Did the Great Flood take place as depicted in the Bible?

Can Noah’s ark be found?

The tale of the biblical Flood and of Noah’s ark is familiar to most readers in the Western world and to many others as well. As the story in the Hebrew Bible goes, God instructed Noah to build an ark, since the world was about to be flooded as punishment for the sins and evil of humankind. We read as follows:

Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence. And God saw that the earth was corrupt; for all flesh had corrupted its ways upon the earth. And God said to Noah: “I have determined to make an end of all flesh, for the earth is filled with violence because of them; now I am going to destroy them along with the earth.” (Genesis 6:11-13)

Noah was a righteous man, however, so God decided to save him and his family, along with two of every kind of living creature. Therefore, God commanded Noah to build the ark, and instructed him on its dimensions and the number of floors there should be, and who could come on board:

Make yourself an ark of cypress wood; make rooms in the ark, and cover it inside and out with pitch. This is how you are to make it: the length of the ark three hundred cubits, its width fifty cubits, and its height thirty cubits. Make a roof for the ark, and finish it to a cubit above; and put the door of the ark in its side; make it with lower, second, and third decks. For my part, I am going to bring a flood of waters on the earth, to destroy from under heaven all flesh in which is the breath of life; everything that is on the earth shall die. But I will establish my covenant with you; and you shall come into the ark, you, your sons, your wife, and your sons’ wives with you. And of every living thing, of all flesh, you shall bring two of every kind into the ark, to keep them alive with you; they shall be male and female. (Genesis 6:14-19)

We are told that the Flood lasted for 40 days and 40 nights (6:17), and that floodwaters covered the earth for 150 days. All living things drowned, with the exception of Noah and the people and animals that were with him in the ark (Genesis 7:11-24).

The biblical story next tells us that Noah’s ark “came to rest on the mountains of Ararat” (Genesis 8:4). We must note that the Bible does not say the ark came to rest specifically on top of Mount Ararat, as many people assume, but rather on the “mountains of Ararat.” These mountains are most likely in the region of ancient Urartu, near modern-day Armenia. Mount Ararat in Turkey—where people have been searching for Noah’s ark on and off for the past century—was apparently given that name only within the past few centuries at most, according to scholars. Because of this, some enthusiasts and explorers have suggested and investigated other possible locations for the ark, including Iran, as we will see.

The biblical account continues on, explaining that once the ark rested on the mountaintop, Noah released various birds in an effort to determine if the Flood waters had receded and if dry land had appeared. And so we are told that Noah sent out a raven, which flew around until the waters dried up, and that he also sent forth a dove three times, waiting one week in between each try. The third time the dove did not come back, which Noah interpreted to mean that dry land had begun to appear. So he opened up the ark and he, his family, and all of the animals disembarked (Genesis 8:1-20).

The animals go two by two into Noah’s ark in this 13th-century depiction. But was there one pair or seven pairs of each animal? (Illustration Credits 2.1)

Then he offered up a sacrifice of thanksgiving for being saved, and the story ends on a happy note, at least for Noah and his family:

Then Noah built an altar to the Lord, and took of every clean animal and of every clean bird, and offered burnt offerings on the altar.… God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth.” (Genesis 8:20–9:1)

LONG AGO, BIBLICAL SCHOLARS demonstrated that there are at least two versions of the creation story within the Book of Genesis. Similarly, scholars have long noted that the biblical account of Noah and his ark actually consists of two different stories that have been woven together. As a result, details within the Bible’s account contradict themselves, as many scholars have pointed out, including Richard Elliott Friedman, professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California at San Diego and author of Who Wrote the Bible?

For instance, we are told that the Flood lasted for 40 days (Genesis 7:17) but also that the floodwaters covered the earth for 150 days (7:24). Which was it—40 or 150 days? Or did it rain for 40 days but then take an additional 110 days for dry land to appear? And how many animals was Noah told to take into the ark? One pair of each kind of animal (6:19)? Or seven pairs of each kind of clean animal and one pair of each kind of unclean animal (7:2)? And did he release a raven which “went to and fro until the waters were dried up from the earth” (8:7), or did he release a dove three different times before “it did not return to him ever again” (8:8-12)? Or was it both?

There are additional examples as well, as other scholars have demonstrated in great detail, which show that whoever put the Hebrew Bible together in the form we know it today was using at least two versions of the Flood story. However, we are left with numerous questions. When was each of these versions originally created? And by whom? These are difficult questions to answer, but we already possess some of the data that will eventually allow us to answer them.

IN 1872, George Smith was working in the basement of the British Museum. By day he was a bank official; by night he was an assistant in the Assyriology section of the museum, sorting and translating clay tablets excavated from the ancient site of Nineveh. One evening he began translating the contents of a tablet and found, much to his astonishment, that it told the story of a great Flood and a man who had survived it by building a boat and bringing his family and assorted animals on board. Rather than landing on Mount Ararat, however, this man’s boat came to rest on a mountain called Nisir.

Quickly sorting through the rest of the tablet fragments in the basement, Smith found more pieces and was able to determine that it was, indeed, a story about the Flood, but that it didn’t feature a man named Noah. Moreover, he was missing a big piece of the original tablet, right in the middle of the story. When he announced his discovery, the British media went wild, and the London Daily Telegraph offered him a thousand British pounds (a large sum in those days) if he would go to Iraq in search of the missing fragment. This appeared to be a nearly impossible challenge, but Smith accepted.

He proceeded to Nineveh, finally arriving after an arduous and dangerous journey. Rather than beginning fresh excavations of this ancient site, he began digging instead through the “back dirt” piles left by the previous British excavators. These piles of earth accumulate during every excavation, because the dirt that the archaeologists dig through and remove must be put somewhere (in fact, enormous back dirt piles can be seen today at the site of Troy in Turkey and at the site of Megiddo in Israel, to mention two famous instances). Frequently, these back dirt piles, especially those from earlier excavations, contain hundreds of objects that have been missed by the early archaeologists and their huge teams of local workers.

Sure enough, within just a few days of beginning his search at Nineveh, George Smith found more than 300 fragments of clay tablets on the excavation’s back dirt pile, including the missing piece of the story. He was able to read the entire account now, confirming his earlier announcement that this Mesopotamian story of the Flood was amazingly similar to the story told in the Bible. And yet there were a number of differences, which left Smith and his fellow scholars with the task of explaining the relationship between these two stories. One possibility, embraced by many people, was that this Mesopotamian tablet confirmed the biblical account and was proof that the great Flood had actually taken place.

What many of these people did not realize (and many still do not) is that there are several even earlier versions of the same story, all from ancient Mesopotamia. The oldest known version of the Flood account comes from the Sumerians, a civilization that flourished in what is now modern Iraq during the late fourth and third millennia B.C. In that story, which dates to some time during the third millennium B.C., the hero is named Ziusudra. A later copy of this original Sumerian Flood story was found on a clay tablet in the city of Nippur in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and dates to about 1740 B.C. It includes the following lines:

Clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia describe a great flood, but do not mention anyone named Noah. (Illustration Credits 2.1)

All the destructive winds (and) gales were present,

The storm swept over the capitals.

After the storm had swept the country for seven days and seven nights …

And the destructive wind had rocked the huge boat in the high water,

The Sun came out, illuminating the earth and the sky.

Ziusudra made an opening in the huge boat,

And the Sun with its rays entered the huge boat.

The king Ziusudra

Prostrated himself before the sun god;

The king slaughtered a large number of bulls and sheep.

Around the beginning of the second millennium B.C., a new version of the story emerged, with the name of the hero changed to Atrahasis. Then around 1800 B.C. or maybe a bit later, someone took a group of separate, earlier stories and wove them together to form one great work, the Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh was a king who ruled in the Sumerian city of Uruk sometime during the years 2700 and 2500 B.C., but he was not present in the original versions—including the original Sumerian tale—of the Flood. Thus, the earlier stories were rewritten where necessary in order to introduce Gilgamesh into the epic narrative. For example, the epic inserts Gilgamesh into the Flood account by having the survivor of the Flood tell him the story. This time, however, the hero is not Ziusudra or Atrahasis but a man named Utnapishtim, who says to Gilgamesh: “I will reveal to you a mystery, I will tell you a secret of the gods.”

The Epic of Gilgamesh became a favorite tale, and was told and retold, copied and recopied over the centuries. A fragment of the epic was even found at Megiddo in Israel, probably dating from the late second millennium B.C. A copy was also found at Nineveh in the library of the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, who ruled in the seventh century B.C.—and that was the tablet George Smith read in the basement of the British Museum on that fateful day in 1872.

Each of these Flood stories, whether from the Sumerians, Akkadians, or Babylonians, is extremely similar to the one told in the Hebrew Bible about Noah and his ark. They all explain that God (or the gods) decided to flood the world and drown its inhabitants. However, one man was saved, along with his family and whatever animals he was able to take with him on board. He—whether named Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Utnapishtim, or Noah—sailed for a period of time until the ark eventually came to rest on top of a mountain. The hero then sent out several birds, which came back one after the other, until the waters receded and the bird in question did not return. The humans disembarked, released the animals, made sacrifices in gratitude, and then went forth and multiplied.

For example, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh that the god Ea instructed him to build a ship and outfit it as follows:

These are the measurements of the barque as you shall build her: let her beam equal her length. Let her deck be roofed like the vault that covers the abyss; then take up into the boat the seed of all living creatures.… On the fifth day I laid the keel and the ribs, then I made fast the planking. The ground-space was one acre, each side of the deck measured one hundred and twenty cubits, making a square. I built six decks below, seven in all, I divided them into nine sections with bulkheads between.… I loaded into her all that I had of gold and of living things, my family, my kin, the beast of the field both wild and tame, and all the craftsmen.

As we can see, this is much like the story of Noah and the ark. The length of time the Flood lasted and what happened after it ended are also very similar to the biblical account; although we are told in these earlier Mesopotamian stories that the rain lasted for only six days and six nights, even in that short span of time “all mankind had returned to clay.” What is perhaps even more interesting is that the Epic of Gilgamesh tells us that the gods themselves were frightened by the Flood: “The gods are terrified by the deluge, they flee and mount to the heaven of Anu; the gods cowered like dogs in an enclosure.” This is certainly an unusual way to describe one’s gods, but it is consistent with the Mesopotamian worldview in which the gods and their society were viewed as similar to humans (including a fear of thunder and lightning, in this case), except that they were endowed with eternal life.

Yet even if the similarities between the various stories are quite unmistakable, it is sometimes the differences that are the most interesting, particularly when the biblical version has had a new moral or ethical twist added to it. For example, the reason God sent the great Flood in the Hebrew Bible is well known: It was because humankind was corrupt and violent and needed to be punished. However, the Old Babylonian version, dating to the early second millennium B.C., gives a very different reason for the sending of the Flood:

You know the city Shurrupak, it stands on the banks of the Euphrates? That city grew old and the gods that were in it were old. There was Anu, lord of the firmament, their father, and warrior Enlil their counselor, Ninurta the helper, and Ennugi watcher over canals; and with them also was Ea. In those days the world teemed, the people multiplied, the world bellowed like a wild bull, and the great god was aroused by the clamor. Enlil heard the clamor and he said to the gods in council, “The uproar of mankind is intolerable and sleep is no longer possible by reason of the babble.” So the gods agreed to exterminate mankind.

This account is not unique; in all the various versions of the Flood story that were floating around Mesopotamia a good 900 years before the Hebrew Bible was written, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, the gods agreed to exterminate the human race not because mankind was corrupt and evil but because there were too many people, they were being too noisy, and the gods could not get to sleep. In the Bible the Flood is sent for a moral reason, but in the original Mesopotamian versions, morals and spiritual concerns are nowhere to be found and the reasons the Flood is sent are comparatively mundane.

This is an interesting twist that we find over and over again when comparing a biblical story to the versions that were circulating in the ancient Near East hundreds of years earlier: Although there are obvious similarities, the most significant changes are the moralistic or ethical endings or twists that were added to the original story to illustrate a point the biblical writers wanted to make. Thus, according to the biblical account, Noah was saved because he was a righteous man. But no particular reason is given in the earlier Mesopotamian versions for why Ziusudra, Atrahasis, or Utnapishtim were spared:

Ea … warned me in a dream. He whispered their words to my house of reeds, “Reed-house, reed-house! Wall, O wall, hearken reed-house, wall reflect; O man of Shurrupak, son of Ubara-Tutu; tear down your house and build a boat, abandon possessions and look for life, despise worldly goods and save your soul alive. Tear down your house, I say, and build a boat.”

The similarities continue when the ark finally comes to rest on a mountaintop. Just as Noah eventually landed on the mountains of Ararat and disembarked with all of his family and animals, so Utnapishtim landed on Mount Nisir and similarly disembarked. The biblical story tells us that Noah released a raven and then a dove three times to determine if the waters had receded and if dry land had begun to appear. In the earlier Babylonian and Sumerian stories, the survivor of the Flood also released birds, but in these versions, it was a dove, followed by a swallow, and then a raven—and it was the raven that did not come back and presumably found dry land.

The Hebrew Bible then says, “Noah built an altar to the Lord, and took of every clean animal and of every clean bird, and offered burnt offerings on the altar” (Genesis 8:20). The Epic of Gilgamesh describes a similar scene, but in a way that no modern society would ever consider doing. “I brought a sacrifice on the mountain top,” says Utnapishtim. “Seven and seven cult jars I arranged. Beneath them I strewed reeds, cedarwood and myrtle. The gods smelled the odor, the gods smelled the sweet odor. The gods like flies gathered around the sacrifices.”

What do we make of all this? If each of these stories simply stated that a Flood took place and one man and his family survived, we might conclude that a worldwide Flood really did occur and that the biblical account can be confirmed by these earlier Mesopotamian stories. And, indeed, many people today do take these stories at face value and reach exactly that conclusion—in part because almost all civilizations, from the Greeks to Native Americans, have some sort of Flood legend.

What makes these stories much more than a simple confirmation of the biblical account, however, is that not only is the plot essentially the same, but many of the minute details are similar as well, and yet centuries—and sometimes millennia—separate one version from another. Thus, scholars tend to favor the suggestion that these stories are an example of a transmitted narrative. In fact, most scholars today think the story of Noah’s ark is one of the best examples of such a narrative. Originating in ancient Mesopotamia and making its way from the Sumerians to the Babylonians and then to the Canaanites and the Israelites, the tale of Noah and his ark has not only spanned generations, it has also spanned civilizations, with only a few details changed before finally ending up in the Hebrew Bible.

IN 1929, SIR LEONARD WOOLLEY, a British archaeologist, was excavating at the site of Tell el Muqayyar, in what is now modern Iraq. His workmen had dug through a level of river silt between eight and twelve feet thick that had been laid down by a flood that occurred in antiquity. The levels immediately above and below the river silt contained pottery, indicating that people had been living at the site—which Woolley identified as ancient Ur—both before and after the flood hit. As the story goes, upon viewing this deposit, Woolley’s wife casually remarked, “Well, of course, it’s the Flood.” Woolley’s subsequent announcement that he had found evidence for the biblical Flood made the front page of newspapers around the world that year.

Later, Woolley retracted his statement, having concluded that, while what he had found was indeed the remains of a flood, it was only a local flood and not one of biblical proportions. Since Woolley’s discovery, evidence for other floods has been uncovered at a number of additional sites in Mesopotamia, including Nineveh and Kish, but none of them seem to indicate that the flood was anything more than a local catastrophe, with each occurring at a different time than the others.

In 1998, a much more relevant discovery was announced by William Ryan and Walter Pitman, two geologists at Columbia University, who published evidence for a great flood emanating from the Black Sea, located north of Turkey. They presented data that indicated the sea had broken through its barriers and flooded a large area in Turkey (and perhaps even farther south) around 7,500 years ago, in approximately 5500 B.C.

Whether Ryan and Pitman are correct in their interpretation of this data has been hotly debated in the years since their book appeared. In 1999, Bob Ballard, the discoverer of the Titanic, turned up evidence of an ancient shoreline deep below the surface of the Black Sea—one complete with shells from freshwater and saltwater mollusk species whose radiocarbon dates support Ryan and Pitman’s theory that a freshwater lake was inundated by the Black Sea some 7,500 years ago. Whether this flood would have been large enough to come to the attention of the Sumerians and other ancient peoples remains a matter of debate. But, at the moment, the evidence seems fairly convincing that, at the very least, a large area around the Black Sea would have been affected by the sudden rise in water.

Unfortunately, beyond these two instances, there is no other good archaeological or geological evidence for the existence of the biblical Flood or for Noah and his ark, despite numerous claims to the contrary by amateur sleuths and scholars each year. These claims run the gamut from theories involving meteors from outer space to the simultaneous eruption of geysers across the world to the sudden collapse of a heavy cloud cover. None has been accepted by the scientific community as an adequate explanation.

The closest we might come to some sort of additional archaeological or geological evidence for a biblical Flood is to suggest that all the Flood stories found around the world are essentially a folk memory of the end of the Ice Age, when much of the ice covering various parts of the continents melted and water levels around the world rose. But even this is sheer speculation, because it is by no means clear that this occurrence would have given rise to worldwide stories of such a Flood. Similarly, the Flandrian Transgression, which caused a sudden rise in sea level sometime between 5000 and 4000 B.C. and flooded the southernmost portions of Mesopotamia, probably occurred too slowly to be remembered as the Flood.

Sir Leonard Woolley excavated the site of Tell el Muqayyar in Iraq, which he identified as Ur of the Chaldees. (Illustration Credits 2.3)

MOST EXPEDITIONS GOING in search of Noah’s ark focus primarily on the area of Mount Ararat (Agri Dagi) in northeastern Turkey, even though it is not at all certain that this location is where they should be looking. Ancient writers such as Josephus, the Jewish general turned Roman historian, were also unclear as to where to search and variously suggested that the ark came to rest in what is now southern Armenia, Iraq, central Asia Minor, and even Saudi Arabia. Although many of the modern expeditions have claimed success, none has succeeded in producing tangible evidence or even reasonable hypotheses sufficient to persuade the scholarly and scientific establishments.

Early Expeditions—William Stiebing, emeritus professor of history at the University of New Orleans, has been keeping track of the numerous expeditions that have gone in search of Noah’s ark. Stiebing has published a list of these expeditions, which he has updated in various publications over the past 20 years. Stiebing’s list includes perhaps the earliest official expedition, led by the British explorer Sir James Bryce in 1876. According to Stiebing, Bryce claimed to have found “a large piece of hand-tooled wood at the 13,000-foot level of Mt. Ararat.”

One interesting expedition concerned a group of Russian soldiers who supposedly found the ark after it was spotted from the air in 1915, but claimed the Russian Revolution of 1917 occurred before they could return home and report their findings. Another infamous set of claims came from Fernand Navarra, who in 1955 said that he had found a five-foot-long piece of wood in a crevasse on Mount Ararat. The wood was initially dated to 3000 B.C. by a Spanish laboratory, but was subsequently redated to between A.D. 260 and A.D. 790, plus or minus 90 years, via carbon-14 dating methods. Thus, the wood—and other pieces found in the same location on Mount Ararat in 1969—was deemed much too recent to be from Noah’s ark. Stiebing suggests that Navarra’s findings may be from “the remains of some wooden structure (perhaps a chapel, a replica of the Ark, or a hut for climbers) built near the snow line … during the Middle Ages.”

Since then, various expeditions and claims have been made every couple of years—including two led by ex-astronaut James Irwin (of Apollo 15) in the 1980s—but none of the claims have been verified and none of the expeditions have panned out.

Wyatt’s Ark—Perhaps the most infamous set of claims and series of expeditions were those made by Ron Wyatt, a nurse anesthetist from Nashville with an interest in archaeology, who first traveled to Turkey in 1977 to examine a “boat shaped object” that had been reported on in Life magazine. By 1979, Wyatt claimed that he could see evenly spaced indentations all the way around the object, which “looked like decaying rib timbers,” as well as “horizontal deck support timbers” also present at consistent intervals. Eventually, by June 1991, Wyatt claimed that he could see “an object that when observed … bore the shape of a very large ‘rivet’ head, with a washer around it.”

Two months later, in August 1991, Wyatt and three of his ark-seeking companions were taken hostage by Kurdish separatist rebels and held for three weeks before being released. This put a stop to their expeditions. To this day, Wyatt’s claims are embraced by enthusiastic admirers but few, if any, scholars.

Cornuke’s Ark—In July 2006, Bob Cornuke, a former police investigator and SWAT team member turned “biblical investigator, international explorer, and best-selling author,” led the most recent expedition in search of Noah’s ark. Cornuke originally served as a security advisor and provided protection for ex-astronaut James Irwin and his team as they searched for the remains of Noah’s ark in Eastern Turkey during the 1980s—in the same region where Ron Wyatt and his colleagues were later kidnapped and terrorized by Kurdish separatist rebels. After Irwin’s death, Cornuke founded the BASE (Bible Archaeology Search and Exploration) Institute and began his own series of explorations.

Media reports announced that Cornuke’s 2006 expedition team had discovered boat-shaped rocks at an altitude of 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) on Mount Suleiman in Iran’s Elburz Mountains. The same media reports also stated that photographs taken by expedition members showed a rock outcrop shaped like the prow of a boat emerging from a ridge. Cornuke stated that the rocks looked “uncannily like wood.… We have had [cut] thin sections of the rock made, and we can see [wood] cell structures.”

Cornuke’s claims failed to convince most experts, though. Kevin Pickering, a geologist at University College London who specializes in sedimentary rocks, said, “The photos appear to show iron-stained sedimentary rocks, probably thin beds of silicified sandstones and shales, which were most likely laid down in a marine environment a long time ago.” Moreover, Robert Spicer, a geologist at England’s Open University who specializes in the study of petrification, said: “What needs to be documented in this case are preserved, human-made joints, such as … mortice and tenon, or even just pegged boards. I see none of this in the pictures. It’s all very unconvincing.”

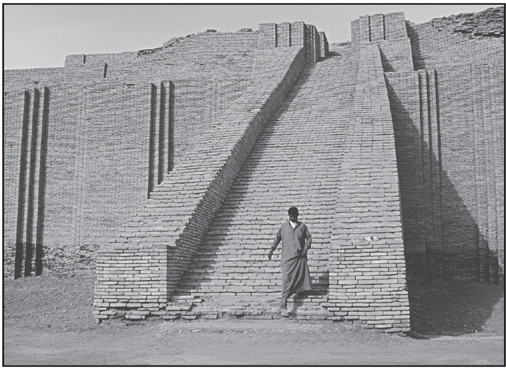

Mesopotamian ziggurats, such as this 4,000-year-old one at Ur, were religious structures that may have given rise to the story of the Tower of Babel. (Illustration Credits 2.4)

IT IS DIFFICULT, if not impossible, to put the biblical story of the Flood and Noah’s ark into historical context, since these events took place well before the beginning of recorded history, which is considered to be circa 3000 B.C., when writing was invented in both Mesopotamia and Egypt.

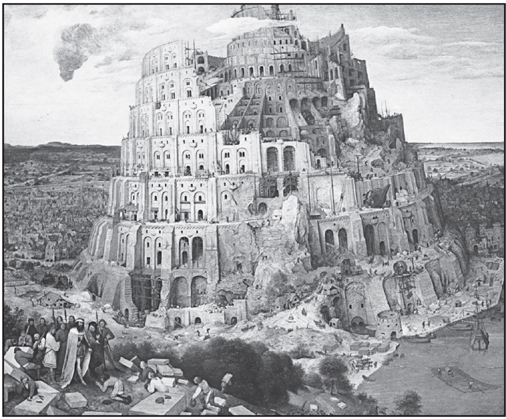

We should take this opportunity to mention the story of the Tower of Babel here, even if it seems to be a bit of a tangent, because it appears immediately after the story of Noah’s ark in the Book of Genesis (11:1-9). More important, the tower’s description fits the archaeological remains of the second millennium B.C. religious structures that we call ziggurats, which were built in Babylon, Uruk, Ur, and elsewhere in Mesopotamia. Thus, the Babel tale may serve as one point where a portion of Genesis could be reflected in the actual archaeological record.

The original story of the Tower of Babel may well have been invented in order to explain why there were so many different languages in the world as well as to highlight the importance of Babylon. In the biblical version, the tale has been tweaked and is generally considered by scholars to be a judgment against humankind because of its hubris and sin. The biblical account says:

Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” The Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built. And the Lord said, “Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.” So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth. (Genesis 11:1-9)

Archaeologists and ancient historians generally place the “plain in the land of Shinar” in the region of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in Mesopotamia. There, the city of Babylon rose, made famous especially by Hammurabi (circa 1792–1750 B.C.), who issued his famous Law Code (which we shall discuss in chapter 4). The city lasted for more than a thousand years, rising and falling in prominence; it is in this city that Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C.

One of the most visible structures, and enduring monuments, in the city of Babylon was the pyramid-shaped ziggurat. The ziggurat was built in several stages with increasingly smaller sections placed one on top of the other, reaching so high that it appeared to have “its top in the heavens,” just as the Bible describes. Such ziggurats, which were built in many major Mesopotamian cities during the second millennium B.C., served a religious function. (As an aside, it has been suggested that the ziggurat at Babylon was also the real location for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—since draping plants and other vegetation off each of the stages of the ziggurat would have resulted in a veritable hanging garden.)

Linking the Tower of Babel to the ziggurat that stood in Babylon during the second millennium B.C. may seem to be a stretch in trying to place the biblical story of the Flood and of Noah’s ark into historical context—and indeed it is. However, the point is simply that it is possible to explain some mysteries that appear in the biblical account, insofar as they may be historical memories of things Babylonian or Sumerian that filtered down through the centuries to the Israelites and eventually made it into the Bible.

IT IS CLEAR FROM the textual evidence that there are a number of major similarities and minor differences between the Flood story in the Hebrew Bible and those found in the earlier civilizations of Mesopotamia, which all predate the writing of the Bible by at least eight or nine centuries. So where does that leave us?

The vast majority of scholars agree that the Flood tales told by the earlier Sumerian and Babylonian civilizations—especially the version found in the Epic of Gilgamesh—probably represent the historical kernel at the base of the biblical story of the Flood and Noah’s ark. The question then becomes whether there is any truth to the stories of Ziusudra, Atrahasis, and Utnapishtim—the survivors of the earlier floods. Unfortunately, it is impossible to answer this question.

The story of the Tower of Babel, depicted here in Pieter Bruegel’s famous 1563 painting, may have been written to explain why there are so many languages in the world. (Illustration Credits 2.5)

Of course, there are many, many Flood stories found in other civilizations across the world, from Alaska to Australia, but they are all from much later periods. Even the earlier stories from other civilizations, such as the Greek myth of Deucalian and the Flood, are most likely also borrowed from the Near East during periods of cultural contact that took place long after the initial stories were written, such as the Orientalizing period in Greece during the early first millennium B.C. Around that time several stories, including the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh and the Hittite Myth of Kumarbi, made their way West, eventually influencing Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Hesiod’s Theogony.

In terms of archaeological evidence, Noah’s ark has not yet been found, despite recent claims to the contrary. There are indications, however, that a number of floods varying in size and intensity occurred in Mesopotamia and elsewhere in the ancient world, including in the Black Sea region.

What, then, does all of this say about the existence of Noah and his ark? Did they ever exist? Can we ever find their remains? I can only answer the last of these questions. I would argue that whether or not a great Flood took place, it is unlikely we will ever find the remains of Noah’s ark … and if we do, it will be by accident, when we are looking for something else. Such a discovery will only happen if the ark has been fortuitously petrified or otherwise accidentally preserved—and the odds are stacked against such a chance circumstance having occurred.

The truth of the matter is that any such searches for Noah’s ark are unlikely ever to be successful. Even if the ark did exist, it would be tremendously old by now and its wooden parts would have been long ago reduced to dust, leaving few traces behind. The most we could hope for would be discovering something like the Sutton Hoo ship in England from the seventh century A.D.; the disintegrated wood and corroded nails from this vessel left a perfect imprint on the damp soil. Only if the ark had come to rest in the sands of Egypt, which contain perfectly preserved pharaonic boats by the Pyramids, or at the bottom of an ocean or a sea where there is little oxygen and organic material is perfectly preserved—such as in the Black Sea, where Bob Ballard’s expeditions have found ships sunk up to their gunwales and perfectly preserved in anoxygenic mud—would we even be able to hope that Noah’s ark, or portions of it, have been preserved.

The most unlikely place to find Noah’s ark is probably on top of a mountain, such as Mount Ararat in Turkey, where most expeditions go looking for it, or even on the mountains of Ararat, where the Bible says the ark landed. It is a very long shot to hope that the ark has been preserved in glacier ice like the woolly mammoths in Siberia or like “Ötzi the Iceman,” the 5,000-year-old man (dating to 3200 B.C.) found frozen, reasonably intact, and quite well preserved on the Italian-Austrian border in the Alps during the mid 1990s.

In the end, we are still left with a series of major questions: Why are so many people looking for Noah’s ark, while not a single person is looking for Utnapishtim’s ark or Ziusudra’s ark or Atrahasis’s ark? Why are we so interested in the biblical story and yet almost nobody has heard of the earlier Babylonian and Sumerian versions, which are almost identical? Why is no one searching for Mount Nisir, but numerous expeditions search on Mount Ararat, or the mountains of Ararat, looking for Noah’s ark nearly every year? Are these mountains in fact one and the same or are they different? If we find one, are we likely to find the other? Or are we doomed to watch one optimistic expedition after another fail? These are questions for which I, and everyone else for that matter, have yet to find answers.