“WET NURSE FOR SALE OR HIRE”

On a rather ordinary day, a woman named Mrs. Girardeau was strolling the streets of Charleston, South Carolina, when she suddenly came upon a “good natured healthy looking Negro woman . . . with an infant in her arms.” Mrs. Girardeau happened to know of a friend who was in search of a woman to nurse her baby, so she approached the woman and asked if she “knew of a wet nurse to be hired.” The enslaved woman immediately told Mrs. Girardeau that “she was one herself and was in the hands of a broker for sale.” The enslaved woman also told her that she had given birth to “many children,” and she was “therefore somewhat experienced in the care of them.” Mrs. Girardeau relayed this information to her friend, and the new mother, her husband, and the couple’s agents immediately arranged to purchase the enslaved mother and her infant.1

Through parlor talk, or perhaps by a passing mention in a letter from a friend, Mrs. Girardeau had learned that a mother was in need of an enslaved woman to suckle her baby, and she was able to assist in finding one. Everything that Mrs. Girardeau did that day—approaching and questioning the enslaved woman about her qualifications to perform a certain kind of labor, determining that she would be suitable for that purpose, and passing along the information that would facilitate the purchase—characterized the typical transactions that unfolded every day in slave marketplaces throughout the South. And like many of those sales and purchases, this transaction did not start in the brick-and-mortar slave market. It began in a southern household, moved into the street, was finalized in a slave trader’s establishment, and ended with an enslaved woman moving to a new slaveholder’s home to breastfeed a white child.

As this incident suggests, white women, especially mothers, were instrumental in these kinds of market transactions. They routinely sought out and procured enslaved wet nurses to suckle their children, creating a demand for the intimate labor that such nurses performed in southern homes. They were crucial to the further commodification of enslaved women’s reproductive bodies, through the appropriation of their breast milk and the nutritive and maternal care they provided to white children. The demand among slave-owning women for enslaved wet nurses transformed the ability to suckle into a skilled form of labor, and created a largely invisible niche sector of the slave market that catered exclusively to white women.

The intersection between slave markets and southern households can shed light on the formal as well as informal markets through which enslaved mothers circulated. It also enables us to examine white women’s investments in these markets and the roles they played in creating them. And such an exploration reveals details about southern slavery which challenge characterizations of skilled enslaved labor as largely performed by men.

The labor that enslaved wet nurses performed remains relatively invisible in historical studies of American slave markets and scholarship about southern motherhood. When scholars do address the issue, they discuss these women in ways that do not fully account for how they circulated within southern households, communities, and the slave market. Even though white mothers routinely sought out and procured enslaved wet nurses to suckle their children, scholars of the slave market and trade generally ignore the roles they played in the transaction. A recent study contends that it was white men who were largely responsible for converting enslaved women’s breast milk into “capital.”2 The consensus among historians holds that white elite and middle-class mothers tended to use enslaved wet nurses only as a last resort, not because they were readily available.3 Sally McMillen, for example, quantified infant feeding practices for the years 1800–1860 and found only seventy-three comments about the subject in her selected sources, which were primarily elite women’s diaries and personal correspondence. She concluded that 20 percent of these women used wet nurses. She also argued that enslaved women rarely attested to serving as wet nurses, and she pointed to this as further evidence that white women rarely used them in this way.4 Such a small sample of documents, however, particularly those that well-to-do, literate women left behind, does not tell us much about the practice among the non-elite white women who made up the female majority living in the South during this period. Many formerly enslaved people, not just enslaved women, remarked upon white mothers’ use of enslaved wet nurses, and they used a range of terms—“nuss,” “suckle,” “titty”—to describe wet nursing in their testimony. They also used the term “breast” interchangeably or along with these terms. A more nuanced examination of their testimony that includes all the WPA interviews—rather than simply the interviews with women who personally served as wet nurses—and that bears their more complex terminology in mind, reveals that enslaved people talked about the practice of wet nursing far more often than McMillen claimed. Even when they described enslaved women serving as “nurses” to white infants, they made it clear to their interviewers that wet nursing was the kind of nursing about which they spoke.

It is equally important to acknowledge that the questionnaire that the WPA’s National Advisor on Folklore and Folkways developed did not include any questions about slave owners’ maternal or parenting practices, nor did it include specific questions about the practice of wet nursing. This might explain why a formerly enslaved person would neglect to mention the practice in an interview.5 The alleged scarcity of such testimony might also be explained by the fact that the WPA writers interviewed only about 2 percent of the formerly enslaved people who were still alive in the 1930s.6 It is likely that formerly enslaved people neglected to mention wet nurses or wet nursing during their interviews because the nature of the questions did not goad them to do so, and a larger sample of formerly enslaved interviewees would have produced more references to the practice if the writers had been able to locate these people and record their testimony.

In the nineteenth century, the use of enslaved African American wet nurses by white southern women was troubling to outsiders, and to some southerners as well.7 However, their discomfort did not arise because wet nursing was an unusual practice. Mothers have placed their infants at the breasts of other women since antiquity.8 Moreover, in her study of the cultural significance of nursing and infant caregiving in early modern England and British North America, Marylynn Salmon discovered that people of European descent used breast milk for a host of medicinal purposes because they believed that it “possessed a life-giving force.”9 In this way, the milk that mothers produced served a communal good. Whether this assumption characterized how Anglo-Americans understood enslaved women’s breast milk in the eighteenth century is unclear. What is clear, however, is that by the nineteenth century, Anglo-Americans had grown increasingly concerned about the power of bodily fluids and a child’s ability to imbibe moral and racial essences through a woman’s breast milk. Fears of contamination served as the basis for stern warnings to new mothers about putting their babies at the breasts of strange women. Medical professionals and authors of maternal and infant advice literature strongly encouraged mothers to assume complete responsibility for nursing their own children. They cautioned them against delegating this task to other women or feeding their infants by bottle and other “unnatural” methods. And they summarily shamed mothers who chose not to take their advice.10

Such attitudes are particularly important when considering the matter of cross-racial and cross-ethnic wet nursing. In the nineteenth century, as the United States witnessed unparalleled waves of European immigration, and as nativist fears influenced the attitudes of American-born whites toward the people entering the country’s major urban centers, male physicians and “scientists” embraced this problematic understanding of breast milk with renewed fervor. They cautioned American-born white mothers against sending their children to immigrant women to nurse because breast milk served as a means by which women passed their traits on to their infants.11 The association between breast milk and moral and physiological contagion spread throughout the South and faced southerners with a peculiar paradox: if breast milk carried the racial and moral essence of the lactating mother, and African Americans were morally and biologically inferior beings, what would be the fate of the white children who suckled at the breasts of the enslaved? Many white southern women thought of their own fragile health, which prevented them from nursing or producing an adequate milk supply, and decided that using a wet nurse was essential, regardless of their repulsion. Other white southerners decided that the bound condition of enslaved wet nurses was the problem, not their race. A formerly enslaved man named John Van Hook claimed that in the part of Georgia where he resided, “It was considered a disgrace for a white child to feed at the breast of a slave woman, but it was all right if the darkey was a free woman.” John’s great-great-grandmother Sarah Angel earned her freedom because of this aversion. A member of the Angel family needed a wet nurse, and since Sarah Angel was nursing a child of her own, the family chose to use her. They did not want Sarah to sleep in the slave quarters while she was feeding the white baby, so they freed her.12

Most slave owners were not so generous. On some plantations, like the one where Peggy Sloan was raised, slave owners “had a woman to look after the little colored children, and they had one to look after the white children.” Sloan’s owners charged her enslaved mother with wet nursing the white infants, though despite the racial division in maternal care, her mother was permitted to suckle her along with her mistress’s children. The owners did not free Sloan’s mother so that she could perform this labor, however.13

White southern mothers grappled with the paradox of cross-racial wet nursing by prioritizing the health of their infants over all else and subordinating the needs of enslaved women and their children in the process. These white women were instrumental in creating a market for enslaved wet nurses’ labor. In doing so, they helped augment the potential value of enslaved women within southern slave markets more broadly.

While white mothers routinely expressed a desire to nurse their own children, many were ill or too weak following childbirth and could not nurse or could do so only with great difficulty.14 Newspapers targeted women who experienced those difficulties with advertisements like the one captioned “Sore and Swelled Breasts” that appeared in the Ripley Advertiser: “Since the invention of Bragg’s Arctic Liniment,” the ad proclaimed, mothers no longer were obliged “to transfer their infant children to the care of a wet nurse,” if their own breasts “should be sore or swollen”: “All that is necessary, is to procure some of Bragg’s Arctic Liniment and rub the affected parts with it, gently, for a few times, and the evil is remedied.”15 Esther Cox, a white South Carolina matron who frequently corresponded with her daughters after they gave birth, advised them on what to do when their bouts of weakness, ailments affecting their breasts, or their infants’ seeming unwillingness to nurse made it difficult to breastfeed. She recommended that her daughter Mary apply a salve to her hardened breasts, a treatment that proved to be a “fine remedy” for another woman experiencing similar problems nursing her infant. However, after a year, Mary still struggled to nurse her child.16

Blocked milk ducts and breast infections could endanger the lives of nursing mothers. Such complications could even require a surgical intervention that involved removing portions of the breast.17 Faced with these circumstances, women often had little choice but to call upon other women, who were often enslaved, to care for their infants, a practice referred to as “mercenary nursing” in nineteenth-century Brazil.18

Formerly enslaved people described the circumstances that would lead a white mother to use an enslaved wet nurse for her children, and their recollections support the argument that some white women were too ill or physically unable to nurse their infants following childbirth. As white mothers recovered from the effects of childbirth, enslaved women provided nutritive care to their infants.19 Other white mothers could not nurse their own children because of insufficient milk production or because their infants could not suckle.20 But maternal unfitness or fractious infants alone did not explain the prevalence of enslaved wet nurses among white southern families.

Formerly enslaved people such as Rachel Sullivan claimed that the use of enslaved wet nurses for white infants was a widespread practice. According to Sullivan, “All de white ladies had wet nusses un dem days.” Betty Curlett believed that other women used wet nurses for purely aesthetic reasons: “White women wouldn’t nurse their own babies cause it would make their breast fall.” Some white mothers, such as Jane Petigru, cited convenience: she had a “distaste for” breastfeeding her own infants because it made her “a slave” to her children.21 Her reluctance becomes more understandable in light of the number of children southern mothers bore in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Historians estimate that women in the Old South on average gave birth to between five and twelve living children during their lifetimes.22 Formerly enslaved people described their own mothers being tasked with feeding all their mistresses’ children even when nothing prevented their mistresses from doing so themselves. Mary Jane Jones claimed that her mother “would have a baby every time my mistress would have one so that my mother was always the wet nurse for my mistress.” Eugenia Woodberry breastfed all of her mistress’s children, too.23 Mattie Logan recalled that her mother, Lucinda, “nursed all Miss Jennie’s children because all of her young ones and my mammy’s was born so close together.” Logan thought this arrangement was “a pretty good idea for the Mistress, for it didn’t keep her tied to the place and she could visit around with her friends most any time she wanted ’thout having to worry if the babies would be fed or not.” In order to expedite this labor arrangement, Lucinda’s mistress had a two-room cabin built behind the main house, away from the other slave quarters, for Lucinda and her family.24

The practice of using enslaved women as wet nurses placed increasing physical demands on them. Enslaved mothers were generally deprived of adequate food and nutrients to support and sustain their own health, much less that of two or three babies, and white mothers dealt with this difficulty as they might any other household problem. The slave owner Ella Gertrude Thomas used a number of enslaved wet nurses to feed her children, and when one woman could not produce enough milk for Thomas’s infant and her own, she would replace her.25

As this testimony suggests, in some households, breastfeeding simply constituted another form of labor that slave owners required enslaved women to perform. For Warren Taylor’s mother, nursing white children was one of her primary jobs. Nursing white children was the only work that Mary Kincheon Edwards performed during slavery.26 These recollections make it clear that enslaved women were giving birth on a routine basis. But what often remains unexplored is what led to these constant conceptions. While enslaved women performed the most arduous forms of labor in their owners’ fields and households, they also had to conceive, carry a pregnancy to full term, give birth, and lactate in order to be able to serve as wet nurses. Sources suggest that this is precisely what happened. Some of the enslaved women’s children were undoubtedly conceived within relationships of love, but others were undoubtedly the result of sexual assault.

John Street was a married slave owner who also ran a business in which he held slaves and then sold them to slave dealers. Louisa Street, one of the enslaved women he owned, conceived three children by him: Amy Elizabeth Patterson and her twin sisters Fannie and Martha. Street’s wife gave birth to an infant around the same time that Amy Elizabeth was born. In her interview, Patterson alluded to the fact that she was a child born of violence and that her mistress “knew the facts” surrounding her conception. Despite this knowledge, her mistress gave her white child to Louisa to nurse alongside Patterson, a decision that must have added to the psychological trauma Louisa Street suffered after the rape.27

Mary Kincheon Edwards, formerly enslaved woman who served as a wet nurse (Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1938, Digital Collection, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

Similarly, Emily Haidee, a white Louisiana woman who owned Henrietta Butler, forced Butler to have sex with a man on her plantation. The assault perpetrated against Butler resulted in pregnancy, and she gave birth to the child, who died shortly thereafter. While she mourned the loss of her baby, Haidee made Butler suckle her own infant.28 Violence, loss, and separation often characterized the experiences of enslaved mothers who were compelled to serve as wet nurses to their owners’ children.

Many white southern mothers seized upon the chance to develop their maternal bond with their infants by nursing them. Others employed enslaved wet nurses routinely, not simply as a last resort, even though they knew that other white southerners were averse to, if tolerant of, the practice. Ellen Vaden’s enslaved mother nursed both her and her mistress’s infant son Tobe. But “when they had company, Miss Luisa was so modest she wouldn’t let Tobe have ‘titty.’ He would come lead my mother behind the door and pull at her till she would take him and let him nurse.” This incident lays bare some of the ways in which white children came to understand the social mores of slave-owning communities. Tobe was young enough to nurse, but old enough to understand that suckling at an enslaved woman’s breast in public or in the presence of company was unacceptable.29

While some white mothers, like “Miss Luisa,” hid their reliance upon enslaved wet nurses from their friends and neighbors because of modesty or communal mores, others were not so bashful. Rachel Sullivan’s owners allowed a white mother visiting from Russia to use her aunt as a wet nurse while she stayed on their plantation. Sullivan knew about this firsthand because her owners made her serve as the dry nurse to her infant cousin in her aunt’s absence.30

Formerly enslaved people’s remembrances do more than merely affirm that white mothers used enslaved wet nurses or touch on the motives behind their decisions. It is no minor point that the children and grandchildren of enslaved wet nurses offered much of the testimony about the practice, for they were the individuals most deeply affected by these women’s constant absences or, in some cases, complete separation from their children. The people who owned T. W. Cotton and his family, for example, compelled his mother to nurse their infant son Walter. Her work left Cotton in the care of his grandmother, who fed him animal milk or pap from a bottle, a dangerous practice that many physicians strongly discouraged at the time.31 Formerly enslaved people spoke of the painful separations of nursing mothers from their enslaved kin, and although these severances did not occur in formal slave markets, the marketplace nevertheless shaped them.

Historians have also examined the commodification of maternal labor and the wet nurse marketplaces in the United States, but their studies focus primarily upon markets in the North rather than the South. Such studies are nonetheless useful for understanding the contours of the southern wet nurse marketplace and identifying key differences between the markets in these two regions. The historian Janet Golden describes an informal northern market in which white parents would seek out and procure wet nurses by word of mouth through familial and communal networks. She also uncovered an urban “marketplace”: a labor network in the North in which free white women—often poor immigrants, single mothers, or “wayward” or “fallen” women—were the primary providers. This marketplace was particularly active from the 1850s to the 1870s. It depended upon medical referrals and employment recommendations and involved a number of public facilities, intelligence offices, and benevolent organizations that gradually institutionalized the use of wet nurses and offered these women’s services to parents of all social classes. It was largely organized by “patterns of immigration, ethnic stereotypes, and racial prejudice, as well as medical thinking and local domestic practices.”32

Golden argues that “the wet nurse marketplace . . . responded not only to the creation of new sources of supply but also to shifting levels of demand,” and newspapers proved crucial to recruitment. In a review of northern newspaper advertisements, she identified a distinct vocabulary that characterized the wet nurse marketplace, one that served as a “kind of shorthand” and “combined the vernaculars of medicine and domestic service.” It “emphasized four qualities: good health, upstanding character, plentiful milk, and milk that was fresh,” and individuals incorporated such phrases when they placed ads for their ideal wet nurses.33 Wet nurse advertisements “exposed the real economic value of mothers as producers” because “employment of a wet nurse provided needed income for poor mothers,” while “for middle-class and elite families, the hiring of a wet nurse replaced the productivity of the mother.”34 In the South, the use of enslaved wet nurses’ bodies and the circulation of these women through the region’s slave markets present other ways to understand the economic dimensions of maternal labor in the nineteenth century.

In the context of slavery, the southern wet nurse marketplace operated differently from the northern one. The institution of slavery permitted slave owners, slave traders, and prospective hirers and buyers to manipulate and examine the bodies of enslaved women in ways that were unavailable to white parents in the North. Many laws regarding slavery allowed owners to ignore an enslaved mother’s desire to nurse and raise her own children. And white southern women were among those who took full advantage of their access to enslaved women’s bodies and labor. These women were instrumental in creating a market for enslaved wet nurses, determining how such women would be employed, and seeking them out within and beyond the walls of the slave yard.

Southern women constructed and participated in an informal market network of family and friends from within their own homes, and they relied on this network for information about enslaved wet nurses who might be available. The market was informal in the sense that it was contingent upon the circulation of wet nurses largely outside the brick-and-mortar slave market, and it did not usually involve the exchange of currency, although money did occasionally change hands. Rather, this informal market resembled other female-dominated systems of barter and exchange that characterized early American households.

It was common practice for women in the North and the South to support their families by bartering and exchanging home-produced goods and foodstuffs with other women in their communities, and in similar ways, white women routinely borrowed enslaved people from and lent them to one another.35 They were in essence bartering and exchanging enslaved wet nurses as living goods, and in this context, enslaved mothers could be transferred from one person to another without diminishing their value in the formal slave market. Unlike other barter exchanges, these white women did not “produce” enslaved wet nurses through their own labor, but they did claim ownership of their bodies and the products of wet nurses’ labor—their breast milk. The narratives of enslaved people and slave-owning women’s personal letters and diaries attest to the existence of this informal market. And its informality has generally obscured it from historians’ view.36

An advertisement that Sophia Young submitted to the Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser suggests another possible reason this market has escaped our attention. Young was a midwife who practiced her craft in the Baltimore, Maryland, area, and in her ad she notified potential clients that she had relocated. She also wanted them to know that “a good Wet Nurse [could] be heard of by applying to her.” Midwives were the principal individuals involved in women’s and infants’ care during childbirth in the colonial era and much of the nineteenth century, and they offered their clients medical advice and passed on pertinent information about childcare. Young’s aside about the availability of “a good Wet Nurse” suggests that this kind of information might have circulated among other midwives and the mothers they assisted, obviating the need to advertise for such help.37

The women who supplied enslaved wet nurses capitalized on their informal connections in order to procure other kinds of enslaved laborers, as we can see from a case involving two Saint Landry Parish, Louisiana, residents. During the summer of 1827, Elizabeth Patterson hired out an enslaved woman named Becky to George Jackson’s wife as a wet nurse for her young son. Patterson initially offered Becky’s services “gratuitously” because the enslaved woman “was of no use” to her. Patterson reasoned that by hiring Becky to the Jacksons, she would be spared the expense of caring for her. Mrs. Jackson apparently informed her husband about the proposal, but he “was unwilling to accept the services . . . without paying for them.” Mrs. Jackson went to Patterson’s plantation the following day, and Patterson once again proposed that she take the enslaved woman, whom she agreed to hire out “for six or seven dollars per month.” Mrs. Jackson and her husband accepted the offer. After Patterson finalized the deal with the Jacksons, she in turn hired three enslaved men from them to work her sugar plantation during the 1827 and 1828 grinding seasons.38 These negotiations illustrate how slave-related transactions might unfold outside the formal marketplace. They also highlight the roles white women, especially new mothers, played on both ends of these transactions. Moreover, they underscore the equivalence between field and maternal labor, two kinds of work that are often categorized quite differently, and the value slave owners placed on each. Here, we could say that the labor of one wet nurse was considered equivalent to that of three field hands.

There were parallels between the formal wet nurse marketplaces in the North and South, but there were also important divergences. Whereas the formal wet nurse marketplace of the North involved agencies and organizations that profited from the labor of free white women, advertisements posted in southern newspapers establish direct connections between the wet nurse marketplace and the slave market. As the historian Frederic Bancroft observed, the “slave wet nurse was a peculiar but not rare commodity,” and “she could, if buxom, spare one ample breast for the profit of her owner.” Furthermore, if she was “of good character and appearance, she was at a premium.”39

Thousands of advertisements for wet nurses appeared in southern newspapers throughout the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. In a sample of fifty-seven nineteenth-century newspapers published in Alabama, Washington, D.C., Maryland, Virginia, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Florida, Missouri, Mississippi, and Tennessee, individuals placed 1,322 advertisements for wet nurses between 1800 and 1865. In close to 300 of those advertisements, individuals placed “Wet Nurse Wanted” or “Wet Nurse Wanted Immediately” advertisements, wording which highlights the demand and often urgent need for these women’s labor. In these ads slave owners and potential hirers actively sought out “colored,” “negro,” and enslaved women within slave-hiring markets throughout the South.

These advertisements also reveal the vibrant hiring market that white southerners created in order to fulfill the demand for enslaved women’s maternal labor. Women were key to defining the contours of this market because they were ultimately responsible for deciding which wet nurses would best serve their infants’ needs; they were the primary hirers and the only laborers. Yet many historians still describe the southern slave-hiring marketplace as a male purview.40

Women entered slave-hiring markets to obtain both enslaved wet nurses and other kinds of enslaved laborers. In the small town of Mount Sterling, Kentucky, the buying, selling, and hiring of enslaved people took place at ten o’clock in the morning on New Year’s Day.41 This was a highly public family and community affair in which the sale, purchase, and hire of enslaved people took place among “throngs” of men, women, and children. Such transactions were not confined to or bound within the slave yard; some took place in the streets. The people who “flocked from various parts of the country” represented every stratum of society, including African Americans, and attendees represented all age groups. As the author and educator William Henry Venable walked through the crowd, he overheard one enslaved woman express dismay about the white woman who had just agreed to hire her. She was crying because it had “fallen to her lot to serve a mistress whom she feared.” Venable’s account not only suggests that women were present at public events where enslaved people were hired and sold, it also reveals that they were active participants. What is more, this enslaved woman’s lamentations indicate that her new mistress may have routinely hired enslaved people because she had acquired a reputation among slaves for being difficult to please, or even cruel, and they circulated this knowledge among themselves.42

While the southern market in enslaved wet nurses was primarily a hiring one, white mothers’ demands for these women eventually led to the development of a niche sector of the slave market in which individuals offered wet nurses for sale. Men such as Robert Hill and firms like R. M. Montgomery and Company also sought out enslaved wet nurses to purchase for their families or on their clients’ behalf. On two separate occasions, Brian Cape and Company offered enslaved women and their children for sale and noted the mothers’ ability to serve as wet nurses. Even when the nation was in the throes of civil war, J. W. Jordan, Sr., of Renwick, Georgia, placed an advertisement in the Macon Daily Telegraph through which he sought to “buy or hire” a “young, healthy, and intelligent” enslaved wet nurse. Other advertisements informed interested subscribers that they could buy or hire the enslaved wet nurses mentioned.43

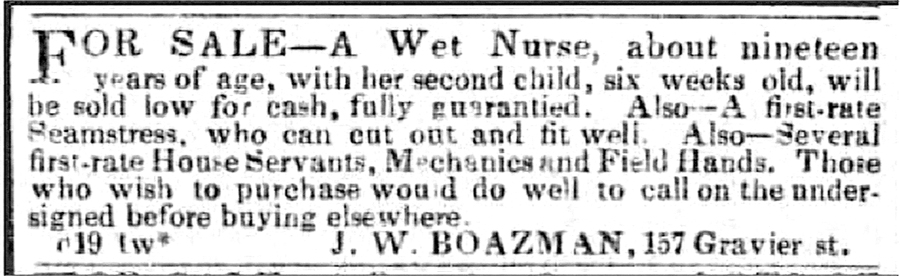

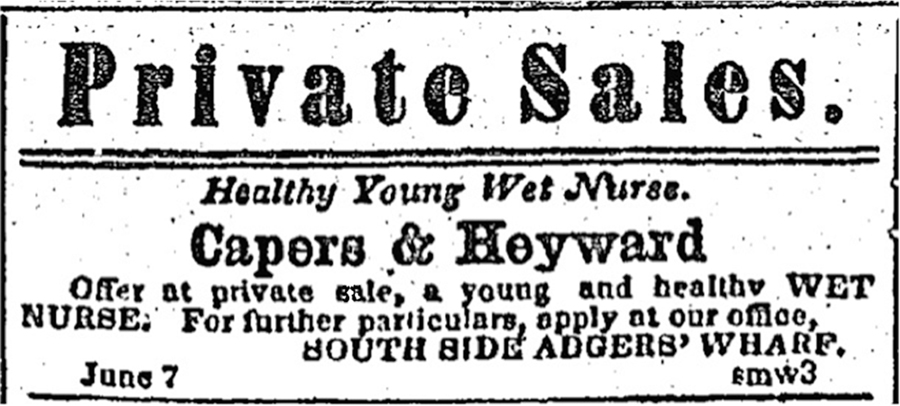

Slave traders were responsible for placing most of the advertisements related to selling, rather than hiring, enslaved wet nurses. The well-known New Orleans slave trader James W. Boazman placed an advertisement in the Daily Crescent in which he offered “a wet nurse, about nineteen years of age, with her second child” for sale. He planned to sell them both at a “low [price] for cash, fully guarantied”—that is, they were free of any ailments that might impair their function or value. Hundreds of miles away in Charleston, South Carolina, the slave-trading firm Capers and Heyward placed an advertisement in the Mercury in which they offered an enslaved wet nurse for private purchase.44 Male slave traders may have dominated these advertisements as the purveyors of enslaved wet nurses, but they placed them with an eye toward a female clientele.

As in the northern marketplace, individuals in the southern market emphasized good health, upstanding character, and plentiful, fresh milk when they sought or offered the services of enslaved wet nurses. A typical advertisement, for example, would request “a healthy Negro woman, with a fresh breast of milk, to suckle and nurse an infant child.”45 But one important difference distinguished the language used in the southern marketplace from that in the North. Southern advertisers not only used the vernaculars of medicine and domestic service to describe their “wares,” they drew upon the lexicon of the slave market.

Wet nurse ad submitted by slave trader J. W. Boazman, Daily Crescent, December 21, 1850 (Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress)

Capers and Heyward newspaper ad for private sale of enslaved wet nurse, Charleston Mercury, June 7, 1856 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

Terms such as “likely,” “good,” “excellent,” and “superior,” and phrases like “first rate” and “No. 1,” allowed slave traders to assign value to the bodies of the individuals they advertised by placing these slaves within “saleable lots.” They also enabled slave dealers to place enslaved people in racial categories, and the terms and phrases they used came to signify the ideal characteristics prospective buyers sought in enslaved people. Traders often emphasized that the enslaved people they hoped to sell were “sound” in mind and body and were thereby healthy and free from injury or disease. The characters and personal histories of enslaved people were equally important factors to those selecting them.46

When white southerners were in the market for enslaved wet nurses or when ordinary folks hoped to sell them they used the terminology of the slave market. Thomas Theiner, for example, placed an advertisement in the Charleston Mercury that offered “a likely colored wet nurse, 17 years old” for hire. A Richmond area agent and collector named O. H. Chalkley announced that he had a “superior wet nurse” who was of “first rate character” on hand for anyone interested. Other southerners sought wet nurses who were “neat and sound in body and reputation.”47 None of these qualifiers or phrases would strike southerners as strange, especially in regard to buying or hiring enslaved laborers. The individuals who placed these ads also understood that white mothers would be equally familiar with these terms and phrases as well as with their coded meaning.

In the context of southern slave markets, enslaved mothers’ breast milk was a commodity that could be bought and sold, and buyers and sellers recognized these women’s ability to suckle as a form of largely invisible yet skilled labor. The conception of what constituted “skilled labor” in general use among scholars is far too narrow to account for the kind of work that enslaved women performed or the prices they commanded when exposed for sale. Furthermore, it does not take into account the computational logic white southerners used to assign value to certain types of labor or the ways gender shaped their appraisals. Georgia slave owners not only assigned significant value to the kinds of labor women performed every day—work that historians do not typically define as “skilled”—they differentiated among levels of skill in their routine tasks and appraised the value of enslaved women accordingly.48 Wet nursing was a kind of work that only women could perform, and more often than not white mothers were the ones who assessed enslaved mothers’ levels of skill and efficiency. As with other kinds of labor, breastfeeding required certain qualifications and skills: women had to be physically capable of nursing children, they had to learn how to breastfeed, and they needed to refine their skills over time. Some mothers could not nurse children, and some were more adept at it than others. This might prove especially true when we consider the impact of environmental factors such as diet, previous illness, or problems during pregnancy. All these factors could adversely impact an enslaved woman’s long-term health, her ability to produce plentiful milk supplies and avoid medical conditions associated with nursing such as mastitis, and ultimately, her ability to be an effective wet nurse. Historians who view nursing a child as “natural” rather than a form of skilled labor ignore the view of the white mothers who sought the services of enslaved wet nurses, of the enslaved mothers themselves, and of the men and women who sold and hired out enslaved mothers for this purpose, all of whom most certainly saw it as such. Individuals in need of a wet nurse often sought enslaved women who had previous experience breastfeeding white children, and southerners who had such women to sell or hire made sure to remark upon their experience in their advertisements. In a number of such advertisements, owners indicated that the enslaved mothers they sought to hire out were “accustomed to attending to white children,” were “well experienced in that line” of work, had served as wet nurses “in the most genteel families,” or had previously “given suck to a white child.”49

White southerners not only assessed enslaved women’s level of skill by determining whether they possessed previous experience, they also evaluated and graded the quality of enslaved women’s milk as “young,” “good,” “very good,” “fine,” and “excellent.”50 White mothers assessed the quality of enslaved wet nurses’ milk using factors that included the age of the enslaved woman’s current infant and the number of children she had previously borne. The younger her child, the fresher or “younger” the milk was presumed to be. Occasionally, the milk was labeled with the child’s age, as when an individual in Savannah, Georgia, sought a wet nurse with “milk from six to seven months old.”51 Prospective buyers and vendors also judged the quality of the milk by determining whether the children the mother was nursing were thriving. An advertisement in the City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser of Charleston stated that the enslaved mother on offer for hire had “given suck to a white child for a short time past, who is very healthy.”52 In her chance encounter with a wet nurse, Mrs. Girardeau had visually examined the “fine healthy looking infant” in the enslaved mother’s arms as she conversed with her on the street. Based on the enslaved mother’s previous experience and the conclusions Girardeau drew about the health of the woman’s infant, Girardeau determined that the woman might suit the needs of her acquaintance, and she was right. Ella Gertrude Thomas, who had employed a number of wet nurses, also determined that Georgianna, her enslaved wet nurse at the time, was suitable once her son “commenced to fatten.”53

Prevailing scholarship that focuses on “skilled” enslaved labor does not attend to this particular kind of labor or the systems that southerners used to evaluate and grade it. In his global history of cotton and capitalism, Sven Beckert argued that “the logic of capital” was forced upon “the logic of nature,” a process that changed “the way the cotton plant itself was seen.” The same could be said about breast milk, which was, like cotton, a product of nature that enslaved people cultivated and produced and white southerners sold. Just as cotton growers created grading systems that informed interested parties about the quality of the cotton for sale, white southerners developed a system by which to inform potential buyers and hirers about the quality of enslaved women’s breast milk.54 Enslaved wet nurses nurtured white southern children who would grow up to serve critical roles in the expansion of slavery into the West and Deep South, as well as the exponential growth of southern cotton cultivation in these regions. Their intimate, skilled labor, and the products of that labor, are key to understanding the complicated history of cotton and capitalism.

On occasion, prospective hirers and buyers wanted enslaved wet nurses to do more than suckle white children, and the slave traders, brokers, and slave owners who had such women in their possession knew exactly how to appeal to them. Advertisers touted enslaved wet nurses’ skills as seamstresses, washerwomen, house servants, and ironers or advised prospective hirers that an enslaved female laborer could double as a wet nurse if the need arose.55 The firm Milliken, Primerose, and Company advertised a “valuable young negro wench, about 23 years of age” along with her son, whom they described as a “likely smart boy about 6 years old.” The woman was a house servant but, promised the firm, she “would be valuable as a wet nurse,” too. In the winter of 1820 the Charleston jeweler John Baptiste Duplat similarly advertised “a wench” who was “an excellent house servant, cook, washer and ironer, and a good wet nurse with her infant child” for sale.56 Theodore A. Whitney, a broker and an auctioneer in the Charleston area, was more aggressive as he used bold capital letters to advertise a “wet nurse, seamstress, washer, ironer, and house servant . . . her child about six weeks old,” and a “Boy to attend to it” in the Southern Patriot. He clarified that the woman could “be hired either as a wet nurse, or either of the above capacities,” and he reassured interested individuals that she was “a complete seamstress, washer and ironer, and house servant”—the word complete signifying her ability to perform all of this work adeptly.57

On at least one occasion, an individual advertised an enslaved woman’s ability to serve as a wet nurse before she even began to lactate. This advertiser informed prospective hirers that the enslaved woman was “used to attend[ing] in the house,” but that she would also “answer as wet nurse in a few weeks,” thereby suggesting that she was pregnant and had not yet delivered her child at the time when the ad was placed.58

Very few advertisements mentioned prices for enslaved wet nurses or the wages they earned when hired, and this omission makes it difficult to determine whether they were considered more or less valuable than other enslaved female laborers. Advertisements that do include this information, however, reveal that the labor enslaved women performed as wet nurses could be quite valuable to their owners and costly to those who hired them. In 1803, for example, one individual sought to sell an enslaved woman and her child for six hundred dollars. The advertisement alleged that she was “very fond of children” and “would answer for a wet nurse.” Five years later, Thomas Screven of Hampstead, South Carolina, offered “a healthy young wench, with her child, about three weeks old” for sale. He claimed that she was “fond of children” and “expected [to] make a good Wet Nurse,” thereby implying that she had not yet performed this particular labor. He wanted four hundred dollars cash for the two of them.59 When white southerners hired out, rather than sold, enslaved wet nurses, the owners retained the value of their bodies and repeatedly reaped the pecuniary rewards of their maternal labor. In 1804, an individual who hoped to hire out an enslaved wet nurse indicated that he or she expected to receive ten dollars a month for her wages. Another expected to receive eight dollars a month.60

Concerns about the costs associated with procuring enslaved wet nurses also connote something about their value within the slave marketplace. One white woman, Kitty Harris, had trouble getting her son to nurse, and she suffered from an insufficient milk supply after he began to feed. Her mother hoped that she would persevere, despite the trouble she faced, because she worried that Harris’s young family could not afford to hire or buy a wet nurse.61 Like the Harrises, not all families could afford enslaved wet nurses, and this financial impediment not only presents another reason some women did not employ enslaved wet nurses, it also hints at the considerable value of enslaved mothers’ nutritive labor in slave markets and the South more broadly. Some white southern women left little doubt that they valued the maternal labor that enslaved women performed. After a white slave-owning woman learned that her female slave had been accused of theft by the man to whom she was hired, she ordered him to whip the enslaved female for her crime, but she asked that he “spare her breasts, as she is giving suck to a very young child.”62 Whether this enslaved woman was nursing her own child or a white woman’s is unclear. Nevertheless, her owner assigned immense value to her breasts and the milk that flowed from them.

Court records offer additional evidence of the respect white southerners accorded an enslaved woman’s ability to nurse. Raphaël Toledano emancipated an enslaved woman, Delphine, in part because she had served as “the wet nurse of two of his children.” Samuel Street similarly sought to emancipate an enslaved woman named Delia, because she was “a faithful & attentive nurse to his oldest son.” Street told the court that it was “from her breast [that] his infancy was supported.”63 Other cases, such as one involving an enslaved mother named Mima, offer further clues about the value some white southerners placed on an enslaved woman’s ability to suckle. Jane Gladney owned Mima, and when Gladney died, her will stipulated that Mima should go to her grandchildren. Since they were still minors, the executors of Gladney’s will held Mima in trust until Gladney’s heirs came of age. Gladney’s will required her executors to hire Mima out and use her wages to create two twenty-five-dollar legacies for her grandchildren and to allow any of Mima’s remaining wages to accrue until they reached their majority. After Gladney died Mima gave birth to a son named Isaac, and not long afterward Gladney’s executors discovered that Mima suffered from a “disability of suckling,” which they attributed to the fact that she was “badly burned in her breast” in her youth. As a consequence of this injury, Mima was “unable to give any sustenance or support to her children from the breast.” The executors claimed that they were experiencing difficulty in hiring Mima out because few persons were “disposed to hire” or were “willing or in a situation to furnish milk or provide suitable attendance for raising the children.” In light of these circumstances, Gladney’s executors decided to sell Mima and sought legal permission to do so, and the court granted their request. They sold Mima and her child on January 1, 1838. It is important to note that the executors did not have to sell Mima because of her inability to suckle. Slave owners frequently compelled enslaved women to leave their infants in other enslaved women’s care while they worked in the fields and limited the time they could spend nursing them. They also separated enslaved mothers from their children when they hired them out as wet nurses, a practice that also required enslaved women to nurse enslaved infants who were not their own. Gladney’s executors had at their disposal a number of ways by which they could have solved this problem. Nevertheless, their decision to sell Mima because she could not suckle underscores how important lactation was in the financial calculations slave owners made when ascribing value to enslaved women.64

Wet nurse advertisements like the ones described above highlight a darker dimension of the slave market. Many of these ads reference the loss of an enslaved woman’s child and separation from her newborn infant. In fact, many made it clear that an enslaved mother had recently lost her child or would be hired without the baby. On June 17, 1813, an advertisement appeared from someone who sought to hire out a wet nurse who had “just lost her first child” in the City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser. Five months later, in the same newspaper, another subscriber advertised “a wet nurse” who was a “healthy, young, and sober wench, with a good breast of milk, having lost her child.”65 Far more frequently, those who offered enslaved women as wet nurses said nothing about their children, implying that these mothers had lost them through death, sale, or some other manner.66

There was an important reason individuals mentioned an enslaved mother’s loss in these advertisements: their lack of children was a selling point. Individuals routinely placed advertisements that expressed the desire to hire or purchase a wet nurse without children or, in the common parlance, “without encumbrance.”67 Mrs. Dawson, a Charleston area resident, offered for hire a “healthy black wet nurse, without a child,” and a woman named Mrs. Palmer sought a wet nurse without a child.68 Prospective buyers and hirers recognized that enslaved wet nurses who were accompanied by their children would not be able to devote all their time and milk supply to white infants because they would need to attend to their own. They also realized that separating enslaved mothers from their children could present problems. These potential separations were a “constant point of tension and negotiation” between white families and the enslaved mothers they bought or hired.69 Furthermore, as owners or hirers they would not only be responsible for the well-being of the enslaved mother, they would also have to provide for any children who accompanied her. Therefore, indicating that an enslaved wet nurse would be hired or sold without her children eliminated later confusion and assured interested parties that these women would be able to perform their duties with minimal interference. Conversely, notifying readers that children would accompany the wet nurses who were offered for sale or hire helped all parties “avoid trouble” and reduced the likelihood of miscommunication between them.70

Information about an enslaved woman’s children was important to these market transactions for other reasons as well. Advertisers would routinely include information such as the birth order and ages of an enslaved wet nurse’s children; these statistics served as shorthand for individuals who sought enslaved wet nurses “with young milk” or a “fresh breast of milk.”71 An enslaved child’s birth order and age offered interested parties important details to help them determine whether the advertised laborer would suit their needs.

The testimony of formerly enslaved people and the language that individuals like Mrs. Dawson and Mrs. Palmer used when seeking to hire, sell, or purchase enslaved wet nurses reveal the ways in which a white woman’s decision to initiate and finalize such a transaction constituted an act of maternal violence. Maternal violence is generally defined as a case in which a mother commits a violent act against her own children. But here I offer another way of defining maternal violence that takes slavery into account. White mothers treated enslaved women’s bodies, their labor, and the products of their labor as goods, and in consequence were able to commit violence against these women, in their role as mothers, that slavery and the slave market made possible.72 In prioritizing their own infants’ nutritional needs over those of their wet nurses’ children, white mothers separated enslaved mothers from their children, often prevented enslaved women from forming maternal bonds with their infants and providing them with the nutrition they needed, and distanced them from the communities and kinship networks that were integral to their survival. The demands slave owners placed upon enslaved mothers as manual laborers and as wet nurses gave rise to circumstances that could result not only in psychological but also physical violence against these women and their children.73 And yet, white mothers like Ella Gertrude Thomas ignored or failed to acknowledge the effect their choices would have upon the enslaved women who nursed their white infants.

Thomas had experienced difficulty nursing because of an inadequate milk supply, and after her unsuccessful attempts to bottle-feed her babies, she chose to use at least four enslaved women to nurse her two infants. America and Georgianna nursed her son, Jefferson, and Nancy and Emmeline suckled her daughter, Cora Lou.74 Ella Thomas borrowed America and Emmeline from her father, who lived on a different plantation estate, thus separating them from their community. In her journal she did not reveal why she used two enslaved women to nurse her son. But several years later, when she used Nancy and Emmeline, she did indicate why one would not suffice. Nancy served as her daughter’s first wet nurse, but Thomas was prepared to install Emmeline as her replacement if Nancy’s milk did not agree with her infant’s palate. In her journal, Thomas never mentions how these enslaved women might have felt about her decision to use them as wet nurses for her children or the ways they might have supported each other through the experience. And Thomas seemed uninterested in the negative impact her choice had upon America, who had recently lost a child and would have been in mourning.75 What might enable a mother to so easily ignore or neglect to note another mother’s grief and pain?

In the eighteenth century, British men who bought female captives on the west coast of Africa claimed that these women did not have the same emotional attachments to their children that European women did.76 Such assumptions continued to shape how Anglo-Americans thought about enslaved women’s relationships with their children in North America and might help explain why millions of slave owners were so willing to sever parental and kinship bonds and why, when faced with enslaved people’s grief, trauma, and pain, they described it as something else. Ella Gertrude Thomas certainly subscribed to this idea when it came to people of African descent more generally. When the enslaved man who served as her driver informed her that he had been separated from his daughter and that his daughter had been separated from her children, Thomas remarked in her diary that they were fortunate because “the Negro is a cheerful being.”77 Such a view of African-descended people probably explains why Thomas failed to acknowledge the psychological distress her children’s wet nurses endured. In her estimation, these enslaved women were “cheerful beings”; they were not distressed at all.

White southerners developed a special terminology to describe enslaved people’s emotions, terms and phrases intended to render their pain, grief, trauma, and emotional loss invisible. The literary scholar Anne Anlin Cheng identifies a discourse common to both scholars and laypeople in discussions of race that views marginalized people’s expressions of grief as pathological, while simultaneously defining white people’s expressions of grief as healthy. Nineteenth-century white southerners employed their own version of this.78 When confronted with enslaved women’s emotional responses to losing or being separated from their children, white southerners construed their grief as “the sulks,” or even a form of madness—“vices,” flaws, or pathological conditions—that made such women less valuable and less desirable in the slave market.

An enslaved wet nurse with “the sulks” was one whom prospective buyers and hirers desperately sought to avoid. An advertisement in the City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser on June 16, 1792, for example, requested a “black wet nurse” who would “if possible be free from the sulks” and “of good disposition.” Yet their very desire to avoid confronting the mental anguish and psychic suffering of the enslaved mothers they hoped to acquire made the reality of that grief clear to anyone who read the advertisements. Scholars of slavery have elaborated upon the ways slave traders and slave owners compelled enslaved people to feign joy and contentment in the slave market precisely because their trauma and sorrow were palpable to buyers. White southerners also sought to disguise the maternal grief of enslaved women in their advertisements with claims that these mothers were “extremely fond of children” and possessed “cheerful” and “uncommon good” dispositions. The advertisers were, in essence, marketing a particular kind of maternal sentience along with enslaved women’s maternal labor.79

Enslaved mothers’ grief and white southerners’ attempts to render it invisible stand in stark contrast to the simultaneous “culture of mourning” that allowed whites to openly express their sorrow after the loss of loved ones. During the nineteenth century, white women were encouraged to mourn for the dead, and their “private expressions of grief helped usher in new conventions that enabled women to more fully express their acute sense of loss.” However, while “nineteenth-century [white] Americans were encouraged to openly mourn for the dead, especially for infants and young children,” white southerners brutally denied enslaved mothers and fathers the right to do the same. In the face of these denials, the enslaved mothers whom slave owners compelled to serve as wet nurses, particularly those who had recently lost a child or who were forced to separate from him or her, could not, or would not, hide their sorrow and grief, and such emotional displays were disturbingly obvious to owners and potential buyers. While from today’s perspective we might have assumed that the culture of mourning would inevitably lead white mothers to commiserate with enslaved women who lost their children or were separated from their infants, contemporary evidence makes it clear that women who employed wet nurses often chose to ignore enslaved women’s expressions of maternal grief.80

Whether they recognized it or not, white southern mothers were ultimately responsible for the ordeals that many enslaved wet nurses endured in and out of the slave market. These women decided when enslaved wet nurses would best serve them and their children, and only they knew the motives underlying these decisions. White mothers determined whether they could withstand the physical toll breastfeeding imposed upon them and whether they would be able to produce an adequate supply of milk to feed their newborns. Consequently, they were the ones who decided whether to borrow, hire, or buy an enslaved wet nurse, even if a man might finalize the transactions in the slave market. Some men did influence their wives’ decisions to charge other women with nursing their children.81 But the politics of respectability that shaped white southern culture and domestic relations ensured that few men would dare violate white women’s bodies in order to determine whether they were concocting reasons not to nurse, especially those of the elite and planter classes. Physicians, husbands, and other men had to take women at their word and allow them to make maternal decisions for themselves.82 White women separated enslaved mothers from their children and placed their own infants at the breasts of these women. They compelled enslaved women to suckle their white children shortly after these mothers had lost their own. They denied enslaved women the right to publicly express their grief. In short, they perpetrated acts of maternal violence against these enslaved mothers, and the slave market made this violence possible.