“HER SLAVES HAVE BEEN LIBERATED

AND LOST TO HER”

A year after Union forces began their occupation of New Orleans in the spring of 1862, Captain Tyler Read of the Eighth Division of the Third Massachusetts Calvary and his men made a discovery while they searched for “arms and munitions” on the estate of a French Creole woman named Madame Coutreil. They not only found contraband, they also uncovered a “small house, closed tightly . . . about nine or ten feet square.” It was, according to Read, a “dark and loathsome dungeon, alive with the most sickening stench that can be imagined.” Appalled, he exclaimed to Coutreil, “In Heaven’s name, what have you here!” and to this she replied, “Oh, only a little girl.” When Read ventured inside, he found “sitting at one end of the room upon a low stool, a girl about eighteen years of age.” She was “nearly white” and had an “iron yoke,” surmounted with three prongs “riveted about her neck, where it had rusted through the skin, and lay corroding apparently upon the flesh.” She had been languishing in this place for three months, and was “almost insensible from emaciation, and immersion in the foul air of her dungeon.” Her only “crime” was attempting to run away from her mistress, who, suspecting her of Yankee sympathies, hoped to keep her hidden away until the Confederate army had driven the Union soldiers away from the city. Madame Coutreil’s action signaled her staunch determination to hold on to the young girl she considered her property, regardless of the circumstances that threatened her, and slave-owning women like her, with the loss of all they owned.1

Slave-owning women continued to buy, sell, and hire enslaved people even as the country—half-slave, half-free—moved steadily toward civil war. The days when they would be at liberty to do so, however, were waning. Men and women across the nation viewed the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln on November 6, 1860, as a sign that abolitionists had won. They believed that he and his administration planned to implement changes that would lead to slavery’s dissolution. Many southern slaveholders immediately prepared to defend the institution at all costs. Within days of Lincoln’s election, two South Carolina senators, James Chesnut and James Hammond, withdrew from their seats. Then, on December 20, 1860, citing the free states’ persistent assaults upon slavery and the federal government’s failure to protect the institution from such attacks, South Carolina seceded from the Union.2 Congress moved quickly to stave off impending conflict. Members proposed a constitutional amendment that would have prevented the federal government from abolishing or interfering with slavery, but their efforts proved unsuccessful.3 By June 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee had followed South Carolina’s lead and seceded from the Union one by one. Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri (which, with West Virginia, formed in 1863, were known as the Border States) took a different course; they remained committed to the Union and by so doing, ensured that the federal government would uphold their right to keep enslaved people in subjugation.

On April 12, 1861, a month after Lincoln took office, South Carolina took the lead once again when the newly formed Confederate States Army attacked Fort Sumter, a federal garrison situated in the Charleston harbor, an act that launched the Civil War. Three days after this assault, Lincoln issued a proclamation which called forth “the militia of several States of the Union . . . to suppress” the growing rebellion in the South. He also commanded southern rebels “to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes within twenty days” of its issuance.4 The rebel states ignored his command and continued their resistance. To the shock and dismay of many slaveholders, enslaved people responded to this conflict between brothers by intensifying their own rebellion against their owners and the institution they sought to preserve.

Enslaved people had long abandoned plantations in search of freedom, and they continued to do so as the conflict grew. But now they began to run toward federal military forces, rather than away from them. Initially they were unsure that Union soldiers sympathized with their plight, and they were right to be cautious. Enslaved people knew that they were taking enormous risks by leaving their homes and appealing to Union officers for help and protection within federal encampments. Throughout the war, many Union soldiers proved that they were no allies to the enslaved. Many northern soldiers were as prone as their southern counterparts to accept denigrating ideas about free and bound African-descended people in their region, and these views affected their interactions with enslaved people in the South. Even in states that seceded, some slaveholders remained committed to the Union and joined federal military forces while staunchly defending slavery. For all the good Union officers often did for escaped slaves, others returned enslaved people to their owners, even after military policy forbade them to do so. Union soldiers and officers stole from enslaved people, raped and brutalized them, sold them and pocketed the profits, and kept enslaved people for themselves.5 Complicating the situation, Abraham Lincoln and his administration gave enslaved people no indication that fleeing from their owners and crossing Union lines would result in their freedom. To the contrary, both before and after Lincoln became president, he emphatically expressed his commitment to upholding slave owners’ property rights. Lincoln’s speeches repeatedly assured slaveholders that he had no intention of interfering in their domestic affairs, and after he was elected president he reinforced this assurance in the opening passages of his First Inaugural Address: “Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by accession of a Republican administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection.” The Constitution protected American citizens’ rights to hold people as property, and Lincoln routinely and publicly declared his intention of abiding by it. He also promised southern slaveholders that any “fugitives from service or labor”—the euphemism for enslaved people—would be returned to them.6 However much of this most slaves might have been aware of, all knew that it was safer to venture into Union occupied regions cautiously, and if they did not face immediate rejection and learned of no plans to send them back, they communicated this information to other enslaved people who hoped to cross Union lines. Over the course of the war, enslaved people fled to Union-occupied territories and federal encampments by the thousands.

One of the earliest examples of this extraordinary exodus began in the spring of 1861 under the auspices of the Massachusetts lawyer, businessman, politician, and Union general Benjamin F. Butler, who oversaw Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. As enslaved people found their way to Fort Monroe, Butler faced a dilemma that plagued other Union commanders as well: Should he allow these individuals to stay within Union lines, or should he return them to their alleged owners? Like many other Union officers, he wrote to his superior for advice. Up to this point general military policy aligned with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: Union soldiers were duty-bound to return enslaved people to those who claimed them. Risking censure, some Union officers and soldiers refused to do so. But Butler resolved his quandary in an ingenious way, one that allowed him to avoid reprimand. Versed in the laws of war, Butler knew that any property that rebels used to aid and abet an insurrection against the government could be seized as contraband. He reasoned that, because enslaved people were technically property under southern law, and Virginians were in a state of rebellion against the Union, enslaved people who came to Fort Monroe could be defined as contraband and thus liable to confiscation. He also reasoned that he and the soldiers under his command were not obligated to adhere to the Fugitive Slave Act because it applied only to states within the Union; since Virginia had seceded, the law was no longer applicable there.7

In spirit and intent, Butler’s policy was not aimed at abolition or ensuring the freedom of escaped enslaved people; only a month before Butler implemented it, he wrote to the governor of Maryland reassuring him that he was “anxious to convince all classes of persons that the forces under my command are not in any way to interfere with or countenance interference with the laws of the State.” To that end, he promised the governor that he was “ready to co-operate with your excellency in suppressing most promptly and effectively any insurrection against the laws of Maryland.”8 Defining enslaved people as contraband liable to federal seizure and use was a military policy designed to weaken southern resistance by compromising the slaveholders’ ability to use the enslaved people they owned to support and sustain the rebellion. Despite Butler’s intentions, however, his policy laid the groundwork for a series of congressional actions that did indeed have emancipatory effects.

General Butler’s solution to the problem posed by enslaved people crossing Union lines proved a palatable one for Congress. On August 6, 1861, it passed “An Act to Confiscate Property Used for Insurrectionary Purposes,” also known as the First Confiscation Act, which provided for the seizure of any property that individuals in rebellion against the Union used to support their insurrectionary efforts, including enslaved people. In quick succession the following year, Congress passed several acts of legislation that slowly but steadily weakened the institution of slavery throughout the Confederacy. In March 1862, Congress approved an additional article of war that forbade Union soldiers from returning enslaved people to slaveholders deemed to be in rebellion. In April, it passed a law that abolished slavery within the District of Columbia and compensated slaveholders for the financial losses associated with the emancipation of the enslaved people they owned. In June, a congressional act prohibited slavery in territories belonging to the United States and any territories that the government acquired in the future. The following month Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act. Together, these two acts freed all enslaved people who belonged to individuals residing in Confederate states, even slaves who were not compelled to aid the rebellion, barred Union officers from assessing the legitimacy of enslaved people’s claims to be free or claims that disloyal slaveholders put forth with regard to the ownership of runaways, and permitted the president to “employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion [and] organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare,” including enlisting enslaved and free men of African descent in the Union armed forces. More powerfully, the Militia Act granted freedom to the family members of African-descended men who served in any military capacity within the Union.9

While this congressional activity was taking place, two Union generals—John C. Frémont, who commanded the Union Army of the West, and David Hunter, who served as Commander of the Department of the South—exceeded their military authority by issuing general orders regarding the emancipation of all enslaved people in the states of Missouri, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Lincoln swiftly denounced and rescinded their orders, fearing that their unconstitutional assaults on the property rights of slaveholders, especially those who lived in Missouri, would compel the other three slaveholding states within the Union to secede.10 Yet even with Lincoln’s public renunciation, southerners across the region, not just in the Border States, understood Frémont and Hunter’s emancipatory proclamations as part of a more systemic effort to abolish the institution.

In September 1862, Lincoln removed virtually all doubt about the institution’s future when he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. In it, he offered Confederate states the opportunity to rejoin the Union as long as they were willing to “voluntarily adopt, immediate or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits.” As further incentive, Lincoln also provided for slaveholder compensation for any slaves who might be freed by state-level abolition. He gave Confederate states a hundred days to decide whether to accept abolition and rejoin the Union. If they chose not to do so, all enslaved people within their states would be “then, thenceforward, and forever free,” and Union military forces were ordered to recognize and protect that freedom. On January 1, 1863, finding that the Confederate states remained in rebellion (with the exception of Tennessee and a number of parishes in Louisiana and counties in Virginia which were under federal control) and unwilling to cede the institution of slavery willingly, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation. It freed all enslaved people in Confederate states but stopped short of abolishing the institution of slavery entirely. Enslaved people who labored in Missouri, Maryland, Delaware, and Kentucky, the slaveholding states that remained loyal to the Union, remained in captivity.11

Taken together, the Union troops’ arrival in southern communities, the flight of enslaved people toward federal forces, Congress’s legislative actions, and Lincoln’s proclamations signaled irreversible transformations in the institution of slavery. Slave-owning women were acutely aware of these actions, and historians have remarked upon the ways they dealt with the conflict, indulging in bouts of intense and prolific writing during the Civil War era. White southern women and girls wrote about cold and indifferent Union soldiers, the impact of prolonged food and supply shortages, the heartache and yearning they experienced because of loved ones’ absences, the loss of the men and boys who had fallen in battle, the challenges of rural isolation, widowhood, and even the difficulty of making the transition from using enslaved to using free labor.12 And interwoven within their diary passages and personal correspondence, slave-owning women also grappled with the economic impact the Civil War had and would have upon them as individuals who owned enslaved people in their own right.

After lifetimes shaped by slavery and persistent efforts to sustain it, the prospect of emancipation caused slave-owning women tremendous concern for reasons that rarely emerge in existing studies of their wartime experiences: it robbed them of their primary source of personal wealth by redefining enslaved African Americans as people, not property; placed them in positions of economic dependency; and forced them to establish restrictive relationships with those who still had financial resources, in order to survive. Slave-owning women also feared emancipation because it held the potential to destabilize and reallocate the power they exercised within their marriages and families, authority which was often vested in their ownership of property. The government’s emancipation of enslaved people made it all but certain that such women, who commanded a level of respect and legal and economic autonomy within their households and wider communities from their status as slave owners, might lose that status. Throughout the war, women who owned enslaved people shouldered the tremendous burden of dealing with its consequences.

Often alone and isolated on plantations and farms scattered throughout the rural South, slave-owning women lived most days of the war surrounded by millions of enslaved people who embodied their fiscal loss and defeat. Slave-owning women often saw the Civil War as a personal battle, one they deemed worth fighting not just as southerners resisting the Union advance onto their land, or as “soldiers’ wives” whom the government of the Confederate States of America (CSA) promised to care for in exchange for their menfolk’s military service and sacrifices.13 It was also a fight they vigilantly took on to ensure their own financial autonomy, economic stability, and survival. But like the Confederate soldiers who lay slain on the battlefields, slave-owning women lost their war—and most of their wealth along with it.

As slave-owning women observed the signs of slavery’s dissolution all around them, they devised a multitude of strategies to protect their financial investments. At their best, slave-owning women freed their slaves and hired them to work their land for wages. One slave-owning woman “liberated all of her people . . . about three years before the Civil War [ended], and give them a home as long as they lived.”14 But at their worst, they perpetrated brutal acts of violence against the people they hoped to keep in bondage. The majority opted for methods that fell between the extremes. However, all their strategies were contingent upon local circumstances: the states in which they lived, the presence or absence of federal troops, and whether they could call upon individuals within the federal government or military forces to assist them. In their efforts to retain possession of their slaves white women traversed treacherous wartime terrain as well as seemingly peaceful countryside that might become a bloody battlefield at any time. When their slaves escaped to Union lines, slave-owning women who lived in the Border States appealed to members of their communities, the federal government, and high-ranking Union officials for protection of their investments in slavery, help in reclaiming their human property, or compensation for their losses. In Confederate states, as Union forces drew closer to slave-owning women’s communities and homes, the federal military policies implemented in 1861 and 1862 allowed women who swore an oath that they were not in rebellion to claim and repossess any of their slaves who could be found within military camps. Slave-owning women who lived in areas that had not been infiltrated by Union forces still feared their arrival because they suspected that the enslaved people who remained in their possession would either run away, be confiscated by Union troops, or, if they themselves were secessionists, be emancipated.

To circumvent these threats, many slave-owning women packed up and moved themselves and their slaves out of the Union’s reach, a process referred to as “running” or “refugeeing.” Other women, like Madame Coutreil, imprisoned their slaves to prevent them from escaping and often intensified their brutality against them. As the federal government moved inexorably toward emancipation, some slave-owning women rightfully concluded that they could no longer hold on to the enslaved people they owned, so they sold them or relinquished their property rights in them and forced their former slaves off their lands. Eventually most slave-owning women came to terms with their financial losses and reconstructed their lives without slaves. But they did not let go easily or willingly.

As the Union forces occupied the South, enslaved people began to behave strangely, and began disappearing in greater numbers from their female owners. Such was the case for Eliza Ripley, who remarked upon the change in the behavior and comportment of an old enslaved woman she had known all her life: “Old ‘Aunt Hannah’ (that was my mother’s laundress long before I was born . . .) stood in her little cabin-door as straight as an arrow; she always complained of rheumatiz, and I don’t think I ever saw her straight before; but there she stood, with the air of one suddenly elevated to an exalted position, and waved me a ‘Good-by, madam I b’ar you no malice.’”15 Some slave-owning women found it hard to believe that their slaves would leave unless the Yankees had compelled them. Sarah Johnson Berliner assumed that her family’s slaves “didn’t want freedom.” A “squad of Union soldiers,” she maintained, had summarily forced “freedom on them” and “told them that the proper thing for them to do was to get out for themselves.”16 After the Union declared it legal in 1862 for federal troops to confiscate the property of those who served in rebel forces or aided and abetted the rebellion, women like Berliner saw the Union officers who were authorized to take their silver, furniture, food, and livestock as thieves, and they particularly resented the “theft” of their most valuable property, their slaves. It was one thing to take precious metals, household goods, victuals, and animals. It was quite another to take human beings who were doubly, and sometimes triply, valuable and whose bodies, production, and reproduction paid dividends. Union troops did sometimes seize enslaved people against their will, but over the course of the war it became clear that, even without Union troops’ influence, enslaved people were more than willing to leave their female owners in search of freedom.

Some women interpreted the changes in their slaves’ conduct, especially their flight to Union encampments and enlistment in the Union Army, as a personal affront. One formerly enslaved man joined the Union Army when he was seventeen, and he returned to his mistress’s estate while on furlough. She asked him, “You remember when you were sick and I had to bring you to the house and nurse you?” He replied that he did, at which she exclaimed, “And now you are fighting me!” He explained that he was not fighting her personally but to secure his freedom.17

Their enslaved escapees’ “ingratitude” was not all that grated. The women who remarked or reflected upon the actions of runaway slaves realized that as enslaved people fled, all the wealth bound up in their persons was lost. These were fears that many southerners shared. Mary Boykin Chesnut related a conversation she had with a physician as they watched a Confederate regiment conducting marching drills while their slaves stood by. The doctor told Chesnut that the enslaved people gathered there constituted “sixteen thousand dollars’ worth of negro property which can go off on its own legs to the Yankees whenever it pleases.” As a slave-owning woman, Chesnut would have been familiar with such estimations and the financial losses runaway slaves represented. Women like Chesnut were acutely aware of the tactics that slave owners were using “to keep the negroes from running off.” Another southern slave owner, Catherine McRae, wrote about some of these strategies, but she also noted that despite such efforts, “a boy of Madame Dilmas’ and of Mr. Ellison’s made their escape the week previously.” Southern women might not have wanted to face the fact that enslaved people did not need encouragement to leave them, but enslaved people’s words, actions, and even body language often compelled them to do so.18

Even the youngest slave-owning females felt the economic impact of the war as the people they owned slipped away. Mary Elizabeth Woolfolk was only twelve or thirteen in 1862, but she already owned slaves, and that year they decided to “go off on [their] own legs to the Yankees.” Over the course of the war, Woolfolk lost twenty-four men, women, and children. On April 1, 1862, only weeks after Congress passed the article of war forbidding Union soldiers and sailors from returning fugitives to their owners, four of the enslaved men Woolfolk owned left and allegedly allied themselves with the Union forces occupying Fredericksburg, Virginia. According to Woolfolk’s trustees, Union soldiers visited the plantation where she and her slaves resided later that year, and on August 3, 1862, they “had a long conversation with the negroes.” Shortly thereafter, another three of her male slaves left.19

Not long after Congress passed the First Confiscation Act in 1861, the Confederate Congress passed its own act in order “to perpetuate testimony in cases of slaves abducted or harbored by the enemy and of other property seized wasted or destroyed by them.” Although the act never specified to what end this testimony would be put, its passage implied an eventual Confederate victory and alluded to the possibility that such documentation might be used to compel the Union to compensate slave owners after the secessionists won the war. In October 1862, in conformity with the Confederate act, Eldred Satterwhite, the Woolfolks’ overseer; Jourdan and John W. Woolfolk, Mary’s trustees; and William Woolfolk provided sworn affidavits to the Confederacy’s Department of State attesting to the losses Mary suffered valuing these men at $9,300.20 Two years later, on May 24, 1864, more of Woolfolk’s slaves fled to the Union as federal forces passed through her community. This time, the women and children outnumbered the men who fled. One Robert Y. Henley captured this “family of negroes” belonging to Mary as they tried to “make their escape to the Yankees.” He returned them to Mary and her trustees paid him $500 in compensation.21

Mary Woolfolk was lucky; she could call upon a number of male relatives and at least one family employee to help her apprehend her slaves when they ran away. But by 1862, many white southern women were not so lucky. Their fathers, uncles, brothers, husbands, and sons were fighting on battlefields throughout the South, and they were left behind with little to no male protection. Despite the dwindling numbers of white men still residing in southern towns and on rural estates, or perhaps because of their absence, slave-owning women called upon members of their communities to help them reclaim their human property. When Joe and Alfred Shipley fled from the men who hired them, their owner, Emily Mactaviah, posted a runaway advertisement in which she offered an award of fifty dollars for each. Ann L. Contee, a large-scale landowner from Laurel, Maryland, suffered the loss of three of her male slaves over the course of two months. She, too, posted an advertisement in the Sun on the same day that Emily Mactaviah did, and offered a fifty-dollar reward for each man to the individuals responsible for apprehending them. Seven months after her slave Lewis disappeared, Esther Baker placed an advertisement in the Macon, Georgia, Daily Telegraph requesting help in apprehending him as well. Almost a year after Eliza Sego’s slave Hector escaped, she offered a twenty-dollar reward to the person who would take him to the local jail so that she could reclaim him there.22

These runaway-slave advertisements also underscore the ruptures in the families of enslaved people, separations that slave-owning women brought about, sustained, or exacerbated. When an enslaved man named Sam ran away from Mary Gilbert, she placed an advertisement in the Charleston Courier six months after he escaped. Although Gilbert lived in Cuthbert, Georgia, she advertised in the Courier because she believed that Sam would try to find his wife, who lived on Anna Rumph’s estate in Walterboro, South Carolina.23 In many of these advertisements, slave owners theorized that their slaves, especially the men, had fled toward Union forces or their encampments. Gilbert, however, believed that Sam’s love for his wife had motivated his flight.

Although it remains unclear as to whether any of these specific women were able to reclaim the enslaved men they owned, some women seemed to have done so. Jailors’ notices scattered throughout southern newspapers during this period suggest that members of slaveholding communities were still hunting white women’s runaways, placing them in local jails, and possibly collecting the rewards that these women offered.24

While southern men talked valiantly of fighting to protect “hearth, home, and womanhood,” the women they left behind demanded government and military protection for their households.25 In the absence of southern men, white women called upon both Union and Confederate officers to respect their rights to such security.26 But in many cases, the “protection” that slave-owning women sought was not predicated upon their fears that soldiers would do them bodily harm, but rather on their concern that these men would violate their rights to and possession of their slaves. When southern women requested that their menfolk be exempted from military service, for example, they often based their appeals upon the effect that these men’s absence would have on their slaves. Without white men around, they argued, the enemy might persuade the enslaved people they owned to accompany them or run away. In a letter that Mrs. P. E. Collins penned to Alabama governor John Shorter, for example, she informed him that she wrote on behalf of a community of large-scale female (and male) slave owners who were without a significant male presence and thereby left “in a very unprotected condition.” Her neighbor, Mrs. McMillan, was isolated “on her plantation with over 50 negroes, without a white male member in her family.” Another one of Collins’s neighbors, Mrs. Mollet, was left on her plantation with “over 100 negroes.” Mollet’s twelve-year-old son was the only white male on the estate. Collins also expressed concern for her elderly male neighbors. One of them, Mr. William Mollet, owned “three farms” and “over 500 negroes.” But Collins did not seem particularly interested in her or her neighbors’ personal protection; she did not mention any fear of violence. She was more interested in preventing contact between their slaves and Union forces because federal troops might “place temptations before them,” and it was “wrong for negroes to be left as they are.” Remarkably, Collins argued that all this potential trouble could be avoided if the governor exempted one white man, James Nunnalee, from military service. Apparently he was a “rigid disciplinarian” who instilled more fear in enslaved people than ten men combined.27

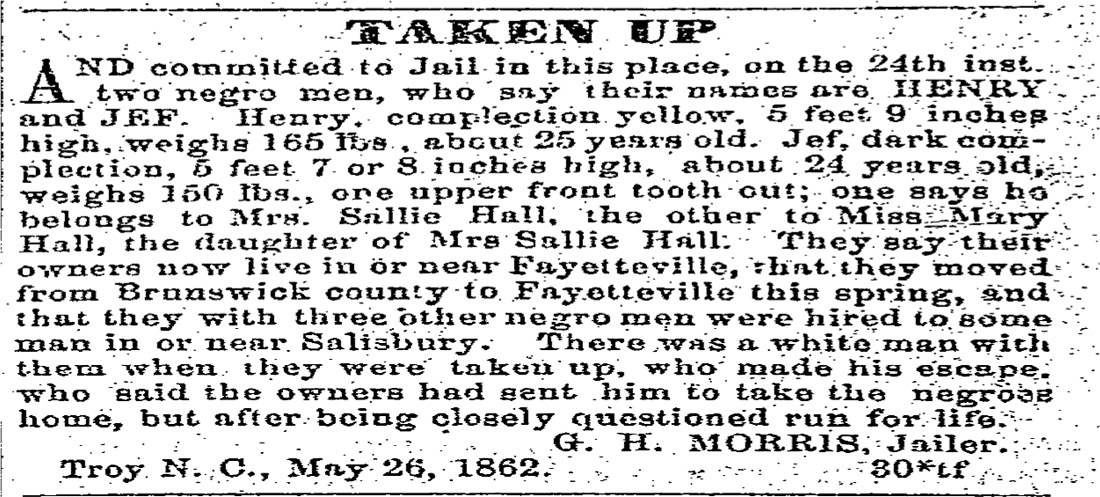

Jailor’s notice to Mrs. Sallie Hall and her daughter Miss Mary Hall to reclaim their slaves, Fayetteville Observer, June 2, 1862 (Nineteenth-Century U.S. Newspapers database, Cengage/Gale)

Slave-owning women who claimed loyalty to the Union also carped about the alleged or actual confiscation of their slaves and demanded that Union officers return the enslaved people they owned. Even when slave-owning women were unsure of their slaves’ whereabouts, they sought assistance from Union officers. Sometimes they asked male friends and kin to write letters to Union military officials on their behalf; at others they communicated with these officials directly. When the Union officer Colonel Wright confiscated Mrs. Robert Wagner Thomas’s two male slaves in 1862, her son-in-law, James M. Quarles, a lawyer, Tennessee congressman, and Confederate soldier, wrote a letter to General Grant on her behalf, which noted that she “had two negro-boys—carried off by Col. wright when his command left” her community. He also claimed that “these negroes are all the property she has . . . and they are her sole support.” From Quarles’s perspective, taking a woman’s only property and source of income was “a great injustice,” one which he believed “should at once be rectified.”28 Faced with the prospect of destitution, Thomas could think of no other alternative but to try to get her slaves back. Or at least that is how she presented her plight to Quarles and the Union official to whom he wrote.

Mrs. E. Stewart, who lived in the Border State of Missouri, claimed to be in dire straits as well, and she had two daughters to think about. In what seemed to be a last recourse, she directed her appeal for help to President Lincoln himself. In her letter of December 1863, she explained that the seven slaves she owned were all the property that she possessed, and they had left her. Two of the enslaved men had joined a regiment formed in Iowa; another had made his way to Camp Edwards in Massachusetts, where the regiment’s colonel issued him freedom papers and told him to remain within the confines of the camp. The four women and girls she owned, learning of this news, fled to Chicago and claimed their freedom based on the enlistment and freedom of the three formerly enslaved men who belonged to their mistress. With all her slaves gone, Mrs. Stewart had no source of income to care for herself or her two daughters. As a Union slave owner, Stewart asked Lincoln to either compensate her for the loss of her slaves or provide some “relief.” It is unclear whether he responded.29

Women like the Davidson County, Tennessee, slaveholder Mrs. S. F. Baker also sought out assistance and protection from Union officers, even after they found the enslaved people who had run away from them, and some of these men obliged them. In the last months of 1863, Hannah and Becky, two enslaved women Baker owned, ran away from her. Hannah fled to Nashville three months before Christmas, and Becky left to complete an errand for her mistress and never returned. Baker searched for Hannah and Becky until she found them, and at that time applied to Major General Lovell H. Rousseau for permission to take them home without molestation. Rousseau granted her request. He issued a written permit that allowed Baker “to take to her home the following Negro women Hannah and Becky (2).” The permit also warned individuals who might want to obstruct her passage that “the General Commanding directs that she will not be interfered with by any authority either civil or military.” Baker was in fact “interfered with”—Major John W. Horner stopped her after he witnessed the “humiliating spectacle” she created as she passed through town with Hannah and Becky in tow—but Rousseau’s permit “appeared to bear the sanction of superior Military authority,” so Horner allowed her to proceed on her way.30

This episode would not have raised ire among Union officers such as Horner had it happened two years earlier, but when he described the incident in a letter to another officer, Horner made it clear that Baker’s trek through Nashville with her enslaved fugitives, and Rousseau’s approval of her passage, were troubling for another reason. Rousseau’s protection permit noted that Baker was a “good loyal lady,” and by granting her safe passage he was also accepting Baker’s claim that Hannah and Becky were fugitives from her “service or labor.” Yet, in deciding on “the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person,” and by “surrendering up any such person to the claimant,” Rousseau was violating the additional article of war which Congress passed in March 1862, the Second Confiscation Act of July 1862, and the Emancipation Proclamation. By the time Rousseau issued Baker’s permit, it did not matter whether she was a “good loyal lady” or a secessionist, and it made no difference whether Baker had been Hannah and Becky’s lawful owner or not. By issuing Baker a permit granting her passage and protection from interference, Rousseau was countermanding federal laws which he was bound to obey. Perhaps Rousseau, a slaveholder from the Union state of Kentucky, believed that Baker’s right to property superseded the new federal laws. But no matter Rousseau’s reasons, by his authority Mrs. Baker went home with her slaves, in spite of the increasing threats federal law posed to her property rights.

Mrs. Thomas, Mrs. Stewart, and Mrs. Baker were typical of the majority of slave owners, who generally owned ten slaves or less.31 They were not large-scale landowners; they may not have owned any land at all. For them, the value ascribed to the people they owned and the labor those people performed constituted their only means of survival. Reclaiming their slaves was, they believed, a matter of life and death, and when Union soldiers “persuaded off” their slaves or when enslaved people ran away, these events marked the beginning of their financial ruin. By pleading with men who held the strongest positions of power, these women sought to stave off such an outcome.

After the United States Congress passed an act which emancipated “all persons held to service or labor within the District of Columbia by reason of African descent” in April 1862 and offered slave owners compensation for their slaves who had been freed, slave-owning women seized the opportunity to submit claims in order to receive some of those funds. The District of Columbia emancipation act required petitioners to “describe the person” they owned, and “state how the claim [to the slave or slaves] was acquired, when, from whom, and for what price or consideration,” and “if held under any written evidence of title,” to “exhibit [it] thereof, or refer to the public record where the same may be found.” Petitioners were also obligated to “state such facts, if any there be, touching the value of” their claim “to the service or labor of the person . . . and also . . . touching the moral, mental, and bodily infirmities or defects of said person, as impair the value of the petitioner’s claim to such service or labor.” They needed to submit an itemized “schedule” of the enslaved people they were claiming and sign and submit a “Form of the Oath for Verification of the Petition” that attested to their ownership and loyalty to the Union. The commissioners documented their work in daily minutes, which reveal that slave-owning women frequently appeared before them along with their slaves. The commissioners assessed these women’s loyalty to the Union and the value of their slaves. Some women, like Mildred Ewell and Fanny Ewell, appeared before the commission more than once because each time they brought only a few of the slaves they claimed. The commission called witnesses to testify on behalf of each petitioner, and in many instances women attested to other women’s loyalty and slave ownership.32

In response to the act, 1,065 Washington, D.C., slave owners submitted petitions for compensation; 429 were women, totaling about 40 percent of the claimants.33 Even an order of nuns, the Sisters of the Visitation of Georgetown, submitted a petition for compensation. Slave ownership, in fact, was not unusual among nuns living in the South. Emily Clark notes that the Ursuline nuns of New Orleans “owned enslaved people, bought them, sold them, and used them to work their plantations.” And when the District of Columbia emancipation act was passed, the Sisters of the Visitation divested themselves of their property just as other women did.34 Margaret Miller of Howard County, Maryland, appeared before the commissioners “with two servants” without ever filing the requisite petition for compensation, but she nonetheless hoped “to have them examined and valued.” Even though “she had not filed a petition,” the commissioners allowed her slaves to be appraised and let her submit a petition for compensation after the fact.35 Most of these women owned one or two slaves, but others, like Margaret C. Barber, owned more than the average slaveholder. She wrote to the federal government about her thirty-four slaves and included an itemized schedule that identified each by age, name, sex, color, and height; whether they were slaves for life or for specified terms; and the type of labor that they performed. The enslaved people in her holdings ranged from four months to sixty-five years in age and in color from “light mulatto” to “black.” They performed a variety of tasks: currying leather, laundering clothes, making shoes, cooking, and fieldwork.36 The government granted Barber’s request and paid her a total amount of $9,351.30 for all but one of her enslaved people, though this was undoubtedly less than the value she ascribed to the people she had once owned.37 Even so, Margaret Barber could count herself among the more fortunate of slave owners because she did not reside in a Confederate state where the federal government emancipated enslaved people without giving their owners a dime. She cut her losses and capitalized on the government’s promise.

Not every slave owner in the district followed Margaret Barber’s example. Some neither applied for compensation nor emancipated the enslaved people they held in bondage. So in July 1862, Congress passed another act, which allowed enslaved people to petition for their freedom in cases where their owners did not submit compensation claims. Out of the 108 petitions enslaved people submitted, 42 identified female owners.38 Many of these women lived in the Union state of Maryland or in Confederate Virginia—although a New Jersey woman named Julia Ten Eyck owned three of the slaves—and had hired out their slaves to residents within the District of Columbia. Upon learning that their slaves had submitted these petitions, the women quickly tried to file their own petitions for recompense before their slaves were granted their freedom. If they failed to do so, they would lose the opportunity to secure any funds associated with their slaves’ emancipation.

Similar requests could also be found in the slaveholding states that remained within the Union, especially from women whose male slaves enlisted in federal military forces. In Missouri, for example, around 11 percent of all claimants were women who requested compensation because their former slaves had enlisted in the 4th, 7th, 18th, and 19th U.S. Colored Infantry and the 5th and 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry. They made up about 5 percent of claimants for those whose slaves enlisted in the 1st, 4th, 8th, 12th, and 13th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.39

At various times during the war, women who were at the other end of the economic spectrum also wrote to military officials in hopes of rectifying wrongs that Union troops perpetrated against them. Mary Duncan, an elite absentee planter and slave owner from Staten Island, New York, took on the role of spokesperson for the Natchez, Tennessee, slave-owning community where her plantations were located. She complained that troops had ransacked property belonging to Unionists and carried off their slaves against the slaves’ own will. As a southerner who had remained loyal to the Union, Duncan had been given protection orders that were designed to prevent federal encroachment on her land and seizure of her property. Yet despite these “strong ‘protection papers’” Union soldiers had confiscated her property. She further alleged that the officers had forcibly removed and impressed the enslaved and freed men who labored on her plantations. Duncan claimed that her slaves were well treated and cared for, and that until the Union officers appeared, they had been willing to remain on her estate and work for wages. Throughout her letter, she questioned the authority of the men to take her property and demanded swift rectification of the problem, something she saw as her right as a loyal citizen of the Union. The Union official who investigated Duncan’s claims and personally interviewed the enslaved people in question told a different story. When he spoke to these allegedly contented laborers, they disputed Duncan’s claims, telling the officer that they were poorly treated, badly fed, and hardly cared for. In fact, they had left her estate willingly because they thought they would fare as well or better with the Union Army as they had with her.40

The following year, on October 27, 1864, Irene Smith wrote a letter to W. P. Fessenden, the secretary of the treasury, in which she assumed a gentler tone. She declared her unwavering loyalty to the Union and clearly delineated the property and goods she had lost to the officers serving under several Union colonels and captains. She also noted each time that she had made a personal request for protection. Later in her letter, it becomes clear why she so relentlessly petitioned the federal government. She and her daughter’s husband, Alexander C. Bullitt, owned four plantations in Mississippi and six hundred slaves. Irene Smith owned the majority of the land (three plantations), and the majority of the slaves who cultivated that land, as well.41 Irene Smith also had protection orders, and not unlike Mary Duncan’s, her orders gave no indication that she was concerned about the military harming her; the orders routinely and explicitly referred to her property. In her letter to the secretary, she wanted Fessenden to approve her purchase of supplies to sustain production on her plantations, “to be permitted at the earliest day possible to ship her cotton & produce to market, and return with her winter supplies, and pay all her outstanding Obligations.” She was trying to operate her plantation as usual, but the government was obstructing her ability to take care of business.42

Smith’s letter was written on behalf of the collective financial interest of herself, her daughter, and her son-in-law, and it offers important evidence about the relation of slave-owning women to their property interests. Smith’s son-in-law, Alexander Bullitt, was not illiterate; he was a state legislator and member of the New Orleans City Council. He was also a partner in Bullitt, Magne, and Company, the publishers of one of New Orleans’s leading newspapers, the Bee, and he later served as editor of another, the New Orleans Picayune. He was not a military officer; Smith did not need to be his advocate because he was present to witness the destruction of his property. Although he was in his early sixties, nothing suggests that he was incapacitated in any way that would preclude him from writing the letter. While Smith’s reason for writing the appeal on Bullitt’s behalf is not readily apparent from her correspondence, a comparison of the assets he held in the 1850 and 1860 United States federal censuses and references in his will show that the property Smith attributed to him was actually her daughter’s inheritance. In the 1850 census, Bullitt did not claim to own any property. Ten years later, however, he was listed as a member of Irene Smith’s household, and his occupation had changed from “editor” to “gentleman.” His property value changed, too; in 1860, he valued his real estate at $132,000 and his personal estate, which would have included his slaves, at $191,000. When he requested a presidential pardon from Andrew Johnson on December 15, 1865, he noted his place of residence as Longwood Plantation in Washington County, Mississippi, one of the estates that had belonged to Irene Smith’s late husband, Benjamin. Bullitt, who wrote his will in 1861 and died seven years later, bequeathed her two plantations, one of which was Longwood, along with “all the slaves . . . attached” to the plantations. He noted that the entire bequest was “the property formerly owned by my deceased wife,” Irene’s daughter Fanny L. Smith.43 All of these facts make it clear that Irene Smith’s interest in protecting her own property holdings and those of her daughter served as her motivation for writing her letter personally, rather than leaving it in Bullitt’s hands.

Confederate soldiers were equally prone to seize enslaved people who belonged to slave-owning women who were sympathetic to the rebel cause. And these women appealed to the Confederate government and military officials for assistance and recompense when they did. Female slave owners were not immune to Confederate impressment programs, and they were obliged to supply the Confederacy with the laborers it needed.44 The Confederacy paid slave owners wages for the enslaved people they commandeered, and Confederate officers, who oversaw the work that these enslaved men performed, maintained payroll sheets that recorded the particulars of the transactions. These sheets documented how many enslaved people Confederates took and from whom, any provisions they gave to these laborers, their terms of labor, where they worked, and the wages each laborer earned. Female owners’ names, or those of individuals these women appointed to act on their behalf, appear throughout these documents. Scores of enslaved men became ill, died, or disappeared while Confederate soldiers and military officials forced them to work, and in 1864 the Confederate Congress approved an act that provided slave owners with “payment for slaves impressed under State laws, and lost in public service.” Women who lost slaves to the Confederacy were among the petitioners who hoped to receive funds devoted to this purpose.45

In February 1863, Jacob, a twenty-four-year-old enslaved man owned by Mary Clark of Washington County, Virginia, was forced to work for the Confederacy on fortifications being built in Richmond. During his service, which lasted fifty-one days, he was exposed to inclement weather and deplorable work conditions that made him ill. On his way home, he developed pneumonia and eventually died. Responding to the recently approved Confederate House bill, Mary Clark submitted her request for compensation. She included attestations from neighbors, the physician who attended Jacob during his illness, and an officer who was responsible for transporting the slaves to and from the worksite to support her claim. The CSA Committee on Claims, the body to which her petition was referred, assessed Jacob’s value to be around $3,000 and sought permission to send her claim to the state of Virginia for further action.46 Other states within the Confederacy, such as South Carolina, had local compensation policies as well. According to Jaime Amanda Martinez, petitioners may never have received any of the compensation the Confederacy promised them, but these women’s decision to submit their petitions attests to their desire to hold their government accountable for the loss of the people they owned.47

Of course, not all women were willing to comply with the Confederacy’s impressment policies. Mary A. Tarrant of Perry, Alabama, who possessed an estate worth $93,800 in 1860, refused to give up the slaves requested under the state’s impressment policy.48 She was so averse to relinquishing her slaves that the men appointed to collect them had to return to her plantation with a posse. Once they identified the slaves who had been selected, Tarrant refused to give the soldiers provisions for the enslaved men they took. One of the men, J. W. Harrison, could not understand why Tarrant resisted so resolutely, especially because she was “better able to send hands to work on the defences than many others,” including “many widowed women,” who sent their slaves “cheerfully without a murmer and who did not own as many slaves as she does.”49 But from Mary Tarrant’s perspective, the answer was probably quite simple. These enslaved men were valuable to her as workers and as property, and the labor they would perform on behalf of the government could impair, if not destroy, that value. Mary Tarrant did not want to take the chance.

On neither side of the war did women make up the majority of claimants, but a number of reasons may account for this gender disparity. One may have been slave-owning parents’ tendency to give their daughters enslaved women and girls—who did not work on military fortifications and could not be enlisted as soldiers—rather than men and boys. Slave owners who submitted compensation claims to the federal government could only do so for enslaved men who enlisted in the Union forces; those petitioning the CSA government could only do so for enslaved men who died while impressed by the Confederacy. In the latter instances, enslaved male workers were in higher demand, as they were called on to build and maintain fortifications. Although enslaved women served both sides as “cooks, laundresses, officer’s servants, and hospital workers,” these women were barred from military service involving combat.50 Another reason for the apparent discrepancy is that the sex of many claimants could not be determined because military officials only noted first and middle initials instead of names in their documents. When accounting for these factors, it is quite possible that the total number of female claimants was higher.

Some women, finding that their letters and requests did not result in the return of their slaves or compensation for those that they lost, took matters into their own hands, traveling to Union encampments to find and repossess their slaves, delegating this task to others, or suing the men who refused to hand them over. As one enslaved man, Louis Jourdan, remembered, “I came with my family to Algiers, [Louisiana,] and was in the Contraband Camp [which accommodated enslaved people who left their Confederate owners] and living here awhile, my wife belonged to Madam Lestree, and she came or sent some one to the Contraband Camp and took my wife and children back to Bayou Lafourche.”51

Other slave-owning women went in search of the enslaved people they lost as well, frequently delegating this task to the men in their lives, either family members or employees. If, however, their proxies failed to rectify matters, some women pursued the issue themselves. In June 1861, Caroline Noland, a slave owner from Rockville, Maryland, sent her sons to take possession of an enslaved man she owned. She had allegedly “learned through a reliable source” that this enslaved man had crossed the border between Maryland and Virginia and hid himself in Camp Sherman, which was occupied by the 1st and 2nd Ohio Regiments of the Union Army. Noland’s sons returned empty-handed, claiming that Union officers had refused them access to the camp. But Assistant Adjutant-General Donn Piatt and Colonel A. McD. McCook, the commanding officer who permitted the search, denied her sons’ allegations. The officers had, in fact, granted Noland’s sons permission to search the camp for the missing slave, but they had not found him. It was only after their fruitless search that McCook’s men escorted her sons out of the camp. This was not the account Noland’s sons had given her, and based on their report, Noland took matters into her own hands. She wrote to Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the Union Army, seeking his assistance in the matter. In her letter, Noland asked Scott to “suggest and adopt such course in the premises as may enable me to reclaim my property.”52

As more enslaved people fled toward Union lines over the course of the war, similar conflicts played out time and again throughout the region. Union officers’ responses to slaveholders’ requests to reclaim the enslaved people they owned were heavily contingent upon federal and military policy, or, in cases like Caroline Noland’s, the absence of formal directives. When Noland submitted her appeal in June 1861, definitive federal policy instructing commanding officers on how to handle property claims like hers did not yet exist. These officers continued to seek out guidance until the U.S. Congress began taking swift action that left little room for doubt.

Some Union officers ignored slave-owning women’s letters, and some of those women sued them for refusing to give up their slaves. In 1862, Emily G. Hood, a Union loyalist, brought a civil suit against Colonel Smith D. Atkins in the Fayette County Circuit Court in Kentucky when he refused to allow her to repossess her slave, Henry, from his camp. Atkins would not appear in court or attend to the case until after the war was over. While he claimed that he based his decision upon the urgency and exigencies of war, his letter to a friend offered another reason: as a military commander, he refused to allow his “boys to become slavehounds of Kentuckians” or convert his regiment into “a machine to enforce the slave laws of Kentucky & return slaves to rebel masters.”53 Although he did not make this stance clear to his superiors, they agreed with him and allowed him to attend to his military duties rather than appear in court. As a slave owner in a southern state that remained loyal to the Union, Hood knew that federal policies protected her property rights, and this became even more clear after Lincoln issued his Preliminary Proclamation in September 1862. Although Hood’s legal suit was postponed, her decision to file her petition underscores her determination to preserve her investments in the institution of slavery, even if it meant taking a military official to court in the middle of the war to do it.

Quite reasonably, many slave-owning women feared that Union officers would confiscate their slaves, and they were just as concerned that they would lose the enslaved people they owned through flight. To reduce the likelihood of either happening, slave-owning women did what many other slaveholders did; they decided to “refugee.” Refugeeing involved relocating from a region threatened by Union occupation to an area deemed safer, and it was one way southerners hoped to protect their families against wartime destruction. But many slave-owning women refugeed specifically to remove their slaves from the Union’s reach and preserve their economic investments in the process. Wiley Childress’s mistress, Jane Boxley, for example, kept her slaves hidden until the war was over. Childress recalled that “durin’ de war may Missis took mah mammy en-us chilluns wid her ter de mountains ’till de war wiz gon.” Charlie Pye’s mistress, Mary Ealey, owned a number of slaves and “refugeed to Alabama trying to avoid meeting the Yanks.” But as Pye recalled, “they came in another direction,” so she had to change her plan. Mattie Lee’s mistress, Mrs. Baker, took her slaves from Franklin Parish, Louisiana, to Texas because “she was afraid the Union soldiers would take her slaves away from her.” At the war’s conclusion, however, Union forces infiltrated the area and “told de white people dat de slaves was free.” Lee’s mistress was seemingly unafraid of what the Union soldiers might do to her personally. She was more concerned about the financial harm they would cause if they took her slaves. Scores of women echoed these concerns and moved their slaves out of the way of Union forces. Hannah Kelly’s mistress Lou Downward also moved her slaves from Louisville, Kentucky, to Texas.54 Eliza Ripley and her family decided to refugee to Texas because they had “the feeling that the Federals could never get a foothold on its boundless prairies,” and “above and beyond all” they could “take refuge in Mexico if the worse came to the worst.”55

As these slave-owning women knew, refugeeing could be traumatic for enslaved people. Josephine Pugh, the sister of the Confederate general and Louisiana governor Francis T. Nicholls, recognized this in her account of the Civil War. While many families she knew fled encroaching Union forces and relocated to Texas, she and her family stayed put because they recognized “the aversion of the negro to breaking up and moving to a new country.” She and her family chose to remain and fight their battles in Assumption Parish, Louisiana, because they believed that their slaves’ “demoralization would be less complete at home.”56 Enslaved people had more than an “aversion” to refugeeing. It brought about the same kind of familial and community separation as did compelling them to leave their homes and move to the Deep South, separating families on the death of their owners, and slave sales. Slave-owning refugees often took their most valuable and able-bodied slaves with them and left those who were the least able to care for themselves—the aged, the infirm, and the very young—to fend for themselves. Refugeeing slave owners were frequently taking enslaved people away from the only homes they had ever known. Even when an owner refugeed within her home state, as Sallie Rhett did when she took her slaves from Stirling to Abbeyville, South Carolina, the relocation made it more difficult for long-lost family members to find each other. After the war Silvy Granville and members of her family, Sallie Rhett’s former slaves, moved back to Stirling, their home, to try to establish lives as freed people.57

Refugeeing was a risky strategy for both slave owners and the people they owned. Confederate soldiers and Union troops could impress able-bodied enslaved men and compel them to work on fortifications or in their encampments. Soldiers on both sides acted in ways that left slave-owning women without their most productive workers. Refugeeing was also difficult because Union officers knew about the practice and its purpose, and they could thwart a slave owner’s plans. Henry Miller’s mistress packed up about twelve of her slaves and began to trek them to “the woods country.” This was a fear-filled excursion, and Miller’s mistress became so anxious that she lost her sense of direction. In her confusion, she “done the worst thing she could” and “run right into a Yankee camp.” The Union soldiers questioned her slaves about where they came from, eventually freed them, and sent them back home.58

Staying put on a plantation, managing the affairs of the estate, and overseeing its cultivation and production, all in the face of military conflict, called for tremendous bravery on the part of white southern women. But gathering together their most valuable property and relocating to uncharted territory where they had never been before required a different kind of courage entirely. Nonetheless, many slave-owning women took the chance and set off, often without a significant white male presence; despite the dangers their decision might bring, they believed that preserving their financial well-being by moving their slaves beyond military and government reach was more important than the possible risks to their physical safety.

The thought of losing the people who embodied their most significant financial investments pushed some women to go beyond refugeeing to hiding their slaves, holding them in captivity, or imprisoning them. Whenever Ike Thomas’s mistress got word that the Yankees were approaching, she “would hide her ‘little niggers’ sometimes in the wardrobe back of her clothes, sometimes between the mattresses, or sometimes in the cane brakes. After the Yankees left, she’d ring a bell and they would know they could come out of hiding.”59 These enslaved children probably thought their mistress was allowing them to play a rare game of hide-and-seek, but there was no element of entertainment in the methods of “hiding” that some white women employed to conceal the whereabouts of the enslaved men and women they owned. Enslaved adults could not fit in the backs of closets or between mattresses, nor would they be likely to try to, so their mistresses held them captive in makeshift and local jails throughout the South.

Unlike the women who posted newspaper advertisements for enslaved people who had already fled, these slave-owning women sought to circumvent enslaved people’s escape before they could get the chance to run. During the war, Senator James Grimes of Iowa, who was also chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia, visited a jail in Washington, D.C., where he came upon an enslaved girl who was sitting “on the floor sewing her apron.” When Grimes asked her why she was there, the girl informed the senator that she belonged to Mary Hall, a woman who kept “the largest house of ill fame in Washington.” Hall had sent her to the jail “for safe keeping.”60

In 1863, Colonel William Birney, who acted as the superintendent of Maryland Black Recruitment, confronted a similar situation. He wrote to the headquarters of the Middle Department and 8th Army Corps to notify his superiors that the owners of twenty-four African American men who sought to enlist had imprisoned them in a local jail. The jail record noted the date of each prospective recruit’s imprisonment, the length of time he was there, his alleged owner, the individual he identified as his owner—who was often different from those who claimed him—and any other particulars that had led to each man’s captivity. Lewis Ayres was one of these prisoners. Although the jailor identified Greenleaf Johnson of Somerset County, Maryland, as his rightful owner, Ayres claimed that “Mrs. Briscoe, a secessionist lady of Georgetown, D.C.,” owned him. According to Ayres, Briscoe had brought him to Maryland a little over a year before Birney questioned him, and she did so “for fear he would be freed in the District.” This was not the first time she had imprisoned him for this reason. Ayres informed the superintendent that he had also been held in “Campbell’s Slave jail,” and his mistress had moved him to his current place of captivity because this jail charged her less to keep him. Despite all her efforts to keep him enslaved, Lewis Ayres enlisted and served as a private corporal in Company B of the U.S. Colored Troops, becoming a free man.61 Catherine Gardiner imprisoned her slave Augustus Baden in the same jail because he was prone to run away, or, as Baden might see it, for trying to secure his freedom. Nancy Counter imprisoned her slave William Sims for seventeen months in a Baltimore slave pen before Union forces set him free.62 Faced with the loss of able-bodied laborers who were also their property, many white women elected to lock them up instead of give them up.

Some women held their slaves captive in their homes and on their estates. When Annie Davis’s mistress refused to grant her her freedom and allow her to visit her relatives, Davis wrote directly to Abraham Lincoln in the hope that he would clarify whether she had a right to do so. “Mr president” she wrote, “It is my Desire to be free. To go to see my people on the eastern shore,” but “My mistress wont let me . . . you will please let me know if we are free. And what I can do. I write to you for advice. please send me word this week. Or as soon as possible and oblidge.”63 Davis did not make clear why her mistress had denied her her freedom and mobility. Perhaps she had observed the war-driven actions of her own or her neighbors’ slaves with dismay. Or perhaps she had read about or witnessed slaves leaving and not coming back and imagined the pecuniary loss she would suffer if Annie Davis did the same. She was certainly determined to present that from happening, even if it meant continuing to separate Annie from her family. After Fanny Nelson learned that she was free because of her husband’s enlistment in the Union Army, she informed her Kentucky owner’s grandchild of this fact. She also told the child that she would have to be paid for her future labor. The child relayed this information to Nelson’s mistress, who not only denied her her liberty and refused to pay her; she also “commenced locking her up of nights to keep her from leaving.” Nelson found a way to escape despite her mistress’s efforts to keep her enslaved.64

Other enslaved people did not have an opportunity to make an appeal to the government for their liberty, but they spoke about their troubles after the war was over. Before the war, George King’s female owner had built a log cabin on her plantation that she used as a jail for runaways. King’s mistress held her reclaimed runaways in this structure until they promised not to flee again. The “old jail was full up during most of the War” since most of the runaways refused to make that promise. When freedom came to the “two-hundred acres of Hell” where King lived, his mistress was still holding three enslaved people captive inside. Union soldiers discovered them chained to the floor.65

Slave-owning women often held their slaves captive because they were fearful of Union soldiers carting them off, but sometimes they had to worry about Confederate officers as well. Reflecting upon his mistress’s conduct during the war, Milton Hammond said that “during this time Confederate soldiers were known to capture slaves and force them to dig ditches, known as breastworks.” Hearing about such activities, his “mistress became frightened, and locked [him] in the closet until late in the evening.”66 As Hammond’s recollections illustrate, slave-owning women sometimes ignored politics to stave off the fiscal threats that came from both sides.

Slave-owning women could not always prevent enslaved adults from fleeing to Union lines, but they could hold fast to the children they left behind. Some white women claimed that they did so out of love for enslaved African American children, yet evidence shows that their refusal to reunite the children with their parents was ultimately an economic maneuver. After all, when enslaved parents left, slave-owning women lost part of their wealth, and they had no intention of losing more by giving up the children as well. In 1864, Colonel George H. Hanks appeared before the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, a government entity that was charged with evaluating the status of enslaved people who were freed by congressional acts and presidential proclamations. He testified about an unnamed African American soldier whose former mistress refused to give him his children. This soldier approached Hanks and “demanded his children.” Hanks responded that the children had a “good home,” suggesting that they should be left where they were. The formerly enslaved soldier appealed to Hanks as an officer and a father, apparently hoping that his words would humanize him in Hanks’s eyes: “I am in your service; I wear military clothes; I have been in three battles; I was in the assault at Port Hudson; I want those children; they are my flesh and blood.” Hanks was apparently moved by this appeal because he sent one of his officers to retrieve the children, but “the mistress refused to deliver them.” According to Hanks, “she came with them to the office and acknowledged the facts [related to her refusal]; she affirmed her devotion to them, and denied that the mother cared for them.” After an investigation, Hanks discovered that she had bribed the children “to lie about their parents.” Hanks delivered the children to their parents.67 This slave-owning woman went beyond simply refusing to relinquish her economic claim to a formerly enslaved soldier’s children; she paid them to tell untruths about the care their parents gave to them and positioned herself as their natural caretaker. And she almost convinced Colonel Hanks that she deserved to keep them.

Many Union officials took the matter of familial reconciliation seriously, and when white owners blocked a freedman’s efforts to reclaim his family, soldiers sometimes went to extremes to help him. An enslaved man who belonged to Ida Powell Dulany’s husband had escaped prior to the war, and as it raged he traveled back to Dulany’s estate accompanied by Union officers to find his family and bring them away. He asked Dulany to give him her assurance that he would be allowed to remove his family unmolested and then return safely to the Union encampment with his wife and children. She refused to grant him this assurance because he and his family no longer belonged to her. He went anyway, but when he did not return to the Union camp, officers arrested Dulany for failing to secure his safe return. She was released shortly afterward.68

Freed parents often had less luck in reclaiming their children. The Union Army impressed an enslaved man named Samuel Emery, and he subsequently began working on fortifications. The officials brought Emery’s wife to the place where he was employed, but they left their children in the owner’s possession. After both Emery and his wife had engaged in an “honest, industrious pursuit of a livelihood” for some time, they attempted to reclaim their children from their former mistress, Eveline Blair. She refused to give them back. When a Union officer, Urbain Ozanne, investigated the Emerys’ allegations in the spring of 1865, Blair, with “an utter disregard for the federal government and the earnest solicitations of the oppressed people,” as Ozanne put it, “indignantly spurned their united supplication uttering the most opprobrious epithets against the federal government and declaring the children should never be granted their freedom.”69 As other formerly enslaved parents tried to reconstitute their families, they faced similar, formidable odds.

Out of necessity, enslaved children had learned to detect even the slightest changes in their owners’ behavior, since such changes could affect their own well-being. Now, with the war threatening slave-owning women’s investments in the institution, these women became even more attentive to changes in enslaved children’s behavior. Some noticed that enslaved children were acting differently in the presence of Union soldiers. Without their parents or other enslaved adults around, enslaved children were uncertain about what to make of these strange men in their blue suits with shiny gold buttons, and their mistresses capitalized on their fears to discourage the children from flight. Many slave-owning women, such as Caroline Hunter’s mistress, resorted to scare tactics to keep enslaved children obedient. Hunter’s mistress told her that if she or any other slaves fled to the Yankees, the soldiers would “bore holes in” their arms “an’ put wagon staves through the holes” and make them “pull de wagons like hosses.” As far-fetched as this threat might seem, it was enough to keep Hunter from running away during the war, and it ensured a steady source of wartime labor for her mistress. Hannah Crasson also feared Union soldiers because her mistress claimed that “the Yankees were going to kill every nigger in the South.” In light of such deceptions, some enslaved children and adolescents deemed it safer to remain with the devils they knew than take their chances with heavily armed and unfamiliar ones.70

Simply by their presence, African American children imbued both their parents and their female owners with hope. For enslaved parents, their children’s very existence offered the prospect of a free future and the promise of a different kind of life, one shaped by liberty rather than bondage. Yet their owners’ hopes and financial futures lay in these children’s continued enslavement. Their growing, laboring, and potentially childbearing bodies promised white slave-owning women economic stability and continued prosperity. When determined African American parents confronted recalcitrant mistresses to demand their children, their contrasting visions for these young people involved more than conflicts over rights, authority, or custody; they were battles over property, fought on one side to redefine its meaning and on the other to preserve it.

Indeed, no matter how precarious the future of slavery seemed to be, slave-owning women and other southerners continued to buy and sell enslaved people throughout the war. Women bought and sold slaves during the war for the same reasons they had bought them before it, though some of their slave-market activities were intended to address the unique circumstances that the conflict brought about. Euphrasia Tivis, for example, “cheerfully sold” an enslaved female she owned to pay for a substitute who could take her husband’s place in the Confederate army.71

As the war progressed, many white slave-owning women finally recognized that no strategy could stave off its inevitable outcome. The time was approaching when they would no longer be able to hunt for their escaped slaves, hide them from Union soldiers, or hold them in captivity.72 They could not reclaim their slaves from Union encampments or seek compensation from either government for them. They had few options left. With their backs against the wall, some slave-owning women divested themselves of their holdings while they still could, selling enslaved people to anyone who would buy them or exchanging them for goods and supplies they needed or deemed more valuable. Henry Kirk Miller’s mistress sold his sister for fifteen bales of cotton. He recalled “hearing them tell about the big price she brought because cotton was so high. Old mistress got 15 bales of cotton for sister, and it was only a few days till freedom came and the man who had traded all them bales of cotton lost my sister, but old mistress kept the cotton. She was smart, wasn’t she? She knew freedom was right there.”73 Miller does not state precisely when “freedom came.” As Susan O’Donovan has shown, when freedom came and what it consisted of were largely contingent upon gender, region, the type of labor enslaved people performed, the presence of and proximity to Union forces, and a host of other factors. It also depended on the dispositions and objectives of the slave owners in question. In the southwestern region of Georgia that O’Donovan explores, she found that “distance . . . kept the war at arm’s reach,” and it also “kept freedom at bay.”74 Thus Henry Miller, who was born and raised in Fort Valley, Georgia, may have been referring to events that took place toward the end of 1865. Yet despite the delayed freedom that distance created, his mistress was clearly keeping herself abreast of the war’s progress, and when she considered whether to keep an enslaved girl who would soon be free or to trade her for cotton, she chose the more stable commodity.

This was a financially savvy decision on her part. Between 1860 and 1865, the price of a pound of cotton in the New York market rose from 11 cents to a high of $1.82 per pound. In 1865, a bale weighed 477 pounds, and each bale could potentially sell for $868. In one swift exchange, Miller’s mistress swapped a soon-to-be-free enslaved girl—a commodity without a price—for over 7,000 pounds of another. In theory, the exchange could have brought Henry’s mistress a profit of over $13,000.75 Perhaps the man who bought Miller’s sister possessed the same knowledge about the war’s impending end and the inevitable unraveling of slavery. But like many southerners who still believed that a Confederate victory was possible, he ignored it and made a very different economic choice, one for which he paid dearly.