18 | CHEATING DEATH

In the 21st-century world of Silicon Valley, not many people had heard of Benjamin Gompertz, and there was a good reason for it. Born in the 17th century, he was a little known, self-taught mathematician. Because he was a British Jew, he had been barred from a university education, so he took up work at the London Stock Exchange. In his spare time, though, he absorbed all the writings of Isaac Newton and mastered every kind of advanced mathematics. When a couple of his close relatives founded the Alliance Assurance Company in 1824, Gompertz became its head actuary.

Insurance companies like to know when, as a group, people die, and the central duty of an actuary is to figure that out. And that was how the young math whiz came up with an equation known as Gompertz’s Law of Mortality. It provided a mathematical indication of when people are most likely to depart the planet.

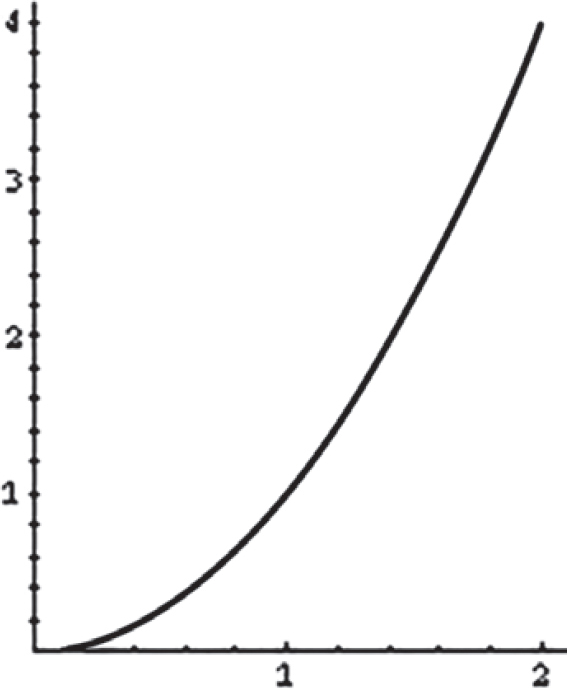

Art Levinson found this equation fascinating. When he talked about it at Calico, he would leap to the whiteboard to write it out and then rapidly plot its graph, also known as the Gompertz curve. When expressed, it looked a little like the bottom end of a steep ski slope.

To most people, the equation didn’t make a lot of sense. It read: H(t)=αeßt+λ.12 But to Levinson it was a beautiful thing. He admired its clarity and logic. To take something as powerful and emotionally complex as living and dying and express it in a simple scientific formula—well, that was perfection!

The H(t) in the formula stood for the many deadly hazards humans face over time (t). The variables on the other side of the equal sign together explained how, exactly, all of that dying happens. The really important variables in the equation were alpha, beta, and gamma—the α, ß, and λ in the equation.13

Levinson had entirely forgotten about Gompertz, until he, Botstein, Kenyon, and the rest got to talking about the mathematics of growing old. Without realizing it, Levinson had seen this same Gompertzian insight back when his uncle Howard had sent him The World Almanac. As with those statistics, the Gompertz equation revealed that during the early years of life, the beginning of the curve was pretty flat; death and danger were remote, and health was abundant. Then as the curve began to rise, it showed that each year death marched exponentially closer. The steepness of that curve said something chilling about human life span: The likelihood of dying doubled every eight and a half years! Which meant that by the time you got to 70 or 80, you were not going to last much longer.

Levinson explained the workings of the equation like this:

Alpha represented the personal, genetic hand nature dealt you—bad cards or good—together with your own experience: stress, diet, medical treatments, exercise, and economic/social status. Alpha could change from person to person depending on all of those variables. Gamma was a random, but lethal, event: a car accident, drowning, murder—the sorts of tragic occurrences that were completely random. But the third variable, beta, was universal, a force that affects all human beings regardless of their personal experience. No matter how terrific someone’s genes and upbringing are, no matter how well one handles stress or how rigorously one might work out and faithfully consume a Mediterranean diet, he or she was not going to live 200 or 300 years. No human lived that long.

Why? Because for one reason or another, evolution long ago set a universal life limit for every animal, including humans. The maximum for Homo sapiens appeared to be between 110 and 120 years. No one lived 150 or 200 years. Therefore, if you were really going to radically extend human life, it was clear someone was somehow going to have to change beta. It was the only way you could really solve the Ultimate Problem.

Levinson had come across the equation when he met Larry Norton about 25 years earlier. A physician and cancer biologist at Sloan Kettering, Norton had used the formula to describe how cancer tumors grew. Slow at first with the initial tumor, and then rapidly as tumors spread to other parts of the body. Norton’s insight forever changed the way cancer was treated with radiation and drugs. One scientist called the Gompertz curve “one of the greatest quantitative laws of biology.”

Among the traits that Levinson found particularly appealing about the equation was that it split the problem of dying into three neat pieces.

There was little anyone could do about gamma. It was impossible to change or eliminate it. As horrible as it is, people sometimes die for no good reason.

Alpha could be improved, but only up to a point; after all, science had already nearly doubled human life span over the past 115 years, at least in the world’s wealthiest nations. Continuing advancements in cancer, and a cure for Alzheimer’s, would improve alpha even more, and that would be wonderful—but it would not fundamentally change the human ability to pass beyond that maximum limit. That was why alpha was getting tougher and tougher to improve. If nothing else killed you, your chances of dying, on average, still doubled every eight and a half years. Evolution had created an upper limit, and no amount of luck or abundant alphas were ever going to improve beta.

But what if you could change beta—actually amend the inborn life span of the human species? That was a different story. Hadn’t Cynthia Kenyon found something like this with her Daf-2 discoveries? Was a solution to beta lurking there, hidden among our three billion genes, that could help the human race make the leap from 80 years past 115 to 200 or even 300, maybe more?

To explore that idea, Levinson asked one of Calico’s computational biologists, a researcher named Eugene Melamud, to run some numbers and see exactly what happened if beta could be beat.

Melamud started by reviewing a sample of 100,000 Americans. The statistics showed that by age 50, fewer than 5,000 of those people die: almost 50 percent from poisoning, 18 percent from accidents and other killers. Heart disease dispatched hardly more than 6 percent!

But remember, the average human’s chance of dying doubles every eight and a half years, and so after age 50 the decline gathers speed, despite all the beta-blockers and cancer drugs we have thus far applied to our afflictions. By age 60, the number of the deceased reaches 11,000, and by age 72, 25,000 have passed through the veil. At age 100, fewer than 3 percent of those 100,000 will still be living. Melamud’s graphs showed that the longer people lived, the longer the list of diseases became: malfunctioning hearts, cancer, and Alzheimer’s being the three biggest killers. Whatever slowed those diseases and increased life span occurred thanks only to alpha’s whack-a-mole–style medicine.

For fun, Melamud changed the statistical model for beta—the constant 8.5-year number that set the evolutionary life limit for humans at no more than 120 years. When that number was zeroed out, the calculations didn’t merely show an improvement; they blew everybody away. If the increase in beta was halted at age 30—a huge if to be sure—the median life span of that person would leap to 695 years! That was just the median. Some people might live nearly 1,400 years. If you stopped the clock at age 50, the number dropped to 181 years, still more than twice the average.

Levinson even asked Melamud to run the formula if beta were frozen at age 10, the safest of all ages. The math stunned him: The expected life span for 10-year-olds sans beta was 7,987 years, with 90 percent of them living almost 30,000 years! With beta at zero from age 10, a child’s genes were so squeaky clean that almost nothing could kill them. The aging clock would stop, and they would simply continue to repair themselves, pretty much indefinitely.

Of course, this would require accomplishing something that, up until now, only the great gears and wheels of evolution itself had accomplished: resetting life span at the most profound genetic and molecular level. But Levinson’s point was, beta was powerful! If you wanted to get a really big bang for your time and energy, that was where the magic would be. And if it were accomplished, it would represent the greatest scientific and historic leap in all of human experience. Was it possible?