INTRODUCTION: MISTRESSES OF THE MARKET

In 1859, after touring the antebellum South, the journalist and New York Tribune editor James Redpath attempted to explain for his readers why white southern women opposed emancipation. He believed that their sentiments were tied to a lifetime of indoctrination, “reared,” as they were, “under the shadow of the peculiar institution.” Slavery was “incessantly praised and defended” virtually everywhere they went, by everyone they knew, and in most of the publications they read. Their consciences, “thus early perverted,” were “never afterwards appealed to,” with the result that they saw no reason to change their views.1

Redpath assumed that white southern women did not know “negro slavery as it is” because their society shielded them from the institution’s horrific realities. Insulated by southern patriarchs, white women seldom saw slavery’s “most obnoxious features”; they “never attend auctions; never witness ‘examinations;’ seldom, if ever, see the negroes lashed.” More profoundly, they did not know that “the inter-State trade in slaves” was “a gigantic commerce.” Southern men revealed only “the South-Side View of slavery,” and if the women of the South “knew slavery as it is,” he was convinced, they would join in the protests against it.2

Redpath’s assumptions represented a commonly held patriarchal view. Yet narrative sources, legal and financial documents, and military and government correspondence make it clear that white southern women knew the “most obnoxious features” of slavery all too well. Slave-owning women not only witnessed the most brutal features of slavery, they took part in them, profited from them, and defended them.

Martha Gibbs was one of those women.

Litt Young, one of Gibbs’s former slaves, was interviewed as part of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), established by the Roosevelt administration in 1935. According to Young, Gibbs was a “big, rich Irishwoman” who “warn’t scared of no man.” She owned and operated a large steam sawmill on the Warner Bayou in Vicksburg, where it emptied into the Mississippi River. She also owned a significant number of slaves—so many, in fact, that she had to build two sets of “white washed” quarters with “glass windows” to house them all. She also built “a nice church with glass windows and a brass cupalo” for their worship. She fed them well, but she worked them hard, too.3

In step with other slave owners throughout the South, Gibbs employed an overseer to make sure that the people she kept enslaved performed the tasks delegated to them, but she also oversaw her overseer. Almost every morning, she “buckled on two guns and come out to the place” to personally ensure that things were running smoothly, and “she out-cussed a man when things didn’t go right.”4

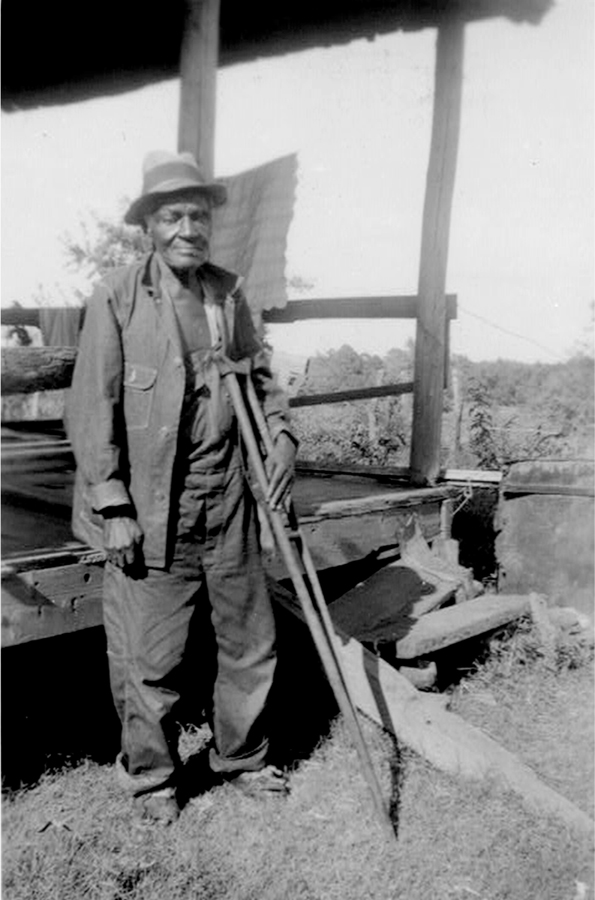

Litt Young (Federal Writers’ Project, United States Works Progress Administration, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

Twice married and once widowed, Gibbs would not permit either of her husbands to interfere with her financial affairs, including the management of her slaves. Even though her second husband was a reputable physician in Vicksburg, he had little influence over her or the slave-related activities on their plantation. Litt Young remembered Gibbs’s husband addressing her after witnessing the brutal whippings her overseer inflicted upon her slaves. He softly interjected, “Darling, you ought not to whip them poor black fo’ks so hard, they is going to be free jest like us sometimes.” Unfazed, she snapped, “Shut up, sometime I believe you is a Yankee anyway.” She was right. During the Civil War, he served the Union forces by treating injured soldiers.5

After the Confederates surrendered, and for reasons that remain unclear, local Union officers arrested Martha Gibbs and “locked her up in the black fo’ks church,” where they kept her under constant guard for three days, “fed her hard-tack and water,” and then released her. After the soldiers set her free, Gibbs freed her slaves, but only temporarily. One day, when her husband had gone to buy corn for his livestock, she gathered up some of her slaves, “ten, six-mule wagons,” and “one ox-cook wagon,” and set off with them. They walked about 215 miles, from Vicksburg, Mississippi, to “’bout three miles from Marshall,” Texas. She hired “Irishmen guards, with rifles,” to make sure that none of her “freed slaves” ran away during the journey, and when they stopped to rest, the guards tied the men to trees. Then, on June 19, 1866, one year after these legally free but still enslaved people “made her first crop in Texas,” Martha Gibbs finally let them go.6

Married slave-owning women like Martha Gibbs have received scant attention in historical scholarship. Historians have acknowledged that some southern women owned slaves, but they usually focus on the wealthiest single or widowed women. When they do encounter married slave-owning women in nineteenth-century records, they generally assume that the women’s legal status as wives prevented them from owning slaves in their own right. Historians rarely differentiate between married women who owned enslaved people in their own right and married women who merely lived in households in which they engaged with, managed, and benefited from the labor of the enslaved people that others owned. Historians rarely consider why slave ownership might have mattered to the women in question, to the enslaved people they owned, to slaveholding communities, to the institution of slavery, or, more broadly, to the region. Historians have neglected these women because their behaviors toward, and relationships with, their slaves do not conform to prevailing ideas about white women and slave mastery.

While it has long been recognized that southern slave owners were in the minority and that they were by no means a homogenous group, so much of what scholars know about women in the slaveholding South draws upon the diaries or letters of the most elite—those living in households that owned more than ten enslaved people. Historians have chronicled these lives, producing microhistories about an extremely small subset of an already small group of white southerners. Such studies should not be used to make generalizations about the majority of women in slaveholding communities at large; records indicate that the majority of slave owners owned ten enslaved people or less.7

Scholars who examine the authority that women held over their slaves frequently focus on the women’s obligatory, rather than voluntary or self-initiated, management and discipline of enslaved people. They argue that women could not be true “masters” of slaves. Rather, they were “fictive masters.” Even when they possessed the skills and the gall to manage their slaves, these historians argue, they typically did not relish their power: they did not view their activities as “slave mastery,” and neither did southern laws and courts. This was especially true when it came to violent forms of discipline. White women might punish enslaved people; they might even be brutal and sadistic, but they fell short of wielding a “master’s” power. In sum, these scholars argue that slave-owning women’s acts of violence differed from those of slave-owning men.8

By extension, many of these scholars flatly reject the idea that white married women could adeptly manage enslaved people without the assistance of men, be they white or black, or that, aside from a few exceptional women, they could possess the acumen to do so while also effectively running plantations. Married women, they argue, begrudgingly assumed roles as “deputy husbands” and “fictive widows” when their husbands were away. When their men were present, these women happily and enthusiastically relinquished such responsibilities and exhorted their men to handle what one historian has called a “man’s business.”9 And in the view of more than a few historians of American slavery and the domestic slave trade, this was especially the case when it came to the business of buying, selling, and even hiring enslaved people. These scholars claim that the nasty and unseemly business of transacting for human beings was considered ill-suited to white ladies.10

In They Were Her Property I build upon these earlier studies, but I also depart from them in significant ways. I focus specifically on women who owned enslaved people in their own right and, in particular, on the experiences of married slave-owning women. In addition, I understand these women’s fundamental relationship to slavery as a relation of property, a relation that was, above all, economic at its foundation. I am not suggesting that this was these women’s only relationship to the institution or that the economic dimension of their relations overrode other aspects of their connections to slavery; rather, I argue that pecuniary ties formed one of slave-owning women’s primary relations to African American bondage.

The story of these women’s economic investments in slavery, I shall argue, tells us much about their economic roles in the institution and the process of nation-making that historians did not know (or want to know) about before. The economic historian Sven Beckert has argued that “slavery was a key part of American capitalism” and that “slave plantations, not railroads, were in fact America’s first ‘big business.’” If we examine women’s economic investments in slavery, rather than simply their ideological and sentimental connections to the system, we can uncover hitherto hidden relationships among gender, slavery, and capitalism.11 The products of these women’s economic investment—the people they owned—including the wages enslaved people earned when hired out to others, the cash crops they cultivated, picked, and packed for shipment, and the babies they nursed, were fundamental to the nation’s economic growth and to American capitalism.

Historians who explore slavery’s relationship to capitalism generally focus on the roles that men played in the development of both.12 But if we considered the very real possibility that some of the enslaved people these men compelled to work in southern cotton fields actually belonged to their wives, the narrative about American slavery and capitalism would be strikingly different. And when we consider that the enslaved people women owned before they married or acquired afterward helped make the nineteenth-century scale of southern cotton cultivation possible, the narrative of slavery, nineteenth-century markets, and capitalism as the domain of men becomes untenable.

Adam Smith, the preeminent eighteenth-century economist, argued that a married woman’s financial dependence upon her husband bound her “to be faithfull and constant” to her spouse.13 In line with Smith’s thinking, we tend to imagine marriage as a colonial or nineteenth-century woman’s primary, if not her only, avenue to financial stability, and for many women this was true. But circumstances existed in which white men were economically dependent upon, even indebted to, the women they married, and this was a widely recognized fact, even in the North. Abigail Adams, the second First Lady of the United States, advised her son John Quincy to postpone marriage until he had accumulated enough property to ensure that he would not be wholly dependent upon the wealth his future wife might bring into their household. When John Quincy hinted at the possibility that he might indeed marry for money, Abigail firmly advised him never to “form connextions” until he saw “a prospect of supporting a Family.” In his response, John Quincy assured his mother that he would never be “indebted to his wife for his property.”14

In the South, slave-owning women possessed the kind of wealth that prospective suitors and planters in training hoped to acquire or have at their disposal. Why else would John Moore crassly tell his cousins Mary and Richard that “girls … bait their hooks with niggers and the more they can stick on the better success” they would have in securing a worthy husband? According to John Moore, even young women outside the ranks of the most elite slaveholders, who typically owned twenty or more slaves, could increase their chances of marrying well if they owned a few. He told his cousins that “the girl that has but one or two will get a few nibbles and occasionally catch a trout, but not until he has tried and failed at the larger hooks.”15 As this correspondence suggests, some men entered their marriages with little or no wealth, and their unions with propertied women became their primary avenue to financial independence.

A white man’s pecuniary circumstances could change drastically upon marriage because state and local laws generally gave husbands control over the property their wives brought to the marriage. Simply by marrying a woman with property, even if she maintained control of it, a man could improve his position: husbands often borrowed money from their wives and used the enslaved people their wives inherited to cultivate the lands they bought with those loans. Legal petitions are on record in which women describe themselves as their husbands’ creditors and financiers. Many of these women did not accept the loss of their legal claims to the property they brought into their marriages. In fact, many married female petitioners described their slaves as property they still owned and controlled, considering their husbands’ control temporary—and as we shall see, the courts often agreed with them. Enslaved people also testified to the ways such ideas shaped marital relations in white households. Thus, in many respects, married women, their slaves, and their other assets made their husbands’ commercial endeavors possible and enabled slavery to thrive in ways it might not have without those women’s economic investments in the institution.

I call the women in this book “mistresses of the market.” But what exactly does that mean? Scholars such as Jennifer Lynn Gross argue that nineteenth-century southern “mistresses” assumed roles that were restricted to the “dependent positions of daughter, wife, and mother,” and that “daughters relied completely on their fathers for their public identities, and this dependence transferred to their husbands upon marriage.”16 Because of these constraints, historians contend, white southern women had little to do with enslaved people beyond the household. They generally did not personally own slaves, and when they did, their husbands exercised control over them. Southern mistresses were not adept at slave or plantation management unless extenuating circumstances, such as a husband’s prolonged absence or death, compelled them to be. Even then, such women typically complained about having to take on “masculine” responsibilities. When it came to legal and financial matters, the nineteenth-century southern “mistress” resembled the colonial “gentlewoman” who was “less likely to know about, or assist in, the management of her husband’s affairs or to be involved in trade or business of any sort.”17 These women tended to defer to their spouses and male kin in legal and financial matters, and if they did not want to, scholars maintain, law and custom forced them to do so. In virtually every dimension of life, then, southern mistresses were held to be at the mercy of white men.18

In this book I employ the term mistress in a radically different way, one that aligns more closely with its original meaning. In Western Europe, a mistress was “a woman who govern[ed]; correlative to [a] subject or to [a] servant.” She was “a woman who ha[d] something in [her] possession,” and according to the historian Amy Louise Erickson, that something was capital. A mistress also exercised “dominion, rule, or power.”19 The term mistress did not signify a married woman’s subservient legal position or a woman’s subordinate status to that of a master. By definition and in fact, the mistress was the master’s equivalent. Thus, when South Carolina legislators declared that “every master, mistress or overseer, shall and may have liberty to whip any strange negro or other slave coming to his or their plantation with a ticket” (the pass an enslaved person had to carry when he or she left the master’s estate), they were not imbuing mistresses with subordinate powers or power in their husbands’ stead; they were recognizing the comparable powers and authority that these women possessed.20 The term used to describe women’s control of subordinates was not mastery but mistress-ship. Moreover, when formerly enslaved people talked about the control that their masters and mistresses exercised over them, they often accorded equal power to men and women. Robert Falls recalled that when his “Old Marster and Old Mistress would say, ‘Do this!’ … we don’ it. And they say ‘Come here!’ and if we didn’t come to them, they come to us. And they brought the bunch of switches with them.”21 Slave-owning women may not have referred to their management of enslaved people as “slave mastery,” but they used the same strategies and techniques that male planters described in the “Management of Negroes” columns that appeared in the pages of agricultural periodicals throughout the South. When we listen to what enslaved people had to say about white women and slave mastery, we find that they articulated quite clearly their belief that slave-owning women governed their slaves in the same ways that white men did; sometimes they were more effective at slave management or they used more brutal methods of discipline than their husbands did.

The Western European mistress was defined in another important way that is relevant to the women I discuss in this book and the central argument I make. A mistress was a woman who was “skilled in anything,” and when it came to the nineteenth-century market in slaves, southern women were savvy and skilled indeed. They studied the slave market and evaluated its fluctuations. They blended into the crowds that surrounded public auction blocks and courthouse steps as enslaved people were exposed for sale. They glided past local slave markets and walked along the streets where slaves were openly displayed. They sat in the front rows of the more aesthetically pleasing slave-auction venues dressed in luxurious silks, satins, and jewels. They stood side by side with other women at public auctions to watch traders and auctioneers sell enslaved people to the highest bidders. But these women did more than observe the procession of black bodies placed before prospective buyers on sale days.

White southern women conducted transactions with slave traders, who bought slaves from and sold slaves to them as they lounged comfortably within the confines of their homes. And they were not meek in their bargaining: traders often wrote to one another with tales of slave-owning women who harassed them about pending transactions. Other men described women who entered slave markets to see what kind of “merchandise” slave traders had for sale. They recalled how these women would interrogate and inspect the slaves who piqued their interest, and they commented on women who bought and took enslaved people home. Slave-owning women brought legal suits against individuals, both male and female, who jeopardized their claims to human property, and others sued them in kind. They bought and sold slaves for a profit, and, on rare occasions, they owned slave yards.

As the historian James Oakes has pointed out, some African-descended people, indigenous people, and women were viable and active members of the master class.22 Race and gender, however, created unique constraints that these groups had to endure, adapt to, or circumvent. The experience of slave ownership was different for married women. The legal doctrine that placed their persons and their goods under their husbands’ control compelled them to take extra steps to secure their separate ownership and management of enslaved people, processes that were not required of men. Their legal subordination to their husbands also meant that women could potentially find themselves in court when spouses, kin, and community members jeopardized or violated their property rights or attempted to exploit them. These special contingencies could prove to be insurmountable impediments for southern women who might hold or want to hold legal title to enslaved people and who might want to exercise control over the enslaved people they owned or came to possess. But the women discussed in this book were not dismayed or deterred by the legal challenges. They and their families took the steps necessary to own and maintain control over the enslaved people given to them by loved ones or bought or acquired upon, during, and after marriage. Such steps were neither simple nor easy. That women decided to take them to secure slave property for their own use and benefit reveals their deep economic interest and investment in the system of American slavery. Their willingness to do these things suggests that they were more, not less, invested in slavery and its growth than some men were.

The historian Susan O’Donovan has argued that the South was a region “where the slaveries were many” and where “freedom often assumed numerous and differently gendered shapes.”23 Although she was speaking about the experiences of enslaved people in particular, her conceptualization of many freedoms is also useful for understanding the circumstances that the white women discussed in this book confronted and created. For them, slavery was their freedom. They created freedom for themselves by actively engaging and investing in the economy of slavery and keeping African Americans in captivity. Their decisions to invest in the economy of slavery, and the actions that followed those decisions, were not part of a grand scheme to secure women’s rights or gender equality. Nevertheless, slave ownership allowed southern women to mitigate some of the harshest elements of the common law regime as it operated in their daily lives. Women’s economic investments in slavery, especially when they used legal loopholes to circumvent legal constraints, allowed them to interact with the state and their communities differently. And these women’s actions challenge current understandings of white male dominance within southern households and communities in the antebellum era.

In countless ways, then, slave-owning women invested in, and profited from their financial ties to, American slavery and its marketplace. Yet they rarely documented those economic connections. Others, however—white men and enslaved people themselves—did make note of and speak about their activities, which the Civil War made tenuous and to which abolition eventually put an end.

When FWP employees traveled through the South searching out glimpses of the past through their interviews with formerly enslaved African Americans, individuals like Litt Young discussed and identified their female owners. Serving as the metaphorical flies on the walls of southern households, formerly enslaved people talked about some of the most violent, traumatic, and intimate dimensions of life for those who were bound and those who were free. They heard and saw things that typically remained obscured from view, details that white slave-owning couples often left out of personal correspondence or public communications—that is, when they were able to write at all. Many of the slave-owning women I discuss in this book contended with some form of illiteracy; they either were unable to read and write or possessed the ability to do one but not the other.24 Enslaved and formerly enslaved people’s recollections about their female owners thus serve as some of the only archival records about these women to survive.

The nature of slavery all but guaranteed that formerly enslaved people would relocate many times, be compelled to work in different regions of the South, and possibly cultivate different crops in different climates over the course of their lives. The government employees who interviewed them worked from a questionnaire that did not include any questions about whether and how their experiences of enslavement changed as they moved across the South. While some formerly enslaved people did offer details “off script,” others simply chose to answer the questions posed.25

Some historians caution scholars against relying upon the testimonies of formerly enslaved people gathered in the mid-twentieth century. They contend that formerly enslaved people could not possibly have understood what slavery entailed because, after all, most of them were only children when slavery thrived in the South. Furthermore, they suggest that even if the survivors were old enough to have experienced their bondage in all its dimensions, it was unlikely that they remembered details clearly after such a long period of time; some seventy years had intervened between emancipation and the interviews. Moreover, most of the interviewers were southern whites, many the descendants of slave owners, and in the face of such people formerly enslaved interviewees probably felt intimidated and confused, and were less likely to offer candid accounts of what they endured in bondage or the people who kept them enslaved.26

That many of the people interviewed in the 1930s were children during their bondage was certainly the case, but it was not true of all of them. Some women, like Delia Garlic, “wuz growed up when de war come” and “wuz a mother befo’ it closed.” She was a centenarian when Margaret Fowler interviewed her in 1937. Similarly, Willis Bennefield believed that he was “35 years old when freedom [was] declared.” The WPA interviewers talked to many others like them.27

Additionally, although some formerly enslaved people were young when they were freed, it is unlikely that they could forget what psychologists and gerontologists call “salient life events”: pivotal experiences such as marriages, births, deaths, and, in the context of slavery, brutal beatings, sexual assaults, or familial separations that occurred after the sale or relocation of loved ones. Delicia Patterson, for example, was fifteen when her owner brought her “to the courthouse,” and “put [her] up on the auction block to be sold.” When Anne Maddox was thirteen, she was part of a speculator’s drove that traveled from Virginia to Alabama. Tom McGruder, “one of the oldest living ex-slaves in Pulaski County,” was “eighteen or twenty” when he “was sold for $1250.” These formerly enslaved people could not forget such events or the slave owners who initiated them and were ultimately responsible for the trauma that followed. Moreover, remembering certain details about their bondage could mean the difference between life and death for such people both during and after slavery. As enslaved and formerly enslaved people navigated the southern landscape, their safety, and sometimes their very lives, often depended upon their ability to produce passes (“tickets”) which accurately identified their owners, among other things.28 And their continued ties to the white families that previously owned them could spare them some of the racial violence that characterized Reconstruction in the South.

Formerly enslaved people may have found their interviews tense and uncomfortable, but many of them spoke openly of the tragedies and traumas of slavery nonetheless. Despite the possibility of provoking a violent reaction, formerly enslaved people spoke with their white interviewers about matters as intimate as cross-racial sexual violence, white paternity of enslaved children, and incest, and as horrifying as torture inflicted by their masters and mistresses or former owners who murdered enslaved people. They argued that these were things, along with the constant threat of sales that would remove them from their homes and families, that they could never forget, regardless of how much time had elapsed.29

Furthermore, the interviewees did not always give their testimony in isolation. Family, friends, and individuals who came by to assist some elderly formerly enslaved people with daily tasks were often present during their interviews. When the FWP employee Zoe Posey visited Mary Harris to interview her about slavery for a second time, she was confronted by Harris’s angry son, who initially prevented her from continuing her queries. He interrogated her about her intentions and proclaimed, “Slavery! Why are you concerned about such stuff? It’s bad enough for it to have existed, and when we can’t forget it, there is no need of rehashing it.” At such an outburst, Posey may have been the one who was intimidated during the encounter, not her interview subject.30 To be sure, formerly enslaved people often responded to questions about their enslavement with silence because they did not always want to remember or talk about their experiences. But thousands chose to do so despite their reservations. They told their stories in an atmosphere of intense racial hostility and in a region where simply refusing to step off the sidewalk when a white person passed by could result in their deaths. They believed that telling their stories was worth these risks. I honor their courage, heed their words, and foreground their testimony and remembrances in this book.

As I wrote, I grappled with whether to include terms like nigger that might be offensive to my readers and seem disparaging to my African American subjects. Ultimately, I decided to include the language used in these interviews because they are the best sources we have for understanding how enslaved people understood their lives and their worlds. In addition, making any changes to the text presented its own problems. Such revisions would sanitize the experiences of these formerly enslaved people and make it difficult for readers to understand how they perceived what had happened to them. They did not have to tell their stories, and they received little or nothing in recompense for their interviews. Nevertheless, they did tell their stories, and in the ways they felt most comfortable. In this book they speak in their own words.

Slave-owning women rarely talked about their economic investments in slavery, and they wrote about them even less. Their silence did not reflect their aversion to slavery or human trafficking. Many of them simply did not have the time or the skill to put their thoughts on paper, while those who did probably saw their pecuniary investments in slavery as commonplace and unworthy of note. This is their story.

No group spoke about these women’s investments in slavery more often, or more powerfully, than the enslaved people subjected to their ownership and control. They were the people whose lives were forever changed when a mistress sold someone just so she could buy a new dress. They were best equipped to describe the agony that shook their bodies and souls when they returned from their errands to discover that their children were gone and their mistresses were counting piles of money they had received from the slave traders who bought them. Only enslaved people could speak about their female owners’ profound economic contributions to their continued enslavement with such astonishing precision. This is their story, too.