“THAT ’OMAN TOOK DELIGHT

IN SELLIN’ SLAVES”

In 1858, Elizabeth Childress decided that it was time to sell her only slave—a fifteen-year-old named Sally—and “convert her into money.” Childress was not much older than Sally when she made up her mind to initiate the transaction; she was still under twenty-one. But it was her prerogative to dispose of Sally if she pleased, for she had “acquired her of her own right and exercised all the rights and authority of a person of full age.” Rather than call upon her male relatives to broker the sale, Elizabeth Childress hired William Boyd, who was “a negro trader by occupation” and “kept a negro yard in the city of Nashville.” She probably settled upon Boyd because, like many of the most successful men in the slave trade, he routinely “published as a general agent to hire, purchase, and sell negroes for all persons who might avail themselves of his experience and honesty in the business.” Convinced that he was the right man for the task, Childress placed Sally in Boyd’s “negro yard” and waited for him to sell her for “the best price he could get.”1

A few days passed without any word, but Boyd soon informed Childress that he knew a man who would buy Sally for $1,000. Unfortunately for Childress, the sale fell through. A short time later, Childress walked into Boyd’s office and asked him about the prospects for Sally’s sale. This time he said he knew of someone who would be willing to buy Sally for $900. He assured her that this was all Sally “would command in the market,” and “that that was a very high price,” and he advised her to take it. “Trusting in his honesty and judgment as her agent,” Childress agreed to accept the lower price. Boyd immediately sat down at his desk and drew up Sally’s bill of sale. He identified William Whitworth and J. K. Taylor as Sally’s purchasers and handed Childress $890, the amount he owed her once he deducted his $10 commission.2

Elizabeth Childress left Boyd’s office that day with a sense of satisfaction, but her contentment was short-lived. She soon discovered that not long after Boyd sold Sally to Whitworth and Taylor, the two men sold the enslaved girl again—for $1,050. Moreover, she also suspected that one or both of the original “purchasers” were Boyd’s partners in his slave-trading firm. Boyd, Whitworth, and Taylor had bamboozled her. Not only did Boyd sell Sally for more than he originally said she was worth, he made a $150 profit. Childress believed that Boyd had “never exerted himself to sell” Sally, and the reason was that he had planned to “cheat and defraud” her from the outset. She was so staunchly certain about this that on March 1, 1859, she filed a lawsuit against the three men to get the money that she held to be her due.3

In a typical courtroom maneuver, Childress told the judge that Boyd, Whitworth, and Taylor had been able to perpetrate their allegedly fraudulent sale because she was “very young and unexperienced in business” and easily “imposed upon.” Contrary to her contention, however, her youth and inexperience had little to do with the profits Whitworth and Taylor made when they sold Sally. The circumstances that unfolded before, during, and after Sally’s sale, especially Boyd, Whitworth, and Taylor’s speculative practices, were systemic and fundamental dimensions of the domestic slave trade. The business ledgers slave traders maintained, and the trails of public, financial, and legal documents that followed every slave sale they initiated and finalized, routinely recorded similar transactions and profit margins. And Boyd, Whitworth, and Taylor’s response to Elizabeth’s allegations indicated as much.4

While Elizabeth Childress feigned youthful helplessness in court, Boyd argued that she had represented herself to be very much the lady when she came into his Nashville office. He told the court that she had never disclosed that she was under age and acted as though she had already reached her majority, when she would have the legal authority to dispose of Sally. Since she was a minor, he argued that the sale should be null and void because his title to Sally was invalid. Furthermore, Boyd denied Childress’s accusations that he had already sold Sally for the higher price before finalizing the sale with her. He also dismissed her charge that he had formed a partnership with Whitworth and Taylor and colluded with them to defraud her.5

Boyd’s answer to Childress’s charges revealed more than he might have intended, however. Just as she had suspected, Whitworth and Taylor were indeed “engaged in buying and selling negroes, and were in the habit of keeping their purchases at . . . Boyd’s establishment.” Boyd admitted that he did “sometimes become interested with his co-defendants in some of their purchases, as he did with other negro-dealers,” though he insisted that they maintained separate accounts. Whitworth and Taylor also claimed that when they purchased Sally they never expected to sell her for a profit in Nashville. They intended to sell her farther South, where they knew she would bring a higher purchase price. Before they could do so, a prospective buyer from Mississippi, James Lewellen, agreed to buy her. Thus, they argued, there was no collusion on the part of the three men. In fact, they charged Elizabeth Childress with deception and claimed that she knew that as a minor she did not possess the legal authority to sell Sally to them. They therefore asked the judge to declare the transaction null and void.6

In the end, the judge sided with Childress. He ruled that she was entitled to an additional $125. Thus, she received more than she had expected to get when she agreed to the sale. Despite being an underage female “unexperienced in business,” Elizabeth Childress was still able to initiate and partially execute a sale in the Nashville slave market and later win her case in the Davidson County Chancery Court. And when confronted by three slave traders in court, Childress left as the victor. Of course, she had help, but the individuals who aided her did not offer their services to shield her from the Nashville slave market or the commerce that occurred there. None of the parties involved in the sale or lawsuit mentioned her sex as a reason why Boyd, Whitworth, and Taylor had taken advantage of her. Nor did anyone claim that the sale should be invalid because she was a woman. In fact, everyone involved—from Childress’s friends, to the slave traders, to the judge—behaved as though it was perfectly natural for a woman to walk into a slave trader’s office and hire him to sell her slave. When Elizabeth Childress settled upon William Boyd as her agent, and when she brought Sally to his establishment, she was conducting business in the commercial center of the second-largest slave market in the state of Tennessee.7 None of these details deterred her.

Given what historians have said about white women and nineteenth-century southern slave markets, none of Elizabeth Childress’s actions should have been possible. One historian’s explanation for women’s exclusion from southern slave markets was that “by law and by custom white women had little business being” there. Another scholar made a similar point when he emphasized that “a slave trader or speculator was a man.” Yet in her examination of women and property in colonial South Carolina, the historian Cara Anzilotti found that white women “actively participated in the slave marketplace, buying and selling laborers, used them as a source of revenues by renting them out, and expected these slaves to further their relatives’ economic welfare.” She also contends that “many women managed the task of buying and selling slaves themselves.”8 This was also true of the nineteenth century.

Quantitative data analyses of the domestic slave trade have ignored female slave owners, be they single, married, or widowed. The economic historians Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman collected data on 5,009 transactions completed in the New Orleans slave market between 1804 and 1862. Their findings have since become one of the most widely used data sets in studies of American slavery, yet they offer no specific data about white women’s slave-market activities or buying and selling patterns. While Fogel and Engerman accounted for the sex, age, and color of the enslaved people who appeared in their data set, they did not collect similar information about the buyers and sellers of these individuals. Out of the forty-seven variables they gathered altogether, only two—initials and place of origin—pertained to buyers and sellers.9 Thus, we can use these data to analyze gendered elements of enslaved people’s experiences in the New Orleans slave market, but we cannot use them to determine how gender did or did not affect white southerners’ slave market activities.

The masculinized story of slavery’s nineteenth-century expansion and the rewards reaped from investing in that process through settlement on and cultivation of newly available lands serves to further marginalize white women and dismiss their economic contributions to slavery’s growth. Historians chronicle the ways that slavery, white voluntary migration, and the forcible removal and dispersal of indigenous and enslaved people and their labor transformed the nation’s political economy, as well as the global economy. But their narratives are built largely upon the stories of men. Women do appear in these histories, yet rarely does one find them among the ranks of “slavery’s entrepreneurs.” Instead, women often appear as mere tag-alongs.10

In some respects, the slave markets of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were different. In the wake of the Louisiana Purchase, the Adams-Onis Treaty, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the nation doubled in size during the first half of the nineteenth century. The market economy grew along with it, shifting from separate regional consumer markets to a national one. The slave trade changed from a system of exchange consisting primarily of the sale of captives from the Caribbean and the west coast of Africa to a domestic market involving the purchase and sale of enslaved people born in the United States. It became more regimented and more formalized and drew upon technological and fiscal innovations to maximize efficiency and profit.11 If women had access to the domestic marketplace in the colonial period, an era when the southern markets in slaves were disjointed, far from regional in scope, and rudimentary at best, then the developments that occurred during the nineteenth century probably brought more women into the slave market. Women responded enthusiastically to the development of a formalized, regimented, and regional slave marketplace, and they took advantage of the benefits that came with the transactions they initiated and finalized in those slave markets.

Travelers, slave traders, city officials, and enslaved people all attested to the presence of white women in nineteenth-century slave markets. White male and female sightseers visited slave markets and attended slave auctions during their excursions through the South, and they occasionally observed and wrote about the women they saw there. Although women rarely wrote about their exchanges with slave traders, the traders themselves routinely recorded their encounters with their female clientele who hoped to sell or buy the slaves they had in their possession, and they documented these women’s purchases and sales in their account books. Most southern states required slave sales to be formally recorded, and bills of slave sale, which functioned like modern-day receipts, reveal how frequently women bought and sold enslaved people. Clerks and notary publics in states like South Carolina and Louisiana recorded each and every slave sale and maintained meticulously detailed records of their business. Women’s names appear throughout these records as buyers and sellers of enslaved people. And in later interviews, formerly enslaved people repeatedly recalled the women who bought and sold them in the region’s slave markets.

Southern slave markets, it would seem, were tourist attractions for white travelers. The Swedish writer and social reformer Fredrika Bremer described the New Orleans slave market as “one of the great sights of ‘the gay city.’” For Bremer and travelers like her, these marketplaces were filled with striking scenes. For some, their encounters with white women in slave marketplaces and at slave auctions presented the most notable events they witnessed during their time in the South. Around 1859, Dr. John Theophilus Kramer attended a slave auction in the rotunda of the Saint Louis Hotel in the New Orleans French Quarter. Remarkably, at least to Kramer, he noticed “four ladies” who were “splendidly dressed in black silk and satin, and glittering with precious jewels” in attendance. These women were not standing discreetly on the outskirts of the festivities; they sat in close proximity to the platform upon which slaves would be sold. Kramer’s description of their attire suggests that they may have been members of the upper class. Equally notable, these four women came to the slave auction together, without male escorts.12

As the auctioneer called off the slaves for sale, recorded Kramer, he addressed both the men and the women in the room as potential bidders: “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “look here at this healthy child!” The four women did not participate in the auction proceedings, and Kramer offered a theory of why they did not. Although he deemed it plausible that the women already owned slaves and thus possessed the quintessential qualities that characterized slave owners as a group, their feminine sensibilities kept them from actually purchasing slaves themselves. Yet based on other historical evidence, it seems equally possible that they attended the auction to buy slaves with particular characteristics or skills, and the slaves exposed for sale did not meet their criteria, so they elected not to buy.13

The slave sale that Kramer attended and described does not conform to the kind of auction ordinarily associated with such transactions. Kramer describes an upscale, sanitized, and more palatable scene in striking contrast to the conventional image of a scantily clad slave up on an auction block in the center of a male audience of prospective buyers, usually in an auction house located in an obscure section of a city’s commercial district. The Saint Louis Hotel was one of the finest establishments in the city, offering accommodation to hundreds of guests, including military and political officials, and providing entertainment for city residents as well.14 The hotel’s rotunda was a breathtaking structure made of marble and encircled by columns and offices where auctioneers and others conducted their business. Perhaps this was a slave marketplace suitable for “ladies.”15 To be sure, the grandiose spectacle that unfolded in the Rotunda on the day Kramer attended was not the only kind of auction that took place there. But nonetheless, white women of all classes could be found among the observers and prospective buyers.

The author and clergyman Joseph Holt Ingraham also encountered a white woman in the Natchez, Mississippi, slave market he visited, but she was no spectator. She had gone to buy slaves, and that is exactly what she did. Just as Ingraham was preparing to leave, an elderly woman drove up in a “handsome carriage.” Accompanied by a young male, she entered the slave market and approached several enslaved females exposed for sale. She asked them questions in a “kind tone” before finally settling on an enslaved woman and her child. The young male who accompanied her appealed to her to purchase the enslaved woman’s husband as well, which she elected to do. And she left with the mother and child sitting beside her in the carriage and the husband in the coach box with her driver.16 Despite requiring the physical assistance of a companion, this elderly woman made a trip to the slave market to buy slaves on her own. Ingraham did not express the same surprise Kramer had about seeing a woman at the market, nor did he feel the need to rationalize her presence or her slave buying. He found her mode of transportation more remarkable than her actions.

Like Kramer and Ingraham, Fredrika Bremer was keenly interested in visiting slave auctions, markets, and yards during her forays into the South, and she wrote in detail about the women she met there. Accompanied by a male escort in New Orleans, Bremer walked “a short distance to the rail-road, on the other side of the river” and “passed through the slave market.” There she saw “forty or fifty young persons of both sexes . . . walking up and down before the house in expectation of purchasers. They were singing; they seemed cheerful and thoughtless. The young slaves who were here offered for sale were from twelve to twenty years of age. There was one little boy, however, who was only six: he belonged to no one there. He attached himself to the slave-keeper.”17 Bremer had come face to face with the landscape of the New Orleans slave market; it encompassed more than the slave yards, depots, warehouses, and auction houses—it also included the city streets. The scene she described was not one that other white women could avoid unless they stayed away from commercial centers altogether. In fact, it was commonplace.

Joseph Peterson was a free man of color who grew up on Canal Street in nineteenth-century New Orleans, and he would rise early in the morning before commerce commenced to “watch them parading the folks up and down.” The traders dressed the men in navy-blue suits and “stove-pipe hats,” while the women wore “pink dresses, white aprens, an’ red han’kerchefs on dey haids.” Traders would compel these enslaved men and women to walk the lengths of the promenade “two by two” so that they “would attract attention from the eyes of prospective buyers, to say the least.” These “parades,” Peterson remembered, were a “gran’ sight!”18

Fredrika Bremer was not content with simply visiting slave markets. She also traveled to the slave jails of Virginia, where enslaved people were held until their owners were ready to sell them, and to a slave pen in the District of Columbia.19 Much of the District’s slave trade occurred “in or near the taverns and small hotels, at the public market or the private jails and about the country markets” in the city; these were all places that women visited.20 During Bremer’s time in the District of Columbia, she spent many of her days in the Capitol listening to members of the Senate, and a male acquaintance, Dr. Hebbe, would frequently accompany her. Before going to the Capitol on July 21, 1850, he served as her escort to the slave market, and her “good hostess,” a married woman named Mrs. Johnson, also accompanied her. Mrs. Johnson “wished to have a negro boy as a servant,” and she hoped to purchase one. Although Dr. Hebbe escorted Bremer and Mrs. Johnson, he was not the person who bargained with the slave keeper: Mrs. Johnson took care of this business herself. She went to the slave pen with a precise idea of the kind of slave she wanted to buy, and she knew how much she wanted to pay for him. But this particular slave pen was a holding station in which enslaved children were “fattened” and prepared for sale before being shipped to slave markets in the lower South, so the slave keeper was unable to accommodate her.21

The women of Charleston could also visit their city’s slave traders, or they could attend public slave auctions. The largest of these routinely occurred at ten o’clock in the morning, right “in front or just north” of the customhouse. The building also housed the post office and was near “City-Hall, the Courier and the Mercury [newspaper] buildings,” and “nearly all the churches and banks,” as well as the “offices of many lawyers, factors, brokers, commission merchants,” and other commercial agents. The auctions were so large that the city passed an ordinance in 1856 forbidding such commerce because “the crowd often overflowed into the East Bay street and obstructed traffic” and “was sure to attract the attention and excite the condemnation of Northern and foreign travelers.”22

This might have been where Harriet Martineau, a British sociologist, feminist, and traveler, encountered a public slave auction. Just as she arrived, the auctioneer was exposing “a woman, with two children, one at the breast, and another holding her apron” for sale. She surmised that the woman’s “agony of shame and dread would have silenced the tongue of every spectator; but this was not so.” According to Martineau “a lady chose at that moment to turn to me and say, with a cheerful air of complacency, ‘You know my theory, that one race must be subservient to the other. I do not care which; and if the blacks should ever have the upper hand, I should not mind standing on that table, and being sold with two of my children.’”23 The woman was not repulsed or disgusted at the sight of an enslaved mother being sold with her children, even though she was a mother herself. Her gender and motherhood did nothing to compel her to sympathize with the enslaved woman’s plight. In fact, she seemed relatively comfortable with the idea of all human beings being sold to the highest bidder.24

It is critical to acknowledge that slave trading was not sequestered in urban vice districts because it was not considered a vice.25 It was part of the fabric of southern communities and the region’s economy. Slave traders often clustered in particular segments of commercial districts, and they marked their businesses to make them easier to find. Even a woman like the diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, who belonged to a prominent South Carolinian slave-owning family and was married to a high-ranking political figure, would confront the peculiar institution’s ugly underbelly during occasional strolls into town.26

As Ann Maria Davison and her acquaintance Mrs. Benton solicited New Orleans residents for donations to support the “Bible Cause,” they “came in contact with four negro Traders Yards”:

We stopped at the door of one of them not knowing its character. One of the most pleasant smiles sat upon the face of the odious trafficker as he advanced to the door and invited us in. . . . [T]rue to my earnest desire to see all I could of the traffick I said let us go in. The trader looked all delight! Here ladies, said he, is as fine a lot of young Negroes as you will find any where, and turning round to them who were all seated on benches round the large room with their newly purchased suit for the occasion—he gave this word of command in a very peremtory manner by saying Form the line. In an instant they all sprang to their feet making two long rows not one seemingly over twenty years old and truly were they a likely looking set of young men and women.27

As this encounter shows, slave traders and dealers did not consider female purchasers to be anomalous. Moreover, when white women entered slave traders’ offices and slave dealers’ establishments, the enslaved people waiting to be bought acknowledged them as property owners with the money, power, and authority to buy them.

Davison and Benton’s inability to recognize a slave trader’s establishment could be attributed to their lack of familiarity with the business, but it is far more likely that it was because the businesses of slave traders and other kinds of merchants were indistinguishable. As Fredrika Bremer observed, the “great slave-market” consisted of “several houses situated in a particular part of the city,” which visitors would probably find unremarkable until they encountered “the groups of colored men and women, of all shades between black and light yellow, which stand or sit unemployed at the doors.” Speaking directly against the notion that women avoided the sexual aspects of the slave market, Bremer remarked upon the enslaved men with “really athletic figures, . . . good countenances and remarkably good foreheads, broad and high.” There was “one negro in particular” who captured her attention. He was valued at “two thousand dollars.” Although Bremer was in the slave market to observe, she “took a great fancy” to this enslaved man, and “said aloud that she ‘liked that boy’” and was sure that she and he “should be good friends.” She was playing the role of slave buyer, but the enslaved man’s response to her chatter revealed that he took her seriously.28

Women could examine enslaved people’s bodies, take notice of their features, talk to them, and express a desire to buy them, all in public view. If what they saw piqued their interest, they could enter the trader’s establishment and be assured that the proprietor would cater to their needs. Such evidence further refutes the argument that white southern women were repulsed by or alienated from slave markets and ignorant of the details of slave transactions.

Residential and business directories and censuses of merchants show that hundreds of women conducted business in the same places where slave traders plied their trade. They also reveal that the layout of commercial districts in nineteenth-century southern cities made it difficult for white women to avoid slave marketplaces or evade the business and economic community that flourished there. New Orleans city and business directories show that women worked on the same blocks as slave traders, and some of their businesses were only a few doors apart. A Madame Harriet, for example, established her oyster restaurant on the corner of Gravier and Philippa Streets, with the slave trader C. F. Hatcher located nearby on Gravier between Philippa and Baronne. Mrs. Mary Sweneua (or Brzarenne) operated a fancy retail shop on Baronne, Gravier, and Common Streets. The slave dealer Thomas Foster worked at 157 Common Street between Baronne and Carondelet. Foster’s fellow slave dealers Frisby and Lamarque’s establishment was located at 156 Common Street also between Baronne and Carondelet.29 The directories also show that female merchants outnumbered individuals who identified themselves as slave traders in the commercial center of the city, thereby suggesting that these men were locating their businesses in proximity to the female merchants, not the other way around. For example, Cohen’s New Orleans and Lafayette City Directory lists 427 female merchants or businesswomen operating in the city in 1849. This number jumps to 463 if the women who worked as teachers and principals and who ran schools and seminaries are included.30 Yet only 20 male slave traders and dealers appear among them. Of course, many people involved in the slave trade did not call themselves traders, dealers, or auctioneers. They often identified themselves as “planters,” “commission merchants,” “factors,” and “agents” because they often sold other commodities or conducted other types of business transactions in addition to slave sales.

It is important to recognize, too, that the commercial districts of cities like New Orleans were bustling with white women. The 1854 Census of Merchants offers evidence of women’s commercial activity in the city. There were 330 licensed female merchants operating in the first, second, and third districts of the city. This number only hints at the actual number of working women in the area because the census only tracked individuals who were employed in professions that required licensure. Many of the most common occupations for women, such as seamstress work, laundering, baking, and confectionary work did not require a license, and the women who were employed in these kinds of labor were not counted.31

Female merchants and entrepreneurs who worked within public marketplaces provided the kinds of goods and services that could prove useful to slave traders. Their proximity to the slave trade’s primary arbiters and the demand for what they had to offer made it feasible for slave traders and dealers to buy white women’s goods and services, even if those “services” consisted of enslaved labor. The woman who owned Susan Boggs, for example, hired her out to a slave trader to work “in the trader’s jail.” Boggs’s mistress was thus indirectly benefiting from the slave trade. The trader made a living buying and selling human beings, and Boggs’s labor was directly tied to business that occurred in the “trader’s jail.” By extension, the wages Boggs gave her mistress and the benefit her mistress derived from those wages were made possible because of the sale of human beings.32

Single, married, and widowed women appear frequently in slave traders’ correspondence and in legal documents that recorded the purchase and sale of slaves. The slave trader A. J. McElveen, for example, contracted with several women who wanted him to buy or sell slaves on their behalf, and he wrote letters to his partner Ziba Oakes about them. On August 10, 1853, McElveen notified Oakes that he had sent him a slave he purchased from a woman named Mrs. Pedrow while he was in Sumterville, South Carolina.33 Nineteen days later, he wrote Oakes again, from the Darlington, South Carolina, courthouse, and in a postscript informed Oakes that he “saw the lady Mrs. Blackwell who wishes to Sell 4 or 5 negros. She has promised to waite until I Return from charleston before She sells.”34 Two years later, McElveen wrote to Oakes seeking advice on how to handle a matter arising from a sale involving his purchase of two enslaved men who belonged to a woman named Miss Fleming. In his January 13, 1855, letter, he told Oakes, “I have just Received a note from Miss Fleming, the lady I bought George & lefegett from. . . . She will take boath the boys as I could not Settle with them by Returning one.” Three days later, he asked Oakes for assistance again: “Will you advise me the course to persue in this Case[?] Miss Fleming is not willing to take one boy without the other therefore I am at a lost to Settle the matter as She has my note and will not Give it up.”35 Although white women do not appear regularly in McElveen’s letters, the instances in which they do reveal that they dealt with him on numerous occasions, entrusted him with their economic investments, bought slaves from him, and sold them to him as well. More important, McElveen never mentioned the involvement of male kin or proxies; nor did he express reservations about dealing directly with women or imply that these women had concerns about dealing with him. In fact, his letters show that his female clients were in control of the sales and purchases, and at least one of them exerted enough pressure on him that he felt compelled to write Oakes more than once about how to resolve the situation.

Bills of sale also reveal that slave traders throughout the South bought slaves from and sold slaves to women on a regular basis. On December 16, 1845, Harriet A. Heath purchased a twenty-three-year-old enslaved woman named Jane from Ziba Oakes, and on July 8, 1846, she came back to him for another purchase. This time she bought a twenty-eight-year-old enslaved woman named Dianna who was “warranted sound and healthy.”36 Elihu Creswell bought a slave from Marie Carraby; Miss Eleanor Hainline bought a slave from George Ann Botts, John Hagan sold a slave to Mrs. Mathilda Mascey; Margaret Flood sold a slave to John Rucker White; and William Talbott sold a slave to Mrs. Louise Marie Eugenie Bailly Blachard.37 It is not clear whether these women went to their local slave market to buy or sell their slaves, but they certainly negotiated directly with slave traders and dealers and finalized the transactions with them.

Slave traders’ account books and ledgers offer further evidence of transactions with women. The slave-trading partners Tyre Glen and Isaac Jarratt sold enslaved people to Clarissa H. Mabson, Elizabeth Nobles, and Nancy Capehart and bought one from Sally M. Craw. Between 1849 and 1859, John White bought and sold enslaved people to women on at least forty-eight occasions, and he recorded seven additional sales without dates. Several of White’s transactions are worthy of note. In 1849, Madame Mollere bought five enslaved people—three women, one man, and one of unspecified sex—from White. She purchased another enslaved woman the following year. Three other women, Mrs. A. Cross, Mrs. Newman, and Mademoiselle Bersije, also bought enslaved women from White that year. While White’s female customers overwhelmingly bought enslaved girls and women from him, some, especially those engaged in sugarcane cultivation and processing, spent their money on enslaved men. In September 1852, Madame Burke of Lafourche Parish bought two enslaved young men, a twenty-year-old named Jack Barnet and a seventeen-year-old named Wiley Shields, from White for twelve hundred dollars each. He made a thousand-dollar profit. All together, at least thirty-five women bought enslaved people from him.38

White women were not anomalies at local slave auctions, either, and no group could testify more powerfully to white women’s presence at and involvement in slave auctions than the enslaved people who were there. Formerly enslaved people remembered these women as astute, sophisticated, and calculating slave-market consumers. One formerly enslaved person remembered several white women at the public sale of a mixed-race woman; when the woman was placed on the auction block, the white women in the crowd exclaimed, “I don’t want that mulatto bitch here.” It was common for white men to purchase mixed-race women as part of the “fancy trade,” a sector of the slave trade that catered almost exclusively to white men who sought to purchase sexual slaves. The white women who objected to the sale of this mixed-race enslaved woman probably knew this.39

The women present at this auction seemed to be spectators rather than buyers, but enslaved people also described women who actively participated in the bidding at other auctions. When B. E. Rogers asked his formerly enslaved father whether he had ever seen a slave auction, he replied, “Yes, I saw one at Raleigh once. About half a dozen Negroes being sold, mostly to women.”40 Liza Larkin bought Ank Bishop’s mother at a slave auction in Coke’s Chapel, and in acquiring an enslaved woman of childbearing age who could perform household tasks, she made an economically sound choice. Bishop’s mother cooked, washed, and milked Larkin’s cows. She also gave birth to Ank and five other children, and with each infant, Larkin watched her initial investment increase.41

Occasionally formerly enslaved people also spoke of their female owners’ unique slave-market selection processes and buying habits. Ike Thomas’s owners sold his parents away from him when he was a child, but his mistress kept him so she could train him to be a carriage boy. As Ike spoke of his life on the Thomas plantation, he reflected upon his mistress’s distinct way of determining which slave boys would be suitable for purchase. She paid particular attention to the way they wore their hats. If the enslaved boys set their hats “on the back of their heads,” she believed that they would grow up to be “‘high-minded,’ but if they pulled them over their eyes, they’d grow up to be ‘sneaky and steal.’”42 When Rose Russell’s mistress decided to sell her, she asked Russell which of her parents she loved the most. Russell contemplated the question for a few moments before saying she felt the most love for her father. The mistress sold Russell with her father and separated the young girl from her mother.43

Sometimes white women saw financial opportunities in the very situations that white men thought burdensome. Some men considered enslaved children not worth the costs associated with rearing them to working age. Thomas Jefferson claimed that “the estimated value of the new-born infant [was] so low, (say twelve dollars and fifty cents,) that it [the infant] would probably be yielded by the owner gratis.” Jefferson hatched a plan to deal with such nuisances, and at least a few slave owners considered it a good one. In a letter to Jared Sparks dated February 4, 1824, Jefferson proposed emancipating the infants of enslaved women, compelling their unfree mothers to care for them until they were able to work, and then deporting them. Shortly after Nat Turner led his slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia, a group of concerned male citizens put forth a petition to implement Jefferson’s plan.44 That never came to pass, but some male slave owners and traders showed that they agreed with Jefferson’s low valuations of enslaved infants when they gave enslaved infants and children away to white women. H. B. Holloway recalled that at some slave auctions, “a woman would have a child in her arms. A man would buy the mother and wouldn’t want the child. And then sometimes a woman would holler out: ‘Don’t sell that pickaninny . . . I want that little pickaninny.’ And the mother would go one way and the child would go another.”45 Infants could be especially troublesome to itinerant slave traders transporting enslaved people to the Deep South. While William Wells Brown was enslaved, he worked for a slave trader who became so annoyed by an infant’s incessant crying that when they stopped to rest at an acquaintance’s house, he gave the enslaved newborn to the man’s wife as a present. She, perhaps more market-savvy than the trader, thanked him.46

Children cost far less than enslaved adolescents or adults, and if a slave owner was willing to pay the lower purchase price and invest in the care of the child until he or she was old enough to work, the owner could see his or her investment grow exponentially over the enslaved child’s lifetime, especially if the child was female. Some white women chose to acquire enslaved infants and children for free or at rock-bottom prices, a decision that would eventually pay off handsomely.

Besides benefiting from their personal transactions in slave markets, women also served as intermediaries, attorneys-in-fact, and agents for other women and men, including slave traders, who wanted to buy or sell slaves.47 In the latter months of 1852, after the slave owners Elias and Mary Gumaer moved to Wisconsin, they hired Ann Young to sell their slave Letty and her son William in the District of Columbia. They stipulated that she not sell the two to slave traders or to any buyer who would remove them from their own community. Young kept her end of the bargain, going so far as to sell them for a much lower price than they were worth and rejecting higher offers from several local slave traders. But Peter Hevener, the man who bought the Gumaers’ slaves, did not bind himself to the same terms. The Gumaers petitioned the court to prevent him from selling Letty and William out of state, and their case elucidates Ann Young’s extraordinary slave-market activities, which might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

The Gumaers’ petition suggests that they considered Young to be a competent, astute, and trustworthy arbiter of the slave market. The slave traders and prospective buyers who approached her about buying Letty and her child probably saw her in this light as well. She possessed important knowledge about the slave-market economy, and what she knew allowed her to negotiate with a host of prospective buyers. Perhaps the couple entrusted Young with the transaction because she was a family member or because Letty and William were in her possession already and the Gumaers saw her as the most logical person to sell them. But whatever the reason, if they had not believed that Ann Young could sell Letty and William while simultaneously abiding by their wishes and obtaining the best possible price, they had other options. Everything Young did as the Gumaers’ agent defined her as a slave dealer. They may not have wanted her to sell Letty and William to slave traders, but in appointing her to sell them at all, the Gumaers essentially authorized Young to assume that title.48

The intricacies of this sale make it abundantly clear that women like Ann Young did engage in complex slave-market transactions, and this was the case even when spouses or male proxies were involved. While some married women entrusted their husbands with conducting portions of their business in the slave market, they often handled other aspects of these transactions themselves. Ruth Williams is an example. Her mother bequeathed an enslaved woman and her children to Williams and her sister, stipulating that the property should be for the women’s “sole and exclusive use and benefit” and should not be seized to satisfy their husbands’ debts. The sisters decided that Ruth would get the male child of the enslaved woman, “he then being about twelve or fourteen years of age,” and her sister would take the enslaved woman and any remaining children she might have. Upon securing the enslaved boy, however, Ruth discovered that he was “a stubborn, bad boy” and “she found it very hard to control him.” She feared “that when he grew up to be a man . . . she would not be able to keep him in proper subjection.” Since Ruth was “in very feeble health, and standing greatly in need of a woman to assist her in her domestic . . . business of her house,” she “instructed and requested” that her husband “dispose of” the enslaved boy for her, “either by exchanging him for a woman, or by selling him and purchasing for her a woman with the proceeds.” Furthermore, she specifically told her husband to do one of two things: “exchange him for a woman owned by one of her acquaintances or . . . sell him for not less than six hundred dollars cash.” If he could not do either, he was “to return her the boy.” Her husband returned without the boy and placed $408 in Ruth’s hand, claiming that the funds were only “part of the proceeds” from the sale and she would soon receive the rest. On January 1, 1853, she “heard that one Zachariah R. T. McGuire had in his possession a negro woman that he wished to sell.” Despite her “very feeble health,” Ruth Williams visited McGuire, “examined said woman . . . in person . . . and after seeing her she contracted with . . . McGuire for the said woman,” named Nancy. The contract stipulated that Williams would take possession of Nancy and assess her disposition and the quality of her work for a trial period, and if she was “pleased after trying her,” she would purchase her “at the price . . . of two hundred and fifty dollars.” Williams found Nancy to be a suitable servant, and she decided to buy her. She asked her husband “to go and complete the purchase . . . and to have the bill of sale executed to her, as her separate property.” Ruth Williams allegedly needed this enslaved woman because of physical ailments, not simply so she could escape domestic labor or ascend to ladyhood. Furthermore, Ruth Williams underscored the fact that “her . . . husband completed the trade” on her behalf and that he did so with money he “obtained by and through her, and not from [his] means or money.”49

Even though men conducted some aspect of women’s business in slave markets, women did venture into these markets or attend slave auctions themselves. When Jane Buie was seventeen years old, she decided to purchase an enslaved woman and her children. She had enough money, but “she was young and timid and did not like to come into the crowd.” So she asked her father, Malcolm, to accompany her to the auction and bid upon the enslaved mother and child as her agent. Before the sale began, Malcolm pulled the commissioner of the auction aside and informed him that his daughter wished to bid. However, because of her apprehension about the crowd, he was going to bid on her behalf. The commissioner assented to this arrangement. Once Malcolm Buie secured the commissioner’s assent, he then “made known” to the crowd of prospective buyers that he was bidding “not for himself” but for his daughter. Malcolm was the highest bidder, and he later delivered the bill of sale to Jane and accompanied her to Cumberland, North Carolina, where she retrieved her “property.”50

Jane’s decision to ask her father to bid was probably based on her lack of experience, and perhaps the anxiety of trying to bid in a crowd of individuals who might have participated more routinely in the frantic bidding that characterized these auctions. Since she trusted her father to handle the transaction adeptly, she did not have to attend the auction in person. But her decision to do so suggests that she might have wanted to observe the bidding process so as to gain a deeper understanding of how to bid successfully in the future. It is also important to recognize that her father did not use this as an opportunity to affirm his masculinity or role as paternal protector; rather, he let the auctioneer and the crowd know that his daughter was present and he was merely acting on her behalf.

It was common, however, for women to initiate and finalize transactions in the marketplace themselves. When a formerly enslaved woman named Sarah was “jus’ de age when gals begin bringin’ good money in de market,” a slave trader stole her from her mother. After trying unsuccessfully to sell her in several slave markets in different states, the trader decided to try again in New Orleans. Once they arrived in the city, the trader placed Sarah in a “trader-house,” where she remained for several days. When it was time for the auction to take place, he prepared Sarah for sale by cleaning her up and giving her a new dress to wear. Later, Sarah described what happened next. The trader placed her on the auction block and Sarah began to see “de white folks pass by.” Soon, she noticed a “white lady stop an’ look” at her. After giving Sarah a thorough once over, the woman approached the slave trader and spoke to him for a while. Then she mingled with members of the growing crowd and suddenly exclaimed, “I think dat nigger gal was stole!” The woman approached Sarah again and began to ask her a series of questions: “‘Whar yo’ live at, gal?’ de lady ask.” Sarah replied, “My home in South Car’lina, Ma’am.” “Don’ you want ter come live wid me?” the woman asked. Sarah responded, “Yas’um.” Satisfied, the woman returned to the crowd of prospective buyers and waited for the bidding to commence. As the auctioneer called off the bids, the woman staked her claim to Sarah and called out her price: “I’ll take dat little nigger,” she said. “Bid hundred an’ fifty dollars!” She won. “Sold!” the auctioneer said. “An’ she pay him.”51

Sarah’s female owner attended a slave auction, saw an enslaved girl exposed for sale, questioned her, decided to buy her, and successfully bid for her. She was clearly familiar with the litany of questions prospective buyers should ask the enslaved person they hoped to purchase, and she asked them to find out what she wanted to know.52 She also displayed a sophisticated knowledge about the intricacies of slave commerce. Something suggested to her that Sarah was in an unfamiliar place. While such a scenario was not unusual, given the stream of enslaved people whom slave traders purchased in the Upper South and sold in the Lower and Deep South, Sarah’s new owner recognized a different kind of displacement. Perhaps Sarah’s youth implied that she had been sold away from her mother, something that was strictly prohibited under Louisiana acts passed in 1806 and again on January 31, 1839.53 These acts stipulated that individuals must sell enslaved children who were younger than ten with their mothers, unless they were orphans. The man who captured and later sold Sarah might have been taking advantage of the “orphan loophole” by stealing her, and others, and selling them in distant slave markets where owners could not find them and potential buyers could not trace their origins. Sarah’s new owner might not have cared whether Sarah was in fact stolen. If she really had been concerned about Sarah being kidnapped, she could have refrained from bidding on her, as others sometimes did, or tried to find Sarah’s rightful owner.54 Instead, she used allegations of unlawful sale as a means of decreasing the number of people willing to bid, which kept the bidding price low. Confronting the slave trader and canvassing the crowd of prospective buyers to spread news of her suspicions, Sarah’s owner exhibited her slave-market savvy and comfort within the slave-trading community.

Beyond street-side sales of this kind, women also attended auctions in places like Bank’s Arcade, a New Orleans venue that was “situated in the very center of business,” and was well known for its sales of enslaved people, for “mass meetings of . . . various political parties,” and for being a “great resort for merchants and others.”55 On June 10, 1843, for example, Bedilia Gaynor Kellar attended a public auction there. That particular day, Richard Richardson called off the bids. Richardson was the business partner of Joseph A. Beard, a man who was considered “New Orleans’ most prominent auctioneer” and “the largest slave-seller in New Orleans during the ’forties and ’fifties.”56 Upon seeing an enslaved woman named Aimé standing on the auction block, Kellar decided to place a bid. She continued to raise her offer until the auction closed and she was the “last and highest bidder.” She took Aimé home for $530.57

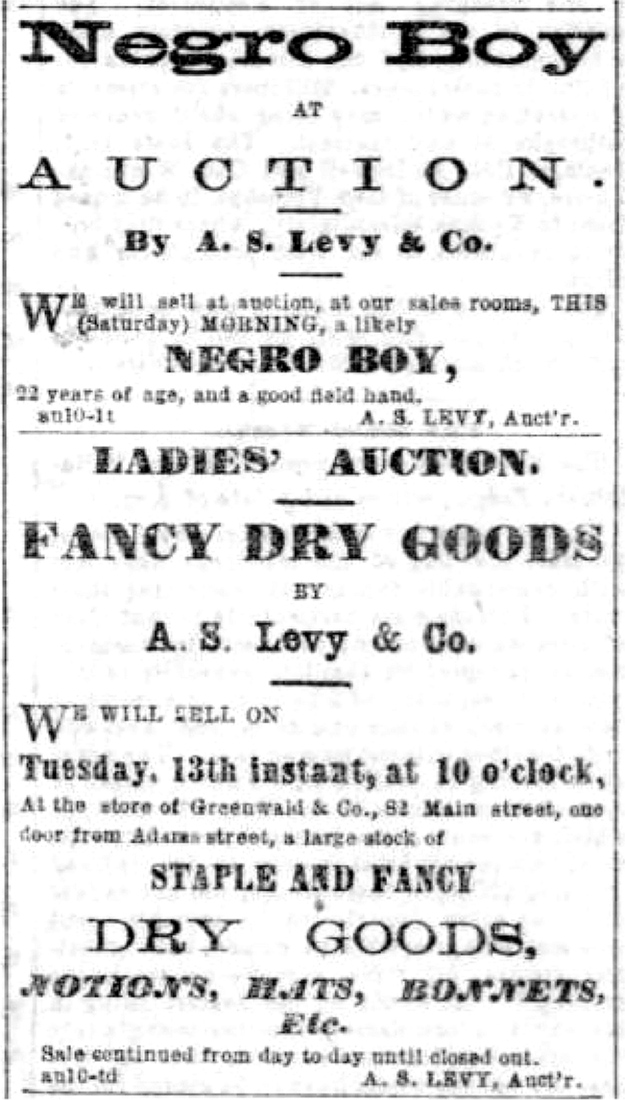

Women sold and bought enslaved people, and just about everything else, from men like Richardson and Beard. Auctioneers advertised sales for slaves as well as for bonnets, fabrics, lace, women’s dresses, and ladies’ shoes. If she were in the market for one, a woman could also buy houses, lots, and plantations. Individuals in cities and towns throughout the South regularly held auctions just for women, at which they could bid upon a variety of items such as “bedsteads, bureaus, chairs, carpets, [and] mattresses,” as well as “a splendid assortment of rich dress goods and trimmings, elegant silk . . . cloaks . . . wool blankets, counterpanes, quilts,” and “housekeeping articles.” G. W. Hanna called upon “all the ladies” to attend auctions he held “every morning and evening” just for them. E. Barinds and Company also held “ladies’ auctions . . . every Tuesday and Friday from 2 to 5 o’clock during the month of December” in 1857.58 “Ladies’ auctions” took place in cities like Charleston, New Orleans, Iberville and Shreveport, Louisiana, Nashville, Memphis, Baltimore, Richmond, Hannibal and Glasgow, Missouri, and Raleigh, Fayetteville, and New Bern, North Carolina. These auctions were well attended; sometimes crowds of a hundred or more women would pack themselves into the auction rooms. It became so crowded at one of these venues that women had to stand on chairs to view the items put up for bid. The same men who held ladies’ auctions also served as auctioneers “for the sale of real estate, slaves, successions and out-door business generally.”59 They often announced their ladies’ auctions and the sales of enslaved people in newspaper advertisements that appeared side by side. Rapelye, Bennett, and Company, for example, promoted the auction of a “mulatto wench, with her child” as well as her eight-year-old brother, directly above a notice expressing their intention of having a “ladies’ auction” the next day. Similarly, A. S. Levy advertised the sale of a “negro boy,” who happened to be twenty-two years of age, directly above his ad for a Ladies’ Auction he planned to hold the following Monday.60

“Negro Boy at Auction by A. S. Levy & Co.” and “Ladies’ Auction. Fancy Dry Goods by A. S. Levy & Co.,” Memphis Daily Appeal, August 10, 1861 (Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress)

Ladies’ auctions taught women all they needed to know about bidding at auctions where enslaved people were the “goods” being sold. The auctioneers who orchestrated these events probably used the same chants they employed to auction off enslaved people, and allowed winning bidders to pay for their items with cash or on credit if the purchase prices exceeded a certain amount.61 Although auctioneers did not sell enslaved people at ladies’ auctions, their effective and voracious advertising ensured that women would know where to find such auctions, if they did want to buy them.

When women sold slaves in public markets, they sometimes did so because of familial responsibilities.62 Yet even under the pretext of resolving family business, some women sold enslaved people for more selfish reasons. Charity A. Ramsey was acting as her husband’s estate administrator when on “the first Tuesday in June 1857,” she organized a sale in Campbell County, Georgia, at which she sold a seven-year-old enslaved girl named Martha to Zadock Blalock. Blalock soon discovered that Martha was afflicted with a “running off of the bowels,” a malady that local residents attributed to her tendency to eat dirt. At least two physicians claimed that she suffered from typhoid “numonia” and typhoid fever. Whatever her affliction, Martha eventually died of it. Blalock accused Ramsey of selling him a sickly slave who she knew was ill and falsely warranting her as healthy and sound.63 He was right. Ramsey had told two of her female neighbors that her decision to sell Martha and other slaves had nothing to do with repaying her husband’s debts. She planned to sell them because they were sick and she feared “they might die and she would loose them.”64 Ramsey decided to sell these enslaved people because she did not want to lose their value.

Women also sold enslaved people because they were too old, because they were male instead of female, or because they found their temperaments disagreeable. Women like George White’s mistress sold enslaved people so they could buy dresses with the proceeds. White recalled that his mistress “was a dressy woman,” and her penchant for the latest fashion often led her to the slave market. He said that whenever “she wanted a dress, she would sell a slave.” The desires that could be fulfilled through the slave market seemingly had no end, and whether a woman wanted servants who were younger, of a different sex, or better behaved—or even a new dress—the slave market helped satisfy her needs.65

Frequently, though, women unburdened themselves of laborers they deemed unworthy of their continued investment, and in most cases, they did not care about the lasting consequences such decisions had upon enslaved people’s lives.66 Sometimes, in fact, such traumas were part of their decisions. Leah Woods decided to sell her slave precisely because she knew that doing so would remove him from all he knew and loved. Woods considered her slave Buck, who was “young and very likely,” and was “at that time worth twelve or fifteen hundred dollars,” so “insolent and highly provoking . . . [that] she determined as a punishment to send him out of the state,” “far off from his kindred and those with whom he was familiar.”67

White women sometimes decided to sell enslaved people away from their loved ones and communities for darker reasons. Eliva Boles’s first mistress sold her because Boles’s master was her father.68 Sarah Hill and Margarette J. Mason wanted to sell enslaved men because they were “too white to keep.” Both men were so light in color that they could successfully pass as white. Hill and Mason were concerned that the men would run away and they would incur significant financial losses. Mason was able to finalize the sale of her slave in time, but Hill was not so lucky. Once Edmund, the mixed-race, nineteen-year-old enslaved man she hoped to sell in the New Orleans slave market, discovered her plan, he made his escape. Months later, after placing multiple runaway advertisements, she still had not found him.69

Another formerly enslaved woman spoke of being sold twice. Her first mistress sent her to a slave trader’s office to be sold because she had violently resisted the sexual advances of her mistress’s son. Her second mistress demanded that she be sold because she was a “half white nigger” whose presence disturbed the mistress so much that she gave her husband an ultimatum: if he “didn’t get rid of [her] pretty quick she was goin’ to leave.” When a month passed and he still had not sold the enslaved woman, his wife left, just as she promised. The husband took the enslaved woman back to the same slave trader he had bought her from. These white women did not sell enslaved people out of necessity; they got rid of them because of shame, jealousy, and anger.70

On rare occasions, women sold slaves because it was a lucrative business. At the close of the American Revolution, Ann Robertson engaged in activities that could undoubtedly be characterized as slave trading. She attended slave auctions, sought out sickly slaves, and purchased them. She nursed them back to health and then sold them for a profit. Robertson recognized that such business strategies involved uncertainties that could prove ruinous. Even her husband, John, tried to warn her about her risky bidding behavior, but she “repelled his interference and said the money was her own [and] she would do as she pleased with it.” He replied that this “was no reason she should ruin herself.”71 But Ann was willing to take her chances despite her husband’s warning and the risks. She knew that sick slaves cost less than healthy ones, and she understood that there was no guarantee that they would recover. But she also knew that if their health did improve, she could sell them for much more than she paid for them.72

The kind of speculation that Ann Robertson engaged in required a sophisticated understanding of the vagaries of the slave market, a willingness to gamble on the physical uncertainties inherent in the bodies she exposed for sale, and an acceptance on the part of prospective buyers that they could trust the person presenting these bodies to them for purchase. Her gambles paid off. Through her slave trading and other commercial endeavors, Robertson amassed considerable wealth and a substantial amount of property in her own name. At the time of her death, she possessed an estate worth more than fifteen hundred pounds. Twenty-seven enslaved men, women, and children were listed among her most valuable possessions.73

Some white women partnered with others to trade in slaves for profit. One such woman was a widow named Mathilda Bushy. Because she did not keep a diary or write letters, much of her life remains cloaked in silence, but notarial and court records lay bare her extensive investments in the New Orleans slave market and trade as well as her relationship to Bernard Kendig, one of the wealthiest and most infamous slave traders in the city.74 When Bushy decided to sell seven of her slaves, she hired Kendig to handle the sale and it became one of the many he transacted for her during his lucrative career.75 For two years, Kendig acted as Bushy’s agent and attorney-in-fact, and he bought and sold numerous slaves for her in this capacity. One historian has claimed that Bushy was merely an underwriter for Kendig’s trade and that the slaves he bought and sold may not have been hers. Court testimony from an 1858 case filed against Kendig would seem to support this conclusion.76 N. Folger and J. Folger sued Kendig for payment of a debt he owed them. Kendig refused to pay because he claimed that he was insolvent and could not jeopardize his livelihood and his family’s well-being. The Folgers contested his claim, asserting that he possessed considerable wealth. Their legal counsel called upon Kendig’s former business partner and fellow slave trader James W. Boazman to support their assertions. Boazman testified that Kendig conducted business in Mathilda Bushy’s name in order to avoid paying his creditors. He also claimed that she had nothing to do with their slave-trading business because he himself had never seen her and did not personally know her.77

Boazman, however, did not tell the court the whole story. The Folgers’ 1858 case, and other suits that preceded it, reveal that Bushy and Kendig were more than business associates. Moreover, these legal records show that she was more intricately involved in Kendig and Boazman’s slave-dealing business than the latter wanted the court to believe. She was, in fact, Kendig’s aunt, and the United States census identifies her as one of the individuals residing in his household in both 1850 and 1860. In the 1856 case that William H. Nixon filed against Boazman and Bushy for selling him a sickly slave, Kendig was compelled to testify. His testimony in this case makes it clear that he was actually Bushy’s employee. When Nixon’s counsel asked Kendig whether he had a personal stake in the outcome of the case, he claimed that he had no interest in the final judgment and qualified his financial disinterest by explaining his business relationship with Bushy.78

According to Kendig, Bushy gave him money to buy and sell slaves on her behalf. He would then retain a portion of the profits and give her the rest. Under cross-examination, Kendig stated that his compensation came from the commission he earned on each sale. The suit also contradicts the allegations Boazman put forth in his discrediting testimony in Folger v. Kendig. In the Nixon case, Boazman and Bushy were named as codefendants, and the court records reveal that the two were “partners in trade in buying and selling slaves.” Kendig seemed to support this assertion; he testified that “Boazman negotiated the sale from Mrs. Bushy to Nixon.” Surprisingly, Boazman did not deny this fact or qualify it at any time during the court proceedings. In fact, the lawyers who represented Boazman against Nixon also represented Mathilda Bushy in this case, and they confirmed the partnership between her and Boazman in their answer to Nixon’s charges.79 The Nixon case not only establishes Boazman and Bushy’s business connections, it also calls Boazman’s later denial of having known Bushy, and his dismissal of her slave-trading activities, into question. Furthermore, one witness testified that Boazman acted as Bushy’s agent in the slave sale that lay at the heart of the legal suit. Boazman testified in this case as well, and claimed to have “bid off the negro Willis” for Bushy and that Willis was “bought to be resold.”80 Buying slaves at the behest of a business partner, with the express intention of reselling those slaves for profit, qualifies by any measure as speculation or trading in slaves.

Kendig made his aunt’s economic investment in the New Orleans slave market abundantly clear when he was again called to testify in a suit that Edward Moore filed against her in 1857. He told the court that before buying and selling slaves for Bushy, he was a drayman and had much of his money invested in his drays and mules. Then he became interested in doing business with her, and she gave him the authority to use her money to buy groups of slaves and resell them on her behalf. As part of their agreement, Bushy allowed Kendig to retain half of the profits he earned when he resold the slaves, and he deposited her half in the bank.81 Kendig’s testimony also suggests that she was not new to the trade in human flesh; she was already profiting from the slave trade before he decided to take his chances on slave speculation. In fact, she had been buying and selling slaves without the aid of a proxy for years before Kendig became her agent and business partner. Bushy also appears in numerous court cases in which purchasers sued her for selling them diseased or otherwise “faulty” slaves. She also owned a slave yard.82

Bernard Kendig is well known to historians because he purchased enslaved people who were allegedly unsound in some way and knowingly resold them as healthy and sound, a shady practice that earned him a nasty reputation among fellow slave traders.83 Mathilda Bushy’s court records show that she, too, engaged in this practice. Was Kendig the mastermind behind this underhanded strategy to maximize profits in the slave market? Or did he learn from his aunt Mathilda? Was Mathilda Bushy a devoted aunt looking after her nephew’s financial interests and well-being? Or was she a woman who sought to engage in and exploit the gains that could be had in the lucrative trade that her nephew practiced? Mathilda Bushy did not leave behind her own answers to these questions, but from the records that do exist, it is evident that she operated in many of the same ways as did other individuals engaged in the slave trade. In fact, Kendig and Bushy’s partnership virtually mirrored an agreement which Boazman struck with Elisha Cannon in 1850: “Boazman was to receive 1/3rd the proceeds of buying and selling, and . . . Cannon was to furnish the capital.”84

The familial ties that undergirded Kendig and Bushy’s partnership resembled the ones that existed between male members of the notorious Woolfolk family, who used kinship ties to create a slave-trading network that operated in the most lucrative, geo-strategically positioned slave markets in the South. In addition to the Woolfolks, numerous cases exist of speculators forming similar partnerships with their kin.85 Similar partnership agreements also reveal that Mathilda Bushy’s decision to provide Bernard Kendig and James Boazman with the funds to purchase slaves, and her agreement to let them sell such slaves on her behalf, were not unusual either.86 Individuals like Bushy and Kendig structured their slave-trading partnerships in a variety of ways intended to draw on the strengths of each partner and benefit all parties. When difficulties arose, they modified their arrangements accordingly.

The women who bought and sold enslaved people for personal use, sold enslaved people on behalf of others, engaged in slave speculation, and partnered with others to trade in slaves for profit were not the only women navigating southern slave markets. Slave-owning women who set enslaved women to work in their “negro brothels” also benefited from their engagement in slave-market activities, and their livelihoods brought the markets in slaves and sex together. Some historians have assumed that “white men’s sexual access to slave women . . . lessened the market for black prostitutes,” and other scholars who examine the fancy trade—the sector of the market that catered to white men who sought to purchase sexual slaves and concubines—position them as the only individuals who seized the economic opportunities that such a market presented. But this was not always the case, especially in cities like New Orleans.87

Nineteenth-century New Orleans was one of the most important port cities in the world. It also held the largest slave market in the South, and it had plenty of brothels and prostitutes.88 Historians have studied the city’s slave market and fancy trade, including slave traders’ sales of these enslaved women to individuals who operated southern brothels, as well as the relationship between prostitution, city politics, and economic growth.89 These discussions usually center on male actors. But even a cursory glance at newspaper reports of arrests for crimes related to prostitution and brothel keeping makes it clear that women constituted the majority of the accused. And stories about white women who benefited from their involvement in the city’s markets in slaves and sex offer a dramatically different view of the ways white women exploited enslaved bodies for profit.

In what the New Orleans Daily Picayune described as a “disgusting affair,” police arrested four “light colored” enslaved women on the charge of living in a “house of ill-fame.” They belonged to Mathilda Raymond, the keeper of the house. According to the Picayune, these women were not simply Raymond’s domestic servants; they were in her house for “the vilest purposes”—in other words, to engage in prostitution. Raymond’s neighbor Thomas Lynch accused her of “keeping a disorderly house” that was “the resort and residence of lewd and abandoned women.” He did not, however, mention that some of these so-called lewd and abandoned women were enslaved.90

Mary Taylor also operated what the local newspaper described as a “negro brothel” in New Orleans, and she owned at least four women who were employed there. In 1855, three of them—Margaret, Patsey, and Josephine—were arrested on the charge of keeping a disorderly brothel, which was probably Taylor’s establishment. In 1858, they, along with another of Taylor’s slaves named Theresa and several enslaved people who belonged to local residents, were brought before court officials for unlawful assembly and harboring runaway slaves in Taylor’s brothel. And in 1862, two of her female slaves were charged with conspiring with Taylor to “rope in” and rob a man, probably a client. Taylor and her two female slaves were subsequently arrested, seized by the police, and placed in the local jail. While Taylor was incarcerated, police officers took her house keys and searched her home for the money that she and her slaves had allegedly stolen. She accused the officers of taking more than five thousand dollars’ worth of gold, silver, and cash, a gold watch, a gold chain and locket, a set of diamonds and other jewelry, and a gold pen with an ivory holder. The stolen money and property would have the purchasing power of more than $160,000 today, part or all of which Taylor undoubtedly earned through the sexual labor of her slaves.91

It’s difficult to say how many brothel-keeping women operated during these years. In the early- to mid-nineteenth-century South, courts charged many women with crimes related to prostitution, such as “keeping a disorderly house,” but prostitution itself was not a crime. Thus, slave-owning women’s sexual exploitation of enslaved women often remains invisible. In addition, the authorities often held slave-owning women’s female slaves responsible for crimes such as brothel keeping, even though their owners were ultimately responsible for their engaging in such acts.92 The assistant recorder of the First District of New Orleans, for example, ordered an enslaved woman named Sarah to be whipped for the crime of “keeping a house devoted to unlawful purposes” and imposed a twenty-five-dollar fine upon her owner, Mrs. Bonsigneur. There is no indication of whether court officials contemplated whether Sarah kept this brothel for or at the behest of Bonsigneur, or whether Bonsigneur compelled Sarah to engage in the work against her will.93

When slave-owning female brothel owners like Mathilda Raymond and Mary Taylor purchased enslaved women and compelled them to serve as prostitutes in their establishments, they were acting as slave traders of a different stripe. Their commerce condemned the enslaved women they owned to sexual violence, and they orchestrated every assault their male customers made upon their female slaves, acts that moved beyond the typical atrocities of the fancy trade. When white men sold fancy girls to men who sought sexual gratification, they generally profited from these transactions once. But slave-owning female brothel owners sold the most intimate parts of these enslaved women’s bodies to their customers over and over again. The money enslaved women earned while enduring these violations was not theirs to keep; by law and by custom their wages belonged to their female owners. Some historians have argued that enslaved women chose to engage in prostitution because sexual labor paid more than other kinds of work. Perhaps this was the case for some enslaved women whose owners allowed them to hire themselves out in whatever way yielded the most profit. But the enslaved women whom white women compelled to engage in prostitution within southern brothels were not afforded the same pseudo-autonomy or opportunities to determine what kind of labor they would perform.

It is noteworthy that when historians discuss white men’s involvement in the fancy trade, they do not frame the sale of enslaved women for the purpose of sexual labor, or the men’s perpetration of sexual coercion and violence against these women, in the same way. Recent studies have focused on slave traders who raped “fancy girls” before their sale and then passed these women off to business acquaintances so that they could do the same. After they and their friends had raped these enslaved females repeatedly, their owners sold them to other men who wanted them for the same purpose. The white men who engaged in these behaviors never claimed that the enslaved women they sexually violated willingly participated in these sexual encounters. Nor do historians suggest that the enslaved females whom slave traders subjected to these violations wanted to be fancy girls, wanted to engage in sex with these slave traders, or agreed to be sold as sexual slaves.94 The question then must be asked: If we do not assume that the enslaved women whom slave-trading men bought, owned, sexually violated, and sold as sexual slaves were “freely” engaged in sexual slavery, then why should we assume that the enslaved women and girls who belonged to white madams and brothel keepers chose or consented to the same kinds of sexual violation? Acting as brothel keepers, white women initiated the sexual violence against enslaved women, and acting as mistresses of the household they personally orchestrated acts of sexual violence against enslaved women and men in hopes that the women would produce children who would augment their wealth. The formerly enslaved women who recounted these ordeals unequivocally described their experiences as nonconsensual. As Sharon Block has made clear, “choice” or “consent” within coercive contexts such as slavery are impossible to judge, but in the end, enslaved women had no choice.95

The slave market offered a range of possibilities for white women, and until now these women have been among the slave trade’s best-kept secrets. But white women’s invisibility within southern slave markets has little to do with their avoidance of or aversion to the commerce that took place there. In fact, white women were ubiquitous in slave-market dealings. Regardless of how they might have felt about the system, their slave-market activities brought them wealth that they would not have accumulated otherwise. Most did not verbalize their innermost feelings about the morality and justness of slavery in the records they left behind. Yet every time a white woman chose to buy and sell slaves, provide a slave trader with goods or services, or prostitute the bodies of the enslaved females she owned, she contradicted the sentimental or maternal view of white women’s relationships with slaves and the institution as a whole. Their decisions to buy and sell enslaved people helped sustain the institution of slavery and the domestic slave trade, severed relationships between enslaved family members, and broke emotional bonds that would never be mended. The slave-owning women who engaged in slave-market activities were far more than begrudgingly complicit bystanders on the margins of the peculiar institution. They had an immense economic stake in the continued enslavement of African Americans, and they struggled to find ways to preserve the system when the Civil War threatened to destroy the institution of slavery and their wealth along with it.