The disastrous Malayan campaign of 1941–42 was a shocking defeat for British arms. It was carefully analysed by British officers and it quickly became apparent that ‘milking’ was a fundamental problem affecting all British and Indian units. They were also eager to discern lessons for troops in Burma and those under training. Early lessons were incorporated into a revised edition of MTP No. 9 in January 1942. This training manual discussed the Japanese infiltration and outflanking tactics and the use of local disguise by the Japanese forces, which made it very difficult for Commonwealth troops to recognise them. The Japanese troops travelled lightly and made good use of tanks, which had previously been discounted by Malaya Command as they had been seen as unsuitable for the terrain. It remarked on the use of Japanese snipers who used chained dogs to give warning of any approaching enemy. It maintained that the main defence against these Japanese tactics and ruses in the jungle was defence in depth, more mobile and less heavily laden troops, good fire discipline, withdrawal and immediate counter-attacking.

The early lessons from Malaya were also incorporated into the Army in India Training Memorandum (AITM) series that was used in India to disseminate the latest tactical lessons and training information. AITM No. 14 published in February 1942 reiterated the general lessons from Malaya, such as keeping equipment to a minimum, a single light machine gun per platoon, the issuing of rifles or Thompson sub-machine guns to all soldiers, good fire discipline, frontal attacks only as fixing operations, and immediate counter-attacks. The example of the Argylls’ action at Grik Road was cited, where the Japanese became a ‘herd’ once they lost the initiative, showing that the Argylls’ training methods were successful. It demonstrated that static defence was inappropriate in the jungle and that defence in depth was essential to prevent any encircling movements. At Grik, for example, the Argylls operated at a depth of eight or nine miles. Accordingly, the ratio of casualties was five to one in the Argylls’ favour. The April 1942 AITM listed the three most important lessons from Malaya as being the passing on of information, patrolling, and high standards of physical fitness and discipline. Areas where specialised training were seen as lacking were road discipline, anti-aircraft small arms defence, anti-tank defence, concealment and the lack of offensive spirit. There was little mention of jungle training, but rather a general need for the toughening up of troops.

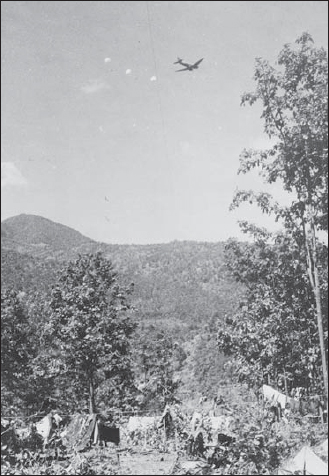

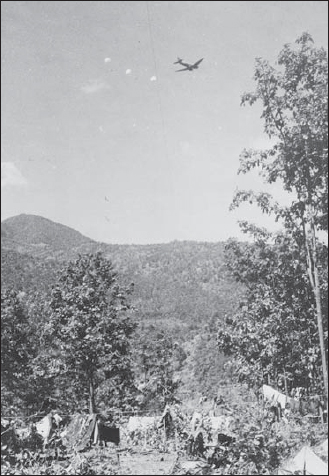

Dakotas dropping supplies to the 5th Indian Division on the Tiddim Road. Air supply was vital to the success of the campaign in Burma. One of the first successful air supply drops on the North-East Frontier was carried out to Soutcol at Kyauktaw. Previously air supply had been used on the North-West Frontier and in the First Chindit operation. (IWM IND 3966)

The British High Command made an immediate effort to learn from the debacle in Malaya, ensuring that trained and experienced officers and specialists were evacuated. Brigadier Stewart and three other Argylls – Major Angus Rose, Captain David Wilson and CSM Arthur Bing – were evacuated from Singapore to impart their knowledge to units in India. En route Stewart also passed on his knowledge to the Australians in Java and on the voyage to Ceylon. Indeed, it is generally accepted by Australian and British historians that it was Stewart’s experience, rather than Gordon Bennett, which helped to advance the learning curve in jungle warfare in the Australian Army. It was following consultation with Stewart that the Australians produced a pamphlet on Japanese tactics in Malaya, which was distributed throughout the Australian Army.

The Argylls made lecture tours of India. Stewart also made a radio broadcast about the campaign to build up morale, and prepared a report. Major Richard Storry, another evacuee from Singapore, attended a lecture by Stewart at the Intelligence School at Karachi and commented:

The lecture was a most outspoken, in parts bitter indictment of the higher planning and conduct of operations in Malaya. Mistakes of strategy and tactics were analysed, Jap methods described and Col Stewart’s own theories of counteracting them explained. It was a merciless post-mortem which impressed us all. This lecture Stewart gave, I heard, up and down India that spring 1942. Later he was one of those who directed the training of units for operations in Burma; so much, I think, is owed to him.13

Following the completion of the lecture tours in India, the evacuated Argylls made up No. 6 GHQ Training Team, which organised training exercises and lectures for 14th Indian Division and 2nd Division. Apart from Stewart the other Argylls remained in India to instruct. Rose was in the training team until 1943 and then set up the Jungle Warfare Training Centre at Raiwala, before commanding a battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers in Burma. Captain David Wilson and CSM Bing became chief instructors at 2nd Division’s Battle School at Poona. On Stewart’s return to the UK, his report on the lessons from Malaya was reprinted for use by the UK Home Forces. Stewart was back in the Far East by 1944, when he was appointed Brigadier General Staff 11th Army Group with responsibility for training.

Several other officers who had fought in the campaign also wrote detailed reports pinpointing the lessons learned. Brigadier Carpendale, CO 28th Indian Infantry Brigade, was another officer evacuated from Singapore, and his findings also noted the importance of jungle training. Some war correspondents also studied the lessons from Malaya. Ian Morrison, correspondent for The Times, was the first to publish some very clear lessons from the disaster. As early as May 1942 he noted in his Malayan Postscript that the Japanese had learnt the art of encirclement after years of fighting the Chinese who had developed these enveloping tactics against invaders. Morrison also highlighted the way they deceived defending forces by wearing Malay and Chinese costume; their survival on minimal food, mainly a diet of rice; and their use of natural resources such as rivers, aided by local guides and transport such as bicycles. He stressed their use of weapons particularly suited to the jungle, such as the 2in. mortar and hand grenades. He also stressed the importance of training for jungle warfare to counteract the efficiency of the Japanese in the jungle.

The majority of the reports on Malaya were drawn up for Major H.P. Thomas, who prepared a detailed and influential report for the C-in-C during the early summer of 1942. In this process he also interviewed over a hundred officers. The findings did state that a detailed account would never be available due the destruction of official records prior to capitulation. All the reports from Malaya hammered home the importance of appropriate minor tactics and training for jungle fighting. It was now up to the high command to put this into practice.

The lessons of the retreat from Burma were closely studied in India as soon as Burcorps had escaped, as arguably it provided far more relevant information than the events in Malaya. It was generally acknowledged that failure in Burma was due in large part to a lack of training in jungle warfare. 7th Armoured Brigade was an exception in that it had not undergone any jungle training; however, its role was mainly limited to the roads and it was only involved in the operations after the fall of Rangoon, in the open plains of Burma rather than in the earlier jungle battles. Other formations such as the 48th Indian Infantry Brigade under Brigadier Cameron performed admirably after experience in the jungle, particularly when his brigade adopted the tactic of ‘all round defence’ in the jungle. The lack of military intelligence, the low priority of the Burma front, the ‘milking’ of British, Indian and Burmese battalions, the swapping of command between Burma, the War Office, GHQ India and ABDA Command, and the decision to decline an offer of more Chinese divisions, all contributed to the defeat in Burma. The lack of jungle-trained troops, however, was the most decisive factor in the defeat in the view of many of the participants. In fact, the previous training of the Indian Army had been inadequate for the jungle conditions of Burma, because the little training that 17th Indian Division had undergone was geared towards desert warfare.

Major Wako Lisanori of 28th Army hands his sword to Lieutenant-Colonel Smyth of 1/10th Gurkha Rifles, 63rd Brigade, 17th Indian Division, at Abya in August 1945.

Tactical lessons learnt in Burma differed from those in Malaya. For instance, flanking movements were seen as difficult to support and beyond the abilities of the war-trained army whereas the importance of overwhelming firepower was realised in defeating roadblocks. In attack ‘Blitz’ tactics were successful, where light machine gunners and those with Thompson sub-machine guns led the attack with riflemen following. The importance of patrolling was acknowledged but better communications, maps and intelligence were needed to make patrols more successful in the jungle. Finally, rather than detailed orders, conferences and the issue of instructions were seen as ways to decentralise command on very mobile fronts; junior leadership was seen as the key to success against the Japanese in the jungle.

The most detailed investigation was produced soon after the arrival in the Imphal Plain; Major-General Cowan, GOC 17th Indian Division, instructed Brigadier Cameron and a committee of battalion commanders to identify new training, tactics and equipment needed to fight successfully in Burma. The committee produced the Cameron Report, which recognised that training in the jungle was vital; movement and control in the jungle became second nature, and all arms had to be trained in jungle warfare and be responsible for their own protection. All the lessons from Malaya and Burma were eventually encapsulated into the third edition of the jungle warfare training pamphlet MTP No. 9.

The First Arakan campaign was yet another dismal failure with defeat inflicted on Commonwealth troops by a numerically inferior force. However, lessons were learnt at actions such as Donbaik, and these gave troops valuable first-hand experience of jungle warfare (with its poor visibility, and patterns of quiet days with some shelling and mortaring followed by main Japanese attacks coming in at night). General Wavell and Lieutenant General Irwin attributed the failure to poor regimental command and the lack of training, which in fact reflected badly on themselves rather than on their subordinates. This situation was not helped by Wavell’s continued underestimation of the Japanese Army, a common fault prior to the Japanese invasion of South-East Asia; he could not understand why the Indian Army could not defeat it.

Administrative problems were vast considering the large distances involved. Pack transport was the main source of supplies and this depended on reasonable weather to keep the routes passable. One of the first successful air supply drops on the North-East Frontier was carried out during the First Arakan. The adoption of air supply, when sufficient transport planes became available, formed a solution to the supply difficulties. Generally supplies got through, but it was a very slow process. A number of lessons were learnt in this area, such as the importance of basic jungle-warfare training, the arming of all the administrative units, the need for a special ration to be used in emergencies for periods of up to a week, the need to encourage living off the land, and the use of air supply to counteract enveloping tactics.

The Arakan campaign had been a tactical failure. Repeated attacks on a narrow front against the bunkers had proved disastrous at an early stage, and the encircling tactics employed by the Japanese at the end of the campaign had again proved decisive. It was now realised that artillery, tank or air support was needed for attacks against these entrenched positions. Infantry weapons needed adjustment; for instance, anti-tank rifles could be kept in reserve and fewer 3in. mortars should be carried (due to the weight of the ammunition). Patrolling was seen as being of paramount importance in attack and defence, and defences had to be secure. The outstanding failure of the campaign noted by most reports was the overall low level of training and the very low standard of training of reinforcements. Large numbers were needed but were arriving from regimental depots with little basic training, let alone jungle warfare training. Generally, the First Arakan caused military and civilian morale in India to plummet. The myth of the Japanese superman in the jungle was at its peak and questions were raised as to whether the Indian Army would ever be capable of defeating the Japanese.

The Infantry Committee led the way in the development of jungle warfare doctrine and training by proposing the setting up of the training divisions and the need for a centralised doctrine for jungle warfare. These proposals were put into practice by General Auchinleck and GHQ India. All training establishments in India were now re-orientated to teach jungle warfare and produced a supply of jungle-trained instructors, cadres and complete units. This new training structure developed very quickly and by the end of 1943 India had a comprehensive structure in place. This undoubtedly played a key role in the defeat of the Japanese Army.

The fighting in the Arakan, Imphal and Kohima areas bore out the importance of jungle training as well as air superiority, organised logistics and good leadership. It showed what resolute jungle-trained troops, with confidence in themselves and their leaders, could achieve in battle. The actions at the Admin Box, Jail Hill, Nunshigum, Kohima and Imphal demonstrated the successful use of infiltration tactics and aggressive patrolling when fighting in dense jungle against the IJA. It showed the benefits of tank, artillery and air co-operation and demonstrated the resolve of support units, all of which was made possible with thorough jungle training. Even though the jungle was a difficult environment, it was no longer one that caused alarm or fear among Commonwealth soldiers. The troops of the 14th Army had grown considerably in confidence and were no longer afraid of this environment or the Japanese, and they displayed increasing battlefield effectiveness with aggressive tactics in both defence and attack.

The 14th Army was by no means perfect by the summer of 1944, but now had the upper hand over the Japanese. The divisions were prepared for the next phase of the fighting and absorbed the lessons of the recent operations. They were not only trained for jungle warfare but also for air-mobile and amphibious operations, and for the open warfare on the central plains of Burma.

Training and doctrine were not the only factors in the re-conquest of Burma and inflicting the biggest land defeat on the Japanese Army. Equipment was no longer in short supply in SEAC by the summer of 1944, in contrast to the previous low priority accorded to this theatre. The troops had managed on the little they received, and adapted its use to the jungle environment, such as dyeing equipment and uniforms jungle green. Also, as Louis Allen has pointed out, the battles in Burma were not won solely in the jungle; the later victories were fought in the open. Other factors that were crucial in the defeat of the Japanese included improved logistics and air supply, medical advances and health discipline, artillery, tank and air support, high morale and good leadership.

The recognition of the need for training in jungle fighting, a jungle-warfare doctrine and extensive jungle experience in World War II aided the British Army in later campaigns in the Far East. During the Malayan Emergency 1948–60, Ferret Force, a scratch unit of British, Gurkha and Malay troops who had fought in the jungle during World War II, discovered 12 Communist guerrilla camps in 1948. It was also reflected in the careers of General Sir Walter Walker and Colonel John Cross. Walker was an operational director in the Malayan campaign and the director of operations during the Borneo Confrontation 1962–66. He set up the Jungle Warfare School in Johore, which was run by Cross for a long period, both having served their jungle apprenticeships in Burma.

13 Major G.R. Storry, Service with the Intelligence Corps in India and Burma March 1942–May 1943 (Unpublished Memoir, 1946–1947), Storry Mss., IWM 01/34/2, 6/10.