FROM MODEST BEGINNINGS

For years, even before starting to research Mannock’s life in detail, we were always aware that his birth place and date, appeared to be uncertain. In various publications one can read that he was born in Brighton, Canterbury, Aldershot, India, and Cork. The reason for this was due to his father being in the army and having been stationed in various places during the late 1880s.

Ira Jones wrote his biography of Mannock in 1934, stating 24 May 1887, in the Preston Army Barracks, Brighton. In 1963, in their book Ace with One Eye, Frederick Oughton and Vernon Smyth quoted the same place and date. (Apparently this book was written by Oughton from information supplied mainly by Smyth.) However, Oughton, in his book covering the entries in Mannock’s diary, in 1966, appears to have either made a typing error, or disagreed with Smyth’s date, and recorded 1889 as the year of birth.

In a Canterbury newspaper in 1978, the date 21 May 1887 is recorded, and again Brighton, but the writer quotes the Ministry of Defence as showing 1888, and that they believed he was born in Aldershot. James M Dudgeon in his book Mick, in 1981, records 24 May 1887, with Cork as the birth place. Chaz Bowyer, in his book on Air VCs in 1992 says Brighton on 24 May 1887, while in 2001, Adrian Smith in his book Mick Mannock Fighter Pilot, shows 21 May 1888, Brighton.

A search at Somerset House has thus far not revealed a birth date or place. Children born to fathers in the army were often recorded separately, but there is no record of his birth there either. Perhaps Cork is the correct location, where a mention in UK records would not be made. Mannock himself confused the issue by recording both Brighton and Cork on documents.

Mannock’s father, Corporal Edward Mannock, had joined the 2nd Dragoons – Royal Scot Greys – under his own mother’s maiden name of Corringhame, for reasons best known to himself, and is described as being a soldier of fine physique. In 1881, the 2nd Dragoons had been stationed on the outskirts of Cork, in southern Ireland, where he had met and courted Julia O’Sullivan, then married her in 1882. Julia had lived in a suburb of Cork, the village of Ballincollig.

The couple moved with the regiment to Edinburgh, and soon afterwards Corporal Corringhame was sent to Egypt, Julia returning to Cork while he was overseas. While away fighting with the Heavy Camel Corps, a daughter Jessie (Jess) was born and upon her father’s return the family moved into the West Cavalry Barracks in Aldershot, Hampshire in 1886. That same year a son Patrick J was born and in early 1887 another move came, this time to the Preston Cavalry Barracks, Brighton. This is how Mannock’s birth place is deduced, but it may be that Julia again returned to Cork (her husband possibly on manoeuvres in Ireland), and it was here that a second son, Edward, came into the world, on 24 May 1887.

The young Edward Mannock does not help settle the matter of his birth, although he undoubtedly had reasons for leaving red-herrings around for future historians. When he joined the Territorials in 1915, he actually wrote on his entry form that his date of birth was 24 May 1888! In early 1914 on the occasion that Mannock applied for a passport to travel to Turkey, he again wrote in his own hand that he was 24 years of age, whereas he was actually 26. Confusion over his birth place is again due to Mannock. On the occasion he received his Royal Aero Club flying licence, it records his place of birth as Cork. One might have thought that to enter an incorrect age on a passport document, then to show Cork as his birth place on his flying licence if incorrect would have been rather a stupid thing to do so perhaps Cork at least is correct. Certainly when he joined the Royal Flying Corps, they noted his birth date as 24 May 1887. According to James Dudgeon, he was told by family members that Cork was correct.

The Mannock family c1900. Seated, Mrs Julia Mannock, with (left to right) Edward, Jess, Patrick and Nora.

Army life for Edward senior continued, with postings to Louth, Ireland, Newbridge, near Belfast, and from the latter the corporal ended his period of army service. For a while the family lived in various places around London, but the soldier’s heart was still with the military, and during a visit to Liverpool, he suddenly re-joined the army, even giving his proper name of Mannock as he did so. He became a trooper with the 5th Dragoon Guards, then stationed in India, and six months later, Julia Mannock and her three children arrived in India to join her husband, and were to remain there for almost six years.

The young Mannock appeared quiet and reserved by nature and was rarely seen charging about with other children, and was more often than not found reading or deep in thought. It was in India that he first became aware of a slight defect in his right eye. For a while he seemed totally blind in that eye, but the condition gradually returned to almost normal within a few months. He liked football and cricket, and while he enjoyed target practise with an air-rifle or even a bow and arrow, never tested his skills against living targets such as birds and animals.

His father had regained his old rank of corporal by the time the regiment went to active duty during the South African war where he saw a good deal of action, although his family naturally remained in India. By now a further daughter had arrived, Nora.

At the culmination of that war, Corporal Mannock’s second period of service was again nearing the end. Returning to England he went first to Shorncliffe, then to the cavalry depot at Canterbury where his wife and children joined him. Within a few months he left the army and the family took up residence in Military Road, Canterbury. Then, quite out of the blue, Edward Mannock senior left, completely abandoning wife and family. He never saw them again, nor supported them in any way at all from that day on. [1]

Young Edward – he was often referred to as Paddy, or Eddie – was 12 years old at the time his father left. Despite this desperate turn of events, Julia dug in her heels and stoically went on undeterred, helped in part by small incomes from Jess and Patrick. The family had never been well-off, and now they existed on the bare minimum, but exist they did, and she kept them all together, long enough to have them eventually fend for themselves.

In September 1905 his sister Jess married. The Mannocks were now residing in St Peter’s Street, Canterbury and the wedding took place at St Thomas’s catholic church in the town. Jess’s husband Edward Ainge (Ted) was in the army, his address given as Canterbury Barracks.

Another pilot who flew with Mick in 40 Squadron during 1917, was C O Rusden. He later recorded in a 1957 letter to one of Mannock’s biographers (Vernon Smyth):

‘He was very conscious of his social background and never sought the limelight for that reason more than any other.’

Meantime, Edward was making friends in Canterbury. He was a member of the St Gregory’s cricket team, and with an interest in religion had joined the Church Lads Brigade, even though he was a catholic. They had a band, and Edward did good work with the kettle-drum. Someone who recalled Mannock at this time for Vernon Smyth in 1957, was S J Powell, then living in Whitstable, Kent.

Powell had related that he had known Mick when he was living in King’s Street, Canterbury, when Mick was working for the National Telephone Company, and remembered him as being ‘… in poor circumstances.’ Powell often took Mick home for evening meals and sometimes his mother would give him a parcel of underclothes.

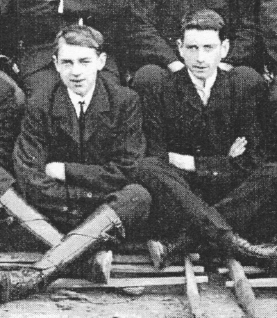

Patrick and Edward at a telephone company outing to Deal in July 1904.

Powell also related how Mick later had helped form the local Territorial Army unit and played a bugle in the band, and that while others might read the occasional book, Mick always seemed to be reading and studying a dictionary! He remembers him as tall, reticent, serious-minded, and modest. Mannock would often suddenly burst out excitedly for a few seconds over something, and then quite unexpectedly revert to his normal quiet manner. So, whether kettle-drum or bugle, Mannock had some musical talent at least, and was improving himself by reading.

Edward was going to St Thomas’s School, but he needed to earn money at the earliest opportunity. Brother Patrick had got himself employment as a clerk with the National Telephone Company in the town, and he contemplated joining his brother with this firm. However, Edward did not fancy being a clerk, preferring outside work, so he become a messenger boy to a local greengrocer but after a few months moved to become a barber’s assistant. This did not suit him either, so he managed to join Patrick as a clerk, but although better paid and with shorter hours, the job was not to his liking. Still longing for outside work he succeeded in getting himself accepted to fill a vacancy as a linesman, assisting the engineers. Scrambling up telephone poles had some appeal apparently. The downside to this was that the vacancy was in Wellingborough, so he had to leave the family home and Canterbury, and find himself digs in the Northamptonshire town.

Luck was with him and he fell firmly on his feet. He found lodgings with Mr and Mrs A E Eyles, 64 Melton Road, Wellingborough. (They later resided in Mill Road.) Their meeting was quite by chance, for Edward had started to play for the local Wesleyan cricket team, and Jim Eyles was also a member. Obviously living accommodation came up in conversation and Jim suggested he come and live with them, which he did. Jim Eyles and his wife ‘May’ (they had married in September 1908) became a second father and mother to him and remained so for the rest of his life. Eyles was the manager of the Highfield Foundry and Engineering Company in Wellingborough, and he liked Edward a lot, and took him under his wing. They too knew him as Paddy.

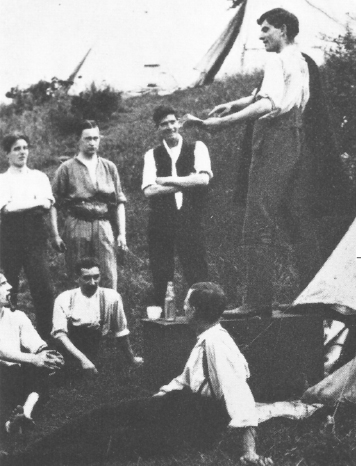

Edward expounding on his political theories to a group of YMCA friends in 1911.

Later Jim Eyles was to record that Paddy was a keen cricketer and in the Wesleyan club played as wicket-keeper: ‘… a position needing a keen eye.’ (So much for a serious eye problem!) He recalled too, Edward joining the local parliamentary debating society as well as becoming the secretary of the local branch of the labour party. He remembered also his infectious laughter, and the fact that he taught himself to play the violin.

All in all he is described as quiet and reserved, in many ways self-educated and a profound reader. He was also fond of music. One thing he abhorred was snobbery and sham. Mick also decided to join the Home Counties (Territorial) RAMC – Royal Army Medical Corps – so that despite moving up north, he would be certain to meet up with his old TA mates each year at summer camp. He achieved the rank of sergeant shortly before 1914.

With a few shillings in his pocket he opened a bank account. This was in 1912 but he quickly fell foul of the bank manager. A letter survives written by Mannock to the manager.

64 Melton Road,

Wellingborough.

15 April 1912

Dear Mr Cook,

I enclose herewith postal order value 10/-which please credit to my account. This will leave a debt still outstanding amounting to 9/-which I will send you later.

I rather regret that you should adopt such a tone in your letters regarding this matter, more so in view of the fact that the account itself has only been contracted since September last, and you may have known that money was safe.

Yours faithfully,

Edward Mannock

One has to smile on reading this, for it seems that the young Edward Mannock thought he must be doing the bank a service by having an account with them.

Life might have easily jogged along had it not been for Mannock’s desire for some form of promotion. The job of assistant to an outside telephone engineer did not excite him especially with no immediate prospect of advancement. With so many young men of the age heading for varied foreign climes – Canada, South America, South Africa to name a few – Mannock suddenly decided that telephone engineers might be eagerly sought after in some developing countries. Why exactly he chose Turkey is unclear, but shortly after Christmas 1913, he informed Mr and Mrs Eyles that he planned to head away from England. At that stage he was happy to contemplate not only an extension of the job he knew, but again, like so many others, had tea planting or cattle ranching in his mind.

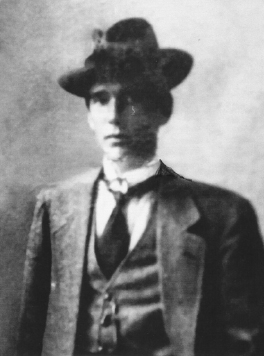

He applied for a passport, and this document survives to this day in the RAF Museum, Hendon. Unlike the passport documents we know now, this is a large 11” x 8” (29cm x 20cm) sheet of white paper, that feels like those old £5 notes that went out in the 1950s, folding to make four sides. A small snap-shot of the holder was glued to the front page, and on the back of the last page are the stamp impressions of the various countries he travelled through. This passport paper is dated 10 January 1914 and Mannock describes himself as a telephone and telegraph mechanic.

Borrowing money from Jim Eyles and brother Patrick, Mannock boarded a tramp steamer in February 1914 and worked his passage to Constantinople. After his arrival, he sought an interview with the manager of the English Telephone Company, and got a job as an outside engineer. He worked for this company during the spring and summer of that fateful year even rising to the position of district inspector, but when war was declared in August, and Turkey looked as though it would come down on the side of Germany, Mannock, along with other foreign workers, became aware of anti-European feelings, especially against the British. Work consequently dried up, as did wages and access to food that could be afforded. By October some work had started again but the following month, with sides finally taken, Mannock became interned, as a prisoner of war.

Edward Mannock’s passport photograph in 1914.

Silence followed, no letters being received from him, and finally Jim Eyles contacted the American embassy in Turkey for news. They managed to discover that Mannock was well and still in Constantinople, but the telephone company had been taken over by the Turks. Apparently he had tried several times to escape so had been put into a prison camp. He remained a constant irritation to his captors and in so doing became something of a hero to his fellow detainees. When guards told him England was finished, his invariable reply included thumbing his nose at them.

Finally, through diplomatic reasoning, the detainees were gradually selected for exchange, and it is believed that Mannock had begun conveying to his captors that he was virtually blind in one eye, and that this, together with his vast age – he was now approaching 28 – convinced them that he would be of little value as a soldier. This, and the fact that he was such a nuisance, made it easier to release him than keep him, so at the beginning of April 1915 he regained his freedom and returned to England.

In some cuttings that Mannock’s first biographer Ira Jones stuck into a large RAF book, there is a loose one referring to the occasion Mannock was a best man at a chum’s wedding. He signed himself A Wyler (although in correspondence to Vernon Smyth, his name appears as R Wyles), who after the war was living in Penshurst, Kent. He wrote that he had known Mannock in the Territorials pre-war and that when the war came along he had gone into the infantry while Edward went into the Royal Engineers. ‘He was my “best man” and the last souvenir he gave to my wife and me was a photograph – duly signed – and bearing these words. “The path of glory leads ….”’

Mannock in Turkey, complete with fez, 1914.

When writing to Smyth in the 1950s, Wyles recalled Mannock returning from Turkey and meeting him again when Mannock decided to rejoin the RAMC. Mannock had entered the orderly room to find his former friend sitting behind a desk as the OR sergeant. No sooner had the two friends got over their reunion, than Wyles got Mannock a job as transport sergeant. He also recalled that while they were at Halton camp, Tring, in Hertfordshire, Mick was the life and soul of the evening debates. Wyles was later commissioned into the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.

Edward in his RAMC uniform in 1915.

Mannock had joined the transport section of the 3/2nd Home Counties Field Ambulance Company. Enlisted here on 25 May 1915, on the form he had to fill-in he noted his year of birth as 1888, and in answer to the question of where he would like to go, requested either the Royal Engineers, Signal Section, or the Army Service Corps, or the infantry, but mainly desired the 101st Field Company of the REs. The army was always interested in a man’s ability to ride a horse at this time, and in answer to this question, Mannock confirmed: ‘Yes, well.’

The problem he now faced was that in the RAMC he would be expected to attend to German wounded, not just British or French. This did not sit well with him at all, so he decided to move to a more combatant role, hence his desire for the REs. One job he thought would be good was as a tunnelling officer, so that he could ‘… blow the bastards up! The higher they go and the more pieces that come down, the happier I shall be.’ Thus the mild-mannered telephone mechanic, soured by his time as a prisoner of the Turks, had become, if not a Hun-hater, certainly a Hun-disliker.

Mannock got his wish and turned up at the RE depot at Fenny Stratford, just outside Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, as a cadet. He was a good deal older than most of the other cadets and seemed rather insular. He was ill at ease with the training, but eager to get into the fighting. Like so many other soldiers feeling kept from the war, he moved to try and expedite matters, but it was quite a sudden change of direction – at least his CO thought so – to have him request a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps. Anyway, he had now received a commission, and his CO, despite thinking the move a foolish one, did not block his request. Suddenly Edward Mannock was about to start flying training.

It was now the summer of 1916 and there is little doubt that Mannock, like others, had been hearing and reading about the exploits of the airmen on the Western Front, and especially of Albert Ball, who was regularly jousting with German pilots and shooting them down. He understood too, that any eagerness to get to France would end up in the dreary and dangerous work in the trenches. Long gone were the battles in open fields and sweeping plains. Engineers and signals people would also be exposed more than most to hostile fire, when having to deal with cut telephone wires and ensuring communications between front line units and headquarters.

One obvious first hurdle would be the medical, and more especially his eyesight. Even today there are two schools of thought about his defective eye. Was it a problem or was it something that hero-worshippers could refer to, to indicate that he was a wonderful pilot and shot despite one eye. Obviously there was something amiss, but one can imagine that it was not perhaps that serious. Some of his flying chums, when asked about it, were surprised there was a problem. It might be said that some medicals in WW1 were not as thorough as later, and Ira Jones seems to suggest that the doctor merely asked Mannock if his eyesight was all right, and he had confirmed that it was, so that was that. Depth perception was really a must for pilots in order to judge distances and heights, especially when landing. Shooting might be done with one eye closed, and in any event, the fighting pilots who were to fly Nieuport Scouts and later the SE5s, generally screwed one eye to an Aldis telescopic gun-sight anyway. J W Shaw who flew with Mannock in 40 Squadron told me (Norman Franks) once that if there was any problem it must have been very intermittent. Shaw knew he had a ‘cast’ in the left eye but that he could see with it perfectly well. Overall, it can be said that the problem was not too great a one, and obviously did not affect his ability in the air in any way.

Mannock’s transfer to the RFC came in August 1916 when he was in Bedford and, as he confided to his diary, when the depot adjutant called him in to tell him, he could have kissed the man. He had his sights firmly set on becoming a fighter pilot like Ball, and as we know he achieved his aim. What might have happened had he had been selected to be a bomber pilot, or a reconnaissance pilot can only be guessed at. Mannock might have been in Bedford at this moment, but his address he gave upon joining the RFC was: Rolvenden Layne, Rolvenden, Nr. Cranbrook, Kent. His next of kin he gave as his mother Julia, 96 Ettington Road, Aston, Birmingham.

Would-be pilots often began their association with flying by a posting to No.1 School of Military Aeronautics, at Reading, Berkshire, and so it was with Edward Mannock. Yet there were no aeroplanes, just classrooms, where the new boy would be taught the theory of flight, and gain knowledge of how aero-engines work, how to rig an aeroplane, how to read a map from the air, discover the secrets of the main machine guns of the day – the Lewis, drum-fed gun, and the belt-fed Vickers – and a myriad of other subjects he would come across, not least some rudimentary history of the RFC, despite only being four years old. All military units have their traditions, and the RFC were fast establishing theirs.

Mannock was then sent for his ab initio training. However, he did not impress as a natural pilot. Training at Hendon with 9 Reserve Squadron, was far from smooth, and indeed, at one stage it was thought he might well be returned to the REs. Arthur Glendower Graves, who had been a second lieutenant in the 9th Somerset Light Infantry, passed his flying test in November 1916. He had met Mannock there, and when Vernon Smyth was researching for his book The Ace with one Eye in the late 1950s, Arthur Graves, who for some years had been the Clerk of the Peace for the County of Middlesex, wrote the following account of his recollections of Mannock at Hendon, and later at Joyce Green. Smyth was the researcher and Frederick Oughton, his co-author, did the writing, but they did not include all that Graves recalled of his time with Mannock:

‘I knew Mannock extremely well and indeed learned to fly with him at Hendon early on in the First War.

‘He was then a young man of twenty or so [actually nearing thirty] and was of a most tempestuous nature; even then nothing daunted him, and indeed, he had been at Hendon only a very short time, some two weeks or so, when becoming restless with the “eternal situation” as he called it (we had no dual control in those days) and being impatient and wanting to fly solo on his own, he went onto the tarmac early one morning (there was no-one about, just two mechanics) jumped into a Caudron and flew around the aerodrome for ten minutes or so; on landing he was severely reprimanded by the C.O., who ordered him to remain grounded until further orders.

‘In those far off days, the Royal Flying Corps having taken over Hendon, which was of course a civil aerodrome, the officer pupils and staff were billeted in the neighbourhood, mostly in Colindale Avenue, and had their meals in the then civilian restaurant on the aerodrome, which was staffed by waitresses; it did not take Mannock long to pick out the most seemly and make an appointment to take her out for a walk one evening. Unfortunately for him, however, the C.O. saw them on their return, walking down Colindale Avenue.

‘In the morning he was ordered to appear in the orderly room and the C.O. gave him a proper talking to, referring to his being an officer and a gentleman and expected to behave as such, to which Mick replied with just a little politeness: “Neither you nor anyone in the British Army will prevent me from going out with the girl I love.” To which the C.O. was unable to reply, or in any event he did not do so.

‘Mannock, restless as ever, wanted to get to France as soon as possible, and was therefore posted to his finishing squadron in England, for further experience on the War Scout machines of those days. He was soon away in France where as we all know, he covered himself with such glory.

‘He was a great humourist and was most excellent company. I did not see him again for he was soon to die doing his duty – a brave man.’

Moving on he was posted to No.10 Training Squadron at Joyce Green, near Dartford Creek, commanded by a South African, Major J G Swart MC. One of his instructors was none-other than James McCudden, as yet not famous but already a successful fighter pilot, with a Military Medal and a French Croix de Guerre. Under his tutelage he did well but he did have at least one brush with the ‘grim-reaper’.

Arthur Graves had moved to Joyce Green too, and recounted this story. The pupils were out on the airfield and had watched McCudden spin a DH2 from around 3,000 feet over the aerodrome and finally pull out very low down. Mannock, according to Graves, thought it a good show, and obviously impressed by it, sought out McCudden that evening and had a long chat with him. Next morning, there was a low cloud base but a few machines were up. Suddenly those still on the ground heard the whine of wires, and looking up saw a DH2 spinning down from about 1,000 feet.

At little more than 200 feet above the ground the DH2 came out of the spin, but pointing not towards the aerodrome but at the Vickers TNT works on the other side of Dartford Creek. It disappeared from view below the dyke and everyone watching expected the noise of a crash, or even an explosion, but there was neither. Of course, it was Mannock. He had actually managed to pull up about ten feet from one of the huts where explosives were made. He returned some time later and had his leg pulled pretty badly.

He had misjudged his height but it was typical of the man, reported Graves, that he intended to succeed at something that was considered fairly difficult. As one might expect, McCudden had more than a few words to say.

The chief flying instructor at Joyce Green was Lieutenant Edward Alexander Packe, formally with the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry. He had been injured in France and in 1916 became an instructor, firstly with 46 TS, then with 31 RS before moving to 10 RS in November 1916. He would later go back to France with 32 Squadron before returning to instructing in 1918. He ended the war with the DFC and a Mention in Despatches. At Joyce Green, Packe made most of his students very nervous by his manner, including Mick Mannock.

Mannock was sharing a room with Meredith Thomas, another trainee pilot. Thomas would become an ace with 41 Squadron in late 1917 and would rise to the rank of air vice-marshal in the RAF. In recalling Mannock he recorded:

Captain James McCudden VC DSO MC MM CdG. He was one of Mannock’s instructors in England prior to being posted to his first operational squadron.

‘We shared a room and he told me many interesting stories of his pre-war life; it appeared to have been a hard one. At this time he was a staunch teetotaller and a fairly regular churchgoer, although during chats with him he professed to have no particular religion. We were great friends at Joyce Green and had many serious and amusing talks when waiting in the cold [sitting] on a petrol bin for a flight, but I cannot recall anything definite beyond our mutual disgust because of the manner in which the staff threatened the pupils, many of whom had seen pretty severe war service before transferring or being seconded to the RFC, whilst the staff had seen very, very little, and in some cases none.

‘My first impression of Micky was that he was very reserved, inclined to strong temper, but very patient and somewhat difficult to arouse. On short acquaintance he became a very good conversationalist and was fond of discussions or arguments. He was prepared to be generous to everyone in thought and deed, but he had strong likes and dislikes. He was inclined to be almost too serious-minded.’

It would be of interest if any of his contemporaries had mentioned if he had any Irish accent. Considering his upbringing and the places and people he frequented during his first quarter century, it seems very unlikely he had anything resembling an Irish brogue. Yet he is often referred to as an Irishman, due simply to his birth-place being recorded as Cork. As his father was English, and Mick spent most of his early life among Englishmen, especially soldiers and their families in India, it would be difficult to have any chance of picking up an accent.

Once his training was complete, he received his Royal Aero Club certificate, No.3895 dated 28 November 1916, and the coveted RFC wings presented and sewn on his uniform, he awaited his first posting to a squadron. He was assessed a proficient pilot in March 1917 and posted to France, to Clairmarais near St Omer, the home of No. 1 Aircraft Depot. He began a diary now, the first entry being what would be an auspicious date in 1918, 1 April 1917, noting:

Mannock’s RAeC certificate. Note he gives his place of birth as Cork.

‘Just a year ago since I received my commission, and a year to the day earlier I was released from a Turkish prison. Strange how this date recurs. Let’s hope that a year hence the war finishes and I return for a spell to Merrie England.

‘Well. Landed at Boulogne. Saw the MLO and discovered I was to be away to St Omer the following day at 3.45 pip emme [pm]. Rested and fed at the Hotel Maurice. Quite a nice place as continental hotels go. Wisher, Tyler [1] and two more strangers (RFC) kept us company. Rotten weather. Rain. I’m not prepossessed with the charm of La Belle France yet.’

Mannock arrived at St Omer on the 2nd. Once the war had settled down after the initial rush to France in the early weeks of WW1, St Omer became the major staging post for the RFC, where aircraft and airmen came prior to posting to operational units. By the end of the war it was a vast military flying base. On the 3rd he noted he met other new RFC types, Lemon, Dunlop and Kimbell. Second Lieutenant Richard Evison Kimbell, aged 19, would be sent to 60 Squadron and be killed in action in less than two weeks (16 April). Dunlop would be posted to 40 Squadron along with Mannock, but he was seriously injured in a crash on 9 April. Brian Bertie Lemon had passed his flying tests to receive his licence on 21 November, No.3849 – a week before Mannock. Andrew Crawford Dunlop, a Royal Engineers second-lieutenant had joined the RFC in October 1916.

On 6 April Mannock received orders to report to No.40 Squadron. Mannock noted it was at Aire/Lens, although actually 40’s base was known as Aire/Treizennes. This airfield was south-east of St Omer, half way between there and Béthune. He and his meagre possessions were put aboard a Crossley tender for the one and a half hour drive to the airfield. He was met by Captain McKechnie and Dunlop, the latter having preceded him a day earlier. In due course he was introduced to the squadron commander, Major L A Tilney, who told him he would be flying with C Flight, led by Lieutenant H C Todd. Pilots awaiting postings at St Omer were generally in the queue to replace dead or wounded pilots. 40 Squadron had lost a pilot on the morning of the 6th, another had been reported missing on the 3rd (prisoner of war) and they had also lost one on 30 March. Disaster had already occurred a month earlier, on 9 March. A patrol had been caught by Baron Manfred von Richthofen’s Jasta 11, and had lost four pilots and had had two other FEs badly shot-up.

It is understood that Mannock actually replaced the missing lad who had been shot down on the 6th, Second Lieutenant H S Pell. Todd had led a special mission, an attack on the German balloon lines, a highly dangerous operation, for which 40 Squadron would become famous. Todd himself had been lucky to get back, the anti-aircraft fire being intense, as well as rifle fire from troops on the ground. Harry Pell had not been so lucky and his Nieuport 17 had been hit by MFlak 60 battery. The young Canadian from Toronto did not survive the crash inside the German lines.

Major Tilney was 22 years old, therefore, seven years younger than Mannock. A former officer with the Duke of Lancashire’s Own Yeomanry (TF), he had become a pilot in 1915 and served in France with 11 Squadron the following year. Towards the end of 1917 he received the Military Cross for his leadership of 40 Squadron, while the Belgians awarded him their Croix de Guerre, then made him an Officier de l’Ordre de la Couronne.

The Squadron was in a high state of activity when Mannock arrived, having been on the aforementioned balloon strafe that morning. Henry Todd had flamed one gasbag and had been lucky to return home. In the Mess later that day, Mannock inadvertently sat in the chair that Pell had usually sat in and there was an awkward silence – but it passed. The next day the Squadron went on another balloon raid and Todd had again been subjected to much ground fire. These had been the unit’s first operations with their new aeroplanes, French Nieuport XVII Scouts (more usually referred to in the RFC as 17s) having replaced the antiquated FE8 ‘pusher’ type scouts at the end of March.

Mannock made no reference to these events in his diary, his first few days being totally occupied getting used to the Nieuport 17 that he would shortly be flying against the enemy. He made his first ‘solo’ flight in a Nieuport on the 7th – serial number A6733 – between 0950 and 1015 am. He described it as a ‘Lovely ‘bus’, in which he ‘tootled around and went as far as the lines via Béthune.’ For the first time he saw the flashes of the big artillery guns, the trenches and the smoke of war.

That same afternoon he made two more practice flights, again in A6733 between 1415 and 1500, then in B1502, a short hop between 1835 and 1850 pm. The next morning he was taken on his first line patrol (LP) in B1502 (0750-0815) with Todd leading. This would not turn into a fighting sortie unless Todd spotted German machines over the front worrying the two-seater corps aircraft, which if it did occur, Mannock would have had orders to break away and fly home. No, this was just another practise flight, getting the new boy used to flying with other aircraft and adding to his knowledge of the area over which 40 Squadron operated. New pilots needed to become familiar with the locality in quick time as it was too easy to become lost, and a lost pilot was vulnerable.

The Squadron had been in France since August 1916 with their FE8s, and had moved to Treizennes that same month after a stop at St Omer. Their new aeroplanes had been well received by the Royal Flying Corps. They had been used by the French – in its earlier variants – for some time, and the type 16 (XVI) had been in service with the British for over a year, although in the early days employed just in small numbers with two-seater squadrons. By mid-1916 there were enough machines to equip whole units, and No.60 was among the first. The Nieuport type 17 (XVII) started to arrive on British squadrons in mid-July 1916, and by the time 40 Squadron began to receive them, at least three other RFC squadrons were equipped with the type; 1, 29 and 60.

The type XVII had a 110 hp Le Rhône engine and it was easily identified in the air because of its sesquiplane wing design – the lower wing being much narrower than the top wing. (In fact this was copied by the German Albatros Company later, which it used with their Albatros DIII and DV models.) Armament for the Nieuport in British service was a single drum-fed Lewis gun situated on the top wing centre section, fitted so that the bullets would pass harmlessly over the spinning propeller, to a point some way ahead of the aeroplane’s line of flight. A successful interrupter gear was only just being made available but the RFC – and RNAS – used only the top wing gun with their Nieuport Scouts. Much earlier aeroplanes, such as 40’s old FE8s, the other ‘pusher’ type scout, the DH2, and the earlier Vickers FB5 two-seater, plus the FE2b/d types, cleared their frontal field of fire by having the propeller at the rear.

The wing-mounted Lewis gun assembly had been the invention of a Sergeant R G Foster of the RFC, while with 11 Squadron. This ingenious mounting embodied a quadrantal slide which permitted the gun to be slid down rearwards so that the pilot could replace the empty drum with a full one. Naturally it did not take RFC pilots long to see that the gun, pulled down, could easily be used to fire upwards into the under-belly of an enemy aircraft. In this way, the first intimation of danger by the German pilot, was as bullets began slashing through the bottom of his machine. Each drum held 47 rounds of ammunition.

Later, once an interrupter gear became available, the French in particular began using a belt-fed Vickers gun mounted on the fuselage immediately ahead of the cockpit, so that the pilot could aim and fire directly at an opponent, and although the RFC used this Alkan mounting too, it really came at a time when the Nieuport Scout was being phased out.

[1] Mannock would have been only too aware of his and his family’s status in life. In 1917, in France, he confided to a fellow pilot, C W Usher about his humble origin. Usher later wrote: ‘After a discussion in the Mess one evening, during which he [Mannock] expressed himself freely on the social order, he concluded by saying, “You fellers were born with silver spoons in your mouths. I had an iron shovel.”’

[1] 2/Lt J V Wischer RGA. RAC Cert No.3792, 10 November 1916. R C Tyler, RAC Cert No.4059, 19 December 1916. Wischer (an Australian) went to 16 Squadron (BE2s) and with his observer was shot down and taken prisoner on 28 April 1917, by the German ace Kurt Wolff.