Wyndham Lewis’s Rationbook

Reminiscences of a Lewis aficionado

This essay appeared in the Wyndham Lewis Annual, Volume IX and X of 2002-3.

Like many people of my generation, although conventionally and thoroughly taught - Perse School and Pembroke, Cambridge - most of my extra-curricular education came from the heyday of the BBC Third Programme, not to be confused with its pale successor Radio 3, now little more than an up-market Classic FM without the advertisements.

In my teens I listened to a radio drama adaptation of Wyndham Lewis’s Tarr starring one of the BBC’s finest radio actors, Stephen Murray. For me it was not just Murray’s distinctive voice that beguiled me through a long evening. Instead I was mesmerised by the authorial voice of Wyndham Lewis, which needs no gloss here. All that fuss about a frac; all that coruscating warfare between singularly unlovable characters. Nothing could have been more remote from my then literary interests, which were essentially dramatic and admirably fed by the Third Programme’s cornucopia of Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov et al. to supplement the school diet of Shakespeare and the Restoration dramatists. So Tarr was tucked away in my mind and was to remain un-read in its original form until, some time in the 1970s when, it being already clear that I suffered from advanced bibliomania, I became a serious Lewis collector and acquired a first edition.

It was not, of course, the first interesting Lewis book that I bought. That was The Apes of God in its second, 1955, edition with the wonderful jacket, of a sinister ape holding a whip, by Michael Ayrton. One of a thousand signed by Lewis it was copy number 35, had been priced at three guineas when published, and cost me thirty shillings in the tiny second-hand bookshop in Perrins Court in Hampstead, invariably visited on my way to the Everyman Cinema round the corner. Looking back, I can see clearly that, within a library that now consists of about 7,000 volumes, this simple, single purchase proved to be the most intellectually stimulating of my long bookish life. First of all it’s a preposterously engaging book. Secondly the Ayrton jacket is dazzling as an image of the book, as a piece of design and as a very typical work by Ayrton. Of course I had no knowledge at the time of the link between Lewis and Ayrton and while, alas, I never met Lewis I had not at that stage met Ayrton either. The closest I had got to Ayrton was my purchase, as an undergraduate, from the Cambridge University Contemporary Art Society, of a small oil painting called Gethsemane which Ayrton had painted in 1947 while he and Graham Sutherland were working together in Wales. (If the reader should think this an irrelevant digression by an elderly literary gent he should be assured that from this Ayrton connection flows virtually all of the Lewisiana that follows.) It cost me ten pounds. I met Ayrton a few years later when we were the judges for a painting competition in Cambridge (we were each paid five pounds in cash for our labours). It had been a dull competition and, by silent common consent, we left the gallery to find the nearest pub where we drank our fee and began a friendship that lasted until Ayrton’s untimely death in 1976. It was then that I, with much sadness because of the actual necessity, became his literary executor.

The friendship grew as I published books by Ayrton and his wife Elizabeth, and Michael and I, fuelled by the fact that our wives were both cooks of superlative quality, spent many evenings together in a relationship of much intellectual depth. It was through these discussions that I learned of Ayrton’s role as Lewis’s amanuensis in his declining years; while Lewis grew blinder and blinder, Ayrton did his book jackets and even finished off some of his half-completed drawings.

As I learned more and more about Lewis and Ayrton so, inexorably, I became a collector of both, albeit on a modest scale. The true collector will of course forgive and understand the insanity that means that my Lewis shelves contain all his first editions which are wrapped in Ayrton jackets, and my Ayrton shelves contain all the Ayrton jackets that are wrapped round Lewis books. (To me this is entirely logical. After all, one of my sons might inherit the Lewis collection, the other might get the Ayrton.)

Inevitably, since I was always an art critic as well as a publisher, I wrote frequently about Ayrton, as reviewer or as author of a catalogue introduction for one or two of his exhibitions. But I wrote only once about Lewis’s art and that was when the National Book League mounted, in 1971, a major pair of simultaneous exhibitions devoted to Lewis and Ayrton and I was invited to write the joint catalogue essay which, as examiners used to put it, compared and contrasted their visual and literary œuvres.

It would be both immodest and tedious to quote my own work of thirty-odd years ago but I shall reproduce some of the key quotations I used to illustrate the subjects of my essay. Surely there is nothing more apt or more moving about Lewis than Ayrton’s words from his essay ‘The Enemy as Friend’ reprinted in Ayrton’s collection The Rudiments of Paradise (Secker & Warburg 1971):

[I]n the Redfern Gallery, during his 1949 show ... I wandered in to find two silent figures contemplating the exhibits. One of these was Mr T. S. Eliot, dressed with quiet elegance in a blue business suit, stooped like a benevolent osprey and gazing intently at Lewis’s early self-portrait. This imposing picture shows the artist gazing stonily out from the canvas and wearing a large, fierce hat. The sole other occupant of the room was Mr Lewis himself, wearing a large, fierce hat and gazing stonily at his own portrait of Mr Eliot, a picture in which the poet is dressed with quiet elegance in a blue business suit.

I also quoted Lewis on Ayrton:

When interested by the work of one of ‘the young’, I like if possible to check up on personality and physique. For I know that this poor devil has to pass through two or more wars, a revolution, and a number of depressions. Most, I feel, will fall by the wayside - their talents will die, if they don’t. But about Michael Ayrton I entertain no anxiety; his stamina is unmistakable, since it is of a piece with the air of stability possessed by his work. At the Redfern Gallery, where he is holding an exhibition, is the classic serenity he so much prizes - even to a touch of coldness. When the women are symbolically distressed, or distracted, by the first signs of a great storm, it is but in a rhythmic trance of distraction. With Michael Ayrton, unlike the other ‘young’, we have emphasis on subject-matter. It was in Italy he found this specific material, and found himself too, I believe. He may be the bridge by means of which the British ‘young’ move over into a more literary world again. Michael Ayrton is one of the two or three young artists destined to shape the future of British art.

The resonance of that quotation both then and now was enormous. In part it was because one of my idols was praising one of my friends. In part it was its source, one of Lewis’s reviews of 1949 as art critic of The Listener.

In part also it was because in the 1960s I had accepted an invitation to become art critic of The Listener myself. At the time it seemed an awesome responsibility to sit in the chair once occupied by Herbert Read and Wyndham Lewis. I had only minor qualms about Read since he was an author whom I published and was also a friend and we often discussed contemporary exhibitions. But Lewis was, for me, a long-dead God-like and fiercely irascible figure and I did not want to be haunted by him and subjected by his ghost to the sort of indignities he had visited upon Bloomsbury.

The other quotation in my essay to be re-quoted here reinforced that last point. I had by that time acquired the first edition of The Apes of God, the one done in 750 signed copies, with the jacket by Lewis himself, and I had dipped into it again to savour his mordant attacks on the Sitwells.

How then could I not quote Auden’s lines:

The Sitwells were giving a private dance

But Wyndham Lewis disguised as the maid

Was putting cascara in the still lemonade.

*

To me there are few nicer serendipities than that one of the powerhouses of posthumous Lewis activity should be a rambling, medieval house, partly built in the eleventh century, and once owned by that hyper-elegant and fastidious man of letters Sir Francis Meynell, creator of the Nonesuch Press, that great monument to scrupulous editing of definitve texts and flawless design and book production standards. His house, Bradfields, on the Essex-Suffolk border, was, until Michael died, the ever-hospitable home of Michael and Elizabeth Ayrton.

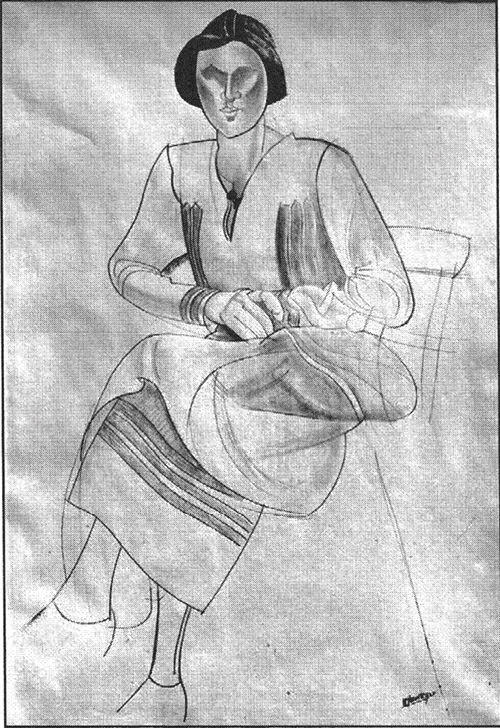

It was at one of the many weekends my wife and I spent there that I met the American scientist and Lewis expert Walter Michel and learned that his life work was the catalogue raisonné of Lewis’s art. Apart from the fact that Michel was a thoroughly delightful man, it was also a personal pleasure to be able to tell him that I was the new owner of Woman Seated on a Chair, the portrait sketch of Iris Barry (who had borne Lewis a son), which I had just bought for £200 from the Piccadilly Gallery and whose new provenance Michel duly noted. (Barry’s son Peter was, until his death, a member of the Wyndham Lewis Society.) The rest was boring, technical publishing talk which resulted in the eventual successful publication of Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings by Michel under the Thames & Hudson imprint in 1971. Apart from providing the picture known as Michel number 498, I had made my first significant contribution to Lewis publishing.

Woman Seated on a Chair (M498) – Photograph by Raphael Munton

At about the same period my wife and I were just packing our bags one Saturday morning to drive to Bradfields for the weekend when Michael Ayrton phoned to ask whether we could give a lift to Hugh Kenner who was to be a fellow guest. To which I responded rather ungraciously that that depended on how big Kenner was. ‘Same height as me but thinner’, said Michael. ‘Why does it matter?’ ‘Because’, I said, ‘he has to fit into the back of our Mini.’ So we crammed this great academic figure into our Mini and another Lewis link was forged, and I persuaded him to write the luminous introductory essay that prefaced Michel’s study and gave it the academic clout that I needed to sell a substantial American co-production to the University of California Press. (Incidentally Michel is, of course, long out of print and the most recent copy I have seen in a specialist second-hand art bookshop was priced at £400.)

My other contribution to Lewis studies in that same year was the invaluable collection Wyndham Lewis on Art, edited by Michel and the indefatigable C. J. Fox, one of the few Canadians to have rated his fellow citizen as he deserved.

Hugh Kenner was also responsible for another, to me even more interesting, piece of Lewis publishing. To my shame, lessened to some extent by the fact that Ayrton had not heard of it either, I knew nothing of The Roaring Queen, largely on the grounds that it had never been published. Hugh maintained that the only extant copy was a proof of the Jonathan Cape edition in the University Library at Cornell. So I phoned my friend Roger Howley, the director of the Cornell University Press, and persuaded him to have a photocopy made and sent to me at my office in Secker & Warburg to which publishing house I had by then moved. I read it with immense joy and saw at once why, no matter how outraged Lewis had been at the time, Cape could not have published it in the 1930s. All my publishing life I had been plagued, as were my colleagues and competitors, by libel writs, and as The Roaring Queen had virtually undisguised scabrous portraits of, among others, Arnold Bennett (Samuel Shodbutt), Walter Sickert (Richard Dritter), Virginia Woolf (Rhoda Hyman) and Brian Howard (Donald Butterboy), I could entirely sympathise with Cape’s inability to go ahead. The only character who would not have sued was Nancy Cunard (turned by Lewis into Baby Bucktrout) since she had originally wanted to publish the book herself, but felt unable to pay the needy Lewis an advance.

Interestingly, although Jonathan Cape, Secker & Warburg and virtually every other London literary publisher had been put on notice that they would have been sued for libel if they were to publish Heritage, the autobiographical novel by Anthony West containing a fairly cruel attack on his mother Rebecca West and a portrait of his father H. G. Wells, thus effectively suppressing the book in England until after West’s death, she was not thought to be a threat to The Roaring Queen in the thirties. Victoria Glendinning has however stated in her biography, Rebecca West: A Life, that Rebecca believed herself at the time to have been the origin of Stella Salton.[1]

Ironically, there is one other significant character in The Roaring Queen, a thoroughly venal book reviewer (other than Arnold Bennett), called Geoffrey Bell. He was none other than Gerald Gould, father of Michael Ayrton. Michael only discovered this, at the same time as me, when he read the photocopy I made for him.

I was myself ready to publish, with an introduction by Walter Allen to set the book against its 1930s literary and political background and a jacket design of course by Michael Ayrton - it was a fine caricature of Arnold Bennett in his prime - when I experienced that moment of dread which so many publishers occasionally feel, when they know something might go wrong.

Publishing in my time had become increasingly bureaucratic but in the twenties and thirties it was much simpler. I suddenly thought - the Secker edition was by that time in page proof form and had been announced in our catalogue - that it was more than likely that in those carefree, unbureaucratic days no one would have bothered to cancel the contract for a book withdrawn for fear of a libel action, and that there was a strong probability that the house of Cape still held a valid contract, with an exclusive licence to publish, for The Roaring Queen. Happily Graham C. Greene, nephew of the novelist and managing director of Cape, was a good, if competitive, friend and I went to see him in his Bedford Square office and explained the circumstances. Good fellow that he was, and is, he checked the Cape contract files, confirmed that my suspicion was correct, but stated that he would not interfere with our arrangements with the Lewis estate.

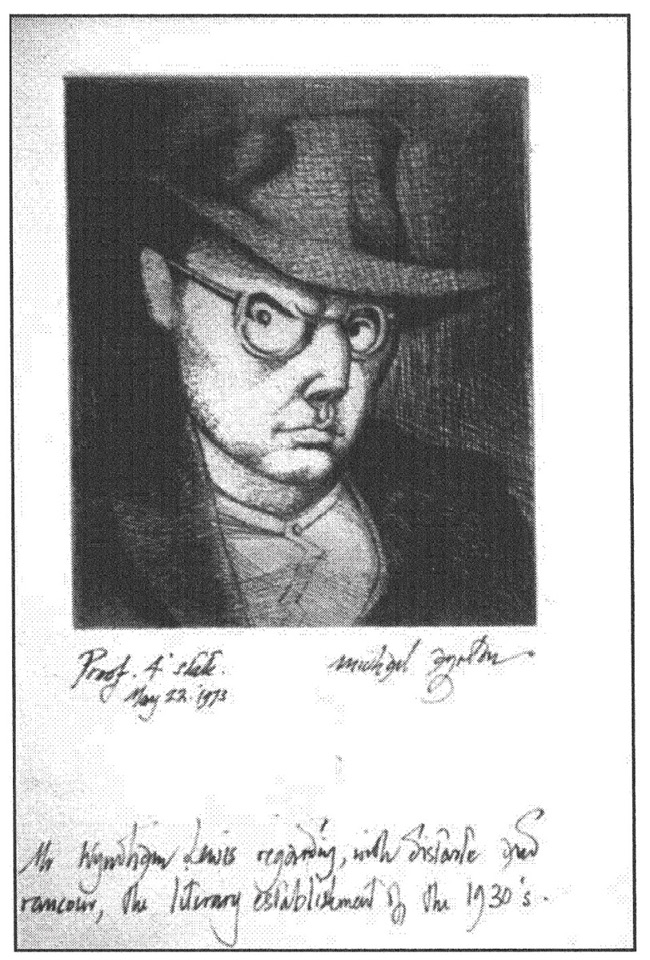

I celebrated this happy escape by publishing a special deluxe limited edition of the book, of which only 100 copies were for sale, signed by Mrs Wyndham Lewis, Walter Allen and Michael Ayrton, whom I had commissioned to do an etching for the edition. Michael produced a marvellous portrait of Lewis in hatted, Tyro mode, with the title ‘Mr Wyndham Lewis regarding, with distaste and rancour, the literary establishment of the 1930s’. When the limited edition had been properly bound and boxed, I asked Graham Greene to come to my office for a drink and presented him with one of the out-of-series copies to demonstrate that it isn’t always true that no good deed ever goes unpunished.

The relative success, no matter how belated, of the first publication of The Roaring Queen prompted me to do a new edition of The Revenge for Love which I felt had been out of print for far too long. I had become friendly with Julian Symons and I persuaded him to adopt the Walter Allen role and write the long background literary essay to set the book in its context for 1982. So it was only natural that, in our discussions over lunch one day, after I moved on to run André Deutsch, our shared enthusiasm for Lewis should lead to Julian’s admirable anthology The Essential Wyndham Lewis, edited and introduced by him with his habitual incisive authority, and published in 1989.

Among my more treasured volumes is Julian’s first book, the collection of poems entitled Confusions About X, undated but published by the Fortune Press in the late thirties. As Lewisites will know it contains as a frontispiece Lewis’s superb ink-drawing portrait of Symons. Having discovered the book for a modest sum in the Charing Cross Road I got Julian to inscribe it to me, and he wrote me a note in December 1990 which, to me at least, sums up the essential integrity and humanity of one of Lewis’s staunchest supporters:

A note for Tom Rosenthal, December 1990: ‘X is the kiss of the unknown’ - I am not sure whether I derived a title from that line of Roy Fuller’s or whether Roy took his line from my title. Anyway, that was the idea - to express confusion about the unknown, about what was going to happen. I only wish the poems, some jejune, others barely comprehensible, lived up to the title. Are just two or three less than shameful? I hope so. What’s certain is that none of them are deserving of the splendid Lewis drawing, done in less than half an hour, which seems to me one of his finest pieces of the late thirties.

Inevitably, in a lifetime of compulsive collecting, one is going to pick up quite a few oddities, ranging from the Chatto & Windus 1919 illustrated monograph on Harold Gilman by Louis F. Fergusson with an introduction by Lewis, to a copy of the not very interesting Madness in Shakespearian Tragedy by H. Somerville, which also carries an introduction by Lewis.

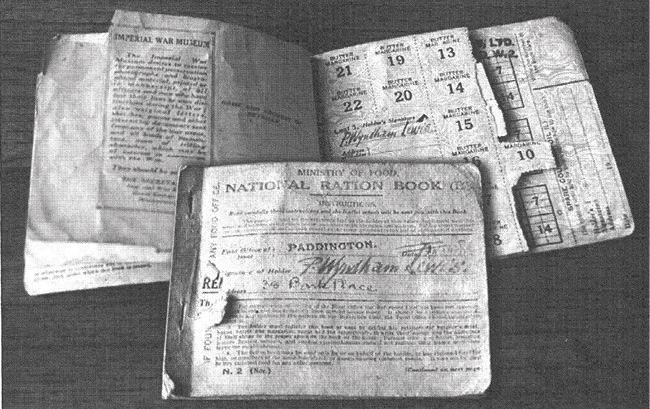

I also own copy number one of the 79-copy signed limited edition of The Wild Body. Among other treasures is The Ideal Giant, signed in 1917 by Lewis ‘With the author’s kind regards’, but there is alas no evidence of who was the recipient of those regards. I had spotted it, at an exorbitant price, in a Modern Firsts catalogue issued by an academic and then provincial bookseller in Leamington Spa called R. A. Gekoski. I phoned him to say that the price was ludicrous and was there anything to be done about it. Rick was, and is, a very shrewd dealer and refused to discuss the price but said that when he was next in London he would visit me and show it to me. So he brought it to my office and, of course, once I’d seen this bizarre artefact, one of a printing of 200, and that heavy, spiky black ink inscription I was done for, but at least I was able to bargain the price down from ludicrous to merely outrageous and Rick has become a friend for life to me (if not to my bank manager), as well as the leading London dealer in Modern Firsts. He has been designated in my will to be the man to sell my library (including all my Lewis books) if my family don’t want to keep it when I pop my clogs. But nothing is quite so odd as a find in New York, namely Lewis’s ration book. To someone with an impoverished wartime childhood in Manchester who remembers rationing all too clearly, this was an irresistible purchase which has given me particular pleasure. But it was only as I was looking more closely at my Lewisiana to prepare for the accuracy required of this article that I examined this fragile document with a magnifying glass and discovered that it is not a cousin of the ration books my mother struggled with at home while my father was doing his bit in Egypt. Nor is it, as I had carelessly assumed, from World War II when, as I knew via Ayrton, T. S. Eliot used to help out the Lewis household with the odd care package from Fortnum’s and occasional bottles of champagne. The ration book in my possession is from World War I. It was issued at Paddington, has the serial number N27 NO.898373 and bears the rubber stamp of Whiteley’s of Queen’s Road W2, a ‘Butter & Margarine retailer’. The ‘signature of holder’, repeated several times, reads P. Wyndham Lewis and the date is indubitably ‘29.11.1918’. The address is given as 38 Bark Place. Interestingly enough the bulk of the meat coupons are unused. Will this spawn a thesis that Lewis was a vegetarian, or does it mean merely that he was too broke to afford meat?

My relationship to Lewis is not a simple one. As the London-born child of German Jewish refugees who fled to England as early as 1933, and as one who was brought up as an orthodox Jew, Lewis’s political attitudes as expressed in the early thirties, notably in his book Hitler of 1931, were not so much problematic as repugnant. When one is young, tolerance and maturity are not one’s strongest suits. It was this attitude that made me refuse to speak German after September 3 1939 - I had been until then bilingual - and to refuse to learn the language at school until it was too late and I realised only in my twenties how foolish I had been.

Two views of Lewis’s 1918 ration book – Photographs by Raphael Munton

But gradually I learned a little wisdom and began to understand that Lewis’s anti-Semitism and espousal of Fascism was simply endemic among vast tracts of the intellectual classes in England and Europe, and he was just a part of a movement that included T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and others whose dislike of Jews was an unthinking knee-jerk tic based on prejudice and lack of knowledge. After all, Michael Ayrton, himself a Jew (a member of the Zangwill family), and someone who could spot an anti-Semite at a hundred paces, worshipped him. And, most importantly for me, Lewis, unlike Eliot and Pound, changed his ways and even recanted. To the best of my knowledge Eliot never acknowledged error in that department. And Pound of course we all know about. Lewis published two entire books which, while hardly an apologia for Judaism, were at least a powerful setting-straight of the intellectual record of anti-Jewish race hatred.

His The Hitler Cult of 1939 was a powerful anti-Nazi polemic. ‘A Sunday School of Sunburnt State paupers armed to the teeth’ is a vintage Lewis condemnation. There is something very prescient in the J. M. Dent blurb - remember that this was written in 1939, before the war had begun:

And finally it is predicted that this ‘Marxist Cecil Rhodes’ will be less lucky than was the famous Englishman, not having Mashonas and Matabeles to deal with; that this latter-day Rotarian Caesar will lose the Empire he has, rather than acquire a new one.

The comparison with Rhodes is absurd and the remarks about the Mashonas and Matabeles are offensive to modern ears, but he stated clearly the unfashionable view - assuming that, like most polemicists, Lewis wrote his own blurb - that Hitler was loser rather than saviour.

In the same year Lewis published The Jews: Are They Human? In his Foreword he wrote:

‘Jews are news.’ It is not an enviable light that beats upon the Chosen People ... Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Czechoslovakia and other countries, are freezing out their Jewish minorities by means of what has been described as ‘cold pogroms’ ... The governments of those foreign counties regard their Jewish citizens as ‘undesirables’’. It is the intention of the Hitler government, for instance, to have made Germany Judenrein [Jew-free] in two years’ time. This would entail the migration of 600,000 Jews.

There is dreadful irony in any contemporary contemplation of Lewis’s statistics but, I stress, he was writing in 1939 and this book is, as a whole, a thoughtful, thoroughly humane and decent work for its time, even if to our ears today it sometimes reads patronisingly.

I therefore had little difficulty in coping with Lewis as a whole. The early blind spot about the Jews faded against the powerful searchlight of Lewis’s remorseless pursuit of the Enemy, of the scourge of Bloomsbury and the Sitwells, of the probing intelligence of this great iconoclast.

Looking again at my shelves and walls, I see other mementos of his genius. One of them gave me the only bad moment in over forty years of collecting. An antiquarian bookseller’s elaborate catalogue reached me at home one morning and, spread over two pages, there was a fine set of the Ayrton-jacketed Methuen editions of The Human Age, plus some of Ayrton’s sketches for the illustrations and the framed dust-jacket artwork for Volume One. Now it so happens that there hangs in my office the original jacket artwork for both volumes which I bought from an Ayrton dealer several years earlier. Within seconds all sorts of explanations and permutations passed through my mind. One, that the antiquarian was bent and was selling a forgery. Two, that the art dealer I bought from was likewise bent and a purveyor of fakes. Three, both merchants were honest and had been duped by a forger, and so on. None of these explanations was probable and none made sense, not least because the price quoted was not that high, Ayrton was not in the league of artists who attracted forgeries and, on the principle that in the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king, I knew Ayrton’s Lewis-orientated work better than anyone else in England and was not likely to be taken in by such a fake.

Michael Ayrton, Mr Wyndham Lewis regarding, with distaste and rancour, the literary establishment of the 1930’s, 1973 - Photograph by Raphael Munton

So I counted to ten, drank a cup of strong coffee, put the catalogue into my briefcase and travelled to my office. There I made as careful a comparison as is possible between an actual painting and a photograph of another one, and was able to dispel all my brief, paranoid fantasies. Mine’s OK and so was the one in the bookseller’s catalogue. The two were very similar but looking at them and recalling four decades as a book publisher who used to drive most of his jacket artists crazy, I realised that Ayrton had in fact made two different versions of the same subject, either to satisfy himself, or the near-sightless Lewis, or at the whim of the publisher who wanted some changes to accommodate the lettering. Peace broke out again in my household.

On the same little Wyndham Lewis wall I also have one of Ayrton’s pencil sketches of the great man, complete with eye-shade/visor, and the artwork for Ayrton’s jacket of the Methuen edition of Self-Condemned. At home I have the only monotype I’ve ever seen by Ayrton. It depicts in stark black and grey the sinister figure with the Mr Punch-style stocking hat that appears on the spine of the jacket of the second volume of The Human Age containing Monstre Gai and Malign Fiesta. Collectors of Lewis arcana might care to know that this edition is dated 1955, whereas its companion, the first volume of The Human Age containing Childermass, is dated 1956. The last section of these reminiscences concerns Lewis’s masterpiece the Red Portrait, which is reproduced on the front of the jacket of Michel’s catalogue raisonné. I only saw the original once, about twenty years ago in the Crane Kalman Gallery in Knightsbridge. I was an unsuspecting lunchtime stroller, attracted to the gallery by a fine L. S. Lowry in the window. Suddenly I was face to face with that wondrous evocation of Froanna and I stood and stared at it for a least a quarter of an hour. Andras Kalman asked me why I was so interested and I explained my reasons. ‘So why don’t you buy it?’ I asked the price and he replied ‘£125,000’. I said that I thought it a perfectly fair price but that, with a mortgage and two young children, I didn’t even have 125,000 shillings, and left; although I would check up on it occasionally until one day it was gone. Kalman perfectly properly refused to tell me who had bought it.

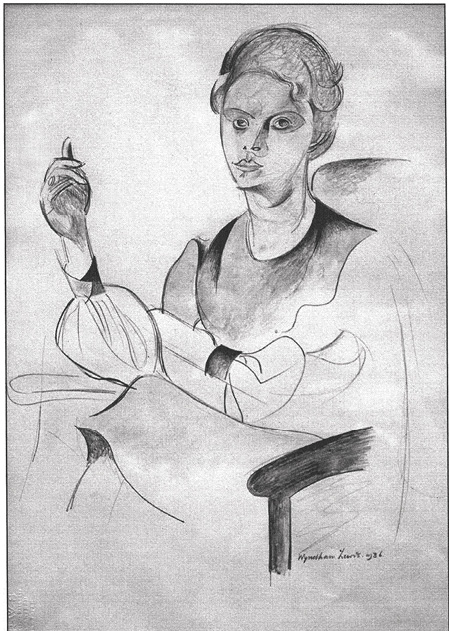

In the meantime Elizabeth Ayrton, no longer happy to live at Bradfields after Michael had died, decided to move to the West Country and to dispose of some pictures. She knew how much I admired a wash and pen drawing, catalogued in Michel as number 883, ‘Young Woman Seated 1936’. Michael had been particularly fond of it, not least because Lewis had given it to him, and it was the sketch for the Red Portrait. Elizabeth asked me if I wanted to buy it and I said yes at once, but because so many years of friendship were involved, I also said that she and I could not possibly talk about the price. I suggested that Michael’s dealer be asked to put a fair market value on it and if I could afford that sum I would buy it. If not, she should sell it through the usual channels. Happily the price set by the dealer was affordable by me and Young Woman Seated has been on the wall of my study ever since.

Then, last year, I read in the Lewisletter of the Wyndham Lewis Society that the original of the Red Portrait was now the property of the Wyndham Lewis Trust and could be seen, by appointment, at the Courtauld Gallery. Apart from being able to see it again, of course I wanted to know how and why this had happened. I phoned the editor of the Lewisletter and explained why I wanted to know and could he please inform the donor of my interest and ask the donor whether he or she would be prepared to speak to me.

That same day I had a phone call from Graham Lane, a distinguished retired architect (a former partner in Sir Denys Lasdun’s practice and a dyed-in-the-wool Lewisite). He told me that the buyer from Crane Kalman was a Swedish industrialist who had fallen on hard times and been forced to sell at least half of his collection at Christie’s. Lane had noticed it in the sale catalogue, had hoped for a quiet day in the saleroom, been lucky, and had bought it for about a third of the Crane Kalman price. Lane then, in a remarkable act of generosity, had given it to the Wyndham Lewis Trust to be housed at the Courtauld.

Although infinitely less generous than Lane, I did feel passionately that, at least after my death, oil painting and sketch should be united and available for joint study. So, using the excuse of having to re-draft my will anyway because of the arrival of my first grandchild, I have bequeathed that beautiful sketch to the Trust, together with the Ayrton sketch of Lewis, and the original Ayrton artwork for the various Lewis jackets which I own. It seems a very reasonable recompense for the endless pleasure and fascination Lewis as writer and artist has given me over a lifetime.

Young Woman Seated, 1936 (M883) - Photograph by Raphael Munton

1 Heritage was in fact then published by me at Secker & Warburg. The book had been published without difficulty in the United States, where the libel laws are much more relaxed.