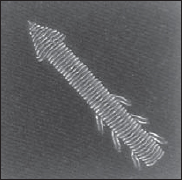

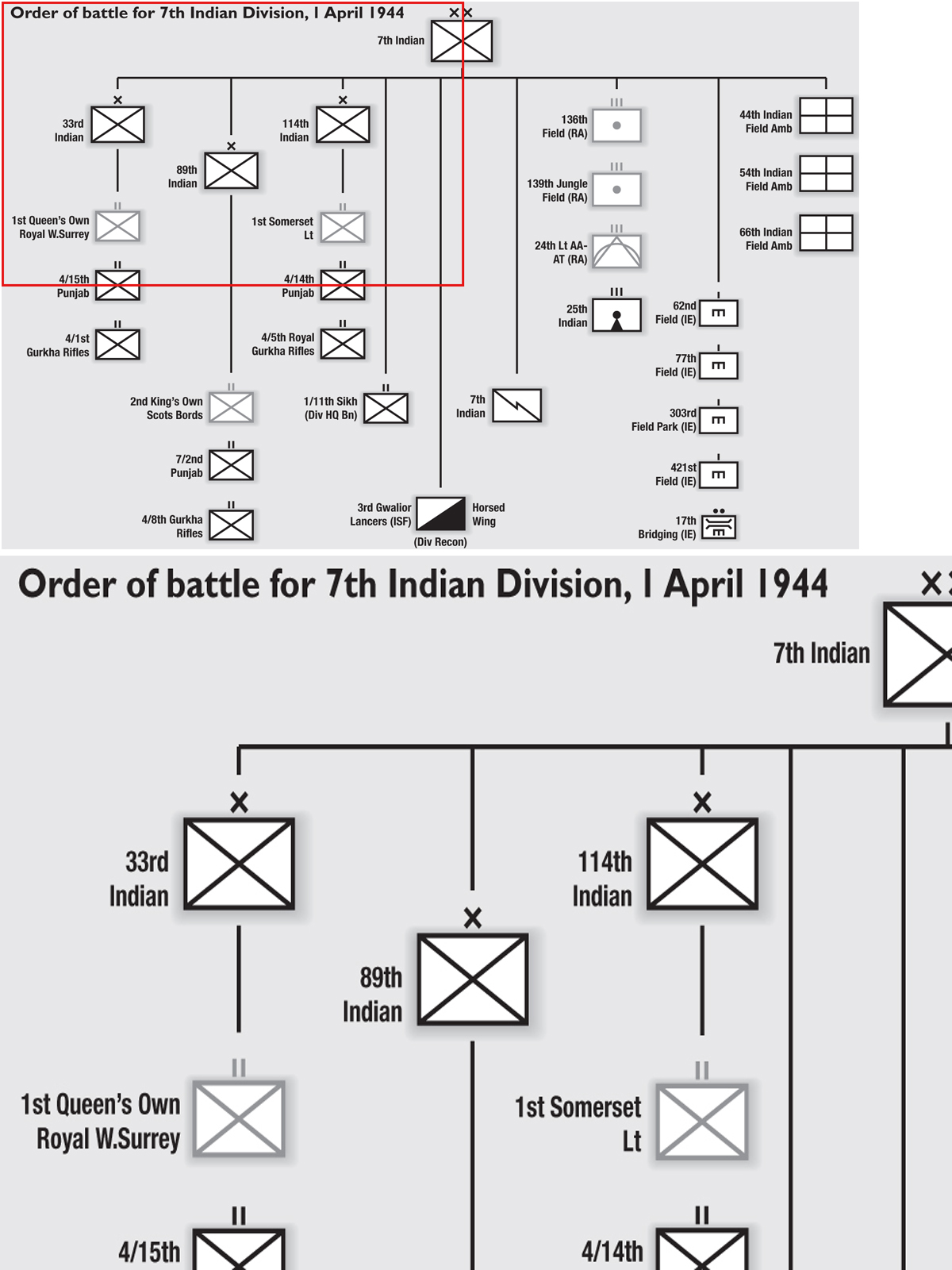

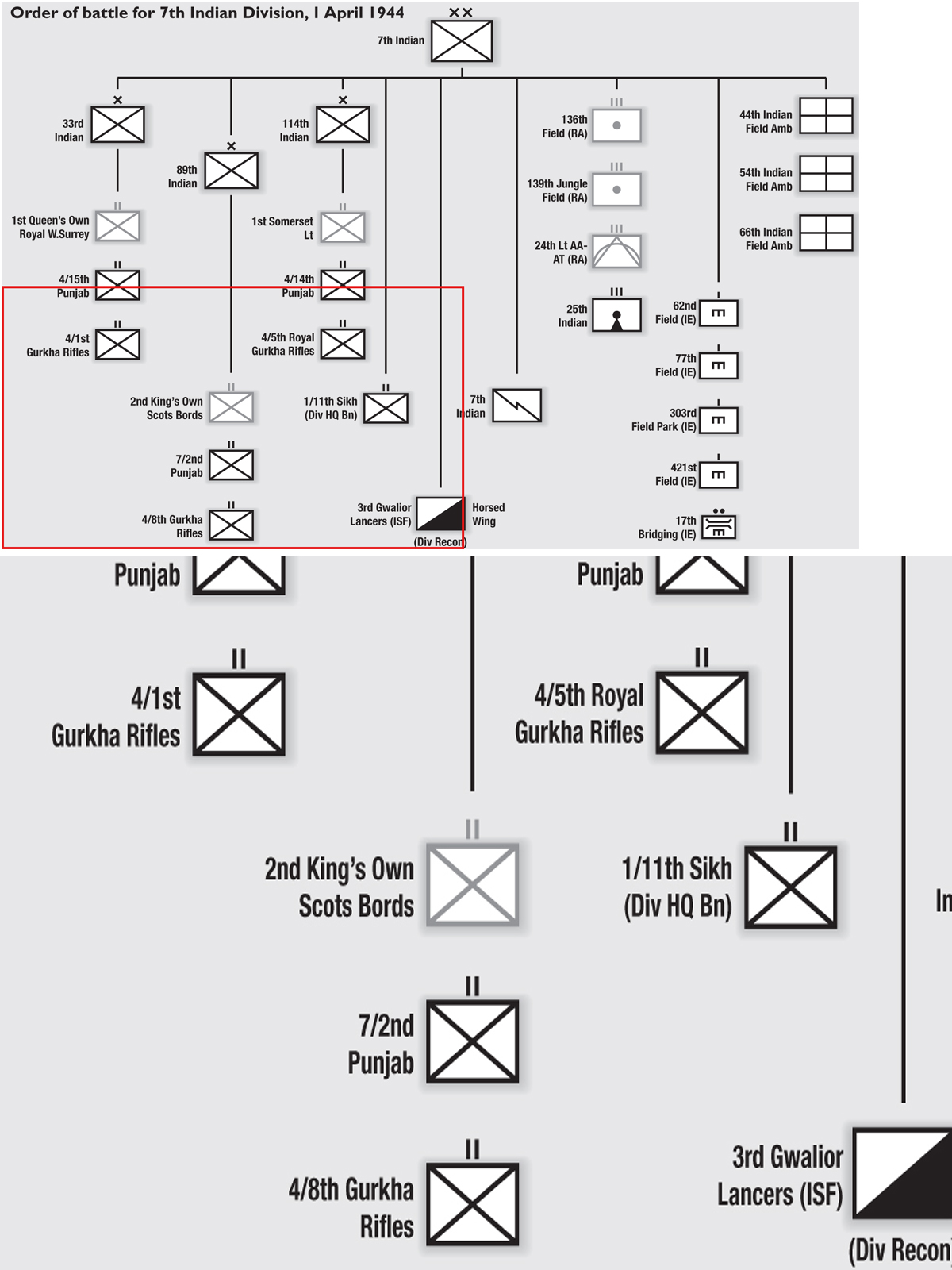

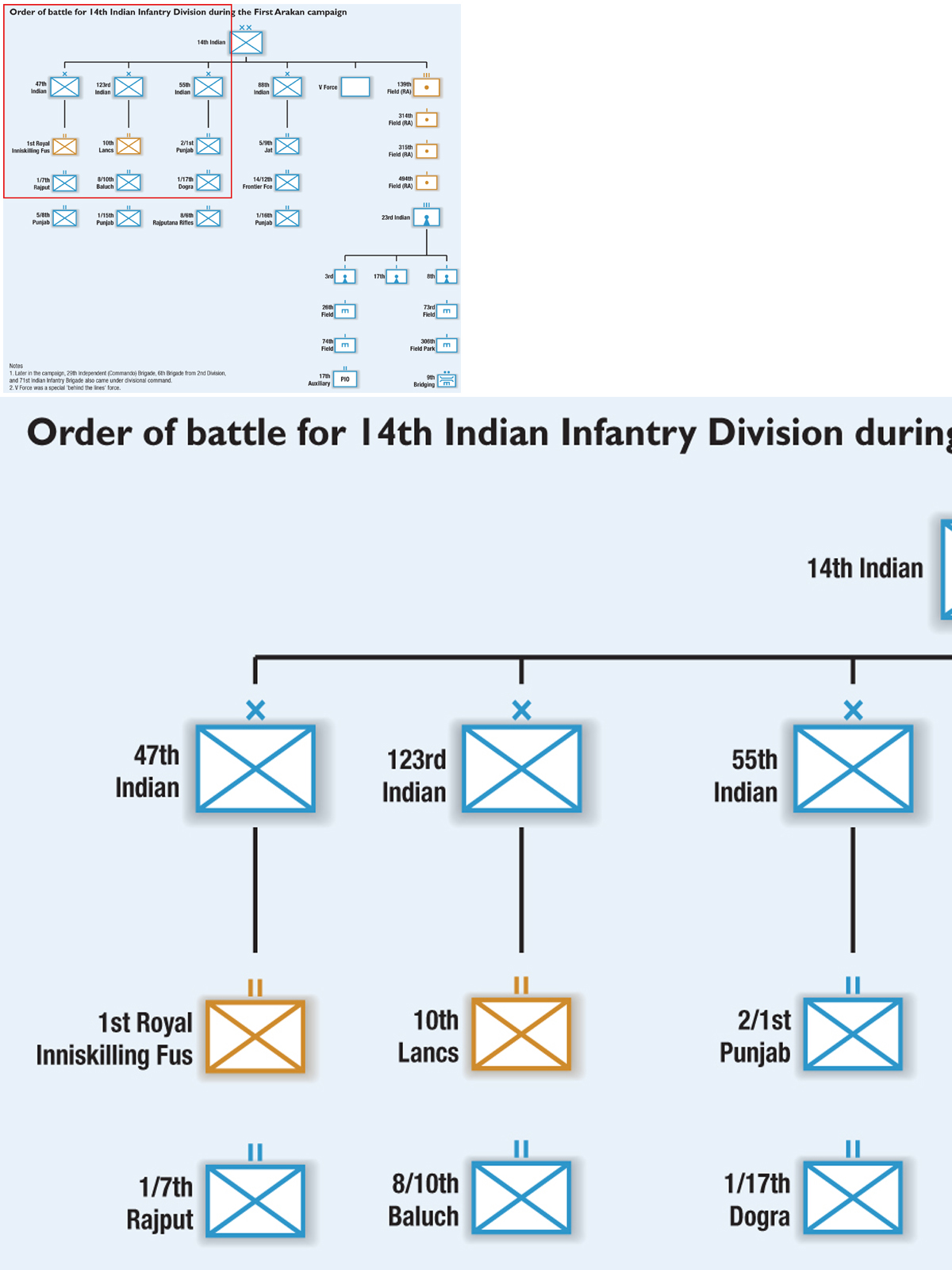

In the Commonwealth armies during World War II, apart from Higher Commands, the structure started with an army-level unit. In this particular theatre, from 1943 onwards it was the 14th Army. In an army there are usually two or three corps and three divisions within a corps. An army division was composed of three brigades of three battalions, one of which would be a British Army battalion in an Indian Army division.

14th Army’s formation badge. It was designed by Slim himself, but was only adopted after an open competition. The red and black represented the colours of the British and Indian armies and the sword pointed downwards, against heraldic convention, because Slim knew that the 14th Army would have to re-conquer Burma from the north. The hilt formed the ‘S’ for Slim and on the handle was the army’s title in morse code.

All the divisions bar one that fought in this theatre were infantry divisions. There were three British divisions in theatre, namely the regular British Army 2nd Division, 18th Division and the 36th Division. There were also two West African divisions and the 11th East African Division, all led by British officers and NCOs. One Australian division fought in Malaya and two Canadian regiments in Hong Kong. The majority of the Commonwealth troops were provided by the Indian Army, which contributed 13 infantry divisions and one airborne division in South-East Asia. As Major-General Henry ‘Taffy’ Davies, Commander of 25th Indian Division, commented in his memoir:

The Division, as all soldiers know, is the basic fighting formation in practically every army in the world. It is large and powerful enough with its establishment of about 17,000 men, to effect a decisive influence in any military operation, irrespective of the scale of campaign. At the same time, it is sufficiently compact to enable its commander to exercise a personal leadership and control and to permit its functioning as a well co-ordinated team. In the British Army, during two world wars, the Divisional spirit has been something which has been fostered and nourished as an important matter of principle.6

However, in the Far East as elsewhere, the fundamental loyalty of the soldier was to his immediate peer group and typically to his own infantry section.

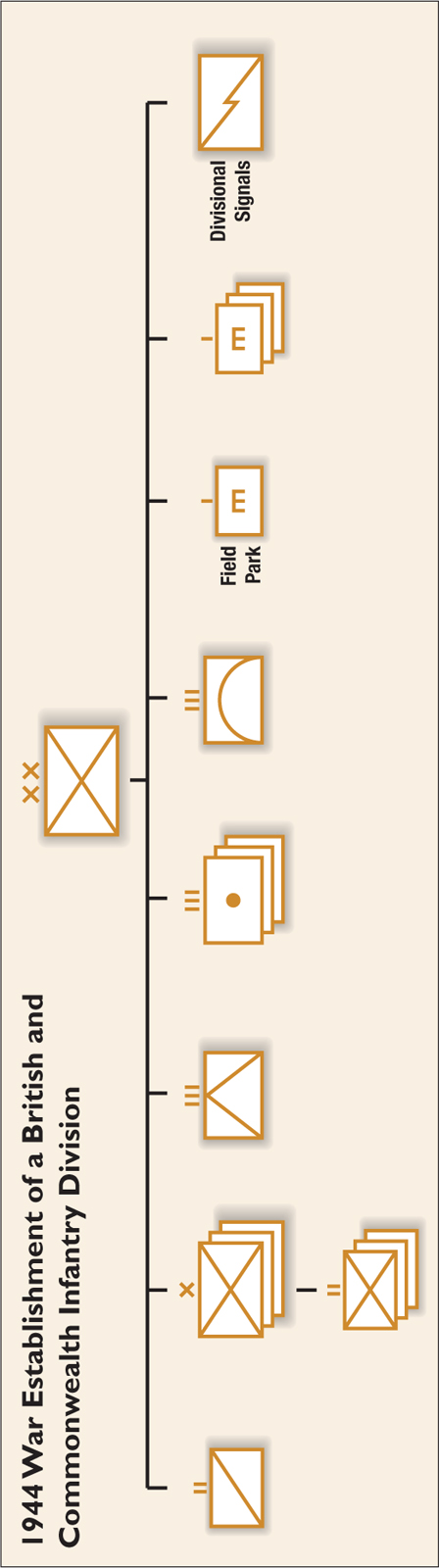

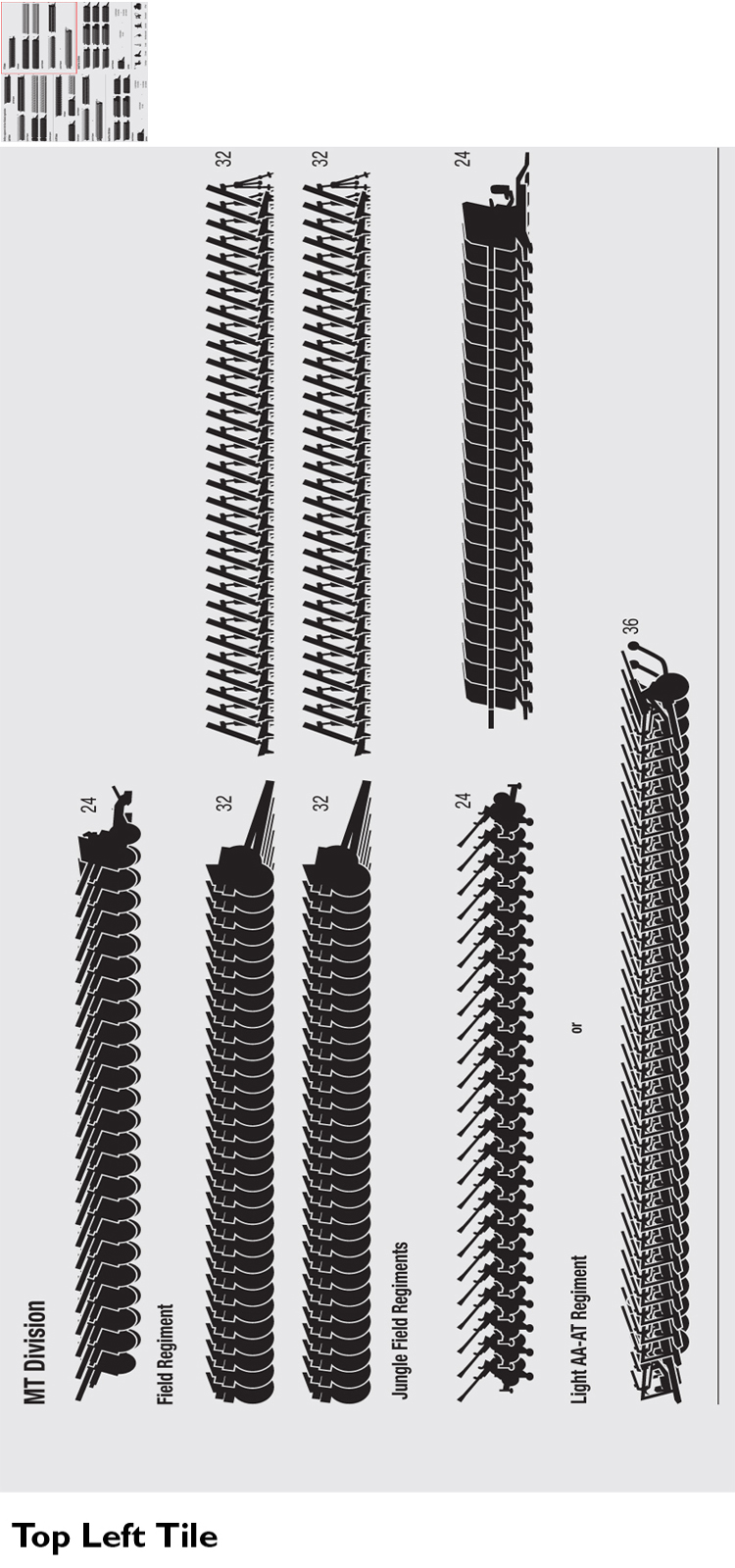

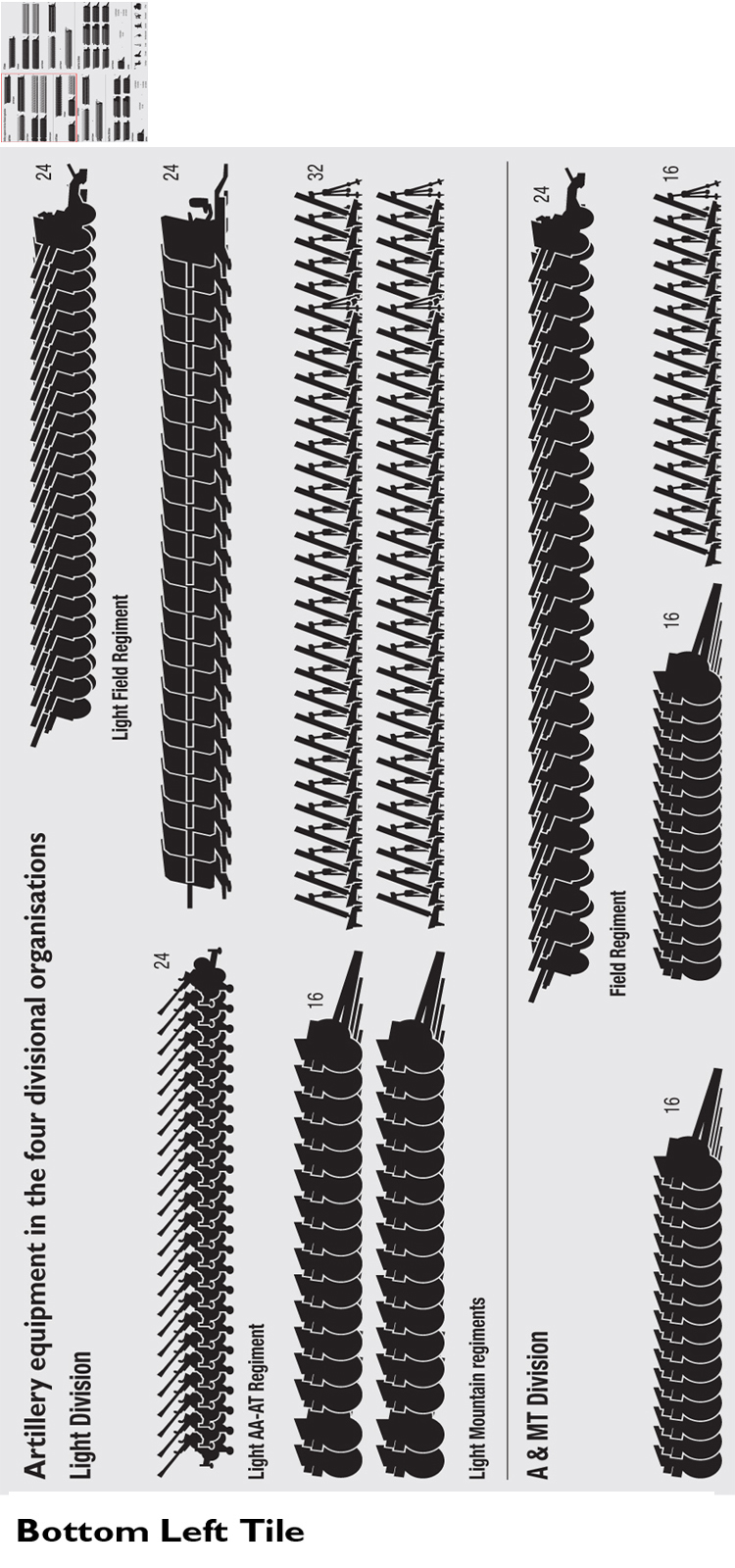

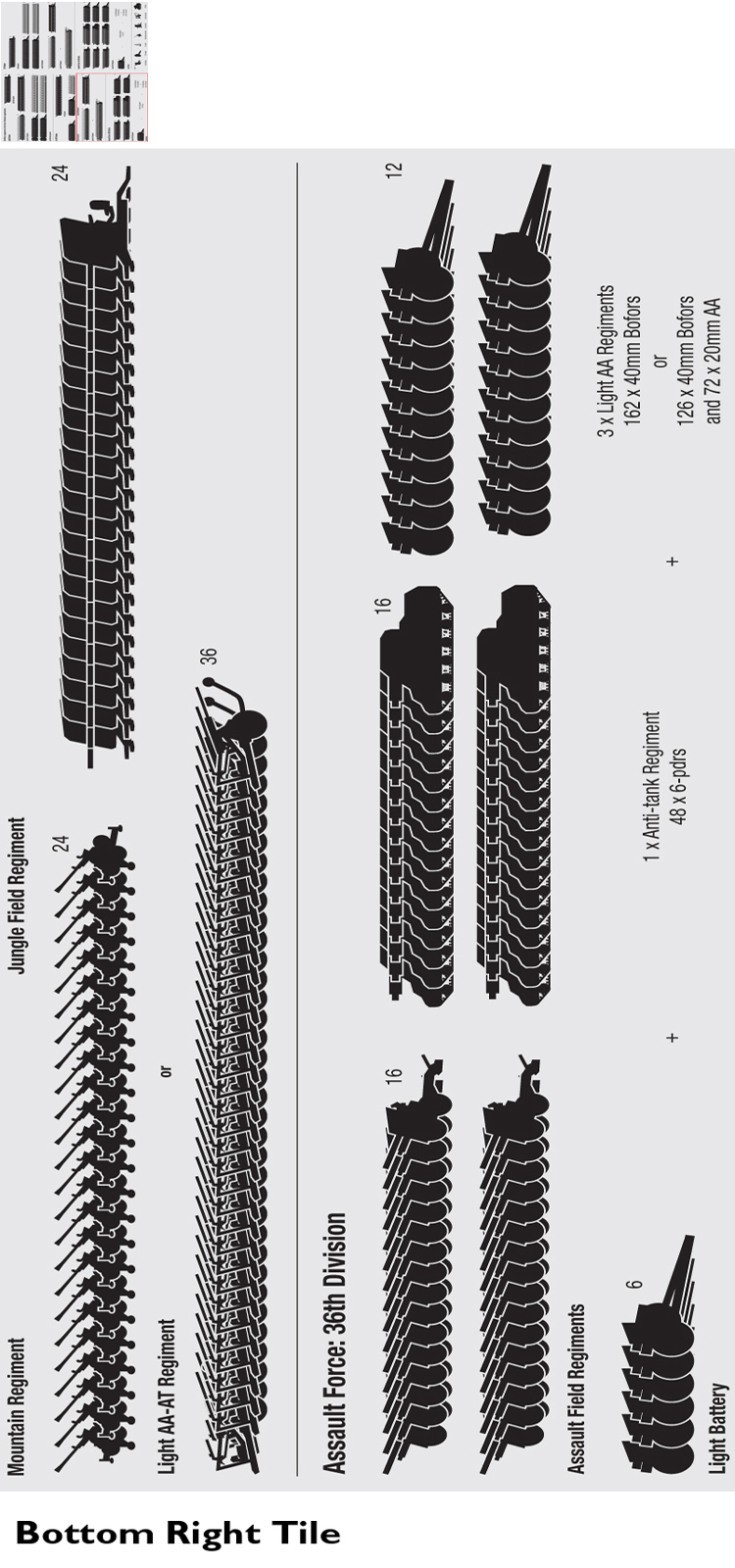

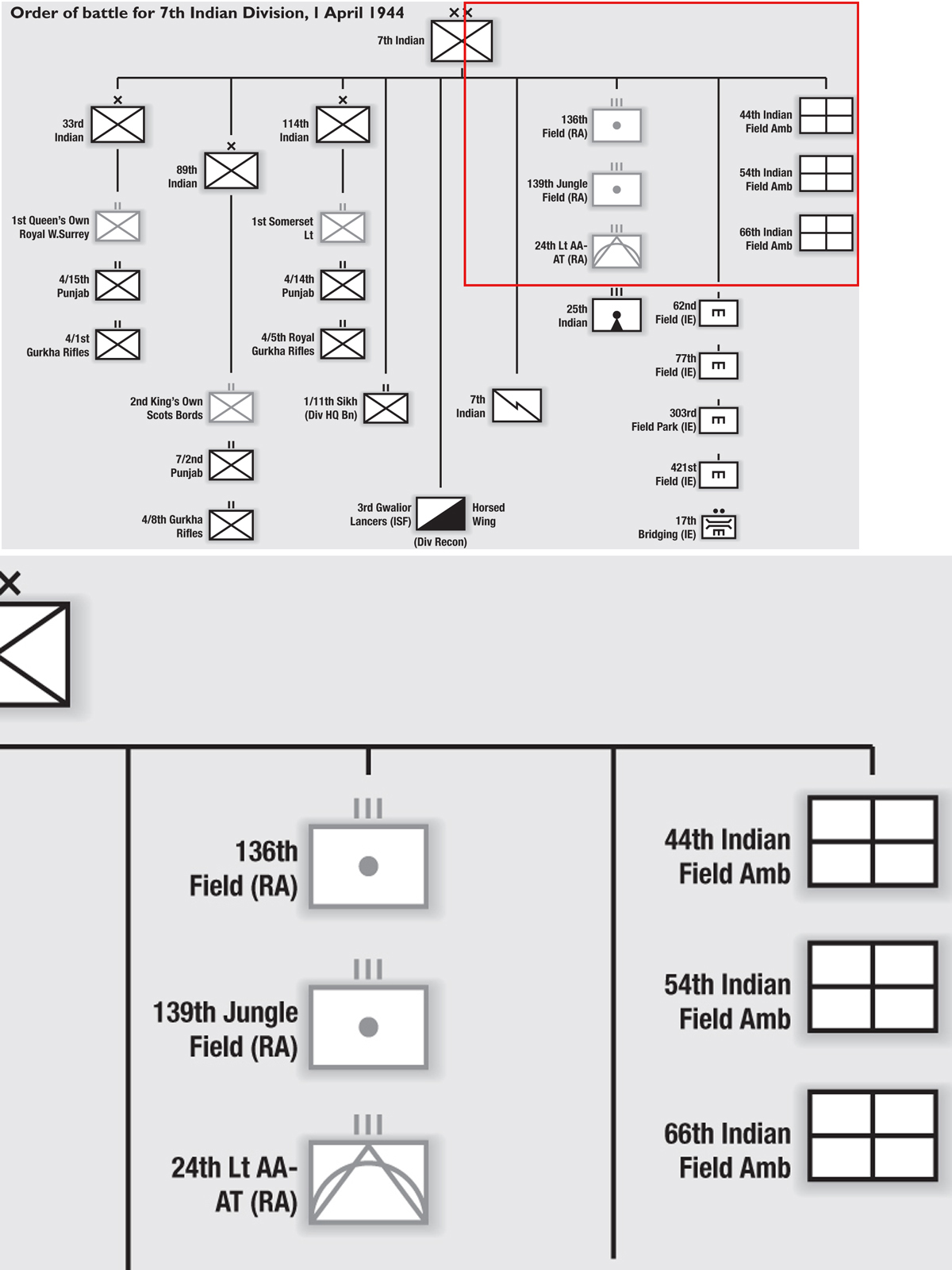

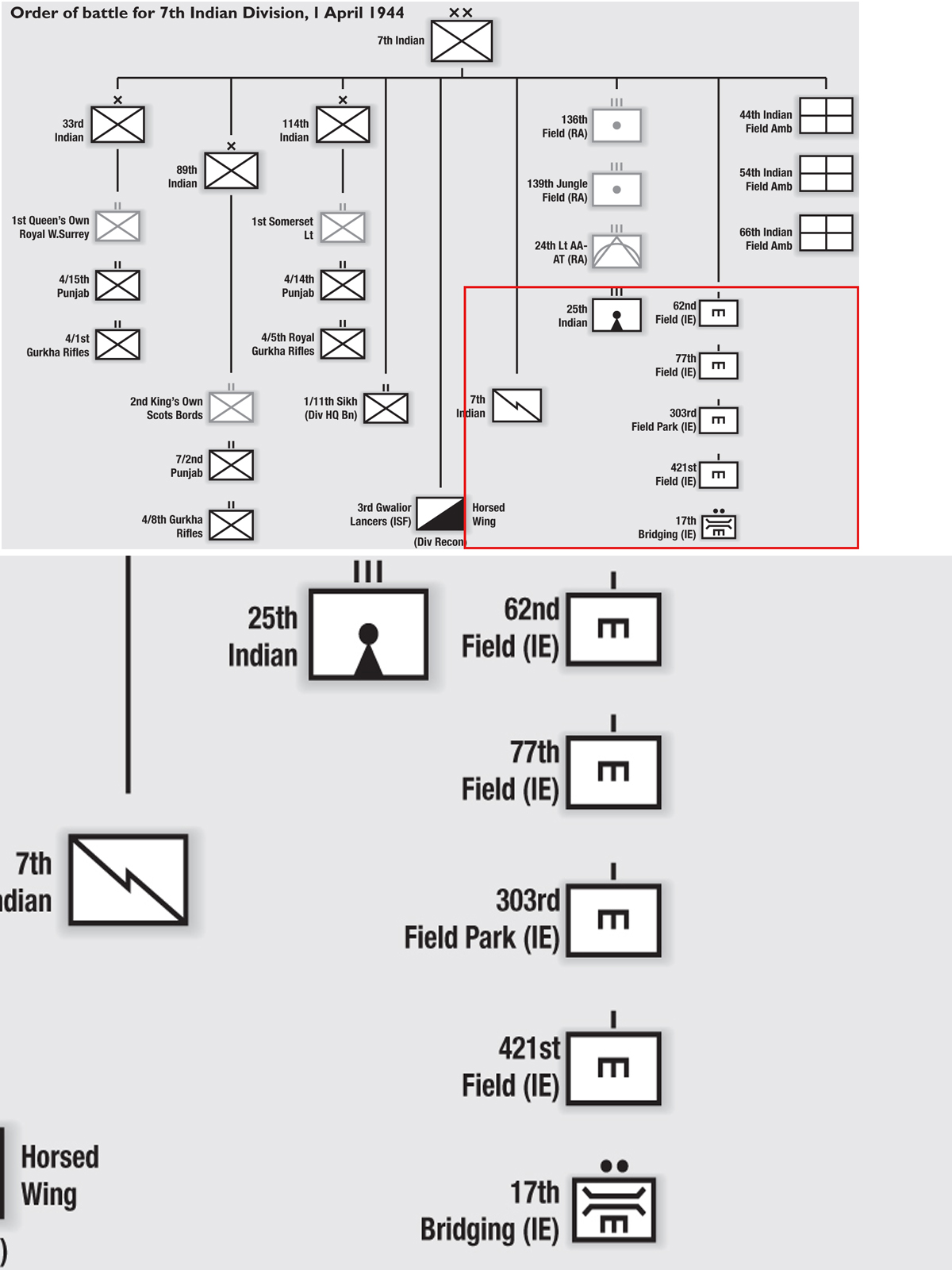

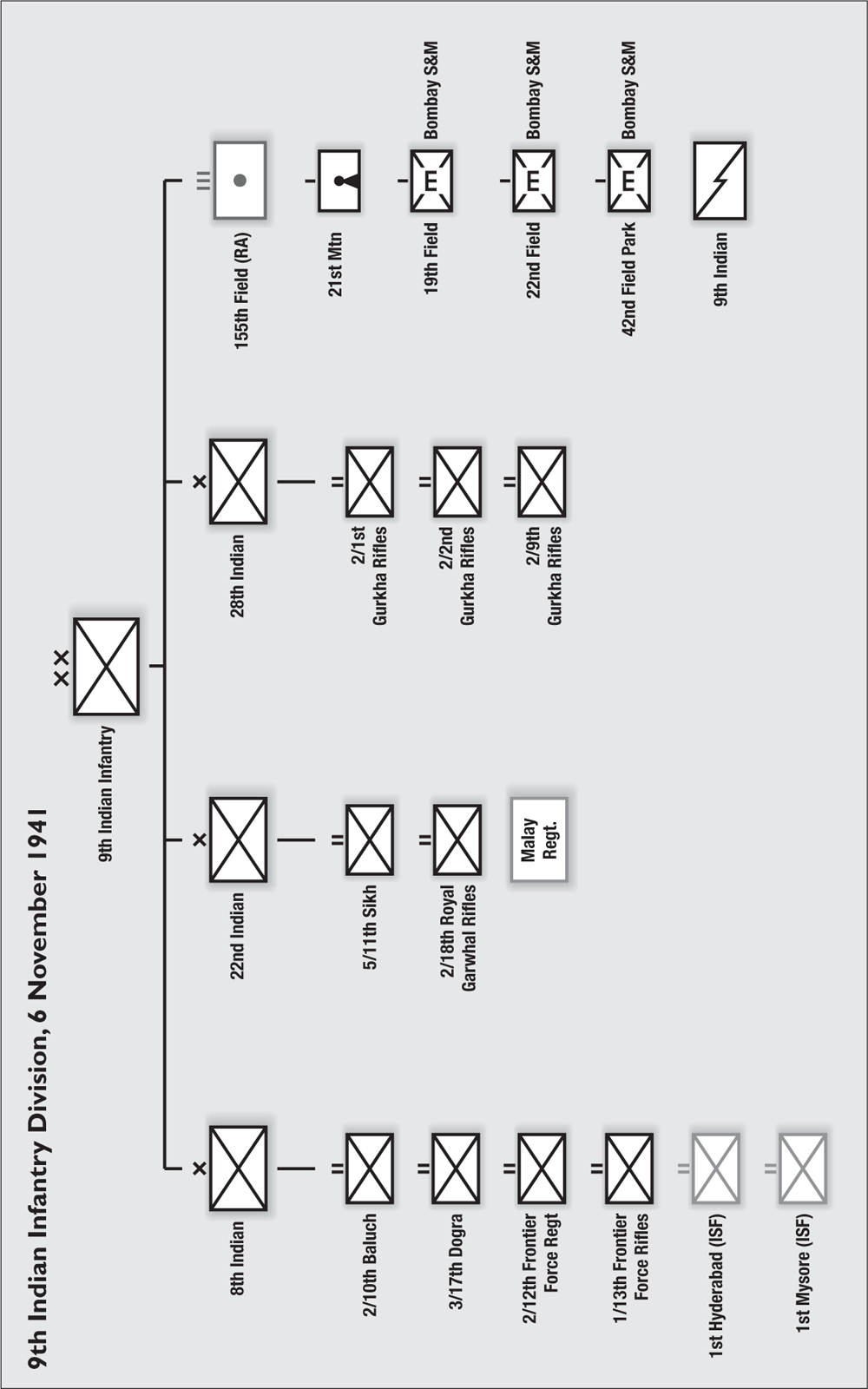

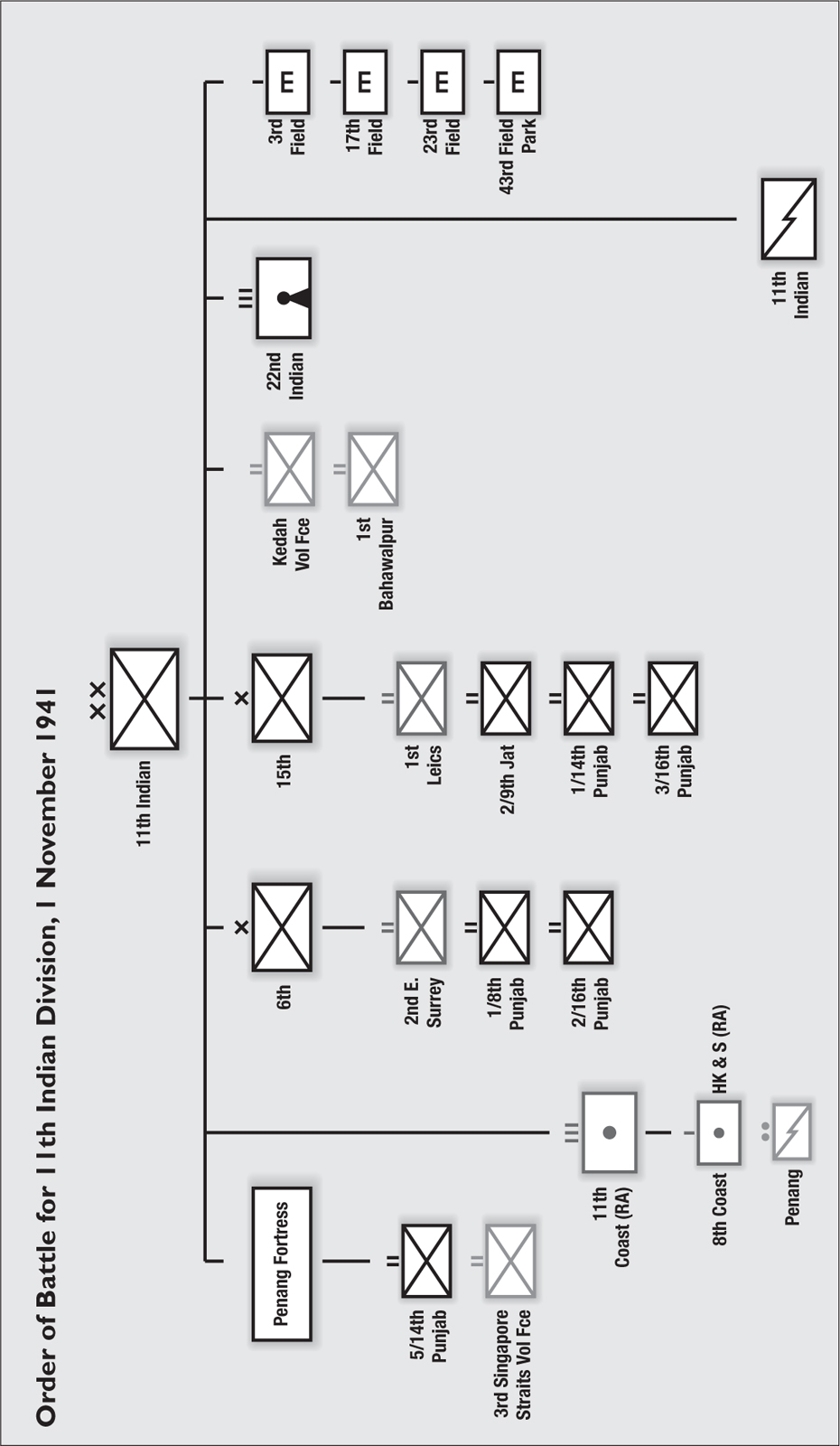

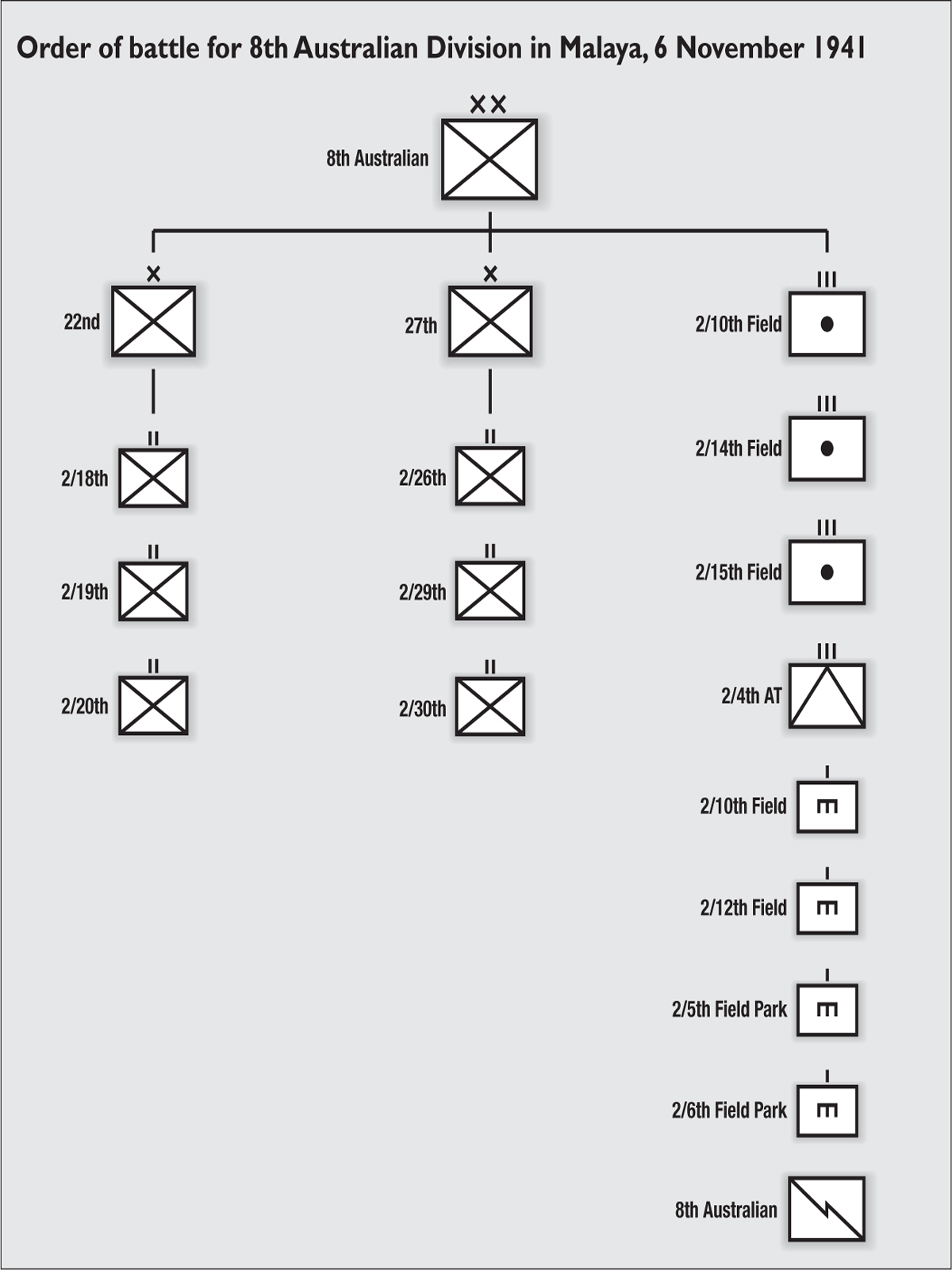

In 1941, the war establishment of British and Commonwealth Army infantry divisions usually consisted of three infantry brigades of three infantry battalions plus three artillery field regiments, one anti-tank regiment, one light anti-aircraft regiment, three engineer field companies, one field park company and divisional signals. This developed throughout the war according to the theatre the division was fighting in. The Indian Army prior to World War II had largely been organised for the roles of imperial policing on the North-West Frontier and internal security. Therefore, even with its expansion and the resultant ‘milking’ of existing units, it was in need of reorganisation to fight the IJA. The highest formation in India in 1939 was a brigade.

Each standard infantry battalion normally had four rifle companies as well as a support weapons. Each company, in turn, was split into three platoons and each platoon into three sections of about ten men or less, but usually more than six. Even within the section a soldier usually had a ‘mucker’ or mate with whom he ‘brewed up’, the pair looking after each other in and out of action. This was the usual foundation for comradeship among all soldiers and kept individuals going through the tremendous hardships of fighting the Japanese and the jungle. This is well depicted in George MacDonald Fraser’s Quartered Safe Out Here, and highlighted by the 2nd and 36th Divisions’ historian:

In Burma, more than in any other theatre, it was an infantryman’s war, and it was the section, the platoon and the company that won the many small victories which, added together, made the campaigns the successes they were.7

In the 14th Army as a whole, no matter whether the troops were African, British or Indian, there was a belief that the soldiers were fighting a worthy cause not merely to defend India and reoccupy Burma, but to defeat the Imperial Japanese Army as an ‘evil force’. Loyalty to the 14th Army and the individual British, Indian and African divisions was fostered through the use of formation badges, training and going into action together.

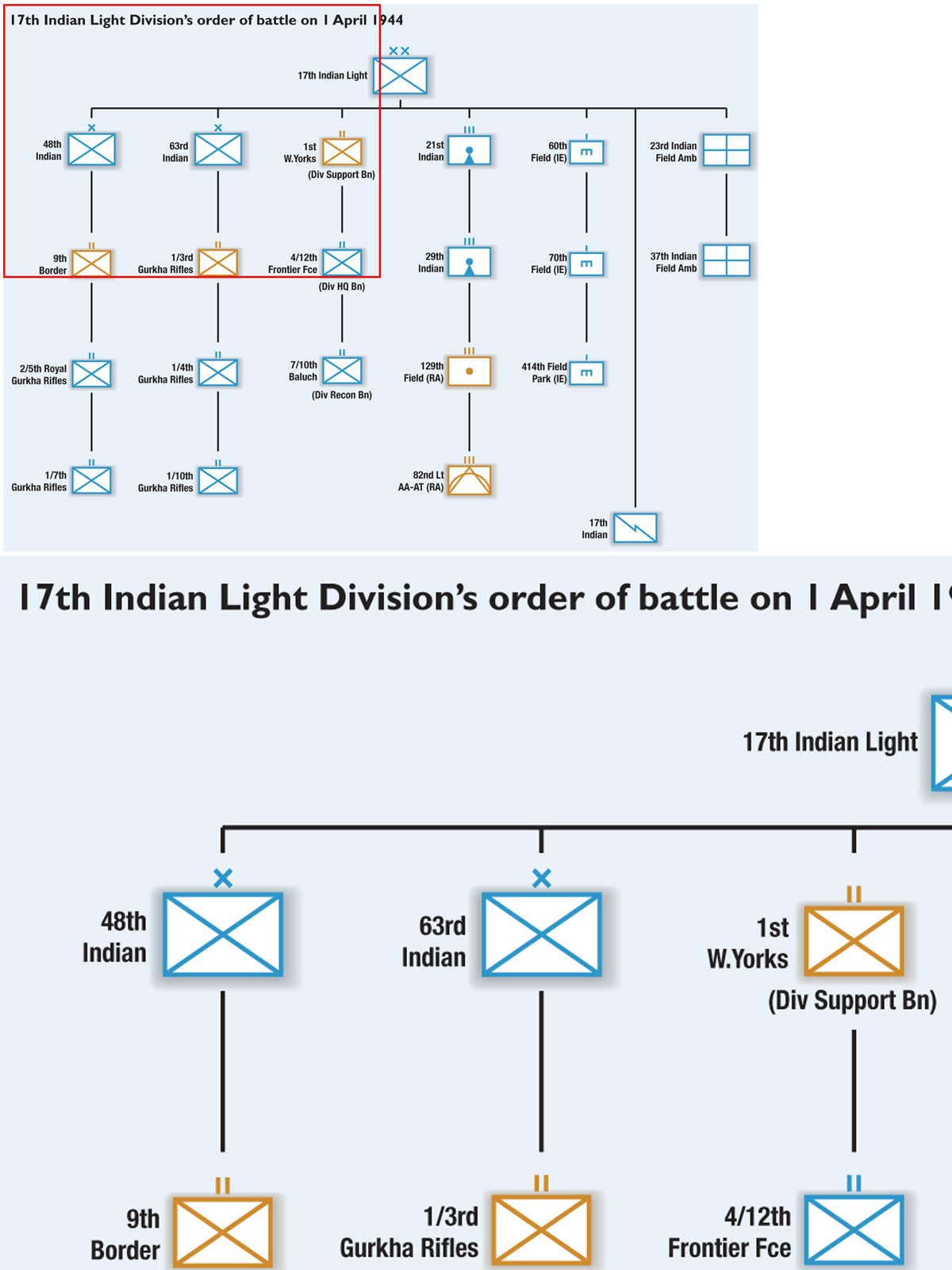

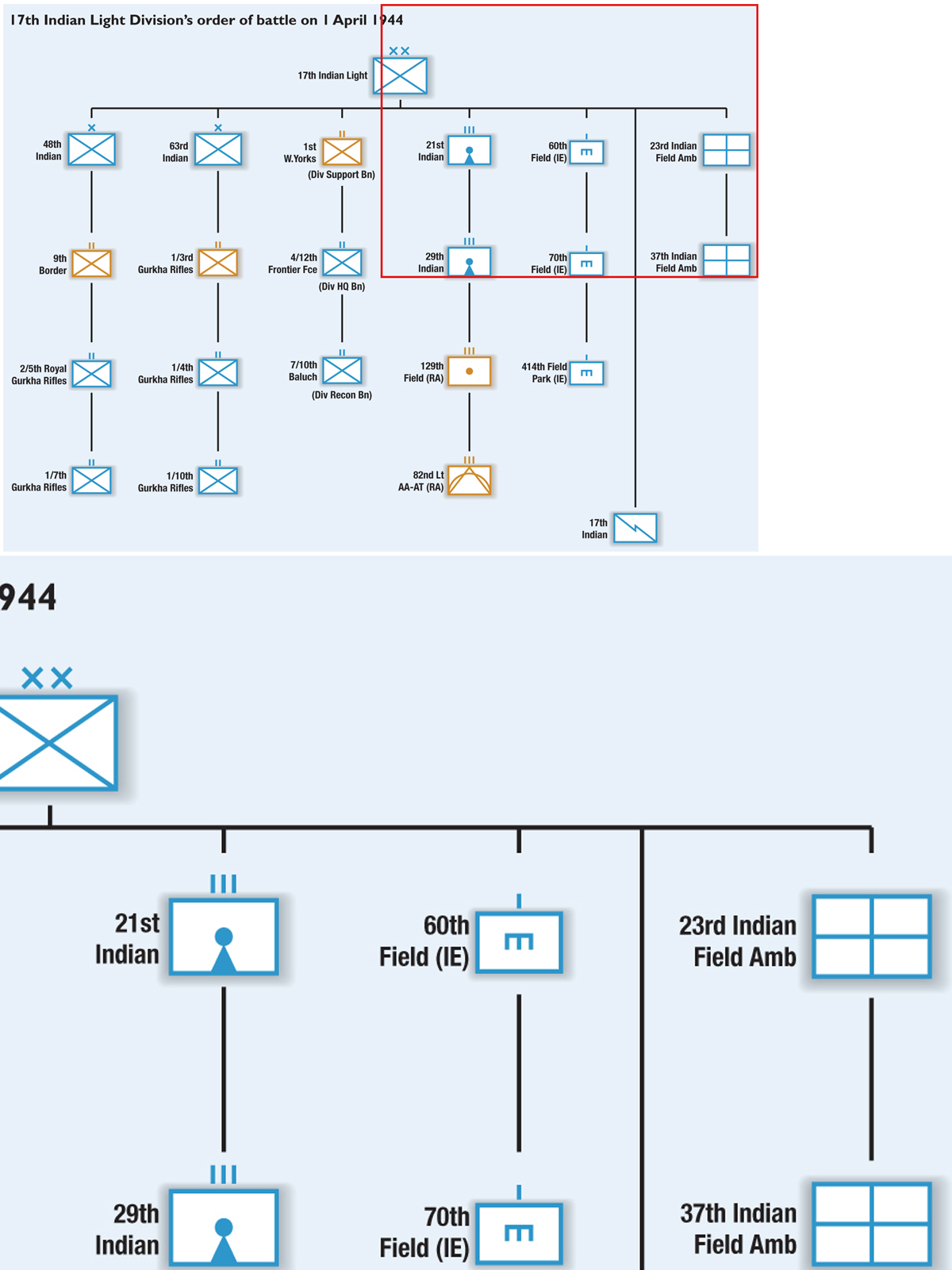

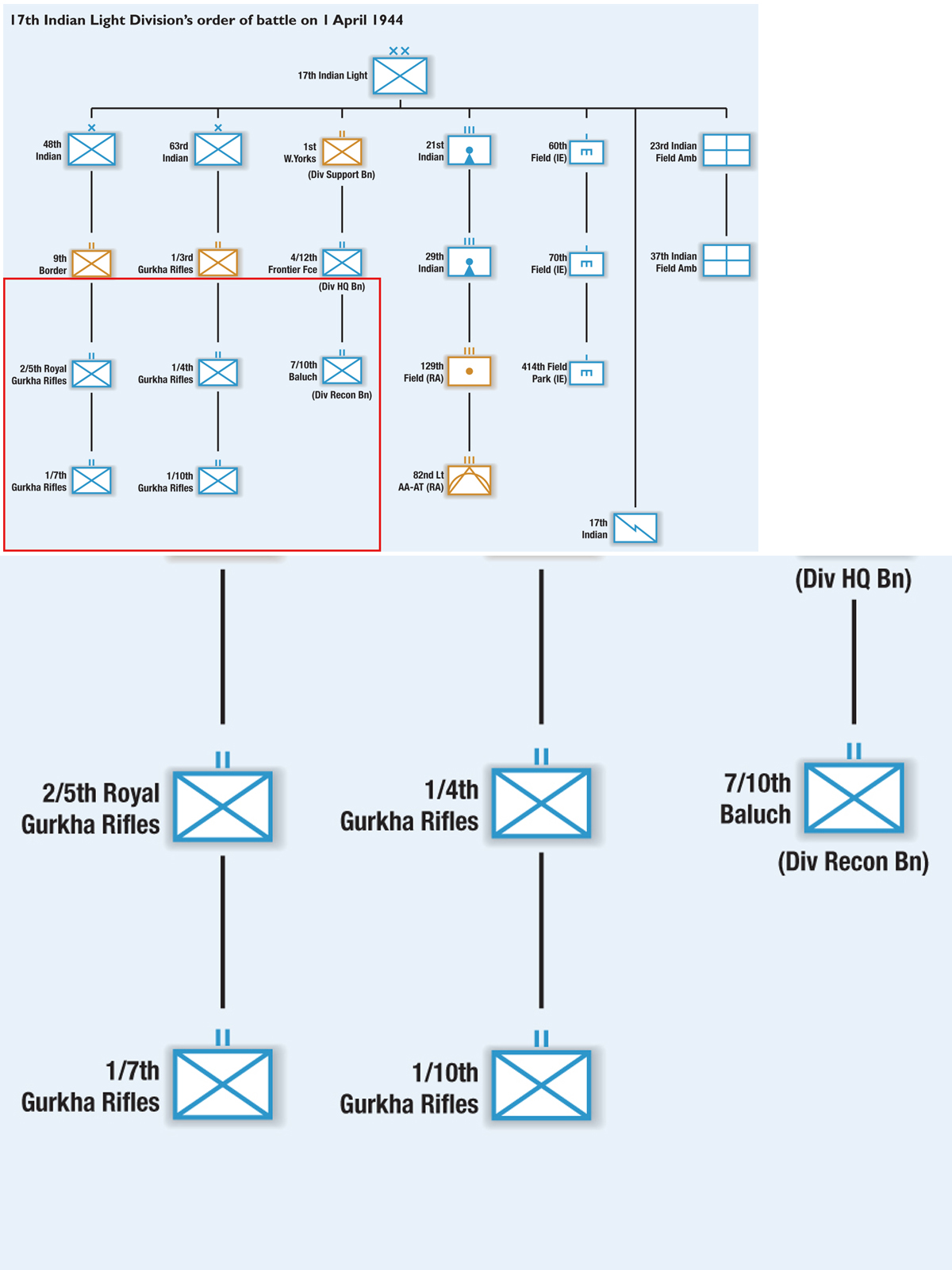

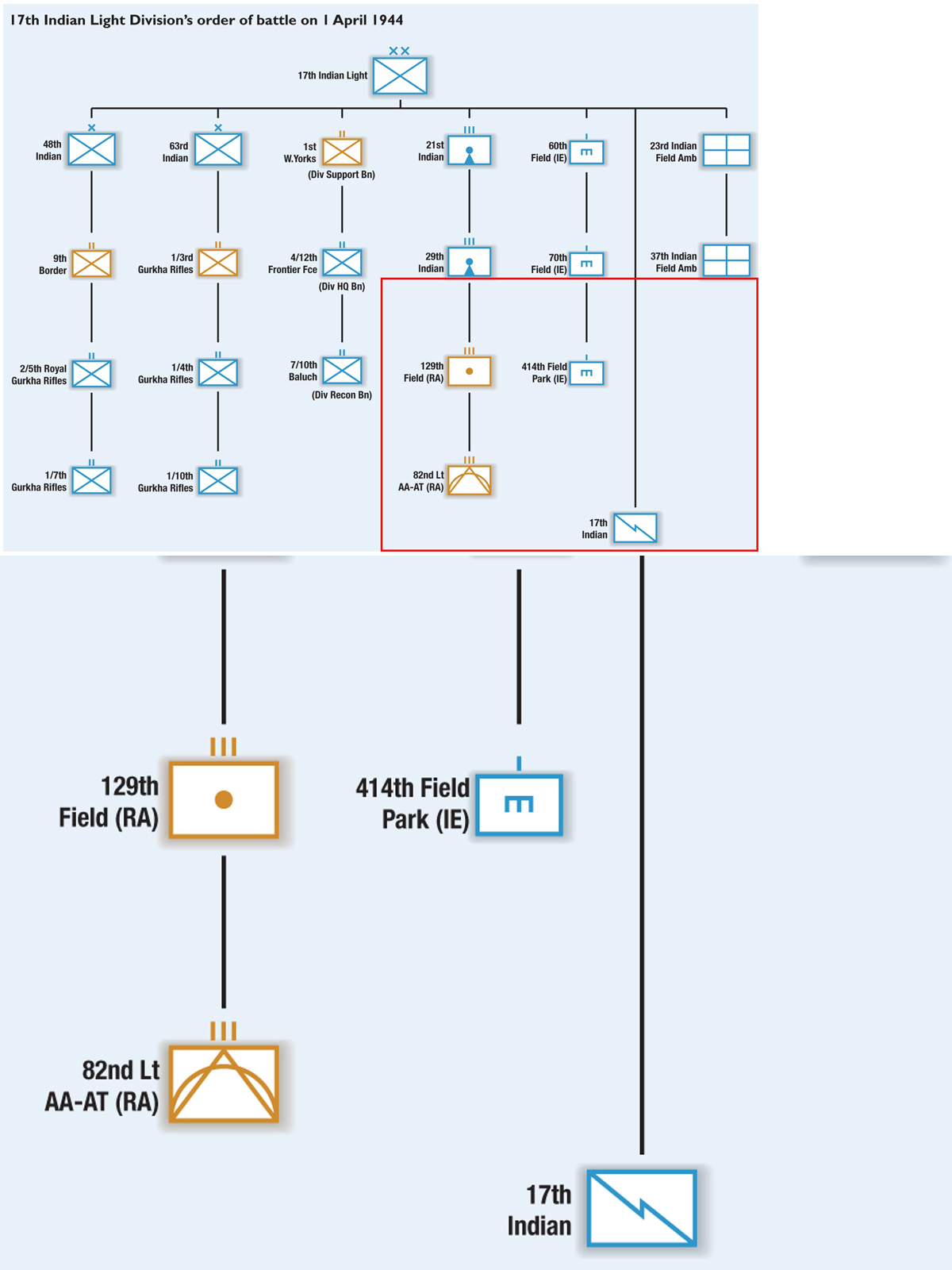

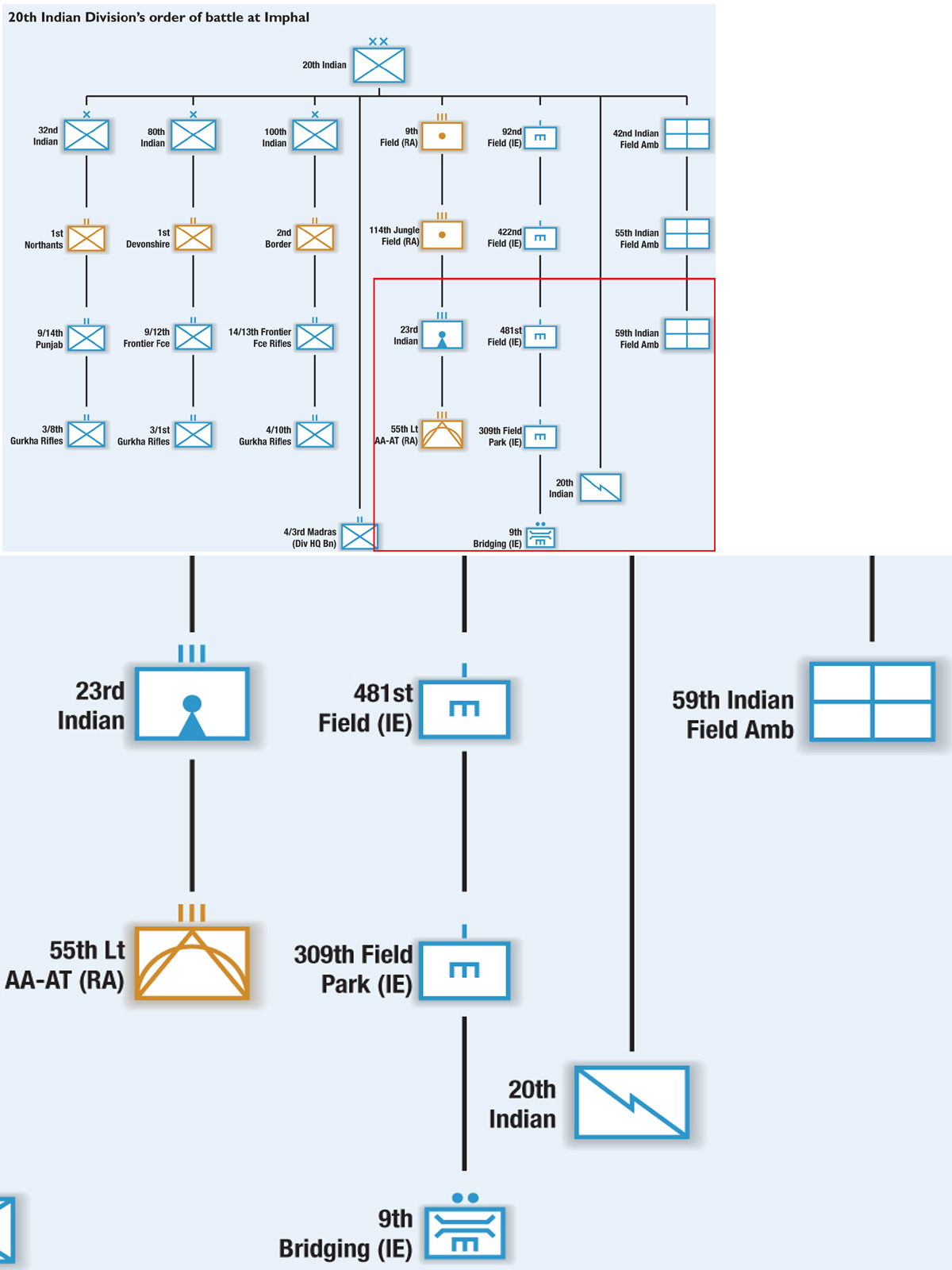

After the 1942 retreat from Burma, reorganisation within the divisional structure was instigated in response to the over-reliance on roads in the recent campaigns. The number of vehicles was reduced in the 7th, 20th and 23rd Indian divisions, which were renamed Mixed Transport divisions and later called Animal and Mechanised Transport divisions (A & MT) rather than MT divisions. The 17th and 39th Indian divisions were converted to Light divisions of two brigades, with six mule companies and four jeep companies each, in order to be able to operate away from the road. Other changes in the Light Divisions included abolishing the anti-aircraft and gun platoons in the British units. The gun platoon was replaced by a medium machine-gun platoon.

The lessons of the First Arakan also brought about changes in organisation of divisions fighting in the jungle. These included the formation of one artillery regiment in each division specifically as a jungle field regiment. Two batteries were equipped with eight jeep-towed 3.7in. howitzers (modified with pneumatic-tyre wheels for towing) and the third battery with sixteen 3in. mortars to give artillery support where 25-pdr field artillery guns could not be used. Thus, the jungle field regiment could operate away from the roads, and mountain regiments would operate where jeeps could not be used. Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tanks regiments were also combined for fighting in the jungle to make one Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment with two batteries each of twelve 6-pdrs and the other two batteries each of eighteen 20mm anti-aircraft guns. In the MT and A & MT divisions, British and Indian battalions were reorganised to consist of battalion HQ, HQ company containing signals, mortar, carrier and pioneer platoons, an administrative company containing medical and transport platoons and four rifle companies.

In 1944 there were four distinct divisional organisations in India: the MT Division, the A & MT Division, the Light Division and the Assault Division. This was standardised in a conference at GHQ India on 26–27 May 1944, during the Battle of Imphal, and was also influenced by the recommendations of the Lethbridge Mission of June 1943 (see the Weapons and equipment chapter). All divisions were now required to have a divisional HQ defence battalion. The Lethbridge report recommended that this did not have to be a permanent arrangement and the battalion could be exchanged at intervals with a battalion from one of the infantry brigades. It also recommended that each division have a reconnaissance battalion of Light Infantry that would be of similar organisation to an infantry battalion bar the medium machine gun and 3in. mortar platoons, with an increase in the signals platoon and the dropping of one company. The battalion would, therefore, have a battalion HQ, a HQ company consisting of company HQ, signal platoon, transport platoon, administrative platoon and a pioneer platoon, with three rifle companies with company HQ and four platoons. This would enable the reconnaissance battalion to be extremely mobile and to work independently of the parent unit for long periods at a time.

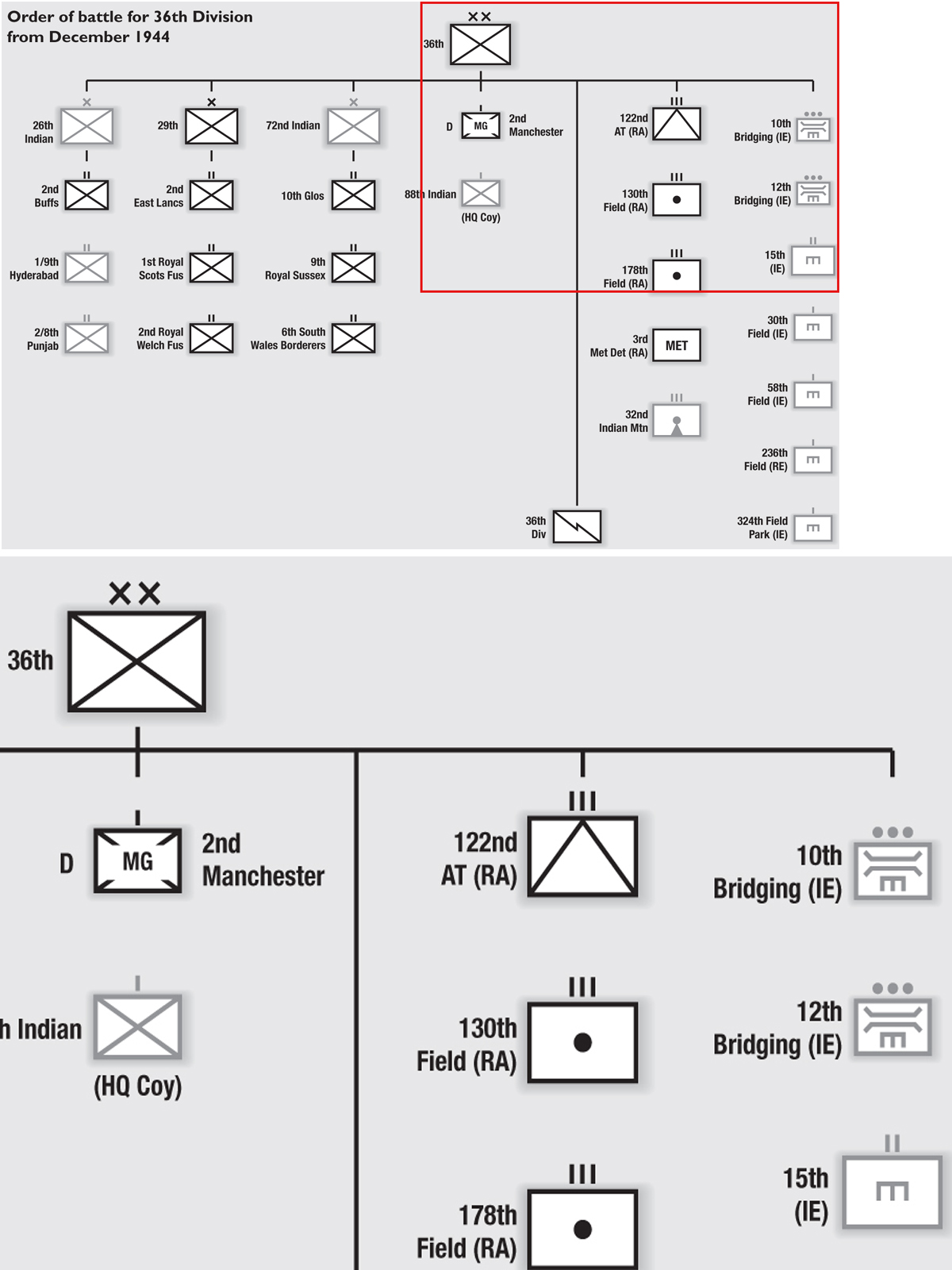

In addition, each division was allocated a medium machine-gun battalion, as a result of the experiences of the 2nd Battalion, the Manchester Regiment acting in this role for 2nd Division. Artillery was again reorganised as the presence of 25-pdrs was seen as essential; divisional artillery now comprised two field regiments of three batteries of 25-pdrs and one mountain regiment of three batteries of 3.7in. howitzers. The renewed use of anti-tank weapons in the Far East for bunker-busting meant that an anti-tank regiment of three batteries of 6-pdrs was reinstalled in the divisional set up. An Indian Army battalion in an infantry division in 1944 would comprise 866 men with A & MT of 12 jeeps and 52 mules, led by the troops of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps rather than infantry. This all meant that the new standardised division could now cover all the roles of the four previous, differently organised divisional structures.

The following section lists the combat records and organisational structures of the most important infantry divisions that fought in theatre. Space precludes a detailed treatment of every type of unit that served, and so a selection has been made of those that merit most attention.

The 2nd Division was reformed after Dunkirk and made responsible for home defence on the Yorkshire coast. It then underwent training in late 1941 and embarked for the East in April 1942. The new commander was Major-General J.M.L. Grover. On arrival in India, the division undertook more training mainly at Ahmednagar, with some jungle warfare training at Belgaum and Combined Operations training near Bombay.

The British 2nd Division’s formation badge. This badge was chosen in 1940 by the then GOC, Major-General H. Charles Lloyd. It is said to derive from the arms of the Archbishop of York and to be a reference to the time when Britain used to raise two armies, one being from the north. 2nd Division was a regular division at the outbreak of World War II and it formed part of the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium in 1940. It was transferred to India in June 1942 and went into action in Burma as part

6th Infantry Brigade and the 1st Battalion Royal Scots took part in the First Arakan offensive. Originally the brigade was meant to take part in the amphibious landings on Akyab Island, but when this was called off the brigade was brought in to aid numerous attacks on Donbaik. The brigade found itself the target of the Japanese counter-attack. However, lessons were learnt from the disastrous First Arakan, the first experience of jungle warfare for the British troops.

Major-General Frank Festing, Commander of 36th Division, is shown here driving his personal Willys MB on the road to Mawlu in November 1944. He led the advance into Mawlu when the leading platoon lieutenant was killed. He was nicknamed ‘Front Line Frankie’ because he believed in leading his troops from the front. Festing was educated at Winchester and joined the Rifle Brigade in 1921. He served as ADC to Major-General Sir John Burnett-Stuart, passed through Staff College in 1936 and was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel. Instructor at the Staff College in 1939. During World War II, he served as liaison officer to General Sir Bernard Paget in the raid on Trondheim in the Norwegian campaign. He was then given command of 2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment and then command of 29th Brigade in October 1941. He led the brigade in Madagascar, capturing Diegon-Suarez, Majunga and Tamatove. He was promoted to major-general at the end of 1942 and given command of 36th Division. After World War II, Festing was appointed GOC Hong Kong and then posted back to London in 1946 as Director of Weapons and Development. In 1951 he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff at SHAPE (Supreme Allied Powers in Europe) HQ. From 1952 to 1954 he was GOC British Troops in Egypt, then GOC Eastern Command, and in 1956 C-in-C FARELF (Far East Land Forces). He ended his army career as CIGS from 1958–61. (Photo: IWM SE 2524)

The whole 2nd Division was engaged at Kohima, crossing India and immediately entering action. The Kohima Garrison and 161st Indian Infantry Brigade were relieved by 2nd Division and went on to retake the surrounding areas: 4th Brigade advanced to the west of Kohima, 5th Brigade to the east, and 6th took the centre along with 161st and 33rd Indian Infantry brigades. By 16 May, Kohima had been recovered. This fitting epitaph was bestowed on the division for its role in the fighting there:

When you go home

Tell them of us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

On 22 June, the 2nd Battalion, Durham Light Infantry together with A Squadron, 149 Regiment Royal Armoured Corps broke through the Japanese positions on the Kohima–Imphal road to join up with a company of 1/7th Dogras of 5th Indian Division. In July 1944 Major-General C.G.G. Nicholson took over command of the division, and after Kohima most of the division rested and retrained with the reinforcements. 4th Brigade continued to search out Japanese resistance at Ukhrul, and 5th Brigade with 23rd Indian Division pushed back Japanese forces into Burma and captured the village of Tamu.

The division was back in action in the fight from the Chindwin to Shwebo, which took 20 days. It then participated in the capture of Mandalay, by cutting off the escape routes for the fleeing Japanese. After the city had been captured, the division continued mopping up operations. The division was to be used in the capture of Rangoon but was not needed in the end. Indeed a large number of divisional personnel were eligible for home leave, having done the necessary three years and four months service under the Python scheme. The division was later earmarked for Operation Zipper, the recapture of Singapore.

18th Division arrived in Singapore in January 1942. It was originally destined for the Middle East but had been diverted to India, before being redirected to Singapore on Churchill’s orders. The division had spent two months crossing the Atlantic and the Pacific before arriving in Singapore. It had been equipped for desert warfare and went straight into action with no training or chance to acclimatise. On 13 January a convoy arrived at Singapore carrying 53rd Brigade of 18th Division, along with anti-aircraft, anti-tank units and 51 crated Hurricanes. 53rd Brigade were immediately sent to Johore, where the Brigade took over 500 casualties and lost much of its equipment. They were able to re-equip but only at the expense of the newly arrived 54th and 55th brigades, and the Division’s headquarters under Major-General M.B. Beckwith-Smith, who very briefly fought on Singapore Island. Most of the division spent the next four years in captivity.

The formation badge of 18th Division. The windmill is a reference to the region of East Anglia, England, where the division

36th Division’s formation badge. The badge was an amalgamation of the two individual brigade badges: the white circle for the 29th, after its first Commander General Oliver Leese, and the red for the 72nd.

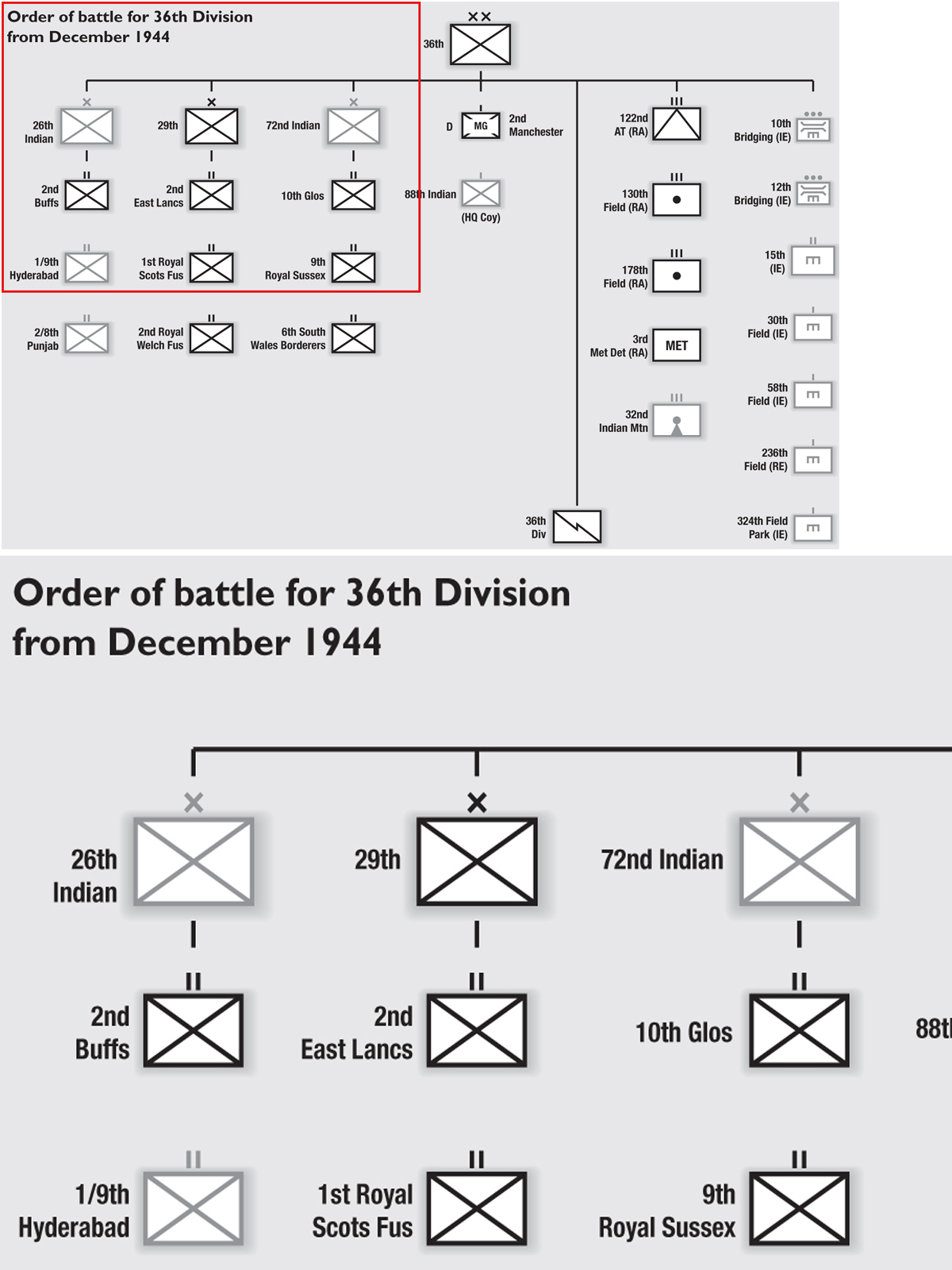

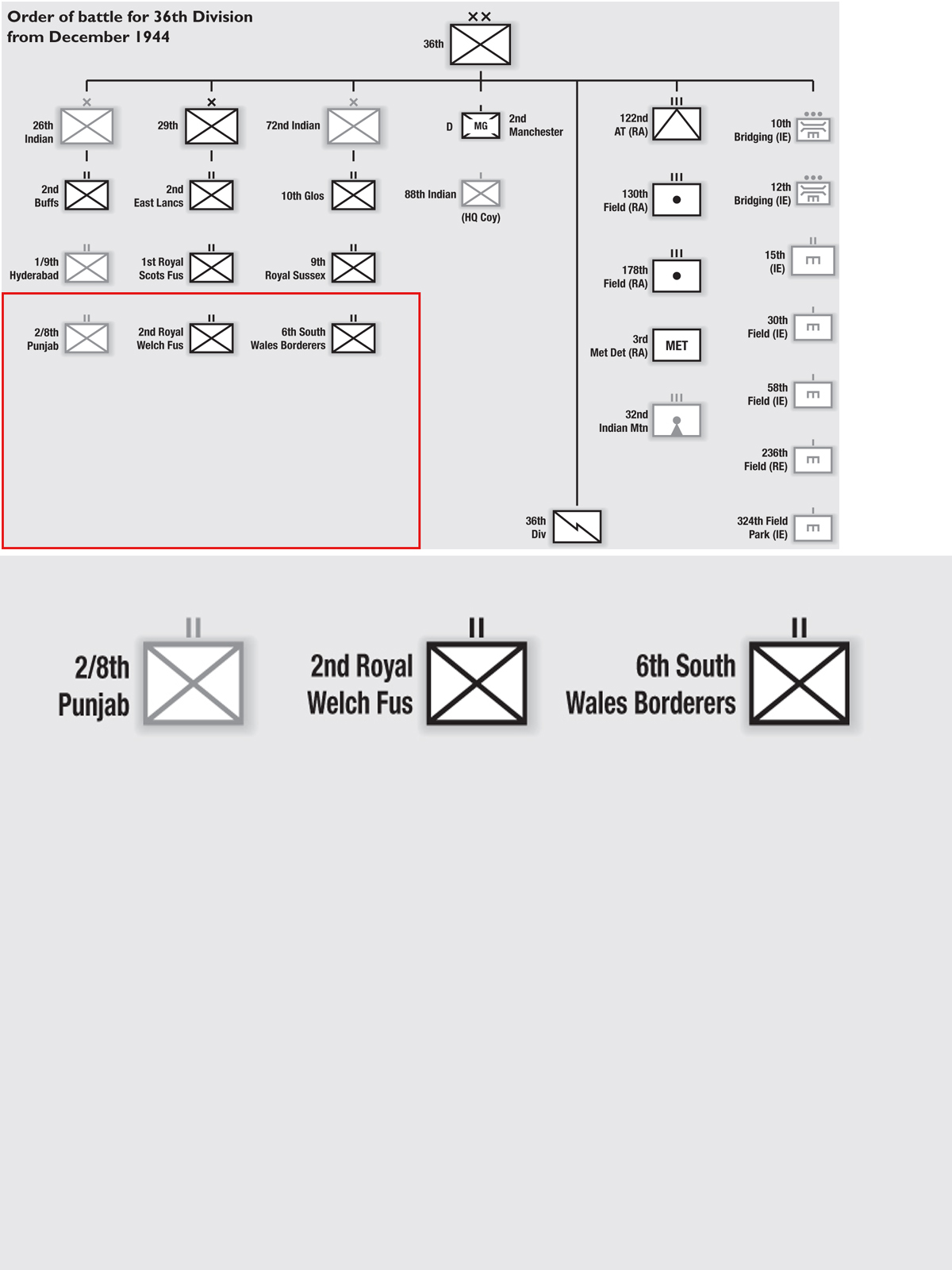

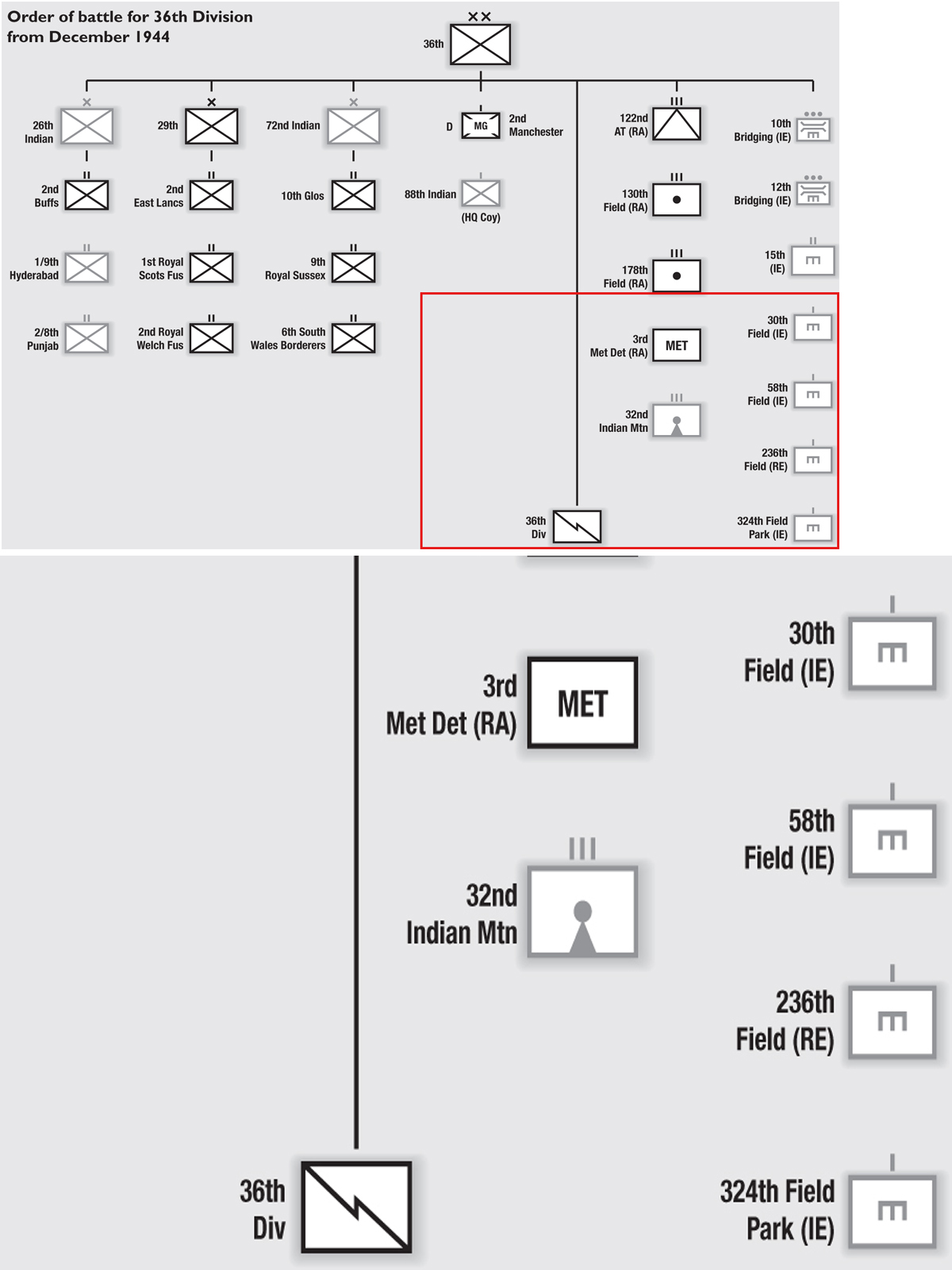

The 36th Division was raised from June 1942 as an Indian Army formation, consisting of 29th British Brigade and 72nd Indian Infantry Brigade. 29th Independent Brigade had been formed in June 1940. In 1941 Brigadier Festing took over its command from Brigadier Grover, later commander of 2nd Division. The brigade fought against the French in Madagascar and embarked for India in January 1943. In January Festing was promoted to command of 36th Division and was replaced as Brigade CO by Brigadier Hugh Stockwell. The 72nd Brigade was raised in England and commanded by Brigadier A.R. Aslett, who had captained the England rugby team before the war.

On 1 September 1944, the division was re-designated as British and on 14 December it received the 26th Indian Infantry Brigade as its third brigade, commanded by Brigadier M.B. Jennings. It took part in operations in the Arakan, re-capturing the tunnels on the Maungdaw–Buthidaung Road. The division moved to Shillong for rest before relocating to Ledo, where it came under the command of General Stilwell’s Northern Combat Area Command. The division’s first objective was to clear the Railway Corridor between Myitkyina and Katha on the Irrawaddy. The first action was at Hill 60 followed by Sahmaw, Thaikwagon, Pinbaw and Mawlu. 29th Brigade occupied Indaw and 72nd took Katha. The division covered about 200 miles and cleared the corridor in five and a half months; they were supplied by the 10th United States Army Air Force. It was the first formation to cross the Irrawaddy in January 1945 and advanced into the Shan States, coming under 14th Army Command. 26th Brigade took Myitson, where the Japanese used flamethrowers for the only time during the Burma campaign. It then took Mongmit on 9 March 1945. The division then moved to Mandalay and Maymyo by air and road to relieve 19th Indian Division. It was then given orders to take Kalaw, although it was finally captured by 19th Indian Division. The 36th Division returned to India in June 1945; 26th Brigade was disbanded in September and the rest of the division was disbanded at Poona in March 1946.

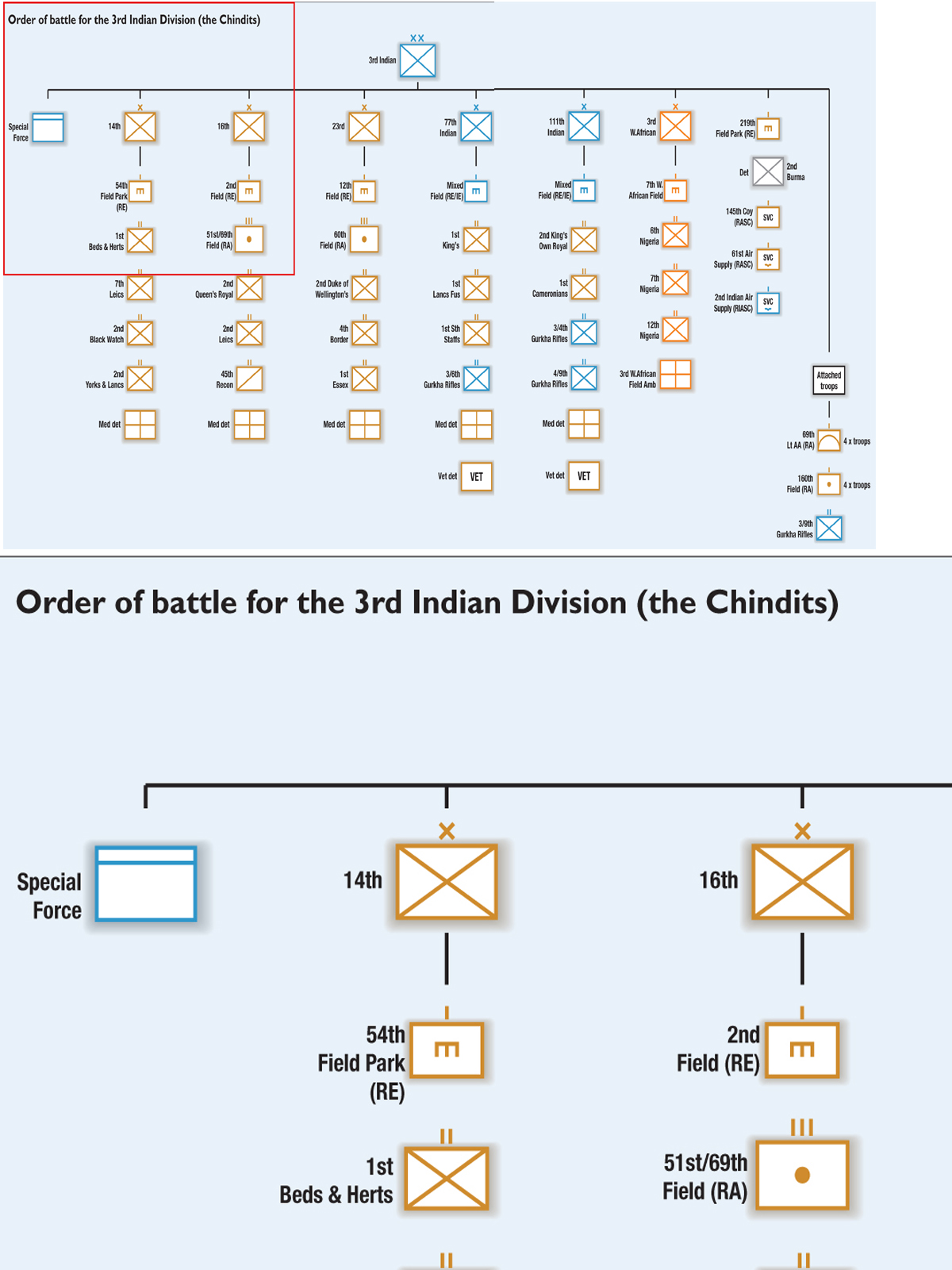

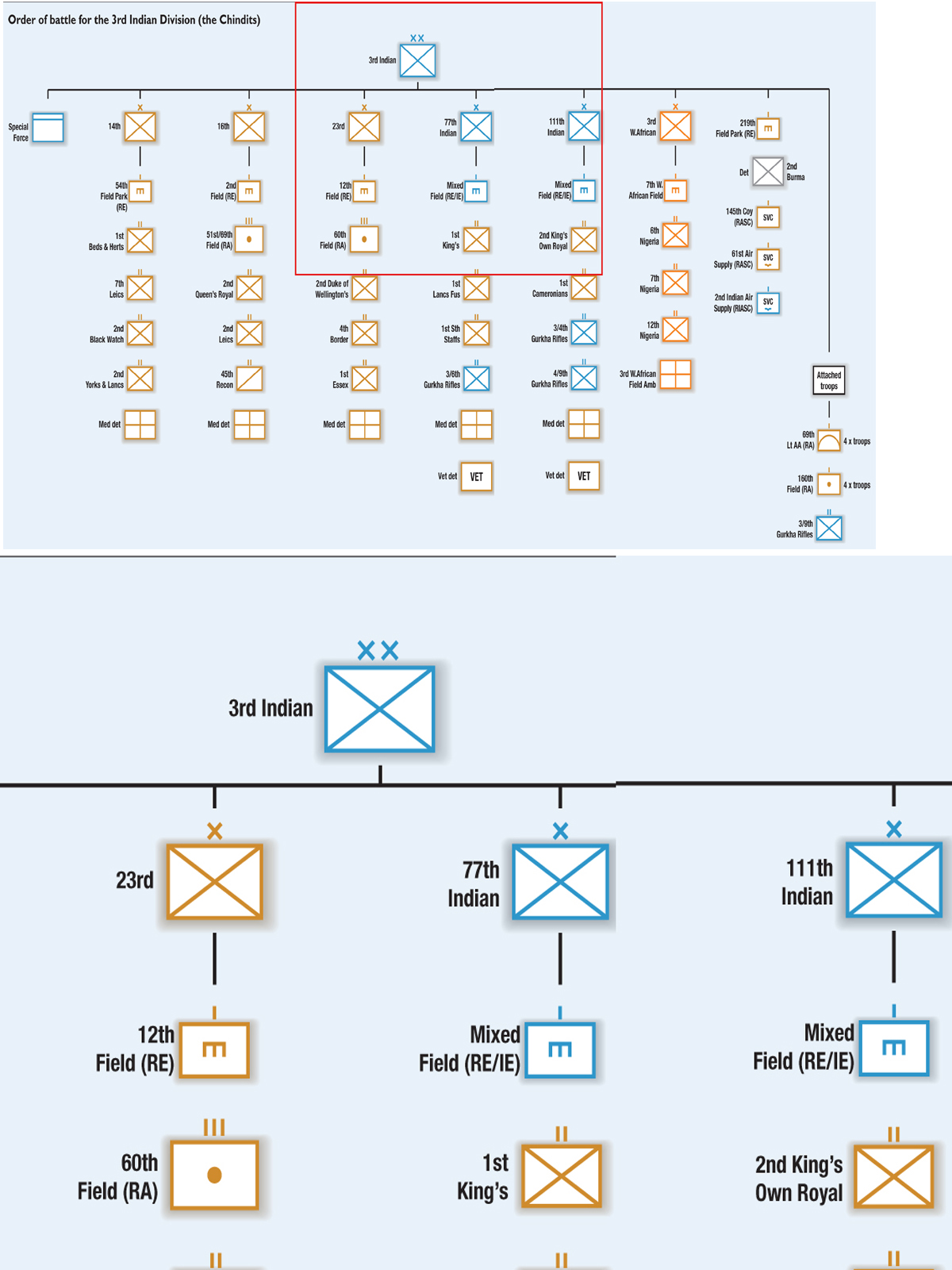

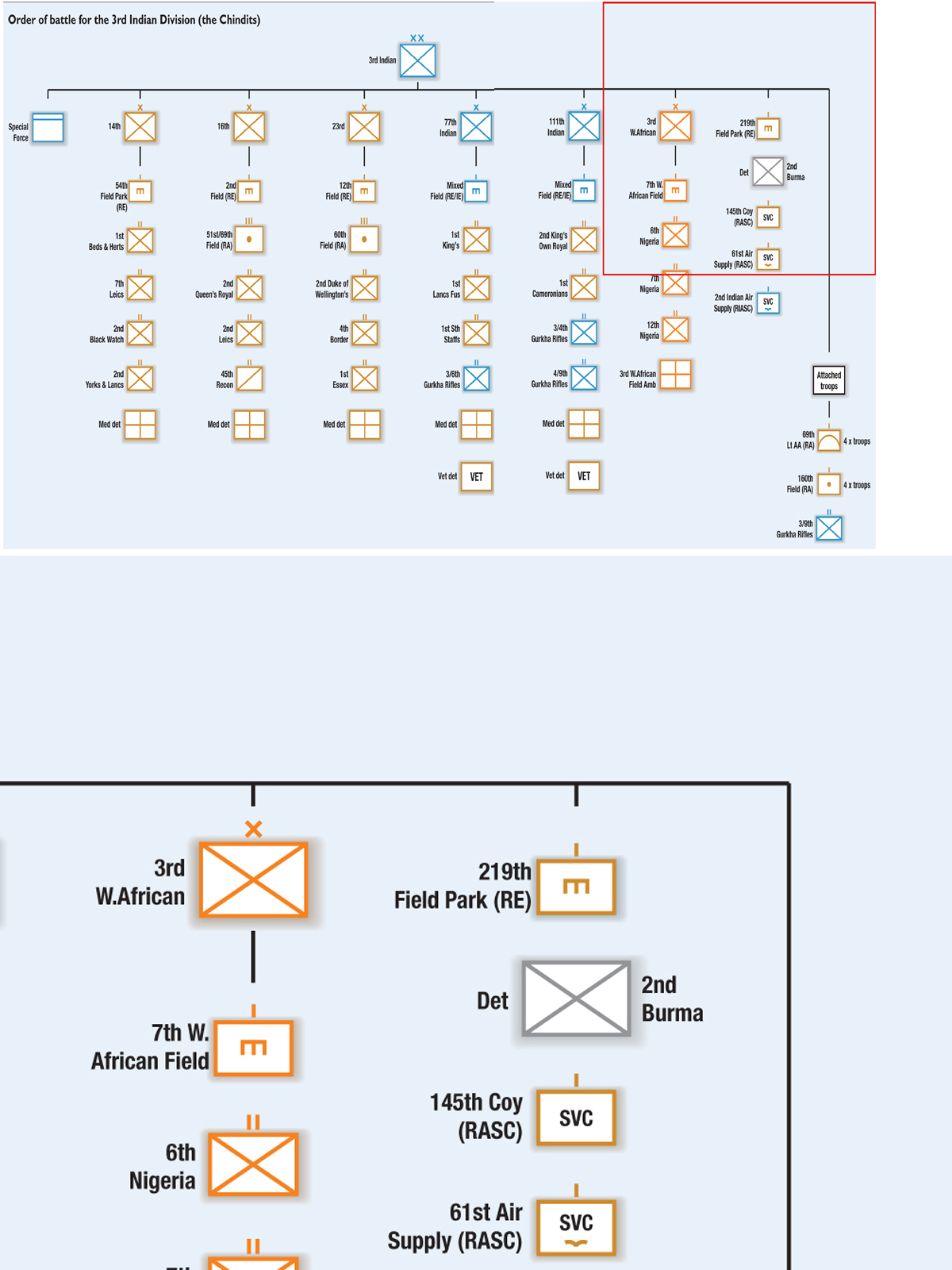

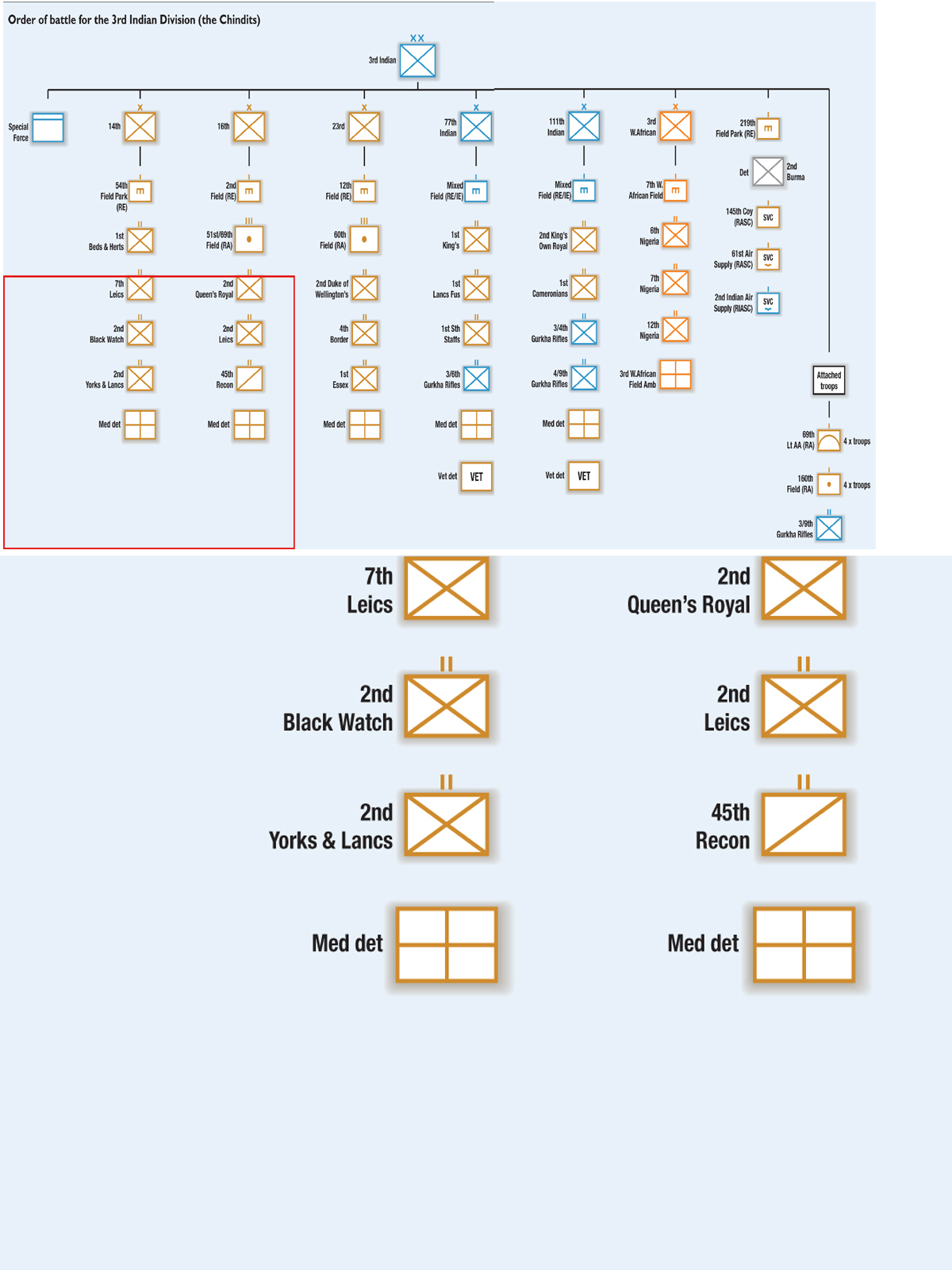

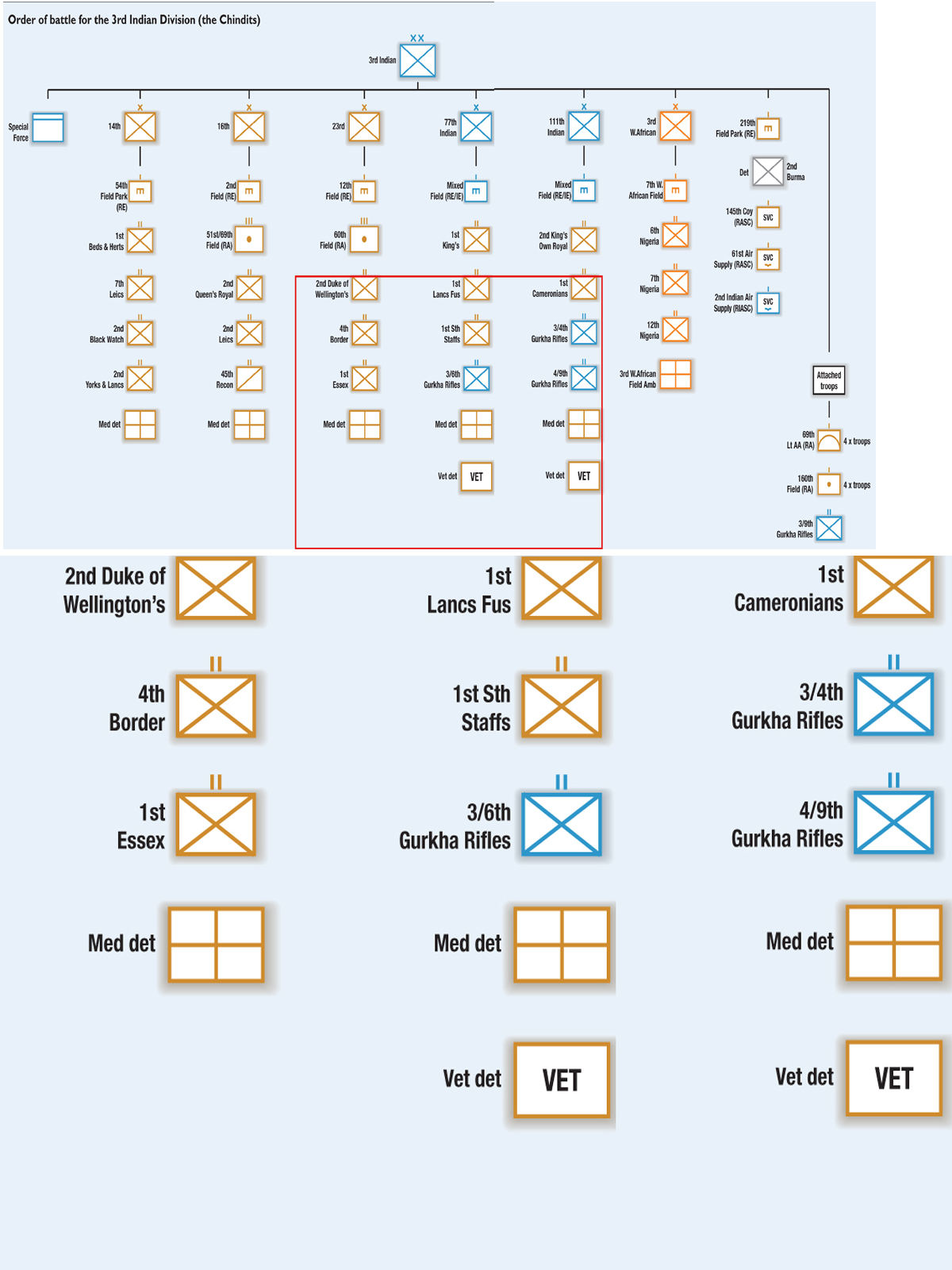

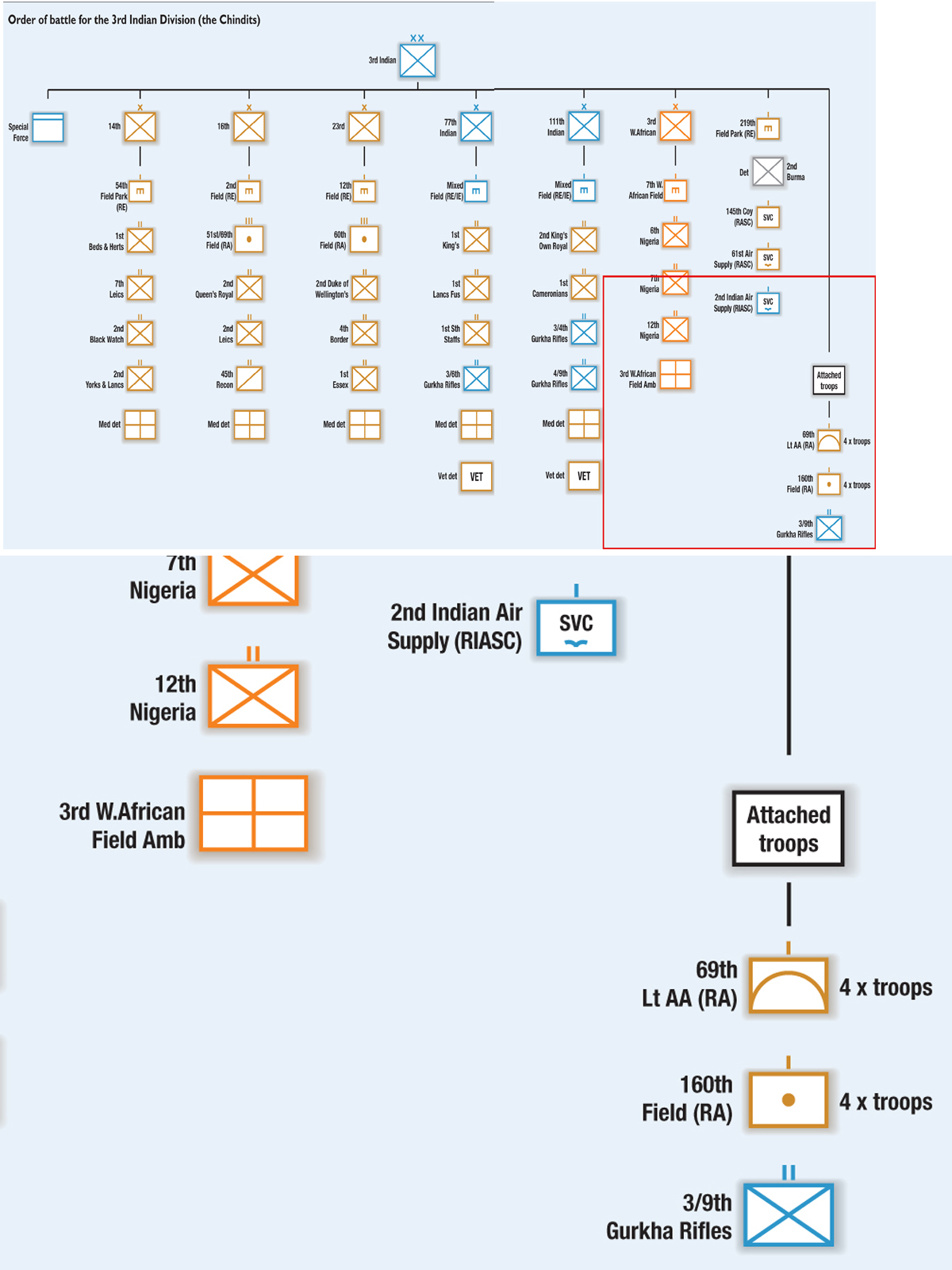

The core element of 3rd Indian Division was formed at Jhansi as a Special Force of long-range penetration troops, after the First Chindit Expedition, on 18 September 1943. The first operation had featured 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, consisting of battalions of Burma Rifles, Gurkhas and the King’s Liverpool Regiment who had been on internal security duties in India. During the operation, the railway lines were cut a number of times between Mandalay and Myitkyina. More importantly, the troops involved emerged from the jungle as heroic figures, lionised by the press as the first British and Commonwealth troops to get the better of the Japanese in the jungle, dispelling the myth of the Japanese ‘supermen’. The operation bolstered morale in both Britain and India. However, only two thirds of the force made it back to India and of those only half were fit for duty again.

The division was made up of 77th and 111th brigades, three British brigades (14th, 16th and 23rd), and the 3rd West African Brigade. These were formed into groups of eight columns each and two wing HQs and a Force HQ. The force was designated as 3rd Indian Division on 1 February 1944. The division’s role in 1944 was to support General Stilwell’s forces ‘behind the lines’ in North Burma. Its second operation was launched in February and was supported by No. 1 Air Commando, US Army Air Force led by Colonel Philip Cochrane, who provided air artillery for the Chindits. The Divisional Commander was Major-General O.C. Wingate, who died in a plane crash on 24 March 1944. He was replaced by Brigadier Walter ‘Joe’ Lentaigne of 111th Brigade. It took three months for them to take the airfield at Myitkyina and another three months before the Japanese evacuated the town. The Chindits were involved in some of the hardest fighting in this operation, holding the strongholds of Aberdeen, Broadway, White City and later Blackpool against repeated Japanese attacks but also disrupting the enemy’s supply lines. Lentaigne did not really share Wingate’s vision and the Chindits were mostly used as infantry rather than as Long Range Penetration Groups under Stilwell’s command. The division was disbanded on 31 March 1945.

In this photo, Brigadier Wingate sits in the passenger seat holding his staff on the way to HQ for a debriefing after the First Chindit Expedition. Wingate was born in India in 1903 and brought up in the Plymouth Brethren. He was educated at Charterhouse, entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich and was commissioned in the Royal Artillery in 1923. He served in the Sudan Defence Force from 1928–33. In 1936 he served on the intelligence staff in Palestine where he became committed to the Zionist cause. He organised and trained a force called Special Night Squads that proved very effective against the Arabs. He was awarded a DSO and a mention in dispatches for his work in Palestine and it was here that he came to the attention of General Wavell.

At the outbreak of World War II, Wingate was a brigade-major with an anti-aircraft unit. He was summoned to the Middle East by General Wavell, now C-in-C Middle East, to organise resistance in Abyssinia. In January 1941 Wingate crossed the frontier with the exiled Emperor Haile Selassie, and Gideon Force comprising Ethiopians, Sudanese and a small number of British officers and NCOs. His force successfully used guerrilla tactics, and entered Addis Ababa on 5 May. He was awarded a bar to the DSO for the Ethiopian campaign. However, Wingate had a temperamental character and on leave in Cairo he attempted suicide.

Wingate was again ordered by Wavell, now C-in-C India, to create a long-range penetration group to operate behind the lines in Japanese-occupied Burma. This new force was reliant on aerial supply and wireless contact. It was an extension of his experiences in Palestine and Ethiopia. His idea was to create a diversion of the enemy forces with regular infantry supported by air firepower, rather than stirring up resistance among the hill tribes, which remained a very secondary objective. After the first operation, Wingate’s ideas developed to the use of strongholds. Wingate attended the Quebec Conference of August 1943 where his ideas were championed by Churchill. As a result he was promoted to Major-General and given the equivalent of a division. On 24 March 1944 he was killed when his plane crashed over North Assam. He is buried in Arlington cemetery, United States.

Wingate was a controversial figure and was often likened to T.E. Lawrence. In fact, he was distantly related to Lawrence. Wingate inspired loyalty and confidence amongst his Chindits but also came in for much criticism from others.

The Burmese dragon on the 3rd Indian Division’s badge was called a Chinthe; its job was to guard pagodas. The resulting nickname, Chindits, stemmed from the formation badge.

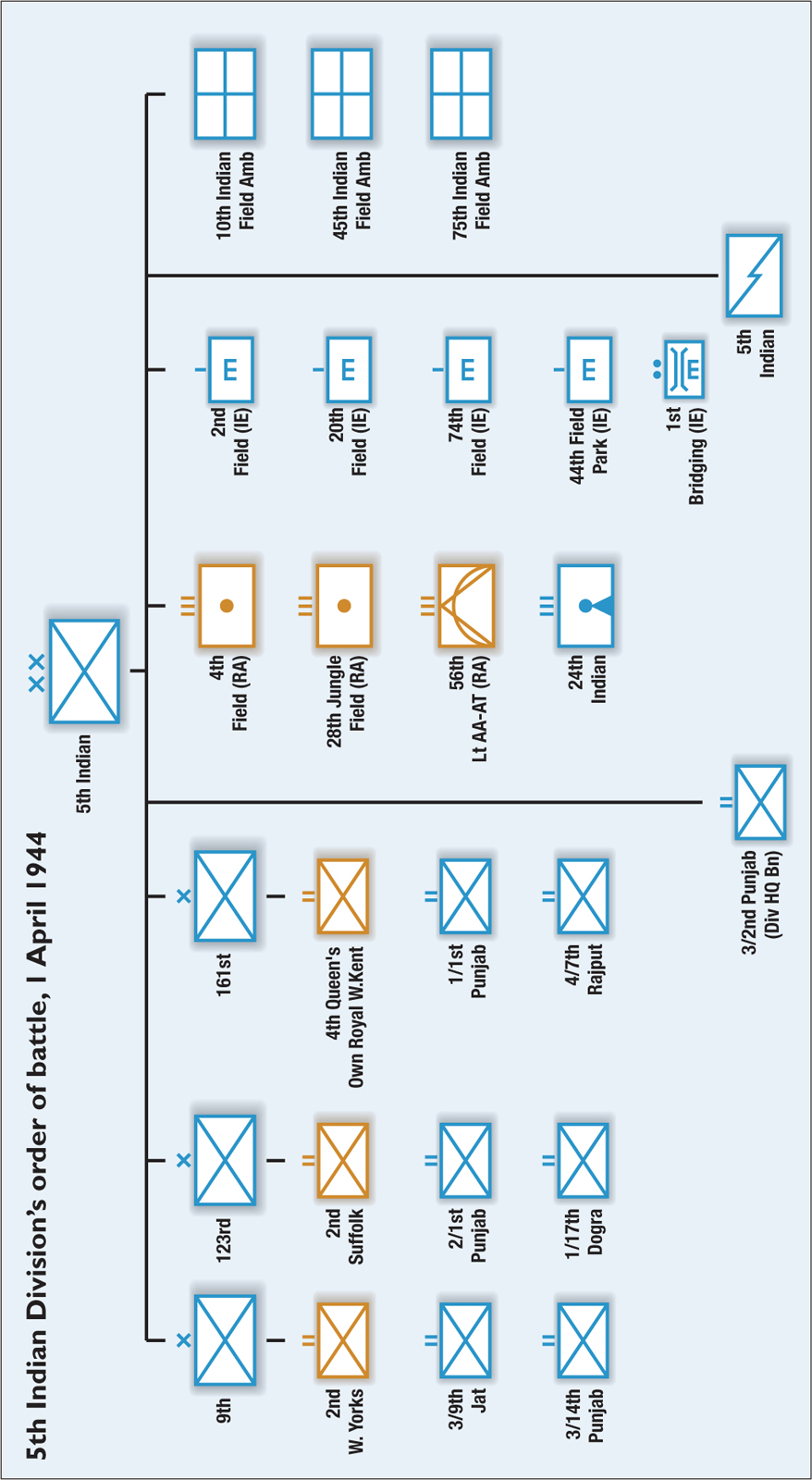

5th Indian Division was formed at Secunderabad in June 1940 under the command of Major-General Lewis Heath. It was transferred to the Middle East in September consisting of only two brigades. The division was involved in many actions in the Middle East, most notably at the Battle of Keren, and in North Africa where it was involved in the defensive battles for El Alamein at Ruweisat Ridge. In May 1942 Major-General Harold Briggs took over divisional command and in October it returned to Iraq to undergo reorganisation as an armoured division with 7th Armoured Brigade. However, it was soon decided that the ‘Fighting Fifth’ would be relocated to the Far East theatre.

The 5th Indian Division started training in June at Chas in Bihar, and then moved to Lohardya, Ranchi, where it reorganised and retrained for fighting in the jungles of Burma. The division was already battle-hardened from its experiences in the Western Desert, but had to adapt to jungle warfare conditions. The amount of motor transport was reduced and animal transport introduced. The 28th Field Regiment was converted to a Jungle Field Regiment with 25-pdrs replaced by 3.7in. howitzers and 3in. mortars. The division also acquired jungle-experienced units such as the 27th Mountain Regiment, which had spent the last five months in the Arakan, and the 123rd Indian Infantry Brigade, which included the 2/1st Punjabis and 1/17th Dogras, which had both fought in the First Arakan. These veterans of the First Arakan helped educate the division in jungle warfare. The new brigade commander of the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade was Brigadier D.F.W. ‘Bunny’ Warren, who had been GSO1 14th Indian Division. Training was undertaken in co-operation with air support and tanks, which together with patrolling was seen as key to jungle warfare tactics.

5th Indian Division’s formation badge was nicknamed the ‘ball of fire’, among other less polite names. It derived from the red circles that were hurriedly painted on the division’s vehicles when instructions were laid out that divisional signs must be displayed. The division had originally adopted the written Urdu figure ‘five’ (a heart-shaped figure) on a black background, but this was later changed for security reasons. The division was one of the few to fight the Italians, the Germans and the Japanese.

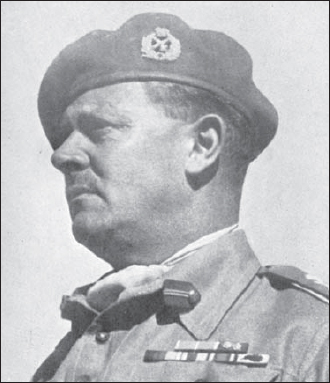

Major-General Harold Briggs (1894–52) was Divisional Commander of 5th Indian Division from May 1942 until July 1944. After the war, he was Director of Operations in Malaya, 1950–51 and was responsible for the Briggs Plan.

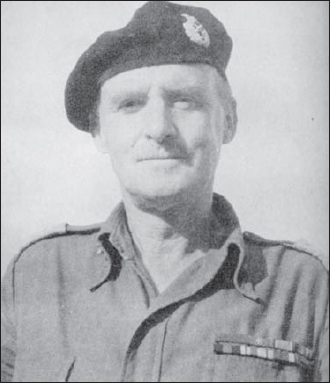

Major-General D.F.W. Warren was brigade commander of 161st Indian Infantry Brigade in the Arakan and at Kohima. His nicknames included ‘Bunny’, ‘Daddy’ and ‘Freddie’. He was a popular commander of 5th Indian Division from September 1944 but was killed when his plane went down on the way to Kalemyo, on 11 February 1945.

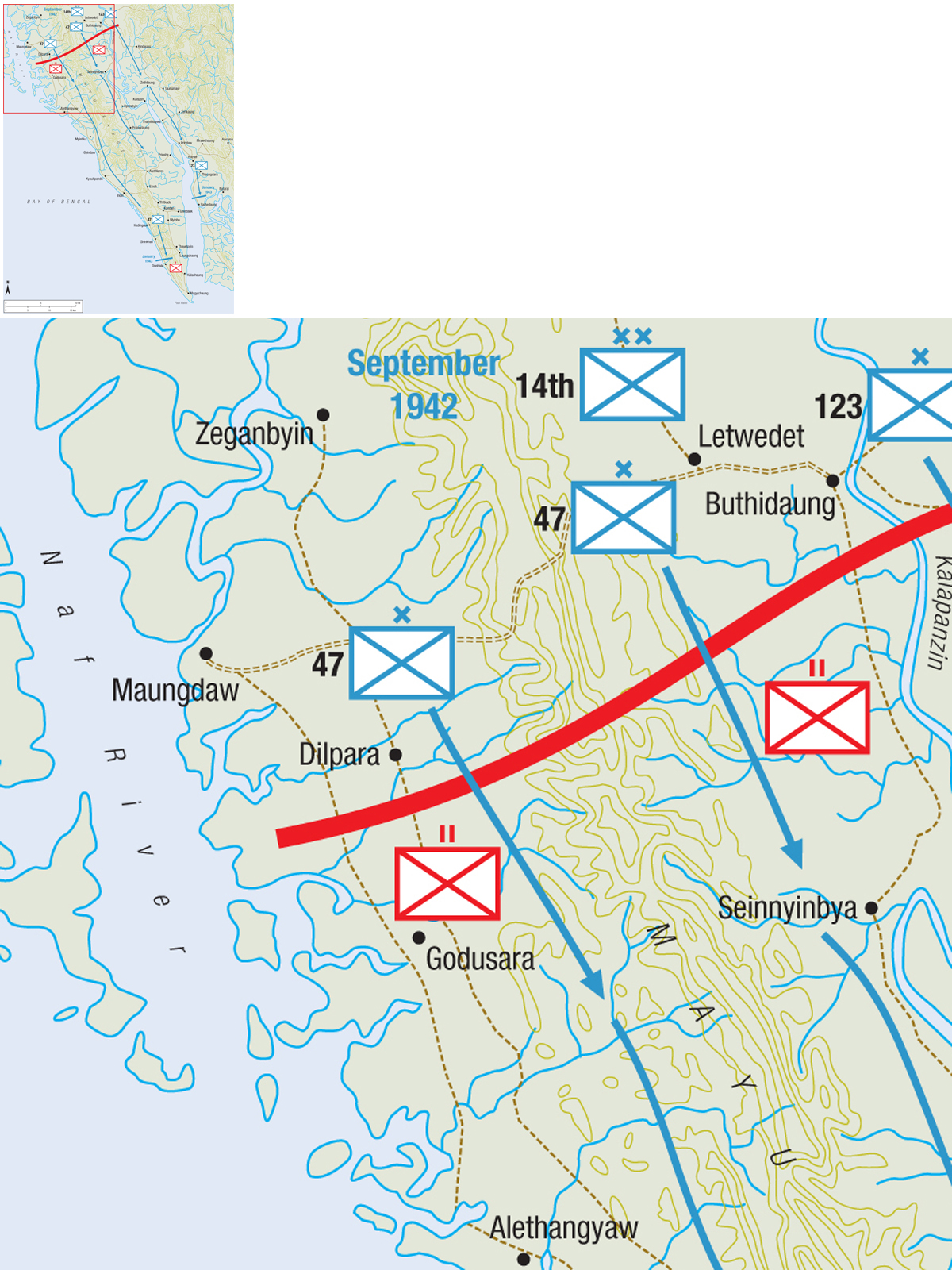

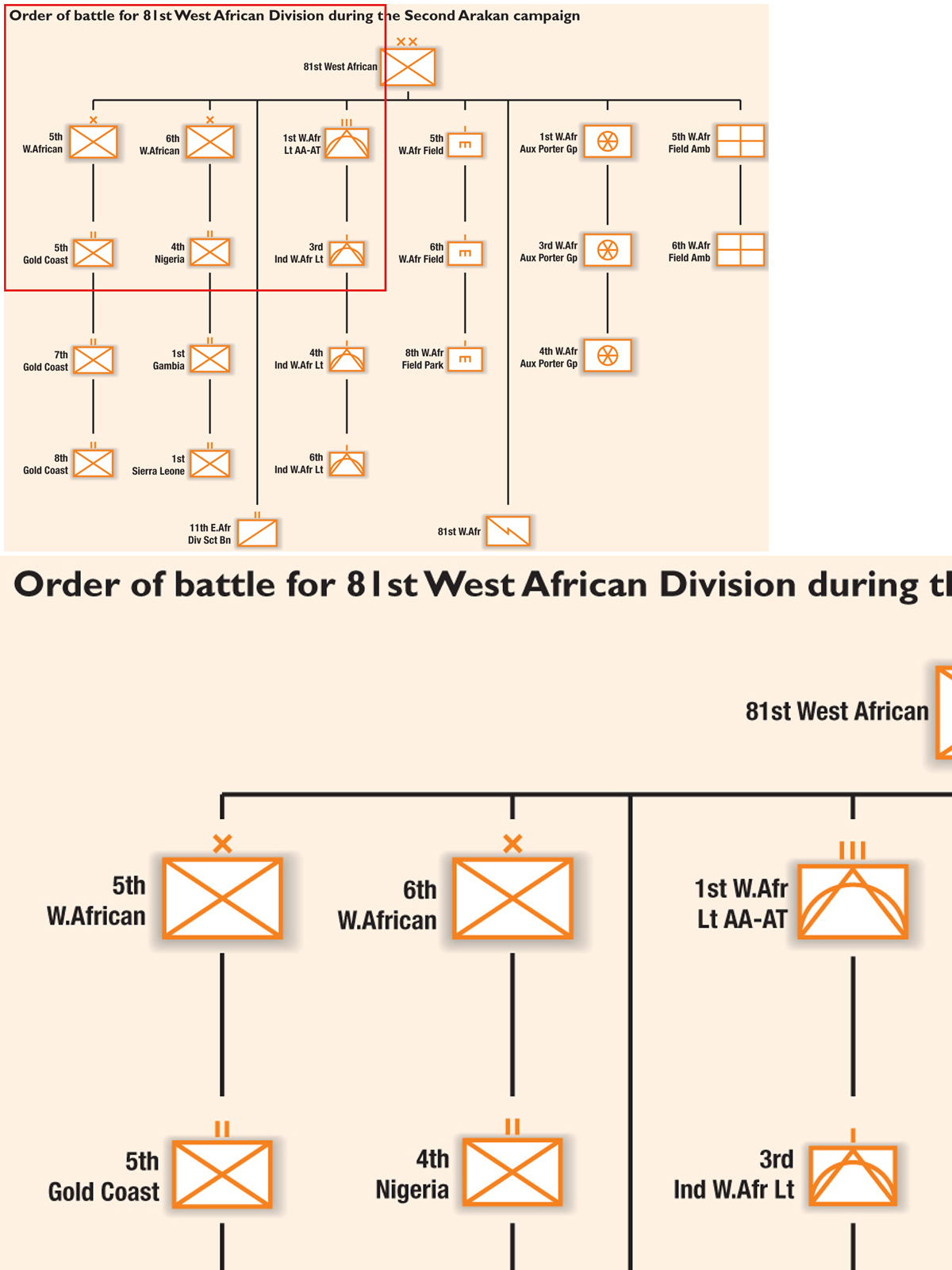

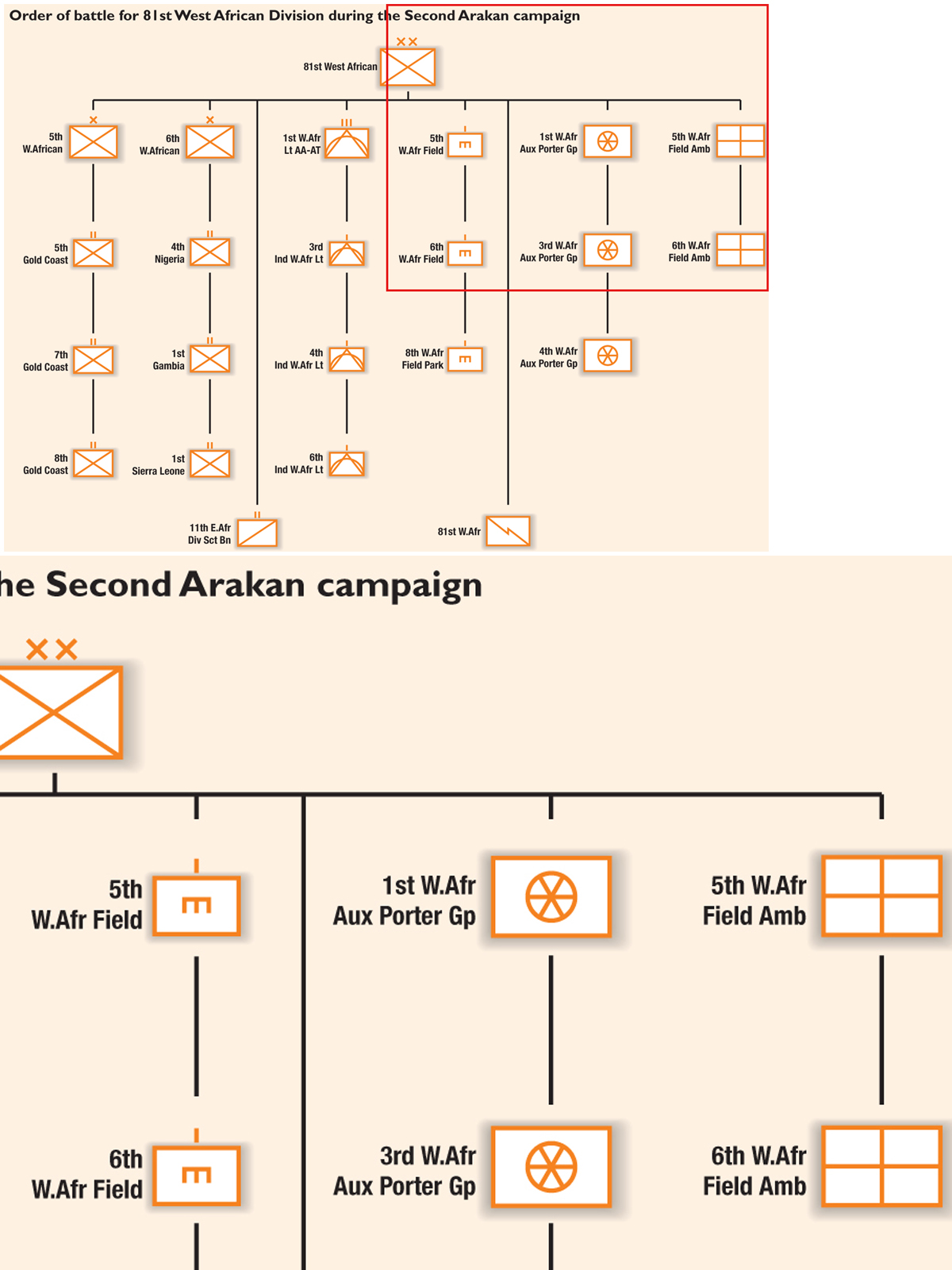

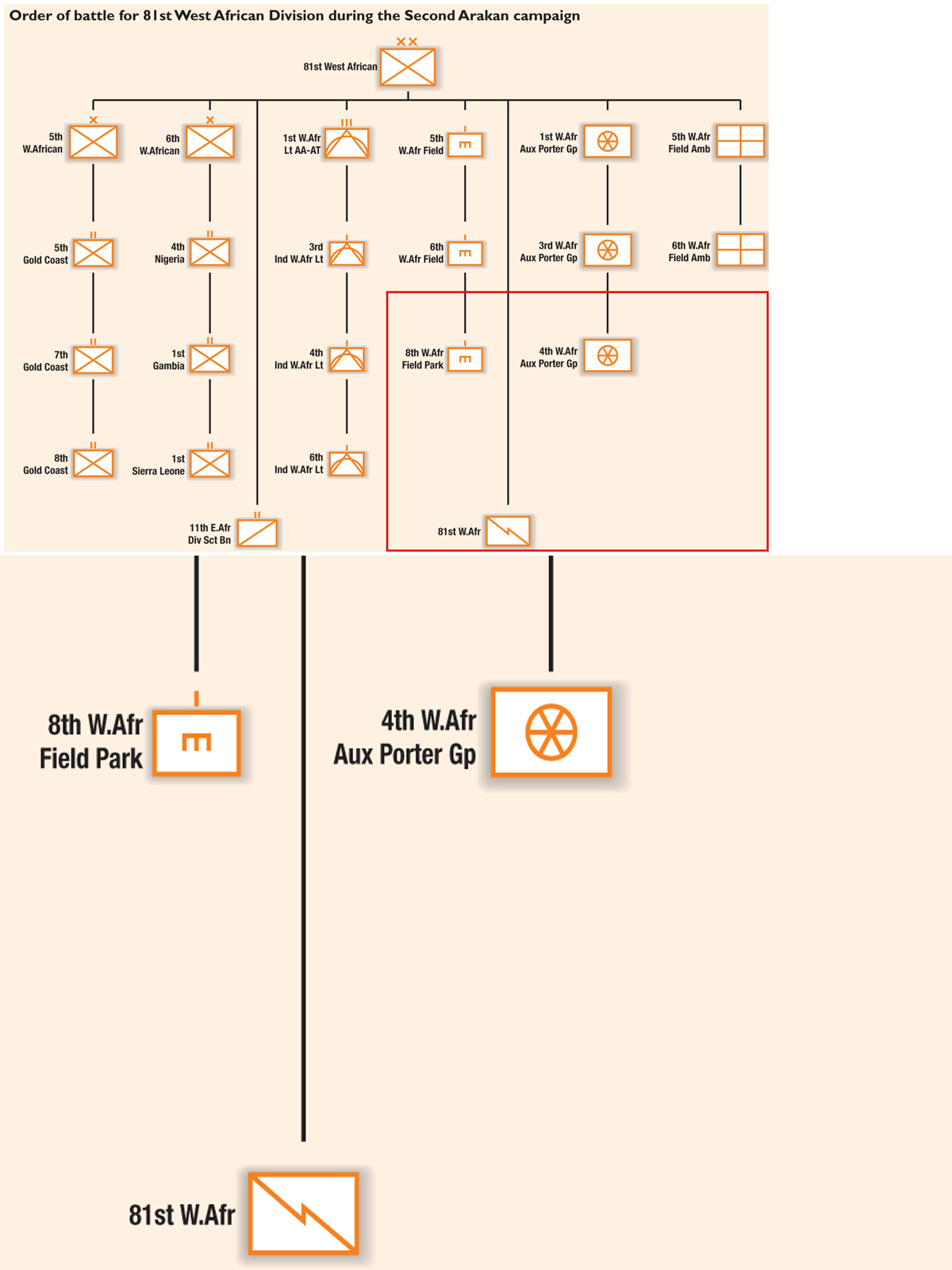

Both the 5th and 7th Indian divisions underwent training in co-operation with the Royal Air Force for air supply. Both divisions were the first properly-trained formations of the Indian Army to fight in the Far East, in the Second Arakan campaign. They formed 15th Indian Corps, under the command of Lieutenant-General A.F.P. Christison, and were earmarked for the retaking of the Maungdaw–Buthedaung tunnel road. They relieved 26th Indian Division in late 1943. The plan was for 5th Indian Division to advance down the western side of the Mayu Range with Razibil fortress as its objective, while 7th Indian Division moved down the eastern side towards Buthedaung. The divisions were supported by the Lee tanks of the 25th Dragoons, while 81st West African Division covered their flank by advancing into the Kaladin valley to capture Kyauktaw.

In contrast to the First Arakan, the divisions were allowed time to acclimatise themselves to jungle warfare and gain confidence in the jungle through patrolling. The size and scope of the fighting gradually increased with actions at brigade level, when the Commonwealth forces had overwhelming superiority of numbers over the enemy. For instance, the 5th Indian Division’s first major action was a direct attack on Razabil, made by 161st Indian Infantry Brigade, supported by bombers, dive-bombers and tanks. It was a failure, as the Japanese defenders were heavily entrenched, but the division quickly learned about the combat use of hooks, encirclement and tank support in their attacks. These tactics had been taught during training and for the first time were put into practice. Although unsuccessful, the experience gained helped shift them one step closer to defeating the Japanese in the jungle.

9th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Evans, helped to relieve 7th Indian Division at the Battle of the Admin Box, whilst the rest of the division retook the Ngakydauk Pass. The second attack on Razibil on 12 March was more successful. During this operation 161st Brigade hooked around the fortress and cut off the enemy’s lines of communication, while 123rd Brigade simulated a frontal attack in combination with an artillery bombardment. 9th Brigade was in reserve. The enemy was caught unawares, but unfortunately the advantage was not pressed home and the Japanese slipped away during the night.

The formation badge of the 7th Indian Division, showing a gold arrow on a black cloth backing; as a result, it was also known as the ‘Golden Arrow’ division. The division was formed in Attock on the North-West Frontier on 1 October 1940, and its original badge featured a blue ball. The Divisional Commander, Major-General Frank Messervy, invested the arrow with the meaning: ‘Forward to the target, straight and true, no withdrawal.’

The division was then transferred by air to the Kohima–Imphal front and continued afterwards on the Tiddim Road; it saw continuous action for 14 months. The division was in action again for the Battle of Meiktila and was earmarked for Operation Zipper. It was involved in internal security duties in Singapore and Southern Malaya, then was transferred to Java, and began returning to India in April 1946.

The 7th Indian Division moved to Chhindwara in January 1943 and was one of the first formations to embark on jungle training. The training team attached to the division by GHQ was led by Lieutenant-Colonel Marindin, who had participated in the retreat from Burma, with jungle lore taught by Captain Edgar Peacock, a forestry officer from Burma. By March, formation training was underway. There were exercises in co-operation with artillery, mortars and medium machine guns, called ‘Blitz’ tactics. From May to September the division carried out training in co-operation with the artillery and the 25th Dragoons, Royal Armoured Corps.

Further action in the Arakan was delayed by a major Japanese offensive, Operation Ha-Go, whose objective was to draw Allied troops into the Arakan, creating a diversion for the main Japanese advance towards the Imphal Plain. The Japanese plan in the Arakan was for the 55th Japanese Division to outflank 7th Indian Division and then split 7th and 5th Indian divisions apart, before destroying each in turn. The Japanese advance on 4 February 1944 was swift and Major-General Messervy’s 7th Indian Divisional HQ at Launggyaung was overrun, causing a breakdown in communications. Brigadier Geoffrey Evans was ordered to defend the Administrative area of 7th Division at Sinzweya, later called the ‘Admin Box’. This formed a refuge for Messervy and what remained of his HQ, who resumed command using wireless to contact his widely-dispersed troops. The defending troops prepared for all-round defence depending on air supply, and attacking the enemy positions and supply lines when possible. The avoidance of a disorganised withdrawal and the creation of an air-supplied defensive box was a feature learnt from the earlier campaigns and practiced during training.

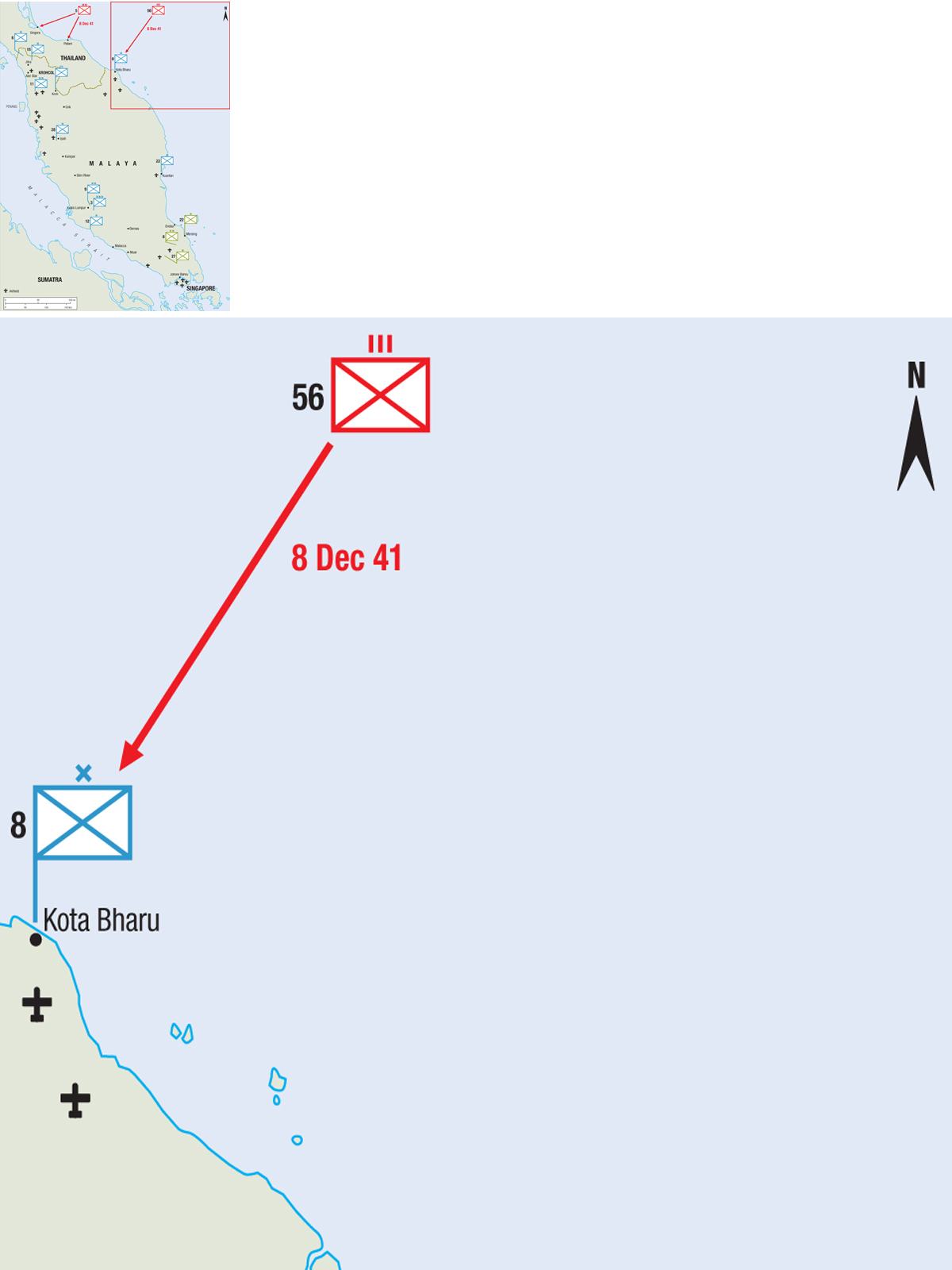

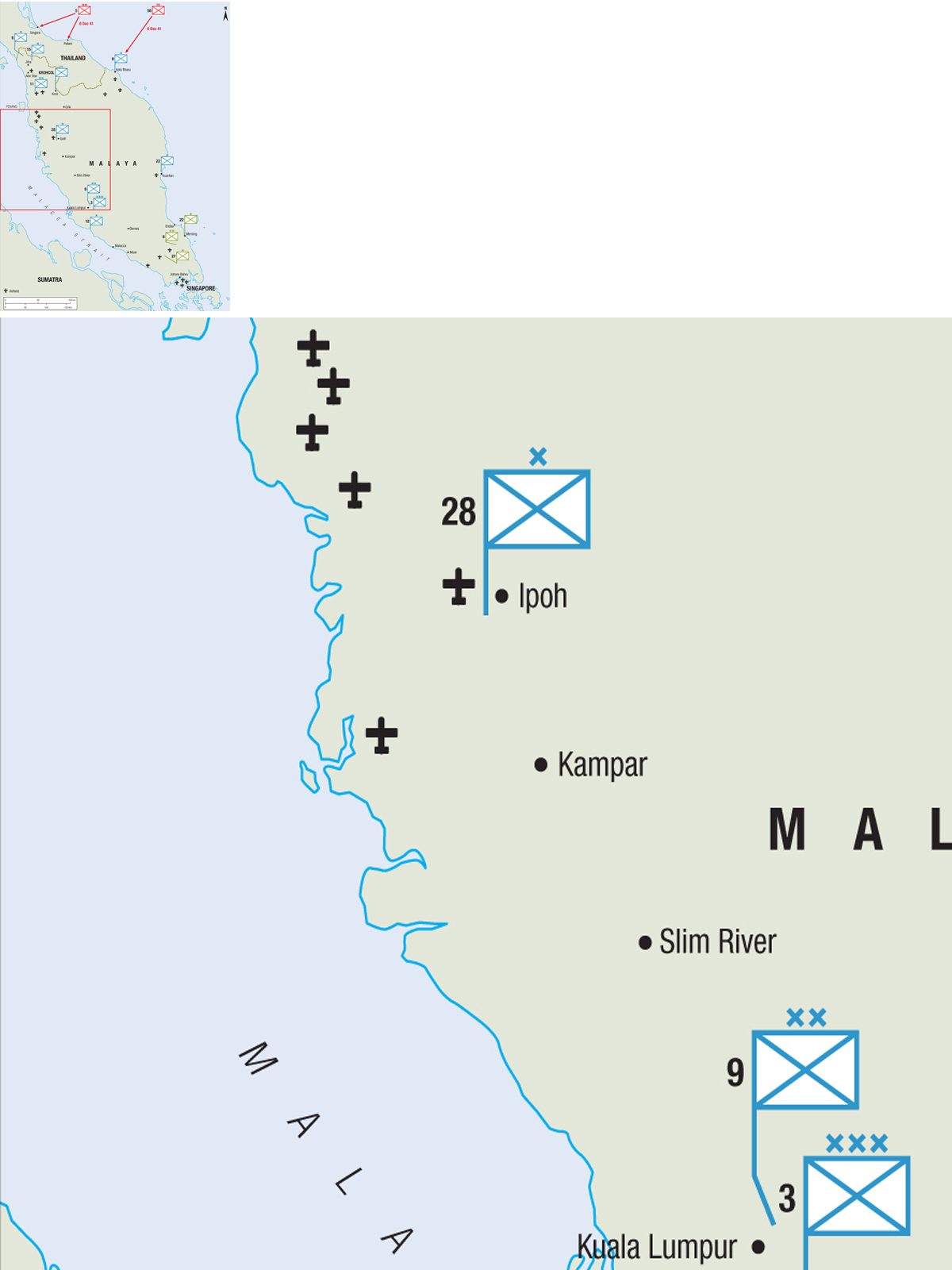

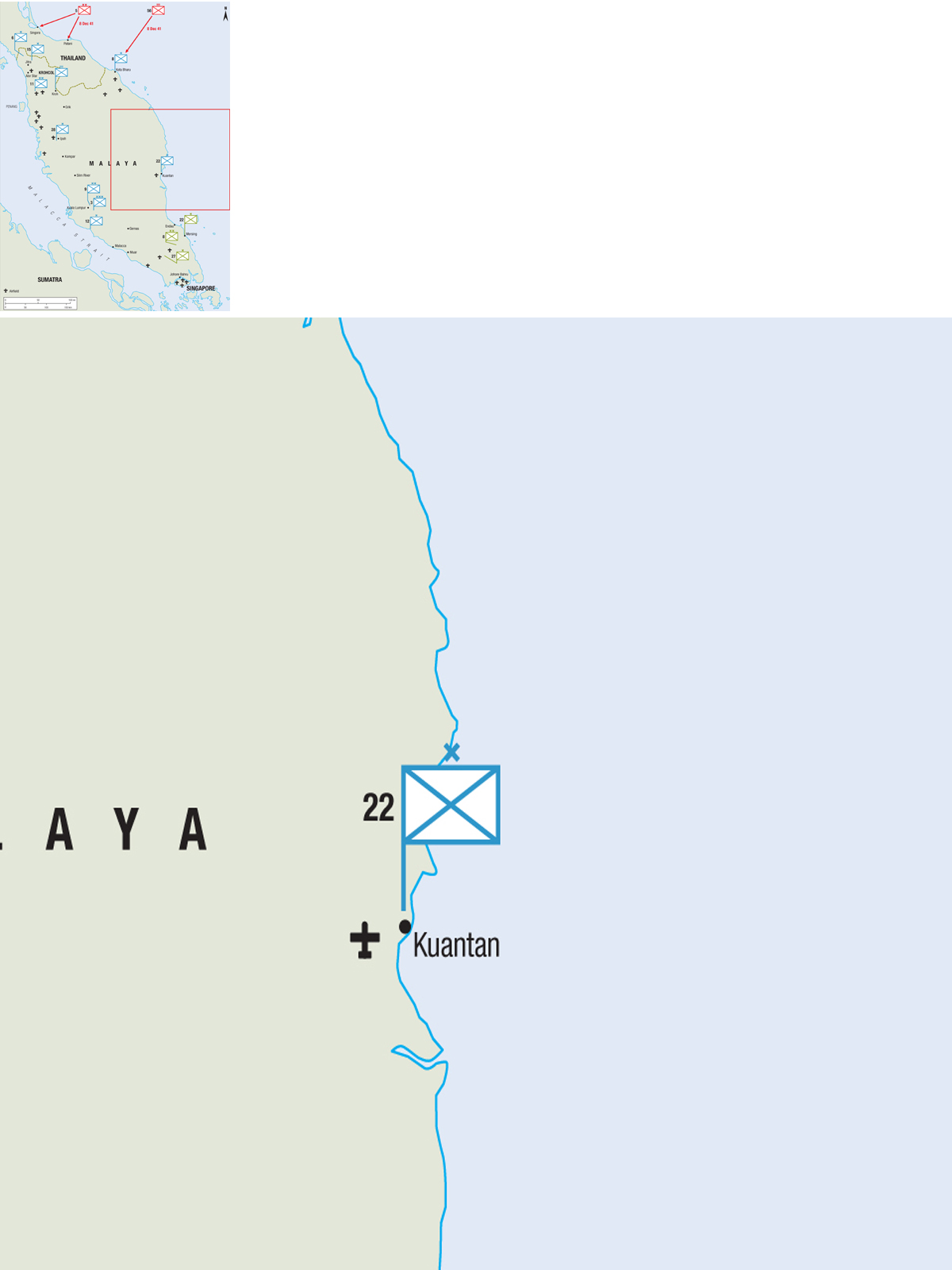

Malaya, with the dispositions of the British and Commonwealth formations, on 8 December 1941.

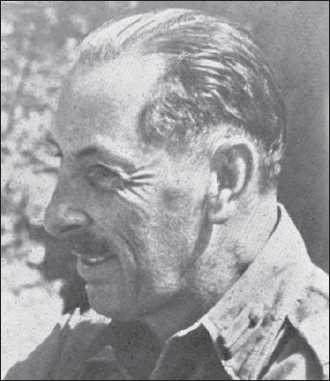

Major-General Geoffrey Evans (1901–87) was the Commanding Officer of 9th Indian Infantry Brigade during the Battle of Admin Box. He went on to command both the 5th and 7th Indian divisions.

Major-General Frank Messervy took over command of 7th Indian Division from Major-General Corbett in July 1943. He had served with an Indian cavalry regiment, Hodson’s Horse, during World War I. In World War II he had previously commanded Gazelle Force in Eritrea, 4th Indian Division and 7th Armoured Division (The Desert Rats) in the Western Desert and was well known for his escape from the Germans by impersonating an old soldier. He was nicknamed ‘General Frank’ by the soldiers of 7th Division. Messervy was made commander of IV Corps on 8 December 1944, and was later replaced by Major-General Geoffrey Evans. (IWM IND

The area chosen for the Admin Box was a flat, saucer-shaped area and thus was difficult to defend as it was surrounded by jungle-covered hills. At its centre was the highest position of 150ft called Ammunition Hill, with ammunition and ordnance at its base. By 10 February the Japanese had occupied most of the surrounding high ground, which dominated the Box. However, once the Japanese positions had been located by an observation post on Ammunition Hill, artillery with tank support brought overwhelming firepower down on them. This had the added advantage of destroying much of the jungle cover that would have facilitated future Japanese attacks.

In addition to the unfavourable defensive position, there was originally only one defending combatant unit, the 24th Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment. There was insufficient personnel to form a continuous line of defenders, and the defence had to rely on the counter-attacking abilities of newly arrived reinforcements, including two squadrons of the 25th Dragoons and a battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment. On 7 February Messervy also ordered the 4/8th Gurkhas to come into the Box to take over the eastern gate and an important position called Point 315. This position had been previously undefended due to the lack of troops but was now seen as vital since it dominated the Box. The Gurkhas were attacked before they could reach their target and were initially forced back behind the perimeter, but a counter-attack by the 25th Dragoons, supported by the West Yorkshires, allowed them to take up their new position.

The British used infantry and tank co-operation tactics, originally developed at Ranchi and refined at Razabil, in counter-attacks against the Japanese. On 12 February, Artillery Hill was subjected to a daylight attack by the Japanese. It was defended by the 24th AA-AT Regiment acting as infantry. The enemy hid in the jungle and took the position by surprise. A counter-attack by the West Yorkshires was unsuccessful, so two troops of ‘C’ Squadron, 25th Dragoons, were deployed firing high-explosive shells to clear the jungle undergrowth. When the tanks were at a reasonably close distance, solid shot was used to loosen the earth around Japanese bunkers and then high-explosive shells were used to destroy them. Finally, when the tanks were within a range of 100–300 yards, they fired their machine guns over the crest, allowing the infantry to advance without the threat of shell splinters. The infantry advanced to within 15 yards of the Japanese position before attacking with grenades and bayonets and capturing the hill. This action marked the beginning of the new techniques in tank and infantry co-operation and was in use for the remainder of the war.

Throughout its encirclement, the Admin Box was sustained by air supply. This was the first example of its large-scale use in the Burma campaign, with Dakotas successfully dropping food, ammunition and equipment. Not only was essential equipment dropped but mail and copies of SEAC, the paper of the Armed Forces in South-East Asia, were also delivered, which helped sustain morale.

The final Japanese attack on the Box came on 14 February. It was repulsed by the defending troops, and after this Japanese effectiveness rapidly declined due to the lack of supplies, since they had relied on capturing abandoned British supplies as in previous campaigns. The Box was eventually relieved on 27 February. According to Japanese sources the all-round fluid defence of the Box supported by air power could have been defeated only by overwhelming firepower, which the Japanese did not possess.

The Battle of the Admin Box and the defence of similar defensive boxes occupied by the remainder of the 5th and 7th Indian divisions heralded the turning point of the Burma campaign. The myth of the Japanese superman was emphatically destroyed, and the events gave a huge boost to the morale of the 14th Army as well as to the civilian populations in India and Britain. Japanese tactics in the jungle had been effective up until this point, but the IJA had learnt nothing new. In the attack in the Arakan the IJA had relied on the Commonwealth forces retreating and leaving the supplies behind, and as a result they only had supplies for ten days.

The formation badge of 9th Indian Division.

The division also fought at Kohima and Imphal and in the pursuit to Ukhrul. It later advanced to Pauk and established a bridgehead over the Irrawaddy. The 7th were also involved in the last major battle in Burma, at Sittang, before disarming Japanese troops and evacuating prisoners of war in Siam.

The division was formed in Quetta in September 1940. It was sent to Malaya in March and April 1941. 8th and 22nd Indian Infantry brigades came under its command and it was responsible for the defence of the eastern coast of Malaya stretching from Kota Bharu to Kuantan. It was on Kuantan Airfield that Lieutenant-Colonel A.E. Cumming, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment won the Victoria Cross for conspicuous gallantry. During the withdrawal of the battalion and Brigade HQ, an enemy force attacked; Cumming and a small party of soldiers counter-attacked and held the enemy off until the whole party had become casualties and he had received two bayonet wounds in his stomach. Despite these wounds he drove in a carrier for more than an hour collecting the remnants of the battalion. He was wounded twice more and lost consciousness, but when the driver of the carrier tried to evacuate him, he recovered and insisted on remaining until he and the driver were the last survivors in the vicinity. After the surrender of Singapore, Brigadier Cumming led a small party of British and Indian officers through Japanese lines managing to evade capture and eventually reach Sumatra. The 9th Indian Division was broken up on arrival on Singapore Island on 31 January 1942.

The 11th Indian Division was formed at Kuala Lumpur on 12 October 1940, under the command of Major-General D.M. Murray-Lyon. The formation, part of III Indian Corps, was responsible for the defence of Northern Malaya.

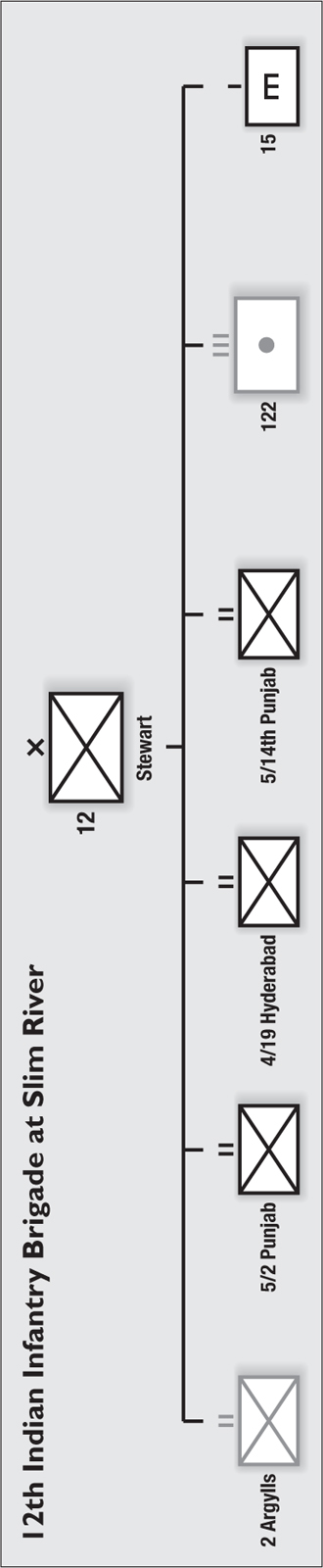

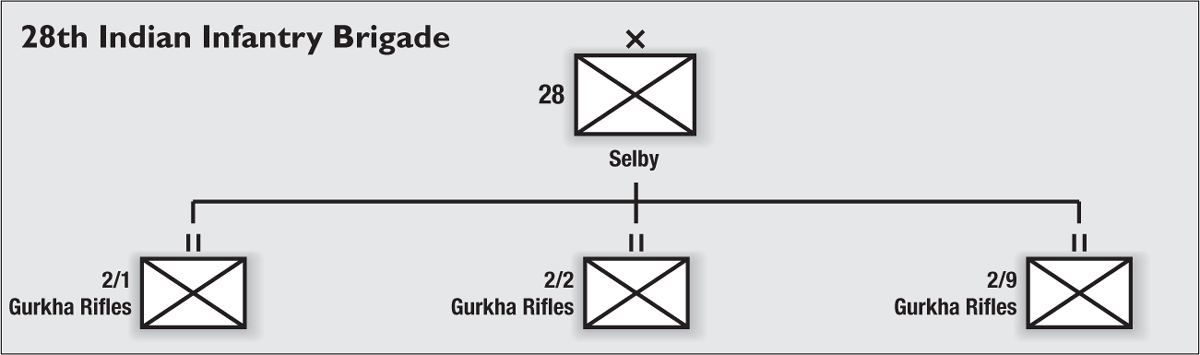

The Japanese 25th Army invaded the Malayan mainland at Kota Bahru on 8 December 1941, with unopposed landings in Thailand at Singora and Patani. Operation Matador, a British pre-emptive plan to forestall the Japanese landings, was not ordered in time. The Japanese air forces quickly gained superiority over the obsolescent planes of the Royal Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force. This, in addition to the sinking of HMS Renown and HMS Repulse on 9 December, meant that after three days the defence of Malaya and Singapore was the army’s responsibility alone, without any significant support from the other two services. General Percival’s plan for the army was for III Indian Corps under General Heath, comprising 9th and 11th Indian divisions with 28th Indian Infantry Brigade, to be stationed in the north and on the east coast of Malaya to forestall the Japanese forces and provide time for reinforcements to arrive in theatre from overseas.

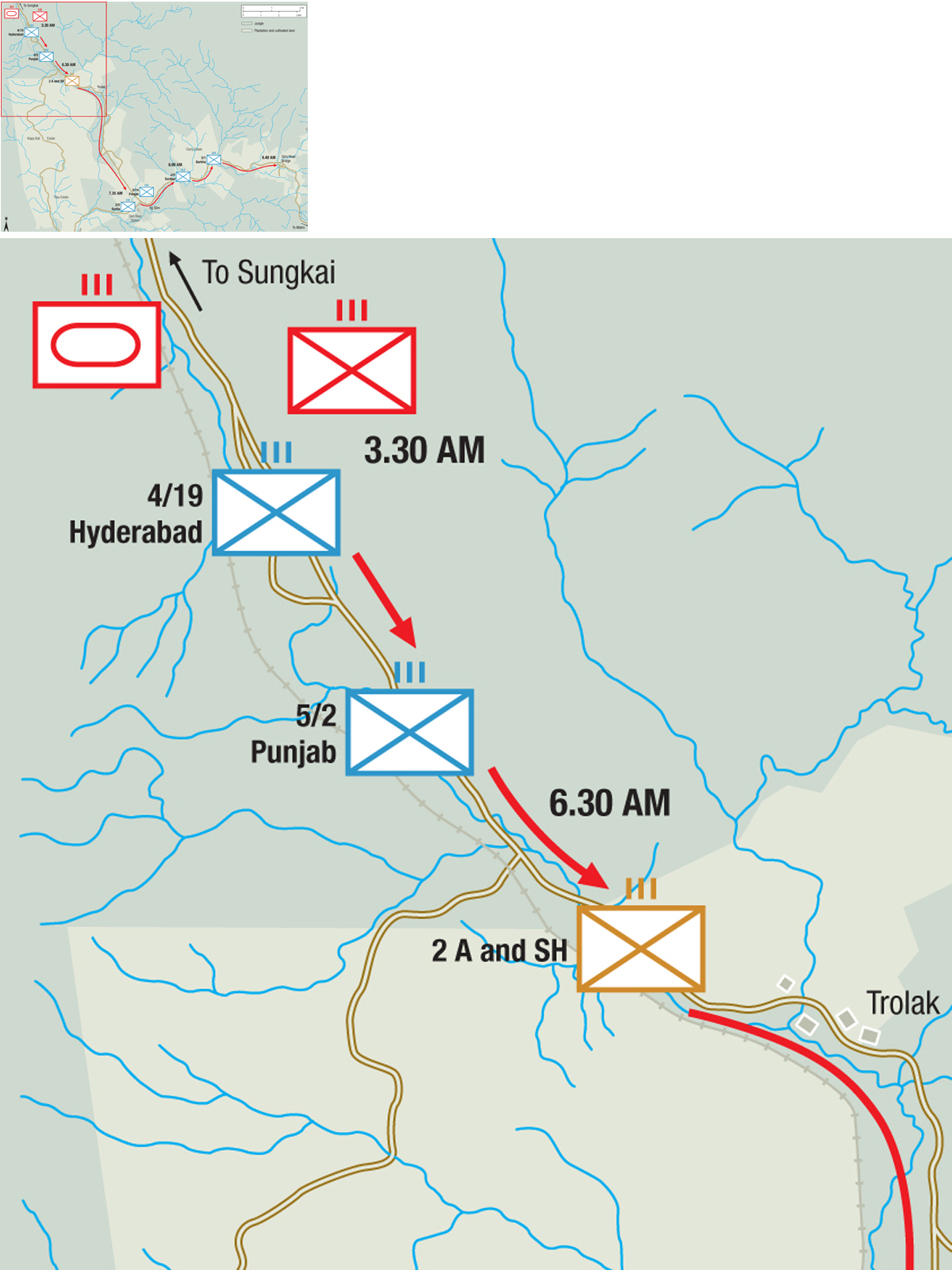

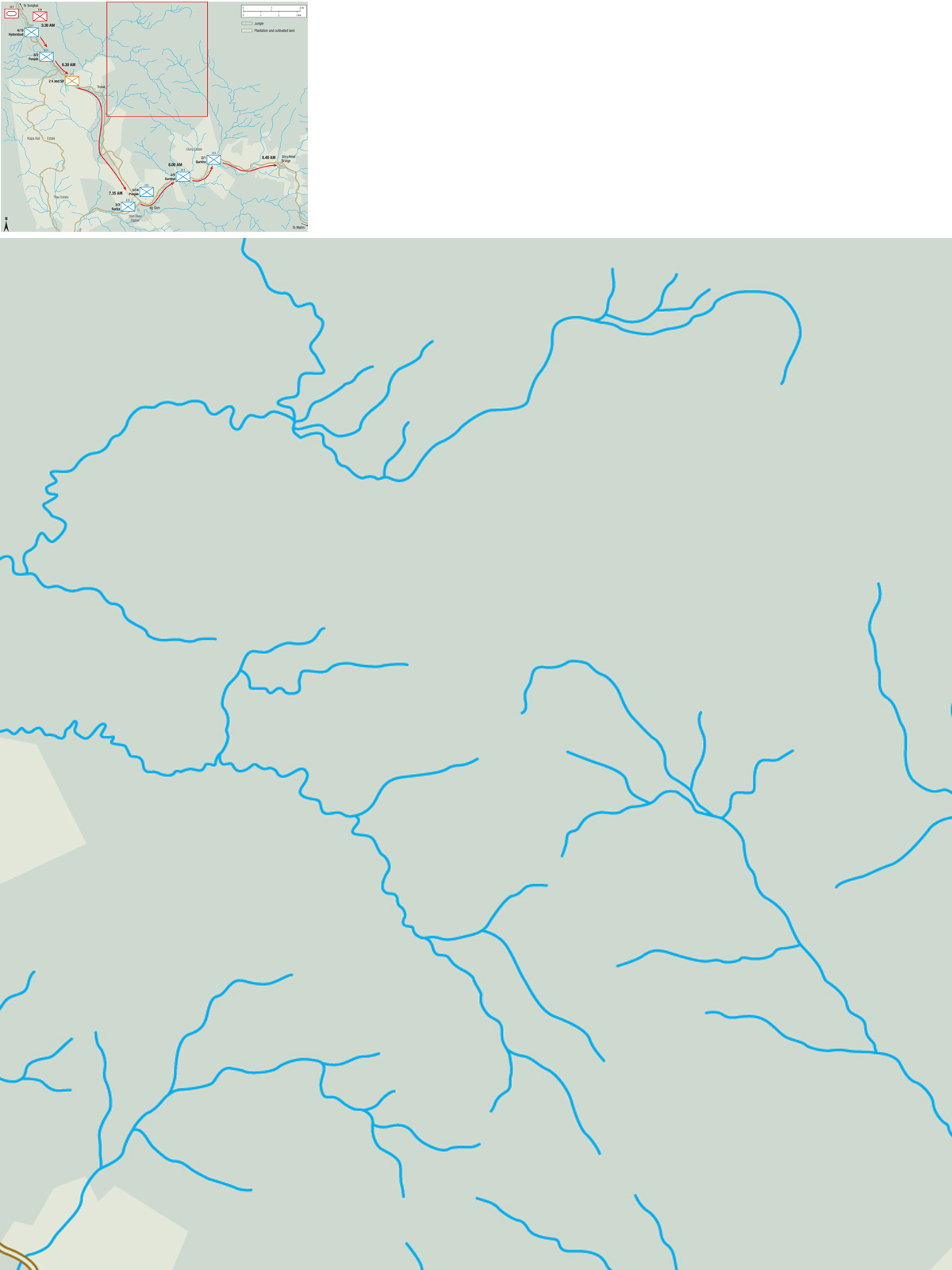

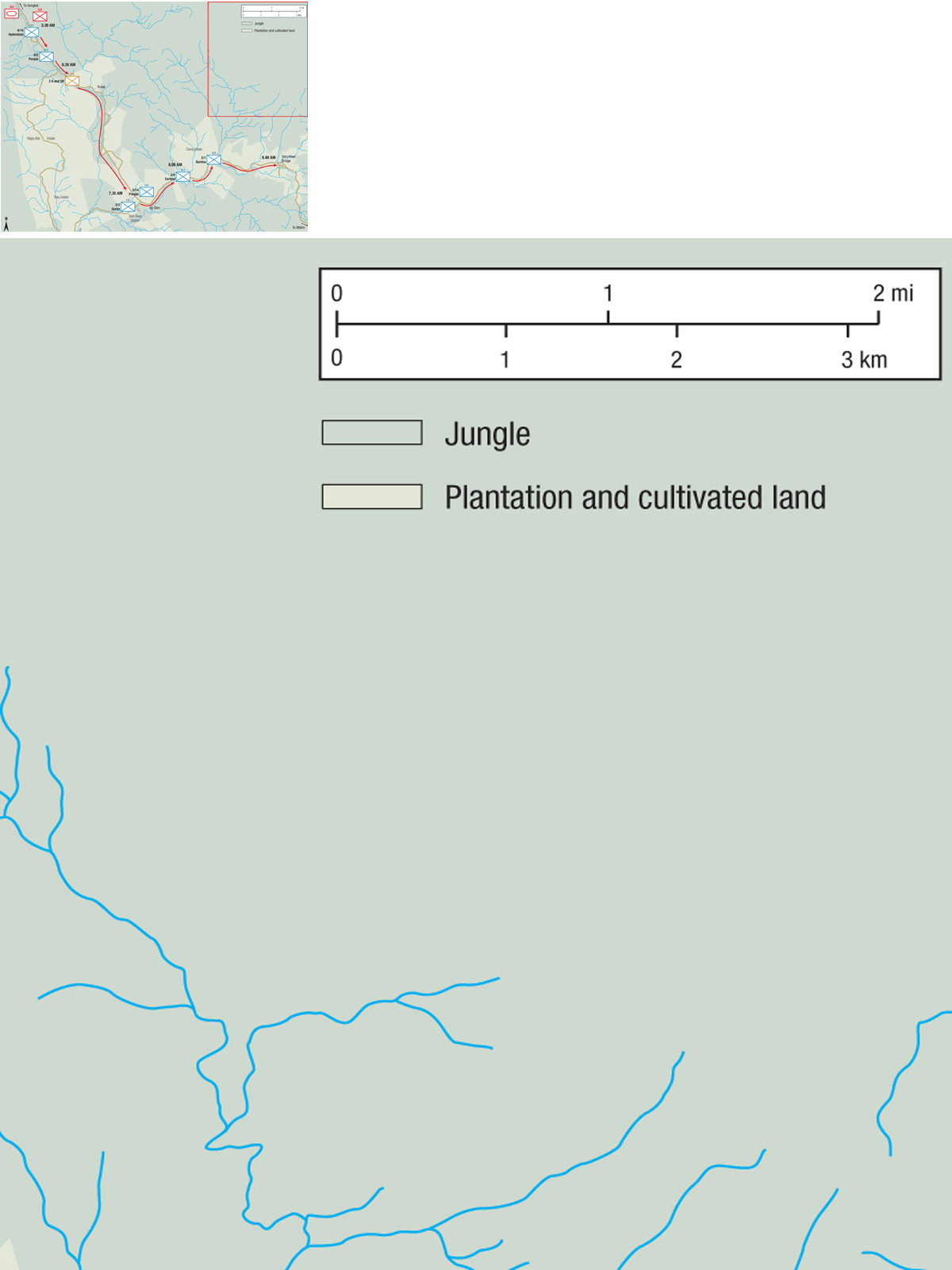

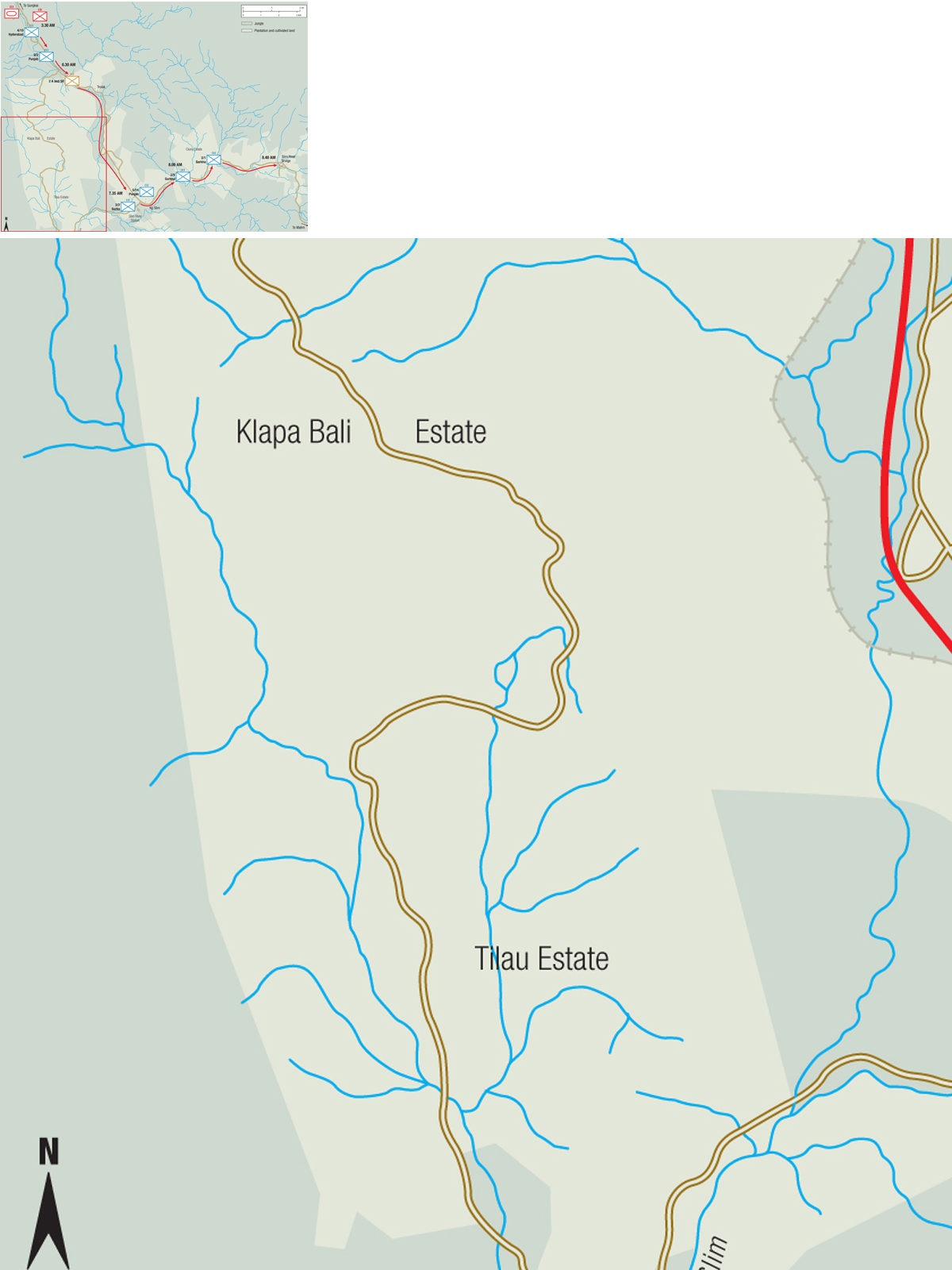

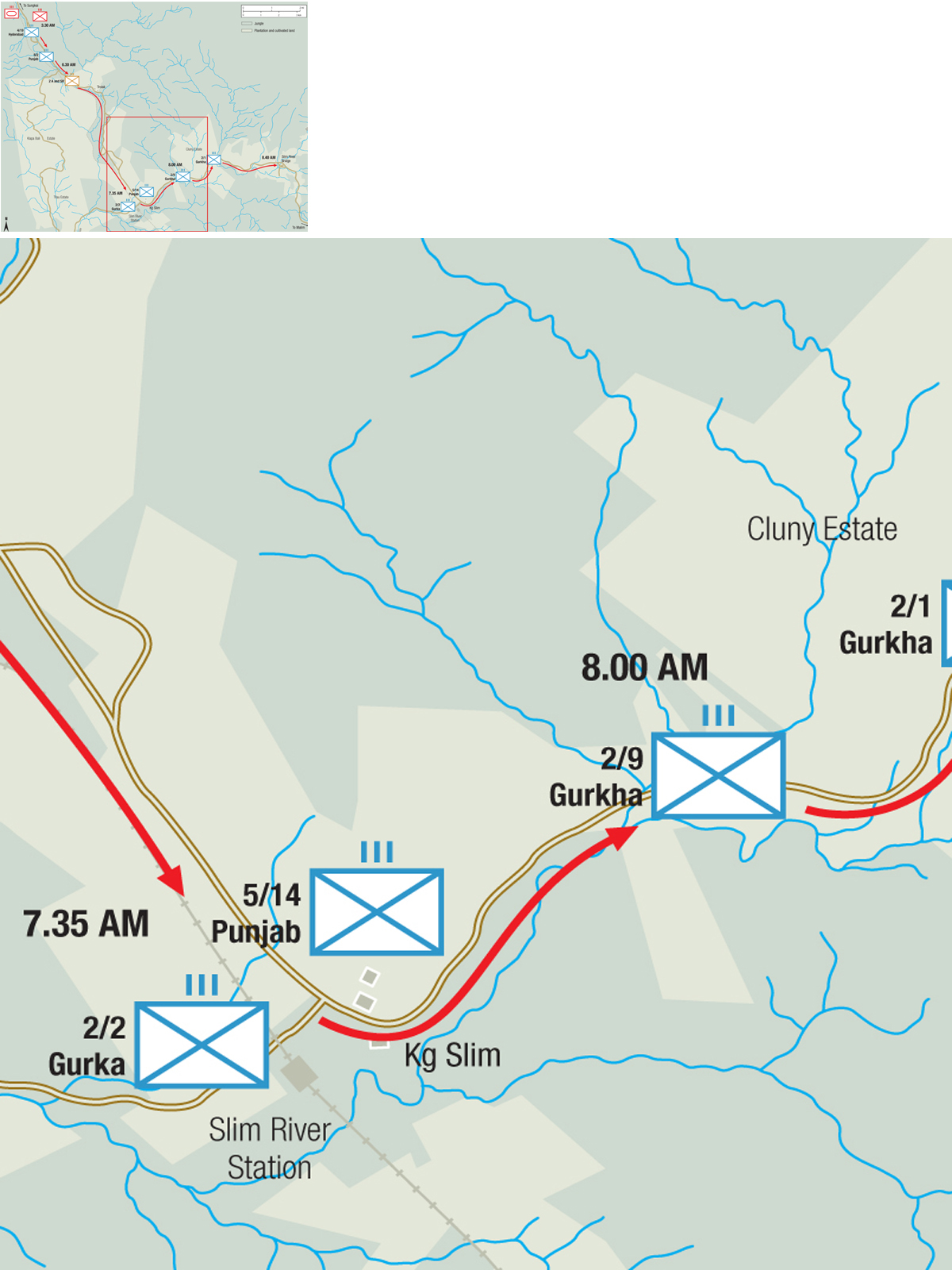

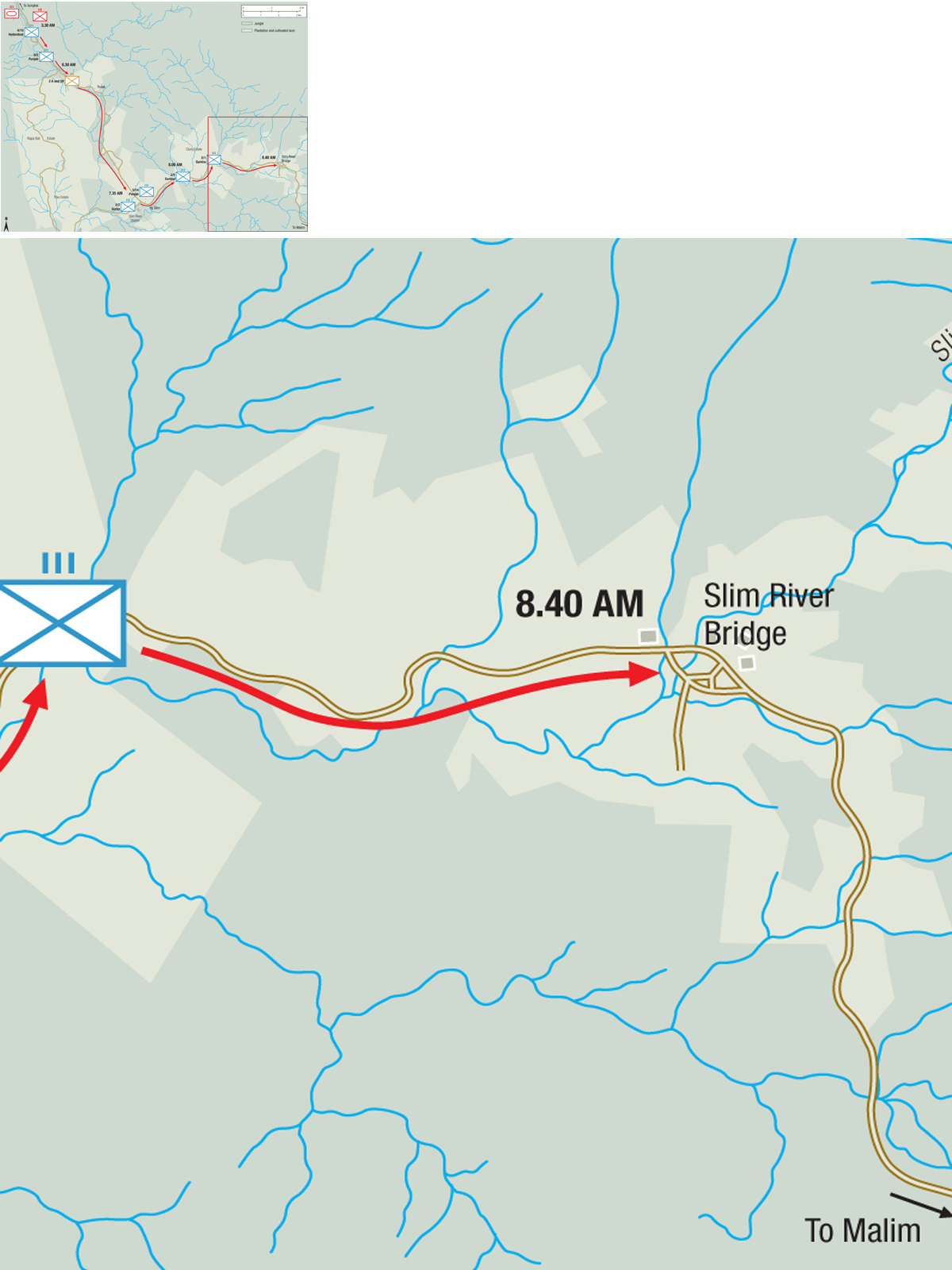

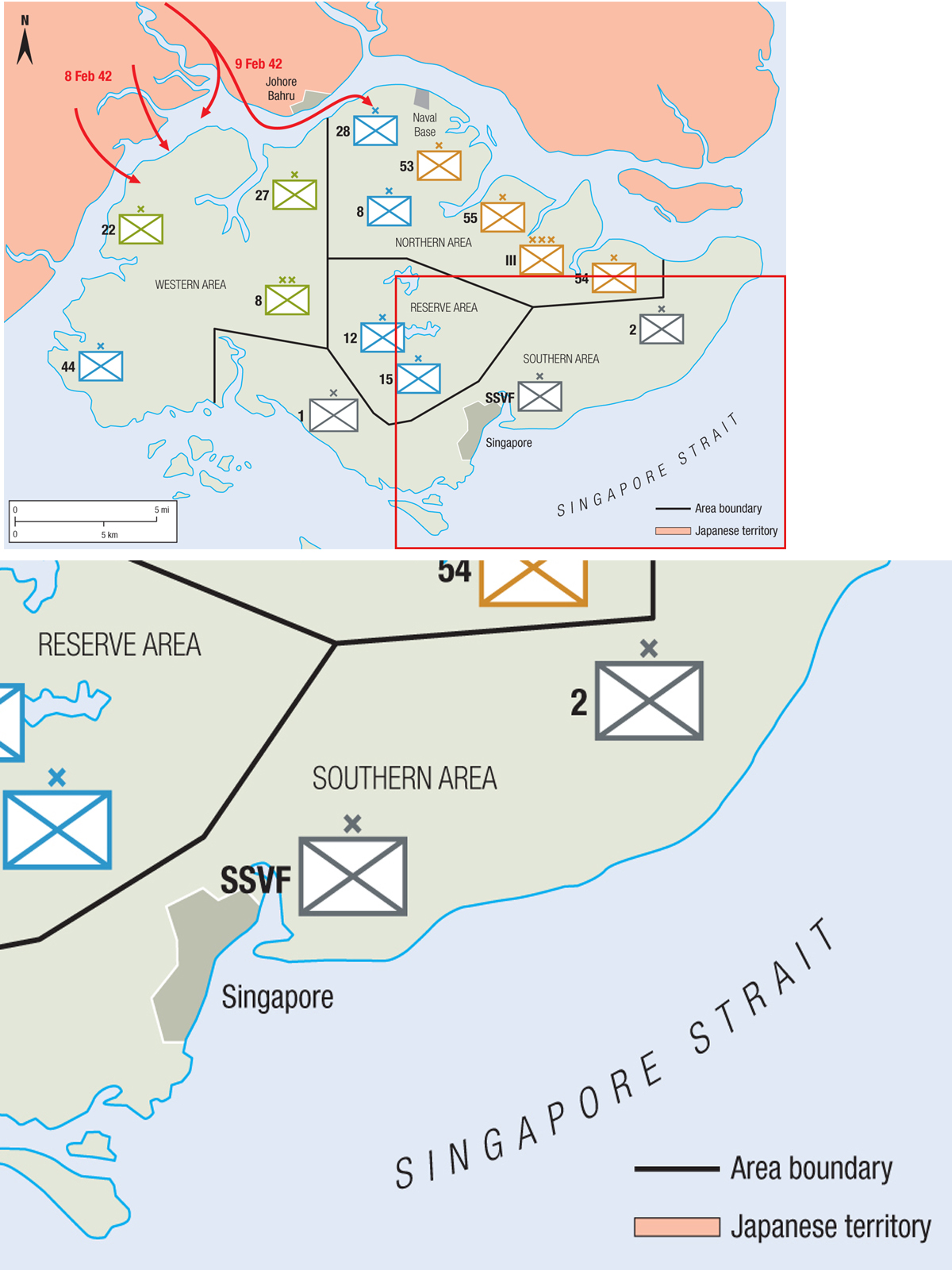

The Battle of Slim River, 7 January 1942. The Japanese armoured column’s movements are shown in red, together with the time of arrival at key points.

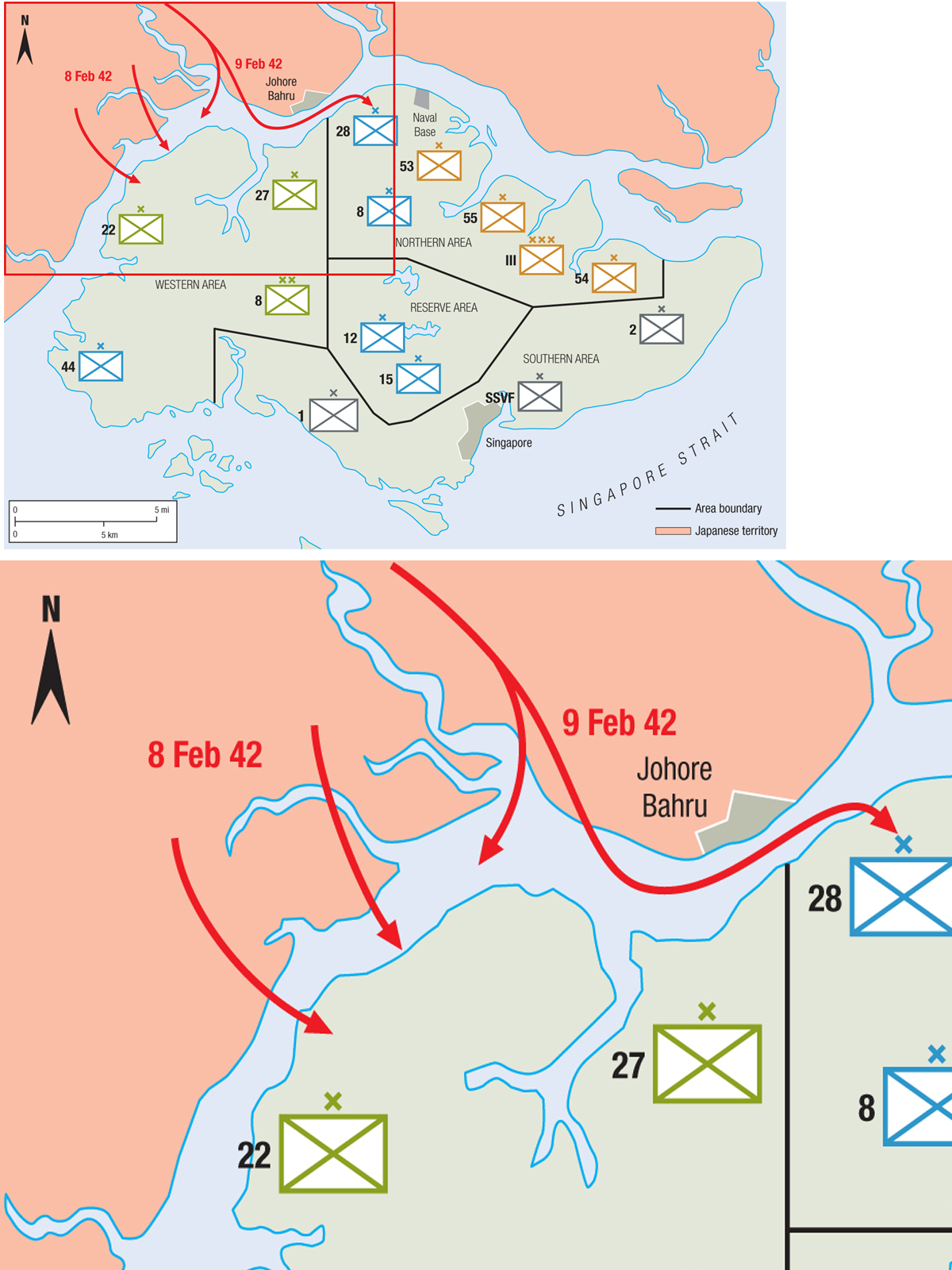

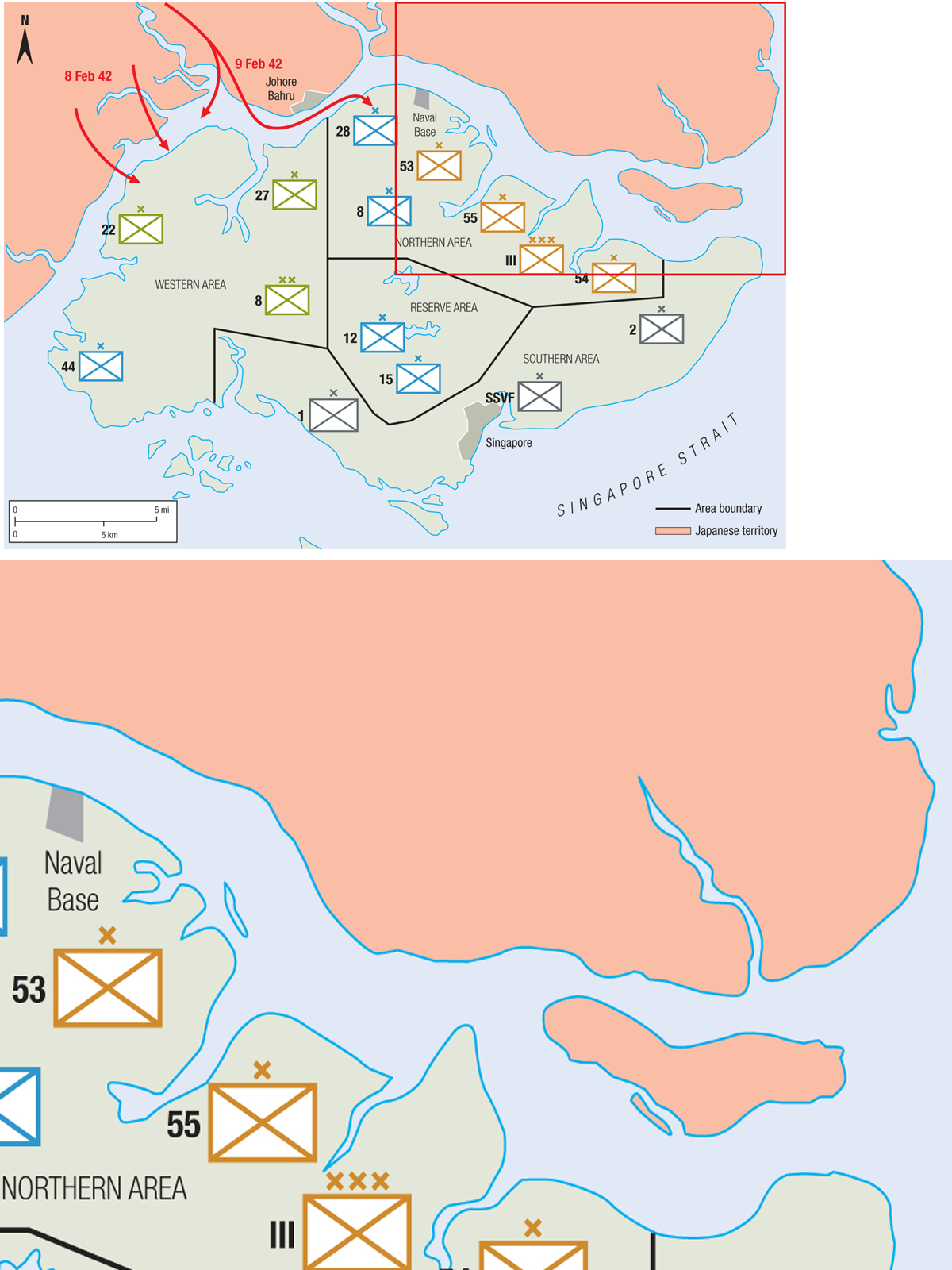

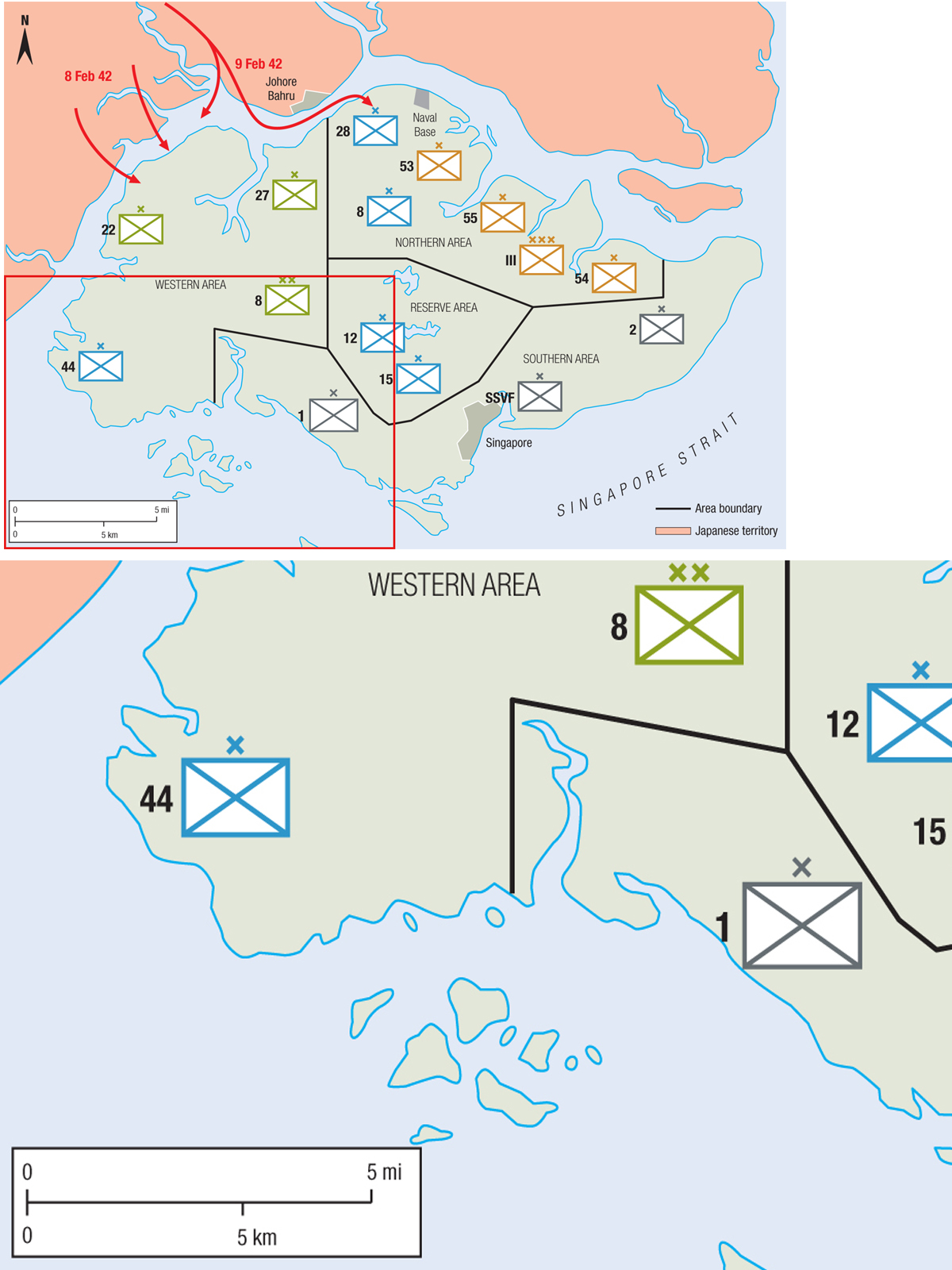

Dispositions of the British and Commonwealth forces on Singapore Island, 8 February 1942.

The bridge and road over Slim River. It is still straightforward to tour the action at Slim River; the bridge at Trojak is still intact, and a sign for the Cluny Estate and the bridge over Slim River are clearly marked. The author recently undertook a battlefield tour using a map from the official history.

11th Indian Division’s formation badge was still in use in captivity, on the entrance to Changi prison, with the motto added beneath of Qui Ultime Melior Ridet (he who laughs last, laughs best).

The first major land engagement of the Malayan campaign was the Battle of Jitra on 11 December. The Japanese Army overran the fixed defences at Jitra in 14 hours using tanks, infiltration and encirclement, with demoralised defenders abandoning valuable equipment and supplies. These losses could not be made up and were particularly damaging as the division was the best equipped formation in Malaya. The fighting quickly revealed how badly organised, trained and equipped the division was for war in the jungle. Bewildered by the jungle and the Japanese, morale amongst the poorly trained Indian troops plummeted. In contrast, the confident battle hardened IJA appeared ‘at home’ in the jungle.

Some successful actions were fought by Commonwealth jungle-trained troops. The Argylls first action at the Battle of Grik Road on 19 December showed the importance of jungle training in Malaya. The Argylls defended in depth and undertook aggressive encircling patrols. When they took Sumpitan, the battalion had advanced 36 miles in five hours. It was noted that when the Japanese were attacked, they bunched together. When the Argylls finally had to withdraw due to the weight of Japanese forces, it was again a fighting withdrawal using ambushes and encirclement.

The division became so depleted due to the heavy losses sustained during the retreat from Northern Malaya that the division was forced to amalgamate four units to form two battalions. The 2/9th Jats and the 1/8th Punjabis became the Jat/Punjab Battalion and on 22 December 1941 the 1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment and the 2nd East Surrey Regiment became the British Battalion.

Heath was educated at Wellington, where he acquired the nickname ‘Piggy’, and joined the 19th Punjab Regiment in the Indian Army in 1906. He was attached to the King’s African Rifles from 1907–14. He served with the 59th Scinde Rifles in the Mesopotamian campaign during World War I. He fought in the 1919 Afghanistan War and on the North-West Frontier commanding the 1st Battalion, 11th Sikh Regiment from 1929–33. He was appointed an instructor at the Senior Officers School, Belgaum from 1934–36 and then was commander of the Wana Brigade until 1939.

On the outbreak of World War II Heath was commander of the Deccan District. He was promoted to major-general and was given command of 5th Indian Division. He was made lieutenant-general in 1941 and given command of III Corps in Malaya. He was captured at the fall of Singapore and was imprisoned in Changi, Formosa

The division was bolstered by the jungle-trained 12th and 28th Indian Infantry brigades at the Battle of Slim River on 7 January, but once again tanks were a decisive factor, and decimated both brigades. In this case, Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart, appointed to command 12th Indian Infantry Brigade on 24 December, did not employ the correct tactics; because of bad positioning and the lack of anti-tank weapons and mines, his exhausted and depleted brigade could not prevent the Japanese from smashing right through it. It should be noted, though, that the brigade had been in continuous action for three weeks. Stewart’s tactics of filleting had been shown to be successful, but on this occasion their success had been demonstrated by the enemy. This defeat meant that the Japanese were able to take Kuala Lumpur unopposed. 11th Indian Division had been destroyed and General Wavell ordered Percival to bring the remnants back to Johore.

The Japanese reached Johore Bahru at the foot of the Malay peninsula on 31 January 1942. Fittingly, the last troops over the causeway were the pipers of the Argylls. The remaining uncommitted reinforcements on Singapore Island were 44th Indian Infantry Brigade, part of the recently formed 17th Indian Division; Indian and Australian reinforcements who had arrived between 22 and 24 January; and the rest of 18th Division, which had landed in late January. All these troops needed training (some even basic training) and they had no chance to acclimatise. They were nevertheless deployed in the front line of coastal defence. III Indian Corps took over the northern area; the Australians were on the west of the island with 44th Indian Infantry Brigade and the Singapore Fortress troops under Major-General Keith Simmons, consisting of the two Malaya Infantry brigades and the Singapore Straits Volunteer Force. The only reserve forces were the remnants of 12th and 15th Indian Infantry brigades.

Under heavy artillery cover, the Japanese attacked the Australian forces on 10 February and slowly advanced on the island. In the wake of a breakdown of communications, a shortage of water, fuel and ammunition, and general chaos, General Percival surrendered on 15 February. The defence of Singapore had lasted just 15 days, finally crumbling when the Japanese captured the water supply. The defeat was the worst in British military history.

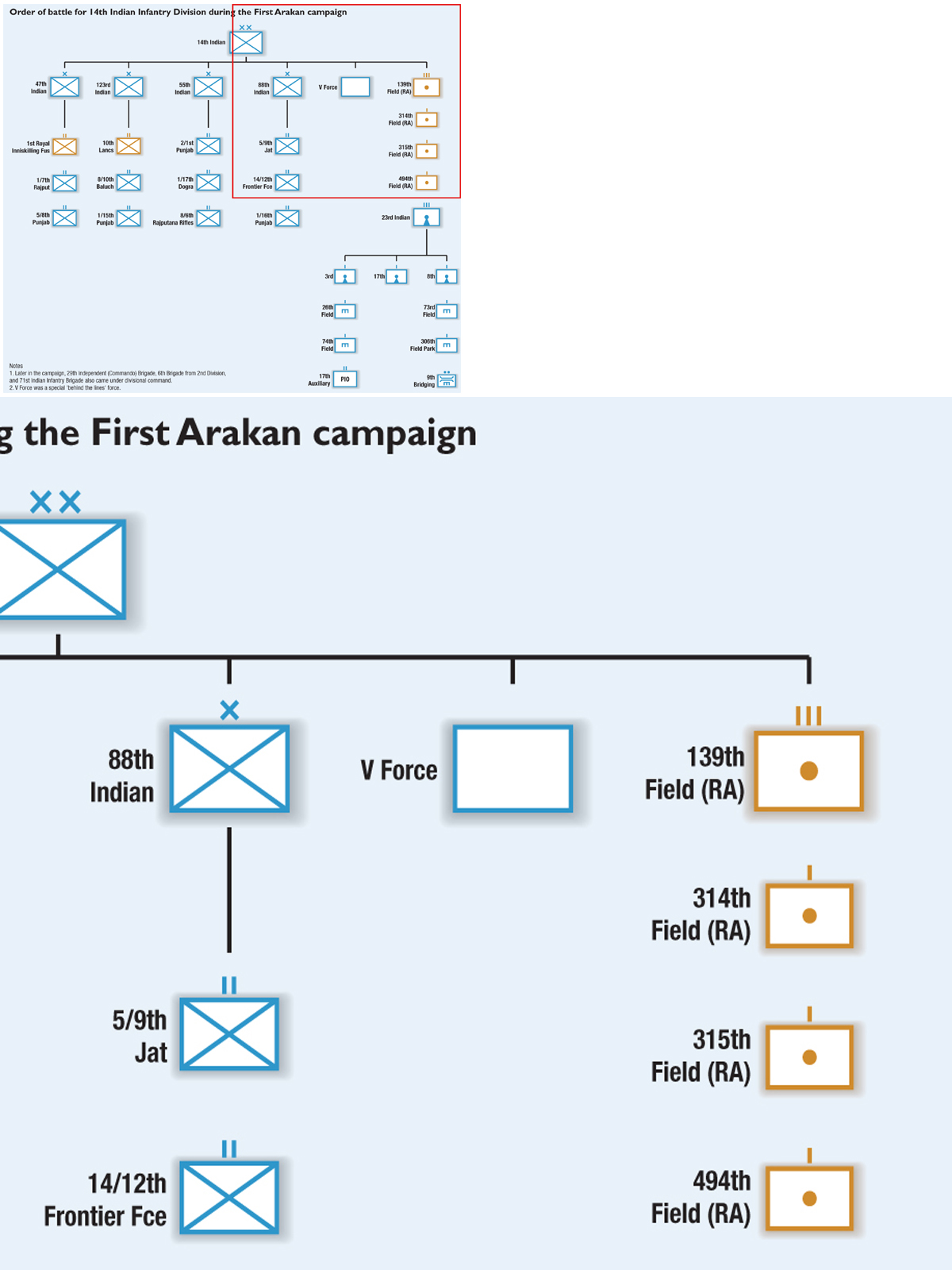

14th Indian Division began training for jungle warfare in Eastern Bengal. On his arrival back in India after the retreat from Burma, Major A.D. Firth was ordered to establish and operate a Jungle Warfare School at Comilla for the division, together with Major Robin Parry. Its syllabus covered six key areas: the use of the ‘hook’ and outflanking movements; maintaining ground having been outflanked, in order to keep the initiative; useful minor tactics, such as ambushing; dispelling the myth of the impenetrable jungle; health discipline; and fitness.

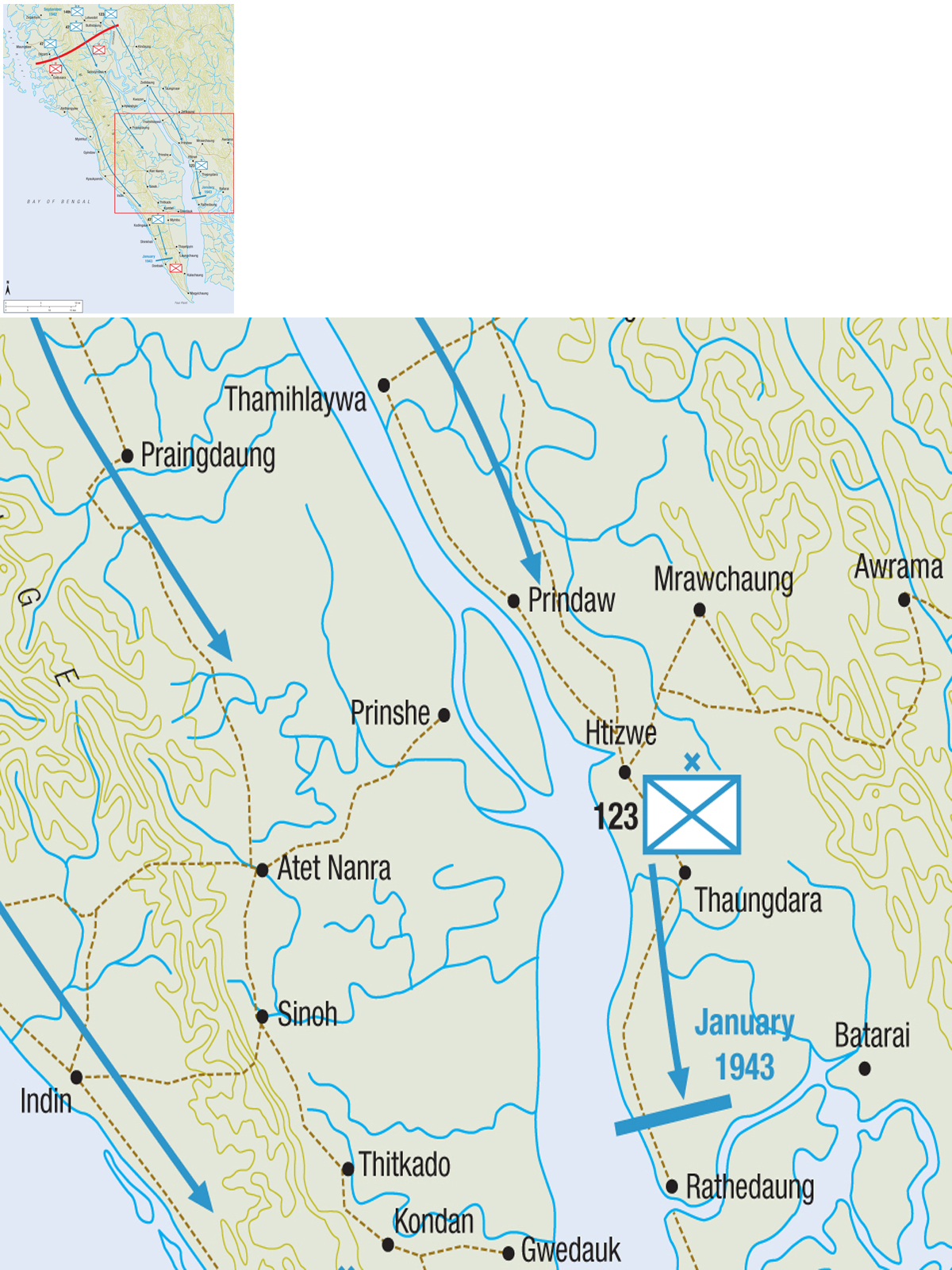

14th Indian Division’s attack at 1st Arakan, clearing the Mayu Peninsula.

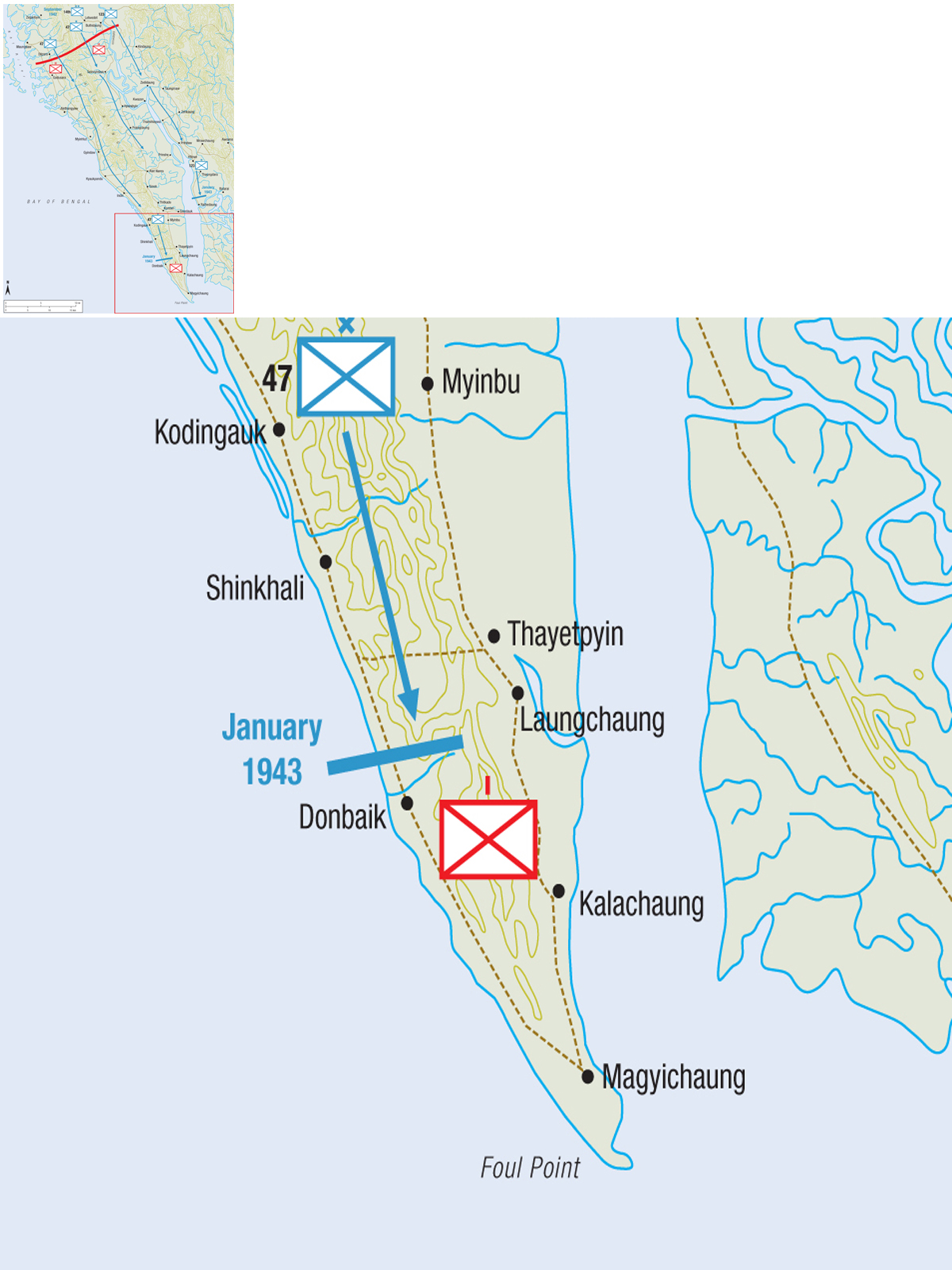

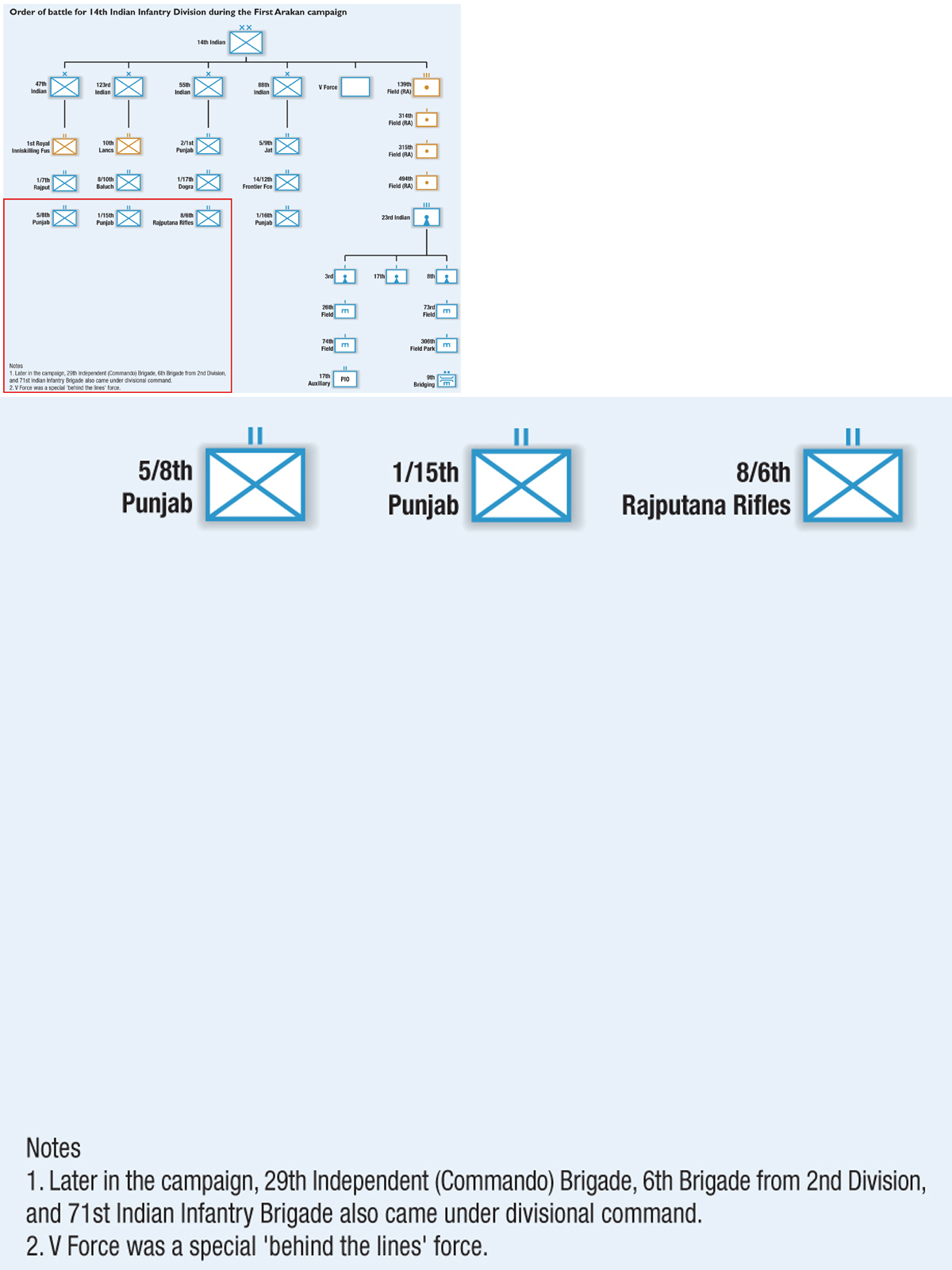

The cancellation of the amphibious ‘Anakim’ offensive to invade Burma and recapture Rangoon, prompted Wavell to mount a limited advance into the Arakan in late 1942. It initially involved 14th Indian Division clearing the Mayu Peninsula overland, whilst Akyab Island was captured by an amphibious attack mounted by the 29th Independent Brigade and 6th Brigade. The area chosen for the offensive consisted of a 90-mile long peninsula with the jungle-clad Mayu ridge along the centre, the Bay of Bengal on one side and the Mayu River on the other. The advance started on 21 September and a patrol of the 1/15th Punjabis quickly reached Buthidaung. Due to the lack of air cover, landing crew and the late arrival of 29th Independent Brigade, it was soon evident that the attack on Akyab would have to take place using only the 6th Brigade. The overland push by 14th Division was now the main part of the offensive, but progress was slow as the lines of communication needed considerable improvement.

14th Indian Division’s formation badge. The division was raised at Quetta in May 1941 by Major-General H.H. Rich. The central peak represents Mount Takatu, which overlooks Quetta, itself represented by the Q-shaped border of the badge.

The two Japanese battalions at the Maungdaw–Buthidaung line retreated with the build up of Indian forces, and thus the troops missed an opportunity of defeating a Japanese force. 47th Indian Infantry Brigade advanced down either side of the Mayu range and reached Donbaik in early January, whilst 123rd Indian Infantry Brigade headed for Rathedaung. The slow advance was not only dictated by the supply lines, but also the fear of exposing any flanks to the enemy. Unfortunately it also allowed time for enemy reinforcements to arrive. On 7 January, a company of the 1st Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers reached Donbaik, now held by one Japanese company, and attacked the position unsuccessfully. Then the whole battalion, with field and mountain artillery, failed in another attempt over the next two days. Similarly, the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers and 1/15th Punjabis also failed in their attack on Rathedaung. A series of abortive attacks on both positions was made over the next two months with increasing strength. These were the first encounters with Japanese defensive bunkers.

On 18 January, two battalions attacked the fortified position at Donbaik and failed. 55th Indian Infantry Brigade relieved 47th Indian Infantry Brigade and on 1 February the whole formation, plus eight Valentine tanks, an additional one and a half batteries and a light anti-aircraft battery attacked the position. Once again the attack failed, partly as a result of the tanks having only arrived the night before with no training between the tanks and the infantry, and partly because three of the tanks ditched at the beginning of the assault. Artillery support was inadequate as neither rolling barrages nor smoke screens worked; the Japanese were too well dug in. There was, moreover, little co-operation between the two arms of service. Infantry attacks often started late and therefore did not take full advantage of the covering artillery fire, giving the Japanese time to man their fire positions to repel the attacks.

All attempts by 14th Indian Division to break the enemy defences had failed. The abortive attacks on Donbaik and Rathedaung brought time for the Japanese to mount a counter-offensive. In stark contrast, the Japanese managed to clear the Kaladan Valley and both the east and west flanks of the Mayu range; combined with encircling attacks on Rathedaung and Donbaik, all within a month, this pushed back the numerically superior Commonwealth troops in demoralising confusion. By March morale was generally low, with some units such as the 1/15th Punjab Regiment and the Lancashire Fusiliers having been in continuous action for five months.

In June 1943, 14th Indian Division was re-designated as a training division as part of the reforms recommended by the Infantry Committee. The division was based at Chhindwara in modern-day Madhya Pradesh. It was surrounded by jungle and the climate was comparatively mild, which meant that training could continue all year round. All arms, not just infantry, underwent jungle training, as it was such an alien environment to every soldier: British gunners, engineers and signallers were all trained at Chhindwara. The emphasis was on individual and section training for the infantry, whereas the other arms concentrated on weapons training. Recruits, including officers and NCOs, were trained at section and platoon level by a representative training battalion from their regiment within the two training divisions. This was an extension of the Indian Army practice of using training battalions in a regiment but for a specific terrain and type of warfare. The regimental training battalions had been instituted in 1921 as a permanent depot with one training company for each of the battalions in the regiment.

The division was commanded by Major-General ‘Tiger’ Curtis, who had served in both the retreat from Burma and the First Arakan. Only a handful of officers in the division had battle experience against the Japanese. Some instructors were sent from serving battalions, but units rarely sent their best men and, as it took three months to train the instructors, they were not the ‘finished article’ by the time the first intake arrived.

Training was intensive, for nine hours a day, six days a week, and often including three nights’ work a week. Recruits spent the first month in the camp training in battle drill, field movement and weapons training. Range safety was lessoned, though no accidents resulted and this helped to achieve realism. Similarly, in order to match the Japanese efficiency with the mortar, units were trained to concentrate their fire. The second month involved training in the jungle, making and living in bashas (shelters made out of bamboo), with numerous exercises using live ammunition. One exercise that helped introduce the troops to the noise of battle and accustom them to the supporting arms involved troops advancing 250 yards towards an enemy held nullah. Artillery support came from 25-pdrs with medium machine-gun fire from the flanks. Once they had reached the enemy lines explosive charges were set off to simulate enemy artillery and support for a counter-attack. In all the exercises, there was strict discipline. Silence was maintained at all times, no litter was dropped and all ranks were stripped to the waist to aid acclimatisation, earning the division the nickname ‘The Bareback Division’. There were long patrols of between 36 and 48 hours and leaders were responsible for their troops’ administrative needs and anti-malarial discipline. Jitter parties were organised using likely Japanese ruses. Swimming lessons were encouraged as few Indians, and even fewer Gurkhas, could swim. At the end of the two months, the trainees were expected to march 25 miles a day with full equipment.

There were visits from serving officers to lecture on operational lessons from Burma and other specialists such as Jim Corbett, an expert in tracking and killing man-eating tigers in the Indian jungles. He was made a lieutenant-colonel with a commission to instruct jungle lore to the men of both training divisions. His book Man-Eaters of Kumaon was recommended reading in the training division and was translated into Roman Urdu by GHQ India. It described some of Corbett’s experiences of tracking down tigers in the jungle. It was thought that valuable lessons of jungle lore could be learnt and then applied to operations against the Japanese.

The division had started taking recruits by the beginning of December 1943. 14th Indian Division made an important contribution to the ultimate defeat of the Japanese in Burma; the 16th (Training) Battalion the Punjab Regiment, part of 55th Infantry Brigade within the division, sent 1,957 trained soldiers to the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 14th and 15th battalions of the regiment.

David Tennant ‘Punch’ Cowan (1896–1983), commander of 17th Indian Division between 2 March 1942 and 22 June 1945. Cowan was Deputy DMT at GHQ India in 1941 and then DMT, until taking up the post of divisional commander.

The 17th Indian Division was raised at Ahmednagar in June 1941. It was originally earmarked for the Middle East and began training at Dhond. The division’s standard of general training was low, even before it was sent to Burma. In December 1941, Brigadier ‘Punch’ Cowan, officiating as Director of Military Training (DMT), had agreed with the divisional commander, Major-General Sir John Smyth VC, that the division needed a further six weeks’ training once it had arrived in Iraq, where it was originally destined. Two of its brigades, the 44th and 45th, were nevertheless sent to Malaya as the military situation deteriorated. Thus, all that was sent to Burma of the original division was one brigade (the 46th) and the Divisional HQ. The little specialised instruction it had undertaken was confined to mechanised desert warfare, which was unsuitable for fighting in Burma. Although 17th Indian Division was strengthened after war broke out by the attachment of 16th and 48th brigades, and 2nd Burma Brigade, very little jungle training had been undertaken by the incoming troops and the formation was not a fully integrated fighting force.

On 20 January 1942 the Japanese 15th Army, comprising 33rd and 55th divisions, invaded Burma. As in Malaya, the Japanese seized and maintained the initiative in the jungle, particularly as the Commonwealth troops were equipped with motor transport and therefore were tied to the roads and continually out-flanked in the jungle. The GOC Burma, Lieutenant-General Thomas Hutton, wanted to keep the enemy as far away from Rangoon as possible, and chose a strategy of small pockets of defensive troops rather than concentrating his forces. The defending force was 16th Indian Infantry Brigade based at Kawkareik. The formation had now undergone some jungle warfare training but this was half-hearted as there was little direction on the subject. The Japanese pushed the brigade back from the Dawnas to Kawlareik in less than 48 hours and the defending troops were in disarray. The Japanese went on to infiltrate the Moulmein area and put in an unsuccessful attack on the morning of 30 January. Another attack in the afternoon was also repulsed, but the 7th Burma Rifles collapsed and the combined pressure of the Japanese attack and infiltration meant that a withdrawal was inevitable.

The original 17th Indian Division formation badge featured a streak of lightning, but after the Japanese radio propagandist, Tokyo Rose, had called it ‘the division whose sign is a yellow streak’, and it had been driven out of Burma, the ‘lucky’ black cat was adopted. The adoption took place in 1943.

In addition, the unreliability of the Burma Rifles was a huge source of concern. The divisional commander, Major-General Smyth, wanted to use them in their usual role of irregular troops and for reconnaissance. However, this was deemed to undermine the prestige of the Burma Rifles. Instead, the Burma Rifles battalions fought as regular units, and fought poorly as a result. The Japanese seized the initiative in these early stages of the campaign forcing the British to retreat from a series of positions back towards Rangoon, despite pleas from High Command to mount a forward defence.

The bridge over the River Sittang was of vital importance to both the Japanese and the Allies; it was only 100 miles from Rangoon, and was a vital supply link both for the Burma Road to China and for reinforcements and supplies for the Burma campaign. Generals Wavell and Hutton thought it best to keep as much distance between the enemy and Rangoon. As a result Smyth was refused permission to withdraw early to the bridge to build up a defensive position to the west, which was unfortunate since the ground was suitable for open warfare, and the 17th Indian Division had been trained in this. Thus, when the troops did retreat to the Sittang Bridge, there was no time to create a defensive position and the Japanese were able to cut in behind the main body of the division. Although the bridge was held for as long as possible by units of the 48th Indian Brigade, the decision to blow the bridge before all the Allied forces were across was taken by the brigade commander, Brigadier Noel Hugh-Jones; this was done in consultation with Smyth, who knew that his other two brigades were still fighting on the wrong side of the bridge. Most of the Gurkhas, unlike the British, could not swim, so there were large numbers of Gurkha casualties, with many taken prisoner by the Japanese. The Sittang Bridge disaster sealed the fate of the defending forces. The 17th Division was reduced to 1,420 rifles, 56 Bren guns and 68 Thompson sub-machine guns. The division had to be reorganised after Sittang with some battalions amalgamating. Major-General D.T. ‘Punch’ Cowan took over command of the division on 2 March 1942.

The defence of Rangoon was now unfeasible due to the lack of troops and equipment. The army in Burma received further reinforcements, but they were mainly untrained. The exception was the battle hardened and well-equipped 7th Armoured Brigade, which arrived fresh from the Western Desert to shore up the defences. Little alternative now remained other than retreating northwards to Mandalay. On 16 March, General ‘Bill’ Slim was appointed corps commander of Burcorps, and realised that his troops were ill-trained and ill-equipped for jungle warfare. He made an immediate impact on the officers under his command, noting that the ideas of the staff were not necessarily correct.

The division covered the retreat from the Fall of Rangoon to the borders of India. There were successful actions, such as that of 48th Brigade at Kokkogawa on 12 April which resulted in a significant reverse. The brigade commander, Brigadier Ronnie Cameron, had realised the importance of all-round defence in the jungle, and with artillery and tank support from 7th Armoured Brigade repelled the Japanese attacks for two days, allowing 1st Burma Division to escape out of the Yenangyaung trap. This showed that an efficient and well-trained formation could adapt to jungle warfare even after being in almost continuous action for months. The Army in Burma had no real chance of stopping the Japanese and suffered a string of defeats at the battles of Yenangyaung, Monywa and Shwegyin. The British and Commonwealth forces successfully withdrew to India when it became clear that no other alternative remained. It was the longest retreat in British military history.

The officers of 17th Indian Division realised that they had to learn from their recent experiences in Burma. Training was of vital importance for the new recruits that were drafted into the division. The importance of silence, learning to swim, patrolling and getting used to the jungle were emphasised. As the first divisional training instruction noted in June 1942, the training had to be realistic. A second training instruction, issued the same month, stated that there was enough jungle training literature (including the division’s own Cameron Report), and the division just had to ‘get on with it’. The division reorganised as a light division on a jeep and pack basis.

The division fought at Imphal, took Meiktila and held it against heavy counter-attacks, and then embarked on the road to Rangoon to be present at the retaking of the city. The division covered 725 miles in three months and accounted for 10,263 enemy killed, 167 captured, 212 guns and 15 tanks destroyed. It fought longer against the Japanese than any other division and was often referred to by its troops as ‘God’s Own Division’.

General ‘Bill’ Slim driven by Major-General ‘Pete’ Rees, flanked by the troops of 19th Indian Division in Mandalay. Behind them in the jeep is Lieutenant-General Montagu Stopford, commander of XXXIII Indian Corps. (IWM SE 3530)

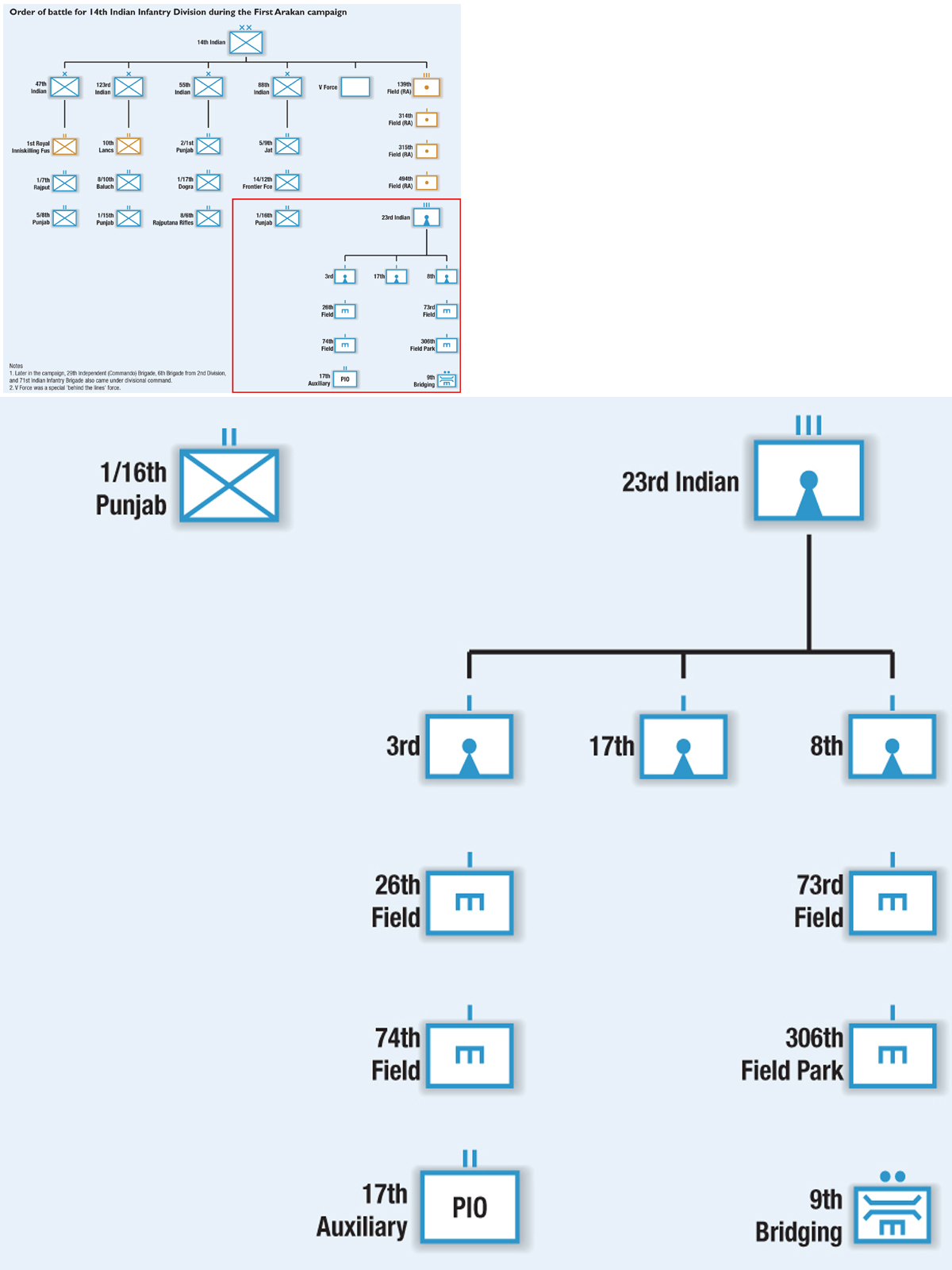

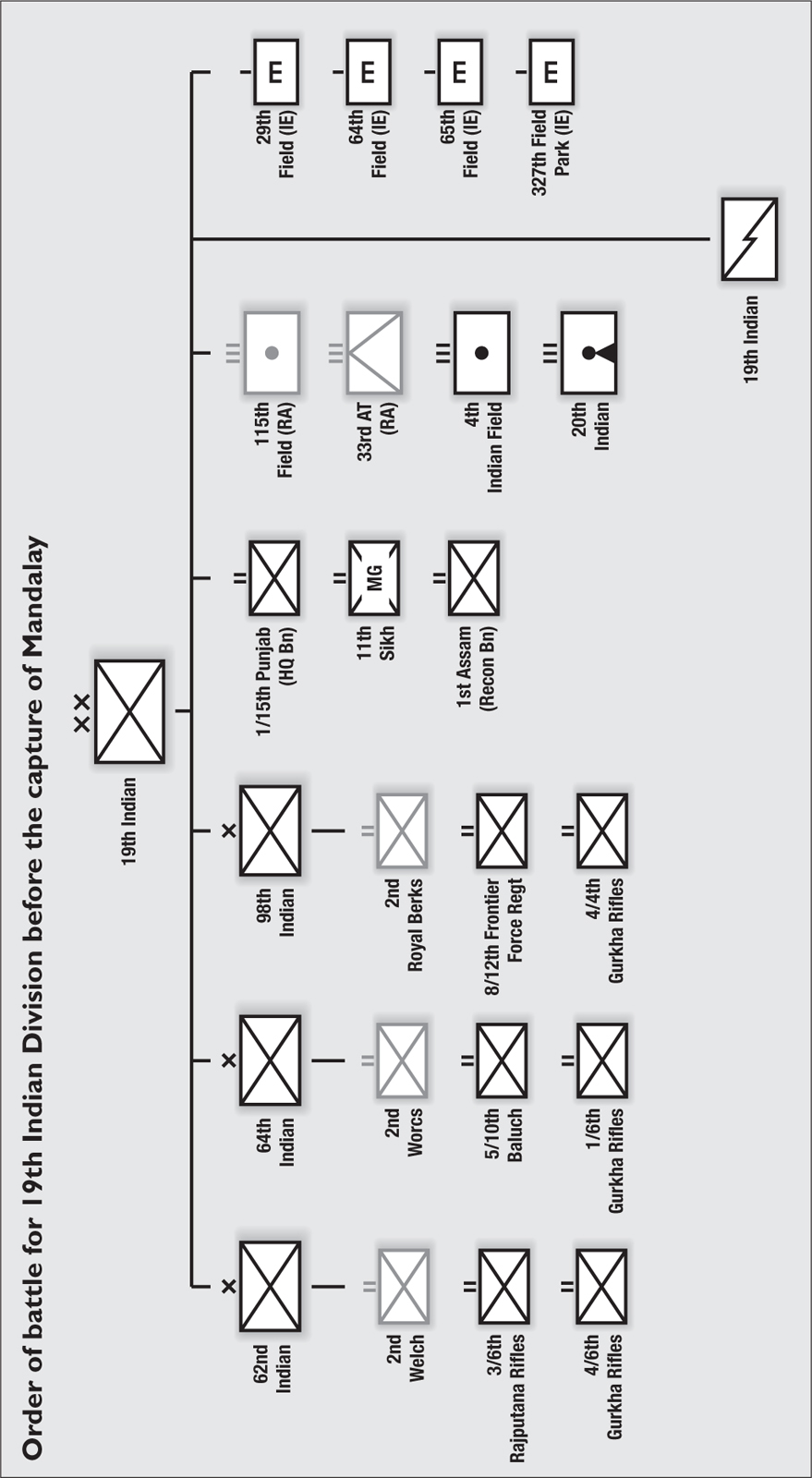

The 19th Indian Division was formed at Secunderabad on 1 October 1941, and along with 25th Indian Division defended Southern India in 1942. It underwent jungle training at Coimbatore, which was completed by December 1943.

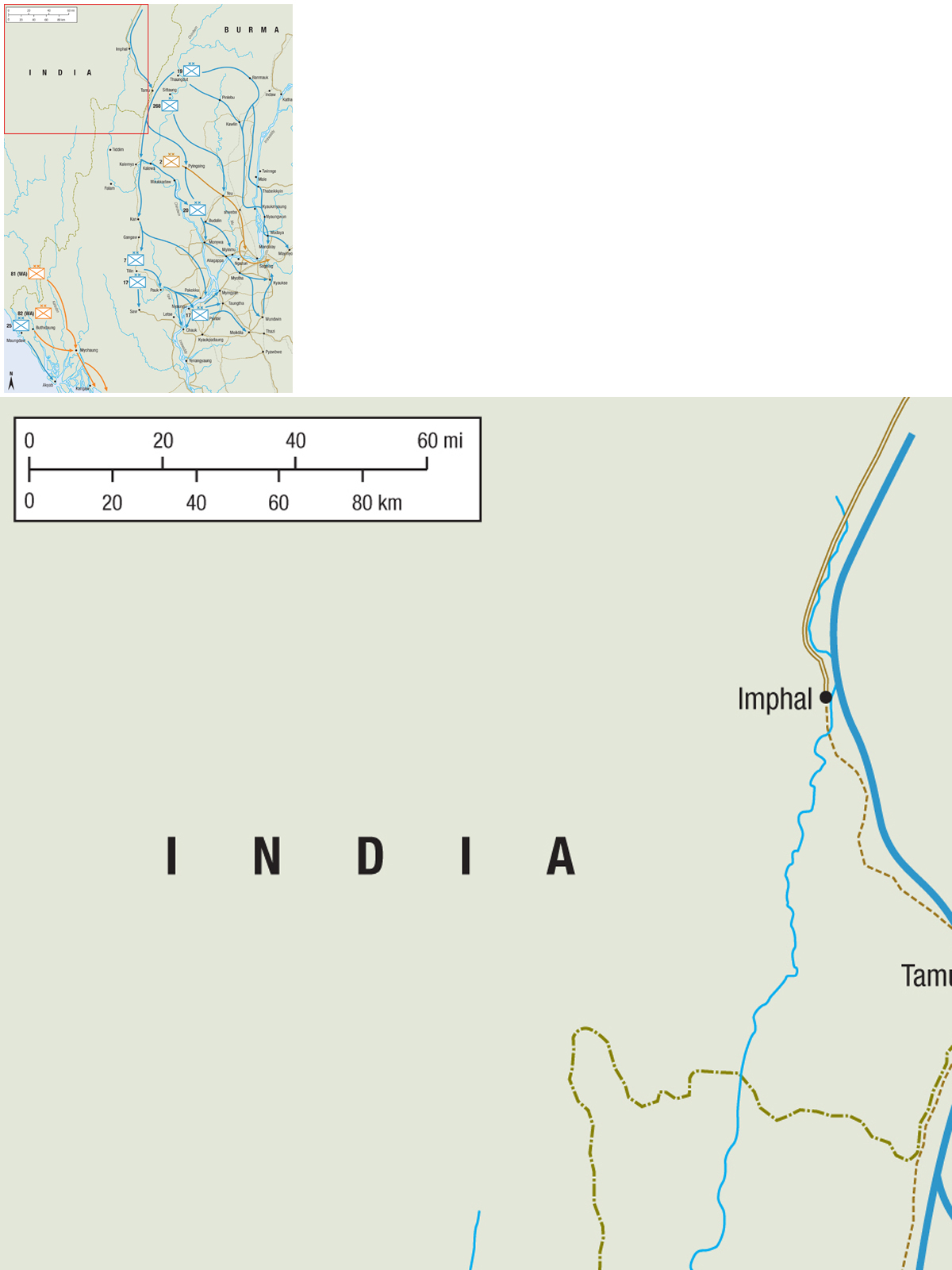

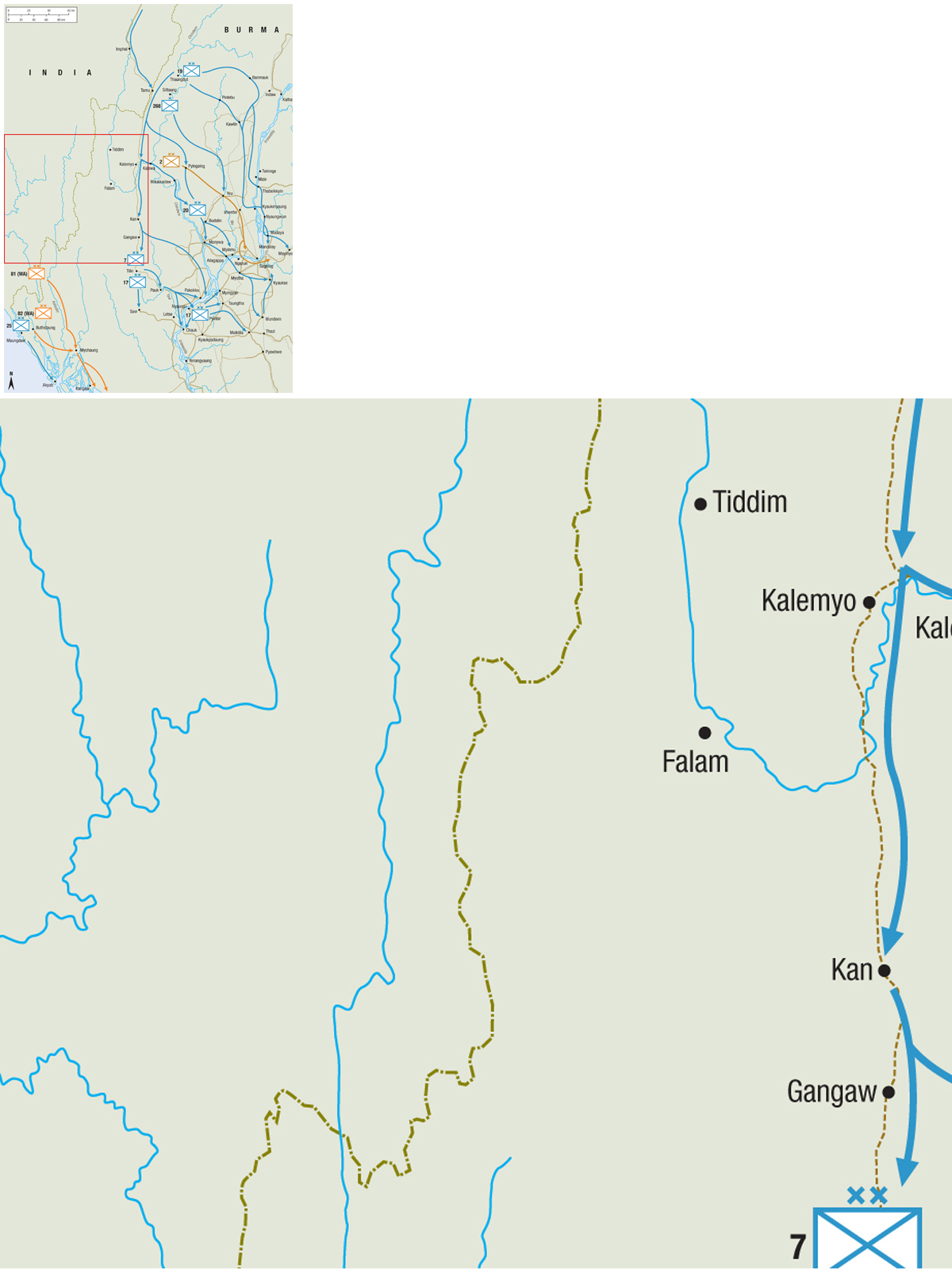

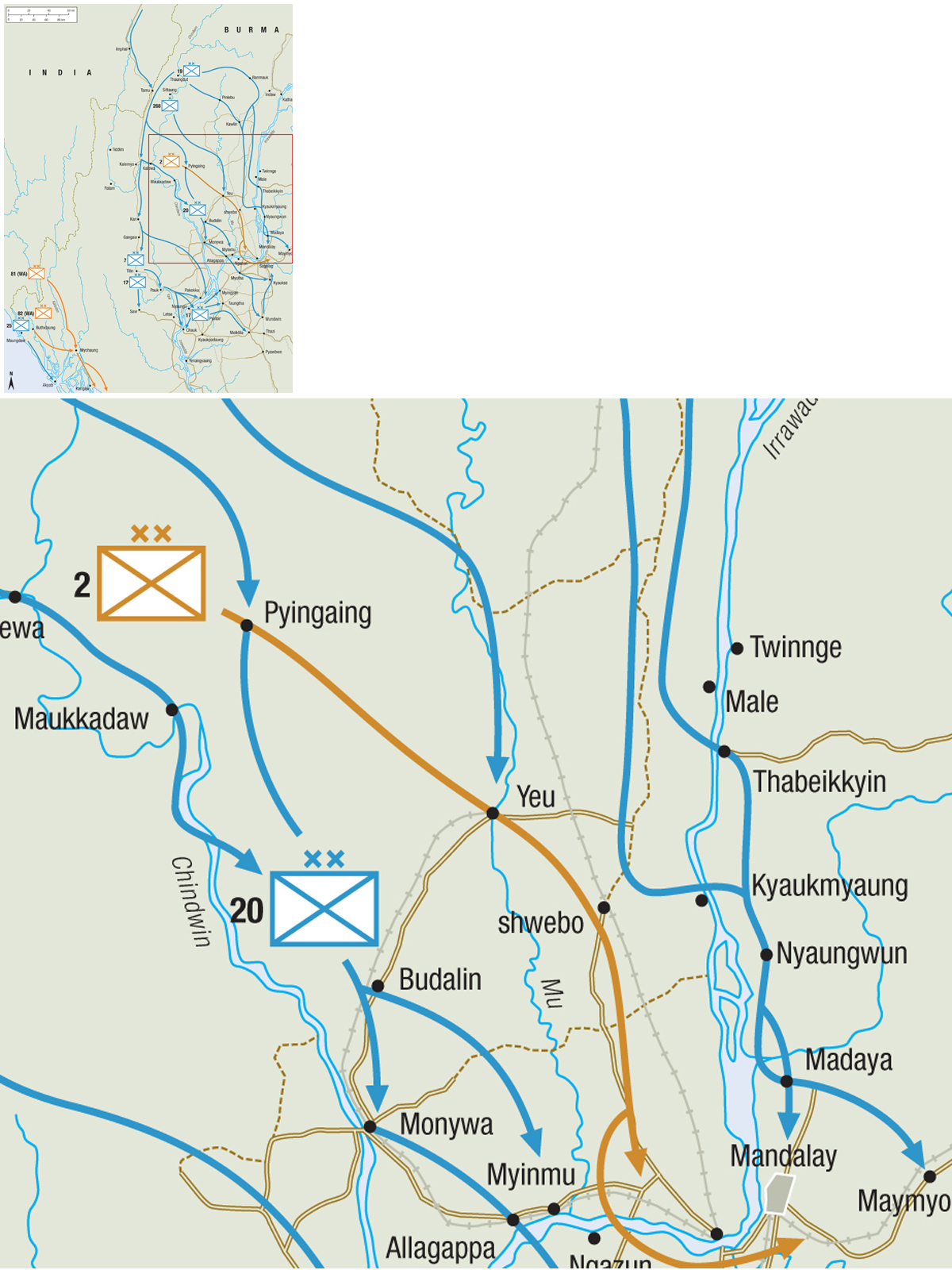

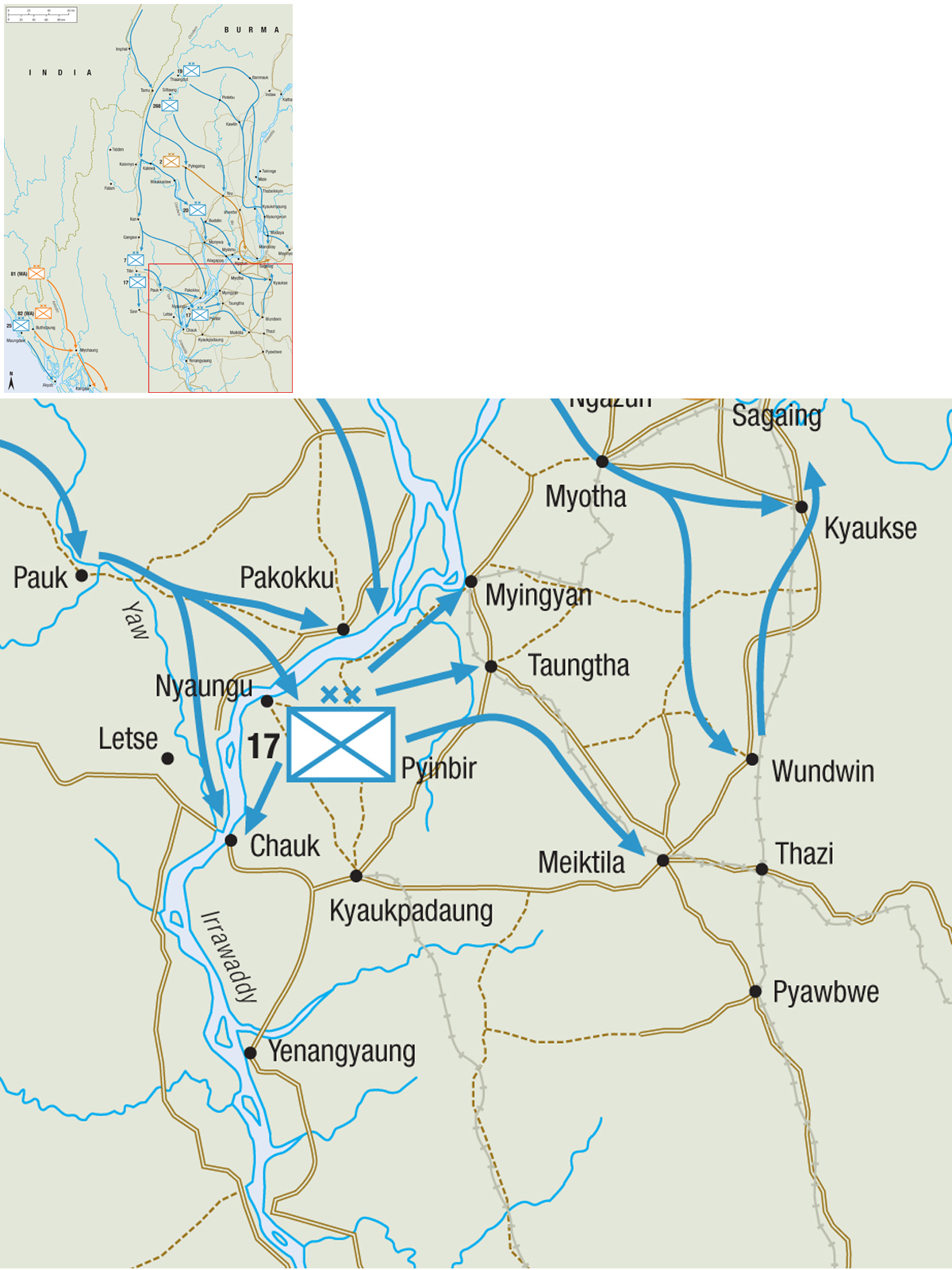

The first major action executed by the division was at the Battle of the Irrawaddy Crossing. This was part of Operation Extended Capital, the revised Operation Capital, whose aim was to destroy the Japanese army in Burma. The plan was for XXXIII Corps and 19th Indian Division to cross the Irrawaddy, north of Mandalay and then move towards the city. This diversion would give the impression to the Japanese army that IV Corps was still in the north and XXXIII Corps in the south. The rest of XXXIII Corps, namely 2nd British Division and 20th Indian Division, would cross at Ngazin and the whole corps would encircle Mandalay. The Japanese forces would then engage the bulk of their forces in the defence of Mandalay, whilst IV Corps would move south, cross at Nyaungu, and advance for Meiktila. This would give the major battle that the ‘manoeuvrist’ General Slim desired.

On 9 January 1944 men of the 2nd Battalion, the Welch Regiment were sent across the Irrawaddy at Thabeikkyn for reconnaissance. The division then crossed at Kyaukmyaung (46 miles north of Mandalay) using rubber assault boats. Two regiments from the division also established a bridgehead at Thabenkkyin, 20 miles to the north, as a diversion, making the enemy think that the northern bridgehead was to link up with 36th Division. Both bridgeheads were held against repeated Japanese counter-attacks for 20 days, and contained Japanese troops caught on the eastern side of the river, particularly at Kabwet. The troops also took two tactical features inland – Minbaung Taung ridge and Pear Hill – both of which were key observation posts.

After this initial success the divisional commander, Major-General ‘Pete’ Rees, drove the division straight for Mandalay down the Irrawaddy with the Shan mountains to the east, taking Tongyi and Madaya on the way. He then formed ‘Stiletto Force’ consisting of the Divisional Reconnaissance Battalion, 1/15th Punjab Regiment, along with British and Indian tanks, gunners and Madras Sappers. The force advanced along the side of the Irrawaddy and reached the north-west of Mandalay at 3 a.m. on 8 March, encountering little opposition along the way and surprising the Japanese defenders. The rest of the force came down the main road from Madaya, apart from a brigade, which took the hill station of Maymyo. After heavy fighting, Mandalay Hill and Fort Dufferin were taken on 20 March. Members of the division raised the Union Jack, the division flag and the regimental flag of the 1/15th Punjab Regiment on Fort Dufferin.

Thomas Wynford Rees was born in Barry in 1898. He served with the 125th Napier’s Rifles in Mesopotamia during World War I, where he was awarded a DSO and a Military Cross. He served in Waziristan in 1920, 1922–24 and 1936–38. From 1926–27 he was an instructor at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and afterwards took up the post of private secretary to the Governor of Burma.

On the outbreak of World War II, Rees was commanding the 3/6th Rajputana Rifles. He commanded 10th Indian Division for a short period before taking the command of 19th Indian Division in October 1942. To this division he was known as ‘Pete’, to the Welsh troops in the division ‘the Docker’, to the Indian troops ‘General Sahib Bahadur’ and to the 14th Army generally ‘Napoleon’.

Rees later commanded the 4th Indian Division and then the Punjab Boundary Force which was charged with the task of policing the creation of Pakistan and an independent India. His last post, before retirement in 1948, was the Head of the Military Emergency Staff to the Emergency Committee of the Cabinet in Delhi.

Operation Extended Capital and the capture of Mandalay, 19 December 1944–20 March 1945.

19th Indian Division’s formation badge; as a result the division became known as the ‘Dagger Division’. It was originally formed in India in 1941 under Major-General Sir John Smyth VC before he took over 17th Indian Division. The badge was designed and drawn by his wife, Frances. The dagger symbolised a readiness to strike against any attempted Japanese invasion in 1942.

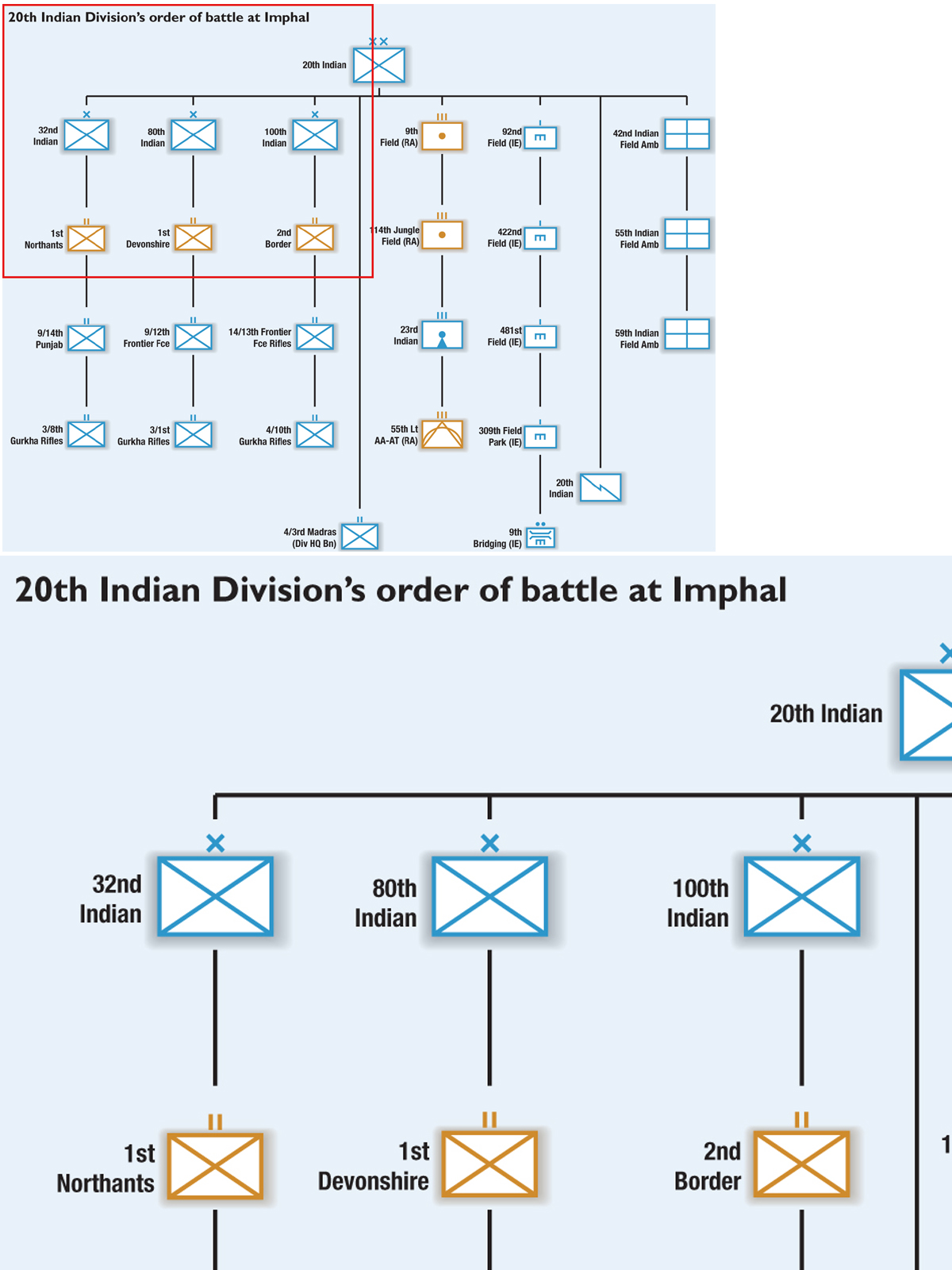

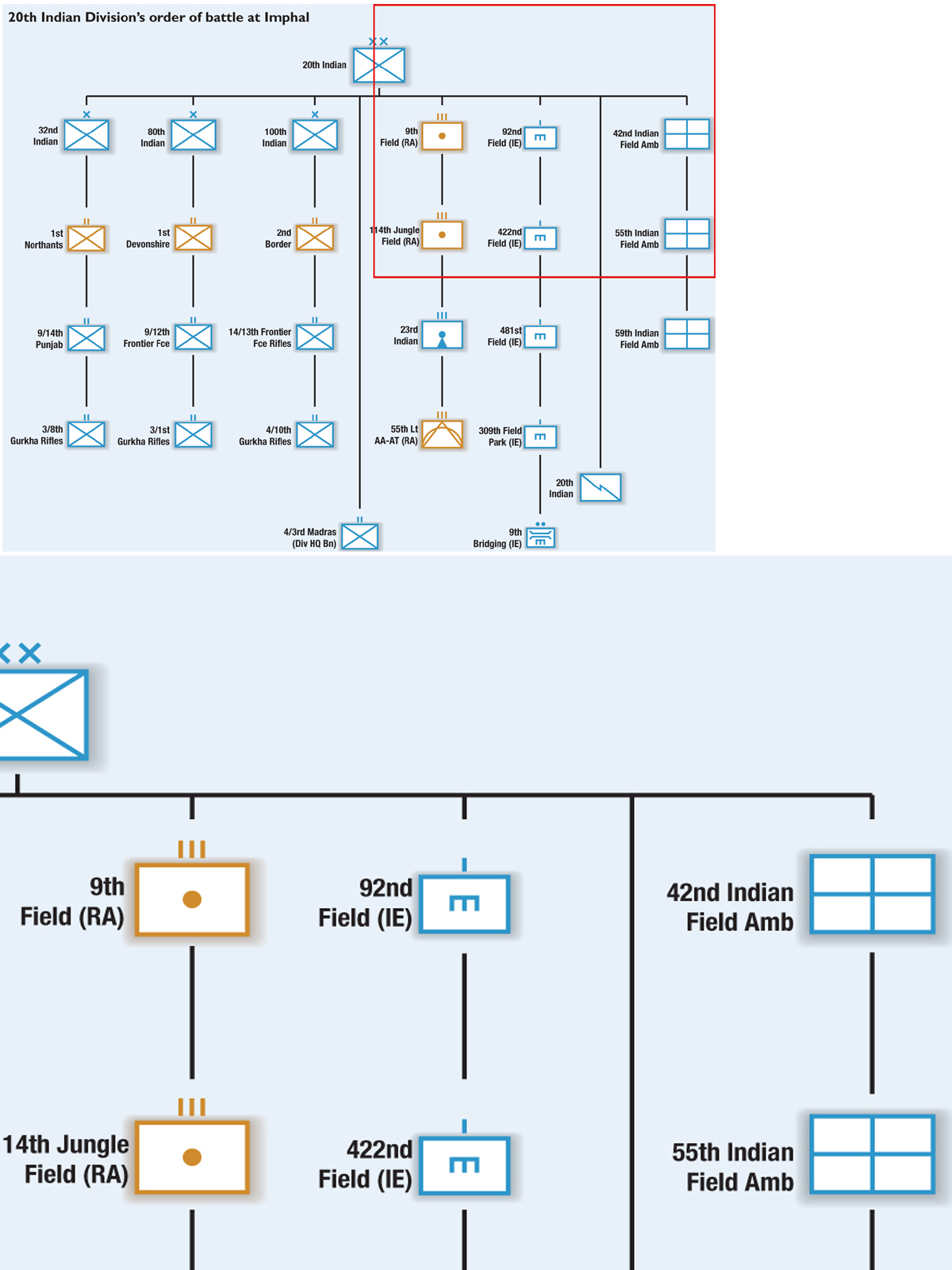

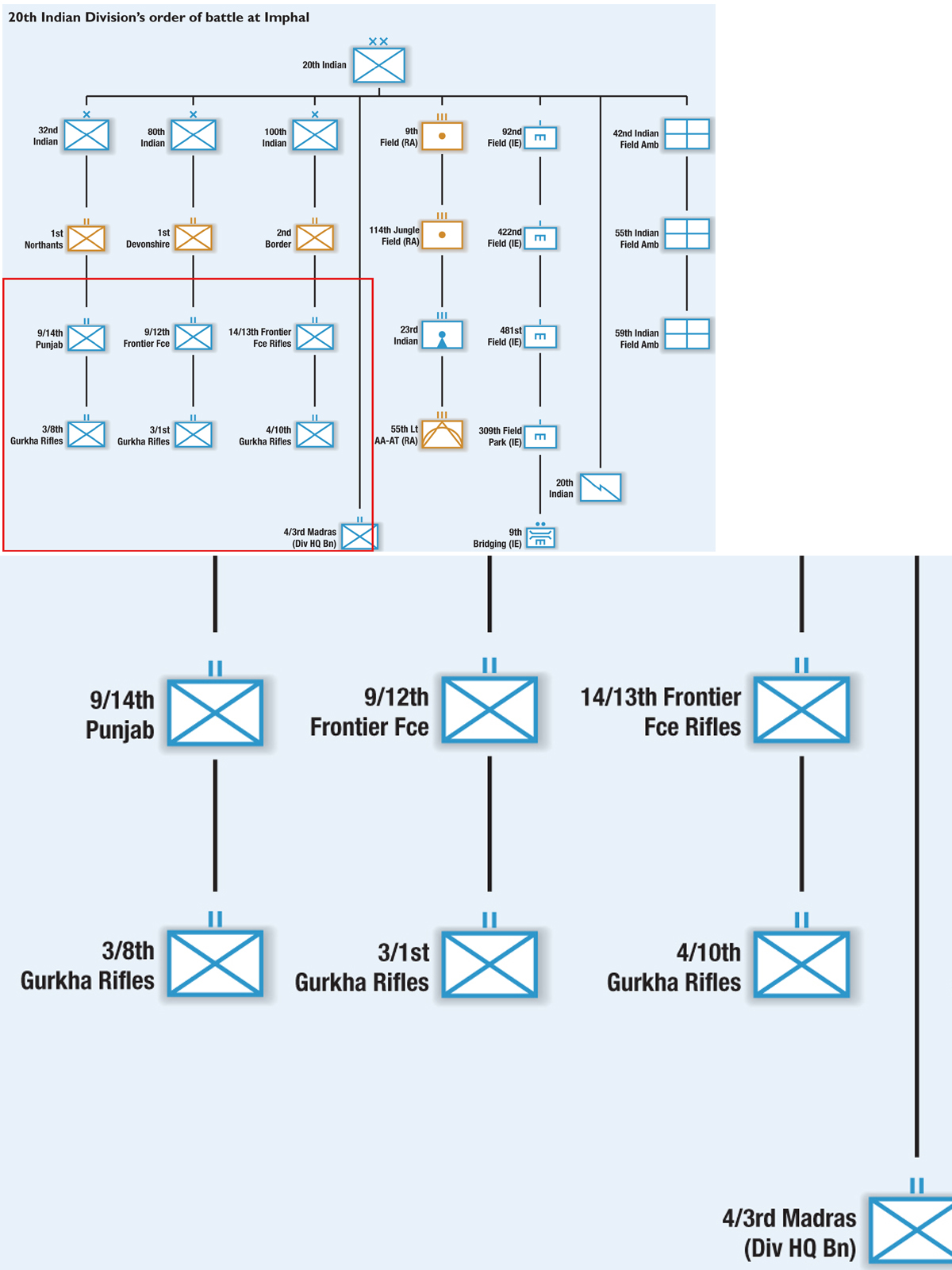

The 20th Indian Division was raised in Bangalore in March 1942. It was established and trained solely for the war in Burma. The GOC, Major-General Douglas Gracey, stationed in Ceylon, issued a training policy for his division in April 1942. It directed that all British officers, British other ranks, English-speaking Viceroy commissioned officers, and Indian other ranks should read the training pamphlets such as MTP No. 9 and Japanese Tactical Methods, the first training manual to deal with Japanese tactics and the defence against them, using examples from Malaya and the Philippines. Japanese Tactical Methods was first produced in Malaya in 1942 by Malaya Command. Gracey stressed the importance of reading the training pamphlets and using their ideas in training, and for them not to be regarded as ‘just another bit of bumph’. In an appendix to his memorandum for training troops in jungle warfare against Japanese forces, Gracey encouraged the constant handling and use of weapons, unorthodox tactics but strict discipline, and the use of booby traps and similar devices. Like other divisional commanders, Gracey wanted training to be realistic and undertaken by all soldiers in his division, including the Royal Indian Army Service Corps and the medical units. His training principles included: outflanking, encircling, attacking by day and night; counter-attack on the defensive; sparing use of ammunition; quick action against jitter parties; and flexibility off the roads. Soldiers were instructed to make the jungle their friend, travelling lightly and always staying alert.

Major-General Douglas David Gracey (1894–1964), commander of 20th Indian Division, 1942–46.

20th Indian Division’s formation badge. According to Major-General Douglas Gracey, the sword stood for ‘courage, chivalry, and vengeance.’

The division saw action in Assam and Burma, where it fought on the Imphal Plain and crosssing the Chindwin and Irrawaddy rivers. It played a key role in the attack on Mandalay. Following its recapture of Magwe and the Burma oilfields, the division pursued the Japanese down the Irrawaddy valley to Rangoon. At the end of the war it was transferred to Indo-China to disarm Japanese troops, and was disbanded in March 1946.

The division was raised at Jhansi on 1st January 1942 and was commanded by Major-General Reginald Savory. Most units joined the division at Ranchi and continued training at Lohargaga. Its main role for the next two years was patrolling on the Assam–Burma border, covering the retreat from Burma and later as a diversion for the First Chindit Operation. It was in reserve on the Imphal Plain until January 1944. By March, the division was dispersed with 1st Indian Infantry Brigade at Kuntaung, 49th Brigade at Ukrul and 37th Brigade training with 254th Tank Brigade and 50th Parachute Brigade. Both 37th and 49th then moved to the Tiddim Road to support the fighting withdrawal of 17th Indian Division. The 4/5th Maharatta Light Infantry of 49th Brigade stayed behind in the Ukrul area and fought in the very important delaying action at the Battle of Sangshak, alongside the 50th Parachute Brigade: the battalion suffered 260 killed, wounded and missing. The 23rd Division fought in the battles for Shenam. In December the division underwent training for combined operations, as it was earmarked for Operation Zipper, and landed in Malaya after the surrender. It then transferred to Java in an internal security role and was heavily involved in fierce street fighting. It returned to Malaya and was disbanded in March 1947.

Major-General Ouvry Lindfield Roberts (1898–1986), commander of the 23rd Indian Division, 1943–45, during some of the toughest fighting of the Burma campaign.

The formation badge of 23rd Indian Divison was conceived by the Divisional Commander, Major-General Reginald Savory, who later played a vital role as Director of Infantry. The red fighting cock was intended to be symbolic to both British and Indian Army troops while not alienating Hindu or Muslim troops. It was also meant to have a slightly bawdy interpretation. Savory said that frequently he had to insist that the result was ‘a fighting cock, not a bloody rooster’. It was designed by Lieutenant-Colonel L.F.A. ‘Busti’ Maddocks.

The 25th Indian Division was raised in Bangalore from August 1942. As part of Southern Army, the division’s role was to defend Southern India against a possible Japanese invasion. It then undertook jungle training at Mysore, which was completed by December 1943. The division fought in the Third Arakan campaign. It was earmarked for Operation Zipper but left Madras after the surrender of Japan and accepted the surrender of the Japanese Army in Kuala Lumpar. The division was disbanded in Malaya in February and March 1946.

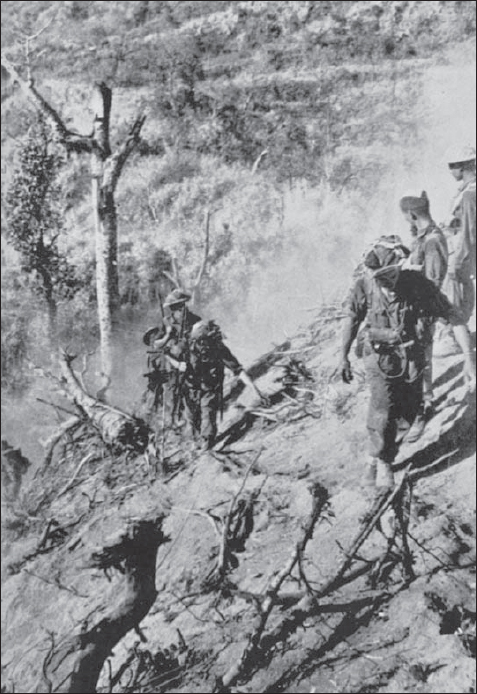

Infantry of the 25th Indian Division scramble up one of the countless steep features of the Arakan.

Major-General Henry Lowrie Davies (1898–1975), commander of 25th Indian Division from August 1942 to October 1944. He later joined the team of military historians who worked on the official history of World War II.

25th Indian Division’s formation badge, which prompted the nickname the ‘Ace of Spades Division’.

The 26th Indian Division was raised at Barrackpore from March 1942 as the Calcutta Division. It fought in the First, Second and Third Arakan campaigns and in the recapture of Rangoon. During the disastrous First Arakan campaign in April 1943, with little jungle training and no time for acclimatisation, 26th Indian Division relieved the exhausted 14th Indian Division. Major-General Cyril Lomax then took over command of both divisions from the dismissed Major-General Lloyd. The division covered the retreat after the Japanese counter-attack. It was relieved in September by 7th Indian Division. In the Second Arakan it played more of a support role. On 21 January 1945 the division was tasked with the capture of Ramree Island to provide an air supply base for the 14th Army. It was a successful combined operations attack with the town secured 19 days later. The division was next involved in the occupation of Rangoon. It returned to India in June and was to be one of the divisions involved in Operation Zipper. Its role was changed to an internal security role for Siam, but as the situation worsened in the Dutch East Indies, two brigades were sent to Medan. It was disbanded in January 1947.

26th Indian Division’s formation badge. It was called the ‘Tiger Head’ division after the Royal Bengal tiger stepping out of a triangle. The triangle represented the delta formed by the River Ganges; the division had been responsible for the defence of Calcutta in 1942.

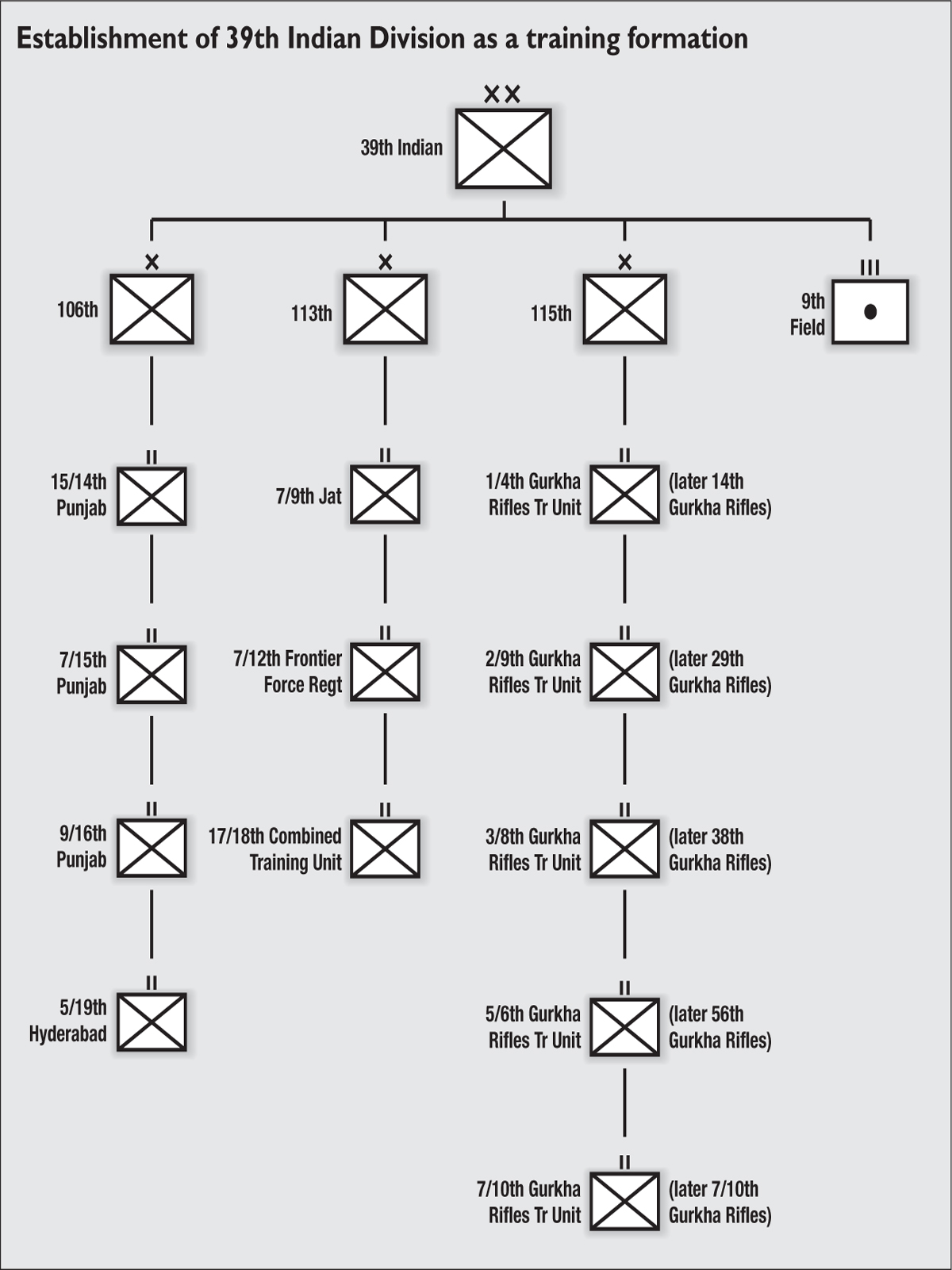

39th Indian Division was originally formed as 1st Burma Division (‘Burdiv’) in July 1941; in 1942 it was re-designated the 38th Light Indian Division. As there was a Chinese 38th Division in theatre, after just one day it became the 39th Light Indian Division. It comprised two brigades, six mule and four jeep companies. It later became a training division in August 1943 and consisted of 106th, 113th and 115th Indian Infantry brigades. The 115th Brigade comprised the amalgamated 14th, 29th, 38th and 7/10th Gurkha battalions. For instance, the 38th Gurkha Rifles were made up from the 3rd and 8th Gurkha Rifles, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel W.R.J. Spittle. Major S.C. Pickford was the training major for this new battalion, based in the Siwalik Hills. Despite having no previous experience of the jungle, a hurried attempt was made to learn before the first recruits arrived, by carrying out extensive patrols in the Siwalik Hills. Lessons learnt included the difficulty of marching to compass bearings and the importance of physical fitness. Pickford realised that once the jungle and the climate had been overcome, the Japanese would not present a problem. His training programme proved highly effective and was later adopted by the whole division.

Major-General Cyril Lomax (1893–1973), who commanded the 26th Indian Division from April 1943 to April 1945. He served with the Welch Regiment during the First World War and became Colonel of the Regiment 1949–1958.

The formation badge of 39th Indian Division.

As there was no need for an Indian Armoured Division in South-East Asia, 44th Armoured Division was disbanded in March 1944 and its HQ and divisional personnel were used to form 44th Indian Airborne Division in April. The establishment of the division was one air-landing brigade and two Indian parachute brigades each of one British, one Gurkha and one Indian battalion. A battalion group from 50th Indian Parachute Brigade dropped onto Elephant Point in the retaking of Rangoon on 1 May 1945. This was the only time Indian airborne troops fulfilled their airborne role.

The motif of Bellerophon astride a winged Pegasus on 44th Indian Airborne Division’s formation badge was suggested by the novelist, Daphne du Maurier, who was married to Major-General F.A.M. ‘Boy’ Browning – the first divisional CO of 1st British Airborne Division. The motif was worn by 1st British Airborne Division and 6th Airborne Division, and was also adopted by 44th Indian Airborne Division.

The 8th Australian Division was formed on 1 August 1940, and was the only formation of Australian Military Forces used in South-east Asia. Originally it consisted of three brigades: the 22nd, 23rd and 27th. Major-General Gordon Bennett took over its command from General Sturdee on 24 September. Bennett was a very forceful character, often at odds with his fellow Australian generals, Malaya Command and even the brigadiers under his own command. He eventually secured a definite role for the Australian forces in Malaya with the Johore area coming under his command: 8th Division now comprised 22nd Brigade commanded by Brigadier Taylor, and 27th Brigade, which arrived on the 15th August under Brigadier Maxwell. Later, 45th Indian Infantry Brigade also came under its command.

The colour patch of 8th Australian Division Headquarters.

The Australians of 8th Division also took more than a passing interest in jungle training. Brigadier H.B. Taylor of 22nd Brigade was posted ahead of his brigade to make a tour of all the British and Indian Army units in Malaya. He concluded that very few were advanced in training for jungle warfare except for the Argylls. Like most of the Indian formations, the Australian Division had trained for desert warfare. Both Taylor and Major-General Gordon Bennett, Divisional GOC, realised the importance of jungle training. Major C.G.W. Anderson, CO 2/19th Battalion, was made responsible for jungle training, since he had gained valuable experience whilst serving with the King’s African Rifles in East Africa during World War I. Their doctrine was also partly based on the Tactical Notes for Malaya, which was reprinted in Australia, and was issued on arrival in Malaya.

The Australian action at Gemas on 14 January showed the importance of jungle training. 2/30th Battalion commanded by Brigadier Galleghan laid an ambush for the advancing Japanese forces. About 300 enemy soldiers on bicycles were allowed to pass the ambushing forces on the road to Gemas and go over the bridge at Sungei Gemencheh; however, when a further 700–800 came towards the position, the ambush was set off by an explosion on the bridge. Several hundred Japanese died, in contrast to 80 Australian casualties. This was the first part of the Australian learning curve in jungle warfare, which was steepened a year later by the Australian victory at Milne Bay in New Guinea. The remainder of the Johore defensive line was made up of the retreating 9th Indian Division, the newly arrived and un-acclimatised 53rd British Brigade of 18th Division, and the ill-trained 45th Indian Infantry Brigade. However, the Japanese also had reinforcements, namely the Imperial Guards divisions, who destroyed 45th Indian Infantry Brigade at Muar and forced the withdrawal to Singapore Island where the Australians took up position on the west of the island.

The formation badge of 11th East African Division. The double-horned rhino adopted by the division was only found in East Africa and in particular in Kenya and Tanganyika. When 21 (East African) Infantry Brigade arrived in Ceylon it featured a whole rhino on its badge motif, but had to abandon it as 1st Armoured Division’s badge was very similar. Ceylon Army Command sanctioned the division’s new badge on 23 August 1943.

The 81st West African Division was formed on 1 March 1943 in Southern Nigeria. It was the first division ever to be formed from units of the West African colonies of Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. 3rd Brigade was from Nigeria, 5th Brigade from the Gold Coast, and 6th Brigade was mixed with battalions from the Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Gambia.

The importance of collective jungle training was also appreciated outside India, as some jungle training was carried out in Africa prior to the movement of 81st West African Division to India and then Burma. For example, Captain Denis Arnold of the 7th Nigeria Regiment attended the West African Training School at Enugu for jungle training in 1942, before undergoing further training with the Chindits in India.8 As Major-General Woolner commented in his divisional report, at this time there was no accepted jungle warfare doctrine or even a training pamphlet. The Royal West African Frontier Force produced its own Platoon Battle Drills and Jungle Tactics for the RWAFF in September 1943, which encompassed internal security experience, as well as that of a more conventional nature learned during World War I. However, once again there was no central coordination for jungle training.

The formation badge of 81st West African Division. The divisional commander, General Woolner, chose the black spider design, which represented Ananse, a figure in Ashanti mythology who could overcome his enemies through guile. The badge was worn head down so it would appear to be going forward when a soldier was about to fire his weapon. The spider was often mistaken for a tarantula, but these were not indigenous to West Africa.

82nd West African Division’s formation badge. It shows two spears crossed on a native carrier’s headband and symbolised ‘Through our carriers we fight’. This showed the important role the carriers played in the movement and supply of the division, even carrying 3.7in. howitzers. The yellow on black colouring was adopted to conform with that of 81st West African Division.