The State: Governing the Market 4,000 Feet Below

The community of some 350 residents had long gloried in what they called a “piece of heaven.” The neat, modest homes faced Crawfish Stew Street on one side and a canal on the other, leading to the bayou and extraordinary vistas of wide-winged water birds swooping gracefully from water to tupelo and cypress. Nearly everyone had a boat, knew the good fishing spots, got on with their neighbors, and enjoyed a good crawfish boil. Mike Schaff had said of his Bayou Corne neighbors, we’re nearly all “Cajun, Catholic, and conservative, predisposed to the Tea Party.” But among them, Mike Schaff was the most ardent—he had joined the Tea Party, gone to meetings, spoken out. Raised in a shotgun house in the sugarcane field we had driven through together, and a lifelong employee in oil, Mike wished to feel himself in a nearly wholly private world, one as far as he could get from government taxes and regulation. But what would happen, I wondered, if a community of people such as Mike suffered a sudden catastrophe that, beyond any doubt, could have been prevented by respect for government regulation? What was his understanding about the state? Could I see why he felt as he did? These questions had led me to Mike Schaff and the Bayou Corne Sinkhole.

Because just that catastrophe occurred in August of 2012. First, neighbors noticed tiny clusters of bubbles on the surface of the water. Had a gas pipe traversing the bottom of the bayou sprung a leak? A man from the local gas company checked and declared the pipes fine. At the same time, Mike recalls, “We smelled oil, strong.” Then he and his neighbors were startled by the shaking and rumbling of an earthquake. Since earthquakes had never before occurred in this part of Louisiana, one woman imagined a “garbage truck had dropped a dumpster.” A single mother of two living in a mobile home a mile from Bayou Corne thought her washing machine was on, then remembered it had been broken for months. A man was eating dinner from his TV dinner tray when it began to shake. As Mike recalls, “I was walking in the house when I felt like I was either having a stroke or drunk, ten seconds; my balance went all to hell.” A while later, he noticed a jagged crack zigzag across the concrete underneath his living room carpet. Lawns began to sag and tilt in strange directions.

Not far from Mike’s home, the earth under the bayou was beginning to tear open. As if a plug was pulled in a bathtub, a hollow “mouth” of a crack in the bottom of the bayou began sucking down brush and pine from the surface of the earth. Majestic, century-old cypress trees crashed down in slow motion and were dragged sideways into the bubbling water, drawn down into the gaping mouth of a sinkhole. Down went bush, grassland, and even a boat. An oily sheen had appeared on the surface of the water, and to prevent its spread, two cleanup workers were called in to cast booms around the oil not far from the sinkhole. To do this, the two men tied their boat to a tree, standing in it to do their work. But the tree began to tilt and drift. The workers were rescued in time but their boat disappeared into the sinkhole.

In the following days and weeks, polluted mud was thrown back up onto the surface of the water in a weird and terrible exchange of pristine swamp forest for oily sludge. Oil oozed to the surface of the water, and natural gas emanated here and there from land and water. “During a rain, the puddles would shine and bubble, like you’d dropped Alka Seltzer tablets in them,” Mike says. The sinkhole grew. First it took the area of a house lot, then a football field. By 2015, the sinkhole stretched over thirty-seven acres. Then the gassy sludge had also infiltrated the aquifer, threatening the drinking water.

Residents noticed that the main road into the community began to sink and feared it would cave in. Levees along the bayou, originally built to contain rising waters in times of flood, had also begun to sink, threatening to extend the sludge beyond their boundaries.

The Cause and the Blame

The culprit in this strange accident was a Houston-based drilling company, Texas Brine. As its name suggests, Texas Brine drilled for intensely concentrated salt, which it sold to manufacturers of chlorine, and which is also useful in fracking. It drilled down 5,600 feet beneath the bayou into an enormous underground geological formation called a salt dome—unseen and fairly common in the Gulf. In a highly risky maneuver—disregarding the advice of their own consulting engineer, and with the okay of a government official also aware of the danger—Texas Brine drilled underneath Bayou Corne. On the books were regulations that were disregarded by both company and state.

The drill accidentally pierced a side wall of a teardrop-shaped cavern inside the Napoleonville Dome. (The Napoleonville Dome is an underground block of salt, three miles wide and a mile deep, sheathed by a layer of oil and natural gas. It is well known to people in the area, but not much outside it, and private companies drill deep inside the salt to hollow out pockets, large and small, some shaped like straight posts, others like mushrooms or cones. Inside them, companies store chemicals.)

When the drill pierced the side of one cavern inside the dome, a catastrophe slowly unfolded. Weakened, one wall of the cavern crumpled under the pressure of the surrounding shale. Water was sucked down, drawing trees and brush with it. Oil from around the dome oozed up. The earth shook. In places its surface tilted and sank.

The disaster drew public attention to a vast underground world—previously unknown to me—and raised important questions about how a free-market economy in a highly regulation-averse culture was handling toxic chemicals in some 126 salt domes in Louisiana—plus more offshore—stored from 3,000 to 18,000 feet beneath the surface of the earth.

In the Napoleonville salt dome, a lively commerce was going on. Petrochemical companies own fifty-three caverns and some seven more companies rent space in them. These are valuable, large storage depots for the many chemicals used in oil drilling, fracking, and plastic manufacturing. Texas Brine rents six caverns. Dow and Union Carbide owns others into which they have pumped fifty million gallons of ethylene dichloride (EDC). While it surprised me to learn how far down into the earth free enterprise went, such underground storage systems have long been accepted practice in the Gulf region; the National Petroleum Reserves have themselves long been stored in a similar way.

Still, I wondered, if one company could drill one hole in one cavern and cause a sinkhole that made methane gas bubble in rain puddles, what else could happen, with earthquakes now in motion, and other EDC-filled caverns nearby—all in a culture in which the very idea of regulation has fallen into very low esteem?

My keyhole issue had taken me 4,000 feet down into the earth. And following it down the hole was the Great Paradox: the Tea Party feared, disdained, and wanted to diminish the federal government. But they also wanted a clean and safe environment—one without earthquakes sending toxins into aquifers or worse. But here was the rub: didn’t America need a culture of respect for the safeguarding of such concerns? Don’t we need government workers—ones with no skin in the game—to do the safeguarding? How did my good, bright, and caring friend Mike Schaff and others put these two desires together?

The Minimal State

Dapper in a blue shirt and khaki pants, Governor Bobby Jindal steps down from his helicopter and strides rapidly toward a cluster of waiting officials and restless refugees from the Bayou Corne Sinkhole, as it is now named. Many residents, seven months on, are still homeless, doubling up with relatives, living in trailers, motels, and campers. One couple had celebrated Thanksgiving in a twenty-four-hour Laundromat because they had nowhere else to go. Burly security men with close-shorn hair and dark glasses fan out around the governor. Hand outstretched, Jindal walks rapidly forward to greet officials and listens, head tilted, hands on hips, to their words. He moves toward a podium set in a green field not far from the sinkhole.

The earth had opened ominously on August 3, 2012. Four months later, on December 16, 2012, a resident posted on his Facebook page:

Where Are You Bobby Jindal?????

You were elected to be the leader of our State. . . . Bayou Corne/Grand Bayou . . . was declared a State of Emergency by your office on August 3rd [2012]. . . . There are mini earthquakes, methane, benzene and hydrogen sulfide being released into the community. This community has been through hell and back and is still living a nightmare. In my opinion and many others you have . . . done absolutely nothing helpful to this community.

Seven months after the disaster, on March 19, 2013, Governor Jindal visits the sinkhole for the very first time. He has helicoptered in from Baton Rouge, forty miles away—“it’s only a five-minute ride,” one disgruntled resident tells me—to address the gathering.

With a line of white-shirted officials behind him and a thin scattering of distressed residents, arms folded, facing him, Governor Jindal speaks rapidly and emphatically from a fact-studded script. The very pace of his talk conveys mastery, urgency, busyness, and, perhaps, avoidance. The state is doing all it can to help, he tells the gathering. He’s appointing an independent Blue Ribbon Commission. He’s on the case.

The governor finishes his prepared remarks and calls on local officials to speak, before finally opening himself to restless residents for questions. One resident asks the governor why he waited seven months to come the short distance. Noting that the governor announced his visit only at 9:00 A.M. of the morning he was to arrive at 2:00 P.M. the same afternoon, another asks why, after the seven-month delay, such short notice? Why was the meeting also set for two o’clock on a weekday when most people would be at work? Had the governor seen the sinkhole?

By now, the homes of 350 residents were part of a “sacrifice zone,” as officials called it. A geologist hired by Texas Brine had earlier explained to shocked residents that “nobody in the world has ever faced a situation like this.” Was a nearby cavern, still being drilled into, also in danger of collapse? When would the gas, the earthquakes stop? The Blue Ribbon Commission is looking into it, the governor says.

A Two-Beer Levee Job

To drive to Mike Schaff’s home, I turn right on Gumbo Street, left on Jambalaya, pass Sauce Piquant Lane, and park on Crawfish Street, opposite a two-story yellow wooden home. The street is deserted, the grass high. Planted around his yard are fruit trees—satsuma orange, grapefruit, mango, and fig—but the fruit hangs unpicked.

“I’m sorry about the grass,” Mike says as he greets me wearing an orangeand-red striped T-shirt, jeans, and boots. With the sweep of a muscular arm, he points to an unpruned rose arbor, “Just haven’t kept the place up.” Mike has set out coffee, cream, sugar, and a jar of peaches to take when I leave.

“This has been the longest six months of my life. To tell you the truth, I’m depressed,” he says. “Five years ago I moved here from Baton Rouge to live with my new wife,” he says, pouring us coffee. But “with the methane gas emissions all around us now, it’s not safe. So my wife has moved back to Alexandria and commutes to her job from there. I see her on weekends. The grandkids don’t come, either, because what if someone lit a match? The house could blow up.”

Mike sleeps uneasily. He has placed a gas monitor in his garage and checks it from time to time. “The company drilled a hole in my garage to see if there was gas under it. There was: 20 percent higher than normal.” He avoids lighting matches. He lives day to day among his cardboard boxes, keeping watch over his neighbor’s property and a wary eye on wandering feral cats.

The governor had issued an evacuation order for all residents of Bayou Corne, but Mike could not bring himself to leave. “I’m here to guard the place against a break-in—there’ve been quite a few—and to keep the other stayers company.” After a long pause, he adds, “Actually, I don’t want to leave.”

“Excuse this,” he says, pointing to a jagged crack in the cement to the side of a rolled-up carpet. “The earthquake caused that. We never had earthquakes before the sinkhole, or methane gas rising from our lawns.”

After coffee, Mike walks me to the edge of his backyard, speaking in the present tense as if his life is ongoing: “This is where we have neighbors in for crawfish boils.” Visible across the canal, and up and down it, are other patios with grills, yoo-hooing distance across. But now, he tells me, “It’s no longer Janet and Jerry. It’s no longer Tommy. It’s no longer Nicky and his wife. It’s no longer Mr. Jim.” He points around. “It’s Texas Brine, Texas Brine, Texas Brine, and Texas Brine. It’ll be eighty-eight weeks this Monday,” he continues. “As of now there’s me, Tommy, Victor, and Brenda, and that’s it.” Texas Brine has been negotiating prices to buy neighbors out.

It had been a close-knit community with a shared devotion to fishing, hunting, wildlife, and conservative politics. Married five years to his beautiful new wife—Mike’s third marriage, his wife’s second—this is the last situation he’d imagined being in. “We’re a close community here.” He gestures around as if to introduce me to invisible friends. “We have our own Mardi Gras, parties at Miss Eddie’s Birdhouse.” The husband of a neighbor, a birdlover, had built a structure to shelter birds, considered noisy by neighbors. After he died, his widow converted it into a party house with a Jacuzzi and strobe lights. “We help each other rebuild levees during floods. You got the two-beer levee job, or the four-beer one.” He laughs. “We love it here.”

Other Bayou Corne refugees I would interview said the same. One man named Nick showed more photos of children parading around the neighborhood in decorated bikes, neighbors in decorated golf carts, and boat trailers for the Mardi Gras Bayou Corne Hookers Parade, celebrants dancing in the street—some years to the music of a live band. “We used to have fishing tournaments. The winner was the one with the heaviest catch, and we ended up holding a fish fry.”

Even if government helped people—and he didn’t think it did much—government should never, Mike felt, erode the spirit of a community. He had grown up in a dense circle of aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents, all within walking distance from each other on the Armelise Plantation. Now in his sixties, Mike felt happy to live in a community as close and cooperative as the one he had known as a boy.

For a man who could lose himself for hours in the garage assembling a two-seater Zenith 701 airplane from a kit, and who described himself as “to myself,” such a community brought cheer. The sociability of Bayou Corne brought him out of himself. It wasn’t the simple absence of government Mike wanted, it was the feeling of being inside a warm, cooperative group. He thought the government replaced that.

His was also a love of place. Just as Mayor Hardey loved Westlake, Mike Schaff loved Bayou Corne. Just as Sasol was expanding onto Hardey family land, so Texas Brine had taken over Mike’s home. But there was a difference. Hardey’s family had been handsomely paid, his own home was unharmed, and he didn’t mind industry as a neighbor. But Mike’s home was in visible ruin and the community he loved was scattered to the wind—to Mississippi, Texas, and other parts of Louisiana.

Mike disappears into his boat garage and backs his boat out into the canal. I climb in. The boat sputters to life and putts out of the canal into the wider bayou. Swerving around dark stumps of dead cypress trees, we duck under strips of low-hanging Spanish moss, which look like fuzzy tatters of an old fur coat hang from cypress, tupelo gum trees, and swamp maples. We duck again to putt under a low bridge, then speed into a widening vista. “Around here you pull up bass, catfish, white perch, crawfish, and sac-a-lait—at least we used to. Now? They’re swimming in a methane bath.”

At a distance, we see a red, white, black, and yellow sign nailed to the gray trunk of a tupelo: “DANGER, KEEP OUT, HIGHLY FLAMMABLE GAS.” The reflection of the warning wobbles in the rippling water. Mike points to small concentric circles of bubbles, scuttling outward like small bugs. “Methane.”

Rumor, Panic, Blame

After the sinkhole, talk turned to blame, which ricocheted wildly from one thing to another. First Texas Brine blamed Mother Nature. Earthquakes were natural in this area, officials said, which wasn’t true. Then it blamed and sued Occidental Chemical Company, the company from which it rented space in the Napoleonville salt dome. Then Texas Brine’s insurance company blamed Texas Brine and refused to pay insurance. Then Texas Brine sued the insurance company. The legal wrangling expanded. Only 1,600 feet from the cave-in, Crosstec Energy Services rented an adjacent underground vault in the dome, filled with the equivalent of 940,000 barrels of butane gas. Wishing to continue business as usual, Crosstec sued Texas Brine on grounds that the cave-in had prevented them from expanding and led to the loss of storage contracts it could have made with companies wanting to rent. In 2015, Texas Brine sued yet another company, Oxy Petroleum, for $100 million for weakening the cavern wall by drilling too close to the cavern’s edge back in 1986 and so causing the disaster in 2012. And so it went.

Meanwhile, still doubled up with family in spare rooms, trailers, and motels, shell-shocked refugees commuted to work from temporary quarters, turning to each other by e-mail and to the Internet and television news for updates. Anxious rumors flew. Would the stored gas ignite, causing a firestorm? Would earthquakes break the walls of other caverns containing dangerous chemicals? One alarmed writer for the Denver-based website Examiner.com feared an explosion “with the force of more than 100 H-bombs like the ones in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Others called for calm and reason. Apparently wanting a break from the anxious talk, one man who’d stayed in his Bayou Corne home wrote on Facebook: “Took a break from painting patio furniture and caught eight of these li’l beauties [photo of fish] right from my pier in about an hour.”

Some contributors to a website called The Sinkhole Bugle blamed both the company and the government but aimed their deepest anger at the government. Dennis Landry, owner of Cajun Cabins of Bayou Corne, pointed out, correctly, that the state Department of Natural Resources “knew for months” that the Texas Brine well had integrity problems and didn’t tell local authorities. “I’m very upset about it. . . . I feel like I’ve been betrayed by the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources.” One man even described Texas Brine as the “fall guy.”

Moral Dirty Work

It was becoming easier to understand why energy refugees were so furious at the state government. First of all, it turned out that the secretary of the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources from 2004 to 2014, Scott Angelle, had known of the weak cavern wall but had given Texas Brine a permit to drill anyway. He had been transferred soon after the event to a different job and was now, to Mike’s horror, running for governor. (Angelle later lost.)

Indeed, the caverns had been casually regulated. Similar accidents had occurred in the past and been forgotten—or remembered but discounted—like the structural amnesia the Arenos had encountered. Energy companies had understated the value of these caverns and their contents and had been undertaxed, it was discovered. The problem was not that the state government was too big, too intrusive, too controlling; it seemed to me that the state government had barely been present at all.

Beyond this, there were different expectations of business and government. Companies made money and were beholden to stockholders; it was understandable if they tried to “cover their ass,” people told me. But the government was paid to protect people, so one could expect much more of them. Still, victims felt surprisingly hurt by Texas Brine, belying hope of a more personal touch. “After the sinkhole, company officials didn’t come around to ask how we were doing. And after they reimbursed us, they gave us a month to get out,” one aggrieved refugee told me, “When an ill eighty-three-year-old man asked Texas Brine for more time to get out they said, ‘Okay, an extra week.’” Texas Brine didn’t care. They were all about money. Mike himself expressed mixed feelings toward Texas Brine. He offered a bag of Satsuma mandarins to the Texas Brine manager at the beginning of one community meeting, quipping, “These don’t have razors in them.” Later he told me, “I laughed but the manager didn’t.” Victims were mad that Texas Brine “didn’t have a heart,” but not contemptuous. On the other hand, state officials were seen as tepid followers of corrupt higher-ups, whose envied new SUVs were seen as “paid for by my taxes.”

Overall, just how well did Louisiana state officials do in protecting its citizens? An eye-opening 2003 report from the inspector general of the EPA offered an answer. Charged with evaluating implementation of federal policies by each state within the nation’s six regions, the report ranked Louisiana lowest of all in Region 6. Companies had not been required to submit reports. Louisiana’s database on hazardous waste facilities was filled with errors. The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (a title missing the word “protection”) did not know if many companies were or were not “in compliance.” Delays allowed sixteen facilities to discharge material into Louisiana waters without permits. The agency had failed to inspect many plants. Even when it found companies out of compliance, it had neglected to levy penalties or, if they were levied, to collect them. The inspector general concluded that he was “unable to fully assure the public that Louisiana was operating programs in a way that effectively protects human health and the environment.”

Why such low marks? Three reasons, the inspector general concluded: natural disasters, low funds, and “a culture in which the state agency is expected to protect industry.” As for lack of resources, funding for environmental protection had been cut in 2012 from a previous 3.5 percent of total yearly state funds to 2.2 percent. An alert auditor had also discovered that the state had accidentally “given back” about $13 million to oil and gas companies that it should have retained in taxes. As for the pro-industry “culture,” permitting was indeed relatively easy. According to the state’s own website, 89,787 permits to deposit waste or do anything that affected the environment were submitted between 1967 and July 2015. Of these, only sixty—or .07 percent—were denied.

Some state reports also reflected odd science. Comparing rates of pollution in different areas, detection levels were sometimes set high in the one and low in the other. In a 2005 study of the Calcasieu Estuary, Louisiana state scientists inexplicably concluded that it would be dangerous for children aged six to seventeen to swim in estuary waters, but not dangerous for “children six and under.” Such reports were also nearly unreadable. One typical report read: “Analyses reported as non-detects were analyzed using method detection limits that were higher than the comparison values used as screening tools.”

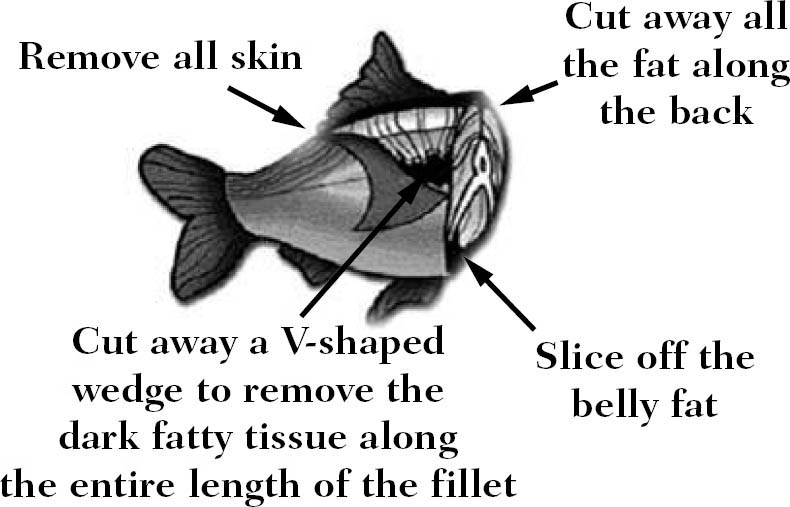

Sometimes the state simply lowered standards of protection. In an astonishing example of this, the Louisiana State Department of Health and Human Science offered advice to officials in other state agencies on what to tell the public about which fish are safe to eat. Issued in February 2012, and still online as of May 5, 2016, the report was written by one set of state officials for another. After a chilling description of a “cancer slope factor,” the report continues, in a matter-of-fact tone, to advise the recreational fisherman on how to prepare a contaminated fish to eat: “Trimming the fat and skin on finfish, and removing the hepatopancreas from crabs, will reduce the amount of contaminants in the fish and shellfish,” the document reads. Baking, broiling, and grilling are good, it said, because “the fat drains away from the fish and shellfish.” Discard “juices which contain the fat . . . to further reduce exposure,” it says. “Some contamination, like mercury and other heavy metals, however, are pervasive in the edible fish tissue,” the report continues, in scientific deadpan prose, “and remain in the fish and shellfish even after cooking.”

The report was shocking but it also made a certain grim sense. If the companies won’t pay to clean up the waters they pollute, and if the state won’t make them, and if poverty is ever with us—some people need to fish for their dinner—well then, trim, grill, and eat mercury-soaked fish. At least the authors of the protocol were honest in what was a terrible answer to the Great Paradox. “You got a problem? Get used to it.”

Protocol for Issuing Public Health Advisories for Chemical Contaminants in Recreationally Caught Fish and Shellfish

Mike Schaff had heard nothing of this advice, but when I describe it, he shakes his head. “There it is again, more bad government. Why raise salaries? Take Steve Schultz, who heads our Department of Natural Resources. When he first went to work for me and other Louisiana taxpayers, he started at $30,000, probably bought himself a mobile home or efficiency apartment his family could fit in. Then he got raises and moved to some fancy subdivision. Say we increase the budget for environmental protection. His salary rises from $150,000 to $190,000. The more money we give him, the more reason he has to be a yes man to Jindal and oil. To me, a public servant who doesn’t make very much is more likely to be dedicated to what he’s doing.”

Mike’s idea of dedication was modeled on the church. On another visit, Mike had driven me in his red truck to the Catholic grade school he’d attended across the street from the Catholic church where he had been confirmed and next to a graveyard where his parents and maternal grandparents lay buried. He recalled the nuns instructing him to clap the blackboard erasers on the sidewalk (God would reward him if he did). But he remarked in passing, “The nuns were great teachers and lived very modestly. I think all public servants ought to be like those nuns.” They wouldn’t need much tax money. But he realized that the incentives to enter public service would be almost nil, making it hard to attract the best people, and on yet another visit, he confessed, “I could never live like they do.”

Thinking over the Bayou Corne disaster, I was still puzzled. Mike embraced a free-market world because he wanted to preserve community. But did a total free-market world and local community go together? And in essence, wasn’t Louisiana already like a society based on a near pure free market? Governor Jindal advocated the free market and small government—Mike had voted for him on those very grounds. He had cut public services, lowered funds for environmental protection, and installed pro-industry “protectors.” The state hadn’t functioned to protect the residents of Bayou Corne at all and, in the minds of some, had even absorbed the main blame for the sinkhole, just as Lee had absorbed the blame for PPG’s pollution of Bayou d’Inde.

Having explored all the places the Great Paradox had taken me—from the 4,000-feet-deep storage vaults in the Napoleonville salt dome to the advice of state officials to recreational fishermen on how to prepare mercury-laced fish—I thought I was looking at an open-and-shut case for good government. But my new friend saw in this advice on how to prepare a contaminated fish an open-and-shut case for less government.

I had criticisms of the federal government myself—over-surveillance, the declaration of war in Iraq, letting off Wall Street speculators behind the 2008 crash, for example. But my criticisms were based on a faith in the idea of good government.

Mike lands his boat at his dock and we return to his dining room table. He has told me that we don’t need Social Security or Medicare. “Take Social Security. If you and I hadn’t had to pay into it,” he told me, “we could have invested that money ourselves—even given the 2008 downturn—you and I would be millionaires by now.”

We didn’t need the Federal Department of Education, he thought (that could go to each state) or the Department of the Interior (we could privatize most public land). But hadn’t Texas Brine just treated the public waters of Bayou Corne as if the company privately owned them? Did Mike want more of that? I was feeling stuck way over on my side of the empathy wall. So I turned my question around.

“What has the federal government done for you that you feel grateful for?”

He pauses.

“Hurricane relief.” He pauses again.

“The I-10 . . .” (a federally funded freeway). Another long pause.

“Okay, unemployment insurance.” He had once been briefly on it.

I suggest the Food and Drug Administration inspectors who check the safety of our food.

“Yeah, that too.”

“What about the post office that delivered the parts of that Zenith 701 you assembled and flew over Bayou Corne Sinkhole to take a video you put on YouTube?”

“That came through FedEx.”

The military in which he enlisted as an ROTC officer?

“Yeah, okay.” Another pause.

And so it went. We don’t need this, we don’t need that. Other interviews went the same way, with the same long pauses.

How about the 44 percent of the state budget that comes from Washington, D.C.? Mike searches his mind. “Most of that goes for Medicaid. And at least half of the recipients, maybe more, aren’t looking for work.”

“Do you know any?” I ask.

“Oh sure,” he answers. “And I don’t blame them. Most people I know use available government programs, since they paid for part of them. If the programs are there, why not use them?” On another visit Mike recounted a near accident and rescue; he was taking his new bride and her two daughters on a boat ride when a powerful storm came up, his motor quit, and the boat rocked heavily. “First the girls screamed with delight. Then they got quiet. We almost capsized. Luckily the Coast Guard saw us and towed us to shore. I was glad to see him,” Mike said, adding, “He did check if we had safety vests which I guess is okay.”

What image of the government was at play? Was it a nosy big brother (the Coast Guard had checked for safety vests)? Was it a remote-controlling big brother (a federal instead of state Department of Education)? A bad parent playing favorites (affirmative action)? An insistent beggar at the door (taxes)? It was all of these, but something else too. Just as Berkeley hippies of the 1960s felt proud to be “above consumerism,” to demonstrate their higher ideals of love and world harmony—even though they often depended on the parental money they were “above”—so too Mike Schaff and other Tea Party advocates seemed to be saying, “I’m above the government and all its services” to show the world their higher ideals, even though they used a host of them. For everything else it is, the government also functions as a curious status-marking machine. The less you depend on it, the higher your status. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen long ago observed, our distance from necessity tends to confer honor.

I count all the reasons Mike disdained government. It displaced community. It took away individual freedom. It didn’t protect the citizenry. Its officials didn’t live like nuns. And the federal government was a more powerful, distant, untrustworthy version of the state government. Beyond that, Mike was surrounded by a local culture of endurance and adaptation; if fish have mercury, cut around the dark meat and eat the white. It was this culture of adaptation that Mike himself would later challenge, as we shall see.

But something else animated Mike’s dislike for the government, something I was to discover wherever I went. Sometimes talk of it was angry, front and central; sometimes it was quietly alluded to. But over their heads, the federal government was taking money from the workers and giving it to the idle. It was taking from people of good character and giving to people of bad character. No mention was made of social class and enormous care was given to speak delicately and indirectly of blacks, although fear-tinged talk of Muslims was blunt. If the flashpoint between these groups had a location, it might be in the local welfare offices that gave federal money to beneficiaries—Louisiana Head Start, Louisiana Family Independence Temporary Assistance Program, Medicaid, the national School Lunch and Breakfast Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Liberals were telling Americans to “feel sorry” for recipients, but those were coastal urban liberals trying to impose their feeling rules on older Southern and Midwestern Christian whites. And they seemed to be on the other side. So I wondered: did some of the malaise I was seeing derive from a class conflict, appearing where one least expected it (in the realm of government) and between groups (the middle/blue-collar class and the poor) that liberals weren’t focusing on? Was this a major source of resentment fueling the fire of the right? And in that fight, did the entire federal government seem to them on the wrong—betraying—side? Maybe this was the main reason Mike was later to tell me, in reference to the 2016 presidential election and only half jokingly, that he could never bring himself to vote for the menshevik (Hillary Clinton) or the bolshevik (Bernie Sanders).

As I leave, Mike hands me the jar of peaches that had been on the table when I arrived. I drive back up Crawfish Street, past tilting yards, onto the potentially sinking only exit route, and wonder what news of Bayou Corne, federal regulations, handouts, and much else he received from church or from his favorite television channel—Fox News.