“I BELONG TO DE MISTIS”

In July 1847, Sarah Ann Davis married a widower named John C. Bethea in Marion County, South Carolina. She was twenty-nine, and he was twenty years her senior. According to the legal doctrine of coverture, the change in Sarah Davis’s marital status made her a “feme covert.” As such, her “very being” and “legal existence” were no longer hers; they had been subsumed into her husband’s. The English jurist William Blackstone, who penned one of the most oft-cited explications of the legal doctrine of coverture, reasoned that the newly wed woman no longer needed an independent identity because, likening the husband to a bird, her groom offered her “cover” under his wing.1

From Sarah Davis’s perspective, this wrenching of her rights and the legal denial of her independent existence probably appeared altogether different. Coverture would be particularly onerous for a woman like Davis because she received a number of slaves from her father, Francis Davis, upon his death and inherited more from her aunt, Elizabeth McWhite, when McWhite passed away several years later.2 According to the doctrine of coverture, the enslaved people that her father and aunt bequeathed to Sarah became her husband’s once they married. He had the right to sell them, benefit from their labor, collect the revenue they produced, and dispose of them as he deemed fit. Since Sarah was a feme covert, and she no longer owned or controlled her property, she had no right to sell her slaves, either. The legal doctrine forbade her from engaging in commercial endeavors in her own name and without her husband’s permission. If someone wronged her, she could not sue that person in court unless her husband joined in her petition and put forth the bill of complaint on her behalf. When Sarah made the choice to marry John, it was the last decision that she would freely make about her own life, at least until John died. Legally John “controlled her body and her property,” and “there were relatively few constraints on what he could do with either.”3

Assuming that Sarah and John adhered to the doctrine of coverture to the letter, this is how events were supposed to unfold on the Bethea plantation after they wed: Sarah would hand over control of her slaves to John, who would employ, discipline, and even sell them at his own discretion. But Hester Hunter, a formerly enslaved woman whom Sarah owned, did not remember things this way. According to Hunter, Sarah “had her niggers” and John “had his niggers,” and anyone who saw them could easily differentiate between the two groups. Hunter vividly recalled that if a person visited the Bethea plantation, he or she “could go through dere en spot de Sara Davis niggers from de Bethea niggers” as soon as “you see dem.”4

This was no accident. Sarah’s slaves were looked after “in de right way.” She cared for them when they were ill, made sure they ate well, and had their healthy meals prepared. In contrast to some slave owners in the South, Sarah made sure that the breakfast served to her slaves always contained meat. She also ensured that their clothes were well made and that they had a “nice clean place to sleep.” She never allowed her slaves “to lay down in rags.” She did not compel them to work on Sunday, and she made sure that they took care of personal chores, like washing and ironing, on Saturday, so they did not have to do them on the Sabbath. She did not permit the enslaved children she owned to work at all, or at least in their early years, and Hunter remembered playing with her dolls in the backyard “aw de time I wanna.” When asked about who handled, managed, and cared for the people Sarah owned, Hunter reinforced the fact that Sarah “see ’bout aw dis she self.”5

The distinctions between Sarah’s and John’s slaves extended to their accommodations. According to Hunter, the quarters where the couple’s slaves slept were divided into two long rows; one housed “de Davis niggers,” and the homes of the “Bethea niggers” formed the other. Hunter assessed the homes of Sarah’s slaves and compared them with those of her husband’s, which she considered inferior. Clearly, at least one member of this slave-owning couple wanted to demarcate the division of property even if it meant reconfiguring the architectural landscape of the plantation to do so.6

Sarah’s desire to protect her investment in slaves went farther still. Hunter recalled that her mistress never had the enslaved people she owned “cut up en slashed up no time”; she “wouldn’ allow no slashin round bout whe’ she was,” and she made sure that her husband refrained from punishing her slaves as well. One day when John set his mind to whipping one of Sarah’s slaves, she stopped him and said, “John C., you let my nigger alone.” He abided by her wishes. Sarah’s decision to refrain from inflicting certain kinds of punishment preserved the value of her property and ensured that her slaves were healthy enough to work the way she needed and wanted them to.7

The arrangements that Sarah and John made that Hunter described were neither rare nor exceptional.8 The enslaved people that women owned routinely described similar circumstances in their interviews with FWP writers. Yet these and other dimensions of life within slaveholding households, including agreements like Sarah and John’s, have remained obscure because they occurred away from the public gaze. Even so, during slavery and long after it ended, the enslaved people that white women owned talked about their mistresses and how these women challenged their male kinfolks’ alleged power to control their property, human and otherwise. Formerly enslaved people like Hester Hunter also make clear that while their female owners’ humane treatment toward their slaves might appear to be motivated by benevolence or to spare them abuse, their grounds for contesting their husbands’ authority were in fact predicated upon their position as slave owners who possessed the right and power to control their own property as they saw fit. Formerly enslaved people also described how their female owners’ propertied status often formed the basis of marital conflicts and how these women’s economic ties to slavery, their legal titles to enslaved people, and the juridical protection of their property rights configured the internal order of their households and influenced their interactions with individuals beyond them.

Many of these women had inherited enslaved people, some when they themselves were infants and girls. Slave-owning kin gave brides-to-be enslaved people as wedding gifts, which served to augment their economic investments in slavery at a time when historians contend that married women endured “civil death” and had no other choice but to resign themselves to their fate.9 Countless studies have chronicled the lives of married women in the slaveholding South who were indeed constrained by the legal doctrine of coverture. But some wives found ways to circumvent the constraints that coverture imposed. For them, relinquishing the control they had cultivated since girlhood was not something they were willing to do without a fight. Marriage did not constitute civil death for these women. It marked another important life transition that allowed them to put the strategies of slave management and discipline that they learned as girls into practice and to increase their control over enslaved people.

The recollections of formerly enslaved people include descriptions of how slave-owning women sought to protect their human property within and near their households, and lay bare the confrontations and conflicts that ensued as a consequence. Yet people within and far beyond southern households routinely acknowledged that women in slaveholding households could in fact be slave owners in their own right who had the authority to control and dispose of the enslaved people they owned as they deemed appropriate. The actions of community members and representatives of the state also reveal that individuals outside the household acknowledged the legal title that even married women had to their slaves.

Slave catchers captured runaway slaves for female owners and took them to local jailors, who subsequently called upon these women, not their husbands, to retrieve their property. Newspapers routinely included women’s advertisements concerning runaways, which identified them as lawful owners of those enslaved people and offered rewards for their capture and return. Women were counted among the slave owners enumerated in the Schedule of Slave Inhabitants, which contained data collected as part of the 1850 and 1860 U.S. federal censuses. When the state charged enslaved people with participating in insurrections or conspiracies, executed them, or sentenced them to sale outside state lines, court officials identified female owners in their judgments. Special committees often awarded these same women compensation for the loss of their human property, and if the amount proved disappointing, slave-owning women would petition the courts for more. Judges issued legal orders calling on women to have their slaves report to court in order to testify in cases against other enslaved people. Municipal officials compensated slave-owning women for the labor of enslaved people who assisted with public works. Other authorities issued receipts to women who remitted payment for taxes levied upon the slaves they owned.10 And when husbands and others jeopardized slave-owning women’s property rights, those women went to court, where judges routinely acknowledged their legal title to the enslaved people in question.

Given the standard view of coverture in the nineteenth century, much of this seems implausible. But truth be told, the doctrine of coverture was a legal fiction, and an imperfect one at that, and legislators and court officials seemed to know it. As the historian Marylynn Salmon has aptly observed, it was premised upon the ideal marriage in which “men always acted wisely and fairly” and assumed the role of patriarch and household head with almost perfect precision. Legal cases made it clear that ideal marriages were rarely achieved, and propertied women often found themselves in dire circumstances as a consequence of their husbands’ poor judgment, misdeeds, and misfortunes.11

Jurists, the historian Hendrik Hartog asserts, came to know that “coverture alone offered little in the way of real protection for a wife.” This was especially true during and after the economic panics of 1819 and 1837, financial catastrophes that left many southern men insolvent.12 Under common law, when married men failed in their commercial and agricultural ventures, their creditors could seize their wives’ estates to satisfy their debts, and many women lost their inheritances and the property they had acquired through their own industry in this way. Courts began to require that married women be accorded private or “privy” examinations whenever they received requests to sell their property. These examinations served to confirm their decisions to sell and ensure that their choices were not a result of their husbands’ coercion. In many cases, however, husbands forced their wives to say that the decision to sell was their own and thereby defeated the intent of such examinations. Courts also mandated “women’s signatures on land deeds,” and they supported husbands and wives having separate estates.13 Additionally, in the mid-nineteenth century states began to pass married women’s property acts that granted women some control over their property. Although none of these protections was infallible, they signaled that legislators were attuned to the problems inherent in endowing husbands with unlimited power over their wives’ property.14

But long before the widespread legislative acknowledgment of the short-comings of coverture and the passage of these protective laws, slave-owning kin took steps to reduce the risks associated with granting husbands absolute power over the property of soon-to-be or already married women. Such protections proved to be especially important in the first decades of the nineteenth century, when many young couples were trekking to the West and Deep South. Male suitors from long-standing communities could be vetted, and their boasts of wealth and excellent pedigree verified. But when they moved to the West, they could reinvent themselves and misrepresent their financial circumstances to the women they courted. Emily Camster Green’s owners, for example, gave her to their daughter Janie when she married. Before Janie and her prospective husband said their vows, he had convinced her that he “had a big plantation an lots o’ money” in Mississippi. Later, Janie was devastated to discover that the plantation he claimed to own actually belonged to one Joe Moore and that Moore employed her husband as an overseer. She had been courted by many suitors, but, sadly, Green remarked, Janie “jes took de wrong one.”15

Men like Janie’s husband lied in order to attract propertied and well-to-do women in hopes of securing their estates or, as one woman claimed, “to make property in a way more easy than to work for it.”16 Slave-owning women frequently alerted each other to the risks that dubious suitors presented. They also wrote about the woes of property-owning women they knew who seemed blinded by love and oblivious to the dangers unscrupulous men posed to their economic security.17 Sharing such knowledge could reduce some of the financial risks associated with choosing the wrong mate, but not all of them. It was essential for families to protect their female kin’s financial well-being in whatever ways they could. Parents frequently gave their daughters less “real” property—land—than they gave sons. They also imposed limits upon the amount of time their female kin could hold property, usually granting them “life estates” that accorded them ownership for their lifetimes, after which the estates passed on to their children.

Historians tend to interpret parental decisions to limit their daughters’ control over property in this way as an indicator of filial gender bias, particularly among fathers, and paternal favoritism shown to sons. However, slave-owning fathers as well as mothers left their daughters and sons life estates. On November 15, 1836, for example, Nancy Boulware drew up her will, in which she granted each of her two sons and her three daughters life estates comprised primarily of the slaves she owned. When Nancy’s son Thomas drew up his will, he elected to bequeath enslaved people to his sons and daughters for their lifetimes as well, in emulation of his mother’s vision of property distribution.18

Some slave owners consulted with family members about their preferences before writing their wills, and their legatees responded in ways that reflected their own interests. If the bequests involved property, legatees often made requests based on their ability to manage the property in question, sometimes suggesting that the land or slaves they were set to inherit be sold so that they could receive the proceeds from such sales. Sarah E. Devereux’s mother-in-law consulted with her about what kind of bequest she preferred to receive on behalf of her young daughters. Devereux thought “it would be far better to have their money than land and Negroes,” because if she received land and enslaved people she would have to depend upon her brother-in-law for assistance. She and her daughters lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where slavery had long been abolished, and state law prohibited her from holding individuals in bondage. She had no intention of moving south and preferred to manage her daughters’ legacies herself.19

Sarah Devereux knew firsthand how troublesome such arrangements could be. Although she and her daughters lived in Connecticut, she still maintained a plantation and cultivated cotton in North Carolina. She had to rely on an overseer, local factors (brokers), and her deceased husband’s family for help in managing the estate, selling the cotton, and preparing it for shipment. They would send Devereux updates, but she also kept herself informed about the cotton market and drew upon the knowledge she gained when she wrote to her brother-in-law regarding her concerns about the current price of cotton in the overseas market. So when considering her daughters’ inheritances, she hoped to avoid similar cross-regional endeavors if she could.

These scenarios suggest that when elders devised their wills, many considerations influenced their bequests, such as whether slavery existed in the states where their heirs resided or how best to frame bequests that involved minor children. Testators, then, could decide to bequeath their property in ways that had little or nothing to do with a bias against heiresses or ideas about female ineptitude.

Among the most important steps a woman and her family could take to circumvent the constraints of coverture were devising an antenuptial or marriage contract, which resembled a modern-day prenuptial agreement, or drawing up deeds of gift, deeds of trust, and wills that granted her control over all property she already owned or would acquire during her marriage. Although the historian Michael B. Dougan claims that antenuptial agreements were “legally valid but not practically useful [and] of little use to young couples just starting out,” and another historian, Woody Holton, argues that trust estates did not grant women separate property at all, both of these proved to be true only under certain conditions.20 Looking closely at the language of such agreements we can see that women and their families constructed them in ways that forbade their present and future husbands from having any control over their property. A husband could not dispose of it, and the property was not liable to seizure for his debts.21 Some trust deeds went even farther, requiring trustees to consult with the female beneficiary before they made any changes to the estate and to obtain her consent before altering the trust in any way. Others added language that granted the woman all the income the property in the trust produced, as well as the power to control the property, dispose of it, or mortgage it, or to buy more property, as she saw fit, even though she had a trustee.22

The people drawing up such documents were as specific as possible when itemizing the property and assets involved, because they understood that omissions could lead to the seizure of any property not explicitly included. Such documents might also indicate that a married woman was entitled to the wages her slaves earned when they were hired out to others and that she possessed the crops that her slaves cultivated. Furthermore, when a woman owned enslaved females, she and her family made sure to secure her legal title to the “future issue” or “increase” of those slaves as well. Such a contingency secured property that could amount to thousands of dollars in the future. As a formerly enslaved woman named Mary Jane Jones observed, the gift of an enslaved female served “as a kind of nest egg” that parents gave to their children. Jones’s own mother was a gift from father to son, and the intent of this gift was to enable Jones’s mother to “breed slaves for him.” After Jones’s master took her mother home “he bought a slave husband fur her,” and “children came to both families thick and fast.” As Walter Johnson contends, “Slaveholders articulated their own family lines—their worldly legacies—through the reproduction of their slaves,” and slave-owning women also benefited from this kind of calculus. The woman who owned F. H. Brown’s family, for example, “got her start off of the slaves her parents gave her.” She owned Brown’s grandmother, who bore twenty-six children during her lifetime. Before freedom came, Brown’s mistress owned seventy-five slaves in her own right.23

Close examination of the stipulations and clauses included in these documents reveals how practically useful these contracts could be for slave-owning women and the preservation of their property rights after marriage. Sarah Welsh’s marriage agreement with her husband, Dennis, not only protected her property, it established her legal right to own, control, sell, and bequeath it in any way that she considered appropriate. At the time of her marriage to Dennis Welsh, she was “sole and unmarried” and owned “tenements, lots, houses, parcels, tracts of land in Mobile, Alabama,” twenty-seven slaves who were considered her “personal property,” and ten stock shares in the Planter’s and Merchants’ Bank of Mobile, as well as other personal property. She devised a marriage agreement that reserved it all for her “sole, entire and exclusive use, benefit and enjoyment.” The agreement empowered her to “have, take, use, enjoy, receive all the rents, issues, and profits of all said above described real estate, all the hire and personal services and labours of said Negro slaves and of said horses, [and] all the dividends and interest on said ten shares of stock in the Planters and Merchants Bank of Mobile.” It also specified that she should “in no [manner] be interrupted . . . in her full sole and exclusive use and enjoyment, management and control, and disposition of the same.” She appointed Richard Redwood as her trustee and granted him the authority to sell, rent, hire, or otherwise dispose of her property, but only as she “may think proper . . . and may direct.” Additionally, she specified that he could do so only with her “written request fully given in the presence of six reputable persons and in the absence of the said Dennis.” She reserved her right to draw up a will and to “give, devide [sic] and bequeath to any person or persons all of any part of [her property] . . . as she . . . may think proper.” To ensure that her husband did not “defeat, obstruct or impede . . . the true intent and meaning” of her will, she required that it be “duly signed, sealed and executed, published and declared in [his] absence . . . and in the presence of four reputable persons, one of whom shall be a clergyman.” Dennis agreed to all the terms and signed the contract.24

The months and days preceding the wedding ceremony were critical for a slave-owning woman because she had to decide whether she trusted her prospective husband’s professions of love, sobriety, financial security, and strong ethics enough to enter into marriage without a contract like Sarah Welsh’s, or whether to err on the side of caution and insist on a settlement that protected her interests. Such decisions were not easy in part because prospective husbands could be reluctant or outright opposed to such provisions. A woman who confronted a recalcitrant fiancé could issue an ultimatum making the marriage conditional upon his acceptance of the marital settlement. A marriage settlement was especially important when a woman did not know the details of her future husband’s past. Mary Williams, for example, had inherited a considerable estate from her deceased parents that she possessed in her own right. When William Williams proposed marriage, he was a widower with a large family and a sizable amount of debt. Knowing this, and not wanting to risk her own financial stability, Mary had “utterly refused” to accept William’s proposal unless he agreed to “a marriage contract or settlement” that would reserve to her “for her own benefit her property of every description and money and choses in action [personal property] of every description . . . in short all that was hers in her own right.” She also insisted that their contract emancipate her two slaves upon her death. Her goal was not merely to ensure that she had complete control over her property while she was living but also to ensure that it would not be subsumed into William’s estate if he were to die before her, as the law required.25

Slave-owning widows who considered remarrying were especially keen to approach these decisions cautiously and sought to protect their property from possible misjudgments.26 They often made their second, and third, marriages contingent upon antenuptial agreements. Eliza Strickland was a widow who owned land, slaves, and “other personal property ample for her respectable and comfortable support and maintenance.” She was engaged to Barnabas Strickland and described him, when she later hauled him into court, as “a stranger recently from the State of Georgia [who] was introduced to her as a churchman of the Baptist denomination . . . a man of specious manners and respectable appearance and a minister of the gospel.” Yet because she was “ignorant of [his financial] circumstances,” she “consented to marry him only on condition that, by an ante-nuptial contract, her property should settle upon her absolutely as her sole and separate estate.” This, she contended, was “an act of precaution.” Her apprehensions proved justified when she learned that Barnabas was heavily indebted to people in his home state.27 Women who failed to protect their property during their first marriage generally recognized their mistake and took care not to make it again. Others hoped that their second husbands would be more adept at managing their property than their first had been. But if their second husband dashed those hopes and squandered their property, some women set out to prevent more waste by petitioning courts for permission to establish postnuptial agreements, which granted them the right to create separate estates after their marriages began. The married women who sought these postnuptial agreements did not wish to be separated or divorced from their husbands; they merely sought to protect their property from their husbands’ financial blunders.28

Once kin and couples had drawn up a marriage settlement, states like North Carolina required them to authenticate or prove it in the same manner they did other deeds. Couples needed to put the settlement in writing, sign it in the presence of “one credible subscribing witness,” and register the agreement “in the office of the public register of the county where the donee reside[d].” They needed to complete this process within “one year after the execution” of the settlement.29 Clerks in local county courts then recorded the settlement in a deed book.

As women left their home states in the Southeast and moved farther west with their husbands, they would file authenticated copies of these documents in the courts of their new residences.30 Even in cases when they were not mandated to do so, women would often record the contracts or petition for recognition just to ensure that their local courts would recognize and protect their legal title to the enslaved people they brought with them as they migrated. In November 1841, while still a resident of Mississippi, Susan Hunter purchased eighteen enslaved people on three separate occasions. She later moved to Kentucky, and shortly after her arrival, she went to court to have her legal title to these slaves recognized. She had been advised that Kentucky law granted “a married woman . . . the right to purchase slaves or other property and hold the same to her own ‘separate use,’” and she asked the court to recognize her right to hold these slaves for “her sole and separate use” in the state.31 The court acknowledged Hunter’s ownership of the slaves she named in her petition.

When Spanish Florida became an American territory, slave-owning women living there acquired a new opportunity to reassert their property rights. Although their property rights had been accorded under the Spanish regime, they took their cases to American courts to establish them in the common (and equity) law systems that prevailed in the United States. In 1831, Victoria Le Sassier entered the Escambia County Courthouse in Pensacola to inform the court that she had no intention of relinquishing her property rights. In her petition to the Superior Court of West Florida, she stated that “by the laws of the Spanish Monarchy subsisting and in force in the Province of West Florida prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty two,” she was “entitled to her separate property independent of the control and disposition” of her husband and this “right had in no wise been changed by the transfer of the Province to the United States.” She also told the court that the “said property was secured to her by the treaty of cession and by an act of the Legislative Council in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty four.” The court recognized and upheld her right to hold separate property, which included twenty enslaved men, women, and children.32

In Louisiana, where civil law prevailed, the state’s system of property law also allowed married women to hold certain kinds of property in their own names, to control it, and to dispose of it without special provisions.33 Even so, women in the state often insisted on signing antenuptial contracts with their future husbands, and they also sometimes sued their husbands for a “separation of property” after they married. A separation of property was a provision that allowed a married woman to legally separate her property from that of her husband, but she could do so only under specific circumstances. Louisiana courts required married women who sought a separation of property to prove that their husbands’ pecuniary affairs, fiscal mismanagement, or economic circumstances jeopardized their own property and economic well-being. One such form of evidence was a husband’s indebtedness to his wife or his misuse of her “paraphernal” (separate) or her “dotal” (dower) property, which she would continue to own after marriage, but would have placed under his management.

When courts granted such requests, these women were legally empowered to control their “movable” property and administer it as they saw fit. Although the law did not immediately grant them the right to do this with their “immovable” property, it contained a contingency clause that allowed them to do so with their husbands’ consent or with the court’s permission if their husbands refused. It might seem logical to assume that enslaved people would fit the definition of movable property, but in fact they were considered “attached” to the land, and thereby legally immovable.34 Women who lived in Louisiana thus had to complete extra steps to secure and maintain control over the slaves they owned, and many did so.

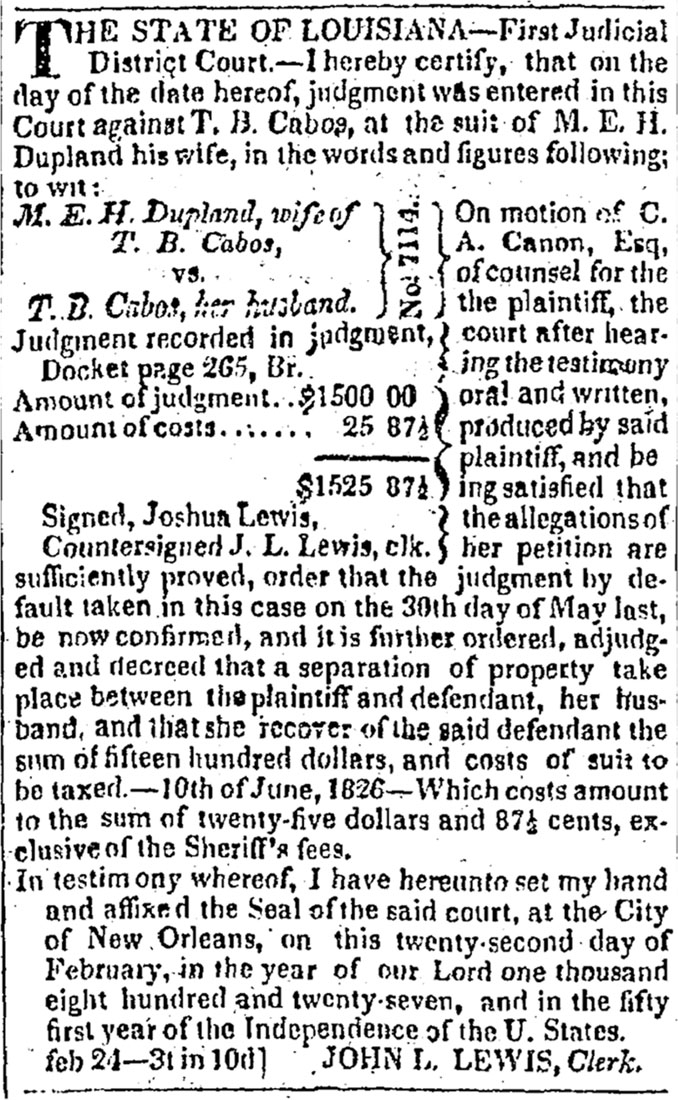

Once a married Louisiana woman had legally separated her property from her husband’s, the court required her to publish a notice of the separation, in English and French, at least three times, in two local newspapers. These notices included the date of the judgment, the names of the plaintiff (wife) and defendant (husband), the case or docket number, a statement about the nature of the suit, the amount of money the wife sought to recover from her husband (to repay his debt to her), the nature of the judgment, the judge’s name, and the verification by the Deputy Clerk.35

Separation of property notices published in local newspapers were critical because they served to alert the couple’s community and their creditors about the change in the wife’s legal status and her newly expanded control over her property. It was imperative for a married woman to make sure the notice was published because doing so reduced the likelihood that her husband’s creditors would challenge the legitimacy of her separate property status and seize her assets to pay her husband’s debts, something that happened frequently. When creditors seized what they thought was Walter Turnbull’s property to satisfy an outstanding debt, his wife, Matilda, filed an injunction preventing them from taking further action because she—rightfully—claimed the property belonged to her. Walter Turnbull’s creditors rejected her assertion and stated that her separation of property was null and void because she had not published a notice of the court’s judgment in local newspapers as the law required. The lower court agreed with the creditors, and Matilda appealed. Her counsel presented all the evidence reviewed by the Sixth District Court to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which ruled that while she should have published the notice in a timely manner, the “judgment of separation, unattended by publication [was] not ipso facto void,” and the court thereby “annulled, avoided and reversed” the lower court’s ruling. Matilda’s separation of property was upheld and her injunction reinstated. Some other women were not so lucky.36

Separation of property notice documenting the outcome of M. E. H. Dupland v. T. B. Cabos, Louisiana Advertiser, February 27, 1827 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

Separation of property notices publicized husbands’ indebtedness to their dependents for friends and foes to see. Long-time citizens of Louisiana would probably know that a separation of property case had been filed because the wife believed that her husband’s finances and commercial behavior threatened her economic stability. The notices signified a husband’s irresponsibility and assaulted the sanctity of patriarchal households by unveiling typically private marital and financial affairs. Yet southern women filed them regardless. Rulings on separations of property and the subsequent publication of the notices undoubtedly delivered a severe blow to many a husband’s ego. Charles N. Rowley was so appalled by the court’s decision to grant his wife, Jane, a separation of property that he challenged the judge to a duel and killed him.37

Throughout the antebellum period, married women consistently asserted their rights to own and control human property without their husbands’ interference, and they exercised those rights as well. Enslaved people witnessed altercations and overheard arguments between married slave-owning couples, and they and their fellow bondsmen were often the subjects of those disputes. Married women reinforced their property claims in conversations with or in the presence of their slaves, and formerly enslaved people later paraphrased these conversations, such as the one Morris Sheppard remembered. He told his interviewer, “Old mistress . . . inherit about half a dozen slaves, and say dey was her own and old Master can’t sell one unless she give him leave to do it.”38 These spousal confrontations over property do not conform to historians’ usual claims about the legal doctrine of coverture. Nor do they seem to reflect the gendered, hierarchical organization of nineteenth-century households that most historians describe. To justify their arguments, some historians argue that enslaved people were not in a position to know about their masters’ and mistresses’ “property rights” and “the law.”

In truth, enslaved men, women, and children knew far more about white women’s property and the law than they often disclosed, especially when they were the “property.” The case of a wrongfully enslaved woman named Winney offers an example. On February 19, 1844, in Jefferson County, Kentucky, Winney sued the heirs of her deceased owner, Elizabeth Stout Whitehead. During her years of service to Whitehead, Winney had learned that before her marriage to William Whitehead, her mistress had signed a marital contract that “expressly agreed that each party should retain to him and herself the entire and exclusive right to the property owned by each before the marriage with the right to dispose of the same in such a way, as they should respectively choose to do.” Winney had also learned that the contract included a provision that stipulated she was to receive her freedom upon Elizabeth’s death. She knew that Elizabeth and her husband had not filed the contract with the court but had given it to the Reverend William Stout for safekeeping. Winney petitioned the court for her freedom and challenged her deceased owner’s heirs, who were claiming her as a slave. Elizabeth’s marriage contract had been lost or mislaid, but Winney submitted a letter from the minister that corroborated her account of the facts. In his remarkable answer to Winney’s petition, William Whitehead’s son John, who was also the administrator of his deceased father’s estate, said that he had witnessed the marital contract described in Winney’s petition “at the request of his step mother Elizabeth Whitehead.” He also stated that he knew from his stepmother’s “repeated declarations before her death, that she had an earnest desire” to emancipate Winney. Furthermore, he had “often heard that there was a marriage contract between his father and Mrs. Elizabeth Stout before their marriage.” Based on his recollections, and after receiving Reverend Stout’s letter confirming the existence of the contract, he told the court that he “cannot and he will not gainsay [Winney’s] right to her freedom.” He asked that “justice be done.” Winney won her freedom.39

Although Winney achieved a positive outcome to her petition, John’s admissions in his answer to her legal suit highlight how the heirs of women like Elizabeth Whitehead could be privy to these women’s wishes with regard to the slaves they owned yet refuse to respect them. Well before John Whitehead became his father’s administrator, he knew that the marital contract between William and Elizabeth existed, and he possessed firsthand knowledge of his stepmother’s desire to free Winney after her death. And yet when he drafted the inventory of his father’s estate, he listed Winney as a slave and made no subsequent arrangements to free her. John Whitehead’s initial decision to ignore his stepmother’s wishes illustrates a common obstacle that enslaved people such as Winney had to overcome. It also compels us to reconsider his seemingly benevolent response to Winney’s legal complaint and approach similar declarations with caution.

Winney was one of many enslaved individuals who petitioned the courts for freedom based on their understanding of the terms set forth in their deceased owners’ wills or marital agreements.40 But even more enslaved and formerly enslaved people who never entered southern courts were aware that their female owners had protected their ownership rights with similar legal instruments. The reflections and remembrances of these individuals reveal that enslaved people knew a great deal about women’s property rights and the law.

As the fugitive slave and later abolitionist James W. C. Pennington noted, every change in the financial, social, and personal affairs of a slave owner and his or her children could have traumatic consequences for enslaved people. An enslaved person’s familial and community stability was inextricably linked to his or her owners’ solvency and decisions about the disposal of their wealth. Out of necessity, African Americans came to understand critical features of southern law. When slave owners became insolvent and creditors sued them to recover debts that remained outstanding or when slave owners died and their estates were distributed according to their wills or in the absence of them, enslaved people were among the most affected. If they hoped to purchase their freedom or the liberty of loved ones, they needed to know how a basic contract worked. As commodities that could be bequeathed, seized, exchanged, hired, bought, and sold, they became intimately acquainted with the values their owners affixed to them. They also came to understand slave owners’ inheritance practices, debts, loans, sublets, renting practices, installments and time payments, and mortgages. Enslaved people were knowledgeable about property and legal claims to it, both as chattel and as property owners in their own right.41 Furthermore, they listened to their female owners’ conversations about how they wanted the slaves they owned to be treated and used, and they understood that these women’s assertions were grounded in what they considered to be their personal legal rights.

Abundant evidence from publicly available documents such as court records and newspapers supports enslaved people’s claims that community members and representatives of the state recognized women’s legal titles to human property. When an enslaved person ran away from his or her female owner, for example, runaway notices alerted the community to the owner’s title to the fugitive. A woman would identify herself as the enslaved fugitive’s legal owner and place ads in newspapers offering a reward for the slave’s capture and return. Elizabeth Humphreyville’s 1846 advertisement is an example. She operated a boardinghouse in Mobile, Alabama, and through her earnings was able to purchase two enslaved females named Polly and Ann. When Ann was “pretty far advanced in pregnancy,” she ran away, and someone told Humphreyville that Ann had probably fled to a plantation located four miles from Pensacola, Florida. Based on this tip, Humphreyville placed an advertisement in the Pensacola Gazette offering a fifty-dollar reward to anyone who seized Ann and confined her in the guardhouse in Mobile until Humphreyville could claim her. Although Elizabeth Humphreyville deemed it likely that Ann had run away, she also considered it possible that her husband, Joseph, had stolen the woman. She accused him of pretending to be Ann’s owner, and she cautioned the public “not to trade for her as the titles to [Ann rested] in me alone.”42

Slave owners frequently identified slave-owning women as the owners of a runaway’s relatives in their advertisements because they presumed that fugitives might return to these women’s estates in hopes of reuniting with their loved ones.43

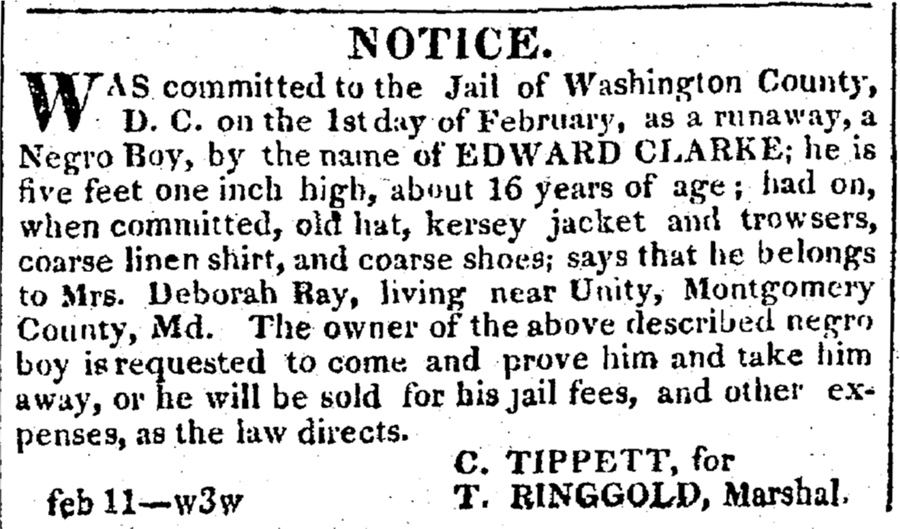

When individuals captured runaways, local jailors often held them until their owners could come fetch them. If they could not find the owners immediately, they posted “Committed to Jail” or “Brought to Jail” notices. One C. Tippett placed a notice in the Washington, D.C., Daily National Intelligencer stating that Edward Clarke had identified Mrs. Deborah Ray as the person who owned him. Clarke further specified the town and county where Ray lived. Tippett called upon Ray to come to the jail, establish legal title, and take Clarke back.44

Elizabeth Humphreyville’s (misspelled Humphyville) runaway advertisement for Ann, Pensacola Gazette, March 8, 1846 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

C. Tippett’s “Committed to Jail” notice in the Daily National Intelligencer, March 4, 1825 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

The total number of women who pursued their slaves by placing ads might be higher than can be judged from the newspapers because editors often printed advertisements that did not identify owners by name, telling subscribers to “Apply to the Printer.” Female owners might also be underrepresented in such advertisements because the names of their male agents might appear as the contact persons. But these documents nonetheless support formerly enslaved people’s recollections of having female owners, illustrating the ways slave-owning women made their propertied status known to others and showing communal recognition of that status.

Municipal officials also publicly recognized women’s legal claims to enslaved people. In fact, sometimes two women might claim to own the same enslaved person, and when that happened, these officials faced the same kind of legal hassle that often arose in their attempts to determine rightful ownership when male disputants presented them with competing claims. In 1841, James C. Norris was master of the Charleston, South Carolina, workhouse, an establishment where slave owners often sent their slaves to be confined and punished. (Local courts also sent enslaved people to the workhouse if they were convicted of committing crimes.) On February 28, on what was shaping up to be an ordinary Sunday for Norris, he agreed to confine an enslaved woman named Martha. Henry W. Schroder had lodged Martha in the workhouse “as the property of his wife Mrs. A. E. [Ann] Schroder.” He left Norris with “positive instructions” not to give the woman “to any person whatsoever other than him” or “his wife . . . A. E. Schroder.” A few days later, “Miss Ann Bell of Charleston caused a demand to be made, and did afterwards make a demand” that Norris give Martha to her because she claimed the enslaved woman “as her own absolute property.” She, too, instructed Norris not to give Martha to anyone but her. When Ann Bell returned to the workhouse to retrieve Martha, Norris refused to give the enslaved female to her, and Bell sued him in the Court of Common Pleas for Charleston, entering a writ of trover (the wrongful taking of property) against him for “converting and disposing of [her] goods and chattels,” and asking the court to award her one thousand dollars.45

Norris went to Schroder and told him about Bell’s claim and her suit. Schroder insisted that Norris adhere to the instructions he had given and threatened to sue Norris if he disobeyed or refused to give Martha to him or his wife when they asked for her. He told Norris that Martha rightfully belonged to his wife via a bill of sale issued to her father, Charles C. Chitty. At the time of Martha’s purchase, Ann Schroder was still a minor, and because of this, Charles Chitty had created a trust, which included Martha, and secured the property to his daughter for her “sole use . . . until she should arrive at the age of twenty-one years.” At that time Martha would belong to her “absolutely” and be “discharged from the trust.”46

All of this presented Norris with a costly dilemma. As the master of the workhouse, he was legally and financially responsible for the loss of any enslaved people confined within the establishment, and if he handed Martha over to either woman, while both claimed her as their “bonafide property,” the other could sue him for Martha’s value. In fact, the court record reveals that Ann Bell had already sued him, so his fears were well founded. To spare himself further trouble, he refused to give Martha to either woman and petitioned the court for assistance in determining which of them rightfully possessed legal title to the woman. He asked the court to make the Schroders and Bell interplead and “settle their rights to . . . Martha.” Once a decision had been handed down, he would be “ready and willing to deliver up [Martha] to whom the same shall appear of right to belong.” Although the petition does not disclose the outcome of the case, other documents show that H. W. Schroder was telling Norris the truth. On March 30, 1830, Catherine Roulain sold Martha and her six-year-old daughter Mary to Charles Chitty for $350, and the bill of sale indicates that Charles Chitty bought Martha and Mary for his daughter Ann Chitty (later Ann Schroder) in his capacity as her trustee. It also states that he bought them “for the sole use and behoof of his daughter until she shall arrive at the age of twenty-one,” at which time the trust would cease, and the two would belong “to her and her heirs forever.” In addition, the 1830 U.S. census shows that although Ann Bell owned two enslaved females, she did not own a six-year-old girl. Nor are there any documents indicating that Ann Schroder or her husband had sold Martha to Bell.47

Norris’s petition, and others like it, show that not only did public officials recognize women’s legal titles to enslaved people, these women’s husbands did, too. Norris’s petition also demonstrates that husbands might be the people who informed public officials about their wives’ slave ownership in the first place. Schroder might have been involved in many of the encounters described in Norris’s bill, but he consistently identified his wife, and not himself, as Martha’s rightful owner. Furthermore, Martha and Mary’s bill of sale revealed that not two women, but three claimed legal title to Martha at one time or another. Catherine Roulain was Martha’s original owner, and her name appears on the bill that recorded the sale to Charles Chitty. A witness, James Kennedy, attested to being present when she signed the document, and John Ward recorded it on March 31, 1830. The original transaction between Catherine Roulain and Charles Chitty, along with Norris’s case, offers powerful testimony of the broad recognition of women’s legal ownership of enslaved people.

Between and within the lines of formulaic legal jargon, the legal petitions brought by married women repeatedly informed jurists that coverture was not working. Not only were many husbands not “covering” their wives under their wings in the ways that Blackstone indicated, they were robbing their wives, squandering their assets, and violating their property rights. Worse still, many of these men had come to their marriages impoverished and proved to be irresponsible and incapable of exercising the rights which coverture afforded them. Finally, their ineptitude paved the way for their creditors to further breach what should have been inviolable boundaries that protected their wives’ separate property from seizure. Married women throughout the South called upon judges to step between them and their husbands, protect the property they claimed as their own, and prevent others from interfering with their enjoyment of the same. And when women’s legal affairs were in proper order, and their cases were strong, judges routinely heeded their calls.

White women’s petitions also document interfamilial conflicts over women’s human property wherein mothers sued their sons, aunts sued their nephews, and daughters sued mothers and fathers. Wives sued husbands over property that they considered rightfully their own. The historian Laura Edwards argues that when wives went to court to petition or sue over matters related to property, “ownership, in the technical sense of state law, was not really the issue.” In her estimation, wives were seeking the “restoration of the peace, not recognition of property rights.” When they appealed to the courts, they were effectively able to do so because their cases were not about “competing property rights, which would have pitted wives’ rights against those of their husbands.”48 Her analysis suggests that if women did indeed enter courts in an effort to secure legal recognition of their property rights or if their petitions pitted their rights against those of their husbands, they would have lost their suits. But white southern women were contesting other people’s claims to ownership of their slaves, and they were attempting to establish and legitimate their property rights “against those of their husbands.” Women appealed to courts when their husbands disposed of their property despite their directives not to do so. They also petitioned courts when their husbands’ creditors attempted to seize their slaves to pay their husbands’ debts. They routinely took action when their husbands overstepped the bounds of what they considered to be their rightful authority, thereby infringing upon their own property rights.

Feuding women and their family members were not the only people who found themselves hauled into court over married women’s slaves. A community member might accuse a woman of stealing slaves and leaving the state with them. Business agents brought claims against women for selling slaves to prevent creditors from seizing them. Others demanded payment for services rendered when women had separate estates from which they could comfortably repay their debts.49 Southern women answered these accusations, and their replies vividly demonstrate their willingness to appear in the most public realms of southern society to defend their property rights and challenge the power of anyone—including their husbands—to control the enslaved people they owned. Furthermore, the judges who adjudicated their cases often ruled in their favor.

Chancery courts, or “courts of equity,” were critical to a woman’s ability to control and manage her property and request legal intervention in maintaining it. Chancery courts as they came to exist in the United States developed in fourteenth-century England during the reign of Edward III. When British subjects could find no remedy for matters related to “trust, fraud, or accident” under the common law, they petitioned the king for relief and resolution of legal matters. He, in turn, created the Court of Chancery, appointing a member of his Council to serve as chancellor and assist him “in all cases in which natural justice, equity, and good conscience required his intervention.” British subjects would apply to the Chancery Court when they “wanted a remedy for [a] right or redress for a wrong that had been done” to them. The chancellor and his court “exercised an authority especially in favor of the weak, for repressing disorderly obstructions to the course of the law, . . . and affording a civil remedy in cases of violence or outrage,” which the common law could not address.50

In stark contrast to common law courts, jurists in nineteenth-century chancery courts treated married women as distinct persons, not as individuals joined in unity with their husbands.51 If a married woman entered into a contract with her husband, whether before or after the marriage took place, chancery courts would enforce it. If a wife placed her separate property in her husband’s hands as trustee or simply as manager, but the husband used or disposed of it in ways that she objected to, chancery courts would uphold her rights to that property and make her husband repay her for any property he had sold or squandered. Furthermore, if a husband incurred debts that he was unable to pay and his creditors seized his wife’s separate property, she could sue him and his creditors in chancery court to reclaim that property. Chancery courts also protected married women’s “pin-money,” small funds used to purchase consumer goods. Chancery courts recognized and protected any separate property that might be willed to married women or given to them as gifts, even if the property came from their husbands. And most important, chancery courts recognized a married woman’s right to possess and control a separate estate and dispose of it as the terms of the estate allowed.52 “With a separate estate,” Hendrik Hartog argues, “a wife gained a more separate self, a self not fully incorporated into the marriage, a self that an equity court could recognize as having choices and wishes, a self that could be revealed to have been coerced when a husband compelled certain outcomes.”53 Furthermore, when individuals gave women property through deeds of gift or trust that included protective clauses forbidding husbands from interfering with the property, chancery courts upheld and enforced these deeds.

Legal scholars and women’s historians have argued that when nineteenth-century southern jurists protected women’s interests they were acting as patriarchs. These men, they argue, stepped in to restore peace to households with faltering and fallible male household heads.54 Yet women’s bills of complaints make it clear that they had their own reasons for taking their cases to chancery courts and appealing to the judges who presided over them for remedy. They sought to protect, acquire, or reclaim property by any means necessary, and if that meant pandering to judges who considered themselves de facto patriarchs, they were willing to do so. No matter what southern jurists thought they were doing, court cases make it clear that the women who appeared, or were represented, before them used the courts for their own purposes. Women acquired and maintained legal ties to enslaved persons, and they were willing to bring spouses, kin, and others into chancery courts in order to protect their economic interests. These legal connections undergirded their economic relationships to the institution of slavery. Moreover, their legal title to enslaved people empowered white women within their households. They could determine who would be able to access their slaves and their slaves’ labor and who could discipline and manage them. On more than a few occasions, slave-owning women denied these privileges to spouses, kin, and community members and exercised complete control over the enslaved people they owned. Court records also documented the experiences of typical, not simply elite, slave-owning women, litigants who owned fewer than ten slaves. The majority, in fact, owned only one or two.

As Cornelia Hughes Dayton discovered in her examination of women’s experiences with courts in colonial New Haven, Connecticut, the records from southern chancery courts allow us to “hear women talking and being talked to” and to “see the extent to which they were recognized or ignored in the courtroom in a more tangible way than is possible in other public settings.”55 In their petitions to chancery courts, white women talked about their conflicts, problems, and concerns. But they also told judicial officials what their lives were like before the issues that brought them to court arose. They detailed routine household activities and interactions. And they talked about their slaves. They challenged those who claimed power over or ownership of the enslaved people they themselves owned. And when litigants claimed that they were lying about their legal titles to enslaved people, female petitioners presented court chancellors with evidence supporting their rights to the slaves in question. They documented chains of slave ownership that often led to and from slave markets. Although historians have asserted that wealthy women were the primary beneficiaries of separate estates, chancery court petitions show that most of the women who mentioned having slaves owned fewer than ten, making them average, rather than elite, slaveholders.

When women filed petitions in chancery courts, trustees or “next friends” frequently represented them and looked after their property interests. Female petitioners might have also sought legal assistance in drafting their complaints. The individuals who represented them and gave them advice were not always men; women also assumed these roles. And even when the people who assisted the petitioners were men, the experiences that shaped ordinary married slave-owning women’s lives were set down in chancery court records and became part of the public record.56

Formerly enslaved people routinely spoke of female slave owners who ensured that their legal titles to human property remained viable. And nineteenth-century legal records verify what these formerly enslaved people said about their mistresses. Clear parallels can be drawn between what enslaved people remembered about their female owners’ property claims and what these women said in their petitions. White women made the same kind of property claims within their households and communities as they did in the courtroom. Household-to-courtroom conflicts over enslaved property present critically important evidence that challenges historians’ prevailing understanding of how the law functioned and affected the lives of slave-owning women in the Old South.

Husbands were not always pleased when their wives possessed separate property or decided to manage it themselves. Betty Jones’s brother John, for example, purchased an enslaved woman named Nanny for her, and in the bill of sale he stipulated that Nanny and her offspring would belong to his sister and should be retained for her sole and separate use.57 Betty later married Isaac Jones, and although Isaac owned at least two hundred slaves of his own, he was unhappy about the fact that his wife owned property that he could not sell—and he did not hide his feelings. Nanny’s granddaughter Katie Rowe remembered that “Old Master [was] allus kind of techy ’bout old Mistress having niggers he can’t trade or sell.” On one occasion when he was entertaining family and guests, he brought them to the slave quarters. He called all the enslaved people together to stand before the visitors. He then made his wife’s slaves—Nanny, Katie Rowe, and Rowe’s mother—stand apart from the slaves he owned, and he proceeded to give his slaves a directive: “Dese niggers belong to my wife but you belong to me, and I’m de only one you is to call Master.” In Rowe’s recollection, “All de other white folks look kind of funny, and Old Mistress look ’shamed of old Master.”58

Some men resorted to deception and coercion, including domestic violence, to gain control of their wives’ property. They might refuse to give their wives copies of the contracts or even destroy the legal documents that granted their wives control over their slaves.59 Such tactics did not always stop these women from establishing boundaries related to their slaves and making sure that their husbands did not cross them. Sally Nightingale owned Alice Marshall and her mother, and Marshall claimed that her mistress’s husband, Jack, “ain’ had nothin’ to do wid me an’ my mother” because they “belong to mistiss by law an’ not har husband.”60

If a woman’s husband or her husband’s creditors still attempted to interfere with or seize her property despite their having separate estates, she might, as Mary Massie Leake did, seek legal remedy in a chancery court. Mary’s husband, Joseph S. Leake, had sold two of her slaves to John A. Dailey without her consent, though he had no legal right to do so. At the time of their marriage, Mary had appointed her mother, Susanna, as the trustee who would manage her separate property. Susanna ably assumed this role until her death. For reasons that remain unclear, Mary failed to appoint another trustee. Soon after her mother’s death, Joseph began to dispose of Mary’s property, some of it to Dailey, and she filed a bill of complaint against Dailey and named her husband as co-defendant. She asked the court to issue and deliver a subpoena to him, compelling him to “answer the allegations of said bill,” and to appoint a new trustee so she would no longer have to be “at the mercy of her said husband and his rapacious creditors.” She also asked the court to issue an injunction which would prohibit Dailey from disposing of her slaves or removing them from the state.61

Women like Mary Leake often delegated control and management of their separate property to trustees, and sometimes these were their husbands. Historians often interpret the decision to name a husband as trustee as an indication of a wife’s lack of interest in property ownership and control; sometimes they attribute the choice to a husband’s pressure or influence. But we should view these trusts and estates from another vantage point. First, a woman’s choice to elect a particular individual as her trustee was a crucial decision; it determined the level of control this individual, and others, would have over her property. Choosing the right person for this role was critical to preserving her legal title to slaves and making sure that others did not violate her rights, so she took care to find someone she could trust. A formerly enslaved man named Shade said it best when he observed that “any sort o’ man kin han’le his own money, but it takes er hones’ man to han’le other folks money,” and this is why so many women entrusted their slaves to family members.62 This was especially true since women had to navigate many more obstacles than men in order to secure control over property. And although historians frequently assume that women delegated their authority only to men, the evidence shows that they also called upon mothers, sisters, and aunts to serve as their trustees.63

If a married woman did not appoint a trustee of her own choosing, the courts typically appointed her husband to serve in this capacity unless circumstances made it impractical or unwise to do so. From our vantage point, a husband-trustee might appear to be managing and disposing of his wife’s property simply as husbands were entitled to do under coverture. But legally, this was not the case. When a husband acted as his wife’s trustee, the doctrine of “marital unity” under coverture did not apply in the same way in the eyes of the law. If a husband-trustee squandered or mismanaged his wife’s property in his capacity as such, she possessed the right to take her case to a chancery court and request that her husband be removed from the trusteeship and replaced. Take the case of Mary Ann Spears. When her father, John Goldsmith, died, he left all his children a portion of his estate, and when he specifically addressed the property he bequeathed to his daughters, he plainly indicated that he did not want their husbands to have any say in its management or disposal. Although her father’s intentions were clear, his use of plain language rather than legalese posed a problem when the creditors of Mary Ann’s husband, John, attempted to satisfy the debts he owed them by seizing her slaves. Mary Ann went to chancery court to ask for help in reclaiming them. She explained that her father “was a plain man with but a very limited use of Letters, and not at all acquainted with legal technicalities or the terms proper to use in the creation of separate estates of his daughters.” According to Mary Ann, her father had intended and “often expressed his determination . . . to vest the property given to his daughters to their sole and separate use or to the separate use of his daughters and their children, and to . . . free the same from all liability to the debts of their husbands and to exclude the marshal right of [their] husband[s].”64

When Mary Ann Spears’s father died and some of his property was conveyed to her, she appointed her husband as her trustee. Although he managed the property for her, she assured the court that he “again and again recognized said property as the separate estate of your oratrix.” Mary Ann told the court about an incident that she believed demonstrated her husband’s acceptance of this. While acting as her trustee, John decided to sell an enslaved boy she owned. She refused to “unite in a conveyance” or “ratify [the] sale or bargain” unless the proceeds arising from the sale could be “invested in another slave.” After she and John came to an understanding about this contingency, and he agreed to her demand, she ratified the sale, and the proceeds “were in part reinvested in the purchase of a Negro woman Selah.”65

As a consequence of his being “improvident and wasteful” and “very unfortunate,” John Spears became mired in debt, and all his creditors successfully sued him for recompense. The sheriff seized his and Mary Ann’s property, including the slaves who were supposed to be her sole and separate possession, and scheduled a date to sell them to the highest bidders. Mary Ann asked the court to remove John as trustee of her property because he was “not a suitable person to act as trustee f0r her in relation to said property.” She also asked the court to enjoin John’s creditors from selling or disposing of her slaves and return them to neutral parties. The court awarded the injunction and ruled that it “be made perpetual.” The court also ruled that John’s creditors would be “forever enjoined and restrained from selling or in any manner interfering with the slaves set forth and described in [Mary Ann Spears’s] bill” and decreed that Mary Ann would hold the slaves she had inherited “as her separate estate.” The creditors were ordered to pay the costs of her suit.66

It is important to acknowledge that not all husbands relished their roles as their wives’ trustees. Mary Jane Taylor, who possessed a large estate consisting of eighteen enslaved people, 580 acres of land, twenty thousand dollars, “and other things,” entered into a marriage agreement that appointed her husband, Thomas, as her trustee. After managing his wife’s property for a short time, Thomas decided that he no longer wanted to do so. Mary Jane and Thomas asked the court to relieve him of his duties and appoint Warren D. Wood in his place. The court granted the couple’s request.67

When husband-trustees proved themselves inept, women were not reticent about going to court to relieve them of these duties, removing their slaves from their husbands’ control, placing them in another person’s care, and recouping the profits that their property yielded. Elizabeth Duncan had no qualms about bringing her concerns to court. Petitions like hers offer a strong challenge to the view that southern households were monolithically patriarchal. Before Elizabeth’s marriage to William Duncan, she possessed a personal estate that included a thirty-year-old enslaved woman named Mariah, along with Mariah’s two young children, a twenty-year-old enslaved woman named Rany, an eighteen-year-old enslaved youth named Haden, and a sixteen-year-old enslaved youth named Williamson. Over the course of her marriage, her female slaves reproduced prolifically and increased her slaveholding from six to fifteen people. Her husband-to-be, on the other hand, was facing bleak pecuniary circumstances. According to Elizabeth, William was “not the owner of any negro property,” was “poor and without any means,” and already had a “large family on his hands to support.” Despite knowing about William’s financial troubles, Elizabeth still placed her slaves under his management in the hope that he would “increase the same by the purchase of other negroes and property.” She soon discovered how wrong that decision was.68

William managed his wife’s estate “in such a careless negligent and improvident manner” that he was “compelled to sell seven” of “the most valuable” slaves Elizabeth owned. She sued her husband and petitioned the court to remove him as trustee of her estate and appoint another to replace him. Her decision was largely motivated by her fear that William would “so mismanage” her property that he would “squander and waste away the whole of it,” and she would be left destitute. She further requested that the judge divest “by a decree . . . the title to said negroes and their natural increase . . . out of said defendant,” as trustee, that they “be invested in some suitable person” who would serve in this capacity, and that he declare the “issues and profits” of her property secure “for her support,” “her sole and separate use,” and her “absolute disposal.” Upon her death, the property would revert to William and his heirs. In William’s answer to Elizabeth’s bill of complaint, he confirmed all his wife’s assertions. He even acknowledged that he was “not a good manager” and that if his wife or “her trustee” could “manage the property better” than he had done, he was willing to relinquish his role. He admitted that it would in fact be “equitable” for a decree ordering his replacement to be made. The court granted Elizabeth’s request.69

A husband’s violation of his wife’s property rights served as the catalyst for many a woman’s decision to enter a chancery court and petition for relief. But it was just as common for married women to sue their husbands’ creditors when these individuals seized enslaved people who rightfully belonged to them in order to pay their husbands’ debts. Rachel Thompson’s experience typifies the willingness of some married women to fight for their property. Her father, William Smith, had given her two slaves as a gift, and he specified that the title was to be vested “in her alone.” He also stipulated that “her husband . . . would not thereby acquire any property therein,” and that Rachel’s slaves “would not be liable for any contracts entered into or thereafter to be entered into” by her husband, Samuel. He also forbade Samuel to have “any control or right . . . over said negroes.” Smith drew up a deed confirming this, gave the document to Rachel, and “repeatedly stated to his friends” that he had given these enslaved people to his daughter as her own separate property in order to “prevent them from being sold” to pay Samuel’s debts and to prevent Samuel “from disposing of them in any manner whatever.” Samuel acquiesced in his father-in-law’s wishes and routinely “disclaim[ed] having any right, title or claim” to Rachel’s slaves; he frequently “represented [the] negroes to be the separate property” of his wife. Nonetheless, Samuel’s creditors levied upon Rachel’s property to satisfy the debts he owed them.

Rachel Thompson petitioned for a “trial of the right of property” and lost. Undeterred, she appealed, arguing that making her slaves “liable to be sold in satisfaction of [the] said judgment . . . would be contrary to Equity and good conscience.” The lower court’s verdict, she argued, rendered her “without remedy at law,” and as a consequence she would “forever lose her just rights” unless she was “relieved by a Court of Equity where such matters are properly cognizable.” She asked the judge to “inquire into the truth of the facts,” and after assessing them issue “a perpetual injunction” restraining Samuel’s creditors from selling her slaves and “staying all other and further proceedings” upon the judgment until he could make his ruling. On May 12, 1842, Rachel Thompson got her injunction, and she kept her slaves.70

Many of these petitioning women possessed an extraordinary command of the laws governing their property, much more than they were likely to have acquired in isolation, and their petitions sometimes documented their consultation with others who possessed a deeper understanding of the issues they sought to resolve. Many of these women decided to appeal to the courts only after they sought advice from their neighbors and friends. Some married women had the good fortune of knowing justices of the peace, and they drew upon these jurists’ legal knowledge and the advice of their colleagues for help in working through the details of their cases. Others entrusted their legal affairs to their families, while still others may have consulted guides such as George Bishop’s 1858 handbook, Every Woman Her Own Lawyer: A Private Guide in All Matters of Law, of Essential Interest to Women, and by the Aid of Which Every Female May, in Whatever Situation, Understand Her Legal Course and Redress, and Be Her Own Legal Adviser. But regardless of where they acquired their understanding of their “rights,” petitioning women used this information to protect their slaves from their husbands and reclaim the property they deemed to be their own.71

The friends of betrothed women also played a vital role in helping them circumvent the possible pitfalls of marriage and develop ways of dealing with those that could not be avoided. As Margaret Witherspoon prepared to marry Edwin Mason, she consulted others about the match, and it was “by the advice of her friends” that she decided to devise a marriage contract. Before her marriage, Witherspoon was not “well acquainted” with Mason’s “business capacity,” and this ignorance probably goaded her to hammer out the legal details of her marriage arrangement in case he proved to be improvident. Witherspoon’s “memorandum,” as she called it, stipulated that she “retain the possession” of her property and have it “exclusively under her control.” The contract protected her real estate, slaves, and other personal property from any debts her husband incurred. Margaret Witherspoon possessed property in her own right, derived in part from the estate of her first husband. Her friends probably underscored that she needed to secure that property before she married Mason. If she did not, her new husband might squander her wealth and leave her and her children destitute. Or he might be prejudiced against the children from her first marriage, deny them their rightful inheritances, and favor his own children. Historians often interpret marital contracts, separate estates, deeds, and trusts as legal instruments that family members used to protect their financial legacies. But Margaret Witherspoon’s case demonstrates that friends and allies also played important roles in the decisions slave-owning women made about marital agreements. Once an affianced woman settled upon such protective measures, her advisers might have taken part in familial decisions to establish separate estates and deeds of gift, as well. These legal instruments, therefore, were not simply a reflection of familial financial self-interest; they were a product of collaborative efforts on the part of kin, friends, and the heiresses themselves.72

As these cases have shown, women who filed bills of complaint against their husbands and others in chancery court typically did so on the strength of legal documents that had been drawn up, duly recorded, and filed in a county courthouse. But some women who sought legal remedy had entered into oral or “parol” agreements with their husbands. Others conducted their business as though a legal agreement were in place, and when their husbands and communities acknowledged their ownership of separate property through tacit or explicit consent, courts upheld these kinds of “contracts” as well.73

When individuals did not attempt to infringe upon women’s property rights, such oral agreements between spouses and agreements that parents failed to formalize before or after their daughters married probably remained out of the courthouses. The lack of documentation makes it difficult for us to determine with any degree of certainty how many women drew upon these protective measures and exercised the control that informal oral contracts afforded them. However, closer examination of those who did take their cases to court and the positive outcomes of the petitions explored here reveal that the impact of the common law upon the lives of married women, especially the legal doctrine of coverture, was not as absolute or as constraining as many historians have claimed.

Historians such as Sara Brooks Sundberg have contended that propertied women fought as hard as they did and in the ways that they did because they saw their property as part of a familial legacy that needed to be preserved for their children. Sundberg argues that women exercised their rights over property “because they shared their husbands’ interests in protecting and advancing family property as a necessary component of their families’ economic independence.” This was certainly true for some female litigants. But the petitions of slave-owning women also reveal that their husbands’ interests were often in direct conflict with their own. Furthermore, their children often proved to be the instigators of legal, yet underhanded, attempts to take these women’s slaves from them. These women faced extraordinary challenges when they held legal title to property. In addition to husbands, married women’s fathers, brothers, sons, and nephews often attempted to infringe upon their property rights. This was especially true for women who struggled with some form of illiteracy. Many women could only place a mark, instead of a signature, on the petitions and the documents they submitted as evidence of their legal title to enslaved people. Such women relied heavily upon family members to help them preserve their investments in slaves, and those same family members sometimes betrayed their trust and tried to steal their property.74