When the first edition of this book appeared, readers told me how struck they were by the very first example. It wasn’t a famous game. Far from it. But there was something about the way it unfolded:

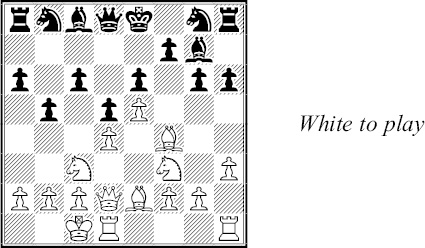

Klyavin – Zhdanov, Latvian Championship 1961

1 e4 c6 2 ♘c3 d5 3 ♘f3 g6 4 d4 ♗g7 5 h3 a6 6 ♗f4 ♘f6? 7 e5 ♘g8 8 ♕d2 b5 9 ♗e2 h6 10 0-0-0 e6

It didn’t take readers long to conclude that White has a very strong position. He has brought out nearly all of his pieces while Black’s only developed piece, his KB, ‘bites on granite’ at e5. Black’s queenside is riddled with holes on dark squares and he has just locked in his other bishop. You might expect a quick mating attack. You would be right:

11 g4 ♘d7 12 ♗g3 ♗f8! 13 ♖df1 ♘b6 14 ♘d1 a5 15 ♘e1 b4 16 ♘d3 ♘c4 17 ♕e1 ♕b6 18 b3 ♕xd4! 19 bxc4 ♕a1+ 20 ♔d2 dxc4 21 ♘f4 ♕xa2 22 ♔e3!? ♗b7 23 ♕d2 g5 24 ♘h5 c3 25 ♕d3 ♖d8 26 ♕e4 ♗c5+ 27 ♔f3 ♖d4 28 ♕e3 ♕d5+ and mates

Yes, Black delivered the mate. Actually, with a good understanding of defensive play the game’s result should not be at all surprising to you. But that understanding is the most difficult chess knowledge to acquire.

And it is worth acquiring. It should be no surprise that great players are great defenders. When Garry Kasparov was asked during his great rivalry with Anatoly Karpov why they dominated chess he replied, “We attack better than anyone else – and we defend better than anyone else.”

Before we get into specific techniques and approaches to defense, let’s dispose of some myths. What is defense, really?

Defense is dull.

How defense got a reputation as plodding and boring is a mystery. Good defense is intensely tactical. It is perhaps 90 percent tactics – and in some positions, more. The defender must rely more on tactics than his opponent does.

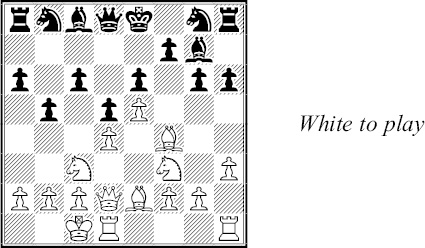

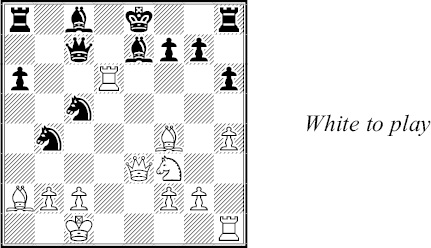

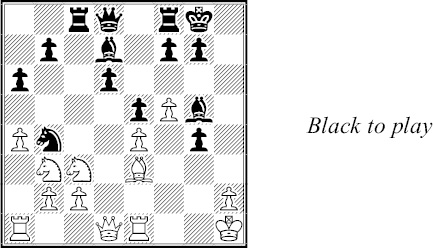

Schneider – Benjamin, U.S. Chess League 2013

1 e4 e5 2 ♘f3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 ♕xd4 a6 5 ♗g5 ♘c6 6 ♕d2 ♗e7 7 h4 ♘f6 8 ♘c3 h6 9 ♗f4 b5 10 0-0-0!? b4! 11 ♘d5 ♘xe4 12 ♕e3 ♘c5

Aron Nimzovich, a great defender, warned against pawn grabbing in the opening. But he made an exception for swiping a center pawn. Here Black spent two tempi to win the e4-pawn. He is ready to beat back a White initiative with simple moves such as ... ♗e6, ... ♘e6 or ... ♗g4.

White felt he had to strike now with 13 ♘xc7+ ♕xc7. However, the natural 14 ♗xd6 fails to 14 ... ♕a7!, when everything is protected and he will be able to consolidate with 15 ... ♘e6.

Instead, White chose 14 ♖xd6!, which threatened 15 ♕xc5 and 15 ♖xh6! (15 ... ♖xh6 16 ♗xc7).

Traditional defensive thinking stressed the importance of parrying immediate threats. Well, of course, that is important. But if parrying threats were all that mattered, Black would look no further than 14 ... ♕b6.

And he would have had his work cut out for him after 15 ♗c4 followed by ♘d4 and ♖e1.

Instead, Black began a counter-attack, seeking mate no less, with 14 ... b3!!. He can answer 15 ♖xh6 with 15 ... ♖xh6 16 ♗xc7 bxa2! and replace the lost queen with a new one (17 ♕a3 ♘d3+!).

Traditional defensive thinking would say White’s chief responsibility is to find a way to stop ... bxa2. But on 15 axb3 Black would continue to counterattack with 15 ... ♘b4! and 16 ... ♕a5. In fact, 15 a3 would also be met by 15 ... ♘b4! because 16 axb4 ♘e6! would threaten mate on c2 as well as 17 ... ♗xd6 and 17 ... ♘xf4.

Instead, White found a move that both attacks and defends, 15 ♗c4, and there followed 15 ... bxa2 16 ♗xa2 ♘b4.

Black threatens 17 ... ♘xa2+, of course. But the more dangerous idea is 17 ... ♘cd3+! and mate around c2.

The surprises kept coming. White found 17 ♗xf7+!, based on 17 ... ♔xf7 18 ♖f6+ and ♗xc7.

Black replied 17 ... ♔f8 and on 18 ♗g6 he was finally able to take the rook, 18 ... ♘cd3+! 19 ♗xd3 ♗xd6 20 ♗xd6+ ♕xd6.

With only two pawns for a rook, the game must be over, right? Well, that was a common attitude many years ago. Now we know it’s usually a dangerous way for a defender to think. White found new ways to exploit Black’s king position, 21 ♗e4 ♖b8 22 ♘d4 ♔f7 23 ♖e1 and then 23 ... ♖d8 24 ♕b3+ ♔f8 25 ♖e3, preparing ♖f3+.

Black blocked, 25 ... ♘d5! 26 ♖f3+ ♘f6, and walked through the final flurry of checks, 27 ♖xf6+ gxf6 28 ♕e3 ♕xd4! 29 ♕xh6+ ♔e7 30 ♕g7+ ♔d6 31 ♕g3+ ♕e5 32 ♕d3+ ♔e7 33 ♕a3+ ♕d6 White resigns.

So, defense is not at all dull. But there are other myths to debunk:

Defense is one-dimensional.

The charge that defensive play is mechanical, unimaginative and with little room for variety is also unfounded.

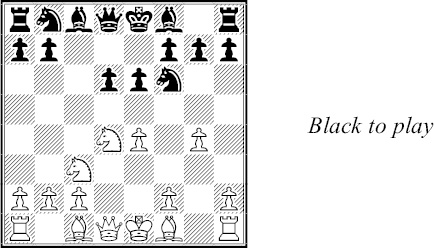

This is a position from a popular Sicilian Defense variation, the Keres Attack, that begins 1 e4 c5 2 ♘f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 ♘xd4 ♘f6 5 ♘c3 e6 6 g4. White’s intent is no secret: he seeks a pawn storm with g4-g5, followed perhaps by h2-h4-h5 and g5-g6 to open lines around Black’s king.

Black’s biggest problem is that he has too many ways to try to defend:

He can try to strike in the center with 6 ... d5 or 6 ... e5. This is a traditional policy. But there are tactical problems after 6 ... d5 7 exd5, e.g. 7 ... exd5 8 g5 ♘e4 9 ♕e2 or 7 ... ♘xd5 8 ♗b5+! ♗d7 9 ♘xd5 exd5 10 ♕e2+! ♕e7 11 ♗e3 and Black’s disorganized pieces face a dangerous initiative.

Another natural policy is to trade pieces. But again that’s faulty here, e.g. 6 ... ♘c6 7 g5 ♘xd4? 8 ♕xd4 ♘d7 9 ♗e3 leaves White with dominating control of the center.

More promising are the strategies that take the sting out of g4-g5 with 6 ... h6 or counterattack with 6 ... a6 and ... b5-b4. But 6 ... h6 ensures that kingside lines will be opened after g4-g5/... hxg5 and a recapture on g5. And 6 ... a6 is slow. Black can even anticipate White’s advance with 6 ... ♘fd7 and ... ♘b6 – but that’s even slower.

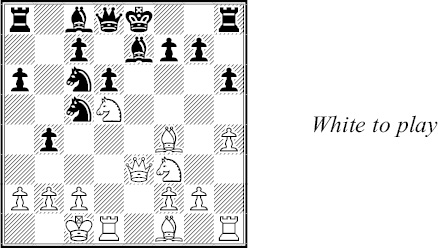

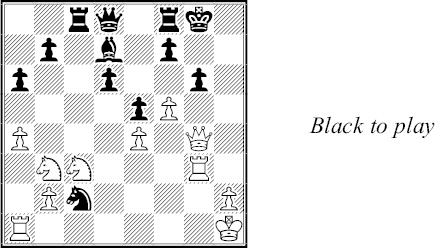

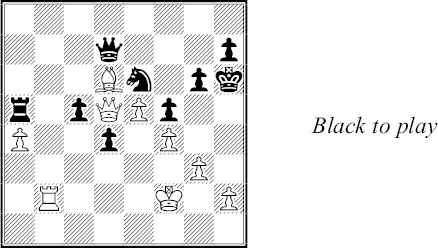

Let’s see how this kind of choice works in a middlegame position.

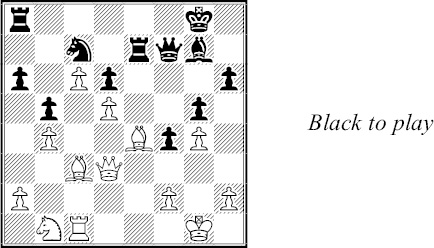

Once again White is shooting for a quick g4-g5. Classical thinking said an attack like this should be answered by a strike in the center, 1 ... d5. But here there is little compensation after 2 exd5 e4 and simply 3 ♗g2.

A second approach is to anticipate White, with what we call prophylaxis. Black can retreat immediately with 1 ... ♘e8. His aim is to play 2 ... ♗g5!, seize control of key kingside squares and offer a piece trade.

But White can play 2 ♕d2!. That stops ... ♗g5 and prepares a protected push of his g-pawn. A more successful version of that idea is 1 ... h6 followed by ... ♘h7 and perhaps ... ♘g5. That is stodgy but solid.

Black chose the most ambitious alternative, 1 ... h5!. This is characteristic of New Defense thinking: Confront, confound, confuse.

If White tries to maintain his pawn at g4, with 2 h3 hxg4 3 hxg4, Black could employ a better version of the 3 ... ♘h7! idea.

And on 2 gxh5 Black has a superior version of the center strike idea, 2 ... d5!. Then on 3 exd5 ♗xf5 the attack is blunted and Black will regain his pawn by taking on c2 (or on d5 after 4 ... e4).

But the real key to Black’s play was revealed when he met White’s reply, 2 g5, with 2 ... ♘g4! 3 ♗xg4 ♗xg5!. This works because the tactics, 4 ♗xg5 ♕xg5 and ... ♕xg4+, would favor him.

White found the superior 4 ♖e1 hxg4 5 ♔h1. He prepares to use the halfopen g-file. But more important, he safeguards his king from tactics on the g1-a7 diagonal. (Compare this with 5 ♕xg4 ♗xe3+ 6 ♖xe3 ♕b6! 7 ♖ae1 ♖xc3! 8 bxc3 ♘xc2.)

With 1 ... h5 Black overturned traditional defensive thinking, which said that you should not voluntarily advance the pawns in front of your castled king.

He further violated it with 5 ... g6!. This makes sense because 6 fxg6 fxg6 would give him greater kingside control than White.

White accepted the challenge with 6 ♕xg4! and then 6 ... ♗xe3 7 ♖xe3 ♘xc2 8 ♖g3!. When an attacker’s pieces outnumber the defender’s in a target area – like the kingside here – favorable tactics are likely, if not inevitable.

For example 8 ... ♘xa1? 9 ♕h5 threatens a quick mate after fxg6 or ♕h6. Key lines are 9 ... ♗e8 10 ♕h6! followed by ♖h3 and 9 ... ♕f6 10 ♘d5 ♕h8 11 ♘e7+ ♔g7 12 ♖xg6+!.

But the philosophy of New Defense says White is not the only player entitled to sacrifice. Black battled back with 8 ... ♖xc3! and then 9 bxc3 ♘xa1. The attack would be over and Black would have all the winning chances after 10 ♘xa1 ♕f6.

White had one last bullet to fire, 10 ♕h5!. But Black replied 10 ... ♗e8! so he could meet 11 ♕h6 and 12 ♖h3 with 11 ... ♕f6 and ... ♕g7.

The sparkling game ended in perpetual check after 11 fxg6 fxg6 12 ♖xg6+! ♗xg6 13 ♕xg6+.

Good defense can mean finding a single, good tactical shot. But more often it requires ten or more moves of hard work. When your opponent has several positional advantages he may be able to press you and press you. Finding one great defensive move won’t be enough to save you.

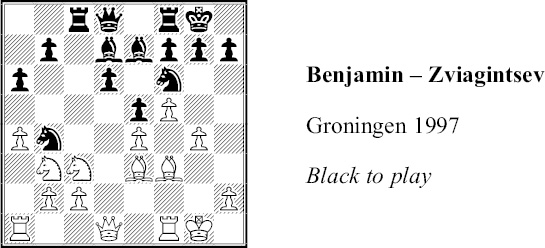

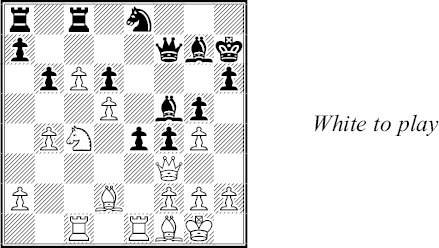

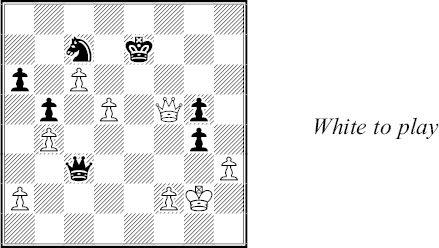

White has a dominating bishop and what appears to be decisive pressure against the queenside pawns (1 ... ♖b6 2 a5 or 1 ... ♘d8? 2 e6+! ♕g7 3 ♗e5).

But Black had sought this position because of 1 ... a5!. Then 2 ♕xc6 ♕xc6 3 ♖xc6 axb4 and 4 ♗xb4 ♖xb4 5 ♖xe6 ♖axa4 would liquidate into a very drawish endgame.

But 1 ... a5 just met the first crisis. White created a new one with 2 bxa5! and then 2 ... c5! 3 ♕f3!– not 3 ♗xc5? ♖c7 4 ♕b4 ♖ab7 or 4 ♕e3 d4.

After 3 ... d4 he could not hold his extra pawn. But he got good heavy piece play by means of 4 ♖b3! ♖xb3 5 ♕xb3 ♖xa5 6 ♖b1.

This is what a good aggressive player does when his initiative is waning: He converts his positional or material advantage into something equally good. Now instead of pressure against mere pawns White is aiming higher, with ♕d5 or ♕b8+ (6 ... ♖xa4? 7 ♕b8+ ♔g7 8 ♖b7 or 7 ... ♘d8 8 e6).

Black needed to pass more tests and did it with 6 ... ♔g7 7 ♕d5 ♔h6!. With his king secure he can fight back against 8 ♖b7 with 8 ... ♕xa4 and ... ♕d1+.

White secured his own king’s safety with 8 ♔g2 and then 8 ... ♕f7 9 ♔f2 (to stop ... ♘xf4+).

Black appeared to be close to running out of moves after 9 ... ♕d7 10 ♖b2! in view of 10 ... ♖a7 11 a5 and 12 a6.

But Black wasn’t done. He found 10 ... ♖xa4! 11 ♖b7 ♖a2+!.

This works because 12 ♕xa2 ♕xb7 13 ♕xe6 ♕b2+ leads to the same kind of perpetual check we saw earlier (14 ♔g1 ♕c1+ 15 ♔g2 ♕d2+ 16 ♔h3 ♕e2!). And 12 ♔e1, for example, risks losing after 12 ... ♕a4!.

The hard work demanded of defenders leads to another myth:

Defense is unrewarding.

Amateurs often complain that even if they manage to meet all of their opponent’s threats the best that they can hope for is a draw.

Of course, that’s better than losing. But it seems to many players that the defender puts in a lot of work at the board for a minimum return.

Actually, defense often pays off handsomely because it is harder to defend. The attacker may have an easy time picking from among the forcing moves at his disposal. The more alert defender can upset the lazy attacker by finding the flaw in his attack.

In addition, when a player organizes his pieces for attack they are usually ill-prepared for defense: Attacks often fail. Counterattacks rarely do.

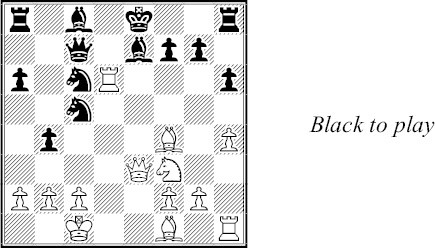

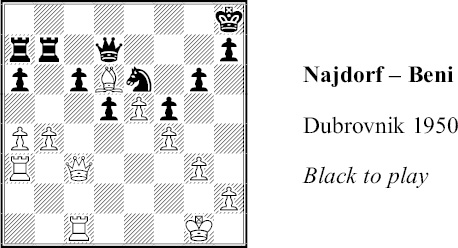

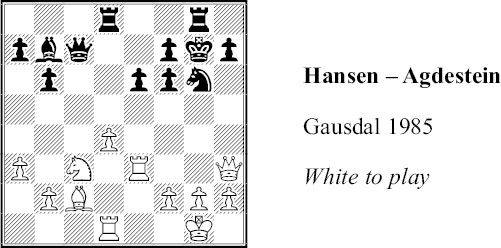

Black’s king has to deal with dangers such as ♕h5/♖h3 followed by ♕h6+! and mate. White played the natural – but lazy – 1 ♕h5?. (Better was 1 ♖g3 first, with unclear chances.)

Black replied 1 ... ♗xg2!. This is justified by 2 ♔xg2? ♘f4+ and ... ♘xh5. It is based on something that defense-hating amateurs need to constantly remember: The defender has just as much right to use tactics as the attacker.

Shaken by 1 ... ♗xg2!, White replied with 2 f3, to trap the bishop and create a king escape square at f2. Black could have tried to extricate the bishop, say with 2 ... ♕f4.

But he took command of the kingside instead with 2 ... ♘f4! and then 3 ♕xh7+ ♔f8. Tactics have turned him into the attacker. He threatens to win with discovered checks on the g-file. He could punish 4 ♕h6+ ♔e7 5 ♔f2 with 5 ... ♖h8! and the queen is trapped.

The game ended quickly: 4 ♔f2 ♘h3+ 5 ♔e1 ♕f4 6 ♖ad3 ♗f1! 7 ♖e4 ♗xd3! White resigned (or 7 ♔xf1 ♖g1+ 8 ♔e2 ♕xh2 mate).

And let’s dispose of one final myth:

You only learn defense through experience.

You hear this all the time: “You can’t teach yourself how to defend. It comes from playing hundreds of games.” Or, rather, “It comes from losing hundreds of games.”

Now, it’s true that some of the attributes of good defenders, such as patience and coolness under fire, are hallmarks of veteran players. They have learned to take their time and how to deal with crises.

But some of history’s greatest defenders – Anatoly Karpov and Sammy Reshevsky, for example – developed those skills when they were very young. And there was also a certain 11-year-old who showed us how to defend:

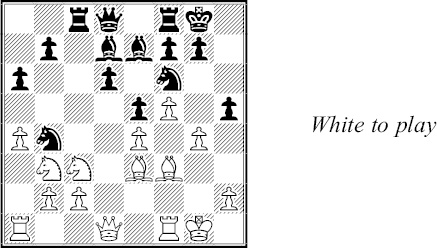

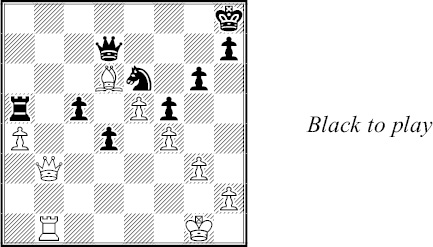

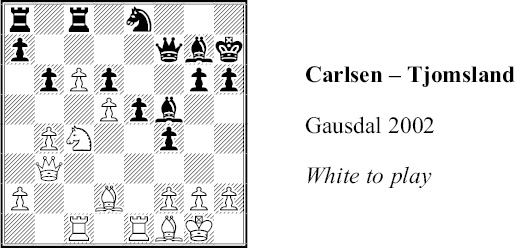

With considerable ingenuity White had created a powerful passed pawn at c6. In an endgame that would likely be a decisive factor. But the d5-pawn that protects the c6-pawn is threatened by ... ♕xd5. And 1 ♘a3 would be met by 1 ... ♘f6 2 ♗c4 ♗e4.

Magnus Carlsen played 1 ♕f3. He knew that 1 ... g5 looked dangerous because 2 ... g4 would knock his queen away and either win the d-pawn or continue his kingside initiative.

His reply, 2 g4!, was strong because White would get control of the light squares following 2 ... ♗g6 3 ♗d3! or 2 ... fxg3 3 hxg3 and ♘e3.

For better or worse, 2 ... e4 was the natural reply ...

... and so was 3 ♖xe4! and 3 ... ♗xe4 4 ♕xe4+. At fairly cheap expense (a pawn for the Exchange) White secured his kingside and his pawn chain. Play continued 4 ... ♔g8 5 ♗d3.

Black was not done. He was able to stabilize the queenside, 5 ... b5 6 ♘a3 a6 7 ♕f3 ♘c7, and then put his rooks to work on the open file, 8 ♗e4 ♖e8 9 ♕d3 ♖e5 10 ♗c3 ♖e7.

White is one piece – a well-placed knight – away from proving he has a big edge. He would like to play 11 ♘c2 and then ♘d4-f5. But 11 ... ♗xc3 12 ♕xc3 ♖xe4 costs a piece. So he settled for 11 ♘b1, with ideas such as ♘d2-b3-d4 and f2-f3.

Black appreciated how desperate his situation was and went for the highrisk 11 ... f3. The pawn will be lost there but he wanted to stop the stabilizing f2-f3 and create the option of ... ♕f4 and an undermining ... h5. He gets some e-file play after, say, 12 ♕xf3 ♖ae8.

White responded 12 ♖e1! ♗xc3 13 ♘xc3 ♕f4 14 h3. This was the time for 14 ... h5 (15 gxh5 g4 and 16 ♔h1 or 16 ♕e3 is still difficult).

But Black’s 14 ... ♖f8? was too slow and White took command with 15 ♖e3! h5 16 ♖xf3 ♕c1+ 17 ♔g2. He would have been winning in the long run after 17 ... hxg4 18 hxg4.

But Carlsen used tactics to win faster with 17 ... hxg4 18 ♗h7+! ♖xh7 19 ♖xf8+ ♔xf8 20 ♕xh7 ♕xc3 21 ♕f5+. He had foreseen that he can win the knight and the d-pawn with checks: 21 ... ♔e7 22 ♕d7+ ♔f8 23 ♕xd6+ ♔e8 24 ♕d7+ ♔f8 25 ♕f5+!.

Now 25 ... ♔e8 26 ♕c8+! and 27 ♕xc7+/hxg4 is an easy win. Black chose 25 ... ♔e7.

Here 26 ♕xg5+ is tempting but there’s a lot of game left after 26 ... ♔f7. White found the more accurate 26 d6+! and Black resigned (26 ... ♔xd6 27 ♕d7+ forces 27 ... ♔e5, when 28 ♕g7+! skewers the king and queen). Yes, that’s an awful lot of calculating. But, as noted earlier, White could also have won with simple moves such as 18 hxg4.

You don’t have to be a great calculator to be a good defender. You need the right tools, beginning with the proper spirit and attitudes. Let’s see what those are.