw, Berdichev, and Casablanca as the sources of Israeli identity. Furthermore, if until then the Etzel and Lehi had been excluded from the story of the establishment of the state, now the record was set straight. According to Begin, without the Etzel’s fight against British rule the state would not have come into being; Mapai, he contended, had conceded the integrity of the country out of its weakness and lack of resolve. Begin cast himself as the true patriot who had prevented an internecine war during “the hunting season” and the Altalena episode, whereas the left had no qualms about handing over the underground heroes to the British. Begin and his colleagues inculcated this narrative, a combination of truth and lies, hyperbole and self-persuasion, through speeches to an audience of admirers, most of whom had not even been in the country when these episodes took place and accepted this propaganda as though Moses had brought it down from the mountaintop. The extent to which Begin used the battles of the past to ensure legitimacy in the present can be seen in his creation of a commission of inquiry to reexamine the 1933 murder of Chaim Arlosoroff, head of the Jewish Agency’s Political Department. The Revisionist narrative described the accusation that members of Betar had committed this crime as a “blood libel.”

“The fighting family”—Begin’s circle of close Etzel comrades, who had accompanied him down the thirty-year-long road during which he did not rise to power—was an exclusive club that accepted no one who did not have the same background and the same education and worldview formulated in the Etzel. The problem was that in order to become a party of the masses, Herut, and later Gahal, had to open itself to the new immigrants. Some of these immigrants had been members of Betar abroad, raised on the worldview whose foundation was Greater Israel, anti-leftism, national honor, and adulation of Jabotinsky as founding father. But for most North African immigrants, it was the encounter with Begin that offered the prospect of leadership, an opportunity for advancement and belonging, and a link with the founding myth of the state. The opening of Gahal, and later the Likud, to the activists of the development towns and distressed neighborhoods was not well received by the old Betar elite, which felt rejected by the newcomers, who in addition did not always fit the image of “Hadar,” which Jabotinsky had defined as “outward beauty, respect, self-esteem, politeness, faithfulness. . . .” But as the years went by the majority of the old leaders were no longer able to manage the party. Researchers Uri Cohen and Nissim Leon contend that on the eve of the about-turn, the Mizrachim held a large majority in the party central committee. Membership on this committee was a reward for people active in the local party branches. These branches created party loyalty among a young, dynamic elite that rose from the rank and file and was the mobilizing force that brought masses of voters to the polling stations. They were the people who carried Begin to power.

By contrast with the Likud’s dynamism, the Labor Party was tired, crumbling from within, lacking authoritative leadership, and suffering from a loss of self-confidence. It did not go on the attack and exploit Likud scandals, such as the Tel Hai Foundation deficits that Begin tried desperately to pay off in the year before the about-turn. To Labor Party supporters Begin’s theatricality and rhetoric looked like unconvincing demagoguery, but no one among the party’s membership was capable of fighting him with his own weapons. The restrained, matter-of-fact style of the native-son generation, which was now part of the movement’s leadership, could not compete with Begin’s dramatics, which engaged his audiences’ emotions and expressed their desires. The doubts he cast on the labor movement’s place in the history of the Yishuv and the state stunned its members.

The Labor Party of the 1970s, which boasted of its social-democratic leanings, was a party of intellectual elites, liberal professionals, and upper-class salaried workers. It was not a party of the working masses; they voted for the Likud. The Labor Party’s socialism involved a high level of state involvement in the economy with the goal of achieving maximum equality. This trend diminished after 1967, but Israel remained one of the world’s more egalitarian countries. Although the state provided an impressive social safety net for its citizens, it did not turn this benefit into all-conquering propaganda. The party’s ideology centered on the individual’s commitment to the state and spoke of the citizen’s obligations but not his or her rights. It fostered “the common good” but not the interests of the individual. For his part Begin championed a discourse of individualism, grounded in the question “What does the state give me?” not “What do I give the state?” In his Knesset speech presenting his government, Begin asserted that “much work, perhaps even hard labor, is imposed upon us. We, my colleagues and I, shall do that work with dedication, loyalty, in good conscience, with a sure heart and in the belief that with God’s help we shall ameliorate the lot of our people.”1 This statement contravened the entire ethos of the labor movement, which was based on belief in the masses rising to the challenge—not on a leadership that was their patron.

Begin’s first government disappointed the Herut veterans. The major portfolios went to people who had not come up through the party ranks. Ezer Weizmann, architect of the Israeli Air Force and nephew of Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, who had managed the Likud’s successful election campaign, was appointed minister of defense. Minister of Finance Simcha Ehrlich was a bland moderate from the liberals. Ariel Sharon, whose party Shlomzion with its one seat swiftly joined the Likud following its victory, was appointed minister of agriculture. (Begin was quoted as saying that if Sharon were given the defense portfolio, he would surround the Knesset with tanks.) Sharon took upon himself the task of expanding settlement in the occupied territories. When Dash joined the government, Yigael Yadin was appointed deputy prime minister. Begin surprised the Israeli political system by bringing in Moshe Dayan, who had been vilified since the Yom Kippur War, from the political wilderness and appointing him foreign minister. It was a brilliant move designed to lend the government international legitimacy.

The Western countries were stunned by the Israeli election results. Begin was branded a dangerous extremist. Time noted that “Begin” rhymes with “Fagin,” a blatantly antisemitic remark to which Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek responded, “Time equals slime.” A boatload of Vietnamese refugees who had sailed from port to port, since no country would take them in, found safe haven in Israel on Begin’s orders; he saw them as a reminder of the Jewish tragedy of World War Two and the world’s indifference toward it. This charitable act neutralized Begin’s terrorist image in the world press, particularly in Britain. In light of the attacks on him and the fears he aroused in the world media, his moderateness and courtesy were a pleasant surprise. But what mainly worked in his favor was the peace process.

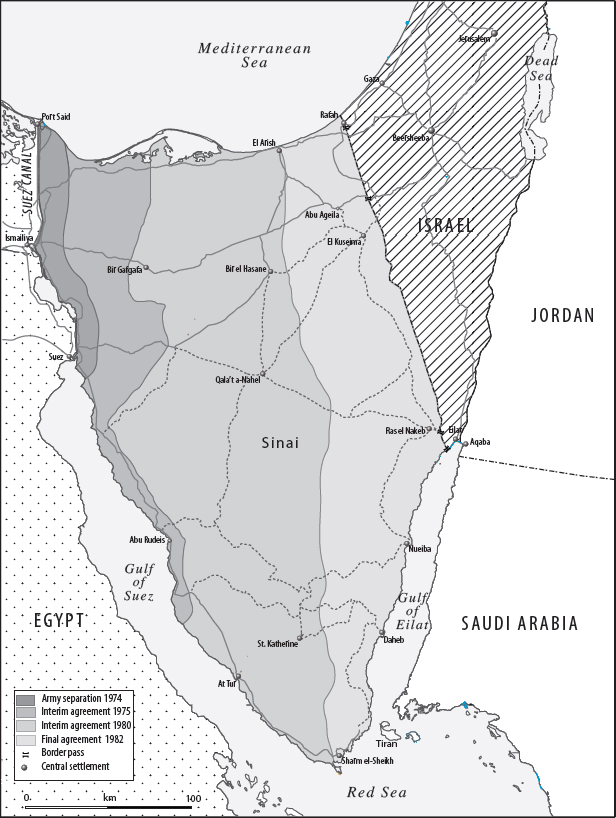

Begin did not believe in partial arrangements with the Arab states and had vehemently opposed the interim agreements Rabin achieved. He wanted a historic breakthrough: a peace agreement with the biggest, most important Arab state—Egypt. Hints that he was willing to compromise on territory can be detected in the platform he dictated to his party in January 1977 before his rise to power. It expressed an intention to compromise on Sinai and the Golan Heights while asserting that west of the River Jordan there would be no foreign rule but rather autonomy for the Arab inhabitants. Dayan’s appointment as foreign minister was a signal of Begin’s interest in negotiating with the Arab states, above all Egypt. At his first meeting with President Carter, Begin said that he accepted un Security Council Resolution 242—to which his opposition in 1970 had caused his resignation from Golda Meir’s government. He initiated a meeting with Romanian president Nicolae Ceau¸sescu, and sent Moshe Dayan to meet with King Hussein, the Shah of Iran, and King Hassan II of Morocco, under whose sponsorship Dayan met with Egyptian deputy prime minister Hassan Tuhami. The cumulative effect of these meetings led to the greatest surprise of the century: Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem.

In an address to the Egyptian parliament on November 9, 1977, Sadat laid aside his written text and added two short sentences on negotiations with the Israelis: “I am willing to go to the ends of the earth for peace, even to their house, the Knesset, and talk to them. We have no time to waste.”2 This declaration was greeted with thunderous applause, which showed that the audience had not fully comprehended its revolutionary significance. Begin understood it himself only when a journalist pressed him for his response, saying that all the news agencies had already circulated the dramatic news. Always at his best when called upon to play a role in a drama, Begin did not disappoint: “I will gladly meet with Sadat anywhere, even in Cairo, and should he want to come here he will be welcomed.” These words were construed as an official response and broadcast by Kol Yisrael.

The drama was heightened a few days later when cbs broadcast parallel interviews with the two leaders, presenting the adversaries as partners in negotiations that would take place within a few days. In his interview Begin used the words that became a slogan: “No more war, no more bloodshed.” The two protagonists in this performance were aware of the effect of its symbolism, the importance of gestures, the groundbreaking nature of their moves, and the power of their psychological influence. Sadat believed in the need to break down the psychological barrier of the Israelis’ lack of trust in Egypt, and his visit to Jerusalem and appearance in the Knesset were aimed at eliminating that barrier. The international media turned the event into a drama of paramount importance that reached every home, making Sadat and Begin familiar cultural heroes in the Western world.

There followed days of sublime intoxication. The Israelis could not believe their eyes. The man who symbolized “not one inch,” absolute refusal to compromise, had invited Sadat to Jerusalem—and precisely at this time, when Begin was prime minister, Sadat was willing to accept the invitation. Begin’s popularity soared. There were voices, such as that of Chief of the General Staff Mordechai Gur, expressing fears of an Egyptian deceit portending an attack such as that of 1973, but they were quieted by Begin and drowned in the enthusiasm engulfing the Israeli people. On November 19, 1977, Sadat’s plane landed in Israel. The entire nation was glued to its television sets, watching the incredible scene of the Egyptian president’s plane touching down in Lod, with red carpet and guard of honor awaiting him, together with government ministers, former prime ministers, leaders of the opposition, and other dignitaries. Israeli and Egyptian flags fluttered in the breeze. The aircraft’s door opened and the Egyptian delegation began descending the steps. Last to appear was President Sadat, elegant and erect. Begin welcomed him and escorted him down the red carpet. The citizens of Israel were ecstatic. If Sadat wanted to persuade them of his peaceful intentions, he had won them over in a single dramatic gesture. In the era of television, politics was a drama played out to an audience of millions, and Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem was the height of drama. When somebody remarked that the story would end with the two heroes receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, Golda Meir quipped, “I don’t know about the Nobel Prize, but they certainly deserve an Oscar.”

As Israeli journalist Teddy Preuss wrote, the peace process began with a climax—Sadat’s visit—and all that followed was somewhat of an anticlimax. And indeed nothing compared with the impact of Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem. In an unofficial conversation between Begin and Sadat at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem that same evening, both sides undertook to abandon the path of war and espouse negotiation to resolve problems from then on. Israel would withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula, which would remain demilitarized. This unwitnessed conversation later created controversy. Begin claimed he had spoken of transferring sovereignty only over part of Sinai, since he intended to keep the Israeli airfields and the settlements in northern Sinai and the Rafah Approach, including the town of Yamit. Sadat contended that he had not committed Egypt to demilitarize the whole of Sinai, but only the area east of the Mitla and Giddi passes. These issues emerged once the elation over the historic meeting had died down and the two sides embarked on negotiating the details of the agreement.

The day after Sadat’s arrival in Jerusalem, it was already clear that the negotiations would be arduous. Sadat delivered a tough address in the Knesset in which he demanded Israel’s withdrawal from all the territories occupied in the Six-Day War and “a just solution of the Palestinian problem”—two demands that were unacceptable to any of the Zionist parties. Begin responded with a vigorous speech reiterating his willingness to work for peace with Egypt. With respect to the demand to restore the Palestinians’ rights, he spoke of the rights of the Jews and the lessons of the Holocaust, but still said that for his part “everything is open to negotiation.” Both sides clung to what the other wanted to avoid: Sadat insisted on linking peace with Egypt and peace with Syria and Jordan, as well as “the rights of the Palestinians” (which he did not define in detail), and Begin sought a separate peace agreement with Egypt while adhering to the principle of Greater Israel and avoiding foreign rule west of the River Jordan.

If in the initial enthusiasm it seemed an agreement could be reached swiftly, this possibility dissipated as the discussions went on. Pressure on Sadat from home and abroad increased. The Arab states attacked both him and his peace policy. In Egypt the opposition’s voice was raised in a union of young left-wing intellectuals with the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, and Sadat did not feel he had the freedom to relinquish any of his principles. Begin, for his part, was ensnared in his lifelong loyalty to the Greater Israel ideology. The negotiations became protracted and exhausting, eroding both sides’ belief in the peace process. As time went by, what began as a sense that the wings of history were beating wound up with the parties mired in clauses and subclauses, with no sign of a breakthrough.

From a very early stage in the negotiations, Begin tried to circumvent the obstacle of the Egyptian demand to establish a Palestinian state in Judea, Samaria, and the Gaza Strip, which for him was totally unacceptable. The formulation he brought to the table involved granting autonomy to the Arab inhabitants of the occupied territories, which Israel would not annex. There would be no foreign rule west of the Jordan, but neither would Israel claim what Begin viewed as its historical right to sovereignty over Greater Israel. From Begin’s point of view, he was making a tremendous concession. The idea of autonomy was in line with his political outlook, which drew on Jewish experience as a national minority in Eastern Europe, where the Jews had sought autonomy but not sovereignty.

Begin proposed to Carter, and later to Sadat, that Israel would abolish military government in the occupied territories and grant autonomy to their inhabitants. They would be able to manage their lives as they chose, but Israel would reserve the right to purchase land there and settle on it, and would also administer security. This formulation appeared and reappeared in various versions at the negotiating table. President Carter, who was a partner to the negotiations and became more deeply involved once it emerged that the process was bogged down and needed US help to extricate and advance it, supported Palestinian rights to self-determination and backed Sadat in this goal. Begin was entrenched in his positions of not allowing the PLO to gain a foothold in the occupied territories and not committing himself to anything that might be construed as agreeing to a Palestinian state, especially the return of the 1948 refugees to the territories. A main bone of contention was Jewish settlement in the occupied territories. Begin refused to commit himself to stopping settlement, but Sadat would not move forward until agreement was reached on this matter.

A strong protest movement against Begin’s policy emerged in Israel, asserting that the country was missing an opportunity for peace with Egypt because of the Greater Israel ideology. The movement appeared in March 1978 when the negotiations were deadlocked. It began with a letter to the prime minister signed by 348 reserve officers, many of whom were combat veterans. The writers expressed grave concern over the deadlocked negotiations, which could lead to another war in which they would be forced to shed their blood. The letter was published and aroused broad public support. Within a few days a voluntary movement of young people was organized and joined by tens of thousands. Denying any political affiliation, the movement had one demand: Peace Now. Its bumper-sticker slogan, “Better Peace than the Greater Land of Israel,” appeared on thousands of cars all over Israel. Its demonstrations drew tens of thousands. The movement was an expression of the tremendous impact of Sadat’s visit on Israeli public opinion.

As October 1978 approached—marking the date of the renewal of the UNEF mandate in Sinai, and a year since Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem—grave fears emerged in Jerusalem and Washington that Sadat might withdraw from the peace process and undertake a spectacular military action, as he had done in 1973. President Carter decided on a dramatic action of his own. He invited both sides to Camp David for a conference that would take place with the delegations completely isolated from the media, in the hope that the intensive interaction would yield an agreement. “It proved to be the decisive, most difficult and least pleasant stage in the Egypt-Israel peace negotiations,” Moshe Dayan wrote. “All three parties had to resolve agonizing psychological and ideological crises in order to reach an agreed arrangement.”3 The Camp David summit lasted thirteen days, from September 5 to 17. Until the last moment there was no certainty that it would end with an agreement. Each day brought its own crisis, each day the feeling that the two sides had reached an impasse and it would be better to go home. And each day someone called for a little more forbearance, a little more patience, in order to reach a positive conclusion. Both sides feared being accused of causing the failure of the talks, and both sought American support for their positions. This gave President Carter and his aides wiggle room, enabling them to exert pressure on both sides to ultimately make the required fateful decisions. But beyond the tactics and strategies, what tipped the balance was the basic desire of both Begin and Sadat to bring a peace agreement home to their people. This desire enabled them to surmount the obstacles of mistrust, the internal and external pressures, the difficulty of changing their entrenched positions and taking a risk.

Two framework agreements were signed at Camp David, meant to form the basis of the peace treaty whose details were to be agreed upon within three months. Begin agreed to suspend new settlement during the three-month period. This undertaking was later construed by Carter as a total commitment, which Begin ostensibly breached. But it seems that the Egyptians understood the undertaking to be limited.

One framework agreement dealt with the principles of the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. With a heavy heart and grave misgivings, Begin agreed to relinquish the settlements in Sinai and the Rafah Approach, as well as the airfields. As a sort of compromise with himself, Begin stated that the Knesset would have to ratify these concessions. The Americans eased this particular burden by agreeing to build two alternative airfields in the Negev, to be completed before the withdrawal. The American early warning station in Sinai would be dismantled, but UNEF would remain there and be removed only with the agreement of the two sides and the unanimous agreement of the Security Council. Sinai would be only partially demilitarized, to the east of the passes, but the sides would be separated by a wide buffer zone. For their part the Egyptians agreed to begin normalizing relations—which they had initially said would only happen after an Israeli withdrawal from the whole of Sinai—and that when the first stage of the withdrawal was completed (nine months after the signing of the treaty), the sides would exchange ambassadors. The Suez Canal would be opened to Israeli shipping, and Egypt would establish trade relations with Israel, including the sale of oil.

The second framework agreement covered the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Egypt recognized Israel’s security needs in both areas. Israel agreed to terms it had never before accepted. It undertook to grant full autonomy to the Palestinians in the occupied territories, while reducing Israeli military government there. Autonomy would last five years, after which negotiations would be held on the future of the territories. Israel reserved the right of veto on security matters there, nor did it waive its right to claim sovereignty over the area. But it was also stated that any solution to the problem of the territories must recognize “the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people and its rightful claims” and that both inhabitants of the territories and nonresident Palestinians would take part in any negotiations on the area’s future.

The Camp David Accords were not greeted with the same enthusiasm as Sadat’s visit. In Israel and Egypt alike, the treaty’s opponents highlighted the concessions the leaders had made, not their achievements. In Israel the decision to withdraw to the international border and to the dismantling of the settlements and airfields was received with incredulity. Giving up the settlements went against Begin’s promises on the eve of the summit and contravened the Tel Hai myth, according to which “One does not give up what has been built.” Actually there were settlements that had been abandoned for various reasons and others that Israel had been forced to give up in the War of Independence. But the voluntary surrender of settlements that had been built by government decision was unprecedented.

Although Begin would not withdraw from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, it was clear that the withdrawal from the Sinai and Rafah Approach settlements was a portent of what was to come: settlements are not sacred, and just as they can be established, they can be dismantled. The threat to the settlers was obvious, and they wasted no time reacting to it with vehement opposition to the agreements. Moreover, in the twelve years since the 1967 war, Israelis had been hearing about the importance of the strategic depth that Sinai gave the country, and now Israel was conceding it in one fell swoop. It was now Begin’s close friends and movement comrades who vigorously attacked him. The achievements of the peace treaty and the normalization of relations with the most important Arab state were overshadowed by the slaughter of Israeli sacred cows that had been nurtured for years. Sadat did not have an easy ride either. His having obtained a promise of a complete Israeli withdrawal from Sinai did not mollify the opponents of peace in Egypt, nor did it lead to moderation of the attacks against Sadat by the other Arab states, including the pro-Western ones.

The Knesset debate on the Camp David Accords was raucous. Only Begin, with his authority and standing in his party, could have compelled the majority of Likud members to ratify the accords. “The nation is suffering birth pangs. True, every great venture is born in anguish,” Begin responded to the right’s attacks. “This is the greatest turning point in the Middle East, which has come with the possibility of signing a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt. The anguish does not surprise me. I have no complaints about the demonstrations.”4 Even the NRP, most of whose members voted in favor of the accords, did so because it trusted that if Begin had decided to withdraw it was because he probably had no alternative. The Labor Party and Dash supported the accords, although with reservations about one clause or another. The chance of peace outweighed the numerous concessions involved.

This was not the end of the chapter. Now the framework agreements had to be formulated into a final peace treaty, and the problems left open by the vague wording of the Camp David Accords came to the surface. Israel insisted that normalization of relations should commence at the time stipulated, irrespective of when the autonomy negotiations with the Palestinians were concluded. Egypt demanded the opposite. This was another version of the basic discussion: was the peace agreement between Israel and Egypt linked to the autonomy agreement, or was there no linkage between the two? Israel demanded removal of the linkage. Egypt insisted that it be kept. Egypt had mutual defense treaties with Arab states in the framework of the Arab League. Israel demanded that priority be given to the peace agreement with it over Egypt’s Arab League commitments. Israel was concerned that should it respond militarily to Syrian or Jordanian provocation, Egypt would be duty bound to come to their aid and the peace agreement would collapse. Egypt feared that a commitment to giving the agreement with Israel priority would be seen as betraying the Arab cause.

In addition to these basic issues, there were practical problems such as supplying oil to Israel once the Sinai oil fields were evacuated. The American-mediated negotiations, held at Blair House in Washington, ended in stalemate. A further round of talks also ended in failure. It was only when President Carter flew to the Middle East and threw all his weight and prestige onto the scales that he succeeded in facilitating a breakthrough, after the two sides had almost despaired of surmounting the obstacle posed by the final details. The treaty was brought before the Knesset for ratification on March 20, 1979, and provoked one of the most protracted debates in the history of the House, but the treaty was eventually ratified by a decisive majority. In his speech from the podium, Dayan said, “The Egypt-Israel peace treaty . . . is not a pastoral idyll. . . . But it is a realistic peace treaty set in the context of current realities, and designed to bring about relations between two neighboring countries.” From the Arab standpoint it was an acceptance of Israel’s existence.5 On March 26, 1979, about a year and a half after Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, the peace treaty was signed on the White House lawn.

The treaty stipulated dates for a withdrawal in stages from Sinai, with Israel remaining in the eastern part of the peninsula and not vacating settlements and airfields until the completion of a two-year trial period. During this period negotiations on Palestinian autonomy would be held. Normalization of relations commenced immediately after the first stage of the withdrawal, and ambassadors were exchanged. Over the next two years the treaty faced some difficult tests: Sadat’s assassination, Israel’s war in Lebanon, and the collapse of the autonomy talks. But it held firm and is in force to this day. The majority of Egyptian elites—including intellectuals, media figures, and religious leaders—never became reconciled with Israel. Nor did the peace between the two governments extend to their populations, with cultural exchanges and friendly relations. Yet the Middle East seems different since then, and the peace between Israel and Egypt lies at the basis of its stability.

The peace treaty with Egypt was the zenith of the Begin era. He gained stature both at home and throughout the world. Together with Sadat he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. But within his own bloc he found himself under attack for surrendering the settlements and recognizing the Palestinians’ legitimate rights and just demands. He had difficulty facing the settlers, since in his eyes they were the pure, idealistic element of the right. While he dismissed criticism from the left, criticism from the right hurt him; his heart was with Greater Israel and the settlement enterprise. Minister of Agriculture Ariel Sharon adopted an aggressive settlement policy that included establishing settlements in the heart of Arab-populated areas, in order to thwart the possibility that one day a Palestinian state would be established. In contrast, Minister of Defense Weizmann wanted the settlements built entirely in large blocs without expropriating land. Dayan asserted that although it was permissible for Jews to settle anywhere in the Land of Israel, settlements with no security importance should be avoided. The government accepted Sharon’s proposal that settlements should be created wherever possible, and Begin was inclined to support him, even when his plans deviated from what the government had approved. The opposition of Yadin, Dayan, and Weizmann, who represented more moderate positions within the government, was not pleasant to him.

Begin appointed Minister of the Interior Yosef Burg to chair the autonomy talks, thus signaling that the West Bank was an internal Israeli matter. It was also a signal to Dayan that his role in the government was over. He resigned six months later. Begin replaced him as foreign minister with the former Lehi leader Yitzhak Shamir. Shamir’s extremist positions were evident in his vote on the peace treaty: he abstained. His appointment marked the end of moderation and compromise, and the autonomy talks died a painless death. In the meantime, in May 1980, Weizmann angrily resigned, saying that cuts to the defense budget put Israel at risk, and that Begin’s performance was seriously flawed. In addition to his role as prime minister, Begin assumed the defense portfolio, which he held for fourteen months.

Politically the first two years of the Begin government were marked by the peace process, from which it gained both prestige and popularity. But the economic situation was its Achilles’ heel. In October 1977 Minister of Finance Simcha Ehrlich presented a new economic plan aimed at introducing sweeping liberalization into the Israeli economy and turning it from a government-planned economy into a free one. The liberal perception was that all the malaises of the Israeli economy sprang from excessive government involvement and that market forces and private enterprise should be given free play, which would ultimately result in economic growth. Subsidies on basic goods were canceled, as were foreign currency restrictions, and for the first time the citizens of Israel were allowed to hold foreign currency and trade in it. A free-floating rate of exchange for the lira was instituted that would self-adjust according to supply and demand. For the first time people who could afford it were able to travel abroad for pleasure without paying travel tax and with no restriction on the amount of US dollars they could legally take out of the country.

Liberalization in the import of commodities should have led to price reductions, but the hope that government revenue would increase accordingly proved premature. Rising demand for consumer goods led to price hikes. Cancellation of the subsidies caused price rises in basic commodities, which hit the poorer sections of the population—the Likud’s support base. The dollar rate of exchange rose drastically, leading to price rises in imported products. Linking wages to the cost-of-living index, which was intended to compensate salaried workers for the price rises and which remained in force after liberalization, led to spiraling inflation that the Ministry of Finance had difficulty controlling. Between 1977 and 1980 the rate of inflation rose from 42.8 percent to 132.9 percent. The Ministry of Finance did not take the steps that the transition to a free market required. Government spending was not cut substantially enough. Privatization of public companies, intended to drive private enterprise, was done only on a small scale, for fear of harming the poorer sections of the population.

Begin was not well versed in economics, and he tended to accept his ministers’ complaints about the Finance Ministry’s attempts to cut their budgets. In the two years that followed the introduction of the new economic plan, his failure to back Finance Ministry policy led to an increased deficit in Israel’s balance of payments, from nine hundred million to 3.4 billion dollars. The economy was on the brink of disaster. Ehrlich resigned—the first of several finance ministers to be replaced in the Begin governments. Yigal Horowitz, who had resigned from the government because he opposed the peace treaty, now came back as minister of finance. He adopted a rigorous spending policy and had no qualms about making cuts that might hit the lower classes. But here he encountered opposition from the prime minister, who refused to cancel subsidies and stubbornly insisted on raising certain wages.

One of Horowitz’s actions was to replace the lira, whose very name recalled Israel’s Mandatory past, with the shekel, the ancient Hebrew coin that appears in the Bible. (The rate was set at ten lirot to one “old shekel.” In the second stage the rate was 1,000 old shekels to one “new shekel,” so that one new shekel equaled 10,000 lirot.) Horowitz hoped making money more scarce would arrest inflation, but it did not happen. Horowitz left the government in disgust. “The world already sees Israel as an economic cadaver,” Dayan asserted.6 In January 1981 Begin appointed his third finance minister, Yoram Aridor, who believed that his role was “to ameliorate the lot of our people.” Instead of belt-tightening and cutting government expenses, he thought he could fight inflation by loosening the reins. Removing customs duty and tax on consumer goods would lower prices and increase trade, which in turn would hopefully lead to more government revenue. An unparalleled consumer fest ensued. Middle- and lower-class families rushed to buy color TV sets, VCRS, and cars. Galloping inflation continued, and the new Israeli currency kept losing value. But the public mood changed from the gloom of frugality to enjoyment of heightened consumerism, which also increased the state’s tax revenues. Before Aridor instituted his economic policy, the Likud seemed likely to lose the election scheduled for summer 1981, but Begin now appeared to have a renewed chance of remaining in power.

Throughout 1980 and in early 1981, Begin seemed to have lost the energy needed to function as prime minister. He suffered a mild stroke and episodes of depression. Nobody dared speak publicly about the state of his health. In April 1981 the Histadrut elections were held in the wake of Aridor’s success. To everyone’s surprise the Likud emerged as a force still to be reckoned with. It gained 25 percent of the votes cast in the bastion of the left. Begin recovered overnight and began to campaign energetically. Although public meetings were now considered passé, Begin returned to the city squares and the masses and drew encouragement and energy from the displays of enthusiasm that greeted him all over the country.

Begin had no qualms about releasing the genie of ethnic hostility from the bottle and used it without a second thought as a means of political incitement. The level of incitement against the Alignment and demonization of it in this campaign, with verbal violence that sometimes spilled over into physical violence against Alignment representatives, was unprecedented. The hostile behavior of Likud supporters made it difficult for Alignment activists to hold election meetings in the development towns and city neighborhoods. The climax came at a mass rally held on election eve in Kikar Malkhei Yisrael (now Rabin Square) in Tel Aviv. After describing one movement as a “red” movement that would bring the Soviets into Israel and the terrorists into Judea and Samaria, and the other as “blue and white” and a protector of the homeland, Begin seized upon a silly remark made at an Alignment election rally held at the same place the previous evening. An entertainer had called the Likud supporters “Tshachtshachim” (a derogatory epithet for Moroccans). Coming from Begin’s lips the entertainer’s words became a symbol of the left’s derogatory attitude toward Mizrachi Jews, and he called on his followers to rouse their friends and vote Likud en masse to erase this insult to an entire section of the Israeli population. His words were received with thunderous applause in support of the Likud and hatred of the left.

A few weeks before the elections, in June 1981, the Israeli Air Force destroyed the Iraqi Osirak nuclear reactor. The decision to bomb the reactor, which at the time seemed risky and perhaps even unnecessary, was a courageous one on Begin’s part, and in retrospect few would doubt that it served the world well. During the 1977 change of government, Rabin informed Begin of intelligence reports indicating that the Iraqis were building a nuclear reactor with French assistance. Efforts to stop the reactor’s construction both diplomatically and by sabotage had been unsuccessful. In the meantime the Iran-Iraq War broke out and the Iranians attempted to bomb the reactor, causing only minor damage. Begin considered nuclear weapons in the hands of an enemy state an existential threat to Israel, which was extremely vulnerable due to its small area. In a confidential letter to Begin, opposition leader Shimon Peres, who had heard about the plan to bomb the reactor, cautioned against it. He viewed it as endangering Israel’s relations with the United States and Egypt.

Begin was aware of the risks of attacking the reactor, but contended that the predicted risk to Israel if it did not attack was far greater. He feared that if the Alignment won the elections, the reactor would remain standing. The decision to attack it was not an easy one, and there were differences of opinion within the Israeli defense establishment. There was also no guarantee that the operation would be successful. In the end the operation did succeed, with no losses. In response the United States delayed the supply of warplanes to Israel, but apart from that relations were not impaired. Sadat, who had been updated by the Israeli ambassador on the operation and Begin’s reasons for it, treated it leniently. Nothing succeeds like success, and Saddam Hussein’s brutal regime was not well liked in the Middle East. Peres accused Begin of using the attack on the Iraqi reactor as a form of electioneering. Begin responded by revealing Peres’s confidential letter and attacking him. Begin did not destroy the reactor in order to get elected, but afterward he used the operation’s success as an additional weapon in his election arsenal.

BEGIN’S SECOND TERM: THE LEBANON WAR AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF ISRAELI SOCIETY

The elections held at the end of June 1981 were close. The Likud retained a oneseat advantage (48–47), enabling Begin to present a government backed by 61 Knesset members (out of a total of 120). This slender victory was evidence that the 1977 about-turn had not been a chance event, but reflected a profound political and social change. Aryeh Naor, secretary of Begin’s first government, analyzed the results thus: “Israel’s new world of symbols based on the heritage of religion and faith is rooted in the new generation of the state. The secular world-view and the Alignment’s ideas of territorial compromise are alien to this generation, a large part of which grew up in the reality of Greater Israel.”7

Begin’s first term in office ended on a positive note. The peace treaty with Egypt cloaked Begin in the mantle of the man of peace, the resolute leader capable of making difficult decisions. The bombing of the Iraqi reactor added further proof of his leadership ability and resolve. To his supporters the expansion of the settlement enterprise was an additional success. Another in his government’s list of achievements was a neighborhood rehabilitation project. Before the 1977 elections Begin had promised that if elected he would take action to rehabilitate Israel’s deprived neighborhoods. This project was funded not by the state budget but by donations from Diaspora Jewry. Begin’s appeal to Jewish communities throughout the world to help defeat poverty in Israel was well received. Instead of turning the project and its funds over to the usual groups, such as the Jewish Agency, direct contact was established between the donors and the neighborhood or development town that would receive the funds. Involving Diaspora Jews in the project helped strengthen ties between the major donors and the Israeli right, but apart from that this enterprise was important in renewing solidarity between the Diaspora communities and Israel and bringing the Ashkenazi donors and the Mizrachi residents of the neighborhoods closer. The neighborhood rehabilitation project focused on raising the standard of housing and reducing overcrowding. Efforts were also made to enhance the aesthetic aspect of the neighborhoods and build playgrounds and gardens. In many cases the improvement in the environment caused increased awareness among residents, reinforcing their interest and involvement in caring for their neighborhood. From every point of view this was a worthy enterprise.

On the debit side of Begin’s first term was the deterioration of the economic situation. The heroic attempt to shift from a government-directed economy to a liberal one in a single leap, without a safety net and the necessary related measures, led the Israeli economy to the edge of the abyss and undermined the country’s stability.

The 1981 elections and the composition of the new government reflect the shift from a right-wing government, whose leader sought to be remembered in history as the man who brought peace to Israel, to an extreme right-wing government, whose leader now began to actualize the old worldview he had held before coming to power. The first government included Dayan, Weizmann, and Yadin, who among themselves and with Begin constituted a system of checks and balances. In his second government Begin, whose health was failing, lacked these moderating forces. Ariel Sharon—the man Begin had earlier been reluctant to put at the head of the security establishment—was appointed minister of defense, and Yitzhak Shamir, a dyed-in-the-wool rightist, became foreign minister. The chief of the General Staff was Rafael (Raful) Eitan, who accepted Sharon’s authority. It was a lusterless government without heavyweight figures who could push back against Sharon’s influence. Nor were there other military men in the government who could serve as a counterweight. (Minister of Communications Mordechai Zippori came from the military, had served as deputy defense minister in the previous government, and had tried to rein in Sharon, but he did not have equal status in Begin’s eyes with the illustrious General Sharon.) The external political arena had also changed. Sadat was assassinated on October 6, 1981, and President Reagan replaced President Carter. If Begin’s first term was marked by peace, his second would be marked by war.

As we have seen, after the civil war in Lebanon the PLO and its fighters had relocated to south Lebanon. Israel would retaliate against terror attacks on Israelis by attacking the PLO, who retaliated in turn with Katyusha rocket attacks on the northern border settlements. IDF ground operations against the terrorists brought short-term quiet to the area. Since the mid-1970s Israel had been fostering a Christian militia, the South Lebanon Army (SLA), in south Lebanon, which helped hold the PLO in check. In Lebanon relations deteriorated between the Syrians and the Christians, especially the Phalangists, led by the Gemayel family. The Christians sought Israeli aid against the Palestinians in Lebanon, who together with the radical pro-Syrian left tipped the scales in Lebanon’s ethnic and religious conflicts against the Christians. As prime minister, Rabin had vigorously refused to be drawn into military action to aid the Christians; the same stance guided Weizmann when he was minister of defense. But when Begin became minister of defense, he decided to aid the Christians—not just indirectly by supplying military equipment but also with direct military action. Begin reasoned that Israel could not allow a minority to be annihilated by a violent majority. But the Christians were not a helpless minority, and certainly not paragons of virtue. Begin’s ostensibly moral rationale for Israel’s initial military involvement in the Lebanese civil war was aimed at influencing President Reagan, but Reagan was unimpressed. Begin’s and Sharon’s ally in the American administration was Secretary of State Alexander Haig; Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger had serious reservations about the Israelis’ saber rattling.

Begin and Sharon, who wanted to ensure Israeli control over Judea and Samaria, believed that weakening the PLO in Lebanon, and perhaps even removing its headquarters from the country, would likely also weaken the Palestinians and force them into a formula for autonomy that would guarantee an Israeli presence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip for generations. In the meantime Israel’s security elite reinforced its ties with the Christians, who sought to draw Israel into a war in Lebanon by leading the Israelis to believe that they would be directly involved in the fighting themselves. Opinion was divided in the Israeli security establishment regarding the Christians’ trustworthiness. Would they indeed play their part in an Israeli attack and drive the Palestinians out of Beirut? The Christian leadership, including Bashir Gemayel (who unlike his pro-Syrian brother Amin was considered pro-Israeli), did not conceal its reservations about an open alliance with Israel. Even as Israeli military aid flowed into the Christian-held ports in northern Lebanon, these leaders refused to publicly support a partnership with Israel. Even more to the point, they did not want to appear to be fighting at Israel’s side. They saw themselves as part of the Arab world, and in the way of Lebanese Christians from time immemorial, they maneuvered between the rival camps, with their primary commitment being to themselves.

Two plans for military action were formulated: “Big Pines,” which envisioned the possibility of occupying a large part of Lebanon, reaching the Beirut–Damascus road, and joining up with the Christians; and “Little Pines,” which involved occupying a forty-kilometer-deep buffer zone in south Lebanon—that was the range of the rockets deployed by the PLO at the time. Following a massive bombardment of the Galilee panhandle settlements, especially Kiryat Shmona, in the summer of 1981, which led large numbers of residents to evacuate their town, an American-mediated agreement was reached to ensure quiet along the northern border. Begin and Sharon then began looking for an excuse for an attack in Lebanon that would alter the balance of power. The attempt to obtain government approval for Operation Big Pines failed; Begin remained silent, while Sharon was unable to enlist a massive majority for an all-out war. Sharon realized that in order to get approval, he would have to present the smaller-scale plan. But he concealed his intention to expand that plan in the course of the fighting. The IDF high command was alerted in advance that the plan might be expanded and told to prepare the forces for a “rolling” stage-by-stage operation. Then an assassination attempt on the Israeli ambassador in London by a member of the Abu Nidal organization provided Begin and Sharon with their rationale. The head of the General Security Service tried in vain to explain to the cabinet that Abu Nidal belonged to a breakaway branch of the PLO and did not represent PLO policy. The prime minister cut him short, insisting that this terrorist outrage justified going to war against the PLO.

This was a war Begin had wanted for a long time. “The alternative to this operation is Treblinka, and we have resolved that there will be no more Treblinkas,” he asserted dramatically on June 5, 1982.8 In a lecture delivered in August 1982 at the College of National Security, he spoke in favor of “a war of choice.” In Begin’s assessment all Israel’s wars, except for the 1948 war, the War of Attrition, and the 1973 war, had been wars of choice. According to him, every preventive or preemptive strike, or even a war resulting from the crossing of redlines, was a war of choice. With this rationale he put the Lebanon War in the same category as not only the Sinai Campaign—though Ben-Gurion had undertaken it out of fear of Egypt’s intensified armament and then withdrawn as soon as he saw the reaction of the two superpowers—but also the Six-Day War, which all Israelis saw as a war initiated by Egypt. In this expanded definition of the term war of choice, Begin sought legitimacy for going to war in Lebanon. He justified a war of choice by saying it obviated a war of no choice later. “There is no moral diktat that a nation must, or is entitled to, fight only when its back is to the sea or it is on the brink of the abyss.”9 This concept contradicted a very basic ethos in Israeli society: the defensive ethos, which shaped the worldview of generations of fighters in the Yishuv and the state. For that ethos war must always be a war of necessity, in which the nation stands on the brink. In the end neither Israeli society nor the IDF accepted Begin’s redefinition of this ethos.

To what extent Begin subscribed to Sharon’s concept of a stage-by-stage rolling war is a bone of contention between Begin’s admirers and critics. What is certain is that Begin gave Sharon’s actions his approval, sometimes before an action and on other occasions afterward. When the IDF invaded Lebanon, Begin was convinced the operation would last only a couple of days and cause few casualties. He was not familiar with either maps or military actions. For example, like other members of his government without a military background, he believed Sharon’s prediction that outflanking the Syrian forces in the Bekaa Valley would force them to retreat and not clash with the IDF. But all the IDF officers who saw the plan realized that they were going to war with the Syrians. Sharon explained to Begin and his cabinet members that expanding the war from forty kilometers from the border to Beirut, and from clashes with Palestinians to attacking the Syrians, was necessary to protect IDF troops and avoid losses. Foreign journalists who interviewed Begin during the fighting found it hard to decide whether he was a liar or simply incompetent, for he did not know what was happening on the battlefield. After all his denials, which were based on Sharon’s misleading reports, the individual who informed Begin that the IDF was already in Beirut was American mediator Philip Habib.

The war gradually expanded. Instead of being a limited battle with the Palestinian organizations, it became a large-scale war that included fierce armored battles against the Syrians, taking out the Syrian ground-to-air missile array in Lebanon, and bitter fighting in the Sidon refugee camps and later the Beirut camps. The IDF’s entry into West Beirut following a two-month siege of the city was intended to exert pressure on Arafat to take his headquarters and fighters out of Lebanon. In the meantime the Palestinian civilian population of West Beirut suffered as a result of heavy bombing and disruption of electricity and water supply until the PLO and the Syrian forces inside the city agreed to evacuate it in August 1982.

In presenting the operation to the government, Sharon had estimated there would be a few dozen Israeli casualties, in complete contradiction of the much higher estimate made by IDF officers, whose view was not brought before the government. The war exacted close to five hundred Israeli casualties by the time just before the PLO evacuated Beirut. This was the first IDF entry into an Arab capital, and it was accomplished almost clandestinely, without the government discussing it.

This was the first time the IDF went to war not to thwart a security threat, but to bring about a new political order in the Middle East through unlimited use of Israel’s military might. Sharon’s plan was that Bashir Gemayel would be elected president of Lebanon under cover of Israeli tanks, and then Lebanon would be the second Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel. The Syrians would be forced to withdraw from the country, and the Palestinians would have to evacuate to Jordan in large numbers. Sharon’s dream was that Jordan would become Palestine, leaving the entire west bank of the River Jordan in the hands of the Jews. Begin shared this dream, which is apparently why he continued to back Sharon, even though his cabinet colleagues rebelled against Sharon’s use of unlimited force, carried out without government approval. When Begin met with Bashir Gemayel in Nahariya during the ceasefire on September 1, 1982, he realized to his chagrin that Gemayel had no intention of changing his relations with Israel from a secret liaison into a legal marriage, and that he would neither make peace with Israel nor openly cooperate with it. The Syrians stated that they had no intention of leaving Lebanon. When Bashir Gemayel was assassinated on September 15, 1982, the IDF entered West Beirut to prevent acts of vengeance, but gave the Phalangists permission to enter the refugee camps. The Phalangists avenged Bashir’s death with a massacre in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. Hundreds of innocent Palestinians were killed. Although the Israelis were not directly involved in the massacre, the fact that they were in charge made them responsible for the inhabitants’ safety—and they never assumed this responsibility. The massacre aroused a furor in Israel and around the world, and opposition to the war reached new heights (discussed later).

After August 1982 the IDF had no real mission in Lebanon, but a way of withdrawing from it that would preserve the forty-kilometer buffer zone in south Lebanon after the retreat could not be found. The longer the IDF remained in Lebanon, the deeper it sank into what came to be called “the Lebanese mire.” The wars between ethnic and religious groups in Lebanon did not stop. As an army of occupation the IDF came into close contact with the local population and aroused hostility among various groups. When the IDF invaded Lebanon its columns had been greeted by joyous crowds throwing rice in welcome. Now the troops became sitting ducks for terror attacks and incessant sniper fire. A war that was supposed to last only a few days had become protracted and resulted in heavy losses. Although the PLO had vacated Beirut and south Lebanon, the organization was not broken and its headquarters, now in Tunis, continued to be the political entity representing the Palestinians. While the Syrians had been dealt a heavy blow, they proved themselves a worthy adversary of the IDF. They did not withdraw and remained leading players in the Lebanese theater.

The war in Lebanon, especially the bombing of Beirut, provoked tremendous opposition in Israel and throughout the world, and heightened awareness of the Palestinians’ plight. After the war President Reagan demanded that Israel withdraw from the West Bank and that it be returned to Jordan—an issue that had not previously interested him. If Begin and Sharon had hoped the war would strengthen Israel’s position in the occupied territories, what transpired was the opposite. The draft peace treaty agreed upon by Israel and Amin Gemayel, who was elected president of Lebanon in May 1983, was thwarted by the Syrians. The draft was clearly not worth the paper it was written on. And it was evident that Sharon’s strategic concept never had a leg to stand on. As in the past, Israel could win the war but was incapable of imposing peace.

In September 1983 the IDF began a gradual withdrawal from Lebanon, with local guerilla forces snapping at its heels. Amal, the moderate Shiʿite militia that had been weakened in the war, was now replaced by Hezbollah, a radical Shiʿite militia whose objective was not only to drive the IDF out of Lebanon but also, with Iranian support, to fight Israel incessantly. The IDF withdrawal from Lebanon continued until June 1985, when the force deployed along the international border while continuing to control a narrow buffer zone on the Lebanese side, where the Christian-commanded SLA operated, helping maintain security along the border. Six hundred seventy Israeli soldiers were killed during the war, and between 1982 and 2000 (when the IDF made its final withdrawal to the international border), a total of 1,216 soldiers were killed in Lebanon. Close to 18,000 Arabs were killed in the Lebanon War, of whom at least 10,000 were Syrian troops and Palestinian fighters.

The Lebanon War was a watershed in the history of Israeli society. It was the first war to be prosecuted without a consensus. In the first stage of the fighting, both the public and the media thought the campaign was similar to the 1978 Litani Operation, which had been launched as a reprisal for a terrorist outrage perpetrated on Israel’s coastal road. The IDF had crossed the border into Lebanon, carried out a punitive action, and returned to Israel. The thinking this time included the possible establishment of a buffer zone to prevent Katyusha rocket attacks on the northern settlements. As initially presented to the public, the operation had almost wall-to-wall support. Once it emerged that the operation was exceeding its predetermined limits, public and military support eroded. The right was infuriated by criticism of the war in the media. It contended that a government at war should not be criticized, on the model of Begin’s own restraint when he was in the opposition. A celebrated article published at the time was titled “Quiet, There’s Shooting.”

The problem was that until that time, the governments of Israel had been to the left of the opposition, which was militant—always willing to support military operations, but not withdrawals. This time the shoe was on the other foot; the government was to the right of the opposition and went to war without speaking openly and honestly to the opposition about its objectives. As the war progressed, a mutual feedback loop of information and reaction developed between the army and civilians. Armored brigade commander Colonel Eli Geva resigned his command and refused to take part in the assault on Beirut—the first time in the history of Israel’s wars that a senior officer refused to obey orders. Geva’s action reflected the frustration and unease pervading the army. The troops felt they were fighting for objectives far beyond what was necessary to defend Israel. Soldiers reacted bitterly: “People definitely feel that they gave life and limb not in the defense of Israel, but for a whim.”10 They also felt that there had been manipulation of the media by the government; what was being reported to the public was not what they were seeing on the ground. By the same token what the public saw on their TV screens at home and in the international media did not jibe with what the commanders were saying.