Michael Ayrton

A Memoir

This memoir appeared in the June 1976 issue of Encounter

‘Why’, said the Editor of this journal, ‘was he so eclectic?’ ‘Because’, said the writer of this article, faced over a dinner table a few days after Michael Ayrton’s death with the need to produce an instant answer, ‘he was not educated.’ A typical dinner-table exchange? Glib, superficial? Yes, possibly, even probably, but not, I think, certainly. As Ayrton’s fellow member of the Brains Trust, Professor Joad, might have put it, it depends what you mean by eclectic and in particular whether that word is used pejoratively; and if eclecticism in the pursuit of originality is no vice, education in the pursuit of learned conventionality is no virtue.

Had Michael Ayrton, the son of a fiercely feminist socialist mother, Barbara Ayrton, and the mildly ineffectual but amiable socialist literary critic Gerald Gould, been fully educated within even the most enlightened sectors of the English system, he would assuredly have been a duller, less original and far less talented man. Fortunately, at the age of 14, he incurred the unfavourable notice of the headmaster of his boarding school who summoned Gerald Gould in a phraseology which caused that worthy man to fear the worst and prepare for yet another pale, rather shameful little episode of the kind of which countless autobiographical sketches and, God help us, whole English novels have been made. When told that young Ayrton had indulged in neither mutual masturbation nor buggery, but had actually slept with a girl, his father was so relieved, not to say delighted, that he removed his son with pleased alacrity. Thus from the age of 14 onwards Michael wandered abroad and became first a teenage autodidact, and then a youthful prodigy, and then a mature and brilliant artist.

Painter - sculptor - draughtsman - engraver - portraitist - stage designer - book illustrator - novelist - short-story writer - essayist - critic - art historian - broadcaster - film-maker. There were probably other artistic functions, but, in the fifteen or so years that I knew him, those were the facets of his work I came to know and admire. As a person he also had prodigious gifts as a clubman, a wit, a conversationalist and a friend. He hated cricket and scorned any organised conviviality. But put him at one of the large tables at the Savile Club, or at the head of his own table in that glorious, totally Ayrton-stamped, 13th-century house in Essex where his wife Elisabeth, a notable expert on English cooking, kept their guests in a state of permanent gluttony, and you had a magnetic and irresistible personality.

If ever a man needed a Boswell, it was Ayrton (and if ever a man would have loathed the very idea, it was he). He was a supreme raconteur and anecdotalist, each story honed and polished for maximum suspense, joy, and amusement, but the stories were impoverished without that mellifluous, ironic voice. Like most substantial artists, he was an egotist; and he liked to converse because he liked to argue, and to learn, and was in fact omnivorous for knowledge, craving the didacticism of his peers in other fields. He loved to shine in company, and could shine anywhere; but, as any student of English society and culture knows, the greatest crime is to be too clever by half. It’s all part of a British aberration, fostered perhaps by the dottier followers of the wretched Dr Arnold, that you must never be seen to be trying: if you really are brighter than the other fellow you’d better not show it and if you want to get ahead, keep your talent under your hat for as long as you possibly can.

The wit and wisdom of Michael Ayrton were, I think, among the chief reasons for his lack of true recognition. They were too public, too flamboyant. A man who can perform in front of a television camera with greater skill and professionalism than those who are supposed to sit in judgment over him is not likely to be popular. A man who writes better about aesthetic matters than those whose principal livelihood it is to do just that tends to garner not wholly favourable notices. One of my bonds with Michael was the distrust of most critics, particularly those who wrote exclusively about art, and his undisguised scorn did him little good with opinion-makers. For Michael, criticism, like patriotism, was not enough. As an art critic, I survived with him because the act of criticism occupied a proper place in my scheme of things. For several years I was a regular reviewer and, apart from looking at pictures, which was what one did anyway, the copy was written between lunch and dinner on Sunday and dropped into the editor’s office on Monday morning. It never interfered with being a director of a large publishing-house which Michael, having been art critic of the Spectator, perfectly appreciated. He would never accept that a few hundred words a week was a sufficient task for a man; he knew how it was done, and it was too easy by half.

There is a clue in Michael’s relationship to criticism to the relationship of critics to him. He thought their work essentially simple if not actually nugatory, and he rarely bothered to hide this. At the same time, because his mind moved fast and he always wanted to find something new to do, he rarely gave critics any carefully programmed development to latch on to; so that even if he had not alienated them with his scorn, he offended them with, in their terms, an ever-increasing inconsistency.

Thus one had the spectacle of a boy-wonder becoming a prophet without honour, all in the space of one generation. The obvious explanation is, of course, the excessive versatility. But if versatility is normally a virtue, why, in Ayrton’s case, should it be a misdemeanour, as it evidently was? (The old English tag, about cobblers and lasts?) Versatility in the visual arts alone would probably have been quite acceptable, indeed encouraged; it was all those other activities that got a bit much. The young Ayrton, having parlayed his expulsion from school into a precocious European grand tour, began his artistic career with a show at the Leicester Galleries in 1942 when he was only 21; and in the same year he collaborated with John Minton in the stage designs for John Gielgud’s Macbeth. This wasn’t a bad start for someone with no formal art training. In the late 40s he painted in Wales with Graham Sutherland, to whom a splendid Ayrton landscape once belonged. Critics like Bryan Robertson regarded Ayrton, together with near-contemporaries like Minton and Sutherland, as among the great white hopes of English painting in the 40s and early 50s. Robertson bestowed on Ayrton what used to be one of the accolades of the English art scene, a Whitechapel retrospective, as early as 1955.

It was an auspicious beginning, but one from which, critically speaking, he never looked forward. Gradually, as he changed dealers (and then, for some years, did without dealers at all), as his work grew and varied and metamorphosed, so his reputation among his friends and admirers expanded and consolidated and his reputation in the world of the visual arts, the world that most mattered to him, dwindled.

He had the temerity to become a man of many media and always with that consummate verbal fluency, that total articulateness which so often left not less intelligent but simply less verbally gifted people floundering. There are still those who prefer their artist types to be incoherent unless they have a brush in their hand.

When I first met Michael Ayrton - we were fellow judges of an appalling painting competition in a small provincial town - we spent our modest fee, a fiver apiece in cash, in the nearest pub on substantial quantities of whisky and, within the hour, were fighting each other for the truest stranglehold on the great Hector Berlioz. Later he was to give me a copy of his book Berlioz: A Singular Obsession inscribed simply: ‘For Tom, a fellow obsessionist, from Michael, 1969.’ The year was the centenary of the composer’s death. I brought that arch-Berliozian, David Cairns, the superlative translator of the Memoirs, and Ayrton together at my dinner table and watched them trade ever more recondite and arcane minutiae. Michael introduced me to La Mort de Cléopâtre and that seductive noise reverberated repeatedly through the Ayrton household at Bradfields (you can’t play Berlioz pianissimo, even at three in the morning). On the wall was an oil of Hector which Michael had painted with those gimmicky eyes that appear to follow you around the room. I once told him of a rare full-scale staging of The Damnation of Faust in which the set was substantially inspired by Piranesi’s Carceri, for Michael one of the greatest sequences of engravings in the Western world, and it was a perfect ‘Ayrtonian’ consummation. In a dazzling short story he created (or, as he would have put it, recreated) in ‘An Episode in the Life of a Gambler’, an encounter between Berlioz and the condemned poet, gambler, and murderer Pierre Lacenaire, a brief work of considerable deductive scholarship and macabre wit. The Berlioz theme is, in fact, central to any understanding of Michael because it crystallised so many facets of his life and work; the informed passion for music; the great appeal of the Romantic Movement in which his admiration for Piranesi and his influence on the Romantic imagination figured so largely; the worship of the underrated Ingres, whose drawings Michael saw as one of the high points of 19th-century art - in fact, a plural obsession with the giants of that century. His homage took the form of drawings, paintings, bronzes, and also a remarkable BBC Television programme to celebrate the centenary of Berlioz’s death. As Ayrton himself wrote, it was ‘the realisation of the private dream of a far from fashionable sculptor and painter about the personality and the music of a composer and writer who is only now becoming fashionable a century after his death...’

I suspect that Michael in his later years, if one can speak of the later years of a man wantonly removed at 54, identified more and more with Berlioz, not with the habitual paranoia of the artist (he knows he’s a genius, but the world’s against him) but with the sense of being so unrecognised and under-rewarded as to feel himself to be an outsider. Berlioz was indeed a Protean outsider, and Ayrton felt himself to be much the same. In a way the association was beneficial because intellectually stimulating; in another, it induced in him a blind spot about the painted results of his singular obsession which, at a crucial stage in his career, adversely affected a major commercial opportunity.

One of his earlier idols was Wyndham Lewis. When the National Book League launched an enterprising series of exhibitions entitled Word and Image devoted to the more interesting British writer/painters of our time, it was appropriate not only that they should start with Lewis and Ayrton but also that they should be shown jointly. I wrote the catalogue introduction, and I was struck by one passage from Ayrton’s brief memoir of Lewis, ‘The Enemy as Friend’ (it can be found in Ayrton’s last and best collection of essays, The Rudiments of Paradise):

in the Redfern Gallery, during his 1949 show... I wandered in to find two silent figures contemplating the exhibits. One of these was Mr T. S. Eliot, dressed with quiet elegance in a blue business suit, stooped like a benevolent osprey and gazing intently at Lewis’s early self-portrait. This imposing picture shows the artist gazing stonily out from the canvas and wearing a large, fierce hat. The sole other occupant of the room was Mr Lewis himself, wearing a large, fierce hat and gazing stonily at his own portrait of Mr Eliot, a picture in which the poet is dressed with quiet elegance in a blue business suit...

Ayrton always had a high sense of the absurd; but he also was an exceptionally kind man and went on to record how, when Lewis was blind and luxuries rare, Eliot used to send him champagne (which, together with caviare and walnut cake, evidently comprised his chief solace in his declining years). Wyndham Lewis had once had, to say the least, unfortunate right-wing and anti-Semitic tendencies which he shared with other pillars of the Modern Movement as part of the strange English cultural heritage which believed in the rightness of the Right and the wrongness of the Jews. To Michael, with Zangwill blood in his veins, and with a passionate commitment to a non-Communist, neo-Orwellian Left, nothing could have been more anathematic.

Yet, as is well known, Lewis had recanted, and the friendship between them was such that, for a time, Ayrton was Lewis’s visual amanuensis, designing Lewis’s book jackets, and letting the great blind man choose and, where necessary, describe the alterations he wanted made. In retrospect, Lewis and Ayrton were soul-mates, both hating ‘the Enemy’, with a violent iconoclasm, switching with ease from pen to brush. Both had superb critical gifts; both saw draughtsmanship as the true beginning of painting; both, by their differing physical afflictions, were hampered in the realisation of a prolific output (although both left, nonetheless, a prodigious amount of material). Both wielded a dreadful scourge when faced with cant, pretension, pomposity or hypocrisy. Both, more than anyone else this century, tried to record faces for our intellectual posterity, Lewis usually with large-scale oils, Ayrton usually with drawings. Significantly, one of Ayrton’s relatively few oil portraits, and perhaps the best formal portrait he painted, was of Wyndham Lewis in 1955 shortly before his death. Ayrton and his wife came to offer condolences to Mrs Lewis, and found that workmen had already arrived to tear down the building. In a frenzy they managed to rescue, from a laundry basket, the contents of the disused studio. As Ayrton wrote, ‘Among those we rescued was a large pencil drawing of Ezra Pound, with half the head torn away. This half head, in due time, I replaced. It was my last act as a sort of substitute for the eyes of Wyndham Lewis...’ With much of Lewis’s angularity, but with his own, spiky, idiosyncratic draughtsmanship, he gave us, with an occasional virtuoso oil such as that of Constant Lambert, superb drawings of Dylan Thomas, Henry Moore, William Golding, Norman Douglas, William Walton, Christopher Isherwood, and many more. Michael was not a formal portraitist in the sense that people paid him; he simply painted or drew those whose personalities or faces particularly interested him (and, preferably, who were friends). As with Lewis, a considerable section of English cultural life, and a characteristically eclectic one at that, will be known, where the camera is not considered enough, by his portraits.

Ayrton combined, to an unusual degree in an artist, generosity for others and an inability to hide his sense of injustice at the lack of recognition of himself and the excess of it, in his view, received by others. For those, such as Moore or Giacometti, whom he idolised and loved, his praise could not be too great. About those of his contemporaries and near-contemporaries with their Tate and Hayward retrospectives and their decorations, he was, often with justice, scathing. Was he jealous of their greater recognition? He simply felt that he had been neglected. An honorary doctorate from Exeter University was slim pickings for three full decades in the public eye. This is not to suggest that he felt superior to his contemporaries; he just knew enough to know what they had done, and how yet, typically, in his own collection he had a not inconsiderable selection of works by his contemporaries.

He stimulated, when I was at Thames & Hudson, the definitive book on Wyndham Lewis’s art, and caused me to rescue from oblivion, at Secker & Warburg, Lewis’s savage satire of the world of Arnold Bennett and Desmond McCarthy, The Roaring Queen. His political passions prompted the publication of the first solid and full-length book on the Colonels and why they were doomed to fail, Greece under Military Rule.

As a critic Ayrton was primarily constructive, and revelled in the opportunity of sharing a discovery; and here, again, his eclecticism, springing from his lack of formal education, was valuable. Had he progressed from, say, Cambridge to the Courtauld he would doubtless have published learned articles in scholarly journals which would, inevitably, have been read only by other scholars. As it was, he wrote his articles, gave his lectures, made his broadcasts on a great variety of topics to as wide an audience as possible. In his essay ‘The Terrible Survivor‘in which there is a learned account of Barna di Siena he wrote: ‘I am not a scholar but rather a celebrant’, and it’s a fine distinction. For a total understanding of Piero della Francesca one has recourse to the work of the art historians. But if one wants an insight into the effect upon the viewer of a key work by that Umbrian genius and of his exact placing in that still timeless world, one must read Ayrton’s short, intense, utterly personal and convincing essay on his own discovery of Piero’s La Madonna del Parto in the tiny little hill-town of Monterchi. It was in that spirit also that he made his one full-scale art-historical effort, a monograph, the first and most comprehensive (including a catalogue raisonné) in English on Giovanni Pisano. Aided by the enthusiasm of Henry Moore, out of whom he conjured an introduction, Ayrton brought this relatively little- known genius to the attention of a far wider public in a subtly written and comprehensive work. It is a loss to art history that he never had time to write his projected monumental survey of the art and practice of bronze sculpture.

But he could also be non-celebratory. He could also, bravely, change his mind, and it is illuminating to read, in rapid succession, his essays on Picasso (all available in The Rudiments of Paradise, that most eclectic of all collections) entitled ‘The Master of Pastiche’, ‘A Reply to Myself’ and ‘The Midas Minotaur’.

The three essays span the three decades of Ayrton’s perceptions and preoccupations. In the first, dated 1944, Ayrton questioned Picasso’s at that time unquestioned eminence and concluded that: ‘The whole body of Picasso’s work amounts in my opinion to a vast series of brilliant paraphrases based on the history of art.’ Ayrton in 1956 mildly retracted some of his strictures but re-emphasised others ; drew a parallel, in terms of repute, between Picasso and Liszt; and emphasised the talent but drew the line at the genius. ‘The Midas Minotaur’, published in 1970, refers in detail, and with some sympathy but by no means uncritically, to John Berger’s Penguin study, The Success and Failure of Picasso, a book which Ayrton had himself been asked to write. In declining, he had suggested Berger as a substitute, and Berger, in the first serious, long analysis of Picasso as less than a titanic and universal genius, inscribed the copy he sent Ayrton to that effect and wrote to Ayrton that he believed Michael to be ‘a prophetic exception’ to the worldwide chorus of adulation.

‘The Midas Minotaur’ is almost a paradigm of the relationship of Ayrton to Picasso, of Picasso to the Minotaur, of the Minotaur to Ayrton, and of Picasso to King Midas. Ayrton’s analysis probes the themes of vigour and weakness, impotence and old age, fame and its curses, asses’ ears and irony, and it looks forward to his last prose work, his novel, The Midas Consequence. The hero of The Midas Consequence, a novel published in 1974 to a strange mixture of derision, hatred, puzzled respect and wary admiration, is a very old and fabulously wealthy artist called Capisco. The anagramatically inclined inevitably identified him with Picasso, but this was facile. Capisco did, of course, have much of Picasso; but, with a nice mixture of eclecticism and egotism, Ayrton had in fact created an artist-hero who contained fragments of Matisse, de Chirico, Henry Moore and himself. He was also, since the author was not exactly a man short of inventive powers, a character in fiction, who performs properly invented acts in a book of great ingenuity, using a number of cinematic techniques and devices in a novel whose very framework is the making of a documentary about the artist hero. (The book, incidentally, is dedicated as an act of both friendship and homage to that great documentary film-maker Basil Wright, with whom the ever versatile Ayrton made a film on Leonardo drawings and another on Greek sculpture.)

If, in retrospect, The Midas Consequence is a less satisfactory novel than its predecessor, The Maze Maker, I suspect the reason is to be found in Ayrton’s preoccupation with myth. In The Midas Consequence he dealt with modern myth which is no more than fame (and fame in the end, like Capisco’s fabulous wealth, is transitory) while ancient myth is, perhaps by definition, sufficiently everlasting and permanent and could bear more readily the full weight of Ayrton’s erudite inventiveness. To a contemporary artist like Ayrton the modern titans like Picasso or Moore appeared not so much Minotaurs as minatory. They dare not be imitated, and one runs mortal risks if one comes too close. The genuine mythology of the Classical past is safer and, because more complex, more rewarding. Both Picasso and Ayrton made modern Minotaurs, and I cannot help thinking that is why The Maze Maker, which deals, among other things, with the origin of the legendary Minotaur, is a more powerful book, and the identification of author and protagonist/narrator is total:

My name is Daedalus and I am a technician. This I chose to be. I have made many things in many places and done so cunningly, for that is the meaning of my name. I have constructed buildings and planned fortifications. I am proficient in stone-carving and I can make the forms of Gods in wood, competently joined. I have made many tools to do these things and invented others to make the work simpler and have it better done. Also I can paint images and I am adept at mechanical contrivance. All these things I can do as well as any other, be he who he may...

‘The archetypal Maker’, in William Golding’s phrase, threads the nautilus, constructs the artificial cow in which Pasiphae and the Bull conceive the Minotaur, builds the labyrinth at Knossos, and creates the wings with which his son Icarus commits his fatal act of hubris. The parallels between life and art are intertwined: like his heroic Daedalus, Ayrton incessantly sought new ways of making and doing things.

If his erudition made him culturally eclectic, his dexterity and his acute feeling for both natural objects and effective materials gave him a magpie-like physical eclecticism. He used the skeletons of birds in paintings and collages, the skulls and bones of animals in sculpture.

All his fiction, the two novels, the prose and verse fragment The Testament of Daedalus (the precursor of The Maze Maker and, arguably, the best thing he ever wrote) and his collection of illustrated short stories, Fabrications, a kind of visual counterpart and homage to Borges’s Ficciones, dealt largely with artists and their relationship to mythology. Ultimately Ayrton was a mythopoeic figure. Once he had done the conventionally talented work on which his early reputation was built, everything that followed was deeply rooted in mythology and antiquity. A Cretan landscape would contain the shape of a female Cycladic figure; his female drawings became Oracles or the Cumaean Sybil; sculpted figures of bathers or acrobats gave way to the Minotaur or Talos. When he tired of mere figures he turned to mazes, and his most celebrated, and certainly his largest, work is a colossal maze built for an eccentric but enlightened American millionaire; and there it is, at Arkville, superbly impenetrable, and with a life-size Minotaur at its almost unattainable centre. And who’s to say who made the grander gesture, Armand Erp in paying for it or Michael Ayrton in constructing it with true Daedalian cunning? Even in his most technically complex sculptures, with their bisected heads, reflecting surfaces, Perspex dividing screens, the emotions were always as powerful as the intellect. His various versions of the Minotaur convey pity and terror and pain. How typical that he should himself describe his creation more succinctly and movingly than a critic could:

What is a man that I am not a man

Sitting cramped pupate in this chrysalis?

My tongue is gagged with cud and lolls round words

To speak impeded of my legend death.

My horns lack weapons’ purpose, cannot kill

And cannot stab the curtain of the dark.

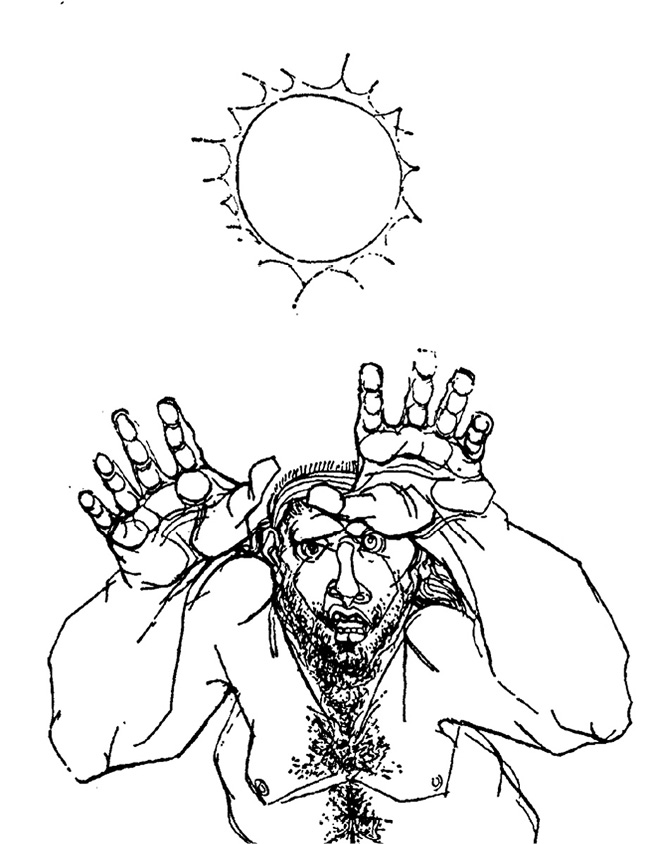

Ayrton was clearly fascinated with the nature and ambiguity of man and animal. The Minotaur was the figure that most clearly expressed his pain, while Daedalus and Icarus most deeply expressed his obsession with not merely flight but a quest for a mastery of stress, a desire to transcend disability and literally take wing. Think for a moment of what it meant from young manhood onwards to be attacked by a distressing and crippling form of arthritis that rarely left him free of pain, made it impossible for him to walk any distance, and, if he wanted to look at his interlocutor, forced him to turn his entire body to face you, since he could not turn his neck. No wonder so many of his human figures are shown in postures of stress: oracles trying to utter, or man trying to take off. Perhaps also that is why, quite often, and strangely for a man who loved women (and, particularly, well-rounded women), his female figures were sometimes oddly ungainly. Curves became angular in the way that arthritically-attacked bones metamorphose. The standing male figures in his later period did not always give the impression of being able to run, or even to walk; they seemed to be rooted in the earth, or trying to escape from it.

Like any other artist, he took himself seriously but, unlike some others, he had a capacity for laughing at himself, even for self-mockery, as in that thoroughly ingenious bespectacled, large warts-and-all self-portrait in his jacket design for Fabrications. He had the wit to attach as an epigraph to The Testament of Daedalus these lines (from Henry VI, Part III):

Why, what a peevish fool was that of Crete,

That taught his son the office of a fowl!

Michael had a habit of doing one a good turn now and again while simultaneously heaving a substantial burden, in the nicest possible way, on to one’s shoulders. Many years ago the co-editor of Encounter, in an earlier life, asked me to become art critic of The Listener. The burden for someone not yet 30, to fill the post once held by Herbert Read and Wyndham Lewis, was slight compared with Ayrton arranging with the BBC that I should fill in for him on Round Britain Quiz while he went abroad. Not only did I have to partner Denis Brogan but, said Michael, ‘by God you’d better win!’ Well, perhaps because they fed us easy questions, or because Sir Denis and I had a madly complementary knowledge of things American, we just managed it by a point or two. But it was, win or lose, quite impossible to match Ayrton’s urbanity and fearsome erudition, backed as it was by an alarming total recall. (And how odd, or perhaps how very English, that Brogan’s standing as an academic was never harmed by his quiz supremacy, but for Ayrton the artist to do the same thing represented a distinct diminution of reputation.) One last, and poignant, memory. Some time ago he suffered a painful and undiagnosed illness and very nearly died. He was so ill and drugged that even his closest friends could not see him. During that time the RAF Museum at Hendon was opened and, having two small sons, I became a regular visitor. When, at the very last moment, an intuitive neurologist finally made the right diagnosis, and a particularly vicious diabetes was controlled, I described these visits to Michael and, as the wasted flesh slowly returned and the skeletal man once again became robust, we planned a first excursion together to that splendid memorial to the brave young men and their flying machines. Michael, who despite his immobile neck was (with the aid of a few extra mirrors) an impeccable driver, drove to the great Hendon hangar which, during his recovery, had very sensibly bought one of his best Icarus statues. On the way there and back, and during our rapturous inspection of Sopwith Camels and other aeronautica (about which, inevitably, he discoursed to the Curator who had greeted us, with knowledge and authority), he expounded to me his last, tangential venture.

He had been reflecting on the nature of mirrors and the mirror image. It was his final obsession, and over the next 18 months he explored every conceivable aspect of mirror images: science, philosophy, psychology, literature, music, mathematics, physiology, architecture and art tumbled about in his brain. What first emerged was the script for a 13-part BBC TV series, and the basis of a quite revolutionary book. Michael was the onlie begetter, the scriptwriter, the producer’s right hand, and was, with that wonderful, bearded, leonine head and that seductive voice, to be the presenter and interpreter in what was clearly going to be something new in the communication of complex visual ideas to a mass audience. It was the obsessive topic of all our conversations for months as this formidably erudite man, who had not been formally educated, unfolded the ne plus ultra of enlightened, intuitive and deductive eclecticism.

On Sunday 16 November 1975, after lunch at Bradfields with Professors Moses I. Finley and G. S. Kirk, with whom he had discussed the minutiae of a translation of Archilocus which he was illustrating (a first proof of one of the etchings, his last more or less finished work, is reproduced here), he drove to his London flat. That evening he had a massive coronary and, mercifully, since he could never have put up with an inactive life, was dead within minutes.