Lowry in Person

‘Solitude is the school of genius.’ - Edward Gibbon

Just as those ignorant concerning Lowry’s art use the phrase ‘matchstick men’ so those who know little of his life refer to him as a recluse on the grounds that he lived alone in a small house in a remote village. The recluse cliché is just as absurdly wide of the mark as the matchstick men label. Recluses don’t on the whole travel all over Britain, take holidays by the seaside, carry on correspondences with punctilious correctness nor, above all, do several broadcasts and countless interviews. The several editions of Shelley Rohde’s biography of Lowry and various reminiscences of him by people like his sometime dealers, Tilly Marshall or Andras Kalman, are full of non-reclusive information about him, some of it interesting, some of it, as in the case of Tilly Marshall’s book, unpleasantly revealing about Lowry’s personal habits as if the author were revenging herself on his frequent sponging off her and her husband’s art gallery which had, admittedly, done so much for the artist in the North- East. In fact her husband, the guiding spirit of the Stone Gallery in Newcastle, Ronald Marshall, showed and promoted Lowry’s work with great skill and enthusiasm. He managed, without denting the success of Lowry’s London dealers, to enhance Lowry’s country-wide reputation and acceptance.

Shelley Rohde was not really a biographer, although, as a working journalist, she was a dedicated truffle-hound, and her definitive identification of Lowry’s mythical female bel idéal is quite compelling. Because the books are, ultimately, fascinating collections of anecdotes and the reminiscences and correspondence of Lowry’s carefully maintained, but always separated, friends, they are, even if somewhat artlessly written, full of vital information; but Lowry still awaits a biographer who fully understands the nature of the subject’s art and, the narrative skill to interweave the art with the life and thus makes, sense of it as Hilary Spurling has done with Matisse, David Cairns did with Berlioz, and as John Richardson (at time of writing at least) is so heroically doing with Picasso.

Nonetheless the most casual reading of Rohde makes it clear that Lowry was, although a lifelong bachelor, the least reclusive of men, who had long friendships with fellow artists, distinguished academics, a handful of key patrons and a succession of young women.

Lowry was not a recluse but a solitary and, in Gibbon’s lapidary phrase, solitude is the school of genius. After a lifetime of work and friendship with living artists I have not known a single great painter or sculptor who was not totally ruthless about his work, which always came before everything else. The principal advantage of being a bachelor and celibate artist is the obvious one of the lack of family ties and therefore a responsibility to no one except oneself in organising one’s hours. Thus his single-mindedness about his art - which in other circumstances one could term artistic ruthlessness - was easy to satisfy while not being too obvious to alienate friends. Once his control-freak, bedfast mother died he was a free man at last; free to paint all night if he chose to; free to live where and how he liked; free to be, albeit gregarious, a solitary.

My first encounter with Lowry was in 1960 when I visited Manchester on business. I was the assistant sales manager of an art-book publisher and I was calling on the local booksellers to try to boost trade. Having spent my childhood in the city, it was a welcome return to old haunts, so I stayed over for the weekend and arranged to lunch with an old Cambridge friend. Lunch was at his parents’ house in Mottram-in-Longdendale just over the Cheshire border. My friend’s father was, among other things, the Treasurer for the annual Mottram Show and, as such, was a friend of the village’s most celebrated citizen, L. S. Lowry. I persuaded my friend to take me round for a visit.

The door was opened slowly and reluctantly by the artist. He greeted David with just enough friendliness not to offend and regarded me with considerable and doubtless justified suspicion - a stranger arriving unannounced on a Sunday afternoon. At that time Lowry was 73, about six feet tall, heavily, solidly built but not overweight, with a lot of short grey hair, heavy spectacles, and oddly imposing in a paint-spattered, dark three-piece suit and one of those thickly textured striped shirts with neither collar nor tie.

Far from looking like an artist, he was every inch the retired rent collector that he was, the kind of man you’d see nursing a pint of mild, sitting by himself in the snug of a thousand pubs in the North West.

Lowry grumbled at us for not having warned him of our arrival, complained that we had caught him unawares in his painting clothes, and generally made us, me in particular, feel like unwelcome intruders. While Lowry made us some tea, I prowled around the front room of the modest two-up two-down stone house. It was a chilly day and the room, despite a small, two-bar electric fire, was cold and David and I kept our coats on while I scanned the walls for examples of the artist’s work.

There were none; just some nondescript pieces of Victoriana: but there was one quite staggeringly beautiful drawing of a woman’s head. I don’t know where it is now, but I have still got a clear impression, after over fifty years, of a luminous, clear-eyed face, a mass of hair and the powerful blackness of the line. It was large, probably about 20 inches high by 16 inches wide, and dominated the wall by the sheer force of a significant work of art surrounded by dross. When Lowry brought in the tea I ventured to say that I admired the drawing.

‘Oh, do you like it?’

‘Yes’, I lamely replied.

‘Do you really like it?’ he persisted.

‘Yes, really, it’s magnificent.’

His somewhat closed and wary face relaxed a little and he offered the smallest hint of a smile.

‘Do you know who did it?’ he asked in the tones of a pedagogue who knew that his floundering pupil would not know the answer.

‘Well, Mr Lowry, I can’t be sure’ - the drawing was unsigned - ‘but it could be a Rossetti.’

‘A Rossetti, eh?’ and he looked wickedly in my friend’s direction with the unspoken subject of ‘how could you bring this idiot to spoil my Sunday afternoon when I’m busy painting?’

He then looked at me and said, ‘Well, you’re quite right. It is a Rossetti and I love it more than any other drawing I’ve ever seen,’ and what the Sovietologists used to call a thaw began to set in.

After some desultory chat, about not very much, I dared to compliment him on a magnificent long-case clock in the corner, the only piece of furniture in the room that you wouldn’t have to pay someone else to cart away. The inquisition proceeded on similar lines to the earlier one.

I swore that I really admired it, so Lowry, of course, asked me to identify its maker. Now, while I do know a little about art, antiques are, for me, mostly terra incognita. But I was extraordinarily lucky. The only great English clockmaker whose name had impinged on my brain was that of Tompion. So it was double or quits time and I named him as tentatively as I could.

‘Right. Yes. It is. A Tompion, yes.’ He looked wonderfully gleeful, which seemed a little excessive as a reaction to my mini-quiz. But the glee was not for me. It was for himself. ‘Do you know where I got it? A Tompion. Yes?’

He paused to let me give the obvious negative response and then, marvellously animated and sounding like that old North-country radio comic, Al Read, he told us that he’d found it “in a junk shop in Rochdale. The owner didn’t know what it was. It didn’t work and it was all covered in dust and muck and he wanted ten bob for it. Ten shillings for a Tompion. He were blind. Blind and daft with it. So I offered seven and six and he took it. Of course it cost me a few bob to have it restored, but just you listen to it when it strikes.’ Which, ten minutes later, it did, and when the sound had faded away he chuckled again. ‘A Tompion, oh yes. He didn’t know, that fella in Rochdale. A Tompion.’

Al Read was born in Salford on 3 March, 1909. He began his career as a comedian only in his 40s, having been appointed at 23 as a director of the family meat packing business. This had been founded by his grandfather, the first man to produce tinned meat. He did his first broadcast on 10 March, 1950 and was given his first ‘Al Read Show’ in September 1951, but no matter how successful would not do more than one show a month. Like Kenneth Horne of ‘Much Binding in the Marsh’ fame, who was chairman of a paper manufacturing business, he would not give up the day job. But, following a Christmas performance for the Royal Family at Windsor, he recognised his talent and his ensuing celebrity and, in 1956, sold his business and became a full-time performer with his perennial catchphrases ‘Right monkey’ and ‘You’ll be lucky’. Physically he was the antithesis of Lowry, conventionally good-looking, immaculately groomed and smartly dressed, with a light, attractive voice, whereas Lowry was, doubtless deliberately, scruffy, indeed shambolically turned out, with a much deeper voice. But their accents were identical and they shared a genuinely sardonic sense of humour, at once sly and dry, and, while Lowry would have died rather than perform on a public stage, whenever I was in his company and listening to him talk, complain or mock some pretentious critic or would-be patron, I always heard the vocal tones and spirit of Read. Read died, aged 78, in 1987 but some of his radio programmes were still being repeated at the beginning of this century and are still available on recordings.

By this time Lowry was beaming and his somewhat mournful countenance was transformed so that I at last felt able to ask whether it would be possible to see some of his work.

‘Well you’d better come into the back room, then. It’s very dirty, mind. You’d better watch that fancy coat of yours. Don’t want to get paint on it.’

It was the invitation I had not dared to hope for - and yet finally I was entering the studio of L. S. Lowry. It was indeed dirty, chaotic, apparently disorganised. Paintings, both finished and unfinished, leaning against the walls, facing outwards or with the backs of the canvases and boards turned towards us. On the easel was a barely begun townscape. I was, after years of schoolboy and undergraduate enthusiasm, in my own private heaven. After another lengthy catechism, I was led in. It was, particularly to someone who had played in the streets that he depicted so vividly, had attended a primary school of the kind he painted, had seen the factory gates and the football crowds that so fascinated him - an overwhelming experience that many visits over the years to the old Salford City Art Gallery, with its great Lowry collection - since transferred to the Lowry arts centre, which opened in April 2000 - have never eradicated.

Against the serried and carefully curated ranks of a formal gallery, the higgledy-piggledy randomness of a messy artist’s studio will always win in terms of both physical experience and aesthetic appreciation. Without glamorous framing and ultra-sophisticated spotlighting, and with only a couple of unshaded 100-watt bulbs for illumination, one’s perceptions become both immediate and stark, with little opportunity for careful reflection, so that the magic of that exposure to his art was as deep as it was unforgettable.

At 24, and without the benefit of Shelley Rohde’s 1979 biography, or the relentless cascade of confessional and gossip-ridden journalism since 1979, I did not dare ask him about the identity of the girl with huge eyes and centre-parted glossy black hair who stared at us from a particularly powerful canvas. Which is just as well, since she never existed, being an amalgam of several young women of a certain physical type whom he befriended but never touched.

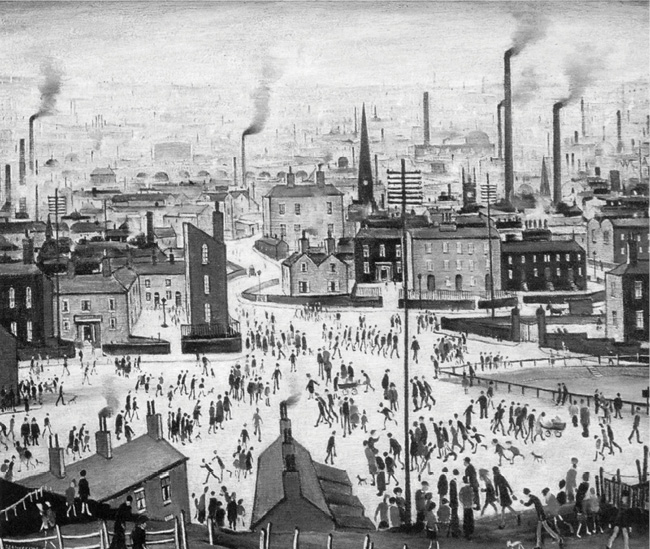

What was so striking, apart from the obvious impact of the townscapes, teeming with what the ignorant call his ‘matchstick men’, was the extraordinary individuality and scrupulous differentiation of the hundreds of human beings then all within a few feet of my gaze.

I made what stumbling conversation I could, offering my jejune opinions on art in general and of his own work in particular and, by sheer luck, managed not to dispel his cheerful mood. Lowry, often wrongly described as a recluse and a loner, was in fact not only gregarious but an acute, drily witty talker. Just as his paintings, far from being naïve, are immensely sophisticated in both their composition and their humour, in private speech he himself was simple, direct, yet perceptive about his art - as I was to discover not only on that bleak winter afternoon but in later, more formal encounters when I was armed with a tape recorder.

As it got dark outside I felt that we should not outstay what had turned into a genuinely warm welcome, but the incipient collector in me would not be still, so I asked if it would be possible at least to consider acquiring one of his pictures. Another catechism about liking his work came and went and he then asked me which picture I fancied. Unerringly, having no idea as to his prices, apart from knowing that they would be far beyond my means, I pointed at the smallest one. Done in oil on board, it measured only 6 ⅝ inches high by 5 ⅝ inches and contained a group of three people, a girl with her back to us, another, older, girl facing us, a small boy in a red sweater, and half a dog. In the classic Lowry white background there were some barely visible, vertical black streaks, indicating the possibility of some factory chimneys in the distance; at the bottom, a black strip that simultaneously represented the kerb and unified the structure of the picture.

‘Oh, do you really like that one?’

‘Very much, but of course I don’t know if I can afford it.’

‘Well, what do you want to pay for it?’

As a tyro publishing executive who had not yet paid off all his student debts and whose take-home pay was £11 and fifteen shillings a week, this seemed an insoluble problem. I knew nothing of prices and values.

So I told Lowry that I would happily give him all the money I had on me. This was in the days when ‘unless prior arrangements have been made with the management’ - hotels did not take cheques and there were, of course, no credit cards. I had therefore drawn from my employers a cash advance of £15 to cover the expenses of my trip.

I reckoned that I could borrow some cash from my friend who would take my cheque, so that I need not spend the next week washing dishes at the Midland Hotel, and extracted the three five-pound notes and nervously proferred them to the great man. Being an exceptionally kind man, he took them and said that that price was fine by him if it was fine by me, and how would I get home? I assured him of my return ticket and decided not to mention the hotel.

‘But do you really like it?’

I again swore my undying love for the picture, whereupon the old devil, which, to some extent he really was, said: ‘But it’s not finished. I tell you what, I’ll finish it and send it on to you. David will have your address.’

I offered some mild platitudes about being unable to bear being parted from this great treasure.

‘All right then. I’ll finish it for you now.’

I muttered my gratitude and wondered how so small a panel could perch on his easel. It didn’t. He had vast hands and he held it comfortably in his left while spending the next thirty minutes with a series of small brushes in his right.

It was only many years later that I discovered that there were senior Royal Academicians who considered him an amateur, a ‘Sunday painter’. They’d clearly never seen him at work. He was right. It wasn’t finished but at the end of that half hour it certainly was. A highlight here, a black line there, a deepening of the red, a thickening of his heavy, greyish white and it was an unmistakable finished Lowry work of art. I examined it more closely and saw that it had in fact already been signed: this picture, ‘finished’ in 1960, was actually dated 1957.

Then the old tease put it on the easel and proclaimed that while it was indeed now finished it was still wet and would have to remain with him for a few more days to dry and then he would dispatch it to me.

Somehow I managed not to gibber but persuaded him to let me pack it up in some silver foil he had in his kitchen and gave him an assurance that I would keep it upright and free of all harmful contact until I got it back to London.

After that there was occasional correspondence but I wasn’t to meet Lowry again until the autumn of the following year, 1961. Again it was at his little stone house; now I was accompanied by the poet and, at that time, senior BBC Third Programme talks producer Anthony Thwaite. I interviewed Lowry for a radio arts programme called New Comment. It was not my skills as broadcaster but Lowry’s spellbinding talk that made the transmission get the highest ‘Appreciation Index’ of any item broadcast on New Comment that year. We spent hours with the tape running because neither Anthony nor I could bear the thought of cutting off his flow of reminiscences, his views on art and on his own work.

Unfortunately no copy still exists of the sound tape but what follows is an edited transcript of the actual broadcast transmitted on the BBC Third Programme (now known as Radio 3) on Wednesday 8 November, 1961:

Rosenthal: I think one thing which most people would agree about, - Mr Lowry, is that your work is the most natural and, in a better sense of that word, uninhibited. Have you had a great deal of formal training in your painting?

Lowry: I went to the Manchester School of Art but did nothing but the antique, preparatory antique, and laughed for a long time but did no painting at all at the School of Art. I went to a private portrait painter - William Fitz, for painting lessons. He guided you also: you used your own colour: you did what you liked but he simply guided you.

Rosenthal: There is in fact absolutely nothing academic in your work. This is because presumably you picked up what you wanted to pick up and that was all. Is that a fair thing to say?

Lowry: Well, I did things in my own way, as I see them, without regard to anybody or anything else all my life really. I’ve seen these industrial scenes for a long time. Since 1919 to be quite exact. And I’ve just done them as I saw them without regard to anything else.

Rosenthal: Talking of those industrial scenes, an awful lot of people first of all, they don’t understand your work. I think because they immediately say that your work is depressing. But those I think are the kind of people who would say that the scenery is depressing simply because they can’t see it. I was brought up as a child in Manchester, I’ve seen the things you’ve painted, for many, many, years. I can see their beauty - I love them. A few others do too but not very many. Can you explain why it is that the beauty of those things is not immediately apparent, yet you yourself have managed to put over the beauty of this landscape with, I think, outstanding success?

Lowry: Well, I suppose it’s the way I looked at it. We went to live in Pendlebury in 1909 on the other side of Manchester... At first I disliked the scenery very much indeed, and then I got used to it, and then I got interested in it, and then I got to like it somewhat, and then after quite a while I got obsessed by it.

Rosenthal: I’m glad you used the word ‘obsessed’ yourself because I wanted to use it, and often I think it is an impertinence to suggest the word. But I couldn’t help feeling that, for example, in your last show, there were two paintings there which are not from this area as it were; there is a large painting of London’s Piccadilly Circus and a very large one of Ebbw Vale. And yet it seems to me that the obsession which you mentioned with the landscape had carried you along, to Piccadilly and to Ebbw Vale.

Lowry: Yes.

Rosenthal: So that Piccadilly and Ebbw Vale in many ways look rather like... Mottram-in-Longdendale and the area round it. Do you think this is too far-fetched?

Lowry: No, I quite think it must be so, because I’ve painted industrial scenes for very, very many years - about thirty years I should think really - and I got it into my system and I go off to a place like Ebbw Vale and I see Ebbw Vale something like this part. I don’t think it is very different. Piccadilly to me looks, well, rather like any other place. It’s not like parts of London which are very distinctive. I think Piccadilly Circus looking from the angle I took it from looks rather like anywhere else except for the statue of Eros in the middle.

Rosenthal: And this has come out in the painting of course.

Lowry: Yes.

Rosenthal: It’s immediately recognisable as Piccadilly Circus; Eros is there; the red buses are there.

Lowry: Yes. But the figures.

Rosenthal: But the figures. And the whole atmosphere is in fact, for want of a better word, obsessive.

Lowry: Yes, I’m afraid so.

Rosenthal: But to sort of go away for a moment from these standard landscapes: you’ve painted I think a lot of very wonderful seascapes. Do you in fact cover very much of our coast? You’ve picked up the sea and the lakes which you do very well and yet which you don’t show as much as the paintings for which you’re rather better known.

Lowry: Well, I travel about a lot. In fact you may almost say I spend my time now in just travelling in this country - I don’t go abroad. I spend my time in painting and going round seeing my friends... my friends are all scattered in the places I paint and I’m very fond of these places and now... ah well, there’s not much to memorise in a seascape - you just do a seascape. You see it as it’s been a long time. I know the sea pretty well. I’m very fond of it. And the lakes the same angle. The lakes quite a lot. And the lakes not far from here you know, the reservoirs; woodland reservoirs, Manchester Corporation Waterworks. Now they’re very fine, pictorially, you know.

Rosenthal: Which aspect of the Lake District fascinates you more? The water or the mountains?

Lowry: Oh the lake, the blackish sort of lake, like Buttermere, I’d say. It’s the lake really which... I would never think of painting the mountains without the lake.

Rosenthal: You seem, Mr Lowry, to be an artist who is very self-aware. Henry Moore once said when he was asked if he for example read all the Jungian psychoanalytical studies of his work and whether he thought it was a good thing to do so. He said ‘No’, he thought this was a very bad thing because if you become too much self-aware, too much aware of the mental processes which go into your art, eventually you will kill the spark which creates the art. Do you agree with this?

Lowry: Well, I don’t know really. I never have. I just work on my own, apart from what’s said about it. I don’t think I could go in any other way if I wanted to really now. At my time of life I just work as I work. Put it this way: That you start a picture and it takes its own course and you follow like a man in a dream - I don’t really know - yes, you start the picture without knowing where it will end... It always does finish up all right you know... but you don’t know.

Rosenthal: I see that around the studio where we’re sitting now there must be forty or fifty paintings the majority of which are not complete. Do you like to start on one thing and see it all the way through or do you prefer to hop from one canvas to another as the mood takes you?

Lowry: I have to hop from one canvas ’cos I can’t finish them right off. I’ve tried to finish them right off and can’t. They all take a long time. And the strange thing about it is when I think I’ve almost done one right away in the end that takes the longest time to finish. It’s queer that, I’ve often wondered about it.

Rosenthal: In other words you don’t like your work to come easily to you.

Lowry: It doesn’t. It won’t because I want it to. It certainly won’t. It’s very perverse - it won’t do it.

Rosenthal: Actually I used the word canvas. This in fact is rather a misnomer because I suppose, looking round, there’s only one in twenty on canvas. Do you prefer boards?

Lowry: Well, I use canvases for fair sized pictures but for little pictures I like wood. I like wood very much. Or there’s good... excellent substitute for wood now which - these are what we call beaver...

Rosenthal: Hardboard?

Lowry: Hardboard.

Rosenthal: ... board and hardboard and things like that.

Lowry: Very good. For small pictures only. I wouldn’t start a 24 x 20 on a board like that: I’d do it on a canvas - all my larger pictures.

Rosenthal: There’s also an enormous predominance of white on your paintings. Why is that?

Lowry: Can’t help it, it just is.

Rosenthal: It does enable you though to show I think very remarkable skill which is basically an economical one I think. You know you can by means of one or two lines suggest an entire atmosphere, almost an entire human scene. I have a small painting of yours which consists of three small child figures on a dead white background and there’s just one very tiny black line which is just pavement and another smaller shadowy one, vertical one, which gives the effect of a lamp-post, and there you have a complete thing. Can you explain this economy at all?

Lowry: Well, I can tell you how it started. At first when I first did these industrial scenes I did them rather low tone, low key, and they got very low after a short time. And I spent a lot of time on these pictures and I didn’t like it, you see. And so I went lighter. I was advised once to go... paint them very light indeed and I did and I find after a few years they’ve become just right.

Rosenthal: Yes.

Lowry: You see the white drops away... it’s bound to drop. I was advised to do that many, many years ago. ‘That’s no use’ a man said. He was a very knowledgeable gentleman too. He said ‘It’s too dark, look at it, it’s much too dark against the cream wall.’ He said ‘You’ll have to paint that lighter.’ So I thought there’s a lot in it you see but I was cross with him for a while naturally, but afterwards I thought, ‘Well, he’s quite right’ and I painted them white. But I noticed the white was mellow you know. It drops to just right.

Rosenthal: Some people have said - and I can’t help thinking they’re right - that your work has an atmosphere of the 1920s - the figures seem to be twenties-ish - when you do go into paintings that are genuinely depressing in that they show the grim aspects of this depression in the period of the twenties and perhaps of the early thirties you seem somehow to have stuck with this: there’s no sign in your work of what is usually called today ‘the affluent society’; your industrial people still have the sombreness of the people of the twenties. Where in fact today in the industrial North the workers are showing almost as many signs of the affluent society as the workers in the Midlands or the South...

Lowry: Well of course you won’t see a large number of people coming away from a factory... I don’t think they look much better than they used to in the old days. Individually yes - perhaps - but not as a crowd... I think the crowds look just the same. But I just do them as I see them I suppose. I started doing these things in the 1920s ... well my mind still sticks in the 1920s because I do them nearly all from memory. I just do the figures as I saw them, and the houses as I see those too. Some people say they’re less like houses, they’re like little boxes.

Rosenthal: Some people like living in little boxes.

Lowry: That’s right. That’s what I told them but they don’t agree.

Rosenthal: But one thing that struck me is that very rarely it seems that you paint people as people. You don’t often try to show in any way detailed studies of individuals. Is this because you are not interested in people as individuals; you are much more interested in people in the mass, as a whole. Is this a reflection of the basic interest in humanity or what? How would you...

Lowry: Well, I don’t care for portraits: I am not interested in painting a portrait at all. I’ve tried... I’ve only done one person in the last - oh - call it thirty years ago. I like to imagine people, build them up, create my own... well, individuals if you like.

Rosenthal: And yet despite this apparent lack of interest in individuals as such your people come extremely alive.

Lowry: ... Yes, I’m glad to hear you say that. I think they do sometimes, but what I think is nothing: it’s what the other side thinks. Isn’t it really? Do you think?

Rosenthal: Are you sensitive to the opinions of others and do they ever affect your own work?

Lowry: Oh I listen... you get a lot of advice from people, particularly people who don’t paint. Oh very often. Indeed I’ve got a lot of help from young people mostly who don’t paint but are interested. Oh I always listen to what anybody says. I... oh... a young lady, a friend of mine, came in one day and said ‘Look here’ she said ‘this is all very well, you paint in two dimensions all the time.’ So when she’d gone I put in... I altered it of course.

Rosenthal: But did you really alter the picture for the better?

Lowry: Oh yes. The party was quite right: it was flat. I hadn’t noticed it. She was quite right... I told her so: ‘I’ll alter it completely’ I said.

Rosenthal: How interested are you in fact in three-dimensional effect in your painting?

Lowry: Oh, not very much.

Rosenthal: You just find yourself an instinctive painter rather than an intellectual?

Lowry: I think so, yes. I think so, yes. Yes. Definitely.

Rosenthal: Are you very much occupied or preoccupied with the problem of loneliness?

Lowry: No, I am lonely, I live by myself, I’ve got good friends but I’m lonely when I’m by myself, as far as I know. I simply paint as I feel. I suppose I’ve painted a lot of pictures people say are lonely, such as the sea, an odd figure at the sea I paint, I never seem to paint anything on the sea when I paint the sea. And... erh... I either put a lot of people on a landscape or none, people say.

Rosenthal: Do you feel that the figures that you put into your more crowded scenes have any relationship with each other?

Lowry: People say not and I’m inclined to agree with them. Isolated figures, yes.

Rosenthal: Well they are. But I think they’re only isolated in the terribly crowded ones like for example the football match, where they have a very obvious cohesion simply because there are so many of them crammed together. But in fact looking round here your small wood panels there, for example when you have the children playing, the children seem very much together and belong to each other. Is this done deliberately?

Lowry: Oh no it just comes. I’m very glad that you say that. Just comes. Just paint the picture and it comes.

Rosenthal: Do you think that it’s interesting that a painter should be so obsessed with this as you yourself are?

Lowry: I see no reason why a man shouldn’t keep on painting the same thing all his life if he wants to. Because if when he doesn’t want to he’ll change and he probably won’t be able to go back to it.

Rosenthal: A great number of painters, composers, writers, have achieved their greatest work in their seventies, even in their eighties, and sometimes, even in their late seventies they’ve completely changed to something new. Do you think there’s any chance of you doing that?

Lowry: I’ve not noticed it. I... [laughter]... I’m leaving it rather late aren’t I now because I’m in my seventy-fourth year. I’ve changed a little I think but not a lot. What I shall always feel I think is that the industrial scene is my best work.

Rosenthal: Yes. That’s... that’s very true.

Lowry: Is it true do you think?

Rosenthal: Oh completely true.

Lowry: Yes completely.

(end of broadcast transcription)

Lowry serious, as opposed to mischievous, could be wonderfully terse, all part, no doubt, of his quite elaborately constructed public persona. I’m sure that those who think his pictures simple would also characterise his personality in the same way.

That would be foolish. This was an endlessly patient and subtle man who always knew what he was doing, whether personally or in paint. He once (as is fully described by Edwin Mullins), famously applied seven coats of white paint to a piece of cardboard, put it away in a drawer without any light for seven years and, at the end of that time, gave another piece of card its multiple ration of white so that he could compare the effects of time on his favourite colour.

When I asked him about his feeling for the halt, the lame, the down-and-out who so fill his pictures, he said: ‘I feel very interested in them. I have a sympathy for them even if I know there’s nothing I can do for them. I listen to them.’ One of the few discerning critics to admire him in his lifetime, Edwin Mullins, speculated that Lowry was intrigued by these outcasts because he felt himself to be an isolated person.

As for his passion for Rossetti, he said: ‘I’m fascinated by the paintings of his ladies. Nothing else.’

Lowry was much more self-aware than most acquaintances realised, and once observed of those much admired pre-Raphaelite ladies, ‘They are not real women, they are dreams.’

In response to the obvious question about his industrial landscapes, he was both frank and cagey. ‘I see them. I’m interested in them. They’re not beautiful, I know that. I just do them, that’s all. I got obsessed by it, I can’t say why. It just happened.’

His industrial scenes are, in fact, an almost uncannily accurate rendering of something that has no corporeal existence in that form, but is a paradigm of an almost vanished segment of North-West England. While they are wholly imaginary in both concept and composition, the individual components are real, based on his endless perambulations through the area as a rent collector and minor functionary in an estate agent’s office, when he invariably made pencil sketches of buildings and characters who appealed to him.

The last time we met was in September 1966, when I made a long radio feature about him for the Third Programme. It was part re-interview of him and part symposium of the views of various art world dignitaries and fellow painters. My wife and I drove up to a seaside hotel near Sunderland where he was staying (and often used as his North-East base), for which the word modest would be a considerable overstatement.

We had lunch together - a vile meal, even by the standards of the time - and, not too seriously, Lowry maintained that he was a poor man and had been one for forty years. I would have used more than a pinch of salt had I known then what I know now; that via his dealers he had, in 1964, bought at a Christie’s auction Rossetti’s oil portrait of Jane Morris, known as Proserpine, for 5,000 guineas (probably a million pounds today).It became his favourite picture and he bought other pre-Raphaelites - sometimes exchanging them for his own paintings - as well as works by Daumier and the two near-contemporaries he most admired, Lucian Freud and Jacob Epstein. His simple living was no pose. It was part of his character and never conflicted with his massive generosity to others.

I set out below the BBC transcription from the actual broadcast of the symposium transmitted on Saturday 26 November, 1966. This 45-minute programme was compiled and introduced, with appropriate linking passages, by me and was broadcast under the title Every Day in the Week.

Rosenthal: L. S. Lowry is now nearly eighty years old, and while no one could ever have accused him of being an enfant terrible, he is now respectable enough to receive the accolade of an Arts Council retrospective exhibition. Yet he is, in his way, one of the most paradoxical artists England has ever produced. One can look at his paintings for a few seconds and instantly understand them while at the same time they are highly complex works of art. His painting technique also looks, at first glance, crude and unfinished yet is immensely subtle. His choice of subject-matter, the industrial North of England and the stunted factory workers and derelicts whom one still finds there, inspires instant gloom in those who feel that their cocooned home counties existence will be threatened, if not actually sullied, by a trip north of the Trent for anything other than grouse shooting, yet Lowry is in fact a lyrical and poetical recorder of a landscape which has as much intricate visual beauty as the Sussex Downs if one only opens one’s eyes to it. To many who have only seen his occasional excursions onto the television screen and have not come to grips with his paintings, he is a comical old buffer from up north, yet his reluctance to intellectualise about his own work conceals, as usual with the best visual artists, an acute and perceptive mind. In other words, Lowry isn’t half so simple as he appears, and sometimes sounds. For instance, it takes a man of more than average perception to give up painting effective if conventional portraits and competent but derivative Barbizon-type landscapes. Why did Lowry suddenly change the subject-matter of his work?

Lowry: I lived up to 21 years of age on the residential side, and we went to live on the other side for business reasons - a very industrial town called Pendlebury, between Manchester and Bolton. And at first I disliked it intensely... then after quite a year or two I got used to it, and then interested in it and then, and then I got obsessed by it and practically did nothing else for 25 to 30 years.

Rosenthal: Before you moved, had you in fact been painting non-industrial subjects?

Lowry: Painting portraits and landscapes. Just the ordinary portraits and just ordinary landscapes. And that’s all. Little sea pieces and just the ordinary things that most people do. And after going to Pendlebury I did nothing after getting used to the subject-matter in Pendlebury. I did nothing else for 25 or 30 years.

Rosenthal: What made you become obsessed with it?

Lowry: Can’t say. Just happened. It just happened.

Rosenthal: Was it the visual appearance of the factory chimneys and of the factory crowds, or was it in fact what these things meant to you and to other people?

Lowry: No, it was purely pictorial. I looked upon the people as the main feature and the background to the whole thing - the setting.

I asked Lowry if he thought his landscapes were beautiful.

Lowry: Well, I wouldn’t say beautiful. I’d use... I see them and I’m interested and I just do them. That’s all. I don’t... I just see them, do them there, the attraction - something, I can’t quite see what. I do them. It’s really the same way as somebody driving outside and seeing a landscape as I would see, and he draws it and thinks it’s interesting, and that’s what it is.

Rosenthal: Interesting, yes. But, I think, something more than that, and also significant by the mere fact of its being done at all. This is what Herbert Read had to say when I asked him to amplify what he had once said about Lowry’s being a revolutionary.

Read: Perhaps the word revolutionary was rather strong. But he is original in the sense that he has seen the possibilities for painting that exist in the industrial landscape in this country. It’s really quite extraordinary that in an industrial country like this no one... no painter of any significance has ever taken the industrial landscape as a subject, and what you might call industrial art just does not exist. But Lowry had the... well, yes, it’s revolutionary in the sense that he had the new vision of the artistic value of this subject. No one else had seen the industrial landscape as potentially an artistic subject... but naturally there may be behind it some preference of an ideological nature; some preference for the working class as such, for the life of the people as such. That may have guided him towards selection of this particular subject-matter. I don’t know Lowry well enough to know whether that has been a determining influence in his life.

Rosenthal: But he paints, you know, what they call the dark Satanic mills; do you think that he sees them with the same sort of vision as, let us say, Blake?

Read: Well, I don’t think the vision is Satanic in Blake’s sense. Blake was romantic and opposed, I suppose, to the industrial development of England as such. Whereas Lowry, I think, accepts it. To Lowry it is a natural background to his life and thought. I think there is that difference. Therefore I would say that his vision is not Satanic. He accepts the Industrial Revolution and makes the most of it.

I think that sentence about accepting the Industrial Revolution is a key one, since in many ways it exemplifies the differences between North and South in this country, which in turn are reflected in the different attitudes to Lowry. There are those who, quite simply, find Lowry’s paintings ugly; others find beauty in them. Beauty is still of course very much a matter of the eye of the beholder, and this applies as much to the industrial North itself as to the paintings of it. This is how John Rothenstein reconciles the paradox.

Rothenstein: I think he’s done one very important thing historically. I think the whole history of modern art... has been the history of expansion with the concept of beauty, that is to say in times of Classical Greece very few things were thought beautiful and in modern times artists have taken more and more things and beautified them, presented them to the world in terms of poetic beauty, and Lowry has taken, if the inhabitants will forgive my saying so, one of the dreariest regions, visually speaking, of the whole civilised world, and presented it in terms of an extremely moving poetry, and therefore by doing so he’s expanded our whole conception of what is beautiful and what may be beautiful.

In its triumph over what ought, in theory, to be bleak and grim, the beauty that Lowry imposes is, almost literally, transcendental, although Herbert Read finds that the relative beauty of subject and treatment are somehow integral and intrinsic.

Read: Well, anyone who has had any experience of this industrial landscape does feel its poetry. I myself - in my youth - was familiar with the industrial landscape round Leeds, and very much moved by its subtleties of form and colour. The outlines of the West Yorkshire mills and their chimneys and so on often have very great formal beauty. And then there is this atmosphere which is created by the smoke and fog and so on, but can be a great beauty from an atmospheric point of view, from a colour point of view. If one learns to see things, as it were to disassociate the form and atmosphere from the function, then one sees that it has beauty and that this beauty can be conveyed in painting. That industrial landscape, as it were, becomes an equivalent to the romantic landscapes of, shall we say, Corot?

Rosenthal: You’ve also observed Lowry’s fidelity to this Northern industrial landscape. Do you think that Lowry could in fact have been as good a painter as he is if he had not been born in this environment and if he had not in fact devoted the majority of his painting career to that environment?

Read: No, I doubt if he would have developed in the same way or become the same kind of artist in a different environment. I think that the industrial landscape found its poet as it were, its artist, in Lowry, and that he had a particular kind of sensibility which saw the possibilities in that landscape. He has, of course, formal qualities which are universal. He has not only a sense of form and composition, but a personal colour sense, personal feeling for harmony of various kinds, which might have been transposed into other subject-matter. [My guess is that he would not have been inspired by different kinds of landscape.]

As a matter of fact Lowry has also done a large number of seascapes, some of which are entirely successful as paintings, but I can’t help seeing some significance both in Herbert Read’s last remark and in the fact that Lowry has turned more to the sea in the last few years when he has, at least partly, abandoned the industrial scene in order to paint a lot of seascapes recently.

Lowry: I like to do seascapes. I’m very fond, now and then, of doing beach scenes. But the fact is that after getting used to the industrial scene, I never painted... and a friend of mine thinks I might have started painting the sea later on in life and it probably would have happened, I should say.

Rosenthal: Well, you have in fact painted a lot of seascapes?

Lowry: Quite a number, but not what you’d call a lot. Every so often I like to do them, and what interests me here is of course the shipping on the sea and the rivers and the sea itself.

Rosenthal: What is it about the sea that attracts you as a painter?

Lowry: The vastness of it and the wonderful different conditions on it. It’s changing all the time. Anything’s possible... you can hear it strumming over the promenade. It was a wonderful sight, but it was very fearsome to my way of thinking, particularly the east coast far more than the west.

In a sense the sea has been an escape for Lowry from the industrialism that has haunted him, but it’s not a very far-reaching escape; Lowry has now adopted the sea at Roker on the coast by Sunderland, a move which John Rothenstein saw as being eminently logical.

Rothenstein: Well, he happened to be lunching with me one day, and he was talking about the North-East coast and he said, I’m thinking of settling there, so I said to him, I suppose you think you’ve discovered a place that’s even more forbidding than Salford, and there was a long silence and he said, I think that’s just about it.

Actually, however forbidding the town of Sunderland may be, the sea at Roker can be magnificent, and indeed was just that when I visited Lowry and recorded these conversations with him in his regular first-floor room in a hotel overlooking the water.

Lowry: The sea, well I like the sea for its own sake. I’m very fond of the sea... oh yes, I’m very fond of the sea.

But while he’s fond of it, he also finds it terrible, and I asked him why.

Lowry: Well, it comes in, comes in and comes in. There it is, this vast expanse, and I often wonder and often say to friends, I wonder wouldn’t it be dreadful... what would happen if the sea suddenly didn’t... the tide didn’t turn and the sea came on and on and on and on and on. What would it be like? Wouldn’t it be wonderful just to see it? Just fancy... on and on and on... didn’t stop at all. Went on forever. Awful, isn’t it? And I often think too that these people reckon that the tide will come in and are waiting outside with the ships that are going to come in with the tide in Newcastle on the Tyne, and I often wonder what would happen if the tide didn’t come in and went somewhere else. If the tide did come in I don’t know what it is that keeps it so... but it’s a dreadful thing, it can be dreadful... at times, you know. Have you been on the sea... do you feel the same thing? It’s all around you...

I think that some of this obsessional attitude towards the sea is reflected in the paintings themselves. His seas are neither conventionally placid nor typically tempestuous. Instead they are simultaneously both the subject and the object of a quiet intensity which is reflected in the concentration on a virtually monochromatic scale of grey and white. In this they become more concentrated versions of his industrial skies, and I think it’s worth looking at his handling of paint from the point of view of other painters... Josef Herman, who has a high regard for Lowry, has shared an exhibition with him. I asked him whether he didn’t find Lowry’s technique to a certain extent uninteresting and unsensual.

Herman: I don’t agree that the technique is uninteresting, but what I do agree with is there are no sensual qualities to it. But this was to my mind a deliberate choice in technique. The paste-like quality of his whites, or the blacks, they achieve a certain plasticity without going into the research of itself... Lowry does not explore but what he uses are colours which struck him as true to life, and because he lived in an industrial area and because the subject-matter is of this area, naturally the restricted palette is a truer expression of this.

Rosenthal: And what about when he moves away from the industrial area? When he does his seascapes, some of which are very beautiful indeed?

Herman: Yes, this is perfectly true, but in painting, if once you acquire a technique, and once you acquire a style, you use it in whatever subject you will tackle, you see, and therefore between his seascapes and his cityscapes there exists no difference either in technique or style.

Michael Ayrton also approves of Lowry’s technique:

Ayrton: I think it was inspired in him to limit his range to the extent that he has done. As a technician I would have thought he was comparatively rudimentary, but needs to be nothing else.

Inevitably, I suppose, when you talk about Lowry’s technique you come up against the question of whether or not he is a naïve or primitive painter. The borderline between a painter like Lowry and the obvious primitives like Bauchant or Bombois is probably just as clear as that between Lowry and the obviously bad Sunday painters like Grandma Moses. But having said that, it’s far harder clearly to define where Lowry stands in relationship to them and primitive art in general. This is what Herbert Read says:

Read: I don’t think he is naïve in the strict sense of the word. I mean, I’ve met Mr Lowry and talked to him. I’ve seen the film that my son made of him, where he spoke a great deal about his life and ideals. I don’t think he is naïve in the proper sense of the word. But, well, I search for the right kind of word to describe him, I think he is a simple man in a certain sense of that word. He lives a simple life, and although that in itself might be a pose, I don’t think it is. I think he has a genuine preference for the simple life, and that this is part of his character which determines the nature of his painting.

Professor E. H. Gombrich also fails to see anything of the primitive in Lowry:

Gombrich: From the point of view of his very subtle gradation of tone and his very great awareness of tonal values, he is certainly not a primitive painter in the same sense in which, let us say, Grandma Moses is a primitive painter.

And this is how Edwin Mullins, who did the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition, sees him:

Mullins: In terms of the way he paints, he is anything but naïve; a lot of people think of Lowry as a very simple, almost primitive painter I think it very important to stress that in the way he actually applies his paint, in the interest he has in the texture and colour of paint, he has an entirely professional approach. There’s that story which he has often told of how be became interested in the colour white. How he painted one board, one piece of card, with several coats of white paint, and then locked this card away so that air couldn’t get to it, just as though it were in fact under glass, for seven years, and then before he took it out he painted another card with exactly the same white, and then unlocked the other one, and compared the two, and as a result of comparing the two he realised what he wanted to obtain from the texture of white. Now, this is immensely scientific and sophisticated and very much the reverse of a naïve approach to painting. And Lowry to me is a master of his particular way of using paint, particularly, of course, monochrome painting. He’s not, to my mind, a colourist as such. His colours emerge from colourlessness, from black, from grey, from white, from slight tints of white; he’s a master at being able to produce eight or nine different colours out of white, another eight or nine out of black, and give the appearance of a multicoloured canvas, where in fact colour does not exist. This I think is an important contribution that he’s made, even if it isn’t a contribution which other painters may learn from. But don’t get the impression - I hope no one does get the impression - that he is a simpleton. He’s very far from that.

Rosenthal: Indeed he is. You only have to look at his human figures to see that. Next to factory chimneys and dark streets the images conjured up by the name Lowry are most often those of people, either eccentric individuals or crowds of rushing homunculi, faintly Chaplinesque, slightly pathetic, sometimes compassionately observed, sometimes seen and depicted with a slightly sardonic humour. Lowry is fascinated by society’s rejects and accepts his fascination as a matter of course.

Lowry: I just do them for the same reason as some people paint a still-life or a landscape or anything else. But these last years, I’ve been doing quite a number of down-and-outs, you call them. I really feel very interested in them. And I feel a sort of, well, I have a sympathy for them. You can’t do anything for them, you know. There they are, looking into space, you’ve done all this scene, they’ll be standing there suffering, might be standing... as far as I know. And you can’t do anything about it. It’s too late. I might want to chat with some of them. Got a lot to say - you know, very nice people. And until you get on to their private life. One man I remember quite well - be was very, very nice, and he was in a park, and he said, ‘Can you spare tuppence for me, guvnor, for a cup of tea? I haven’t had anything to eat or drink for ooh, two days.’ I said, I’ll give you two pence with pleasure, but when you’ve told me you’ve had nothing for two days, I don’t believe you... what the dickens you like. And he laughed heartily and we got talking, got in conversation. Well, and then I saw him by strange chance in another park about a fortnight after and we like... started chattering again, you know. And he talked a great deal about himself. So much so as to encourage me to ask him what had happened to him, of course - he said, and he dried up, and he didn’t say a word. Ten minutes went by, and I said good afternoon to him and he didn’t say a word. He closed up just like that.

One can see why these people fascinate him from a visual point of view, and Edwin Mullins has this explanation for their actual fascination:

Mullins: This contrast between extreme loneliness and a concern with a bustling, teeming human life, like an ant-hill, gives you I think the two opposite poles of his way of looking at the world, and they are very much part of his own particular feelings perhaps about the society in which he lives. I think it’s very important that Lowry is a man who has never felt himself to belong in any way to the world around him. He has an entirely detached attitude to life as it is lived, and the way he paints is almost like someone looking at our world from another world. I think that the figures he draws, these caricatures that he’s done increasingly with old age, have a frightening detachment which, at the same time, as he presents his figures, in a detached way, they manage to reflect his own personal mood, his own loneliness, his own feelings that life has rather passed him by. This is a very curious combination of subjectivity and feelings of really having no pity, no love, no hate, no concern at all for the wellbeing of other people; he looks upon people with a kind of fascinated curiosity. He’s interested in outcasts, partly because he himself feels himself to be an isolated person, but also because he thinks they’re so very funny. Now only a man with this frightening degree of detachment could present the grotesque in other people with this almost coldness. I find this aspect of Lowry very frightening and very, very powerful. I can’t imagine a committed human being, a human being who loved others, was involved in others, who had lived, one is tempted to say lived a normal married life, Lowry has never married, he has very few friends, one can’t imagine a person, other than Lowry, being able to present people in quite this ruthless way.

Is Lowry detached and ruthless and lonely? Perhaps he’s all these things, and they are reflected in his figures. Yet all these qualities are at variance with the gentleness of his personality, which, as Herbert Read said, isn’t a pose. He is generous to other artists and buys their work, notably that of Sheila Fell, but I wonder whether it isn’t significant that among earlier artists he really only likes the Victorians, whose painting, for all its sentimentality, remained curiously unemotional. Lowry has several Rossetti drawings in his house, and I asked him why he liked Rossetti:

Lowry: ... fascinated by the paintings of his ladies. Nothing else. Not his subject pictures. Do you ever... what it is that attracts me, I don’t know. That’s all it is. He’s the only man who I’ve ever really seriously... I shall keep on collecting Rossettis. I like some of the others. I’m very fond, you know, very interested in Victorian art. I don’t mean it’s very great art, particularly nowadays, I think so... I like it more than ever. I like all of them. I like the place. I like the lot. In a sense. Rossetti is the only one I ever wanted to possess, and I’ve got some very good ones, I think, and I’d like to have some more some time.

Yet there could be few painters more different from Lowry than the precise, almost clinical Rossetti. Lowry’s art is much more diffuse, much more the result of imagination given a forward push by a couple of pinches of reality. As Edwin Mullins says:

Mullins: Lowry, in fact, very rarely records literally what he has seen. A great number of his compositions, I should say probably the majority of his compositions, are made up from a host of different impressions that his memory has stored up. He will build up a canvas starting from, he doesn’t know what. He’s told me that he’s often started with a seascape and, in the course of working through the night very often, it has become a mill-scene, or a mill-scene has become a landscape, or an empty landscape with lakes has become a composition full of little bustling figures... the point of this is, I think, that he’s to a very great extent a subjective painter. He’s not an objective recorder of something seen. And to me the impact of a Lowry is very largely that one is made aware of the personal feelings of Lowry. He’s recording as it were the scene from within him, not just what the eyes see.

I think that that in many ways is the key to Lowry’s art. Neither wholly imaginative nor wholly recording, it’s an interpretation of people and places around him, as seen through his highly personal, jaundice-coloured spectacles, and it is this that makes him so hard to classify or place in the history of English, let alone European, painting. Michael Ayrton has an interesting point of view:

Ayrton: I should have thought the English Utrillo is probably the place I should describe Lowry as fitting. I think the point about Utrillo is that his quality, which at the moment is rather out of fashion, is a sense of the ambience of Paris, the quality of the plaster walls, the quality of the rooftops, of the quality of the city itself. The figures in Utrillo’s paintings, which were not as well drawn as those in Lowry’s, always seem too haphazard, and not in fact to be the centre of the situation. Nevertheless, they inhabit the place, and Lowry, like Utrillo, paints inhabited places. He is to me a city painter; he’s an English city painter, whereas Utrillo is essentially the city of Paris painter, of the early twenties - the early part of the twentieth century. I’ve always thought of them together, though when I first encountered Lowry’s work, Utrillo was a kind of highly prized myth who drank himself to death and was drinking himself to death, and all sorts of glamorous things like that, while Lowry seemed infinitely more English, infinitely more down-to-earth, and infinitely less likely to indulge in any of the bohemian chi-chi which attaches to the legend of Utrillo. Nevertheless, there is, I think, a common chord there. A sense of place, and of urban place, in a specific kind of way, and both have the quality of the self-taught. It’s not the same as primitiveness, but it is self-taught.

Self-taught but not primitive. I asked Professor Gombrich whether there were any links between Lowry and Europeans like Douanier Rousseau, at least in terms of imagery:

Gombrich: Yes, there may be some links in the way in which he isolates individual figures, in which he keeps his painting very legible, in that sense, perhaps like a children’s drawing, but this is only the scaffolding as it were for a very subtle distribution of shapes and forms.

And this is how Herbert Read sees Lowry against the background of twentieth-century English painting:

Read: I think he’s a lone wolf in the sense that he is not particularly interested in the main trends or movements of contemporary art, and doesn’t fit very naturally into them. But there are always in any period lone wolves who stand out from the mainstream, who stand apart from the crowd. They have their place in the contemporary scene. They are, let us say, influenced by the same factors perhaps that influence and create the typical movements of a period. But for some reason, some sense of independence, or sense of isolation, they decide to go their own way and to paint in their own way. And they can be some of the most typical artists of their period. One only thinks back to examples like William Blake at the beginning of the nineteenth century. He occupied a similar kind of isolated position in English painting, and yet when we look back over 150 years or so, we see that he did belong to the period, was part of the romantic movement, and I think 150 years hence Lowry will be seen to be part of the general trend of modern art. But that is not the same thing as belonging to a specific movement.

That Lowry is a lone wolf is undeniable, but I wonder if Lowry has ever been influenced by any other painter or whether in turn he has himself exerted an influence? Michael Ayrton does trace some influences, but of an indirect kind:

Ayrton: I would be very hard put to it to know who has influenced Lowry. Oddly enough, I detect a faint influence of a long-forgotten artist, Ethel Walker. Particularly in his painting of the sea, but this may be pure fantasy on my part. I think Lowry belongs to an English tradition which is essentially a provincial tradition containing such artists as Joseph Wright of Derby, for instance, but I very much doubt if there’s any direct connection. I strongly suspect that like many self-taught painters, though there is influence, it is unconscious, and though there is derivation, it is taken in as influence often is by self-taught painters in a complete unconscious and unaware fashion.[1] I don’t see any direct derivation from Lowry. In terms of his influence, I would have thought that he had influenced painters like George Chapman, I would have thought even, perhaps, Josef Herman owed something to Lowry. It’s very much a specific English topographical tradition he belongs to. And this is by no means a very fashionable form of expression now. But I have a strong suspicion that it’s quite a permanent one.

Lowry was certainly unfashionable, yet as for other unfashionable figures before him, the tide has turned, and few English artists are more popular today. Perhaps in this he is wholly English traditional, out on a limb and at the same time accepted in the end as part of the common body. Does he perhaps after all belong to the loosely knit English tradition? That’s not quite the way Edwin Mullins sees it:

Mullins: I think he clearly doesn’t. He doesn’t belong to anybody, you can’t place him alongside any other English painter, and say he owes this, that and the other to him. In the early paintings you can see something of the influence of Whistler, something of the influence of English Impressionism, but this is a very fleeting influence. The moment he acquires his own style of presenting figures all influences really vanish. But I do think at the same time that he belongs to a different kind of tradition, which is that of the English isolated eccentric who’s gone his own way, and one would mention artists like Richard Dadd, Blake is an obvious example, Stanley Spencer a more recent example, who may have nothing in common between them, except that they are all isolated freaks. One hates to call Lowry a freak because no one as a human being is less of a freak, but what they contribute to art is nonetheless freakish by its being so totally isolated from its surroundings. This seems to be a particularly English contribution to art. I can’t define it, I can’t even pretend to explain why it should happen. There must be something about English life which is particularly conducive to this sort of art, and I think it’s a very valuable part of the English artistic tradition.

And what does Lowry himself think about his work? I asked him if he thought it was naïve:

Lowry: Well, I don’t think they are. I drew the life, but I - well, put it this way, when I started to try to create the industrial scene, I did a lot of little figures and little drawings, sketches, and they looked like they do look, you know what I mean. And I thought, well, it’s got to be, so there we are. That’s all. If I’d painted a portrait from life, well, I don’t know... as I don’t do any paintings from life, I just don’t know what’s happened. I don’t know. But if they all thought of things about me... well, and sometimes I laugh, and say just fancy that! I can’t think whether they’re naïve or not. I don’t intend them - I do them as well as I can, to express what I want.

Rosenthal: How much formal training did you have, and how much did it stick with you?

Lowry: Well, the training lasted me all my life, really. I did the anatomy, and I did a very useful - I draw the figures as well as I need to draw them. As well as I can draw them in a way to suit my purpose. But an ordinary live figure... that would bore me to death. You see, I don’t want to do it. You can’t photograph these mill scenes. Can’t do that. They’re too - you’ve got to be personal about it. Of course, I thought everybody else would really see it redundant, I did one when I started doing them, now I said to myself, I don’t think anybody’s ever done this mill scene business - as far as I can see Stanley Houghton wrote about it a little, as writing it, the Hindle Wakes man, you know Hindle Wakes - he was very good, I was very interested in him. And I started idly to do them, and then I said to myself if I can just get these things established, probably I’d clear out. Because I didn’t intend to paint all my life, you know. I only expected to get out about 1948, but by then I’d mixed up in it and couldn’t stop. But the last five years I’d been very fed up with it. I’d wanted to stop.

Rosenthal: Do you find beauty in paint itself?

Lowry: Well, if I could press a button, and have it done, I’d like to do that, you know. No - it’s all the job, an income sort of job - painting, but it’s got to be done, and you do it as well as you can, always as well as you can. If I could press a button and have it done, of course, I’d like to do that. I’m not one for painting for painting’s sake. But, as I say, if I could press a button I’d like to do it, you know. I’d save myself the trouble.

Lowry likes phrases like that. He told us over lunch that he was tired, and, after a suitable pause, that he’d been tired now for forty years. In fact, it’s all too easy to see Lowry as an eccentric from both a human and an artistic point of view, easy since that basically is what he is. But it is in many ways a calculated eccentricity, which only partially hides the man underneath and hardly hides at all the very considerable painter that he is. Lowry stands apart in more than the lone wolf sense. He is, as Professor Gombrich says, wholly individual:

Gombrich: I feel very much that what distinguishes Lowry and makes his contribution particularly precious at this time is that he never tries to follow a fashion; he did not try to be original, he just was original. And he never tried, as far as I am aware, to be ahead of his time, or to follow a new trend, to jump on any bandwagon; he just was himself. And in this way he became an individual and great artist.

A Lancashire Town, 1945, oil on canvas, 54.6 x 64.8 cm.

A great artist. In his way Lowry is that. He has made the harsh landscape of the industrial North take on the beauty which was its ravaged birthright. He has taken the scurrying crowds of the mill towns and turned them into individual streams of the life force and, when his sardonic eye has settled on some wretched derelict or down-and-out, he has extracted from him not only the obvious pathos, but also a kind of triumphant humour entirely lacking in self-pity. Modern art and its presentation always raises a great deal of dust, but Lowry’s has for a number of reasons, mostly connected with his relatively late discovery and the unfashionableness of his work, raised no dust at all, so that one can already see him with a fair amount of clarity and detachment. I think that in fifty years’ time, when all the dust around him has settled, the work of L. S. Lowry will be seen as some of the most original and some of the finest English art of the 20th century.[2] But if that’s too solemn a thought, perhaps we should let Lowry have the last word - provided that we remember that neither the work nor the man is nearly as simple as he’d have us believe.

Lowry: People call me a Sunday painter, well I suppose I’m a Sunday painter who paints every day in the week.

1 It was assumed well into the 1960s and before the first appearance of Shelley Rohde’s biography in 1979 that Lowry had had no formal art education. It is perhaps interesting to note that Michael Ayrton himself was a virtually self-taught painter and sculptor.

2 At the time of publication of this book that fifty years will almost have elapsed. It is up to the reader to decide whether that prognostication by a then relatively youthful writer on art has proved valid.