COMMANDING 85 SQUADRON

Following his visit to 74 Squadron, Major Mick Mannock drove from Clairmarais to St Omer on 5 July. Meeting his new command it seemed obvious to him that the pilots did not have the same level of morale as 74. Bishop had certainly been a figure-head but he had not developed into a patrol leader, nor had he encouraged a method of leadership that was now de rigeur in France. However, it has to be said that not everyone had doubts about Bishop. Lieutenant Elliott White Springs, one of his pilots, had recorded on his departure: ‘So our Major has gone, but if ever a CO had the respect, admiration and love of his unit, ‘twas him. The mechanics even are disconsolate.’

Springs was not to see the arrival of the new commanding officer, for he was brought down on 27 June and it was while he was in hospital that he was told he was being posted to the 148th Aero Squadron as a flight commander.

Since their arrival in France in May, 85 Squadron had claimed nearly 50 victories, half of which had been ‘scored’ by Bishop. The last ones had been claimed by Lieutenant A Cunningham-Reid, who had shot down a red and black Pfalz in flames between Bruges and Thielt, on 3 July, then drove down another out of control.

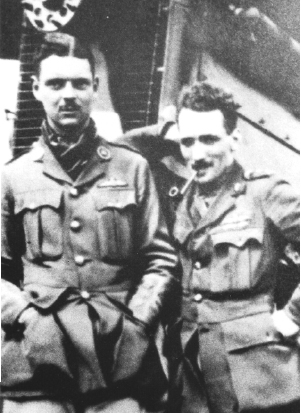

Captain G B A Baker MC, 85 Squadron flight commander. On the left is W H Longton, one of the few pilots in WW1 to win three DFCs.

Mannock’s flight commanders were experienced men. Captain G B A Baker MC, had, like Young and Cairnes in 74, cut his teeth with 19 Squadron in 1916-17, flying BE12s, a fighter version of the BE2. His MC was awarded for leadership and for flying bombing raids. By the summer of 1917 he had been promoted to captain and sent to 23 Squadron, which flew French Spads. During his period with 23, he had scored a handful of victories, then been rested. In early 1918 he moved to 85 Squadron while they were still being ‘worked up’ as a Sopwith Dolphin squadron, then helped convert the pilots onto the SE5. He was Bishop’s second in command and was just a couple of weeks away from his 24th birthday. He would become an air-vice marshal in WW2. In correspondence in 1967, George Baker said to me [NF] that as far as he was concerned: ‘The outstanding fighter pilot of the 1918 period was, without any questions, Mannock.’

Mannock’s senior flight commander in 85 Squadron was Captain S B Horn MC (left), seen here with Lieutenant J Dymond (centre) and W H ‘Scruffy’ Longton DFC.

Captain Arthur Clunie Randall commanded B Flight, and was a Scot from Lanarkshire, aged 23. He had been with the Border Regiment before joining the RFC and his first combat tour had been as a DH2 pilot with 32 Squadron in late 1916, early 1917. He would gain another nine victories with 85 and win the DFC.

C Flight was led by Captain Spencer Bertram ‘Nigger’ Horn. Aged 23 too, he had actually been born in England the day after the ship that had brought his family and two brothers from Australia had docked. One brother, K K Horn, would win the MC with the RFC. Following service with the Dragoon Guards, Nigger Horn had trained as a pilot and flown with 60 Squadron in 1917, at the same time as Bishop had been there. He already had six victories and had also won the MC. When forming 85 Squadron, Bishop had asked Horn to become one of his flight commanders, and he had agreed. By the time Mannock arrived, Horn had claimed two more victories.

Captain M C McGregor DFC, 85 Squadron, a New Zealander.

In Horn’s Flight was another experienced pilot, Lieutenant Malcolm Charles McGregor who came from Hunterville, New Zealand. He was 22 years old and had earlier served with 54 Squadron flying Sopwith Pups in 1917, and had gained one victory. He would go on to become a flight commander with 85, and win the DFC.

According to McGregor, Mannock’s appointment was a popular move. He was well known to all the pilots, who enjoyed debate and was never happier when discussing issues with a bunch of pilots. Unlike some leaders, he liked to share his thoughts and tactics with them, whereas some top aces tended to keep to themselves their secret of success. In his letters home, McGregor made frequent references to Mannock.

There had also been two Americans in the Flight, Elliott White Springs and Lawrence Kingsley Callahan. Both had been in 85 Squadron since May. Springs had later immortalised himself and Larry Callahan by editing and adding to the diary kept by a third American with the squadron, 25-year-old John McGavock Grider, from Arkansas. [1] Grider had been killed in action on 18 June, but the other two soldiered on, and both became decorated aces. Later, both moved to the United States Air Service, serving with the 148th Aero Squadron – Springs having left already, as mentioned earlier. Springs came from South Carolina and was approaching his 22nd birthday, while Callahan, from Chicago, was 24. According to Springs, it had been mooted that McCudden might be selected to command 85, but they had protested and instead asked for Mannock, as some of them had trained under him in England.

It is strange that when writing later about this change of commanding officer, Springs had noted that the squadron pilots were not keen on McCudden as: ‘He gets Huns himself, but he doesn’t give anybody else a chance at them.’ This remark seems more in keeping with what some thought about Bishop, whereas McCudden, as well as being a tremendous stalker of German two-seaters, had always promoted the Flight system of fighting, and was an excellent patrol leader.

Others in the Squadron when Mannock arrived were again a mix of nationalities. Alec Stratford ‘Bobby’ Cunningham-Reid had been in the Royal Engineers and was another original pilot. He had lost a brother in the RFC back in 1915. He too would become an ace and survive the war.

Lancastrian, Walter Hunt ‘Scruffy’ Longton was 27, and had already been decorated with the Air Force Cross for his work as a test pilot. Finally getting away from test flying he had been posted to 85, and would be among a very few WW1 airmen to receive the DFC and two Bars. He gained 11 victories and remained with the RAF post-war, only to die while taking part in an air race in 1927.

Another experienced pilot was George Clapham Dixon, a Canadian from Vancouver. He was 22 and his army service had been with the Highland Light Infantry. George had then become an observer with the RFC, flying in the back seat of Sopwith 11/2 Strutters with 43 Squadron, and with his rear gun had downed two German fighters. Following pilot training he had been sent to 85 where he would score two more victories before becoming a flight commander with Mannock’s old 40 Squadron, and raise his score to nine before being wounded in September.

Mick with some of his 85 Squadron pilots; (left to right): John Dymond, Mannock, -?-, Lawrence Callaghan, and Walter Longton.

John Davis Canning came from Waipukurau, New Zealand and had just celebrated his 21st birthday on 1 July. The son of a farmer he came to England and joined the 4th North Staffs Regiment, transferring to the RFC in March 1916. He had already seen much action, firstly with 19 Squadron, flying Spads, then 48 Squadron, Bristol Fighters, and then 85, which he joined on 27 June. He would become a flight commander before returning to England in October 1918.

Others were Lieutenants John Dymond, another American, J C Rorison, who had arrived in June, Arthur Hector Ross Daniel, from South Africa, aged 26, and C B R MacDonald, another Canadian. Charles Beverley Robinson MacDonald was the son of Lieutenant-Colonel A C M MacDonald DSO. After service with the Canadian REs, he moved to aviation and had actually been with 74 TS in February and March 1918, so had already met Mannock. He joined 85 in May 1918 and despite a slight wound the day before Mannock was killed, became a flight commander and remained with 85 till the Armistice.

Douglas Carruthers came from Kingston, Ontario and was 26. A student at Queen’s University in his home town he had joined the RFC in June 1916, and flown as an observer briefly before training as a pilot. He had gone to 29 Squadron in April 1917 but was hospitalised before the month was out. Joining 85 in March 1918 he soldiered on until made a flight commander with 24 Squadron in October.

Edward Cecil Brown, 23, came from Dartford, Kent and had been an engineering student for three years before taking a commission into the Royal West Kent Regiment. Transferred to the RFC in August 1917 he joined 85 in March 1918. He did not survive the war (shot down by AA fire, 18 October 1918).

Gordon David Brewster MC, aged 21, hailed from Forest Hill, SE London. He had won his Military Cross with the 3rd Regiment of the Bedfordshire Regiment, and despite the rank of captain, had moved to the RFC in December 1917, dropping rank to second-lieutenant. He arrived on 85 in mid-June. Colin Frank Abbott from Palmers Green, north London, wouldn’t celebrate his 21st birthday until a month after the Armistice. A junior draughtsman in London till late 1915 he had joined the RFC as 10410, air mechanic 2nd class. After service overseas he returned in August 1917 to learn to fly and came to 85 in February 1918. As noted in the Prologue, Donald C Inglis DCM, hailed from New Zealand, was 25 years old and had won his Distinguished Conduct Medal at Gallipoli with the NZ artillery.

Another recent newcomer to the Squadron was John Weston Warner, from Boston Spa, Yorkshire. He had claimed his first victory on 29 June and by mid-August was to achieve seven more and be awarded the DFC. He was still only 19 when he was shot down and killed by a Fokker DVII on 4 October.

William Edward Wittrick Cushing was the Squadron’s recording officer. At 26 he had a wife in Swaffam, Norfolk, and had been a school master for the last year of peace. An officer with the 9th Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment, he became an observer in BE2c machines with 13 Squadron, completing his time at the front in May 1917. He had become an RO and joined 85 in May 1918. Peter Rosie was the squadron engineering officer. At 42 he was the oldest officer in the unit and had a wife in Upper Largo, Fifeshire, Scotland. For ten years before the war he had been branch secretary to the Scottish Provident Institution, Dundee. Despite his age he joined the colours and became an officer with the Leicester Yeomanry, attached to the 3rd Reserve Battalion of the Hussars. He had then joined the RFC in August 1917. His engineering experience is not known, but he held down the job from once posted to the embryo 85 Squadron in November 1917, till the war’s end. He was responsible for taking numerous photographs of squadron pilots while with 85, for which historians are thankful.

Once he had settled in, Mannock chose SE5a E1295 with a 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper engine. It had been brought from No.1 Air Issues Depot (AID) on 20 June 1918 and while it had been worked on by the mechanics to bring it up to 85’s standard, it had only been test flown thus far and not operationally. Mannock would fly this machine for the whole of his short time with the Squadron. As far as we can tell, no photograph of this machine has ever been seen, so its markings are unknown, other than it no doubt had the white hexagon that identified 85 Squadron, on the fuselage sides aft of the roundel. Nigger Horn, who had done much to hold the Squadron together during Bishop’s period and while awaiting Mannock’s arrival (while George Baker did the paperwork), had taken over Bishop’s SE5, No. C1904, and flew it for the rest of his time on the Squadron. This machine was declared unfit for further service by late September due to its long service, and flown back to England was struck off charge in October. It had been marked with the letter ‘Z’, painted both beneath the cockpit and on the upper starboard wing. One has to wonder if Mannock used the letter ‘Z’ on his machine too, and that Horn’s C1904 was re-marked with the letter ‘A’, so as to denote the leader of A Flight. Squadrons that used letters on their aeroplanes generally tended to use the letters A to F, for A Flight, G to N, B Flight, and M to R for C Flight. Letters after R would go to spare machines (at least one squadron used ‘S’ for its CO), or to fill in if a squadron’s complement exceeded the normal number of 18.

85 Squadron’s SE5s just prior to Mannock’s arrival as CO.

Whatever Mick Mannock’s state of mind upon his arrival back in France, he showed little sign of having a problem as he arrived at 85 Squadron. Several pilots have recorded that soon after he took over he had all the pilots in his office and outlined what he thought they should do. Although Springs’s book War Birds, referred to above, is a fictionalised account of Grider’s diary, he remarked on this meeting:

‘Mannock has arrived to take charge all rigged out as a major with some new barnacles on his ribbons, and he certainly is keen. He got us all together in the office and outlined his plans and told each one what he expected of them. He’s going to lead one flight and act as a decoy. Nigger and Randy are going to lead the other two. We ought to be able to pay back these Fokkers a little we owe them.’

The Fokker DVIIs were now a force to be reckoned with and 85 and Mannock got amongst some on 7 July, in their first action together. The Squadron mounted an Offensive Patrol to the area around Doulieu, between Merville and Bailleul. Mick led three SE5s as the bottom section, with Randall’s Flight above, and Horn giving top cover. At 08.15 Horn saw seven Fokker biplanes at 18,000 feet above them, and he led the patrol towards the lines in a climb, the Fokkers following. The leading two Germans started a dive as Horn turned into them, and the other Germans joined in.

As the dog-fight began, Horn spotted two DVIIs get behind ‘Scruffy’ Longton. Horn went after one, his fire sending it down in a spin. He then got on the tail of the other and after giving it good bursts, followed it down to 8,000 feet at which point the Fokker’s wings ripped away and the wreckage crashed near Steenwerck. Heading back into the mêlée that was continuing to the west of him, he dived into it and saw Longton despatch another DVII, seeing it crash at position, Sheet 36A F.14.

Longton had earlier attacked a DVII that was closing in on another SE5 but moments later he had those two other Fokkers right behind him. He saw Horn intervene and shoot down the first one, and as Horn tangled with the other, Longton got in behind another, firing half a drum of Lewis into it from close range. The German machine went down in a slow spiral from 2,000 feet but then he had to pull out to engage another DVII. Horn, however, saw it hit the ground.

Major Edward Mannock DSO MC, Officer Commanding 85 Squadron 1918.

John Warner had a go at another DVII after the initial clash, climbing up beneath a Fokker that he saw 500 feet above him. He missed with his first burst and the German pilot shoved his nose down and dived. Chasing after it, Warner fired again from both guns but was unable to catch it nor see if the pilot survived the dive into some low ground mist.

Mannock meantime, still below Horn’s Flight, observed the encounter, and began to let down as the battling aircraft drifted lower to around 7,000 feet. He was attacked by a red-bodied DVII, but its pilot seemed to lose control and fall away. Mannock followed, firing as his sights came to bear and watched until it went vertically into the ground about a mile east of Doulieu.

Down now to around 1,500 feet, Mannock climbed for about 1,000 feet and saw an SE5 being engaged by two enemy machines. Going after the one nearest the tail of the SE he fired some 30 rounds from each gun and the DVII went into a spin at about 1,000 feet and he lost sight of it but felt sure it must have crashed. Longton later confirmed seeing the first one go down.

In their first air action under the new ‘boss’ four DVIIs were claimed destroyed, two more out of control, and another driven down. Unfortunately there does not appear to be any losses in German personnel this date, even though one of the DVIIs was seen to shed its wings. Nevertheless it was a boost for the Squadron, and Mannock’s tactics seem to have been successful, even though it appears to have worked in reverse, with Horn being attacked above while still covering Mannock’s boys below.

On the 9th the great Jimmy McCudden was killed. This was a bitter blow to Mannock and undoubtedly made him think yet again of his own mortality. It was no consolation to learn that McCudden had not fallen in combat, although by the same token it was galling to know that a simple flying accident had robbed the RAF of one its greatest air fighters. Who knows what he might have achieved had he lived? A future career within the service seemed assured.

Had McCudden, if Springs remembered it correctly, been given command of 85 Squadron, he would not have been flying out to his new command, 60 Squadron, at Boffles, on this July day. If he had not become lost and landed at Auxi-le-Château to ask for directions, he wouldn’t have crashed after he had taken off again and his engine packed up. He then made the fatal error of turning back towards the airfield, stalled, and crashed. He lies buried in nearby Wavens cemetery.

On 10 July Longton knocked down a Hannover two-seater, aided by Lieutenant Dymond. This occurred at 06.50 and after the initial attacks, the propeller stopped and the two-seater glided down to crash at Sheet 36A L.7.

On the 13th, George Dixon, now a flight commander as George Baker was tour-expired, led an evening patrol and ran into several Fokkers and Pfalz Scouts near Armentières. He was leading a top cover section of three SEs (himself, Callahan and McGregor) and he led them down onto four Pfalz and his opening burst of 50 rounds sent one down in a spin. As the engagement now commenced in earnest, he attacked another Pfalz and saw it turn onto its back and go down vertically to crash near the canal to the east of the town, confirmed by Larry Callahan.

Callahan himself dived into the German fighter formation and his fire also sent one of the enemy down out of control (a Fokker) and he saw it crash near the town, as well as seeing Dixon’s victim crash nearby. These machines may have been from Jasta 20, who had three pilots shot down this day, whilst claiming one SE5 down by the front lines. 85 Squadron lost Lieutenant William Scott Robertson south-east of Armentières, who was killed. Bill Robertson came from Middlesborough, Yorkshire. He was brought down by Carl Degelow, leader of Jasta 40s.

There was a big fight early on the 14th. Mannock, with Randall’s Flight, was flying north-east of Merville at 08.35 and encountered a mixed bag of German fighters – Fokker biplanes, Pfalz and Albatros Scouts. Mannock dived from 10,000 feet on the leader of two fighters but disengaged as he observed a Fokker – marked with a white horizontal swastika on its fuselage (in those days a good luck symbol) and a black and white tailplane – on the tail of an SE. He fought this machine down to 1,000 feet and watched as it crashed. Randall was able to confirm this.

The SEs now began to split up, but Randall got into a favourable position on a Pfalz with a yellow tail and fuselage, firing several bursts from both guns until, just north of Armentières, it went down and crashed. Seeing then Mannock’s Fokker crash, he began to regain lost height.

Group of 85 Squadron pilots. Dymond and Longton sit in the front, while behind them in the RFC ‘maternity’ jacket and pipe, is Donald Inglis DCM, who would accompany Mannock on his last flight. To his left is G C Dixon with Spencer Horn almost out of shot. Behind Dixon is E C Brown, while behind Inglis is Lt Carruthers.

Scruffy Longton had also dived into the German formation, following one as it zoomed away. He got in two good bursts at close range before his Vickers gun jammed. With his Lewis drum now empty, he could not follow up on his attack, but he then saw Randall in his SE5 marked with the letter ‘H’, chasing it over Armentières.

Lieutenant Rorison was flying with Dixon’s Flight nearby and initially got onto the tail of a Pfalz as it streamed away from the main fight. Despite several bursts, he lost it as the battle spread around him, then another German dived on him from above. He turned quickly and engaged this EA (a Fokker) firing several bursts from close range while having descended to around 1,000 feet. The Fokker dived earthwards and later he saw debris on the ground in a field south-west of Estaires. He also noted that he had seen Dixon attack a whitetailed Pfalz and thought it was starting to go down out of control.

Some minutes after this scrap broke up, Mannock spotted a green mottled two-seater and went into the attack. Both Mannock and the German crew opened fire at the same time, and bullets slashed into Mannock’s machine. As they passed by each other, the German turned north, began to side-slip, then turned over about a mile east of Merville and went down. Mannock watched as this two-seater made a reasonable landing down wind on some rough ground, but noting that it did not break up, and assumed its engine had been damaged in their head-on encounter.

Longton meantime, had also spotted a two-seater, an Albatros C. He had cleared his jam by now and replaced his empty Lewis drum and together with Randall, dived on the German, getting in several good bursts at close range. At 200 feet this second drum was emptied so he zoomed up to replace it once more. Randall observed the two-seater continue down and crash.

Randall had already had a brief encounter with a Hannover CLIII after the fighter battle, but it quickly made off east, followed by a quick burst from the SE5’s guns. Randall then saw the Albatros two-seater with Longton’s ‘K’ attacking, but after a quick burst, both of his guns jammed, so had to follow Longton as he proceeded to despatch the Albatros on his own.

Some of the Germans encountered were once again from Jasta 40s. Carl Degelow claimed an SE5 in this fight and other pilots also made claims but 85 only lost one pilot, Second-Lieutenant H N Marshall, who was brought down and made a prisoner. It was Degelow’s 10th victory and some minutes later he made it 11 by claiming an SE5 of 64 Squadron too.

This action resulted in another four claims, plus a two-seater forced to land. Once again there are no positive German personnel losses on the fighter side and it is often difficult to pinpoint two-seater crew casualties. Nevertheless, 85 were no doubt again well pleased with their efforts under Mannock’s leadership.

There was a bit of a lull in activity after the 14th with a lot of low cloud over France, rain and even thunderstorms. When this cleared on the 18th, strong wind hindered operations, and on the 19th the Germans kept away from the front. Most of the land action was taking place further south on the French front, the Jastas in the north merely keeping a watch along the trench lines.

However, Mannock claimed a victory on the 19th during another early morning patrol to the Merville area. At 08.35 he spotted an Albatros two-seater flying well over the lines near Estaires but heading west. He led the patrol to the north-east in order to get between the German and his home territory, then swooped round and down to attack the German head-on. Once within an acceptable distance he began firing, blasting 80 rounds from both guns down to point-blank range, from the front and then, having shot below the two-seater, from below. Almost immediately the Albatros caught fire and dived leaving a flaming trail, and crashed, still burning, at map reference, Sheet 36A.K.34b – the feat being witnessed by all members of the patrol.

This was a machine from Flieger-abteilung Nr.7, who lost a crew at Merville this date. The two men were Unteroffizier Alfred Hartmann, from Castrop, north of Dortmund, aged 21, and Leutnant Eberhard von Sydow, 20, from Halberstadt, south-west of Magdeburg, the latter being buried at Seclin.

The maestro scored again the next morning on what is described as a special mission and Offensive Patrol. The patrol was over Salome, east of La Bassée at 11.15, exploding AA fire attracting Mannock’s attention to an enemy machine. He was not sure of the type, although in fact it was another Albatros C XII, and again from FA7. The Albatros company had given their type C XII two-seater a rounded fuselage, much like that of their fighters, rather than the old flat-sided ones, which may be why Mannock thought it different.

In any event, the patrol dived from 10,000 feet from the east and again Mannock opened fire from head-on, his favourite position against two-seaters, so as to avoid detection and fire from the observer in the rear. Shedding pieces of torn fabric, the Albatros plummeted down, its pilot no doubt wounded. At 4,000 feet the machine seemed to flatten out, turned north, then vertically to the south and crashed near Illies, north-east of La Bassée, after some moments during which it seemed to float before finally crashing.

Continuing the patrol, an hour later, while south of Steenwerck, three Fokker DVIIs, with black fuselages, checkered wings and white tails, hove into view at 10,000 feet near Merville. Mannock led an attack from the east while others approached from the west. Following a close action combat, Mannock’s fire sent one Fokker down out of control and trailing smoke, confirmed by Larry Callahan. More pressing encounters followed so nobody was able to see if the machine crashed. (While some German aircraft did have wings painted in a checkered fashion, it is more likely to have been lozenge fabric which they used on their aircraft increasingly in 1918.)

The FA7 crew, who both died in the first action, had been Unteroffizier Adolf Raths, aged 28, from Dalliendorf, and Leutnant Gross, who, if his name has been spelt correctly, has not yet been further identified.

Gwilym Lewis with 40 Squadron, had just been notified of the award of the DFC – the RAF’s equivalent of the MC. He was about to go home on rest, and in his diary for 21 July he mentions a party in his honour that had occurred the previous evening:

‘Last night I had my farewell dinner. Mick Mannock was there with two of his flight commanders, and also several members of the Brigade. It was a great binge. I feel awfully rotten leaving my priceless Flight. I am awfully pleased that I have had the luck not to lose a single fellow while I have been here, though two went down when I was on leave. Mac [McElroy] I believe thinks it is rather a bad sign, but I am truly thankful! Anyway, before he arrived B Flight led in the number of Huns from the new year. Now I tell Mac that while he counts the number he has shot down, I count the number I see. I believe he is still ahead! He has reached 47 now!’ [1]

Gwylim Lewis DFC and George McElroy MC DFC, 40 Squadron in 1918. Mac was a particular friend of Mannock and was killed within a week of Mick’s own demise.

It was Mannock again who added to 85’s laurels, on the 22nd. Shortly before 09.30 am, leading a patrol, he ran into five Fokker Triplanes near Steenwerck at 14,500 feet. These machines attempted to attack the SE5 patrol from behind, but Mannock’s keen eyes had seen the danger, and pulled out of trouble. Part of the Flight now flew to the north-west, while the top three went to the north-east. This was another tactic introduced by Mannock, splitting the patrol in two in order to ‘surround’ the enemy, or at least, give him two groups of SE5s to watch out for, one on each side.

Mannock also began to climb towards Lille where the Triplanes were now headed, and intercepted them over Armentières. He fired tentatively at several of the three-winged fighters, following one into some clouds and on coming out the other side, and down to around 11,000 feet, shot the tail off it, confirmed by Lieutenant Dymond.

This seems like a certain victory, as Triplanes without a tail did not generally survive from a height of 11,000 feet! It was a day of heavy fighting and the Germans did lose a handful of fighter pilots. The most likely candidate for Mannock’s victim would be Vizefeldwebel Emil Soltau of Jasta 20. He was reported lost over Gheluvelt, although this seems a bit too far north to be certain. Mannock noted the Dr.Is had brown and green mottling, and Jasta 20 were known to have brown fuselages. Soltau was 26 and came from Barsbüttel.

Ira Jones and Mannock often spoke to each other on the telephone. Jones had taken over Mick’s A Flight after he had left. They would each try to pull the other’s leg and Mick was becoming even more fatalistic about his future. In some ways he was masking this by over-emphasising men and machines going down in flames, as if obsessed by this terrible way to die. Generals and politicians at the top still doggedly kept to their decision not to supply parachutes to airmen – in case they became less aggressive and baled out if in trouble! Balloon observers had them, so why not pilots and observers in aeroplanes? It would make them more aggressive, not less, knowing that if things did go wrong, at least they had an escape route. Men like Jones and Mannock had seen many friends and comrades die a needless death in the fiery death-trap of a burning aeroplane. Jones wrote in his diary for the 24th, after having increased his own score to 26 with three DFW two-seaters shot down that day:

‘I phoned Mick to pull his leg. He retaliated to my banter by asking me to have lunch and tea with him tomorrow to explain my methods. Silly ass!

‘He told me he had shot a Tripe’s tail off a couple of days ago over Lille. Some lad is our Mick. I often wonder whether he will live to get his century. Personally, I can’t visualise a Hun getting him down, unless by accident, although it does look as if death cometh sooner or later to all the star fighters. Mine will come like the rest, I suppose. Well, I shall be quite ready. My only regret will be leaving my dear old mother behind to mourn me. Mothers have a tough time in wars.’

Mannock’s boys had had a good day on the 24th, with another four fighters claimed as destroyed and another out of control. They were again out in two layers, the lower Flight acting as decoy. Once they found enemy aircraft, the top Flight attacked from the east, in Mannock fashion.

It was mid-morning, north-west of Armentières. Mac McGregor was leading the top Flight of four SE5s and manoeuvred east of the Fokker DVIIs they had spotted as they edged towards Randall’s lower bunch. Mac dived and opened fire on one DVII from point blank range. The German, stung by the surprise attack, zoomed away and then began to go down in a wide spiral with its propeller stopped. Mac then saw another German behind the SE of Lieutenant D C Inglis, and attacking this at close range, saved the New Zealander, and was able to see his target go down and crash.

Lieutenant O A Ralston, another American with the Squadron, also went down on the six Fokkers as they began to head for Randall’s men. He fired at close range at a DVII from one side, then attacked another from the rear. The second machine went down, diving over the vertical and Orville Ralston followed it to 4,000 feet then pulled round and watched it hit the ground.

Snowy Randall had seen the Fokkers above and had headed north towards Dickebusch, then south-east, losing height all the time. Meantime he could see McGregor’s section coming round to attack from the east, then dive. One DVII started to fall, trailing smoke and Randall went after it, firing with both guns. It continued down to crash.

Longton was also in the lower section and saw the approaching Huns and as the attack developed, he turned and clamped himself onto the tail of a yellow-coloured Pfalz Scout. His fire caused it to go down and crash, followed quickly by another crash, the Fokker downed by McGregor.

Mannock was not on this patrol, but it is obvious his pilots had learnt this lessons and followed his doctrine to secure another victory over enemy fighters. His three flight commanders, Horn, Randall and McGregor were more than competent to lead the patrols and give Mick a rest. Whether he would take it would be another matter.

Jones accepted Mannock’s offer of a visit on the 25th, a showery day with enemy activity down to a minimum. Down south the French front remained busy. Jones took Mick’s old wingman, Clem Clements with him. Jones wrote in his diary:

Captain A C ‘Snowy’ Randall, 85 Squadron.

‘On the afternoon of the 25th, Clements and I went over by car to St Omer Aerodrome to spend the afternoon and evening with our idol and friend. As ever, he was the personification of liveliness in the Mess. His pilots also were in high spirits; their successes over the enemy and their happiness as a family made them so. Whomsoever we spoke to, we heard little else but talk of their offensive patrols and of Mannock’s wonderful leadership. The morale of the Squadron had reached its peak. The enemy was spoken of as so much dirt. Mannock was delighted.

‘Whilst we were having tea on the grass outside the Mess, a couple of very pretty VAD nurses from the Duchess of Sutherland’s hospital, located nearby, arrived to have tea with Mannock. This pleasant feminine touch added considerably to the enjoyment of the meal. The conversation naturally veered round to Hun-strafing, and as Mannock was explaining, amid roars of laughter, what it felt like to be shot down in flames, he suddenly said to a little New Zealander who was a comparatively new arrival: “Have you got a Hun yet, Inglis?” “No, Sir,” was the shy and almost ashamed reply. “Well, come on out and we will get one.”

‘Rising and asking to be excused for “a few minutes”, off he and his happy comrade went towards the aerodrome. With their machines ready to take off the leader gave the signal to taxi out, and in a few seconds he was in the air. His young companion, however, suddenly discovered to his dismay, that the elevator wheel of his machine was jammed tight, and on examination it was found that the machine would not be able to fly after all.

‘Mannock circled once, then realised that Inglis was not going to join him, and set off alone for the lines. While he was away, the young pilot cursed, swore, worried, and walked up and down in front of the hangars impatiently waiting for the Master’s return, secretly fearing he might not. Nearly two hours later an SE with a red streamer glided gently into the aerodrome, and young Inglis was happy once again. When he told Mannock what had happened, the mechanic was severely reproved for his carelessness, but as he was a good man, no disciplinary action was taken. The disappointed pilot was told not to worry, and that he would be taken out at dawn the following morning.’

Accompanying his friend to his hut, Jones continued:

‘Once inside, I asked him how he felt; he then frankly told me that he thought that he would not last much longer. Suddenly he put his arms upon my shoulders, and looking me straight in the eyes with a suggestion of a tear in his, he said in a broken voice: “Old lad, if I am killed I shall be in good company. I feel I have done my duty.”’

Clements, however, did not notice any problem with his friend, and amateur air historian Douglass Whetton, recorded in an article, that Clements had told him:

‘I do not recall that he was depressed or in any way out of sorts. On the contrary he was quite cheerful, and did not mention in my hearing any morbid thoughts about being shot down.’

In the same article, Whetton quoted Keith Caldwell as saying that at this time Mannock was at the top of his form.

Mannock’s victory score by a reasonable count on the morning of 26 July 1918 stood at approximately 60. According to most observers he was now living on his nerves, but to many others he was still the consummate fighter pilot, keen to get the war won, and although not what one might call a ‘born killer’, he had a burning hatred towards all Germans who had inflicted this mighty hurt and slaughter on civilisation.

Just as one might speculate what might have happened had McCudden not lost his way and made that extra landing, one can also wonder what might have occurred had Inglis’s SE5 not have had that mechanical failure the previous afternoon. Would they have found a Hun for the New Zealander? If they had, Mannock would not be taking off at first light on this morning so as to escort the youngster out, and consequently, would not have met his end. At least, not on the fateful 26th.

The facts of this, Mannock’s last sortie, are clear and well known. We will quote from Donald Inglis’s combat report rather than paraphrase the events. The sortie was listed as a special mission, in other words, not an offensive patrol, or a line patrol, or an escort job, but a one-off operation. Mannock led off in his E1295, Inglis flying in E1294. They headed for the front line, hoping to catch either an early German recce machine, or a trench-strafer. Perhaps even an early fighter pilot having a stab at the British balloon lines. They came across a two-seater, and as far as Inglis was concerned, its actual type could not be defined. He later wrote in his report:

‘While following Major Mannock in search of two-seater EA’s we observed an EA two-seater coming towards the Line and turned away to gain height, and dived to get east of EA. EA saw us just too soon and turned east. Major Mannock turned and got in a good burst when he pulled away. I got in a good burst at very close range after which EA went into a slow left hand spiral with flames coming out of his right side. I watched him go straight into the ground and go up in a large cloud of black smoke and flame.

‘I then turned and followed Major Mannock back at about 200 feet. About half way back I saw a flame come out of the right hand side of his machine after which he apparently went down out of control. I went into a spiral down to 50 feet and saw machine go straight into the ground and burn. I saw no one leave the machine and then started for the line climbing slightly; at about 150 feet there was a bang and I was smothered in petrol, my engine cut out so I switched off and made a landing 5 yards behind our front line.’

The action had taken place south of Lestrem, south-east of Merville, not far from Pacault Wood. The German machine was from Bavarian FA292(A), its crew perishing in the crash. They were Vizefeldwebel Josef Hein and his observer Leutnant Ludwig Schöpf. The Germans gave the crash position as La Croix Marmuse (some way east of the village of Pacault). Hein came from Dortmund and was 24 years old. Schöpf also was 24 and from Pfaffenhausen, south of Ulm. Fleiger-abteilung 292(A) made the following report on their loss:

‘On 26 July 1918 the crew of Vfw Hein and Ltn Schöpf (DFW CV 2216/18) left at 5.45 am [04.45 British time] on an Artillery Observation Flight. Owing to low cloud they flew at low altitude. At 6.39 am [05.39 British time] they were attacked by an enemy scout which dived on them from the cover of clouds. During the combat the DFW was shot down in flames near Croix Marmuse [sic], south-west of Lestrem.’

A report by the 55th German Army Corps noted:

‘At approximately 7 am a German aircraft was shot down by two British airmen in the area of Colonne [sic]. Both Englishmen were shot down by machine gun fire, the first aircraft, on fire, crashed in the locality of the 100th Infantry Regiment; the second aircraft fell between the lines. The pilot of the first aircraft is dead, the fate of the second pilot is unknown.’

The graves of Mannock’s victims from his last air fight on 26 July 1918, Ltn Ludwig Schöpf and Vfw Josef Hein, of FA(A)/292. Billy-Berclau German cemetery, north of Lens.

Today both German airmen lie in Billy-Berclau cemetery, to the south-east of La Bassée, an extension to the town cemetery, at the rear of the German grave markers in the top left-hand corner, the crosses numbered 7/321 and 7/331.

It has always been assumed that Mannock had been foolish in following down his last victim, thereby putting himself in range of ground fire. He invariably berated others for doing so, and continually warned against this stupidity. We shall, of course, never know why he did so on this occasion, but the fact remains that he did. But was there another motive? It may well be that he intended to shoot-up enemy trenches, or the German troops he knew to be in the northern half of Pacault Wood.

This had been done before, not the least by a Camel pilot with 4 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps. On 22 July – just four days earlier – Lieutenant R Moore had been part of a two-man patrol and at around 16.15 that afternoon, he had shot down a German two-seater near Pacault Wood, and had likewise pursued it earthwards. Meantime, Moore’s companion, Lieutenant O B Ramsey had dived down and amused himself by firing into the Germans in the Pacault Wood trenches who were watching the incident.

Then, on the 28th, just two days after Mannock’s fall, another 4 AFC Camel pilot, Lieutenant M T G Cottam, led five aircraft to low-bomb Lestrem. Returning to the lines, these pilots flew over Pacault Wood and loosed-off 1,400 rounds into the trenches there.

Meantime, 85 Squadron’s equipment officer, Lieutenant Rosie, had been sent out to try and retrieve the SE5 flown by Inglis. This proved impossible as Rosie recorded in a memo to No.11 Wing HQ:

I personally made an endeavour with a party of men to salve the above machine last night. I got to within 600 yards of its position, but owing to very heavy shell fire on the only available road, it was quite impossible to reach machine without serious loss of life. I am getting in touch with the O.C. Infantry Unit near the spot with a view to finding out present condition of machine.

| In the Field | P Rosie |

| 27.7.18. | Lieut. |

| Equipment Officer, | |

| For O.C. No.85 Squadron, R.A.F. |

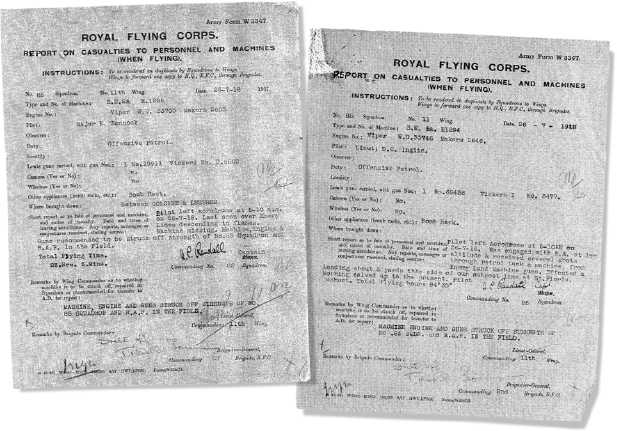

Captain Randall had already sent off an Army Form W3347 for each missing machine to Wing Headquarters requesting the two missing SE5s be struck off squadron strength and with the agreement of the Wing CO, Brigadier-General T Webb Bowen, the brigade commander, duly concurred a couple of days later.

[1] War Birds; Diary of an Unknown Aviator, George H Doran & Co, 1926.

[1] Actually 44 as at this date.